Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Depression, Family Support, and Body Mass Index in Mexican Adolescents

Cargado por

Berenice RomeroTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Depression, Family Support, and Body Mass Index in Mexican Adolescents

Cargado por

Berenice RomeroCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Revista Interamericana de Psicologia/Interamerican Journal of Psychology - 2013, Vol. 47, Num. 1, pp.

139-146

139

Depression, Family Support, and Body Mass Index in Mexican Adolescents H£

Kelsey Caetano-Anolles Ö

Margarita Teran-Garcia' C

Marcela Raffaelli O

CO

University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA

Brenda Alvarado Sanchez

Miguel René Mellado Garrido

Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, Cd. Valles, S.L.P., México

Abstract

The relationship between depressive symptomatology and elevated Body Mass Index (BMI), and

between family support and low BMI is controversial. There are unanswered questions about the

relationship between these three variables We tested the hypothesis that positive family support

mediates the association between depression and body weight responsible for overweight and obesity

in Mexican youth. We explored if family support correlated with depression and if depressive symp-

tomatology correlated with obesity. Our results indicate that the relationship between depression and

family support was significant (r = -0.44, p = 0.004). A significant relationship between depression

and BMI was found only in women. When family support is included into the equation, the effect

of depression on BMI disappeared. This observation indicates family support is a partial mediator

between depression and obesity in adolescents. Our results are important and prompt an extended

analysis of likely causative links between psychosocial parameters and health descriptors.

Keywords: BMI, Depression, Family Support, Mexico, Youth

Depresión, apoyo familiar, y Indice de Masa Corporal en adolescentes mexicanos

Resumen

La estrecha correlación entre sintomatologia depresiva y elevado índice de Masa Corporal (IMC),

y entre apoyo familiar y bajo IMC demostrada por algunos estudios es debatible. Nuestra hipótesis

es que, durante la juventud, los aspectos positivos del apoyo familiar actúan como mediadores en la

asociación entre depresión y peso corporal, siendo responsables del elevado IMC. Exploramos si el

apoyo familiar correlaciona con depresión y si sintomatologia depresiva se correlaciona con obesi-

dad. La relación entre depresión y apoyo familiar fue significativa (r = -0.44, p = 0.004). La relación

entre depresión e IMC fue significante exclusivamente en mujeres. Cuando el apoyo familiar fue

incluido en la ecuación, el efecto de depresión sobre IMC se redujo a niveles no significativos. Esto

indica que el apoyo familiar es un mediador parcial entre depresión y obesidad juvenil. Exponemos

la necesidad de realizar análisis adicionales para discernir vinculos entre parámetros psicosociales

e indicadores de salud.

Palabras clave: IMC, depresión, apoyo familiar, México, juventud

Excess bodyweight is a condition that affects health tions (Haslam & James, 2005). As the obesity epidemic

and life expectancy and is spreading in human popula- continues to surge around the world, researchers at-

tempt to identify the primary factors associated with

obesity. The correlational relationship between obesity

' Correspondence about this article should be addressed to Depart- in youth and the onset of serious health problems in

ment of Food Sciences and Human Nutrition; Division of Nutritional adulthood, such as heart disease and diabetes, has

Sciences; Affiliate to the Department of Psychology; University of been demonstrated (Baker, Olsen, & Sorensen, 2007).

Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; 437 Bevier Hall, MC-182; 905 S However, connections between obesity in youth and

Goodwin Avenue; Urbana, Illinois 61801 USA. Email: teranmd@

important psychological and environmental correlates,

illinois.edu and Department of Human & Community Development;

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; 2003 Doris Kelley such as depression and family support, have not been

Christopher Hall, MC-081; 904 West Nevada Street; Urbana, IL adequately established.

61801 USA. Email:; mraffael@illinois.edu Depression is a psychological condition that lowers

R. Interam. Psicol. 47(1), 2013

KELSEY CAETANO-ANOLLES, MARGARITA TERAN-GARCIA, MARCELA RAFFAELLI,

BRENDA ALVARADO SANCHEZ & MELLADO GARRIDO MIGUEL RENÉ

140 mood and causes sadness, anxiety, and loss of interest adds to an already existing pool of cross-sectional and

W in human activities (Ainsworth, 2000). It is a normal longitudinal studies supporting a positive correlation

O human condition but is also the result of medical con- between depression and BMI (Hasler et a l , 2005;

O ditions, drug treatments, and psychiatric syndromes. Revah-Levy et al., 2011).

Family support entails tangible entities that are pro- Next, it is important to analyze the relationship

vided by family members to an individual, including between family support and depression. In sharp con-

emotional and instrumental support, care-giving effort, trast to the conflicting findings regarding associations

decision-making, and evenfinancialassistance. Several between depression and BMI, a negative correlation

studies have shown that a correlational association ex- between family support and depressive symptoms

ists between depressive symptomatology and elevated among adolescents has been consistently demonstrated.

body mass index (BMI), depression and family support, Weinman et al. (2003) examined 110 adolescents at-

and between family support and BMI (Gerald et al., tending a U.S. family planning clinic and determined

1994). BMI is calculated using the weight and height that there was indeed a significant correlation between

of human individuals and is used as a heuristic proxy family support and depressive symptoms. These initial

by the World Health Organization to determine weight results were supported by a study of adolescents in

trends and obesity levels (WHO Expert Consultation, Florida (Christman et al., 2009). Participants aged 17-19

1995). The very few studies that have examined these were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory, a

parameters provide conflicting results, some support- set of 21-items assessing levels of depression, and the

ing and other negating correlational relationships. Modified Perceived Social Support (PSS) from Fam-

Additional research should be conducted, particularly ily (Fa) and Friends (Fr) Scale, a 50-item assessment

focusing on a Mexican population. questionnaire. Results showed that high levels of family

Here we focus on Mexican adolescents. Our ratio- support were significantly correlated with decreased

nale for selecting this group was primarily the fact depression at a level that was unparalleled by even high

that although obesity rates are skyrocketing around levels of friend support.

the world, Mexico has been especially affected by the There is limited published literature examining the

epidemic. Recent reports have found that about one relationship between family support and BMI. Wicz-

out of every three Mexicans over 16 are overweight, inski et al. (2009) found suggestive evidence for this

and, at the same time, they have nutritional deficiencies association: in their sample of almost 3,000 German

due to poor dietary choices (Celis de la Rosa, 2003). participants, social support seemed to buffer what

