Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Ar 23748

Ar 23748

Cargado por

Javier PinedaDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Ar 23748

Ar 23748

Cargado por

Javier PinedaCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Contribuyamos con el medio ambiente Segn el Panel Intergubernamental para el Cambio Climtico (IPCC), seis millones de hectreas de bosques

primarios son deforestados cada ao. Esto equivale a la superficie de un estadio de ftbol cada segundo. El cambio climtico es un problema que nos afecta a todos, por lo que todos somos responsables de actuar al respecto. ESAN, escuela de negocios lder en el Per, asume un compromiso con el medio ambiente a travs de acciones concretas que contribuyan a preservar nuestro medio ambiente. Parte de este compromiso es la distribucin de materiales de la semana internacional en formato digital. Con su apoyo, reducimos el consumo de ms de 160 millares de papel, adems de tinta contaminante y folders plsticos. Cada accin cuenta en el cuidado de nuestro medio ambiente. Es el nico que tenemos y por eso agradecemos su colaboracin. Ahora piense en cuntos estadios de ftbol fueron deforestados en el tiempo que le tom leer esta declaracin.

----------------------------------Este material de lectura se reproduce para uso exclusivo de los alumnos de la Escuela de Administracin de Negocios para Graduados ESAN y en concordancia con lo dispuesto por la legislacin sobre derechos de autor: LEY 13714 Art. 69: Pueden ser reproducidos y difundidos breves fragmentos de obras literarias, cientficas y artsticas, y aun la obra entera, si su breve extensin y naturaleza lo justifican; siempre que la reproduccin se haga con fines culturales y no comerciales, y que ella no entrae competencia desleal para el autor en cuanto al aprovisionamiento pecuniario de la obra, debiendo indicarse, en todo caso, el nombre del autor, el ttulo de la obra y fuente de donde se hubiere tomado.

Torres-Moraga, E., Vsquez-Parraga, A.Z. y Barra, C. (2010). How to measure service quality in internet banking. International Journal of Services and Standards, 6 (3-4) pp. 236255.

236

Int. J. Services and Standards, Vol. 6, Nos. 3/4, 2010

How to measure service quality in internet banking Eduardo Torres-Moraga

School of Business, Universidad de Chile, Diagonal Paraguay # 257, Santiago de Chile, Chile Email: eduardot@unegocios.cl

Arturo Z. Vsquez-Parraga*

Department of Marketing, The University of Texas-Pan American, 1201 University Drive, Edinburg, Texas, USA Email: avasquez@utpa.edu *Corresponding author

Cristbal Barra

School of Business, Universidad de Chile, Diagonal Paraguay # 257, Santiago de Chile, Chile Email: cbarra@fen.uchile.cl

Abstract: This study aims at developing and testing a scale that measures service quality in internet banking. The scale is destined to help evaluate the performance of banks using internet platforms in the context of an emerging economy. The research is processed in two stages, a qualitative study on the basis of the Critical Incident Technique and a questionnaire applied to Chilean banks using internet services. The study results in six relevant, valid and reliable dimensions of service quality for internet banking: accessibility/availability, accuracy, products/services quality, responsiveness, security/privacy, and usability. The study yields three significant contributions: (a) consumer feedback relevant to service quality of e-banking services; (b) tested means of evaluating performance in internet banking platforms; and (c) an adaptable scale to various cultural contexts and stages of information systems development. Keywords: services and standards; service quality; internet banking; e-banking; electronic banking; Chile; measures of service quality; accessibility/ availability; accuracy; products/services quality; responsiveness; security/ privacy; usability. Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Torres-Moraga, E., Vsquez-Parraga, A.Z. and Barra, C. (2010) How to measure service quality in internet banking, Int. J. Services and Standards, Vol. 6, Nos. 3/4, pp.236255.

Copyright 2010 Inderscience Enterprises Ltd.

How to measure service quality in internet banking

Biographical notes: Eduardo Torres-Moraga holds a PhD in Business Administration and is Assistant Professor of Marketing at the School of Business at the Universidad de Chile. He has performed scientific research in customer loyalty and e-Commerce. His research has been published in several academic journals such as The International Journal of Bank Marketing, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Journal of Business Research, Internet Research, International Journal of Services and Standards, Health Marketing Quarterly, and Journal of Administrative and Social Sciences. Arturo Z. Vsquez-Parraga is Professor of Marketing and International Business at the University of Texas-Pan American (UTPA). He holds a PhD degree in Economics from the University of Texas at Austin, and a PhD degree in Marketing and International Business from Texas Tech University. He has performed scientific research in strategic marketing, customer loyalty, marketing and business ethics, and strategies of Latin American companies in the USA, and has extensively published in leading journals in marketing, international business and business ethics. Cristbal Barra is Instructor in the field of Marketing at the School of Business of the University of Chile. He holds a Master of Science degree in Marketing from the University of Chile. His specific areas of research are customer trust, brand extensions and multidimensional constructs in relationship marketing. He has published articles in journals such as Journal of Business Research, Transylvanian Review of Administrative Science, Health Marketing Quarterly, Innovar Journal of Administrative and Social Sciences and Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administracin.

237

Introduction

Independent of the industry in which the company performs, internet sites have been transformed into an efficient and low-cost means of providing information to current clients, potential clients, employees, stockholders, and suppliers (Yang et al., 2005). Information systems are at the forefront of company relations with customers and should, therefore, be studied as a robust resource for identifying customers perspectives regarding service quality and other characteristics of the product. In the particular case of online banking, the objective of its websites is to create a working environment where users can easily and quickly navigate to find the information they require for performing financial transactions (Alds-Manzano et al., 2009, p.673). Among other things, the internet has allowed banks to cut costs and delegate tasks to consumers (Jayawardhena and Foley, 2000), develop joint businesses and widen their client base (Sohail and Shaikh, 2008), offer more competitive prices (Jayawardhena, 2004), massively personalise their services (Dannenberg and Kellner, 1998), and acquire useful knowledge of client activities (Yiu et al., 2007). As this new stage of service evolves, banks will be able to take advantage of emerging opportunities, so long as website is carefully monitored so that they are always available, work correctly, seem relevant, and offer the necessary guarantees so that clients use such services in a comfortable, straightforward, and secure way. On the contrary, if, for example, transactions are executed with errors, in an untimely manner, or there is no access to needed information, services offered through the internet may be evaluated negatively (Parasuraman et al., 2005), in turn damaging the credibility of the system and the global image of the bank.

