0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

381 vistas238 páginasM. Clásica Problemas

mecanica

Cargado por

Angel CarrascoDerechos de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Nos tomamos en serio los derechos de los contenidos. Si sospechas que se trata de tu contenido, reclámalo aquí.

Formatos disponibles

Descarga como PDF o lee en línea desde Scribd

0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

381 vistas238 páginasM. Clásica Problemas

mecanica

Cargado por

Angel CarrascoDerechos de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Nos tomamos en serio los derechos de los contenidos. Si sospechas que se trata de tu contenido, reclámalo aquí.

Formatos disponibles

Descarga como PDF o lee en línea desde Scribd

LAGRANGIAN

HAMILTONIAN

MECHANICS

Solutions lo the Exercises

LAGRANGIAN

ees |)

HAMILTONIAN

MECHANICS

Solutions to the Exercises

Published by

‘World Scientific Publishing Co, Pe. Ld

‘POBox 128, Fare Road, Singapore 912805

USA office: Suite 1B, 1060 Main treet, River Bdge, NI 07661

UK offce: $7 Shelton Stet, Covent Gardea, London WC2H SHE,

Brish Library Cataloguing-n-Publication Data

‘A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Libary.

LAGRANGIAN AND HAMILTONIAN MECHANICS: SOLUTIONS TO

‘THE EXERCISES

Copyright © 1999 by World Scientific Publishing Co. Pe. Lid.

All rights reserved. Ths book. oF pars thereof, may not be reproduced in any form or by any means,

‘lectronic or mechanical, including photocopying recording or any information storage and retrieval

{stem now known orto be invented, withou writen permission from the Publisher.

For photocopying of material inthis volume, please pay a copying fee through the Copyright

‘Clearance Cente, Inc, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. In this ease permission to

‘Photocopy isnot required from the publisher.

ISBN 981-02-3782-0

‘This book sprinted on acid-ie paper.

Printed in Singapore by UtoPrint

PREFACE

This book contains the exercises from the intermediate/advanced classical

rangian and Hamiltonian Mechanics (World Scientific Pub. Co, Pte.

1996) wogeter wit their complete slations. In few of the exercises I

hhave seen fit to make minor changes in these are marked by asterisks. Also,

Tice fa Be 0 weal pe ‘mini research

“The present wor is intended primarily for instructors who ae using Lagrangian

‘and Hamiltonian Mechanics in thelr course. It is Roped that it

Se aera nd that twill accasonly provide new

{ngghts, Instructors may also wish to photocop jtions to those exercises

which their sudens have had prsulardficuty

"tis book may aso be ved, topeer wit Lagrangian and Hamiltonian

‘Mechanics, by hose who are stodying mechanics on their own, In this case I strongly

urge the individuals to make serious efforts to work out a substantial number of the

relevant exercises on completing their study of each chapter and before looking at what I

tave waiten bere. Only in iis way wil ch individuals come face to face with, and

hopefully overcome, the various difficulties which the exercises present. Exercises,

whether ental or physical, re meant tobe done, not read about!

Melvin G. Calkin

‘alifax, Nova Scotia

September, 1998

Preface

(CHAPTER I

Exercise 1.01

Exercise 1.02

Exercise 1.03

Exercise 1.04

Exercise 1.05

Exercise 1.06

Exercise 1.07

Exercise 1.08

Exercise 1.09

Exercise 1.10

Exercise 1.11

Exercise 1.12

Exercise 1.13

Exercise 1.14

Exercise 1.15

Exercise 1.16

Exercise 1.17

Exercise 1.18

CHAPTER II THE PRINCIPLE OF VIRTUAL WORK AND

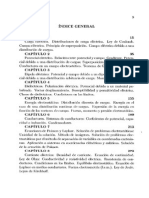

CONTENTS

NEWTON'S LAWS

D’ALEMBERT'S PRINCIPLE

Exercise 2.01

Exercise 2.02

Exercise 2.03

Exercise 2.04

Exercise 2.05

Exercise 2.06

Exercise 2.07

Exercise 2.08

Exercise 2.09

Exericse 2.10

u

2

12

4

4

15

18

2

32

33

38

a

a1

41

sos

as

48

49

viii Contents

CHAPTER IIT LAGRANGE'S EQUATIONS

Exercise 3.01

Exercise 3.02

Exercise 3.03

Exercise 3.04

Exercise 3.05

Exercise 3.06

Exercise 3.07

Exercise 3.08

Exercise 3.09

Exercise 3.10

Exercise 3.11

Exercise 3.12

Exercise 3.13

Exercise 3.14

Exercise 3.15

CHAPTER IV THE PRINCIPLE OF STATIONARY ACTION

OR HAMILTON’S PRINCIPLE

Exercise 4.01

Exercise 4.02

Exercise 4.03,

Exercise 4.04

Exercise 4.05

Exercise 4.06

Exercise 4.07

Exercise 4.08

Exercise 4.09

Exercise 4.10

Exercise 4.11

Exercise 4.12

st

st

92.

53

54

55

7

58

SIRTIIAS

B

8

83

87

88

1

93,

94

96

Contents

CHAPTER V__ INVARIANCE TRANSFORMATIONS AND

CONSTANTS OF THE MOTION

Exercise 5.01

Exercise 5.02

Exercise 5.03

Exercise 5.04

CHAPTER VI_ HAMILTON'S EQUATIONS

Exercise 6.01

Exercise 6.02

Exercise 6.03

Exercise 6.04

Exercise 6.05

Exercise 6.06

Exercise 6.07

Exercise 6.08

Exercise 6.09

Exercise 6.10

Exercise 6.11

Exercise 6.12

Exercise 6.13

Exercise 6.14

Exercise 6.15

CHAPTER VII_ CANONICAL TRANSFORMATIONS.

Exercise 7.01

Exercise 7.02

Exercise 7.03

Exercise 7.04

Exercise 7.05

Exercise 7.06

Exercise 7.07

Exercise 7.08

Exercise 7.09

Exercise 7.10

Exercise 7.11

ix

101

101

103

105

106

10

10

10

112

113

113

14

116

18

120

122

125

127

128

131

134

138

138

139

140

14

143

45,

146

148.