In terms of family support, the 2000 National Youth they refer to as "obesity-related impairments." Other

Survey found that not only do most young adults spend studies indicate an indirect association between the

most of their time with their family but they also look two variables. A correlation between family support

to family members for support and would consider and physical activity (PA) among adolescents has

their relationship to be close (Encuesta Nacional de been consistently demonstrated (Kohl & Hobbs, 1998;

Juventud, 2000). However, adolescents consider inter- Sallis, Prochaska, & Taylor, 2000). Similarly, growth

family communication to be poor, especially with their curve analyses from a longitudinal investigation of

fathers, and feel that their parents do not understand 421 adolescent girls in South Carolina ascertained that

them or listen to their feelings (Encuesta Nacional family support for physical activity (measured using

de Juventud, 2000; Villasenor Farias, 2003). This five items that assessed encouragement, participation,

simultaneous dependence and conflict could increase transportation and watching of PA by family members)

depression levels and BMI and alter the effect of fam- was independently related to physical activity levels

ily support as the mediator of the relationship between (Dowda et al., 2007). These findings are significant

depression and obesity. since it has been shown that physical activity and

Before taking steps to tackle the obesity epidemic in obesity are negatively correlated (Riebe et al, 2009).

any region of the world, it is important to understand Although the relationship between depression and

the association between depression and BMI. Luppino BMI has been established, important questions involv-

et al. (2010) conducted a systematic review and meta- ing families and Wellness remain unanswered. Here we

analysis of longitudinal studies, which examined this examined whether family support can act as a protec-

association - the first meta-analysis of its kind. In their tive factor in this association by sampling a population

analysis of 15 studies, they found bidirectional asso- of adolescents from a university campus in Mexico.

ciations between these two factors: obese individuals

were 55 percent more likely to become depressed, and

those who were depressed were 58 percent more likely

to become obese (Luppino et al., 2010). This report

R. Interam. Psicol. 47(1), 2013

DEPRESSION, FAMILY SUPPORT, AND BODY MASS INDEX IN MEXICAN ADOLESCENTS

Research Hypotheses indigenous component in the makeup of the state's

population and possibly of the student body of the

Based on literature and what is known about de- university. Only 15% of the population has college

pression, one would expect BMI to be associated with education (similar to the national average of 16.5%). O

depression among adolescents. For example, a cultural We consider our sample to represent this 15% transect

ideal of thinness for women has been proposed to cause of the state's population and note that the number of 5

registered students seeking undergraduate degrees at CO

body dissatisfaction, eating disorders and depression at

higher rates in women than in men (McCarthy, 1990). the university in 2010-2011 was 24,776,51.1% of whom

The onset of eating disorders and depression in these were males (Informe UASLP, 2010-2011).

cases has been reported to be higher before puberty Out of the approximately 10 applicants who applied

and generally associated with Western societies and for admission every day during a period of 5 months

urban settings. The correlated epidemiology of depres- (February to June, 2010), 2 were recruited as research

sion and eating disorders is also linked to body image participants each day. Consent forms approved by the

perception in men (Olivardia et al., 2004). Culture Institutional Review Board (IRB) both in Mexico and

therefore impacts the body and mind interface. Eating in the United States were signed. Individuals were

disorders are expected to affect overweight and obesity randomly assigned to complete one of two versions

incidence. For example, the prevalence of binge eating of a questionnaire. Form "A" asked questions regard-

disorder (2-5%) increases up to 30% in individuals ing medical history and related topics, and Form "B"

seeking weight control treatment and can be treated focused on psychosocial aspects. Only data collected

by cognitive behavior therapy and psychotherapy (de from Form "B" was utilized in this study. Question-

Zwaan, 2001). Finally, the social fabric of family and naires were administered in a classroom setting with

society are also expected to affect overweight/obesity a coordinator who was available to answer any ques-

incidence and correlated psychological conditions, tions. Participants were given as much time as they

very much as family support affects physical activ- needed to respond to the survey. The analytic sample

ity among adolescents. Since it is unknown whether consisted of 102 applicants aged 16 to 25 (mean age:

18.17 years) (Table 1).

family support plays any role in the links of BMI and

depressive symptomatology, here we aim to test three

Measures

specific hypotheses:

Demographic Measures. Questions regarding sex,

(1) Depressive symptoms will be positively corre-

age, indigenous ancestry, and other demographic in-

lated with obesity.

formation were asked on the first pages of the survey.

(2) Family support will be negatively correlated with Participants were considered as having indigenous

depression. ancestry if they answered "yes" to at least one of the

(3) Family support will mediate the association be- following questions: "Usted se considera indígena?"

tween depression and obesity. (Do you consider yourself indigenous?), "Su padre o

madre se considera indígena?" (Does your father or

mother consider themselves indigenous?), "Su abuelo

Method o abuela paterna se considera indígena?" (Does your

paternal grandfather or grandmother consider them-

Participants and procedures selves indigenous?), "Su abuelo o abuela materna se

Information was obtained from a larger sample of considera indigena?" (Does your maternal grandfather

applicants at the Unidad Académica Multidisciplinaria or grandmother consider themselves indigenous?).

Zona Huasteca of the University of San Luis Potosi Depression. Depressive symptomatology was mea-

in Mexico. La Universidad Autónoma de San Luis sured using the 10-item version of the Center for Epide-

Potosi is the largest public university serving the state miologie Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10; Kohout

of San Luis Potosí, one of the 31 states of Mexico. The et al., 1993). The CESD-10 is a valid and reliable self-

university was the first to gain constitutional autonomy administered questionnaire assessing the frequency

and receives students from all 58 municipalities of the of depressive symptoms experienced during the past

state. Of the state's population in 2011, 48.7% were week on a scale from 1 = "Rarely or none of the time

males, 30.4% were less than 15 years of age, and 63.8% (less than 1 day)", 2 = "Some or a little of the time (1-2

resided in populations with more than 2,500 inhabit- days)", 3 = "Occasionally or a moderate amount of time

ants (INEGI, 2011). The median age of the state was (3-4 days)", 4 = "All of the time (5-7 days)." Positive

25 years (below the national average of 26). A total of items are reverse coded and respondent answers are

10.7% of the population speaks indigenous languages converted into point values (0 to 3). Points from the 10

(above the national average of 6.7%), indicating a high items were averaged; possible scores range from 0-3.