238

E. Torres-Moraga, A.Z. Vsquez-Parraga and C. Barra

In order to achieve an effective handling of the website, it is necessary for internet banks to understand in detail how users perceive and evaluate services offered through the internet (Parasuraman et al., 2005). It is here that service quality assessment becomes a fundamental factor. The literature shows that service quality has acquired a leading role in this industry because it acts in part as an important source of differentiation between competitors (Ranganathan and Ganapathy, 2002), and also as an essential element for attracting and retaining clients (Liao and Cheung, 2002). Yet, viability of service quality as a significant variable in internet banking is only now emerging in developing countries, whereas it is almost taken for granted in developed countries. Recognition of the potential impact of service quality is growing in Chile, but it is not yet a differentiator in competition, as it is in Europe or the USA. Latin America represents approximately 10% of the worlds total number of internet users with close to 175 million users and a penetration index averaging 22% among Latin American countries (Internet World Stats, 2009). Within the region, Chile stands out as one of the countries with the greatest increase in internet use. The number of internet users in Chile grew by 376% between 2000 and 2009, such growth having the highest penetration in Latin America at 50.4%, over a total population that approaches 16.5 million (Internet World Stats, 2009). In the particular case of banking, the number of connected clients that use banking services on the internet approaches 14% of the countrys total population, with an average annual growth rate of 28.2% between 2000 and 2008 (20.9% between 2006 and 2008). In the same period, the growth of banking transactions through the internet has grown to an average annual rate of 47.0% (27.8% between 2006 and 2008), according to Chiles national banking regulatory agency, Superintendencia de Bancos e Instituciones Financieras de Chile (SBIF, 2009). All of these conditions point to Chile as an appropriate research site for analysing the quality of internet financial services in a Latin American environment. Thus, two key reasons emerge as arguments for measuring service quality and for developing relevant measures specific to Chilean banks that have moved into the internet banking arena. First, Chilean banks have begun to acknowledge the importance of service quality as a condition for achieving higher performance in internet services. Second, while internet banking has grown significantly in Chile, currently no corresponding means exist for measuring and assessing service quality in this increasingly important area of banking. Service standards need to be developed for internet banking so that practice in the area can be significantly improved. Consequently, the objective of this study is to propose and test a scale of service quality for internet banking. The scale is fully assessed in terms of reliability, validity, and dimensionality so as to facilitate its implementation by banks interested in evaluating the performance of their internet banking platforms. This study is contextualised within the framework of an emerging economy context such as Chiles. The following section presents a review of service quality literature in traditional as well as online environments, specifically in the realm of internet banking. Next, the relevant variables to be considered in the study are selected using The Critical Incident Technique (CIT), and a series of procedures are used in order to achieve a scale with content validity. After that, a series of analyses are carried out, including structural equations to guarantee that the assessment scale has a high degree of reliability, validity and dimensionality. Finally, conclusions and a discussion of the results are presented.

How to measure service quality in internet banking

239

Literature review

Authors have approached service quality in online information systems first and, then, focused on service quality in internet banking. Consequently, we will first review the literature on service quality that is applied to online information systems. We present a brief historical account of how did instruments devoted to measure service quality in online information systems emerge and how did they give birth to the new measures such as the ones this study adopt. The growing proliferation and use of the internet as a medium to provide and complement services offered by companies has generated new forms of consumer interaction for which the traditional concept of service quality is not totally applicable. These changes have transformed the process that consumers use to evaluate company performance (Parasuraman et al., 2005) and have, thus, determined how websites are developed and presented by the offering companies. With each company website, customers are confronted with a different array of service options. Those companies that value service quality are likely to have noticeable or even highlighted customer response feedback options on their websites.

2.1 Service quality in online information systems

Diverse studies have focused exclusively on service quality for online information environments. One of the first instruments created to assess service quality in information systems was the one developed by Kettinger and Lee (1997). This scale was called IS SERVQUAL and was developed from an adaptation of works previously completed for application in traditional services. The problem with this scale is that it did not have applicability for internet-based services which at that time were only minimally developed at a global level. An attempt to conceptualise and assess online service quality was later made by Liu and Arnett (2000). These researchers developed a survey that includes the assessment of five key dimensions: design, playfulness, quality of information, security, and service. Another scale created to assess service quality in an electronic business context was the SiteQual scale, composed of nine items grouped in four dimensions, including aesthetic design, ease of use, processing speed, and security (Yoo and Donthu, 2001). However, one of the major drawbacks of this instrument is that it does not totally consider the perceptions of the consumer in regard to buying process (Sohail and Shaikh, 2008). Another scale, proposed by Van Riel et al. (2001), is composed of three major factors: core services, supporting services, and user interface. This scales application is centred on the webs medical information portals. The work of Loiacono et al. (2002), noted for the WebQual scale composed of 12 dimensions, is also relevant in this review. This scale focused on the technical quality of websites while not considering some factors that are inherent in the experience of web page users. Another relevant scale is WEBQUAL 4.0 (Barnes and Vidgen, 2002), composed of five dimensions: design, empathy, information quality, trust, and usability. Other developments centred on the creation of a scale to specifically assess service quality in online shopping sites. Among them is the work of Madu and Madu (2002) with an assessment tool that includes 15 categories. There is also the E-SERVQUAL scale developed by Zeithaml et al. (2002) composed of 11 dimensions. Furthermore, the

240

E. Torres-Moraga, A.Z. Vsquez-Parraga and C. Barra

eTailQ scale can also be mentioned (Wolfinbarger and Gilly, 2003). Through a focus group, the most important service quality dimensions were put together, taking into consideration the online context as much as the offline one. The result was a 14-item instrument grouped in four dimensions: customer service, design, privacy/security, and reliability/fulfilment. The most recent studies include the contribution of Yang et al. (2005). Through a study of the quality perceived in different web portals, five dimensions were defined: accessibility, adequacy of information, content usefulness, interaction, and usability. The E-S-Qual scale developed by Parasuraman et al. (2005) is composed of 22 items (just like its original SERVQUAL scale) grouped in four dimensions: efficiency, fulfilment, privacy, and system availability. This scale was complemented by a second scale, the E-RecS-Qual, focused on measuring service recovery situations and composed of three dimensions: compensation, contact, and responsiveness. Several measures and measurement systems have been proposed to evaluate service quality for online offerings. Variations among these systems can be traced to differences among the online information systems to which they have been applied and to differences in the ways that competing companies have used available measurement systems as differentiating tools. In addition, some authors have proposed the use of levels of analysis (theory, data collection, statistical analysis) to better assess service quality (e.g. Miller et al., 2008) not only for individuals but also for aggregations (Chan, 1998). In Table 1, a summary of the dimensions considered by the principal studies conducted on online environments can be observed.