150

151

153,

x Contents

CHAPTER VII HAMILTON-JACOBI THEORY

Exercise 8.01

Exercise 8.02

Exercise 8.03

Exercise 8.04

Exercise 8.05

Exercise 8.06

Exercise 8.07

Exercise 8.08

Exercise 8.09

Exercise 8.10

Exericse 8.11

Exercise 8.12

Exercise 8.13

CHAPTER IX ACTION-ANGLE VARIABLES

Exercise 9.01

Exercise 9.02

Exercise 9.03

Exercise 9.04

Exercise 9.05

Exercise 9.06

Exercise 9.07

Exercise 9.08

Exercise 9.09

Exercise 9.10

Exercise 9.11

Exercise 9.12

CHAPTER X _NON-INTEGRABLE SYSTEMS

Exercise 10.01

Exercise 10.02

Exercise 10.03

Exercise 10.04

157

157

158

161

164

165

168

im

174

7

178

181

184

188

192

192

194

197

199

207

2u1

213,

214

215

217

221

221

222

25

27

CHAPTERI

NEWTON'S LAWS

Exercise 1.01

‘A particle of mass m moves in one dimension x ina potential well

Ve Vo tan®(rx/28)

‘where Vo and a are constants. Find, for given total energy E, the position x asa function

Of time and the period + of the motion. In particular, examine and interpret the low

energy (E << Vo) and high energy (E>> Vo) limits of your expressions.

Solution

Energy conservation yields.

‘fini? + Vo tan?(x/28) = E.

This canbe rearranged to give

“Ff ex . af costrey2a)dx

2 J ,,JB-Vown*@ay2a) V2 J, JE- C+ Vo)sin*(mx2a)

‘To do the x-integration, we set

‘The motion is thus given by (Fig. 1)

»(2)- Re)

2 (Chapter I: Newton's Laws

Ex. 1.01, Fig. 1

‘The motion is periodic with period

coda,

‘The turning points +A of the motion are given by

For B << Vo we have A/2a <> Vo we have

w(t)

0, now dropping the arbitrary phase,

EAE FE ++)

m_ x RE

Bek r-2na oe -Z Bi @n ste wih 0,9 Oahe2-~.

Exercise 101 3

‘Thats,

xu [Eta tan, or ~ FE tea ep

‘The integers n,, must be chosen appropriately; see Fig. 2.

Ex. 1.01, Fig.2

In this Limit the particle oscillates back and forth at constant speed -/2E/m between rigid

walls at x. 28, ‘This is to be expected, since in this limit the potential approximates the

“infinite square well potenial®

V=0 for inlea

V-+@ for ixiva

4 (Chapter I: Newton's Laws

Exercise 1.02

For each of the following central potentials V(r) sketch the effective potential

Ven) Ey +VO,

and use your sketch to classify and draw qualitative pictures ofthe possible orbits.

@ — Voy= fe? 3D leotropic harmonic oeclator

©) V@)=-V¥, for r Eo the radius

oscillates back and forth between turning radii ry and r, and the orbit looks qualitatively

ike Fig. 2.

Ex, 1.02, Fig. 2

‘The motion ofa particle in this potential is studied in detail in Exercise 1.14. It tums out

that the orbit is actually an ellipse with geometric center atthe force center (Fig, 3).

Ex, 1.02, Fig. 3

6 (Chapter I: Newton's Laws

(0) The effective potential is

12/2? -V, for ra

[U2 /2ms* for r>a

For r-+0 the term L3/2m2* dominates and Vyq —*®. For r-+0 Vgy—=0 from

above. Further, Veq has a discontinuity of V, at r=a. There are two posibiltes for

‘Veer, depending on the magnitude of V,. These are shown in Fig. 4. For V, > L2/2ma?

the effective potential goes negative (Fig. (a) whereas for V; and then increases back to infinity. The orbit looks qualitatively like Fig. 6.

Exercise 1.02 7

Ex. 1.02, Fig. 6

In fact, since in this case the particle never encounters a force, the orbit is a straight line

‘which passes by the poteatial region, Fig. 7.

ty

Bx. 1.02, Fig.7

For situation (4) in Fig. (4) the orbit radius decreases from infinity to a minimum

13 <4 and then increases back to infinity, The orbit again looks qualitatively like Fig. 6,

In fact, since in this case the particle encounters a force only at r=a the orbit is

‘composed of staght line segments, Fig. 8.

Ex. 1.02, Fig. 8

(©) The effective potential is

8 Chapter I: Newion's Laws

The shape of Veq depends on the magnitude of the dimensionless combination of

perimeters, Ufamk. For Lfamk<1, Vay =-W/? (Pig. 9(0)) whereas for

Lm 1, Vey & +1? ig. 90).

Ex. 1.02, Fig. 9a) Bx. 1.02, Fig. 900)

For E>0 and L?/2mk < I (situation (1)) there is no inner tuming radius and the particle

spiral in tothe force center. ‘The orbit sa capture orbit like Fig. 10.

Ex. 1.02, Fig. 10

Indeed, since L= bImE where b isthe impact parameter, we can write the condition

for capture as b? O and L?/2mk>1

(Gituation (3), the orbit is a scattering orbit like Fig. 6.

@) The effective potential is

ek

Veal) = aaa

For 1-+0 the term H/o" dominates and. Vuq~* 2. For r—» the tem 12/2?

dominates and Veg -* 0 from above. There is one axis crossing at

Exercise 1.02 9

that is, at 1? = 2mk/L?. There is one extremum (a maximum) at

Ver Pak

Naar, +e

@ ae

+ The value of the effective potential at its extremum is

‘Veqr(max) = L*/16m7k = b*E7/4k where b is the impact parameter. The resulting

effective potential is shown in Fig. 11.

Ver a,

Ex. 1.02, Fig. 11

For E> Vyy(max) and thus b* < 4k/E (situation (1)) the orbit is a capture orbit like Fig.

10, The capeure cross section i8 Cage = bux = 20(K/E. For E-< Var (max) and

initial orbit radius less than «[4mmk/L? (situation (2) the obit has an outer turing radius

but aguin no inner turning radios and the orbit spirals in to the force center. For

B< Vyq(max) and inital radius greater than /4mk/L? (situation (3) the orbit is &

secanerng obit like Fig. 6.

(© The effective potential is

B

Veale sey -k

For 1+0 the tr 12/2m? dominates and Vyq >. For r—~-2 the tem 12/2mi?

again dominates (the exponential causes the second term to decrease faster than any

‘negative power of r, as r-» © ) and Vyq -* 0 from above.

"To detemine the shape of Vag in between, we fst check whether or not ther

are any ani crossings Gn view ofthe ining Bebuvior there rust be nro or an eve

bet of them) These oor tradi ow

10 (Chapter I: Newton's Laws

al?/amk = are™.

‘The righthand side of this equation, a a function of ar, is shown in Fig. 12.

(oexpar)y _(@)

03679 4

/ ©)

10 c

Bx. 1.02, Fig. 12

‘The peak in Fig. (12) is at ar~1 andthe height ofthe peakis Ye = 0.3679. Thu, ifthe

dimensionless combination of parameters a.?/2mk is greater than 0.3679, there ae n0

axis crossings (situation (a)), and if aL?/2mk is less than 0.3679, there are two axis

‘rossings (situation b)). i

ich WC BEM check whether or not here are any extreme, These occur at radi for

al? mk = (ar/2XL+ are".

The sight-hand side of this equation, as a function of ar, is shown in Fig. 13.