R. Interam. Psicol. 47(1), 2013

KELSEY CAETANO-ANOLLES, MARGARITA TERAN-GARCIA, MARCELA RAFFAELLI,

BRENDA ALVARADO SANCHEZ & MELLADO GARRIDO MIGUEL RENÉ

142 Body mass index (BMI)/ BMI is calculated by but marginal significance was noted due to the small

CO dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters sample size. Preliminary analyses were conducted by

O squared, and can be used to classify individuals as running simple correlations. As prior literature re-

O underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese. The ported gender differences in the associations between

cut-off points set by the World Health Organization the study variables, we conducted analyses by gender.

are as follows: Underweight = <18.5, normal weight = Mediation analyses were conducted following the

18.5-24.99, overweight: 25-29.99, obese = >30 kg/m2 procedures laid out by Baron and Kenny (1986). They

(WHO Expert Consultation, 1995). BMI was used as maintained that the following criteria must be met in

a continuous variable in our analyses, but cutoffs were order to establish mediation: first, the independent vari-

used for descriptive purposes in the tables. able must affect the mediator; second, the independent

Family Support. Family support was measured variable must affect the dependent variable; third, the

using an abbreviated version of the family support mediator must affect the dependent variable (Baron &

subscale from the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Kenny, 1986). These analyses were conducted control-

Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & ling for age and indigenous ancestry.

Farley, 1988). The measure has been translated into

Spanish (European) and validated (Mantuliz & Castilo, Results

2002). To measure family support in the present study,

two of the four family-related items were administered Sample

{Puedo hablar con mi familia sobre mis problemas [I The analytic sample consisted of 102 Mexican ado-

can talk with myfamily about my problems]. Mifamilia lescents with ages ranging from 16 to 25,53% of whom

esta dispuesta a ayudarme a tomar decisiones [My were female and 38% of whom were of indigenous

family is willing to help me make decisions]). Each ancestry (Table 1). The majority (64%) of the sample

item was rated on a 7-point scale (from very strongly was of normal weight; 8% was underweight, 16% over-

disagree to very strongly agree) and an overall score weight and 12% obese. The proportion of overweight

created by averaging. and obese males was slightly larger than that of females.

About 12% of respondents showed elevated symptoms

Plan of Analysis of depression, mostly females.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM

SPSS Statistics 19. Significance levels were set at 0.05,

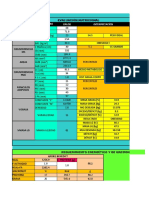

Table 1.

Characteristics of study sample (N = 102)

Measure Male Female Total

Sample Size 48 54 102

Age (years)* 18 ± 2, (16-25) 18 ±1, (16-25) 18.17 ± 1.49, (16-25)

25.13 ±5.03, 23.33 ± 4.89, 24.18 ± 5.02,

BMI (kg/m2)*

(15.88-40.40) (16.28-38.80) (15.88-40.40)

Underweight 2 (4.17%) 6(11.11%) 8 (7.84%)

Normal Weight 26 (54.17%) 33 (61.11%) 59 (57.64%)

Overweight 10 (20.83%) 6(11.11%) 16 (15.69%)

Obese 7 (14.58%) 5 (9.26%) 12(11.76%)

Indigenous (yes) 17 (35.42%) 19 (35.19%) 36 (38.24%)

Depression* 3.63 ±2.49, (0-11) 6.65 ± 4.26, (0-18) 5.19 ±3.81, (0-18)

Depressed

1 (2.08%) 11 (20.37%) 12(11.76%)

(CES-D score >10)

*Mean ± SD, (Minimum - Maximum)

R. Interam. PsicoL 47(1), 2013

DEPRESSION, FAMILY SUPPORT AND BODY MASS INDEX IN MEXICAN ADOLESCENTS

Preliminary Tests of Study Hypotheses sex played an important role in the interplay of vari- 143

Analyses conducted to test the first hypothesis that ables. Indeed, in analyses conducted separately for

depressive symptoms will be positively correlated with men and women, the association between depression

BMI, revealed no significant association (see Table 2). and BMI was marginally significant among women but O

However, there were significant correlations between not men (Table 3).

gender and both depression and BMI, indicating that 5

CO

Table 2

Bivariate Correlations

Variable (scale alpha)

1. Sex

2. Age -.01

3. Indigenous ancestry .00 .17*

4. BMI -.18* .15 -.05

5. Depression .40** .10 .22* .01

6. Family support -.03 .04 -.08 -.07 -.28*

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (1-tailed).

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (1-tailed).

Similar results were found when testing the second gender it was significant among women but not men

hypothesis that family support is negatively correlated (Table 3). On the basis of these results we confined and

with depression. The correlation was significant in the test our hypotheses exclusively among females.

overall sample (Table 2) but when examined within

Table 3

Bivariate Correlations by Gender

Variable (scale alpha) 1 2 3 4 5

1. Age - .05 .03 .19 . .09

2. Indigenous ancestry .27* - -.06 .20 -.09

3. BMI .27* -.049 - -.18 .00

4. Depression .06 .31* .25* - -.18

5. Family support .00 -.05 -.]6 -.40** -

Note. Values for males displayed above the diagonal, and for females below.

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (1-tailed).

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (I-tailed).

