Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

2586-Texto Del Artículo-7773-1-10-20151209

Cargado por

marisol romeroTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

2586-Texto Del Artículo-7773-1-10-20151209

Cargado por

marisol romeroCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes

Avelino Corral Esteban

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

Resumen: Mucho ha sido escrito sobre el orden de los afijos

pronominales en Lakota (Siouan, 6,000 hablantes: EEUU y Canadá) en

los últimos 150 años. Las propuestas tienden a seguir dos enfoques

opuestos. Uno de estos enfoques defiende que el orden relativo entre los

marcadores de los argumentos del predicado está relacionado con la

asignación de caso o del papel semántico, de tal forma que las formas

pronominales estáticas, las cuales marcan caso acusativo y representan al

paciente, preceden a las formas activas, las cuales marcan caso nominativo

y representan al agente. El otro enfoque sostiene que el posicionamiento

de los afijos pronominales en esta lengua depende del concepto de

persona, de modo que estos afijos siguen el orden tercera persona +

primera persona + segunda persona. Este artículo tiene como objetivo

arrojar alguna luz sobre la cuestión del orden de los afijos pronominales

en Lakota a través del análisis de ejemplos de verbos estáticos transitivos

Financial support for this research has been provided by the Spanish Ministry of

Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO), FFI2011-29798-C02-01/FILO. I wish to

express my gratitude to seven anonymous language consultants, native speakers of

Lakota, Nakoda and Dakota with whom I have conducted fieldwork since 2010, for

kindly sharing their knowledge of this language with me. I am also very grateful to

John E. Koontz for their valuable comments, which have helped to improve the

quality of this paper considerably. All errors, however, remain my sole responsibility.

Avelino Corral Esteban works as a Professor at Universidad Autónoma de

Madrid. He holds a PhD from UNED, a BA in English Philology from Universidad

Autónoma de Madrid and a BA in German Philology from Universidad Complutense

de Madrid. His main areas of research interest cover the study of the grammar of

Native American languages (e.g. Lakota, Cheyenne, Blackfoot, Crow, and Arapaho),

the interaction between syntax, semantics and pragmatics across languages, and the

comparative analysis of the syntax of Romance, Germanic and Celtic languages.

Correo electrónico: avelino.corral@uam.es.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 5

aportados por dos lenguas estrechamente relacionadas con el Lakota, es

decir el Nakota y el Dakota.

Palabras clave: Lengua Lakota, lengua de marcación en el núcleo,

alineamiento intransitivo escindido, afijo pronominal, orden lineal.

Abstract: Much literature has been written on the ordering of pronominal affixes in

Lakota (Siouan, 6,000 speakers: USA and Canada) in the last 150 years. Proposals

tend to take one of two opposing approaches. One is to argue that the relative ordering

among the argument markers is linked to case or semantic role assignment, with stative

forms, marking accusative case and representing patient participants, preceding active

formas, marking nominative case and representing agent participants. The other

approach is to argue that the positioning of pronominal affixes in this language depends

on the concept of person, so these affixes follow the rule third person + first person +

second person. This paper aims to shed some light on the issue of the ordering of

pronominal affixes in Lakota by analyzing examples1 of transitive stative verbs

provided by two closely related languages to Lakota, namely Nakota and Dakota2

Keywords: Lakota language, head-marking language, split-intransitive alignment,

pronominal affix, linear ordering.

1

Abbreviations used in this paper: 1 – first person, 2 – second person, 3 – third

person; SG – singular, PL – plural; STA – stative series of pronominal affixes, ACT –

active series of pronominal affixes; AGIPS – agent impersonalizer, APD – animate

patient dereferentializer, NP – noun phrase; LOC – locative, INSTR – instrumental; CAUS

– causative verb; STEM – part of verbal stem; IF - Illocutionary Force.

2 The data in this paper come from my native consultants, supplemented with

language materials such as the Dakota Grammar (Boas and Deloria, 1941), the New

Lakota Dictionary (LLC, 2011), a Ph.D. Thesis on Assiniboine Nakota language (West,

2003), or a number of papers on Lakota (De Reuse, 1983; Pustet and Rood, 2008,

among others). Throughout this paper I will use the Lakota Language Consortium

orthography system (LLC, 2011: 747-748). Likewise, I have glossed and translated all

of the examples that occur in the paper, even those taken from the supplementary

sources. Needless to say, all errors remain my sole responsibility.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 6

Introduction

The past three decades have witnessed a continuous debate

about the split-intransitive agreement3 pattern in Lakota4, which has

attempted to find a concluding answer to questions about what

these two series mark and what is the linear order of these

pronominal forms preceding the verb root. This paper offers a

study of Lakota morphosyntax, placing special emphasis on the

ordering of pronominal affixes in transitive constructions. Firstly,

this study provides a summary of previous work concerning the

ordering of Lakota pronominal affixes. Once all the different views

on this issue have been presented, I then present a hypothesis,

based on diachronic claims rather than on synchronic claims, which

states that this ordering appears to be influenced by a person

hierarchy, rather than case or semantic role assignment.

1. Lakota verbs and their affixes

Lakota verbs fall into two main groups, namely stative verbs and

active verbs, which are distinguished mainly by the set of the

personal pronouns they take. Most stative verbs are one-place

predicates and are marked with an Object personal affix (e.g. the

stative series), which is realized as a bound morpheme within the

verb:

3 Lakota follows a stative-active or split-intransitive alignment system, because its

intransitive verbs cross-reference subjects differently. That is, depending on language-

specific semantic or lexical criteria, the subject of an intransitive verb in this language

is sometimes marked as the subject of a transitive verb (it is correferenced with the

‘active’ series) and sometimes as the direct object (it is crossreferenced with the ‘stative’

series).

4 Lakota is a Siouan language with a mildly synthetic / partially agglutinant

morphology. Likewise, it is considered a head-marking language, since the marking of

syntactic relations is realised on the head of the clause.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 7

1st. person singular …-ma-…

2nd. person singular …-ni-…

3rd. person singular …-Ø-…

1st. person dual inclusive …-uŋ(k)5 -…

1st. person exclusive /plural …-uŋ(k)-…-pi

2nd. person plural …-ni--…-pi

3rd. person plural animate6

- collective …-wičha-…

- Distributive …-Ø-…pi

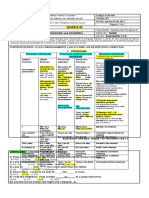

Table 1: The stative series

The other most important group of Lakota verbs is called active

verbs7. They are formally recognized by the fact that they take a

Subject personal affix (i.e. the active series), which is also realized

as a bound morpheme within the verb:

5

In the first person dual and first person plural, a consonant -k- is added when

the next word begins with a vowel.

6

The plural of inanimate arguments is marked by the reduplication of the last

syllable of the verb.