(oxRXL+aryexp(-ar) @

0.4200 +

/ @)

16

Bx. 1.02,Fig. 13

‘The peak in Fig. (13) is at ar = (1+-V/5)/2 = 1.618 and the beight of the peak is 0.4200.

‘Thus, if al?/2mk is greater than 0.4200, there are no extrema (situation (a)), and if

‘aL?/2mk is less than 0.4200, there are two extrema (situation (b).

‘The possibilities for Vgq are shown in Fig. 14,

Exercise 1.03 "

a?

042 < a

Bx. 1.02, Fig. 14(0) Ex, 1.02, Fig. 14(0) Bx. 1.02, Fig, 14(0)

‘Sinaations (1) and (2) in Fig. 14 give bound orbits as in Ex. 1.02, Fig. 2, and situations (3)

and (4) give scattering orbits as in Ex. 1.02, Fig. 6.

Exerclae 1.03

‘The first U.S, satellite to go into orbit, Explorer 1, which was launched on January 31,

1958, had a perigee of 360 km and an apogee of 2549 km above the earth’ surface. Find:

(@) the semi-major axis,

(©) the ecceatriity,

(©) the period,

of Explorer I's orbit. The earth's equatorial radius is 6378 km and the acceleration dve to

sgxavity atthe earth's surface is g = 9.81m/s?.

Solution

‘The minimum and maximum radi of Explorer's orbit are

a(1-¢)=360+6378~6738km and a(l+e)=2549+.6378 =8927km.

‘The semi-major axis is thus a= $(6738-+8927) = 7833km and the eccentricity is

8927 - 6738 i ee

© Forragrag “O1*: The period ofthe orbits given by

xo Bak,

Tom

Rather than looking up the gravitational constant G and the mass M of the earth in a

handbook, it s simpler to observe thatthe gravitational field atthe surface of the earth is

= GM/R? = 9.81m/s?, and thus

oo 25, (7.833 x10)5 = 6895s = L92hr.

‘osix (6378x107

2 ‘Chapter I: Newton's Laws

Exercise 1.04

‘Mars travels on an approximately eliptical obit around the Sun, is minimam distance

from the Sun i aboot 138 AU and fs maximum distance i about 167 AU (I AU

‘mean distance fom Eath o Sun), Find

(the semmajor exis,

Diecaenty,

¢ :

of Mar obit.

Solution

‘The semi-major axis of Mars’ orbit is

a= 4.386167 -15340,

nd the cccenticiy is

167=138

“Lorei3e” 8%

‘The periods given by

xo pe

Tou"

Rather than looking up the gravitational constant Gand the mass M of the Sun,

simpler to observe that for Barth

year AU,

snd thus for Mars

‘sin years = (a, in AU = (1.53) = 1.88,

Exercise 105

‘The most economical method of traveling from one planet to another, the Hohmann

transfer, consists of moving along a (Sun-controlled) elliptical path which is tangent to

the (approximately) circular orbits ofthe two planets. Consider a Hohmann transfer from

Earth (orbit radius 1.00 AU) to Venus (orbit radius 0.72 AU). Find, in units of AU and

year:

(@) the semi-major axis ofthe transfer orbit,

() the time required to go from Earth to Venus,

(©) the velocity “kick” needed to place a spacecraft in Earth orbit into the transfer orbit.

Exercise 1.05 13

In this problem ignore the effects of the gravitational fields of Earth and Venus on the

spacecraft.

Solution

(2) The maximum radius ofthe trnster orbit equals the radius of Earth's rit (1.00 AUD,

and the minimum radius equals the radius of Venus’ orbit (0.72 AU). The semi-major

axis of the transfer orbit i

= 40.00 +0.72)=0.86 AU.

(©) The period « ofthe transfer orbit is (see Exercise 1.04)

roa = (0.86% = 0.80 year.

‘The time to go from Earth to Venus is half the period, $(0.80) = 0.40 year.

(©) The energy ofthe spacecraft, per unit mass, at Earth orbit radius rg is given by

126M

ae te

where v isthe speed ofthe. (On the right we have expressed the total energy of,

Be pacer fr ut mika aso be ekrunjr bls Ce males Tas

equation gives

‘Newton's second law shows thatthe speed vp of the Earth around the Sun is given by

vy M.

a

2

y 5 1

(Y\ og- fap t

(3) -2-B--ae

30 v/vp =0.915. Hence the velocity "kick" Av= v- vg needed to place the spacecraft

into the transfer orbit is given by Av/vg =~0.085. Since the speed of the Earth is

‘Yq = 2m AU/year, this yields Av = ~0.534 AU/year (= -2.53km/3).

4

Exercise 1.06

Halley's comet travels around the Sun on an approximately elliptical orbit of eccentricity

= 0.967 and period 76 years. Find:

(a) the semi-major axis of the orbit (Ans. 17.9 AU),

(b) the distance of close sh of Halley's comet to the Sun (Ans. 0.59 AU),

(©) the time per orbit that Halley's comet spends within 1 AU of the Sun (Ans. 78 days).

Solution

(@ The semi-major axis ofthe orbit of Halley's comet is given by Kepler's third Inw (see

Exercise 1.04), a= v% = (76)% = 17.9 AU.

(®) The minimum distance of Halley's comet to the Sun is a(1~e) = 0.59 AU.

© The inwantaneous disace of Halley’ comet tothe Sn andthe centre anomaly y

Eat-ecasy.

{In particular, the eccentric anomaly corresponding to a distance of 1 AU is given by

1

Fag 7! 0.6 Teosy,

‘so = 0.218 radians. The corresponding time is then given by Kepler's equation

vresiny = @a/a}t

which becomes

0.218 -0,967sin0.218 = 25/76),

80 t= 0.107 year =39 day. The total time per orbit that Halley's comet spends within

TAU of the Sun is 2x39 = 78 days.

Exercise 1.07

Define a "season asa time interval over which the true anomaly increases by 1/2. Find

the duration ofthe honest season for earth. Take the eccentricity of ear’ crit tobe

Solution

‘The tre anomaly 0 for the earth, measured from perihelion, and the eccentric anomaly

'y are related by

1s

where ¢ = 0.0167 isthe eccentricity of earth's orbit. This equation can be waitten,

e+ cos8

Trecosé

cosy =:

For the shortest “season” the true anomaly increases from ~7/4 to 2/4, and the eccentric

‘anomaly increases from ~y to y where

cosy = 20167 cos/) |

— 140.0167 cos(74/4) ate

‘This yields y = 0.7737 radians. Kepler's equation (with tin years),

2nt = y~esiny = 0.7737 ~0.0167sin0.7737 = 0.7620,

then shows that t increases from -0.1213 to 0.1213, so the duration of the shortest

"season" is 2x 0.1213 = 0.2425 year = 88,59 days. "Compare this with "winter"

(= 89.00 days)

Exercise 1.08

A satellite of mass m moves ina circular orbit of radius ao around the earth.