An interesting finding was a correlation between (1986), controlling for age and indigenous ancestry. Re-

indigenous ancestry and depression (Table 2) that was sults of these analyses are displayed in Figure 1. We first

also confined to women (Table 3). This finding that tested whether the independent variable, depression,

links ethnicity to depression is weakened by the low affects the dependent variable, BMI. Analyses showed

sample size of the indigenous population, hampering that this relation was marginally significant. Next, we

sub-group analysis. tested whether the independent variable, depression,

affects the mediator, family support. Analyses showed

Tests of Mediation that this relationship was significant. Finally, we tested

We hypothesized that family support mediates the whether the mediator affects the dependent variable in

association between depression and obesity. Mediation a third equation that included depression and family

analyses were conducted on the sub-sample of women support as predictors of BMI. Although the coefficient

following the procedures laid out by Baron and Kenny between depressive symptoms and BMI dropped to

R. Interam. Psicol. 47(1), 2013

KELSEY CAETANO-ANOLLES, MARGARITA TERAN-GARCIA, MARCELA RAFFAELLI,

BRENDA ALVARADO SANCHEZ & MELLADO GARRIDO MIGUEL RENÉ

144 non-signíficance, the association between family sup- was no significant association between depressive

CO port and BMI was not significant. Subsequent Sobel symptoms and BML These results are not consistent

O test calculations indicated that the indirect effect was with findings reported by Hasler et al. (2005) but match

D not significant. observations from longitudinal analyses (Wardle et al.,

O

2006). Moreover, when conducting analyses separately

tr Figure 1. for men and women, we found that the correlation be-

<

Direct relations among depression. Body Mass Index tween depression and BMI was marginally significant

(BMI), andfamily support and the model of the medi- for women and not men (Table 3), indicating that gender

ating effect of family support on the relation between is important in the depression-BMI relationship.

depression and BMI among women (n = 54). As expected, family support was negatively cor-

related with depression, although this association was

Family Support

significant only for women. This confirms previous

analyses of comparable adolescent populations in the

United States (Weinman et al, 2003; Christman et al.,

-396" (p = .006) -.18 (ns) 2009). A recent study in Latino/a youth examined how

patterns of social support can lead to healthy outcomes,

but did not find a gender difference (de Guzman, Jung

& Do, 2012). Future studies could evaluate what is the

Depression BMI role of immediate family in social support networks to

248V.186(ns) foster positive practices of physical health behaviors,

including nutrition habits and practices.

Note. Controlled for age and indigenous ancestry. There is no single explanation for the novel finding

*p<.10 that family support partially mediated the effect of

**/?<.01 depression on BMI among Mexican adolescent females.

The notion that family support improves mental health,

Discussion disrupting a link between depression and obesity is not

startling. However, why this partial mediation occurs

Our study focuses on the relationship between three exclusively among women is unknown. One possible

variables - depression, elevated BMI, and family sup- explanation is that adolescent women stay at home

port. While a careful longitudinal analysis established longer before moving out, keeping them closer to their

an association between depressive symptoms during families and the support which improves psychological

childhood and obesity in adulthood (Hasler et al., wellbeing. Indeed, a vast number of Mexican families

2005), the important correlation has been contested are maintained united in Mexico and women marry

in subsequent studies or deemed much more complex. young (average 18.8 years of age) and generally expand

In contrast, a correlation between family support and families in number of members and not in number of

depressive symptoms (Weinman et al., 2003) seems family units. The "Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica

well established (Christman et al., 2009). This lays a Demográfica" identified that 10 million families in-

foundation for our hypothesis that family support me- eluded all children ('nuclear' families with an average

diates the association between depression and obesity. of 4.8 family members) and 2.6 million families in-

Our rationale for selecting Mexican indigenous ado- cluded children and other family members ('extended'

lescents for our study was the lack of existing research families with an average of 6 members), with nuclear

done on this population and the skyrocketing rates of families representing 73.3% of the population of the

obesity in Mexico, which has been especially affected country (INEGI, 1999). These families represent the

by the epidemic. Interesting cultural issues arise, such vast majority of the population, 88.1 million. Families

as the fact that although adolescents look to family for show overall equilibrium in male-female composition

support, they consider inter-family communication to and have a makeup of 24.6% and 23.8% of children

be poor and feel that their parents are not receptive 0-9 years of age and 10-19 years of age, respectively.

(Encuesta Nacional de Juventud, 2000; Villasenor There is however a bias towards increases in family

Farias, 2003). This perception of conflicting family makeup of females of 15 years of age and above. For

dependence relationships could increase depression example, within the age range of 15-19 years, families

levels and BMI and mediate the association between are composed of 5.4% males and 5.7% females, and

depression and obesity. It is important to keep this the trends become more and more pronounced with

cultural context in mind when reviewing results. ranges of increasing age. The trend is more marked

Our study indicates that in the overall sample there in extended than nuclear families and suggests that

R. Interam. PsicoL 47(1), 2013

DEPRESSION, FAMILY SUPPORT, AND BODY MASS INDEX IN MEXICAN ADOLESCENTS

females tend to remain in families longer than men, critical for immigrant populations that are increasing 145

even if they are ready for work. More importantly, only at fast pace, but especially for the Mexican immigrant

4 out of 100 children remain in the original family unit population of the United States. The Mexican popula-

after 30 years of age and families have a considerable tion of the United States has explosively expanded in ñ

number of members 20-59 years of age (44.9%). In recent years, mostly by illegal immigration, and is c

fact, extended families are enriched in both young and affecting the population makeup of many states. The

elderly. More importantly, presence of females 15 years Hispanic population is concentrated in the Southwest

o

Crt

and above increases significantly in members of the of the United States and in Illinois, Florida, and North

family that are non-children, indicating an important Carolina, but is notably increasing in the Southeast.

role of sisters-in law and sisters in the Mexican fam- United States health systems like many others will need

ily. This indicates that families are fluid but in many to adjust to the challenge of addressing the obesity epi-

cases maintain unity through elders and women. While demic and the specific impact that cultural and ethnic

further investigation should be conducted to determine factors have on health and family Wellness.

what lifestyles of Mexican women could possibly be

responsible for the flndings of family mediation we References

report here, census data from Mexico clearly suggests

a differential family impact on women materializing Ainsworth, P. (2000). Understanding depression. Jackson, Miss.:

University Press of Mississippi.

already at numerical level. Although there are not many Baker, J. L., Olsen, L. W., & Sorensen, T. I. (2007). Childhood

studies on gender differences in the developmental body-mass index and the risk of coronary heart disease in

trajectory of Mexican adolescents, a recent study of adulthood. TheNew England Journal of Medicine, 357,2329-

the general population found that they find jobs, leave 2337. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056%2FNEJMoa072515

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator

home, marry, start a family, and simply mature at an variable distinction in social psychological research: Con-

earlier age than what is the norm in other cultures ceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal

(Fierro Arias, & Moreno Hernández, 2007). However, of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182. doi:

examining a women-only analysis gives further insight 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Celis de la Rosa, A. (2003). La salud de adolescentes en cifras

into this gender difference. [Adolescent health in figures]. Salud Publica de Mexico.