7

This second group of verbs is more heteregenous than the first one and can be

classified into three different classes: Class 1 (e.g. slolyA ‘know’), Class 2 (e.g. yuhá

‘have’) and Class 3 (e.g. yaŋkÁ ‘sit’). Furthermore, a great number of verbs present

irregular paradigms, such as eyÁ ‘say’, yútA ‘eat’ or yÁ ‘go’, etc.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 8

1st. person singular ...-wa/bl/m-…

2nd. person singular …-ya/l/n-…

3rd. person singular …-Ø-…

1st. person dual …-uŋ(k) -…

1st. person plural …-uŋ(k)-…-pi

2nd. person plural …-ya/l/n-…-pi

3rd. person plural animate8 …-a/wičha9-…

- collective …-Ø-…pi

- distributive

Table 2 : The active series

As for their transitivity, most stative verbs are intransitive, while

active verbs can be intransitive, monotransitive or ditransitive.

When the verb is monotransitive, it codes two arguments through

the presence of pronominal affixes, and with the exception of

transitive stative verbs, which are exceptionally rare, these verbs

normally present forms of both the stative and active series

simultaneously.

2. Review of the previous literature on the ordering and

number of affixes in Lakota

Here is a summary of the different proposals that have been

offered regarding the relative order of the two types of cross-

referencing forms in this language10. Furthermore, wherever it is

8

The third person plural inanimate form is never marked overtly in active verbs.

9

The marker wičha can also crossreference third person plural animate collective

subjects in intransitive stative verbs and in some intransitive active verbs: Wičhawášte

‘They (as a group) are good.’ (De Reuse, 1983: 154); Wičhani ‘They (as a group) live.’

(LLC, 2011: 649). The bound form a is used to form a collective plural of verbs of

movement: Áya = ‘They all go there.’ (LLC, 2011: 21).

10 Although word order in Lakota may vary for pragmatic reasons, this language is

believed to have a canonical order subject + object + verb, especially in sentences

involving transitive verbs with two third person singular argument noun phrases, in

order to avoid ambiguity:

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 9

possible, I will make reference to the way that each scholar analyzes

third person singular, which is crucial to examine the relative order

among pronominal affixes.

According to Riggs (1852: 30), when a verb contains forms of

both series, the stative series precedes the active series11. Apart from

this general rule, he adds an exception formed by the first person

plural affix uŋ, which is always placed before the second person affix

ni or ya, whether the form is active or stative. Later, Riggs (1893: 57)

posits another rule: when one personal pronoun represents the

subject and another represents the object of the same verb, the first

person, regardless of its grammatical function, is placed before the

second. Moreover, wičha always precedes the rest of pronouns. As

regards the third person singular form, although this author does

not explicitly say whether the third person singular affix exists or

not, he mentions, since it is the most common form of expression,

the third person of active verbs is never marked through an

‘incorporated pronoun’ (Riggs, 1852: 10).

Buechel (1939: 39) argues that if two person markers occur on

one and the same verb, these markers follow the order Third-First-

Second person. Regarding the third person pronoun, he states that,

although these «inseparable» pronominal forms, except for the third

person plural form wičha, are not overtly expressed, they are

contained in the verb (1939: 37-40).

Following Riggs, Boas and Deloria (1941: 76) claim that the

order of affixes within the verbal complex in Lakota responds to a

double general rule: the object form always precede the subject

form and the first person always precedes the second. According to

(i) Wičháša kiŋ wíŋyaŋ kiŋ ó-Ø-Ø-kiye

man the woman the STEM-3SG:ACT-3SG:STA-help

‘The man helped the woman.’

(ii) Wíŋyaŋ kiŋ wičháša kiŋ ó-Ø-Ø-kiye

Man the woman the STEM-3SG: ACT-3SG:STA-help

‘The woman helped the man.’

11Riggs (1852: 30) uses the terms ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ for ‘stative’ and

‘active’ respectively.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 10

these authors´ analysis (Boas and Deloria, 1941: 76), there is no

third person pronoun12, but they do not mention whether it is

specified covertly or whether it simply does not exist. Furthermore,

they admit (Boas and Deloria, 1941: 77) the existence of some

exceptions to this generalization, such as the special case of ‘neutral

verbs with two objects’ or stative transitive verbs including two

stative cross-referencing forms.

About thirty years later, Van Valin retakes the task of analysing

the order of elements in the Lakota verb and describes this order as

templatic, with object forms preceding subject forms13 (1977: 6). As

exception he mentions the case of the ‘we-you (singular)’ and ‘we-

you (plural)’ forms, which are represented by the affix combination

uŋ-ni-… and uŋ-ni-…(pi) respectively. He analyses Lakota affixal

person markers as pronominal arguments, relying on their

complementary distribution as evidence. He states (1977: 12) that

verbs mark third person covertly and represents it through a zero

form, except for the third person plural animate object, wičha.

Schwartz (1979: 8) suggests that the third person verbal affix

always precedes the first person affix, both of which precede the

second person affix. Therefore, a Third-First-Second person

hierarchy determines the order of cross-referencing forms.

Although she does not explicitly indicate whether the third person

singular marker exists or not, she does point out that the third

person is not represented by an affix (Schwartz, 1979: 7).

Miner (1979: 37) claims that subject affixes are preceded by

object affixes, except in the sequence first person- second person

singular or plural. Regarding the marking of the third person, this

author points out that the third person singular form has a zero

affix (Miner, 1979: 36).

According to Williamson (1979: 30) the order of the verbal

prefixes in this language depends on person rather than grammatical

12

It must be assumed that they are referring to pronominal affixes, rather than

pronouns.

13

Van Valin regards the notions of subject and object as irrelevant, choosing

instead to rely on semantic macro-roles of Actor and Undergoer.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 11

relation and the ordering hierarchy is Third-First-Second person.

She arranges all the verbal prefixes (including a wide range of

different markers such as locative, instrument, benefactive, dative,

reflexive, reciprocal, agreement, etc.) in fixed slots and differentiate

between those prefixes that alter the argument structure (e.g. wa,

locative, instrument, wičha, etc.) and those that satisfy it (e.g. dative,

benefactive, person agreement markers). She recognizes a verb class

of ‘double-object’ predicates, which have two arguments, both of

them in the stative form (Williamson, 1979: 85-86). Regarding this

type of verbs, she agrees with Boas and Deloria that there is a fixed

order for the two stative cross-referencing forms in transitive stative

verbs and therefore an ambiguity regarding their meaning

(Williamson, 1979: 86). With respect to the marking of the third

person, Williamson mentions that the third person singular

pronominal affix is null and that inanimates are never marked

(Williamson, 1979: 73).

Shaw (1980: 12) assumes a basic subject + object + verb NP

order for Dakota, which, owing to the possible cases of ambiguity,

is the primary indicator of grammatical relations. She argues that

the pronominal order in Dakota languages is determined by the

surface template third-first-second, regardless of the subject - object

functions of the pronouns. Likewise, she also recognizes the

exceptional situation illustrated in ‘double-object’ verbs. In order to

adequately account for such exceptional order, she posits that the

ordering principle that determines the surface structure order of the

pronominal prefixes in these languages is as follows: wičha –uŋ(k) –

ni/čhi – ma/wa – ya. This scholar notes that the third person is

always unmarked, with the only exception being the verbal prefix

wičha, which codes animate plural objects (Shaw, 1980: 10-11).