(2) A rocket on the satellite fires a burst radially, and as a result the satellite acquires,

‘essentially instantaneously, a radial velocity u in addition to its angular velocity. Find the

seri:mujer nis the eecenoicity, and the aientaton ofthe eliptel obit into which the

satelite is thrown.

(b) Repeat (a), if instead the rocket fires a burst tangentially.

(©) in both cases find the veloity ick required to throw th stlit into parabolic

it

Solution

[Newton's second law shows that

mvj _ ik

mye,

a

0 the initial speed of the satelite is vp = /k/miag. The initial energy is

odavg-£--Lmg ==,

Eo=>mvo 5652 ea!

16 (Chapter I: Newton's Laws

‘and the initial angular momentum is

Lo = mVvotg = akg -

(a) A radial kick changes the energy of the satellite. Since the velocities vo and u are

perpendicular to one another, the final energy is

E-Ep+ imi?

Expressing the inal and final energies in terms ofthe semi-major axes ofthe crit, we

ve

‘This can be rearranged to give the relation between the intial and final semi-major axes,

a

Ba-3.

‘A radial kick does not change the angular momentum of the satelite, 0

BoB

ink” mk"

Expressing this in terms ofthe semi-major axes and eccentricities ofthe orbits, we have

a(1-e?)= a9.

Substituting the preceding expression for ag/a into this equation, we obtain the

eccentricity of the final orbit

em luv.

‘The equation for the final orbit is

Beisecosd

F

‘where 0 isthe angle from pericenter. At the kick r = ap and, for u positive, is increasing.

‘The kick thus occurs at @ = +n/2. ‘That is, pericenter is at —n/2 from the point of firing

of the rocket.

Exercise 1.08 ”

For lul-- vo the eccentricity ¢-+1 and the semi-major axis a» such that

a(1~e)-+ ag/2. The satellite is then thrown into a parabolic orbit. The energy put into

the system is av, othe final tot energy is zero, as required.

(®) A tangential kick changes the energy of the satellite. The final energy is

1

2 Eo By + mvgu+ tm

(v9 +) = Em Bo +mvgn +

2

[Expressing the energies in terms of the semi-major axes, we have

k

E+ mvgu+ tu",

ea

‘This can be rearranged to give the relation between the initial and final semi-major axes,

Seei2.

%

‘A tangential kick also changes the angular momentum of the satellite. The final angular

momentum is

L= m(¥o + u)ag = Lo(1 + u/vo).

and thus

Expressing this in terms of he semi-major axes and eccenticites of the obits, we have

oll w/v).

st de tg sin ho i gn ei

en

{Jere

ade)

8 ‘Chapter I: Newton's Laws

For O 22 -1 (the finl velocity is then vo += £2 v) the eccentricity

¢-+ 1 and the semi-major axis a-+ o. The satellite is then thrown into a parabolic orbit.

‘The energy put into the system is Jincey ve)? mv -my3, so the final total

energy i 270, a required.

tis also of interest to consider the case u/vo = 1 (for which the velocity of the

satellite immediately after rocket firing is zero). We then have a ao/2 and e=1, and

the elipae degeoeites into a stnight ine, the satelite faling sought in towards the

center of heath, me *

Exercise 1.09

‘Show that the following ancient picture of planetary motion (in heliocentric terms) is in

sccord with Kepler’s picture, ifthe eccentricity eis small and terms of order ¢? and higher

(@) the earth moves around the sun ina circular orbit of radius a; however, the sun is not

atthe center of this circle, but is displaced from the center by a distance ea;

() the earth does not move uniformly around the circle; however, a radius vector from a

point which is on a line from the sun to the center, the same distance from and on the

Opposite side of the center as the sun, tothe earth does rotate uniformly.

Exercise 1.09 19

Solution

@

Earth

vs

Zz o

Center Sun

Ex. 1.09, Fig.

For an off-center circular orbit (Fig. 1) we have

a? ar? seta? + 2earcosd,

1s follows from the trigonometric cosine law. This yields

EAfeTaATG~eons0 1 -eon8 feat

‘On the other hand, for an elliptic orbit we have (Lagrangian and Hamiltonian Mechanics,

pages 12 and 13)

2

1=t 21 ~ecos0~e*sin 0+

a” Trecos8

“The two expansions agree to onder

©

Earth

a

‘Center "Sun

Ex. 1.09, Fig.2

Applying the trigonometric sine law to the two smaller triangles in Fig. 2, we have

sin($-or)=esinot and sin(@-4)=esind.

Newton's Laws

‘These yield, to order €”,

Grotsesinate- and 0-9 sexing s fe?sin2g

0 forthe “ancient picture” of planetary orbits we have

= t+ 2esinut +6? sin2ate---

On the other hand, for a Keplerian orbit we have (Lagrangian and Hamiltonian

‘Mechanics, page 18)

@-2esind + fe” sin26+--

Inversion gives

On ots 2esinuts fePsindans-,

which agrees with the "ancient picture" to order e.

Exercise 1.10

(@) Show that

20-1 50088

(the standard form for a conic section, on setting the eccentricity € = 1 and the semi-latus-

rectum p= 2ro) is the equation of a parabola, by translating it into cartesian coordinates

‘with the origin at the focus and the x-axis through pericenter.

(©) A comet travels around the Sun on a parabolic orbit. Show thatthe distance r of the

‘Comet from the Sun i related tothe time t from peribelion by

Besng fae

‘where distances are measured in AU and time is measured in

(©) If one approximates the orbit of Halley's comet near the Sun by a parabola with

7 = 0.59 AU, what does this give forthe time Halley's comet spends within 1 AU of the

‘Sun?

(@) What is the maximum time a comet on parabolic orbit may spend within 1 AU of

the Sun?

Exercise 1.10 a

Solution

(@) The equation for the orbit,

22-1 +0090,

can be transformed into cartesian coordinates (x.y) by multiplying it through by r and

setting =x? +y? and roos0 =x. We obtain

2to-xa qty.

‘Squaring and simplifying this, we then find

a

y

x00

‘which is indeed the equation of a parabola in cartesian coordinates.

() To find out how r depends on time, we tum tothe energy equation

and set E=0 and L? » 2mkro to obtain

1a. Ky

qn +p

Muliplying by +, rearranging, and integrating then gives,

PE, f'n of" [yt

feof ghee [ breeze

Since E[ii = VGH = 25 AUM/year, this becomes

ant 242i

‘with distances now in AU and time in years.

fr=%.

2 (Chapter I: Newton's Laws

(© For rq =0.59AU and r= LOOAU the preceding equation gives t= 0.1047 year, so

the time, in the parabolic approximation, that Halley's comet spends within 1 AU of the

sun is 2t = 0.2094 year = 76.5days. Compare this with the actual time of 78 days (see

Exercise 1.06).