The limitations of this study include population- 45, 153- 66. 9. http://bvs.insp.mx/rsp/articulos/articulo_

related and methodological aspects. Primarily, our e2.php?id=001567

sample size was relatively small, consisting of only 102 Christman, S. T., Ahn, S., & Nicolas, G. (2009). Perceived fam-

ily and peer social support and depression in young adults.

participants. Only 38% of our sample was indigenous. Poster presented at the 85th Annual ACPA, College Student

This hampered our ability to perform subset analyses. Educators International Convention, Washington, DC.

The correlation between indigenous ancestry and Cohen, S., Kamarck, T, & Mermelstein, R.. (1983). A global mea-

depression in Mexican women represents an interest- sure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behav-

ior, 24(4), 385-396. doi:I0.2307/2136404

ing and potentially significant association that should De Zwaan, M. (2001). Binge eating disorder and obesity. Inter-

be explored in an expanded population. Also, the national Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Dis-

measure of family support was derived from only two orders, 25 (supplement 1), S51-S55. doi: http://dx.doi.

family-related items from the MSPSS. Ideally, more org/10.1155%2F2012%2F407103

Dowda, M., Dishman, R. K., Pfeiffer, K. A., & Pate, R. R. (2007).

items should be used to develop a composite score. Family support for physical activity in girls from 8th to 12th

Finally, the cross-sectional design of this study limits grade in South Carolina. Preventive Medicine, 44, 153-159.

our ability to determine the pathways of association doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.ypmed.2006.10.001

between factors. To overcome these limitations we are Encuesta Nacional de Juventud (ENJ) 2000. (2002). Jóvenes Mexi-

canos del Siglo XXI. México: IMJ-CIEJ, SEP. Available at:

planning to extend these studies to a larger population http://www.conadic.salud.gob.mx/pie/enc_juventud_2002.

of adolescents sampled from the same Mexican state. html

The high percentage of indigenous ancestry, in this Fierro Arias, D., & Moreno Hernández, A. (2007). Emerging

subpopulation of San Luis Potosi, is a unique feature adulthood in Mexican and Spanish youth: Theories and

realities. Journal of Adolescent Research. 22, 476-503.

that could be used to test how culture and genetics doi:10.1177/0743558407305774

affects the complex dynamics between depression, Gerald, L., Anderson, A., Johnson, G., Hoff, C , & Trimm, R.

families and obesity. (1994). Social class, social support and obesity risk in chil-

Given that obesity rates are increasing at alarming dren. Child: Care, Health, and Development, 20(3), 145-63.

doi: 10.1111/j.l365-2214.1994.tb00377.x

rates not only in Mexico but around the world, our de Guzman, M.R.T, Jung, E., Do, K.A. (2012). Perceived social

findings reinforce the need to carefully re-examine the support networks and prosocial outcomes among Latino

association between body weight and social, psycho- youth. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 46(3), 413-424.

logical and cultural factors that impinge on the mental Haslam, D. W., & James, W. R (2005). Obesity. Lancet, 366, 1197-

209. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-l

and physical wellbeing of human populations. This is

R. Interam. Psicol. 47(1), 2013

Revista Interamericana de Psicología/Interamerican Journal of Psychology - 2013, Vol. 47, Num. 1, pp. 139-146

146 Hasler G., Pine D.S., Kleinbaum D.G., Gamma A., Luckenbaugh Weinman, M. L., Buzi, R., Smith, P. B., & Mumford, D. M. (2003).

D., Ajdacic V., Eich D., Rössler W. & Angst J. (2005). De- Associations of family support, resiliency, and depression

pressive symptoms during childhood and adult obesity: The symptoms among indigent teens attending a family planning

2 Zurich cohort study. Molecular Psychiatry, 10(9), 842-850. clinic. Psychological Reports, 93, 719-731. doi: http://dx.doi.

doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001671 org/10.2466/PR0.93.7.719-731

o INEGI. (1999). Las familias Mexicanas [Mexican families]. Se- WHO Expert Committee. (1995). Physical status: The use and

gunda Edición. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía interpretation of anthropometry. WHO Technical Report Se-

(INEGI), Mexico. Pp.156, http://www.inegi.org.mx/siste- ries, World Health Organization, Geneva.

mas/productos/ Wiczinski, E., Döring, A., John, J., von Lengerke, T. (2009).

INEGI. (2011). Perspectiva estadística [Statistics perspective]. San Obesity and health-related quality of life: Does social

Luis Potosí. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía support moderate existing associations? British Journal

(INEGI), Mexico. Pp.93, http://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/ of Health Psychology, 14(4), 717-734. doi: http://dx.doi.

productos/ org/10.1348/135910708X401867

Informe UASLP. (2010-2011). Indicadores institucionales [Insti- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988).

tutional indicators]. Universidad Nacional de San Luis Po- The multidimensional scale of perceived social support.

tosí. Pp.320. http://www.uaslp.mx/Spanish/Rectoria/rector/ Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30-41. doi:10.1207/

InfoAnual sl5327752jpa5201_2

Kohl, H. W. & Hobbs, K. E. (1998). Development of physical

activity behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediat-

rics, 101, 549-554. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/con-

tent/101/Supplement_2/549.full.html Received 10/25/2012

Kohout, F. J., Berkman, L. F., Evans, D. A., & Cornoni-Hunt- Accepted 05/14/2013

ley, J. (1993). Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression

symptoms index. Journal of Aging and Health, 5, 179-193.

doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202

Luppino, F.S., de Wit, L.M., Bouvy, P.F., Stijnen, T., Cuijpers, P., Kelsey Caetano-Anolles. University of Illinois,

Penninx, B.W., Zitman, F.G. (2010). Overweight, obesity, and Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA

depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of lon-

Margarita Teran-Garcia. University of Illinois,

gitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 67(3), 220-9. doi:

IO.lOOl/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2.

Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA

Mantuliz, M. D. A. & Castillo, C. M. (2002). Validación de una Marcela Raffaeili. University of Illinois, Urbana-

escala de apoyo social percibido en un grupo de adultos may- Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA

ores adscritos a un programa de hipertensión de la region Brenda Alvarado Sanchez. Universidad Autónoma

metropolitana. [Validation of a scale of perceived social sup- de San Luis Potosí, Cd. Valles, S.L.P., México

port in a group of seniors assigned to a hypertension program Miguel René Mellado Garrido. Universidad

of the metropolitan region]. Ciencia y Enfermeria, 8,49-55. Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, Cd. Valles, S.L.P.,

McCarthy, M. (1990). The thin ideal, depression and eating disor-

México

ders in women. Behavioral Research Therapy, 28, 205-215.

doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90003-2

Olivardia, R., Pope Jr., H.G., Borowiecki III, J.J., & Cohane, G.H.

(2004). Biceps and body image: The relationship between

muscularity and self-esteem, depression, and eating disorder

symptoms. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 5, 112-120.

doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.5.2.112

Revah-Levy, A., Speranza, M., Barry, C , Hassler, C , Gasquet,

1., Moro, M. R., & Falissard, B. (2011). Association between

Body Mass Index and depression: the "fat and jolly" hypoth-

esis for adolescents girls. BMC Public Health, 11, 649. doi:

10.1186/1471-2458-11-649.

Riebe, D., Blissmer, B. J., Greaney, M. L., Ewing Garber, C ,

Lees, F. D., & Clark, R G. (2009). The relationship between

obesity, physical activity, and physical function in older

adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 21, 1159-1178. doi:

10.1177/0898264309350076.

Sallis, J.F., Prochaska, J. J., & Taylor, W. C. (2000). A review of

correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents.

Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 32, 963-975.

Villaseñor-Farías, Martha. (2003). Masculinidad, sexualidad,

poder y violencia: análisis de significados en adolescen-

tes. Salud Pública de México, 45(Supl. 1), S44-S57. Avail-

able at: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_

arttext&pid=S0036-36342003000700008&lng=es&tlng=es

Wardle, J., Williamson, S., Johnson, F., & Edwards, C. (2006).

Depression in adolescent obesity: cultural moderators of

the association between obesity and depressive symptoms.

International Journal of Obesity, 30, 634-643. doi:10.1038/

sj.ijo.0803142

R. Interam. Psicol. 47(1), 2013

Copyright of Revista Interamericana de Psicología is the property of Sociedad Interamericana

de Psicologia and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a

listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print,

download, or email articles for individual use.

También podría gustarte

- Terapia Vincular-Familiar: Un nuevo abordaje de las sintomatologías actualesDe EverandTerapia Vincular-Familiar: Un nuevo abordaje de las sintomatologías actualesCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (3)

- Evaluacion NutricionalDocumento3 páginasEvaluacion NutricionalkaterinnAún no hay calificaciones

- Formulas de NutricionDocumento2 páginasFormulas de NutricionJessenia Bohorquez100% (2)

- Guía práctica contra la obesidad infantilDe EverandGuía práctica contra la obesidad infantilCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- PRESCRIPCIÓN DEL EJERCICIO FÍSICO EN PACIENTES CON OBESIDAD-fusionadoDocumento15 páginasPRESCRIPCIÓN DEL EJERCICIO FÍSICO EN PACIENTES CON OBESIDAD-fusionadoHECTOR JESUS PEREZ HERNANDEZAún no hay calificaciones

- Terapia Sistémica en ObesidadDocumento16 páginasTerapia Sistémica en ObesidadCarito ConstanzaAún no hay calificaciones

- Ejercicios de Valoración Del Estado NutricionalDocumento4 páginasEjercicios de Valoración Del Estado NutricionalalexanderAún no hay calificaciones

- Apoyo Familiar y Depresion en Adultos MayoresDocumento20 páginasApoyo Familiar y Depresion en Adultos MayoresLUÍS DAVID RUÍZ MORALESAún no hay calificaciones

- Disfuncion FamiliarDocumento5 páginasDisfuncion FamiliarJessica Ramirez VazquezAún no hay calificaciones

- Repercusiones Psicosociales Del Cancer InfantilDocumento9 páginasRepercusiones Psicosociales Del Cancer Infantilrose_bellatrixAún no hay calificaciones

- Apoyo Social y Carga de La Persona Cuidadora en Una Unidad de Salud Mental InfantilDocumento11 páginasApoyo Social y Carga de La Persona Cuidadora en Una Unidad de Salud Mental InfantilPaula RamírezAún no hay calificaciones

- Funcionamiento Familiar y Calidad de Vida en Mujeres Adolescentes Con TCADocumento9 páginasFuncionamiento Familiar y Calidad de Vida en Mujeres Adolescentes Con TCAAnahit Poghosyan KirakosyanAún no hay calificaciones

- Pobreza y Apoyo SocialDocumento1 páginaPobreza y Apoyo SocialJorge J. Rodríguez RenjifoAún no hay calificaciones

- Libro 2018Documento15 páginasLibro 2018Angü GrandaAún no hay calificaciones

- Fichas ItaloDocumento4 páginasFichas ItaloItalo Sanchez AnguloAún no hay calificaciones

- Normas APADocumento4 páginasNormas APAkatty 03Aún no hay calificaciones

- Mujeres Embarazadas y Postpartoy Relacion Con La DepresionDocumento9 páginasMujeres Embarazadas y Postpartoy Relacion Con La Depresionnathaly moralesAún no hay calificaciones

- Dialnet TallaBajaEnLaInfanciaYLaAdolescencia 8079126Documento7 páginasDialnet TallaBajaEnLaInfanciaYLaAdolescencia 8079126ANDRES ZUÑIGA MEDINAAún no hay calificaciones

- Expresión Emocional, Afecto Negativo, Alexitimia, Depresión y Ansiedad en Mujeres Jóvenes Con TrastoDocumento14 páginasExpresión Emocional, Afecto Negativo, Alexitimia, Depresión y Ansiedad en Mujeres Jóvenes Con TrastoFlor LunaAún no hay calificaciones

- Obesidad y Otros TrastornosDocumento7 páginasObesidad y Otros TrastornosKevin Vargas TorresAún no hay calificaciones

- Factores Familiares Asociados A Los Trastornos AlimentariosDocumento13 páginasFactores Familiares Asociados A Los Trastornos AlimentariosCarol BlancoAún no hay calificaciones