De Reuse (1983: 88) states the order of the NP arguments in

Lakota is as follows: subject + object + V, when two NPs are

present and, regarding the order of affixes, he mentions that the

affix order in this language is usually object + subject + verb.

Likewise, this linguist analyzes third person singular forms as zero

pronominal affixes.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 12

Rood and Taylor (1996: 468) posit the object + subject affix

order, although they list a number of exceptions to this rule, such

as: uŋ precedes all affixes except wičha; the portmanteau form či for

the combination first person agent-second person singular or plural

patient; some forms in y-stem and nasal stem intransitive verbs (e.g.

yal and yan); the position of the enclitic pluralizer pi; the ambiguity

caused by the fixed order shown by affixes in stative verbs with two

objects. Regarding the latter exception, they attribute a rigidly fixed

order second person + first person to the verbal affixes in these

sentences, that is ni always precedes ma regardless of the

grammatical function, hence this ordering always leads to semantic

ambiguity. Although they affirm that a Third + Second + First

person order would account for these exceptions, they restrict the

number of affix ordering principles operating in a language to one.

Accordingly, and despite the aforementioned exceptions, they

favour the object-subject order. Rood and Taylor posit that, except

for the third person plural animate (i.e. wičha), there is no affix for

third person (Rood and Taylor, 1996: 465) and represent the third

person singular participants through a null marker in their chart

containing combinations between the two affixes (Rood and

Taylor, 1996: 466), which appears to imply that the remaining third

person markers are covertly specified.

Ingham (2003: 19) argues that the patient marker usually

precedes the agent when partiticipants playing these two semantic

roles co-occur in a sentence, with the exception that the first person

plural marker uŋ(k) always precedes second person, irrespective of

its semantic role. As regards the marking of the third person

singular, he simply mentions that it lies unmarked (Ingham, 2003:

18).

Rankin (2006: 542) claims that patient precedes agent regardless

of person. This author mentions that third person singular is never

marked, although he represents it through a zero marker in the chart

including a hypothetical ordering of the Dakotan prefixes (Rankin,

2006: 541).

Woolford (2008: 3), observing a distinction between the

behaviour exhibited by stative and active forms, which he classifies

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 13

as clitics and agreement markers respectively, argues that, when

more than one syntactic clitic is present within the verbal complex,

the order of these forms is determined by two types of alignment,

that is a plural + dual + singular number hierarchy and a Third +

Second + First person hierarchy, with number having precedence

over person.

The grammar section of the Lakȟota Language Consortium

dictionary (2011: 771) provides a chart including all the possible

combinations of verbal affixes in transitive constructions but does

not make reference to any specific ordering principle. In this chart,

the cross-referencing of third person singular participants is

indicated by null marker Ø.

3. Discussion on the ordering of affixes in monotransitive

constructions

There are two main accounts of the relative order of the relative

order of pronominal affixes: one makes reference to the person and

the other to the grammatical function and/or semantic role14 of the

argument with which the pronominal affix corefers. The only

exception to the first principle is found in the situation involving

the transitive stative verbs or also called ‘double-patient’ verbs15,

while the combination of a first person plural subject marker uŋ and

a second person singular or plural object marker ni forms the only

14 The only semantic roles that are taken into account are agent and patient in a

monotransitive construction and agent and recipient or beneficiary in a ditransitive or

benefactive construction, since Lakota shows secundative alignment and, therefore,

the recipient or beneficiary is considered the primary object and is coded in the same

way as the monotransitive patient, but differently from the ditransitive theme, which

is never overtly cross-referenced. The dative and benefactive markers ki ‘to’ and kíči

‘for’ are therefore not taken into consideration in the ordering since they behave as

applicative markers, that is, they indicate that a new participant has been added to the

argument structure of the predicate (i.e. the recipient or beneficiary) and that the overt

reference to another participant (i.e. the theme) has been suppressed, and their form

remains invariable regardless of the person of the participant functioning as primary

object.

15 This term is rather misleading since it implies that the two arguments of these

verbs have the semantic role of patient, when this is not correct.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 14

exception to the second principle. Thus, basically, both principles

appear to be equally simple and general.

As regards transitive stative verbs, it has generally been believed

(Boas and Deloria, 1941; Williamson, 1979; Rood and Taylor, 1996;

among others) that this class of verbs presents two stative forms as

affixes, and that the order of these cross-referencing pronominal

affixes follow a rigidly fixed order second person + first person.

Consequently, these sentences are believed to be ambiguous with

regard to which prefix is interpreted as subject and which as object

agreement, thereby having two diametrically different translations:

(1) Iye-ni-ma-čheča

INSTR16-2SG:STA-1SG:STA-resemble

‘I resemble you.’ or ‘You resemble me.’ (Boas and Deloria,

1941: 77)

(2) I-ni-ma-ta

INSTR- 2SG:STA-1SG:STA-proud of

‘I am proud of you.’ or ‘You are proud of me.’ (Boas and

Deloria, 1941: 77)

The main problem concerning the analysis of these forms lies in

the fact that they are extremely rare even in older written sources

and that there is hardly any evidence of early stages of development

in this language, insofar as it was first put into written form by

missionaries around 1840. It is therefore very difficult to

reconstruct the pre-history of this construction in this language and,

consequently, the only way to access to the language historical

development is an indirect one: the comparison with other, related

languages within the same family. Thus, after consulting native

informants speaking three different but closely related Sioux

languages, that is, Sičhángu (Brulé) Lakota, Ȋyȃrhe (Stoney) Nakoda,

16 Cumberland (2005: 224) classifies prefixes such as a, i, or o as locatives with the

meanings of ‘at/on’, ‘by means of / with / against / in reference to’, and ‘in/within’

respectively. She also adds that sometimes two different locative prefixes may co-

occur, being then separated by an epenthetic -y- or a glottal stop.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 15

and Sisíthuŋwaŋ-Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ (Sisseton-Wahpeton) Dakota, I

have found out that some speakers consider it archaic but also

grammatically correct to alter the order of these pronominal affixes

ni-ma on the basis of the grammatical function of the arguments

corefering with them. Thus, the following examples in Lakota (3a

and 3b), Nakoda17 (4a and 4b) and Dakota (5a and 5b) illustrate

how it is possible to find occurrences of pronominal affixes that

follow the order ma-ni:

(3) a. I-ni-ma-štušte ye/yelo

INSTR-2SG: STA-1SG: STA-tired of IF

‘I am tired of you.’

b. I-ma-ni-štušte ye/yelo

INSTR-1SG: STA-2SG: STA- tired of IF

‘You are tired of me.’

(4) a. I-ni-ma-stusta

INSTR-2SG: STA-1SG: STA-tired of

‘I am tired of you.’

b. I-ma-ni-stusta

INSTR-1SG: STA-2SG: STA-tired of

‘You are tired of me.’

17

West (2003: 107) provides the following examples in Assiniboine Nakota that

confirm this hypothesis:

(i) I-ni-ma-stusta

INSTR-2SG: STA-1SG: STA-tired of

‘You are tired of me.’