(@) We set r= 1.00 and adjust ro to give maximum time t. This occurs for

at v2 1429) _ 23:

mi Sere tp St

sete mma

rare E (tered) rE 3,

so t= (I/3n)year = 38.7Sdays. ‘The maximum time a comet on a parabolic orbit may

spend within 1 AU of the sunis thus 2t = 77,Sdays.

Exercioe 1.11

[A panicle of mass m moves in a central force field F = ~(k/"*)8.

(@) By integrating Newton's second law dp/dt =F, show that the momentum of the

particle is given by p= po +(mk/L)®, where Po is a constant vector and L is the

magnitude ofthe angular momentum.

(©) Hence show thatthe orbit in momentum space (the so-called hodograph) is a circle

‘Where isthe center and whats the radus of the circle?

(©) Show thatthe magnitude of po is (aak/L)e, where e i the eccentricity. Sketch the

mbit in momentum space for the various cases, e=0, O 1, indicating

for the lat two cases which part of the circle is relevant.

(Gee: Amold Sommerfeld, Mechanics, (Academic Pres, New York, NY, 1952), tans.

Marin O. Stem, p. 33, 40, 242; Harold Abelson, Andrea diSessa, and Lee Rudolph,

“Velocity space andthe geometry of planetary orbits,” Am. J. Phys. 43, 579-589 (1975),

Solution

‘According to Newton's second law the momentum p of « paricle moving ina central

force field -(k/1)# changes at a rate

oo

oat aa

Inthe socond equality we have multiplied and divided by m8, The reason for this is that

we recognize

Exercise 1.11 B

Lem

as the magnitude of the angular momentum, and we also note that,

2. 6g.

at

‘The preceding equation becomes,

‘Since the angular momentum L of a particle moving in a central force field is constant,

‘we can integrate immediately to obtain

where pi cosant vector. To identify this vector, we tke the €-componet ofthe

equation. Since the @-component of pis Le, andthe @-component of py is pocas®

where © isthe angle between py and 8, we Bind

L_ mk

F-TE + pocoss.

‘This can be written

2

L

ni + PE cose,

008

which we recognize as the equation of a conic section with eccentricity © = poL/mk.

‘The magnitude of pp is thus

=

Pome

We also recognize @ as the angle from pericenter, so the direction ofthe vector po is

perpendicular toa line from the fore centr to pericenter.

‘Another way to obtain the magnitude of Po is to write

mk, m3

oy (Chapter I: Newton's Laws

In the second equality we have used the fact that the 8-component ofp is L/r. The first

two terms on the right are 2mE. where E is the toal energy. The equation thus becomes

mk?

ee

;

whee on fi 2D sete emt sin tr ie nyt ep

‘momentum, This then retums us to our previous expression for po,

We now note that

mk

pppoe.

‘This is the equation of a circle, in momentum space, with center at pp and with radius

mk/L. Since po = (mk/L)e, the circle has its center at the origin for circular (e = 0)

orbits (Fig. 1(8)), encloses the origin for elliptic (0 I) orbits Fig. 1().

CO@@

O I whereas waves slow down.

(©) Suppose now thatthe particle is incident at impact parameter bon an attractive square

‘well potential (ig 2).

80s.

Ex. 1.17, Fig.2

The incident angle Oy is given by

sin = b/a

and the refracted angle 8, by

sind = bjna

‘The scattering angle is

6 Chapter I: Newton's Laws

© = 26 -0)),

and thus

con 0/2)= conty end + sntsin

ob?

. he -a +P.

‘The scattering angle ranges from zero at impact parameter zero to a maximum of

2cos"'(/n) at impact parameter a. We can instead express the impact parameter in

terms of the scattering angle. Rearranging and squaring the preceding equation, we find

e

(9-35) (3-2)

which simplifies to

bt atsin? ya

a?” n+ 1-2nc0s@/2

(with 0 < @ <2cos"*(I/n)). For small impact parameter this becomes

o=S-4

Letf, the “focal eng. be the distance from the force centr to he point at which

the scatiered parle crosses the ais of symmety. To find this distance, we drop

been rom ie foe emer ont tio he incoming and egg

Eajeetores. ‘The length of that onto ibe incoming injector is the in er,

tn syne imple ta te lngh of exe perpendclas weequa Ge

Bx. 1.17, Fig.3

We see that

f= bjsin®,

Exercise 117 37

2030/24) ncos@/2 |

For small impact parameter the focal length becomes

fo

X=)

tad is independent ofthe impact parameter, The particles are then brought o@ focus 8

distance f from the force center. ‘These remarks on the focal length hold only for weak

attractive potentials. Otherwise, the geometry changes with the particle crossing the axis

inside the potential region,

(©) The differential scatering cross section is given by

dob [ab

a” Snelael"

2b dd _ n? sin(@/2)c0s(@/2)___n? sin?(@/2)

a d@ ~ n? +1-2ncos(@/2) (n+ 1-2ncos(@/2)"

(=? sin(@/2)(nc0s(@/2) ~ 1)(n ~ cos(@/2))

(a? +1-2ncos(@/2)) :

we have

do __nPa?_ (ncos(€/2)~ In - c0s(@/2))

GQ” 4e0s(872)—(n? +1 2ncos(@/2)*

For large index of refraction (strong atractive potential) the differential searing cross

section becomes

‘and is the same as that for scatering from a hard sphere (strong repulsive potential); see

Exercise 1.16. To understand this, note that the outgoing trajectories in the two cases are

in exactly opposite directions for @ given impact parameter (Fig. 4), so the cross-sections,

‘which are invariant under inversion, are equal.

38 (Chapter I: Newton's Laws

Repulsive

Atactive

Ex. 117, Fig. 4

Exercise 1.18

(@) Show that

$2 cosa8

isthe equation ofthe orbit for a panicle moving in a repulsive potential V(x) = k/r?,

determining andro in terms ofthe energy and angular moment.

a)

T° ame

(Show thatthe impact parameter band saterng angle @ are related by

(Ans.

k (x-6F

2

* Ee@x-6)

(© Show thatthe differential scatering cross section is given by

do tk x-8

GO” Esind 8 2x- OF

a

Exercise 118 39

Solution

(@) The orbit equation is given by

. ee

2 Pae=

Paes

where a? = 1+ 2mk/L?. To do the rintegraton, we first set u= jr, du =—dr/x? to

obain

c éu

@),, Pamela

We then set

u=(V2mE/aL)cosA, du = ~(V2mE/aL)sinAdA.

Integration gives @ = A/a, so the equation of the orbit is.

us l/r (V2mE/aL)cosa0;

thatis, ro/t cosa where rp = ol/-YimE.

(©) Pericenter is at @ = 0, and for r+ the angle a0 -+ =3/2, 0

0, = n/2a.