- Asociación Entre Estrés, Afrontamiento, Emociones e Imc en AdolescentesDocumento6 páginasAsociación Entre Estrés, Afrontamiento, Emociones e Imc en AdolescentesLpedraza AntesAún no hay calificaciones

- Funcionamiento Familiar Y Trastornos EN LA Conducta Alimentaria de Los Adolescentes Familia Y AdolescenciaDocumento26 páginasFuncionamiento Familiar Y Trastornos EN LA Conducta Alimentaria de Los Adolescentes Familia Y AdolescenciaOana OrosAún no hay calificaciones

- Una Intervencion Multifamiliar Grupal para El Tratamiento Del Deficit AtencionalDocumento9 páginasUna Intervencion Multifamiliar Grupal para El Tratamiento Del Deficit AtencionalCarlos Infante MozaAún no hay calificaciones

- Disfuncion Familiar PDFDocumento5 páginasDisfuncion Familiar PDFAna RojasAún no hay calificaciones

- Afrontamiento FamiliarDocumento26 páginasAfrontamiento FamiliarAnonimo AnonimoAún no hay calificaciones

- Ensayo - Factores Familiares Asociados A Los Trastornos AlimentariosDocumento9 páginasEnsayo - Factores Familiares Asociados A Los Trastornos AlimentariosMaye Hancco sulloAún no hay calificaciones

- La Disfuncionalidad Familiar Como Factores de Riesgo para ObesidadDocumento8 páginasLa Disfuncionalidad Familiar Como Factores de Riesgo para ObesidadSamuel TavaresAún no hay calificaciones

- Factores Psicosociales y Problemas de Salud Reportados Por AdolescentesDocumento10 páginasFactores Psicosociales y Problemas de Salud Reportados Por AdolescentesAndrews Mauricio RamosAún no hay calificaciones

- Nueva Tesis Faces IIIDocumento16 páginasNueva Tesis Faces IIIRuben EstradaAún no hay calificaciones

- Apoyo Socio-Familiar y Afrontamiento Al Estrés Asociado Al Bienestar Psicológico en Personas Con ObesidadDocumento10 páginasApoyo Socio-Familiar y Afrontamiento Al Estrés Asociado Al Bienestar Psicológico en Personas Con ObesidadAndres VasquezAún no hay calificaciones

- Enviar IntroducciónDocumento27 páginasEnviar IntroducciónLima TesisAún no hay calificaciones

- Articulo de Invetigacion Ciencia Social 2 PDFDocumento12 páginasArticulo de Invetigacion Ciencia Social 2 PDFErika JuliethAún no hay calificaciones

- SdvsdisdsfyubsdDocumento10 páginasSdvsdisdsfyubsdMaria Ortiz SagredoAún no hay calificaciones

- Ansiedad, Depresión y Calidad de Un ObesoDocumento7 páginasAnsiedad, Depresión y Calidad de Un ObesoPaz BNAún no hay calificaciones

- 251-Texto Del Artí - Culo-1172-1-10-20220414Documento20 páginas251-Texto Del Artí - Culo-1172-1-10-20220414ANGELICA EDITH CUETO HERNANDEZAún no hay calificaciones

- DepresiónDocumento6 páginasDepresiónJohana Morales OlaecheaAún no hay calificaciones

- Rms181a PDFDocumento6 páginasRms181a PDFRogelio ArronteAún no hay calificaciones

- Burnout EnegementDocumento24 páginasBurnout EnegementLudvick Torres LopezAún no hay calificaciones

- Referencia para La TesisDocumento8 páginasReferencia para La TesisAngela Mauricio AlcoerAún no hay calificaciones

- Investigacion Sobre AutoconceptoDocumento25 páginasInvestigacion Sobre AutoconceptoJulio Cesar CamachoAún no hay calificaciones

- Artículo Científico - Diálisis y Redes de ApoyoDocumento14 páginasArtículo Científico - Diálisis y Redes de ApoyoLashonda PerryAún no hay calificaciones

- Clase 3 Atención A La Salud Con Enfoque Familiar y Comunitario en El Primer Nivel de AtenciónDocumento60 páginasClase 3 Atención A La Salud Con Enfoque Familiar y Comunitario en El Primer Nivel de AtenciónmarianapAún no hay calificaciones

- Bulimia, Truste UnuDocumento4 páginasBulimia, Truste UnuValeAún no hay calificaciones

- 251-Texto Del Artí - Culo-1171-1-10-20220414Documento20 páginas251-Texto Del Artí - Culo-1171-1-10-20220414Mariafe Villanueva UrdaneguiAún no hay calificaciones

- Diferencias de Genero en Afecto Desajuste EmocionaDocumento9 páginasDiferencias de Genero en Afecto Desajuste EmocionaLaura Andrea LlorensAún no hay calificaciones

- 2da lectura-EvaluacionDelFuncionamientoDeUnaFamiliaConUnAdoles-3091362Documento14 páginas2da lectura-EvaluacionDelFuncionamientoDeUnaFamiliaConUnAdoles-3091362Cristian Camilo GutiérrezAún no hay calificaciones

- EJEMPLO - 2021 - Trastornos de La Conducta Alimentaria, Experiencias Adversas Vitales e Imagen Corporal - Una Revision SistematicaDocumento19 páginasEJEMPLO - 2021 - Trastornos de La Conducta Alimentaria, Experiencias Adversas Vitales e Imagen Corporal - Una Revision SistematicaMargarita Trejo VelascoAún no hay calificaciones

- Funcion Familar y ObesidadDocumento43 páginasFuncion Familar y ObesidadFreddy DíazAún no hay calificaciones

- Plan de MejoraDocumento22 páginasPlan de MejoraMILAGROS CYNTHIA JARAMILLO TENORIO DE GARROTEAún no hay calificaciones

- Ok Tesis Esquema Informe Extensivo de Investigacion Ana Magan 17Documento67 páginasOk Tesis Esquema Informe Extensivo de Investigacion Ana Magan 17Josue EgoavilAún no hay calificaciones

- Anorexia Nerviosa PDFDocumento14 páginasAnorexia Nerviosa PDFHugo SantanderAún no hay calificaciones