(ii) I-ma-ni-stusta

INSTR-1SG: STA-2SG:STA- tired of

‘I am tired of you.’

However, as will be argued below, unlike her, I argue that the order of the two stative

forms is object + subject, rather than subject + object.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 16

(5) a. I-ni-ma-štušte ye/do18

INSTR-2SG: STA-1SG: STA-tired of IF

‘I am tired of you.’

b. I-ma-ni-štušte ye/do

INSTR-1SG: STA-2SG: STA- tired of IF

‘You are tired of me.’

The forms above are part of a more ancient period of this

language. This can be confirmed by the fact that, for other examples

of transitive stative verbs, such as ítaŋ ‘be proud of’ or iyéčheča

‘resemble’, my native consultants favour a more modern

expression19, which involves the use of independent personal

pronouns and a causative construction:

(6) Niyé i-ní-ma-taŋ-ya

you INSTR-2SG:STA-1SG:STA-proud.of-CAUS

‘You are proud of me.’

(7) Niyé i-ní-ma-čheča-ya

you INSTR-2SG:STA-1SG:STA-resemble-CAUS

‘You resemble me.’

Following Williamson (1984: 35), I claim that these stative verbs

containing two object forms are indeed intransitive verbs that

become transitive by means of the addition of an oblique argument.

This argument is considered oblique because it is preceded by a

prepositional prefix, which always triggers objective case. Thus,

these ‘transitive’ stative verbs, like ištúšta ‘be tired of’, ištéčA ‘be

ashamed of’ or iyókiphi ‘be pleased with’ can be compared to other

transitive active verbs that also require oblique arguments, such as

ikȟókipȟA ´be afraid of`, iwáŋyaŋkA ‘look at sth in regard to /

18 In order to signal IF, Lakota uses a great number of enclitics, which vary

according to the type of IF, the gender and number of the speaker, and the ending of

the preceding word. In this case, the IF markers ye/do indicate declarative IF, the

example being uttered by a man or a woman respectively.

19 Unless indicated, all the examples provided belong to the Lakota dialect.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 17

examine’, iwóglakA ‘tell sth about’, anáwizi ‘be jealous of’ or iȟát´A

‘laugh at’. These transitive uses of both stative and active verbs are

either not recognized or regarded as archaic by most speakers today.

They could therefore be considered a reflection of a more synthetic

period in the evolution of this language. Accordingly, these prefixes,

such as i- or a-, may have lost their original locative or instrumental

meaning and have now acquired a new meaning. In the case of the

prefix i-, although it is believed to have originally meant ‘at /

against’, its modern meanings appear to be those of ‘with / on

account of / with reference to / with respect to’ (Buechel, 1936:

116; Cumberland, 2005: 224). Thus, formerly, when the language

had a more synthetic nature, these locatives and instrumental

markers were originaly prefixed to the verbal complex bearing their

object. Over time, in its development towards a more analytic

language, Lakota started to make use of postpositions, which

attracted their objects by taking them out of the verbal complex.

Subsequently, these postpositions have inserted the object / object

marker / object pronoun in front of the adposition, as can be

observed in the following pair of sentences:

(8) a. Ikhiyéla uŋ-ya-thi-pi

LOC 1: STA-2SG: ACT-live-PL

‘You live near us.’

b. Uŋk-ikhiyéla-pi ya-thi

1: STA-LOC-PL 2SG: ACT-live

‘You live near us.’

Example (8a) is believed to contain an older form than that in

(8b) and therefore this could reflect the evolution of this language

from a polysynthetic nature to a more analytic one. An even more

ancient feature of this language could have consisted in having the

adposition attached to the verbal complex as a prefix, as the verb

thi in (8a) shows.

Thus, forms like inimataŋ ‘I am proud of you’ were originally

formed by a prepositional affix along with its object plus the

obligatory argument of the non-verbal predicate atáŋ ‘proud of’. In

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 18

summary, instead of being transitive stative verbs, they would be

considered intransitive stative verbs with obliques. The problem is

that, as both the oblique argument and the argument which is

obligatorily subcategorized for by the verb occur in stative form,

there is no morphosyntactic distinction today between these two

arguments in terms of case.

Taking this assumption into consideration, we can assume that

it was formerly also possible to build similar constructions, where

the two stative cross-referencing forms involve the forms wičha and

uŋ(k), as illustrated by the following (hypothetical) constructions:

(9) ??? I-ma-wičha-štušta

INSTR-1SG: STA-3PL: STA-tired.of

‘They are tired of me.’

(10) ??? I-ni-uŋ-štušta-pi

INSTR-1SG: STA-1: STA-tired of-PL

‘We are tired of you.’

Nevertheless, although the examples (3-7) appear to confirm

this hypothesis, far more work is required before it can be

substantiated.

Finally, as third person singular arguments are never overtly

cross-referenced on the Lakota verb, the remainder of the section

attempts to provide, from a diachronic perspective, an explanation

of the status of the third person plural form wičha, which serves to

define more precisely the principle determining the ordering of

pronominal affixes in Lakota.

Although it is not easy to determine the behaviour of the form

wičha, the fact that there exists an homonymous term meaning

‘human or man’ could reflect a case of grammaticalization20 by

20

Rankin (2006: 542) claims that Proto-Siouan *wų•k- ‘man, person’ was

incorporated and grammaticalized early, becoming the third person plural marker.

According to Koontz (p.c.), wičha could come from wičhaša (Santee Dakota > wičhasta)

‘man’. Heine and Kuteva (2002: 208) also cite a similar example of grammaticalization

from Lendu, a language where the lexical word ‘people’ is grammaticalized to a third

person plural pronoun.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 19

which the noun wičha, through different stages of development21,

evolved into a syntactic clitic, which attached to the left edge of

many verbs cross-referencing an argument expressing a non-

specific collective noun (e.g. wičháčheya ‘wail’, wičhahAŋ ‘stand’,

wičhíyokiphi ‘be happy’, wičhóthi ‘camp’, etc.), and finally became a

pronominal affix standing for a third person plural animate subject

and object marker of the stative series.

Williamson (1984: 78) appears to consider wičha a clitic, that is a

suppletive form for pi, which in broad terms mark objects and

subjects respectively since, while wičha is mostly restricted to third

person plural animate objects22, pi occurs mostly with all plural

animate subjects23.

Pustet and Rood (2008: 344-345) also provide evidence that this

marker wičha can be used non-referentially:

(11) Aŋpétu iyóhila owáchekiye kiŋ lená wa24-Ø-káȟla-pi

na hená

day each church the these STEM-3: STA-ring-

PL and those

wichá-Ø-ȟa-pi25

people-3:ACT-bury-APD

‘Every day the church bells rang and people were

buried/there were funerales.’

21

Hopper and Traugott (2003: 7)´s ‘cline of grammaticalization’ illustrates the

various stages of the form: content word → grammatical word → clitic → inflectional

affix.

22

Wičha also crossreferences third person plural animate collective subjects in

intransitive stative verbs and in some intransitive active verbs.