Expressing @. in terms ofthe scattering angle © by using © = x~2., and «tin terms

‘of the impact parameter b by using L = bv2mE., we find

1 x

ae E

2 2+ Keo

Salvingforb we aban

yak a0?

“E@Qx-8)

40 (Chapter I: Newton's Laws

(©) The differential scaring cross section is given by

do __b |ab|

a0” Fn6|a0)

Since

we have

x-@

42” Esin@ @72x- OF

For small scattering angles this becomes

‘whereas for @ +m it becomes

CHAPTER II

‘THE PRINCIPLE OF VIRTUAL WORK

AND D'ALEMBERT'S PRINCIPLE

Exercise 2.01

10)

i F

1 yms

Use d'Alembert principle to find the condition of static equilibrium.

Solution

Imagine a virual displacement in which the angle O increases by a small amount 30.

‘The mass moves horizontally a distance 8x = £03668, and the applied force F does

work F5x = F£cos060. The mass moves vertically upwards a distance by = fsin080,

and the applied force mg does work ~mg6y=-mgésin80. ‘There are no inertial

forces, so d'Alember's principe gives

£cos050-mgésin880 = 0,

which simplifies to

F=mgind

‘This is the condition of static equilibrium,

Exercise 202

mg

‘Use d’Alemben's principle to find the condition of static equilibrium.

a (Chapter 1: Principle of Virtual Work

‘Solution

Imagine a viru displacement in which the end of the string is mised a distance dx and

‘the weight is thus raised a distance &x/2. The applied force F does work F4x and the

applied force mg does work -mg5x/2. There are no inertial forces, so d'Alembert's

‘rnciple gives

Fox-mgdx/2 =O.

‘This yields F = mg/2, the condition of static equilibrium.

Exercise 203

at

ut

my

Use d’Alemben's principle to find the acceleration of my.

Solution

Imagine a virtual displacement in which m, moves downwards a distance 5x and mz

moves upwards a distance 5x. The applied force, gravity, does work myg8x on m and

=myg6x on mz. The acceleration of my is X downwards, and thet of my is upwards.

‘The inertial force on my is m,% upwards and the inertial work done on my is m8

‘The inertial force on ma is m% downwards and the inertial work done on ma is

~m,X8x. D’Alembers principle gives

(2m, ~ mg)g8x ~ (my + m_)%8x= 0,

$0 the acceleration of my is

xe™M=™y,

mem;

Exercise 2.05 4a

Exercise 2.04

4

sm,

i

Use d'Alembert’ principle to find the acceleration of my

Solution

Imagine a viral displacement in which m, moves downwards a distance 8x and mz

thus moves upwards a disunce 81/2. The applied fore, gravity, does work m,g6x on

m, and ~m2g6x/2 on mz. The acceleration of m, is downwards, and that of ma is

5/2 upwards. The inertial force on m, is m& upwards, and that on ma is my /2

downwards. These inertial forces do work -m,%8x on my and ~(t 5/2)(6%/2) on mp.

DiAlemben’s principle gives

( ~ $ma)g8x- (en, +4m2)¥5x-=0,

so the acceleration of my

Exercise 2.05

2

es

Use d'Alembert’ principle to find the acceleration of mj. Note that in this case the

polley has an upward acceleration A. “Acceleration” means "acceleration relative to the

earth

“ (Chapter I: Principle of Virtual Work

Solution

Imagine a virtual displacement in which m, moves downwards a distance &x and mz

moves upwards a distance 8x. The epplied force, gravity, does work mjg6x on m, and

‘=mgg0x on ma. The acceleration of m, is (X- A) downwards, and that of my is

(+A) upwards. The inertial force on m, is m,(X- A) upwards, and that on m3 is

m,(%+A) downwards. These inertial forces do work -m,(%-A)bx on m, and

=m,(3 + A)&x on my. DAlember’s principle gives

smgdx- mzg8x - m,(j - A)bx- m3 + A)Bx= 0,

which simplifies to

xe MoMesa).

In the frame of the pulley this system, and thus the downward acceleration X of m,

the same as an "Atwood! machine” (Exercise 203) in a gravitational field g+A. Inthe

frame of the earth the downward acceleration of my is

s-n- icmadE=tmah,

Suppose m,>m. Then, if the upward acceleration A of the pulley is small, m,

accelerates downwards and ma accelerates upwards. However, if

A> MaMa,

both masses accelerate upwards.

Exercise 2.06

|:

‘A mass mis attached to alight cord which wraps around frictionless pulley of mass M,

ragius R, and moment of inertia I= fr?dM. Gravity g acts vertically downwards. Use

<'Alemberts principle to find the acceleration of m.

Exercise 2.07 45

Solution

Imagine a virtual displacement in which m moves downwards a distance 8s. The applied

fore, gravity, does work mg8s on m. The inertial force on m is mi upwards and the

‘work it does is ~mi6s. There is no applied work done on the (uniform) pulley, but there

is inertial work. To find this, consider a litle piece dM of the pulley which is at a

distance + from the axle. This piece undergoes a virtual displacement, in the angular

direction, of (1/R) Bs. The acceleration of dM, in the angular direction, is (s/R)8 so the

inertial force on dM, in the angular direction, is ~dM(1/R)8. The inertial work done on

4M is thus -4M(1/R)?86s_(4M also has a radial centripetal acceleration, but this does

‘aconuibue to thee wert). Summing, we hve forthe tot ineal wrt done on

y

=f? a/R? 88s = ~(/R?)3d8,

where I~ fr2dM is the moment of inertia of the pulley. ‘This expression forthe inertial

‘work done in a fixed axis rotation can also be written in the useful general form ~1a8@

where a =3/R is the angular acceleration and 50=s/R is the angular displacement.

Returning othe orginal problem, e'Alembert’s principle now gives

imgbs~ mits ~(1/R2)ibs «0,

‘0 the acceleration of m is

A cylinder of mass M, radius R, and moment of inertia I~ fr?dM rolls without slipping

down an inclined plane. Use d’Alembert's principle to find the acceleration of the

cylinder.

46 ‘Chapter 1: Principle of Virtual Work

Solution

Imagine a virtal displacement in which the cylinder rolls a small distance 6s down the

plane. The only applied force, gravity, does work

swered « Masinads.

To find the inertial work is more difficult. In this virtual displacement the center of mass

of the cylinder is translated s and, because the cylinder rolls, it rotates about its center

of mass through an angle 80 s/R. A litle piece dM of the cylinder at (r,0) thus

‘undergoes a displacement &s down the plane together with a displacement £60 = (&s/R)

in the “angular direction." This latter displacement has components ~r(6s/R)cos@ down

the plane and r(8s/R)sin perpendicular to the plane (Fig. 1).