Table 1 Authors Kettinger and Lee (1997) Liu and Arnett (2000) van Riel et al. (2001) Summary of dimensions considered by diverse online environment studies Name and no. of dimensions IS-SERVQUAL (4 dimensions) (5 dimensions) (3 dimensions) Dimensions Assurance, Empathy, Reliability and Responsiveness Design, Playfulness, Quality of Information, Security, and Service Core Services, Supporting Services, and User Interface Aesthetic Design, Ease of Use, Processing Speed, and Security Context Information Systems Webmasters Medical Web Portal Online Shopping Sites

Yoo and Donthu Site-Qual (2001) (4 dimensions) Loiacono et al. (2002) WebQual (12 dimensions)

e-Commerce Business Process, Design Appeal, Fit to Task, Flow, Innovativeness, Integrated Communication, Interactivity, Intuitiveness, Response Time, Substitutability, Trust, and Visual Appeal Design, Empathy, Information Quality, Trust, and Usability Aesthetics, Assurance, Differentiation and Customisation, Empathy, Features, Performance, Reliability, Reputation, Responsiveness, Security and Integrity, Serviceability, Storage Capacity, Structure, Trust, and Web Policies Online Book Stores Online Shopping Sites

Barnes and Vidgen (2002)

WebQual 4.0 (5 dimensions)

Madu and Madu (15 dimensions) (2002)

How to measure service quality in internet banking

Table 1 Authors Zeithaml et al. (2002)

241

Summary of dimensions considered by diverse online environment studies (continued) Name and no. of dimensions eSQ (11 dimensions) Dimensions Access, Aesthetics, Assurance/Trust, Customisation/Personalisation, Ease of Navigation, Efficiency, Flexibility, Price Knowledge, Reliability, Responsibility, and Security Context Online Shopping Sites

Wolfinbarger eTailQ and Gilly (2003) (4 dimensions) Yang et al. (2005) Parasuraman et al. (2005) (5 dimensions)

Customer Service, Design, Online Privacy/Security, and Reliability/Fulfilment Shopping Sites Accessibility, Adequacy of Information, Content Usefulness, Interaction, and Usability (include Security/Privacy) Web Portals

E-S-Qual Efficiency, Fulfilment, Privacy, and (4 dimensions) System Availability/Compensation, and E-RecS-Qual Contact, and Responsiveness (3 dimensions)

Online Shopping Sites

2.2 Internet banking and service quality

Again, we present here a brief historical account of how measures were developed for service quality in internet banking so as to help developing service standards for internet banking. Using a qualitative study carried out by means of the CIT, Jun and Cai (2001) identified three dimensions and 17 sub-dimensions of online banking service quality. This study centred on finding and analysing service encounters that are satisfactory and unsatisfactory for internet bank users, taking into consideration the opinions those US users recorded on a designated web page. It can be pointed out that this research did not result in the development of an instrument that would serve to assess the service quality of internet banking. In a subsequent study, Jayawardhena (2004) presented a scale of five dimensions composed of 21 items. This researcher based the initial stages of his study in the traditional SERVQUAL scale, soon after completing a process of addition of variables and statistical filtering. Bauer et al. (2005) completed an analysis of both internet banking sites and of web portals, attributing to the former the same characteristics as the latter, as such bringing up relevant service quality dimensions for banks on the internet. With this procedure, Bauer et al. (2005) defined six dimensions and an independent assessment scale for each one. Finally, these six dimensions were grouped in three general concepts: additional services, core services, and problem-solving services. On another front is the work completed by Brown and Buys (2005). Basing their study on an instrument previously used in a different cultural context, and with a greatly reduced number of participants, these researchers created an assessment instrument centred on satisfaction which included seven dimensions of service quality. Subsequently, using Exploratory Factor Analysis, they reduced the number of original variables to five, which caused some dimensions to remain constituted by items with little conceptual relation between them.

242

E. Torres-Moraga, A.Z. Vsquez-Parraga and C. Barra

Finally, in a recent study, Sohail and Shaikh (2008), by means of factorial analysis, grouped diverse items used in other studies of online service quality, thereby adapting them to the reality of internet banking. As a result, these dimensions were obtained: efficiency and security, fulfilment, and responsiveness. Table 2 shows a review of the dimensions considered by the main studies carried out in the context of internet banking.

Table 2 Authors Jun and Cai (2001) Summary of contexts and dimensions considered by diverse internet banking studies No. of dimensions/ characteristics (3 dimensions) Website Comments Content Analysis Dimensions Banking Service Products Quality (Product Variety), Customer Service Quality (Responsiveness, Reliability and Access), and Online Systems Quality (Ease of Use and Accuracy) Access, Attention, Credibility, Trust, and Web Interface Additional Services (Cross-Buying Services Quality and Added Values), Core Services (Security and Trust, and Basic Services Quality), and Problem-Solving Services (Transaction Support and Responsiveness) Customer Support, Ease of Use, Information Content and Innovation, Security, and Transactions and Payment Efficiency and Security, Fulfilment, and Responsiveness Context USA

Jayawardhena (2004) Bauer et al. (2005)

(5 dimensions) Post-Graduate Students Convenience (6 dimensions) Internet Users SelfSelection

UK

Germany

Brown and Buys (2005)

(5 dimensions) e-Banking Users SelfSelection

South Africa

Sohail and Shaikh (2008)

(3 dimensions) e-Banking Users Snow-Ball

Middle East (Saudi Arabia)

The identified studies underscore the importance of cultural context in the development of evaluative instruments for online services, in particular e-banking services. Appropriately, this study is anchored in an emerging context in Latin America where online systems and e-banking, in particular, are growing at a breakneck pace. Latin American consumers may share characteristics with consumers from other geographic and demographic contexts, but they also manifest particular requirements exclusive to Latin American consumers of online services if those services are to be considered satisfactory. Consequently, performance measures, service quality measures in particular, must reflect such needs and conditions if business efforts in satisfying customers are to be deemed successful.

How to measure service quality in internet banking

243

The methodology presented in the following section highlights information and communication needs of internet banking customers. However, particular attention is devoted to cultural factors that influence customers judgement of the effectiveness of the information and communication systems utilised by internet banking websites.

Methodology

As noted in the prior section, varying service quality scales exist for different electronic business contexts, but specific developments for internet banking are quite rare. In order to put together a service quality scale with a sufficient degree of content validity, and at the same time tailored to the context of the study, a series of analyses which can be summed up in two stages were carried out.

3.1 Development of the measurement scale

In the first of these stages, the relevant service quality dimensions that would become part of the measurement scale were identified. To do this, a study using the CIT was used. A series of thorough interviews were conducted in which the interviewees were asked to describe different situations in which an internet bank had offered them good service or bad service. This study used an adaptation of the requirements suggested by Bitner et al. (1990). In order for this methodology to be used, the incidents had to satisfy four conditions: 1 2 3 4 involve interaction between the bank web and the client be very satisfactory or unsatisfactory from the point of view of the consumer be a discrete episode have enough detail so as to be visualised by the interviewer.

The research sample consisted of 124 individuals selected by convenience from a nonprobability sample as interview subjects. Through these interviews, 207 valid critical incidents were obtained. The interviewees were required to have carried out at least three monthly financial operations through their bank web page within the past three months. In the interview, a semi-structured guideline put together from what was proposed in the study by Bitner et al. (1990) was used. This was pre-tested in a group of 15 people with the goal of preventing future problems in its application and in the subsequent analysis of the facts. Subsequently, the studys preliminary results were analysed in conjunction with different experts and bank managers who operated through the internet. Through these procedures, the following six dimensions for internet banking service quality were obtained: response capacity, privacy/security, accessibility/availability, usefulness, exactitude, quality of the products, and services (see Appendix A). Each one of these dimensions is defined next: Accessibility/Availability (AA): Availability and correct functioning of website. Accuracy (AC): Content, transactions, and interface through the website being free of error. Products/Services Quality (PQ): Characteristics and variety of products and services offered by the bank through the internet.