23

This is a broad generalization since, although pi does not occur with third person

plural collective objects, it does crossreference first and second person plural objects

in transitive verbs.

24

Wa- is considered an inanimate patient dereferentializer in Pustet and Rood

(2008: 342) or an indefinite object marker in LLC (2011: 578).

25 Pustet and Rood (2008: 336) regards pi as an ‘agent impersonalizer’ or AGIPS

when it does not refer to a specific animate plural referent. It seems to have an agent-

suppressing function and therefore it does not convey the idea of plurality.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 20

In this example, wičha does not refer to any specific plural

referent and consequently it functions as an ‘animate patient

dereferentializer’ or APD (Pustet and Rood, 2008: 344). In this use,

it would not be possible to insert an third person plural animate

patient corefering with wičha because it has suppressed reference to

this patient.

Thus, the hypothetical course of events would reflect the

following progression: a content word26 develops firstly into

dereferentializing clitic (or affix), with no overtly specified

referent27, and finally into a grammatical morpheme indicating third

person plural, which cross-references a plural argument NP

functioning as patient that can be both overtly or covertly specified.

In this last step, it does not only corefer with patients in transitive

constructions, but also with collective agents of most stative verbs

and some active verbs28.

To summarize, this grammatical morpheme developed out of a

lexical item or content word with a generalized meaning – an

important condition for grammaticalization – and prefixed to the

left side of the verb, further away from the verb root than the

inflectional morphemes (e.g. person agreement markers). What

seems evident is that, regardless of whether wičha is either a syntactic

clitic or an agreement marker, this pronominal argument occurs at

the left edge of the verbal complex. Therefore, it precedes all the

true agreement markers forms. Hence it can now be considered a

mirror image of the plural number clitic pi, which always follows the

verb. This supports Mithun (2000)´s assumption that the order of

26 Boas and Deloria (1941: 76) considers wičha not a pronoun but a noun

meaning ‘person’ which has grammaticalized.

27 E.g.:

(i) Wičh(a)-íyo-Ø-kiphi i-bl-utȟe

people-INSTR-1SG:STA-be.pleased STEM-1SG:ACT-try

‘I try to please people.’

28 E.g.: Wičhášiče ‘They (as a group) are bad.’ or Wičhawákhiya ‘They (as a group)

confer in council.’

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 21

morphemes in a language appears to reflect their historical order of

grammaticalization, in such a way that those affixes closest to the

root are indeed the oldest, and those on the periphery of words can

be seen to be more recent additions.

Accordingly, bearing in mind that wičha did not originally behave

as a true agreement marker and that the third person is not overtly

marked in this language, and consequently, it is impossible to

discern its position within the verbal complex, it seems plausible to

conclude that the ordering of the pronominal affixes marking

person can be reduced to the analysis of the combination between

first person and second person forms. Except for the combination

first person singular agent and second person singular or plural

patient, both of which are represented by the portmanteau form čhi,

the remaining combinations render the order first person + second

person, which appears to have been the original ordering

principle29.

4. Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to tackle the problem of the linear

ordering of pronominal affixes in Lakota. After revising all the

existent literature on this issue, and taking into account that, firstly,

the plural clitic -pi can not be included in the analysis since it has no

bearing on the relative order of affixes, secondly, the form wičha

must not be included either, since it was not an affix in its origin

and therefore its position reflects its order of attachment, and

finally, third person singular is never marked overtly on the Lakota

verb, I conclude that we can only analyze affix order in this language

diachronically and that the search for an ordering principle of

affixes in this language must be reduced to the one exhibited by the

combination between first and second persons, which leads to the

29 Following Buechel (1939: 39), I argue that the portmanteau form čhi is indeed a more

modern form, the original form being the expected combination first person + second

person wa-ni.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 22

order first person + second person. Consequently, this conclusion

aims to bring the long-standing debate regarding the ordering of

pronominal affixes to an end.

5. Bibliographic references

Boas, Franz and Deloria, Ella Cara (1941): Dakota Grammar, Sioux

Falls, South Dakota, Dakota Press.

Buechel, Eugene (1924): Bible history in the language of the Teton Sioux

Indians, New York, Benziger Brothers.

––– (1939): A Grammar of Lakota: the language of the Teton Sioux

Indians, Saint Francis Mission, South Dakota, Rosebud

Educational Society.

––– (1978): Lakota tales and texts, Pine Ridge, South Dakota, Red

Cloud Indian School.

Buechel, Eugene and Manhart, Paul (20022): Lakota Dictionary:

Lakota-English/English-Lakota. New Comprehensive Edition,

Nebraska, University of Nebraska Press.

Deloria, Ella Cara (20062): Dakota texts, Nebraska, University of

Nebraska Press.

De Reuse, Willem J. (1983): A grammar of the Lakhota Noun Phrase,

Master´s Thesis, University of Kansas.

––– (1994): «Noun incorporation in Lakota (Siouan)», International

Journal of American Linguistics, Chicago, University of Chicago,

60, pp. 199–260.

Hale, Ken (1972): «A new perspective on American Indian

Linguistics», in Ortiz, Alfonso, ed., New Perspectives on the

Pueblos, Alburquerque, New Mexico, University of New

Mexico Press, pp. 87-103.

Heine, Bernd and Kuteva, Tania (2002): World lexicon of

grammaticalization, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hopper, Paul J. and Traugott, Elizabeth C. (2003):

Grammaticalization, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Ingham, Bruce (2003): Lakota, Lincom Europa: München.

Lakota Language Consortium (20112): New Lakȟota Dictionary,

Bloomington: Lakota Language Consortium.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 23

Legendre, Geraldine and Rood, David S. (1992): «On the

interaction of grammar components in Lakhota: Evidence

from Split Intransitivity», Berkeley Linguistics Society, Berkeley,

California: University of California Berkeley, 18, pp. 380-394.

Miner, Kenneth L. (1979): «Discussion: the order of Dakota person

affixes: the rest of the data», in Glossa, Gurabo, Puerto Rico,

Universidad del Turabo, 13, pp. 35-42.

Mithun, Marianne (2000): «The reordering of morphemes», in

Gildea, Spike, ed., Reconstructing Grammar: Comparative

Linguistics and Grammaticalization, Amsterdam, John

Benjamins, pp. 231–255.

Pustet, Regina and Rood, David S. (2008): «Argument

dereferentialization in Lakota», in Donohue, Mark and Søren

Wichmann, eds., The Typology of semantic alignment, Oxford,

Oxford University Press, pp. 334-356.

Rankin, Robert L. (2006): «The interplay of synchronic and

diachronic discovery in Siouan grammar-writing», in Ameka,

Felix K., Alan Dench and Nicholas Evans, eds., Catching

Language: The Standing Challenge of Grammar Writing, Berlin /

New York, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 527-547.

Riggs, Stephen R. (1852): Grammar and dictionary of the Dakota

language, Washington, Smithsonian Institution.

––– (1893): Dakota grammar, texts and ethnography, Washington,

Government Printing Office.