- TI Imagen Corporal (Resumen)Documento16 páginasTI Imagen Corporal (Resumen)Liam UrizenAún no hay calificaciones

- Hambre Emocional UnamDocumento9 páginasHambre Emocional UnamJuana FlorenciaAún no hay calificaciones

- Exposicion de La Familia en La Salud y La Salud Mental. 090816pptxDocumento18 páginasExposicion de La Familia en La Salud y La Salud Mental. 090816pptxYazMorenoAún no hay calificaciones

- RetrieveDocumento6 páginasRetrieveelein martinezAún no hay calificaciones

- Eficacia de Las Terapias de ParejaDocumento6 páginasEficacia de Las Terapias de ParejaSILVERIO VISALOT CHUQUIPIONDOAún no hay calificaciones

- Meta-Análisis Embarazo en AdolescentesDocumento11 páginasMeta-Análisis Embarazo en AdolescentesDolor RamonaAún no hay calificaciones

- Ejemplo Ta1Documento9 páginasEjemplo Ta1Carlos Casas linoAún no hay calificaciones

- Tipo de Familia Ansiedad y Depresion PDFDocumento3 páginasTipo de Familia Ansiedad y Depresion PDFAnonymous alzR2b1pqAún no hay calificaciones

- Wu-2015 EsDocumento13 páginasWu-2015 EsJIMENEZ MOLINA MIGUEL ANGELAún no hay calificaciones

- Imagen Corporal, IMC, Afrontamiento, Depresión y Riesgo de TCA en Jóvenes UniversitariosDocumento15 páginasImagen Corporal, IMC, Afrontamiento, Depresión y Riesgo de TCA en Jóvenes UniversitariosMaria Guzman100% (1)

- Desajuste Emocional en Parejas InfértilesDocumento8 páginasDesajuste Emocional en Parejas Infértilesmicaela acostaAún no hay calificaciones

- CV LBRG 2022 BNDocumento1 páginaCV LBRG 2022 BNBerenice RomeroAún no hay calificaciones

- Letreros Psic 2023Documento3 páginasLetreros Psic 2023Berenice RomeroAún no hay calificaciones

- Proceso de ReclutamientoDocumento3 páginasProceso de ReclutamientoBerenice RomeroAún no hay calificaciones

- BISBASDocumento1 páginaBISBASBerenice RomeroAún no hay calificaciones

- Efectos de 7 Dietas Populares en El PesoDocumento11 páginasEfectos de 7 Dietas Populares en El PesoMayztAún no hay calificaciones

- XVI Manual de La IAPO ES 7Documento6 páginasXVI Manual de La IAPO ES 7Ibán CruzAún no hay calificaciones

- Caso para Prescripción Del Ejercicio 20201Documento2 páginasCaso para Prescripción Del Ejercicio 20201michael stiven prieto vegaAún no hay calificaciones

- Serrano 2006. % Grasa Corporal PercentilesDocumento10 páginasSerrano 2006. % Grasa Corporal PercentilesValedaboveAún no hay calificaciones

- Plenaria1 Manejo-De-Instrumentos Evaluacion ILA ASNUPE - PPT ModifDocumento73 páginasPlenaria1 Manejo-De-Instrumentos Evaluacion ILA ASNUPE - PPT ModifAntonio Martinez GarciaAún no hay calificaciones

- Trabajo de Campo EDDocumento5 páginasTrabajo de Campo EDMaria Gracia Hernandez PerezAún no hay calificaciones

- BalanzaDocumento1 páginaBalanzaFuneRales GaMezAún no hay calificaciones

- Cal CuloDocumento7 páginasCal CuloAllanVelezAún no hay calificaciones

- Evaluación S7 - Revisión Del IntentoDocumento2 páginasEvaluación S7 - Revisión Del IntentoEmery Sofía C. D. BustamanteAún no hay calificaciones

- Prevalencia de La Obesidad y El Sobrepeso de Una PoblaciónDocumento12 páginasPrevalencia de La Obesidad y El Sobrepeso de Una PoblaciónAngelica GarciaAún no hay calificaciones

- Mediciones Niños 1Documento39 páginasMediciones Niños 1TereHarrisGuerraAún no hay calificaciones

- Practica 01Documento10 páginasPractica 01Nicole RiveraAún no hay calificaciones

- GPC Manejo Quirurgico Obesidad V CortaDocumento23 páginasGPC Manejo Quirurgico Obesidad V Cortaana mariaAún no hay calificaciones

- Ejercicio Crecimiento PediatricoDocumento2 páginasEjercicio Crecimiento PediatricoAnthony Arteaga CogolloAún no hay calificaciones

- Antropometria Taller BasicoDocumento3 páginasAntropometria Taller Basicoalsapo_53348Aún no hay calificaciones

- Tabla de FrecuenciasDocumento5 páginasTabla de FrecuenciasIvan E.P.MendozaAún no hay calificaciones

- Clase 4 - Diabetes, Obesidad y SM Dr. RaymundoDocumento37 páginasClase 4 - Diabetes, Obesidad y SM Dr. RaymundoFernandoGonzalesAún no hay calificaciones

- Gaby TrabajoDocumento5 páginasGaby TrabajoVictor LugoAún no hay calificaciones

- Ultimo MesocicloDocumento15 páginasUltimo MesocicloOrangel RossiAún no hay calificaciones

- ENutr ZhamiraDocumento16 páginasENutr ZhamiraAnibal LeAún no hay calificaciones

- Acondicionamiento Fisico Fase 4Documento12 páginasAcondicionamiento Fisico Fase 4olga100% (1)

- Rutina EntrenamientoDocumento8 páginasRutina EntrenamientoLuis Vicente ArnaoAún no hay calificaciones

- Guía Técnica de Requerimientos de Energía y NutrientesDocumento5 páginasGuía Técnica de Requerimientos de Energía y NutrientesRogerMontesinosFarfan0% (1)

- Tarea 11 - NutriciónDocumento3 páginasTarea 11 - NutriciónMiguel BisonóAún no hay calificaciones

- Rutina 6 Semanas ValeiraDocumento4 páginasRutina 6 Semanas ValeiraEduardo Villalobos BolañosAún no hay calificaciones

- Plantilla GymDocumento2 páginasPlantilla Gympablo sanchez rodriguezAún no hay calificaciones