244

E. Torres-Moraga, A.Z. Vsquez-Parraga and C. Barra Responsiveness (RE): Effective handling of users problems and the banks response capacity through the internet. Security/Privacy (SP): The users perception of the protection of his or her personal information and of the structural security of the website. Usability (US): Perception of the effort that must be made to navigate through the banks website.

In the final stage, the scale was put together and then it was sifted. The work of previous researchers served as the basis for the development of the scale: in the case of the accessibility/availability dimension, the works of Yang et al. (2005) and Parasuraman et al. (2005); for the accuracy dimension, studies by Parasuraman et al. (2005) and Brown and Buys (2005); for responsiveness, Devaraj et al. (2002), Kim et al. (2004), and Parasuraman et al. (2005); for the security/privacy dimension, the works of McKnight et al. (2002), Wolfinbarger and Gilly (2003), and Kim and Prabhakar (2004); for products/services quality, Szymanski and Hise (2000), and Gounaris et al. (2003); and finally, for usability, the works of Roy et al. (2001), Kim et al. (2004), and Flavin et al. (2006). Subsequently, these scales were sifted taking into consideration exhaustive analysis recommended by De Wulf and Odekerken-Schrder (2003). Specifically, a series of focus groups composed of people who were habitually making bank transactions through the internet were brought together and interviewed. Interviews with management from diverse banks also took place. This analysis permitted those indicators that more adequately reflect service quality in a study context to be added up. It also permitted conflictive or redundant indicators to be readapted and/or eliminated. In particular, a modification of the method by Zaichkowsky (1985) was used for this analysis. Each expert had to qualify each item with respect to its dimension. Three alternatives were considered: clearly representative, somewhat representative, or not at all representative. Finally, those items in which a high level of consensus existed were retained. With these analyses, the scale with which the questionnaire was put together was obtained. The items were drafted as declarative statements (no questions were used as items), and worded carefully to ensure all items could be understood and responded to by all interviews. The response instrument was a seven-point Likert scale. Finally, with this initial questionnaire, a quantitative pre-test was conducted on a random sample of 45 clients from different internet banks. Subsequently, an exploratory factorial analysis was carried out with the data, and Cronbachs alpha was calculated for each resulting dimension. With this previous analysis, the existence of each resulting dimension was confirmed (see Appendix A).

3.2 Sample and application of questionnaire

Once completed, the questionnaire was administered to consumers who used their bank services through the web. Personal interviews were conducted by telephone during the months of November and December 2007 in the city of Santiago, Chile. Specialised software called CATI that allows both contact telephone numbers and the order of Likert questions for interviewees to be selected at random was used. The advantage of using the telephone format, in the context of Chile, rests in the fact that it reaches a higher percentage of responses representing the targeted population.

How to measure service quality in internet banking

245

From a pool of 53,819 random calls made, a sample of 640 valid cases was generated. The sample size represent more than double the sample, size needed (300) to test the proposed scales. Early returns were compared to late returns for the purpose of addressing non-response bias for the study. Non-significant differences were observed in the comparison regarding both the demographic characteristics of the sample and the scale averages. Lost cases relate to rejections (10,740), e-banking non-users, truncated conversations, and inactive phone numbers. Atypical cases, repeated answers, and incomplete questionnaires were controlled. Table 3 shows the sample profile in detail.

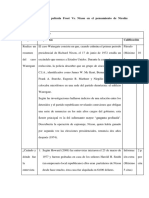

Table 3 Gender Man Woman Age Between 18 and 24 years Between 25 and 34 years Between 35 and 44 years Between 45 and 54 years 55 years and above No response Level of Education Primary and Secondary Education Superior Technical Education University Post-Graduate No response Annual Family Income Less than US$6600 Between US$6601 and US$13,001 Between US$13,001 and US$20,000 Between US$20,001 and US$41,000 More than US$41,000 No response For how long have you been carrying out internet banking operations with your bank? 4 years and less More than 4 years From where do you carry out internet banking operations with your bank? Home Place of Work Public internet places Other places (university, a relatives home) 72.3 46.3 5.9 3.2 55.8 44.2 2.6 12.8 22.5 32.9 19.0 10.2 10.8 19.5 63.3 5.8 0.6 19.2 32.3 21.3 14.0 11.8 1.4 49.8 50.2 Profile of the sample (%)

246

E. Torres-Moraga, A.Z. Vsquez-Parraga and C. Barra

3.3 Analysis of service quality scale

In this section, the proposed service quality scale is analysed to see if it has a sufficient degree of dimensionality, reliability, and validity.

3.3.1 Dimensionality analysis

This analysis consists in determining whether each of the six sub-scales or dimensions that compose the service quality construct show a sufficient degree of unidimensionality. To carry out this analysis, exploratory factorial analysis of principal components with varimax rotation was employed. The extraction of the factor was based on the existence of independent values greater than 1. Furthermore, it was required that the explained variance be significant and that each of the factorial loadings be greater than 0.5 (Hair et al., 2005). This analysis revealed that each of the six scales was represented in only one factor, thereby showing the completion of the unidimensionality condition (see Table 4).

Table 4 Sub-scale Accessibility/Availability (AA) Accuracy (AC) Products/Services Quality (PQ) Responsiveness (RE) Security/Privacy (SP) Usability (US) Exploratory factor analysis of service quality sub-scales Variable aa1 aa2 aa3 ac1 ac2 ac3 pq1 pq2 pq3 re1 re2 re3 sp1 sp2 sp3 us1 us2 us3 Factor loading 0.838 0.846 0.678 0.829 0.721 0.869 0.860 0.835 0.725 0.856 0.900 0.883 0.844 0.875 0.839 0.901 0.921 0.874 Variance explained (%) Eigenvalue 62.54 1.88

65.37

1.96

65.34

1.96

77.44

2.32

72.76

2.18

80.86

2.43

3.3.2 Confirmatory analysis of dimensionality and reliability 3.3.2.1 Confirmatory factorial analysis

Subsequently, confirmatory factorial analysis was carried out through the structural equations method. To conduct this analysis, EQS 6.1, statistical software, was used. A development model strategy was applied taking into consideration the different subscales or latent variables (Hair et al., 2005). That is to say, the necessity of eliminating indicators or variables that could impede reaching a good adjustment of the model was analysed. The three criterions proposed by Jreskog and Srbom (1993) were considered.