Rood, David S. and Taylor, Allan R. (1996): «Sketch of Lakhota, a

Siouan language», in Goddard, Ives, ed., Handbook of North

American Indians: Languages, Washington, Smithsonian

Institution, 17, pp. 440-482.

Schudel, Emily (1997): «Elicitation and analysis of Nakoda texts

from Southern Saskatchewan», M.A. Thesis, Regina,

Saskatchewan, University of Regina.

Schwartz, Linda (1979): «The order of Dakota Person Affixes: an

evaluation of alternatives», Glossa, Gurabo, Puerto Rico,

Universidad del Turabo, 13, pp. 3-11.

Shaw, Patricia A. (1980): Theoretical issues in Dakota phonology and

morphology, New York, Garland.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

Avelino Corral Esteban: The Ordering Of Lakota Verbal Affixes 24

Van Valin, Robert D. Jr. (1977): «Aspects of Lakhota syntax. A

study of Lakhota syntax and its implications for universal

grammar», Ph.D., University of California at Berkeley.

––– (1985): «Case marking and the structure of the Lakhota clause»,

in Nichols, Johanna and Anthony Woodbury, eds., Grammar

Inside and Outside the Clause, Cambridge, Cambridge University

Press, pp. 363-413.

Van Valin, Robert D. Jr. and Foley, William (1980): «Role and

Reference Grammar», in Moravcsik, Edith A. and Jessica R.

Wirth, eds., Current Approaches to Syntax. Syntax and Semantics,

New York, Academic Press, 13, pp. 329-352.

West, Shannon L. (2003): «Subjects and objects in Assiniboine

Nakoda». Ph.D. Thesis. University of Regina.

Williamson, Janis (1979): «Patient marking in Lakhota and the

Unaccusative Hypothesis», Papers from the Fifteenth Regional Meeting

of the Chicago Linguistic Society, Chicago, University of Chicago.

––– (1984): «Studies in Lakhota Grammar», Ph.D. Thesis,

University of California.

Woolford, Ellen (2008): Active-Stative Agreement in Lakota: person and

number alignment and portmanteau formation, Amherst,

Massachusetts, University of Massachusetts.

[Dialogía, 9, 2015, 4-24]

También podría gustarte

- Fonología segmental:: procesos e interaccionesDe EverandFonología segmental:: procesos e interaccionesAún no hay calificaciones

- Seminario de LinguísticaDocumento23 páginasSeminario de LinguísticaDenice CulquiAún no hay calificaciones

- Nominalización en OtomíDocumento42 páginasNominalización en OtomíIxchéel PilónAún no hay calificaciones

- El caso morfológico en los sustantivos de las lenguas amerindias: un estudio areotipológicoDe EverandEl caso morfológico en los sustantivos de las lenguas amerindias: un estudio areotipológicoAún no hay calificaciones

- SOCIOLING Arias & Corvalan ResumenDocumento14 páginasSOCIOLING Arias & Corvalan ResumenBarbaraMaccariAún no hay calificaciones

- Negacion en AwapitDocumento16 páginasNegacion en AwapitFranz MontillaAún no hay calificaciones

- Tipología y Universales LingüísticosDocumento50 páginasTipología y Universales LingüísticosMaria Calderon AgueroAún no hay calificaciones

- Trabajo Finalito Finalizo El de VerdacitoDocumento26 páginasTrabajo Finalito Finalizo El de VerdacitoelmerAún no hay calificaciones

- МКР лексикологіяDocumento12 páginasМКР лексикологіяMaria MalinovskaAún no hay calificaciones

- Montes. Los Nombres de Las Plantas. 2001 PDFDocumento39 páginasMontes. Los Nombres de Las Plantas. 2001 PDFNatalia AngelAún no hay calificaciones

- El Orden de Los Constituyentes en Verbos Latinos TrivalentesDocumento16 páginasEl Orden de Los Constituyentes en Verbos Latinos TrivalentesJaguar 2013Aún no hay calificaciones

- Sanchez Arroba Maria ElenaDocumento17 páginasSanchez Arroba Maria ElenaCarmen Méndez SerraltaAún no hay calificaciones

- Manual de Morfología EspañolaDocumento95 páginasManual de Morfología EspañolaGabu1995Aún no hay calificaciones

- LéxicoDocumento45 páginasLéxicoSalma AarabAún no hay calificaciones

- 11 11 1 PBDocumento37 páginas11 11 1 PBmysterious gyalAún no hay calificaciones

- TLSE-Modulo3 Curso 3. El Verbo: La Enseñanza y El Aprendizaje de Un Contenido Escolar Clásico (1º A 6º/7º)Documento84 páginasTLSE-Modulo3 Curso 3. El Verbo: La Enseñanza y El Aprendizaje de Un Contenido Escolar Clásico (1º A 6º/7º)Mirta ColoschiAún no hay calificaciones

- Romero, D. 2013a-El Análisis Lingüístico en El EstructuralismoDocumento7 páginasRomero, D. 2013a-El Análisis Lingüístico en El EstructuralismovalAún no hay calificaciones

- Monografia Morfo Final PDFDocumento11 páginasMonografia Morfo Final PDFBrandon Luis Quispe TinocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Gramaticalizacion y Polisemia Del SufijoDocumento17 páginasGramaticalizacion y Polisemia Del SufijoBLUE ADDAXAún no hay calificaciones

- Manual de Morfología EspañolaDocumento98 páginasManual de Morfología Españolarommel7554100% (3)

- LEXICODocumento9 páginasLEXICOCarlota GosalvezAún no hay calificaciones

- La Negacion en El Nahualt Del Centro de GuerreroDocumento53 páginasLa Negacion en El Nahualt Del Centro de GuerreroJoaco RamosAún no hay calificaciones

- Actividades Repaso 3Documento10 páginasActividades Repaso 3mickaela filomenaAún no hay calificaciones

- Trabajo Final - Maria AchayaDocumento7 páginasTrabajo Final - Maria AchayaMARIA FERNANDA ACHAYA ORMEÑOAún no hay calificaciones

- Victor HugoDocumento9 páginasVictor HugoNoé S. BenitesAún no hay calificaciones

- Lectura 7 - El Verbo Poder en El Discurso Cientifico PDFDocumento16 páginasLectura 7 - El Verbo Poder en El Discurso Cientifico PDFAdriana PérezAún no hay calificaciones

- Sujeto en El Maya Yucateco e Input PDFDocumento19 páginasSujeto en El Maya Yucateco e Input PDFengelsblutAún no hay calificaciones

- Resumen Coloquio InviernoDocumento5 páginasResumen Coloquio InviernoMafer PérezAún no hay calificaciones

- ErgatividadDocumento22 páginasErgatividadCarolina Rodríguez AlzzaAún no hay calificaciones

- 53771-Texto Del Artículo-228241-1-10-20090310Documento16 páginas53771-Texto Del Artículo-228241-1-10-20090310Gabriel AgrestaAún no hay calificaciones

- La Voz Pasiva en EspañolDocumento25 páginasLa Voz Pasiva en Españolbryant diazAún no hay calificaciones