“down the pane

180 sind]

fant

188 cos8

Ex. 2.07, Fig. 1

4M thus undergoes @ net displacement &s(1~(r/R)cos®) down the plane and

{s(r/R)sin8 perpendicular to the plane. To find the inertial force on dM, we need its

‘cceleration. ‘The acceleration of the center of mass of the cylinder is § down the plane,

and the acceleration of 4M with respect to the center of mass has components x(3/R) in

the "angular direction” and -r(8/R)* (centripetal acceleration) in the “radial direction.”

Resolving these into their components parallel and perpendicular to the plane, we find the

‘et acceleration of dM to be

3 ~1@/R)cos0 + r/R)*sin@ down the plane

and r@/R)sin® +r(/R)Fcos0 perpendicular tothe plane.

‘A more analytical way to obtain these results isto note that the cartesian coordinates of

OM are

xes-rsin@, y= R~reos0,

where x is "down the plane” and y is "perpendicular to the plane.” Differentiating once,

‘we obtain for dM a virtual displacement

bx=8s~rc0s080, by rsin080.

Exercise 2.08 a

Differentiating twice, we obtain for dM an acceleration

= 5- rhcos6 + 167sind, ¥~ rOsin® + 16? cose.

‘The inertial force on dM is -dM times the acceleration, so the inertial work done on

MM is

AMIS ~ 1(/R)cos0 + (YR)? sinBTSs(1~ (s/R)cos0]

~dM[s(/R)sinO + r(4/R)? cos OL8s(*/R)sin 6)

‘= -¢MS[1 - 2(¢/R)cos0 + (1/R)*]8s - dM(7/R)(4/R)sin ds .

(On integration over the cylinder the angle-dependent terms go out and we obtain

awl. Ms (1 + 1/MR?)5s

where I= {174M is the moment of inertia ofthe cylinder about its center of mass. This

expression can be writen in the general form ~MS6s—1a68, where a is the angular

acceleration of the cylinder and 88 is its angular displacement.

“Applying d Alember’s principle tothe original problem, we find

MgsinaBs ~ Mi(L+1/MIR?)8s~= 0,

so the acceleration of the cylinder down the plane is

+m

Exercise 2.08

IRS a

=Q] =

Use d'Alemben’s principle to find the acceleration of m, down the (stationary) plane.

Solution

Imagine a virtual displacement in which m, moves down the plane a distance &s. The

‘mass m, then undergoes a downward vertical displacement Assina. and the appli

48 (Chapter I: Principle of Virtual Work

force, gravity, does work myg6ssina on it. As well, ma moves vertically upwards a

distance &s, and gravity does work ~m2g8s on it. Ifthe acceleration of my is" a” down

the plane, the inertial force on it is m,a up the plane, and the inertial work done on itis

‘mats. The acceleration of m2 is then "a" vertically upwards, the inertial force on itis

‘maa vertically downwards, end the inertial work done on it is ~m,ads. D'Alemben’s

principle gives

mygsina8s~m,g8s-m,abs-m,a8s = 0,

‘0 the acceleration of m, down the plane is

msina-m,

as i

m+,

‘A block of mass m slides on a frictionless inclined plane,

horizontally, the displacement of the plane at time t being some known function x(t).

Use d’Alember’s principle to find the equation of motion of the block, taking as

generalized coordinate the displacement s of the block down the plane. Note that the

acceleration of the block is not "down the plane.”

Solution

Imagine a virtual displacement in which s increases by &s. The mass m undergoes a

downward vertical displacement Sssina. and the applied force, gravity, does work

rmg8ssina. The acceleration a of m is the vector sum of % down the plane and %

horizontal (Fig. 1.

Exercise 2.10 49

‘The inertial foree on the mass is -ma. We need the component ofthis in the direction of

the vinwal displacement, namely -m(+ cosa). The inertial work done is thus

~m(S~ Xeosa)és.. D'Alember's principle gives

mgsinads~_m(+ kcosa)as = 0,

‘0 the equation of motion ofthe block is

Sm gsina ~xcosa.

For i= 0 this reduces to the usual result for an inclined plane. For %> gtana., however,

the acceleration § is negative and the mass m accelerates up the plane.

Exercise 210

‘A block of mass m slides on a frictionless inclined plane of mass M which in tur is free

to slide on a frictionless horizontal surface. Use d'Alembert's principle to find the

equations of motion of the block and the plane, taking as generalized coordinates the

displacement sof the block down the plane andthe horizontal displacement x of the

plane.

Solution

‘The system in this exercise has two degrees of freedom, and there are two independent

virtual displacements. ‘The fist can be taken as in Exercise 2.09, an increase of s by &s.

‘The application of d'Alembert’ principle for this virtual displacement then proceeds as in

Exercise 2.09 and leads to the fst equation of motion

m(+ cosa) = mgsina.

‘The second independent virtual displacement can be taken to be an increase of x by Ox.

In this virwal displacement both m and M move horizontally, so the applied force,

‘gravity, does no work. The incline M has & horizontal acceleration , so the inertial

Work done on it is -M&dx. ‘The mass m has an acceleration a asin Exercise 2.09, with @

horizontal component (cosa +%). The inertial work done on m is thus

=m@cosa + )8x. D’Alembert’s principle gives

-Mibx—_mGcosa + 3)8x = 0,

50 (Chapter it: Principle of Virtual Work

which simplifies to

(cosa + 8) = -Mi

‘This second equation of motion can be integrated to yield

micosa +(m +M)% = constant.

In this form the equation states the fact that the horizontal component of the total linear

‘momentum ofthe system is constant.

CHAPTER II

LAGRANGE'S EQUATIONS

Exercise 3.01

fhe

m

‘A bead of mass m slides without frietion along a wire which ha the shape ofa parabola

y= Ax? with axis vertical inthe eanh’s gravitational Geld g

Fin de Lagrangian king a geerned coor the hsm spleen x

Solution

(@) The kinetic energy ofthe bead is

To bm? +32)= dma + 4a2e?ye?,

and the potential energy is

Ve=mgy=mgAx?,

‘The Lagrangian is thus

‘L(x,8) = fm(1 + 4A2x?)x? - mgAx?,

@) We have

Remassarys, Eo pm(@atsyx?-2mgas,

Say

2.2)8 + mQA2K?

Sele) 7m AAP + BA

‘0 Lagrange’s equation of motion is

m(L+ 4A%x2)x = -m(4A%x)x? - 2mgAx,

2 (Chapter It: Lagrange's Equations

Exercise 3.02

‘The point of suppor of a simple plane pendulum moves vertically according to y= h(t),

‘where h(t) is some given function of time.

(@) Find the Legrangian, taking as generalized coordinate the angle @ the pendulum

‘makes with the vertical.