How to measure service quality in internet banking

247

The first criterion of weak convergence would eliminate indicators that did not have a significant factorial regression coefficient (Students t test > 2.58, p = 0.01). A second criterion of strong convergence would eliminate those indicators that were not substantial, that is, those whose standardised coefficient () is less than 0.5 (Hildebrant, 1987). Lastly, Jreskog and Srbom (1993) also suggest eliminating the indicators that contribute least to the explanation of the model, considering the cut-off point as R2 < 0.3. Taking into consideration the three previous criterions, it was not necessary to eliminate indicators. Thus, the adjustments of the model were quite satisfactory: 2 (df) 307.68 (120); IFI 0.97; CFI 0.97; TLI 0.96; RMSEA 0.05; normed 2 2.56.

Figure 1 Confirmatory factor analysis

R2: 0.51 R2: 0.71 R2: 0.72

re1

0.72*

re2

0.84*

re3

0.85*

0.83* R2: 0.58 R2: 0.63 R2: 0.60

RE

0.90* 0.72*

sp1 sp2 sp3

0.76* 0.79* 0.77* 0.65* 0.82* 0.64* 0.84* 0.76* 0.78* 0.81* 0.80*

aa1 aa2 aa3

R2: 0.51 R2: 0.69 R2: 0.31

SP

0.74* 0.87*

AA

0.83* 0.50*

R2: 0.72 R2: 0.82 R2: 0.64

us1 us2 us3

0.85* 0.90* 0.80*

0.79*

ac1 ac2 ac3

R2: 0.62 R2: 0.32 R2: 0.55

US

0.72*

AC

0.51* 0.74*

0.61*

PQ

0.79*

0.79*

0.76*

0.58*

pq1

R2: 0.63

pq2

R2: 0.58

pq3

R2: 0.38

Note:

*Significant at p < 0.01.

3.3.2.2 Rival model strategy

With the objective of confirming that the service quality construct is multidimensional, a Rival Model Strategy was developed (Hair et al., 2005). Thus it was determined that service quality in the context of internet banking is composed of the following dimensions: accessibility/availability, accuracy, products/services quality, responsiveness, security/privacy, and usability. This analysis consists in comparing two alternative

248

E. Torres-Moraga, A.Z. Vsquez-Parraga and C. Barra

models, a first-order model with one of second-order (Steenkamp and Van Trijp, 1991). In the first-order model, all the indicators or items of the construct load on only one factor. On the other hand, with the second order, the construct is represented by the six dimensions. The results demonstrated that the second-order model showed better adjustment levels with which it was possible to confirm the multidimensionality of the service quality (Table 5).

Table 5 Multidimensional analysis of construct (service quality) Optimum value 2 (df) NCP SNCP GFI RMSR RMSEA IFI CFI AGFI NFI NNFI AIC Normed

2

First-order model 825.759 (135)

Second-order model 374.811 (129) 245.811 0.384 0.938 0.068 0.055 0.960 0.960 0.917 0.940 0.952 116.811 2.906

Absolute adjustment measures Minimum Minimum Near 1 Minimum < 0.08 Near 1 Near 1 Near 1 Near 1 Near 1 Minimum [1 ; 5] 690.759 1.079 0.819 0.089 0.104 0.850 0.849 0.771 0.826 0.829 555.759 6.116

Incremental adjustment measures

Parsimony adjustment measures

3.3.2.3 Reliability analysis

In this stage, the degree of reliability of the service quality construct should be verified. To recognise the reliability of each of the measurement sub-scales that compose service quality, two analyses were carried out: Cronbachs alpha analysis and the Composite Reliability Coefficient (CRC) (Jreskog, 1971). The purpose is to determine whether similar results can be obtained with these sub-scales when they are applied in other occasions to a same group of individuals. This last index has the advantage, in contrast to the first, of not being influenced by the number of indicators included in the analysis. The same as Cronbachs alpha, in accordance with this index, a scale is considered reliable when it shows values superior or equal to 0.7 (Hair et al., 2005). Based on the combined analysis of both criterions, each one of the scales can be considered reliable.

3.3.3 Validity analysis

The schema put forth by Nunnally (1978) was followed to prove the validity of the construct. According to Nunnally, for validity to exist, it should be proven that the proposed scale has content validity, construct validity, and validity with relation to a criterion.

How to measure service quality in internet banking

249

With respect to content validity, it should be kept in mind that it is for the most part guaranteed due to the fact that the scales for measuring service quality have been designed from an exhaustive previous qualitative analysis, a detailed analysis of the literature, and subsequently subjected to the judgement and discussion of different experts. Construct validity can be guaranteed through convergent validity and discriminant validity. Convergent validity was confirmed (see Figure 1) observing that in all the scales the standardised coefficients that the confirmatory model showed were statistically significant at 0.01 and greater than 0.50 (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988; Bagozzi and Yi, 1988). Discriminant validity was confirmed through two procedures: the chi-square difference test and confidence interval test (Bagozzi, 1981; Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). The first of these consists of comparing the chi-square of the resulting model of factorial analysis with the different alternative models in which two of their dimensions show a perfect correlation. Each one of the 15 alternative models compared with the model resulting from confirmatory factorial analysis are constituted by the same dimensions that this resulting model contains, but differing in that two of these dimensions are fixed with a perfect correlation. Discriminant validity shall exist when the differences in the chi-square resulting from this comparison are significantly different. As can be observed in Table 6, in all studied cases, the differences between the theoretical model resulting from confirmatory factorial analysis and the different alternative models, turned out to be highly significant. In the case of the interval confidence test, discriminant validity is seen as existing between two latent variables when the confidence intervals resulting from estimating the correlation between both latent variables does not include the value 1 as can be observed in Table 6.

Table 6 Discriminant validity and reliability of sub-scales Discriminant validity Test 2 Construct pairs AA-AC AA-PQ AA-RE AA-SP AA-US AC-PQ AC-RE AC-SP AC-US PQ-RE PQ-SP PQ-US RE-SP RE-US SP-US Confidence intervals 0.73; 0.86 0.71; 0.85 0.84; 0.93 0.69; 0.83 0.73; 0.85 0.64; 0.77 0.78; 0.89 0.77; 0.89 0.55; 0.70 0.83; 0.93 0.73; 0.86 0.73; 0.87 0.79; 0.89 0.59; 0.72 0.60; 0.74 Reliability Construct AA AC PQ RE SP US CRC 0.69 0.70 0.71 0.76 0.72 0.80 Cronbachs alpha 0.71 0.72 0.73 0.85 0.81 0.88

Differences 47.68 45.23 24.69 71.46 71.19 45.23 48.38 43.29 123.75 29.49 58.32 165.88 60.35 285.76 195.22

df; p-value df = 1; p < 0.01 df = 1; p < 0.01 df = 1; p < 0.01 df = 1; p < 0.01 df = 1; p < 0.01 df = 1; p < 0.01 df = 1; p < 0.01 df = 1; p < 0.01 df = 1; p < 0.01 df = 1; p < 0.01 df = 1; p < 0.01 df = 1; p < 0.01 df = 1; p < 0.01 df = 1; p < 0.01 df = 1; p < 0.01