- El Adjetivo en YukpaDocumento23 páginasEl Adjetivo en YukpaLuis oquendoAún no hay calificaciones

- SilábicaDocumento5 páginasSilábicanangina gabineteAún no hay calificaciones

- 2012 Belloro 2012 Pronombres Cliticos DiDocumento35 páginas2012 Belloro 2012 Pronombres Cliticos DiDaniel RomeroAún no hay calificaciones

- La Interpretacion de Sintagmas Preposicionales EscDocumento30 páginasLa Interpretacion de Sintagmas Preposicionales EscGabriel AgrestaAún no hay calificaciones

- Clasificación de Categorías Gramaticales en La Lengua Materna EspañolDocumento11 páginasClasificación de Categorías Gramaticales en La Lengua Materna EspañolDuban GarzonAún no hay calificaciones

- Censabella y Carpio. Tipos de Coordinantes en Toba (Guaycurú)Documento18 páginasCensabella y Carpio. Tipos de Coordinantes en Toba (Guaycurú)Araceli PolisenaAún no hay calificaciones

- Apunte Lengua Castellana Corredor y MartilleroDocumento87 páginasApunte Lengua Castellana Corredor y MartilleroMaría Julia Ogna EgeaAún no hay calificaciones

- Los Pronombres Personales Del Mixteco: Un Estudio en Dos VariantesDocumento18 páginasLos Pronombres Personales Del Mixteco: Un Estudio en Dos VarianteskantzakataAún no hay calificaciones

- Haplologia en Los Sufijos de Posesion enDocumento30 páginasHaplologia en Los Sufijos de Posesion engendrikmhAún no hay calificaciones

- Ensayo Una Mirada A La Linguistica DescriptivaDocumento5 páginasEnsayo Una Mirada A La Linguistica Descriptivayennypaola123Aún no hay calificaciones

- Semantica Linguística Aplicada EvangelistaDocumento28 páginasSemantica Linguística Aplicada EvangelistaBeatriz Helena GomezAún no hay calificaciones

- Síncopa de La Oclusiva Dental Sonora D en Posición Intervocálica Del Sistema de Lengua Del Español ChilenoDocumento10 páginasSíncopa de La Oclusiva Dental Sonora D en Posición Intervocálica Del Sistema de Lengua Del Español ChilenoTempus Fugit MoortusAún no hay calificaciones

- Acerca de Las Lenguas Factitivas - El Sufijo - Tah en YaquiDocumento30 páginasAcerca de Las Lenguas Factitivas - El Sufijo - Tah en YaquiGenaro Israel Ab'äj Vot'anAún no hay calificaciones

- Variación en Forma Morfológica de Los Pronombres de Primera y Segunda Persona de Plural Antonio FábregasDocumento30 páginasVariación en Forma Morfológica de Los Pronombres de Primera y Segunda Persona de Plural Antonio FábregasArmando Garcia TorresAún no hay calificaciones

- Sustantivo SintaxisDocumento8 páginasSustantivo SintaxisDalia Fernanda XN TrejoAún no hay calificaciones

- Lingüística Taller 1 (Solucionado) - María Teresa Polo SarmientoDocumento8 páginasLingüística Taller 1 (Solucionado) - María Teresa Polo SarmientoMaría Teresa PoloAún no hay calificaciones

- Dialnet ElTemaEnIEnGriegoAntiguo 5774906Documento28 páginasDialnet ElTemaEnIEnGriegoAntiguo 5774906armavirumqueAún no hay calificaciones

- 03 A Semantica OracionalDocumento30 páginas03 A Semantica OracionalHugo Nava100% (1)

- Clase 7 ENS 1Documento7 páginasClase 7 ENS 1Rocío DeniseAún no hay calificaciones

- De Borocotizar A Botonear Un AcercamientDocumento15 páginasDe Borocotizar A Botonear Un AcercamientAgustin GoinAún no hay calificaciones

- Karolayn Miranda Lengua CatellanaDocumento8 páginasKarolayn Miranda Lengua CatellanaKaren SierraAún no hay calificaciones

- Rev. Ad. - Sobral - Análisis Comparativo de La Colocación Del Pronombre Átono de 3 Persona en Gallego y en RumanoDocumento17 páginasRev. Ad. - Sobral - Análisis Comparativo de La Colocación Del Pronombre Átono de 3 Persona en Gallego y en RumanoIlinca IlianAún no hay calificaciones

- Género GramaticalDocumento19 páginasGénero Gramaticaledson chavezAún no hay calificaciones

- Fundamentos de La Lingüística TeóricaDocumento8 páginasFundamentos de La Lingüística TeóricaNíki De LesbosAún no hay calificaciones

- Cuestiones de LexicologiaDocumento45 páginasCuestiones de Lexicologiataleb.adeel84Aún no hay calificaciones

- Universidad Estatal Del Sur de ManabíDocumento9 páginasUniversidad Estatal Del Sur de ManabíIsaack ErickAún no hay calificaciones

- Material de GramáticaDocumento20 páginasMaterial de GramáticaDoris de EspinaAún no hay calificaciones

- ESPAÑOLDocumento71 páginasESPAÑOLProf ARTEMIO CGAún no hay calificaciones

- Drunvalo Melchizedek - Serpiente de LuzDocumento162 páginasDrunvalo Melchizedek - Serpiente de LuzMaximo100% (68)

- Aborigenes SiouxDocumento16 páginasAborigenes SiouxJUR29100% (1)

- Medicina Indígena y Males InfantilesDocumento48 páginasMedicina Indígena y Males InfantilesYopYopAún no hay calificaciones

- 126 - 30 MayoDocumento4 páginas126 - 30 Mayomarisol romeroAún no hay calificaciones

- Guide#10-Relative ClausesDocumento4 páginasGuide#10-Relative Clausesosney arguello celisAún no hay calificaciones

- Menegotto 2020. Morfosintaxis NominalDocumento28 páginasMenegotto 2020. Morfosintaxis NominalJeanette GerpeAún no hay calificaciones

- 8 - Avance de Quechua - AgostoDocumento6 páginas8 - Avance de Quechua - AgostoGUILMER MENDOZA UCHAROAún no hay calificaciones

- Castellano Segundo Trabajo Verano 2013Documento260 páginasCastellano Segundo Trabajo Verano 2013Laura Morales SelasAún no hay calificaciones

- Perfekt (Cuadernillo Resumen) + TKMLDocumento14 páginasPerfekt (Cuadernillo Resumen) + TKMLLaura Martin MorenoAún no hay calificaciones

- Tarea 6 - de Español 1 - UAPADocumento4 páginasTarea 6 - de Español 1 - UAPACentro de Internet R&RAún no hay calificaciones

- Prácticas Del Lenguaje 12 y 13 de Agosto 6tob TTDocumento2 páginasPrácticas Del Lenguaje 12 y 13 de Agosto 6tob TTJuan Cruz EmmaAún no hay calificaciones