250

E. Torres-Moraga, A.Z. Vsquez-Parraga and C. Barra

Therefore, with all of these antecedents, it can be affirmed that in the proposed model, convergent and discriminant validity exists between the latent variables that compose it. Once the analyses to determine the internal validity through content and construct validity have been completed, it is appropriate to apply validity analysis outside of the model by means of validity analysis related to a criterion. The main purpose of this analysis is to determine with what efficacy the proposed scale allows the service quality concept to be related with that variable criterion that the theory shows it should be related to. From the point of view of the moment in time in which the analysed variables are obtained, two types of validity analysis can be achieved with relation to a criterion: concurrent validity and predictive validity. Since the facts have been obtained in the same moment in time, predictive validity cannot be done and for this reason concurrent validity was carried out. To complete this type of validity, a causal relation suggested in the literature about electronic commerce was proposed, expressing that service quality could have direct influence on the satisfaction of consumers (Szymanski and Hise, 2000; Van Riel et al., 2004). This causal model was contrasted by means of the structural equations method. For this analysis, the proposed service quality construct was used as well as a scale with sufficient content validity, which was constructed to assess the satisfaction of internet banking clients. The results show that an evident positive cause-and-effect relation exists between the service quality of an internet bank and the satisfaction that clients have with that institution. (standard coefficient 0.85; t-value 18.06). Furthermore, the models explicative capacity is considerably elevated in obtaining a value of R2 = 0.73. This allows us to deduce that the proposed service quality construct of an internet bank shows an adequate concurrent validity which backs up the validity criterion of this measurement variable. The models adjustments turned out to be satisfactory with these values: 2 (df) 514.09 (182); IFI 0.95; CFI 0.95; RMSEA 0.05; normed 2 2.82. Finally, considering all the analyses carried out in this study, it can be concluded that the scale finally proposed to measure service quality of internet banks, from the consumers perspective, shows a sufficient degree of reliability, validity and dimensionality (see Appendix A).

Conclusion and discussion of the results

The purpose of this study was to propose and test a scale of service quality for internet banking as defined by users functioning in the context of an emerging economy. Current literature in this area served as scaffolding for identifying six key dimensions of service quality offered by internet banking: accessibility/availability, accuracy, products/services quality, responsiveness, security/privacy, and usability. The proposed scale offers an assessment instrument for banks to evaluate their performance and effectiveness in online transactions. The development of the proposed scale has been based on a meticulous qualitative analysis which included a profound content validity analysis. Furthermore, the scale was verified through exhaustive psychometric analysis of the facts with which its reliability and validity (convergent, discriminant, and external based on one criterion) was proven. It also included statistical tools used to prove the subjacent structure discovered in previous steps, thereby verifying the unidimensionality, reliability, and validity of each of the service quality construct components. Dimensions not interrelated by the same concept, were not presented.

How to measure service quality in internet banking

251

As a result, this study proposes an easy to apply, and not too extensive instrument, that will allow internet banks to carry out periodic assessment of consumer satisfaction with the banks websites and to gauge changes in consumer perceptions of banking services . The results of this study could influence future developments in e-banking in Latin America, in particular Chile. Chile has been a pioneer in internet banking in the region (internet penetration in Chile is 20% higher than the average for the region). In addition, e-banking in Chile has already reached 83% of overall banking with a rate of growth close to 40% during the last five years. However, no assessment measures are currently in place to conduct appropriate performance evaluations. Given the increase in demand for e-banking services in Latin America, developing and implementing performance measures is appropriate and timely. E-banking requires evaluative instruments different from the traditional ones used for non-internet banking. This study has moved beyond existing banking performance measures to suggest that new, research-based protocols are necessary as banks move into increased levels of e-banking. Sustained and continued growth in internet banking must be based on assessment of a banks overall performance.

Limitations of the study and direction for future research

The context in which the study was performed, Chile, and the method used for collecting data, telephone survey, may have limited the generalisability and validity of the research. Further tests in different contexts, such as non-Latin contexts, and using different testing methods, such as internet survey or mail survey, will undoubtedly enhance the contribution of this type of research to a better understanding of service quality in internet banking. In addition, a practical continuation of the research is mapping the scale results so as to offer a useful tool of application for banks and other users.

Implications and applications to the administration and management of services and standards to internet banking

In practical terms, the findings of this study allow bank executives and management to have a tool with which to handle relevant service quality factors. Particularly, in accordance with the results of this study, bank managing should focus on guaranteeing that their website functions correctly, that it be available, and that it be usable when users require it. Additionally, cautionary mechanisms to help clients deal with disruptions in these key areas should be established. Once available, bank services should function free of error, correctly, exactly, and promptly showing clients financial information as well as the results of transactions, thereby avoiding a misunderstanding of procedures. Products and services offered through the web should be relevant for the client, consistent with his or her needs, varied, and capable of being a complete and non-partial substitute of certain traditional banking services. In case of problems, the bank should count on established procedures for their solution, whether through a virtual route, or when necessary, by complementing the response with human action. Furthermore, it should count on support systems to satisfy customer service requirements.

252

E. Torres-Moraga, A.Z. Vsquez-Parraga and C. Barra

In other aspects, security and privacy should be guaranteed, whether with personal information the bank possesses or with transactions that take place. The bank should make known the security policies affecting financial operations carried out through the internet, explaining the implications that an unexpected or sudden failure could have, as well as systems of back-up, confirmation, and transaction authenticity of their clients. Lastly, the physical and logical structure of the website should be easy to understand and to use, adapting itself to the diverse needs of different users which may or may not have significant gaps in their handling of technology. Finally, banks should keep in mind that the quality management of their internet operations takes into account a synergetic handling of all the composing dimensions of service quality, as well as an individual handling of each of the dimensions so as to adjust those variables that could possibly affect the general perception of internet banking service quality. Thus, the advantages of effective administration, and therefore, of favourable perception of service quality, can generate competitive advantages.

Acknowledgements

This research was generated as part of a project titled Development of a trust model in the context of internet banking under FONDECYT, Regular No. 1070892, funded by the National Commission of Scientific Research and Technology, CONICYT (Chile).

References

Alds-Manzano, J., Lassala-Navarr, C., Ruiz-Maf, C. and Sanz-Blas, S. (2009) Key drivers of internet banking service use, Online Information Review, Vol. 33, No. 4, pp.672695. Anderson, J.C. and Gerbing, D.W. (1988) Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 103, No. 3, pp.411423. Bagozzi, R.P. (1981) Evaluating structural equations models with unobservable variables and measurement error: a comment, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp.375381. Bagozzi, R.P. and Yi, Y. (1988) On the evaluation of structural equation models, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp.7495. Barnes, S.J. and Vidgen, R.T. (2002) An integrative approach to the assessment of e-commerce quality, Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp.114127. Bauer, H.H., Hammerschmidt, M. and Falk, T. (2005) Measuring the quality of e-banking portals, International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp.153175. Bitner, M.J., Booms, B.H. and Tetreault, M.S. (1990) The service encounter: diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 54, No. 1, pp.7184. Brown, I.J. and Buys, M. (2005) Customer satisfaction with internet banking web sites: an empirical test and validation of a measuring instrument, South African Computer Journal, Vol. 35, pp.2937. Chan, D. (1998) Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: a typology of composition models, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 83, No. 2, pp.234246. Dannenberg, M. and Kellner, D. (1998) The bank of tomorrow with todays technology, International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp.9097. de Wulf, K. and Odekerken-Schrder, G. (2003) Assessing the impact of a retailers relationship efforts on consumer attitudes and behavior, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp.95108.

How to measure service quality in internet banking

253

Devaraj, S., Fan, M. and Kohli, R. (2002) Antecedents of B2C channel satisfaction and preference: validating e-commerce metrics, Information Systems Research, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp.316333. Flavin, C., Guinalu, M. and Gurrea, R. (2006) The influence of familiarity and usability on loyalty to online journalistic services: the role of user experience, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 13, No. 5, pp.363375. Gounaris, S.P., Stathakopoulos, V. and Athanassopoulos, A.D. (2003) Antecedent to perceived service quality: an exploratory study in the banking industry, International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp.168190. Hair Jr., J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B., Anderson, R.E. and Tatham, R.L. (2005) Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed., Prentice-Hall International, London. Hildebrant, L. (1987) Consumer retail satisfaction in rural areas: a reanalysis of survey data, Journal of Economic Psychology, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp.1942. Internet World Stats (2009) Available online at: http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm (accessed on 25 September 2009). Jayawardhena, C. (2004) Measurement of service quality in internet banking: the development of an instrument, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 20, pp.185207. Jayawardhena, C. and Foley, P. (2000) Changes in banking sector the case of internet banking in the UK, Journal of Internet Research: Networking and Policy, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp.1930. Jreskog, K.G. (1971) Statistical analysis of sets of co-generic test, Psycometrika, Vol. 36, pp.109133. Jreskog, K.G. and Srbom, D. (1993) New Feature in LISREL 8, Scientific Software, Chicago, IL. Jun, M. and Cai, S. (2001) The key determinants of internet banking service quality: a content analysis, International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 19, No. 7, pp.276291. Kettinger, W.J. and Lee, C.C. (1997) Pragmatic perspective on the measurement of information systems service quality, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp.223240. Kim, K.K. and Prabhakar, B. (2004) Initial trust and the adoption of B2C e-commerce: the case of internet banking, Database for Advances in Information Systems, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp.5065. Kim, H., Xu, Y. and Koh, J. (2004) A comparison of online trust building between potential customers and repeat customers, Journal of Association for Information Systems, Vol. 5, No. 10, pp.392420. Liao, Z. and Cheung, M.T. (2002) Internet-based e-banking and consumer attitudes: an empirical study, Information & Management, Vol. 39, No. 4, pp.283295. Liu, C. and Arnett, K.P. (2000) Exploring the factor associated with web site success in the context of electronic commerce, Information & Management, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp.2334. Loiacono, E.T., Watson, R.T. and Goodhue, D.L. (2002) WebQual: a measure of website quality, in Evans, K. and Scheer, L. (Eds): Marketing Educators Conference: Marketing Theory and Applications, Vol. 13, pp.432437. Madu, C.N. and Madu, A.A. (2002) Dimensions of e-quality, International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp.246258. McKnight, D.H., Choudhury, V. and Kacmar, C. (2002) Developing and validating trust measures for e-commerce: an integrative typology, Information Systems Research, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp.334359. Miller, R., Hardgrave, B. and Jones, T. (2008) Levels of analysis issues relevant in the assessment of information systems service quality, International Journal of Services and Standards, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp.115. Nunnally, J.C. (1978) Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. and Malhotra, A. (2005) E-S-Qual: a multiple-item scales for assessing electronic service quality, Journal of Service Research, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp.213233. Ranganathan, C. and Ganapathy, S. (2002) Key dimensions of B2C web sites, Information & Management, Vol. 39, No. 6, pp.457465.

254

E. Torres-Moraga, A.Z. Vsquez-Parraga and C. Barra

Roy, M.C., Dewit, O. and Aubert, B.A. (2001) The impact of interface usability on trust in web retailers, Internet Research, Vol. 11, No. 5, pp.388398. SBIF (2009) Superintendencia de Bancos e Instituciones Financieras. Available online at: http://www.sbif.cl/sbifweb/servlet/InfoFinanciera?indice=4.1&idCategoria=564&tipocont=18 11 (accessed on 25 September 2009). Sohail, M.S. and Shaikh, N.M. (2008) Internet banking and quality of service: perspective from a developing nation in the Middle East, Online Information Review, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp.5872. Steenkamp, J.B.E. and van Trijp, H.C.M. (1991) The use of LISREL in validating marketing constructs, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp.283299. Szymanski, D.M. and Hise, R.T. (2000) e-Satisfaction: an initial examination, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 76, No. 3, pp.309322. van Riel, A.C.R., Lemmink, J., Streukens, S. and Liljander, V. (2004) Boost customer loyalty with online support: the case of mobile telecoms providers, International Journal of Internet Marketing and Advertising, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp.423. van Riel, A.C.R., Liljander, V. and Jurrins, P. (2001) Exploring customer evaluations of e-services: a portal site, International Journal of Service Industry Management, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp.359377. Wolfinbarger, M. and Gilly, M.C. (2003) eTailQ: dimensionalizing, measuring and predicting etail quality, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 79, No. 3, pp.183198. Yang, Z., Cai, S., Zhou, Z. and Zhou, N. (2005) Development and validation of an instrument to measure user perceived service quality of information presenting web portals, Information & Management, Vol. 42, No. 4, pp.575589. Yiu, C.S., Grant, K. and Edgar, D. (2007) Factor affecting the adoption of internet banking in Hong Kong implications for the banking sector, International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 27, pp.336351. Yoo, B. and Donthu, N. (2001) Developing a scale to measure the perceived service quality of internet shopping sites (Sitequal), Quarterly Journal of Electronic Commerce, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp.3147. Zaichkowsky, J.L. (1985) Measuring the involvement construct, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp.341352. Zeithaml, V.A., Parasuraman, A. and Malhotra, A. (2002) Service quality delivery through web sites: a critical review of extant knowledge, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 30, No. 4, pp.362375.

How to measure service quality in internet banking

255

Appendix A: Proposed scale for measuring service quality of internet banks

Accessibility/Availability My banks website is easily accessible. My banks website is always available for my needs. My banks website always functions correctly. Accuracy My bank puts out exact information through the internet. My bank does not make errors in operations through the website. Registered balances from website bank operations are exact. Products/Services Quality The bank products offered by my bank through the internet satisfy all of my needs. My bank offers products and services through the internet that I consider very necessary. My bank offers a wide gamut of products and services through the internet. Responsiveness When I have a problem through my banks website, I receive a prompt response to meet my needs. My banks website responds to my inquiries or requests in a timely way. My bank worries about responding to my needs. Security/Privacy My banks website is secure. Through its website, my bank has clearly indicated its policies regarding the appropriate use of personal and financial information. I can observe that my banks website has security measures that protect me from vulnerability in the system. Usability My banks website is easy to use. It is easy to find the information I need in my banks website. It is easy to understand the structure and the content of my banks website.