- ORACIÓN COMPUESTA Cuadro SinópticoDocumento5 páginasORACIÓN COMPUESTA Cuadro SinópticoJulyeta Mtz JiméneezAún no hay calificaciones

- Clase Vivencial de Polidocencia Actividades - 29 de NoviembreDocumento6 páginasClase Vivencial de Polidocencia Actividades - 29 de NoviembreJulissa Prado BecerraAún no hay calificaciones

- La AcentuacionDocumento44 páginasLa AcentuacionHenry Alexander Choc AcAún no hay calificaciones

- Ejercicios SintagmasDocumento3 páginasEjercicios SintagmasAnnia Elena Rugama CorralesAún no hay calificaciones

- AdverbsDocumento3 páginasAdverbsJosse LazzoAún no hay calificaciones

- Categorías Invariables AdverbioDocumento5 páginasCategorías Invariables AdverbioMara MiñanAún no hay calificaciones

- Gramatica de PortuguésDocumento63 páginasGramatica de PortuguésnabinbishtAún no hay calificaciones

- La Escritura Como Acto Pensa - Unidad - 2Documento20 páginasLa Escritura Como Acto Pensa - Unidad - 2julio alberloAún no hay calificaciones

- Complemento Circunstancial Del PredicadoDocumento7 páginasComplemento Circunstancial Del PredicadoLucio Arbildo RamirezAún no hay calificaciones

- Subordinadas CondicionalesDocumento5 páginasSubordinadas CondicionalesPaola AtienzaAún no hay calificaciones

- Uso de La BDocumento5 páginasUso de La BYolandaAún no hay calificaciones

- Alarcos Llorach Fonologia Espanola PDFDocumento150 páginasAlarcos Llorach Fonologia Espanola PDFbodoque76100% (9)

- Tiempos VerbalesDocumento9 páginasTiempos VerbalesCelia Navarro OrmeñoAún no hay calificaciones

- Subordinadas OracionesDocumento2 páginasSubordinadas OracionesAnonymous XtC0Xi0MBb50% (2)

- Classesby Vaughan A1Documento184 páginasClassesby Vaughan A1esehacker100% (4)

- Fith WorkshopDocumento6 páginasFith WorkshopNelly SanchezAún no hay calificaciones

- Writing TipsDocumento3 páginasWriting TipsInma GarciaAún no hay calificaciones

- Plan de Clase Castellano La Silaba Vocales Abiertas y Cerradas 3Documento8 páginasPlan de Clase Castellano La Silaba Vocales Abiertas y Cerradas 3Ruth CarilloAún no hay calificaciones

- Adjetivo DeterminativoDocumento21 páginasAdjetivo DeterminativoKarla MantillaAún no hay calificaciones

- Clase Psco LingDocumento2 páginasClase Psco LingKarina Andrea Jiménez CartesAún no hay calificaciones

- Manual de La Materia Expresion Oral y Es PDFDocumento120 páginasManual de La Materia Expresion Oral y Es PDFDaiana MaldonadoAún no hay calificaciones

- Ingles - Adverbios Terminados en LYDocumento2 páginasIngles - Adverbios Terminados en LYAleja GuzmanAún no hay calificaciones

- Sintagma VerbalDocumento9 páginasSintagma VerbalLeonardo Mujica QuispeAún no hay calificaciones

- Ortografía correcta del españolDe EverandOrtografía correcta del españolCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (16)

- El lenguaje del cuerpo: Una guía para conocer los sentimientos y las emociones de quienes nos rodeanDe EverandEl lenguaje del cuerpo: Una guía para conocer los sentimientos y las emociones de quienes nos rodeanCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (49)

- Inglés ( Inglés Facil ) Aprende Inglés con Imágenes (Super Pack 10 libros en 1): 1.000 palabras en Inglés, 1.000 imágenes, 1.000 textos bilingües (10 libros en 1 para ahorrar dinero y aprender inglés más rápido)De EverandInglés ( Inglés Facil ) Aprende Inglés con Imágenes (Super Pack 10 libros en 1): 1.000 palabras en Inglés, 1.000 imágenes, 1.000 textos bilingües (10 libros en 1 para ahorrar dinero y aprender inglés más rápido)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (79)

- ¡Aprende chino ya!: El mejor método para principiantes con claves sobre cómo hacer amigos y negociosDe Everand¡Aprende chino ya!: El mejor método para principiantes con claves sobre cómo hacer amigos y negociosCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2)

- Historia sociolingüística de México.: Volumen 1De EverandHistoria sociolingüística de México.: Volumen 1Aún no hay calificaciones

- Introducción a los estudios del discurso multimodalDe EverandIntroducción a los estudios del discurso multimodalCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- Conversación para viaje: PortuguésDe EverandConversación para viaje: PortuguésCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1)

- Guíaburros Aprender Inglés: Vademecum para asentar las bases de la lengua InglesaDe EverandGuíaburros Aprender Inglés: Vademecum para asentar las bases de la lengua InglesaCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (2)

- Inglés ( Inglés Sin Barreras ) Palabras Frecuentes (4 libros en 1 Super Pack): 400 palabras frecuentes en inglés explicadas en español con textos bilingüesDe EverandInglés ( Inglés Sin Barreras ) Palabras Frecuentes (4 libros en 1 Super Pack): 400 palabras frecuentes en inglés explicadas en español con textos bilingüesCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (22)

- Inglés - Aprende Inglés Con Cuentos Para Principiantes (Vol 1): Cuentos Bilingües (Texto Paralelo En Inglés y Español) Para Principiantes (Inglés Para Latinos)De EverandInglés - Aprende Inglés Con Cuentos Para Principiantes (Vol 1): Cuentos Bilingües (Texto Paralelo En Inglés y Español) Para Principiantes (Inglés Para Latinos)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (20)

- Estructura de la magia I (The Structure of Magic I): Lenguage y terapiaDe EverandEstructura de la magia I (The Structure of Magic I): Lenguage y terapiaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (47)

- Semiótica y literatura: Ensayos de métodoDe EverandSemiótica y literatura: Ensayos de métodoCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (3)

- Programa integrado para el desarrollo de la conciencia fonológica y del vocabulario en la lectura inicialDe EverandPrograma integrado para el desarrollo de la conciencia fonológica y del vocabulario en la lectura inicialCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- Diccionario del español de México: Volumen 1De EverandDiccionario del español de México: Volumen 1Calificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- Curso de Inglés: Construcción de Palabras y OracionesDe EverandCurso de Inglés: Construcción de Palabras y OracionesCalificación: 3 de 5 estrellas3/5 (9)

- Inglés - Aprende Inglés Con Cuentos Para Principiantes (Vol 2): Cuentos Bilingües (Texto Paralelo En Inglés y Español) Para PrincipiantesDe EverandInglés - Aprende Inglés Con Cuentos Para Principiantes (Vol 2): Cuentos Bilingües (Texto Paralelo En Inglés y Español) Para PrincipiantesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (6)

- Diccionario de anécdotas, dichos, ilustraciones, locuciones y refranesDe EverandDiccionario de anécdotas, dichos, ilustraciones, locuciones y refranesCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (3)