También podría gustarte

- Análisis de Caso de La Película Frost Vs NixonDocumento8 páginasAnálisis de Caso de La Película Frost Vs NixonJavier PinedaAún no hay calificaciones

- Semana4 Equipos de Alto Desempe oDocumento3 páginasSemana4 Equipos de Alto Desempe oAndres Sanchez100% (4)

- Tribunales AdministrativosDocumento5 páginasTribunales AdministrativosJavier Pineda100% (1)

- Análisis de La Película Frost vs. NixonDocumento15 páginasAnálisis de La Película Frost vs. NixonJavier Pineda0% (1)

- Plan de Marketing Via DentDocumento32 páginasPlan de Marketing Via DentJavier PinedaAún no hay calificaciones

- Ensayo Abuso de DerechoDocumento16 páginasEnsayo Abuso de DerechoJavier Pineda0% (2)

- Mazamorra de Quinua12Documento36 páginasMazamorra de Quinua12Javier PinedaAún no hay calificaciones

- Ferreteria Comercial El Economico E.I.R.L.Documento25 páginasFerreteria Comercial El Economico E.I.R.L.Javier PinedaAún no hay calificaciones

- Plan de MarketingDocumento31 páginasPlan de MarketingJavier Pineda0% (1)

- El Callejerito Trabajo FinalDocumento34 páginasEl Callejerito Trabajo FinalJavier PinedaAún no hay calificaciones

- Plan de Mkt. Librería LaykakotaDocumento30 páginasPlan de Mkt. Librería LaykakotaJavier PinedaAún no hay calificaciones

- Exposición MBA Rolan Tello ArbietoDocumento65 páginasExposición MBA Rolan Tello ArbietoJavier PinedaAún no hay calificaciones

- Cronograma Plan de CapacitacionDocumento1 páginaCronograma Plan de CapacitacionCielo AzulAún no hay calificaciones

- Terminos Condiciones AlumnoDocumento2 páginasTerminos Condiciones AlumnoluksjAún no hay calificaciones

- Historia Del ConcretoDocumento3 páginasHistoria Del Concretoteddy0% (1)

- Mundial Fifa Reglamento TorneoDocumento8 páginasMundial Fifa Reglamento TorneoAlejandra MilianAún no hay calificaciones

- Evaluacion 47645e86f67a0ebDocumento12 páginasEvaluacion 47645e86f67a0ebMARA CAROLINA DURN MARTINEZAún no hay calificaciones

- Aprovechamiento de La Energía SolarDocumento9 páginasAprovechamiento de La Energía Solarsebastian morenoAún no hay calificaciones

- Módulo 4 - Bombas AxialesDocumento9 páginasMódulo 4 - Bombas AxialesMassiel Macías MoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- 6 Grado de Primaria-WindowsDocumento130 páginas6 Grado de Primaria-WindowsAnonymous PpDynQAún no hay calificaciones

- DocumentoDocumento2 páginasDocumentolalalelelolo2010Aún no hay calificaciones

- La Autonomía Del Estudiante Digital en Las Ciudades CreativasDocumento3 páginasLa Autonomía Del Estudiante Digital en Las Ciudades CreativasSANDRA MIREYA HERRERA TORRESAún no hay calificaciones

- TAREA N°1 CONTROL DE CALIDAD Luis SalazarDocumento2 páginasTAREA N°1 CONTROL DE CALIDAD Luis SalazarLuis Jose Duarte BohorquezAún no hay calificaciones

- COBIT (Control Objetives For Information and RelatedDocumento34 páginasCOBIT (Control Objetives For Information and RelatedDante GarfioAún no hay calificaciones

- PD - Gtic - U1 - Maria Del Rocio Estrada CampaDocumento10 páginasPD - Gtic - U1 - Maria Del Rocio Estrada CampaA.N. COPIADORASAún no hay calificaciones

- Tabla InversoresDocumento3 páginasTabla InversoresANDREA MORENO ROSASAún no hay calificaciones

- PRC-SST-003 Procedimiento para El Control de Documentos y RegistrosDocumento8 páginasPRC-SST-003 Procedimiento para El Control de Documentos y RegistrosAndrea JimenezAún no hay calificaciones

- Aprendizaje Autorregulado A Través de La Plataforma Virtual MoodleDocumento15 páginasAprendizaje Autorregulado A Través de La Plataforma Virtual MoodleAdriana Milena Rangel Marquez100% (1)

- 4 TaparteDocumento13 páginas4 TaparteGerardo Quiroga (Ger2.4)Aún no hay calificaciones

- Registro de AsistenciaDocumento10 páginasRegistro de Asistenciadanny loaizaAún no hay calificaciones

- Norma Astm d3550 Muestreadorcon Tubo Camisa OriginalDocumento9 páginasNorma Astm d3550 Muestreadorcon Tubo Camisa OriginalAlejandra Coral Lopez DíazAún no hay calificaciones

- Final SimulaciónDocumento8 páginasFinal SimulaciónVaninaAún no hay calificaciones

- Resis Rotoricas PDFDocumento12 páginasResis Rotoricas PDFRoger Alvarez AlvarezAún no hay calificaciones

- Ginansilyo - Freddie Mercury VERSION 1 EspañolDocumento3 páginasGinansilyo - Freddie Mercury VERSION 1 EspañolMaria Adriana PueblaAún no hay calificaciones

- ExtracamaraDocumento25 páginasExtracamaraKremlinPrietoAún no hay calificaciones

- Practica N°6Documento9 páginasPractica N°6BLADIMIR CHARCA MERMAAún no hay calificaciones

- CSi BridgeDocumento8 páginasCSi BridgeesteAún no hay calificaciones

- 001-Guia General Del Constructor Rev.1-SpanishDocumento20 páginas001-Guia General Del Constructor Rev.1-SpanishOscar RiquelmeAún no hay calificaciones

- A Medix TR-200 BDocumento82 páginasA Medix TR-200 BFederico GraciáAún no hay calificaciones

- Resultado de La Convocatoria para Selección y Vinculación Estudiantes Auxiliares - Proyecto BPUN 548 Laboratorio de Paz Territorial - PosgradoDocumento1 páginaResultado de La Convocatoria para Selección y Vinculación Estudiantes Auxiliares - Proyecto BPUN 548 Laboratorio de Paz Territorial - PosgradoJuan Camilo Leal BalcarcelAún no hay calificaciones

- Tarea Administracion de La MercadotecniaDocumento7 páginasTarea Administracion de La MercadotecniaMulti VentasAún no hay calificaciones