(b) Write down Lagrange's equation of motion, showing in particular thatthe pendulum

behaves like a simple pendulum in a gravitational field g +,

Solution

(@) The cartesian coordinates ofthe bob are (Fig. 1)

xelsind, — y=h(t)£cos0.

y

he

e

teosa \e

ho ~ £0086 | sino

wind x

Ex. 3.02, Fig. 1

‘The cartesian components of the velocity ofthe bob ae thus

ke Micns8, pha tdsind,

and the kinetic energy is

To (i? +9) = $m(6? + 2iebsin +h),

‘This result can instead be obtained by using the trigonometric cosine law to add the

velocity fin the vertical dretion tothe velocity £8 in the angular direction Fig 2).

Ex. 3.02, Fig. 2

Exercise 3.03 3

‘The potential energy is

V-=mgy = mg(h- ¢e0s6).

‘The Lagrangian is

L=T-V = 4m(0°6? + 2h¢0sind + i?) - mg(h - £c0s6).

© We have

aL. Chas

Fe- mC hesine), — T= miedcosd-mgtsind,

—!—} ~ m(06 + iesin® + hedcos®),

0 Lagrange's equation is

mb = -m(g + fesin8.

“This is the same as the equation of motion of a simple pendulum in a gravitational field

ah.

Exercise 3.03

‘A mass m is attached to one end of a light rod of length ¢. ‘The other end of the rod is

pivoted so that the rod can swing in a plane. The pivot rotates in the same plane at

angular velocity « in a circle of radius R. Show that this "pendulum" behaves like a

‘simple pendulum in a gravitational field g = Ro? forall values of ¢ and all amplitudes of

‘oscillation.

Solution

‘The cartesian coordinates ofthe mass are (Fig. 1)

K=Reosot+ Loos(at+0), y= Rsinat+ fsin(ot +6).

Ex. 303, Fig. 1

54 (Chapter Ill: Lagrange's Equations

‘The cartesian components of the velocity of the mass are thus

ie -Rosinat-Ko+Osin(or+0), y= Rocosut+ Mw +6)cos(ot +8),

and the kinetic energy is

T= }m(i? +5?) }mfR7a? + 2RL0(e + 6)e080+ (w+ 6}

‘There is no potential energy, so the Lagrangian is simply T. We have

at pl ar

Fp TMRwcos0+mea+6), FF

2D). mR twBsind + mes

arlgp) 7 mRCodsing. m6,

mRtoo(w +6)sind,

so Lagrange's equation is

mé*§ = -mRw*tsind.

‘This isthe same as the equation of motion of a simple pendulum in a gravitational field

Ra?

Exercise 3.04

A pendulum is formed by suspending a mass m from the ceiling, using a spring of

‘unstretched length 4 and spring constant k.

(@) Choose, and show on a diagram, appropriate generalized coordinates, assuming that

the pendulum moves in a fixed vertical plane.

(b) Set up the Lagrangian using your generalized coordinates.

(©) Write down the explicit Lagrange's equations of motion for your generalized

coordinates.

Solution

Ex, 3.04, Fig. 1

Exercise 3.05 55

If we choose as generalized coordinates the cartesian coordinates (x.y) with

‘origin atthe point of suspension end with x horizontal and y vertically down (Fig. 1), the

Lagrangian is

Lm dee? + 5?) + may - diy? + y? - 09)?.

‘The second term is (minus) the gravitational potential energy and the third term is,

(minss) the potential energy due to the stretch of the spring. Lagrange's equations are

mie -kx(l-fo/r), my =mg-ky(1- 6/2),

z

Ray’

If, instead, we choose as generalized coordinates the polar coordinates (r,0) with

+ the distance of the mass from the point of suspension and @ the angle the spring makes

‘with the vertical Fig. 1), the Lagrangian is

with ©

L= fm(@? +196) + mgrcos fh(r— 0).

Lagrange's equations are then

if = m6 + mgcos0- K(r~ f0)s

4(mus6)/dt = mr6 + 2mrif = -mgrsin® .

Exercise 3.05

{A double plane pendulum consists of two simple pendulums, with one pendulum

‘suspended from the bob of the other. The “upper” pendulum has mass m, and length £,,

the "lower" pendulum has mass my and length f, and both pendulumes move in the

same vertical plane.

(@ Find the Lagrangian using as generalized coordinates the angles ©, and 0, the

Pendulums make withthe verical

{© Waite down Lagrange’s equations of motion

56 (Chapter It: Lagrange's Equations

Solution

(@) The canesian coordinates of m, are

yn hsind,, yy = £6050),

0 the cartesian components of the velocity of m, are

Hy 48,0050,, jy = -L0, sing.

‘The kinetic energy of m, is

T= }mc3 +5) = 4m 462.

The canesian coordinates of my are

y= G sind, + sind, yg = £40050, + .0058;,

so the cartesian components ofthe velocity of my are

ig = 0,080, + £48,008), fy =i sind, ~ 48, sine,

The kinetic energy of mz is

Ta = hail + 92) = dma CFO + 26 620,64 c09(0, ~ 8,) + G69).

‘The total potential energy is

v

-mgt, cos®, ~m2g(¢,cos®; + £,c0s0;).

‘The Lagrangian is

L= 496} +4, (C6 +26,20,6, cox, -0,)+ G6)

4+ mgt cos0, + myg(l,c0s6, + acos®,).

(b) We have

FE = (+ m Fd, + mhlsb, 010, - 0),

\

4 at : :

ale) mz)676, +m6;¢,62.c08(82 ~ 8;)~ m24y¢,63(6, ~ 6,)sin(®, ~ 8,

= mglyl0,0, sin(@, ~0,)~ (mm, + m3 )gf,in0,,

Exercise 3.05 ”

and

aL atts

3B, 7 Maede + ml L8 c08(02 -0,),

2

4( aL) aj ea

4) = mz63b, + m3ly628,c08(0, ~ 04) mat t364 (6, ~ 6,)sin(, -8,),

aL

Fer matsbiasin(s- 0) matin

Lagrange's equations are

(om, +,)5, + my ly ls8a cos ~0,)~mgfyts64 in, ~0,) = -(m, + mf, sn0,

aati + m3 ts8 cos, ~6,)+ mal, inp ~0,) = -mafgsinds.

In the small angle approximation these become

(om, +m), + malate = Lom, +m Bh.

mall + matis8, ~-m hea,

and are the equations of motion of two linearly coupled simple harmonic oscillators.

| m

‘A bead of mass m slides on a ong straight wire which makes an angle a with, and rotates

with constant angular velocity « about, the upward vertical. Gravity g acts vertically

downwards.

(2) Choose an inte generalized coordinate and find the Lagrangian.

(b) Write down the explicit Lagrange's equation of motion.

58 (Chapter il: Lagrange's Equations

Solution,

(@) Choose as generalized coordinate the distance r of the bead along the wire from the

axis of rotation. ‘The kinetic energy of the bead is then

To}? +0%?sinta),

andthe gravitational potential energy is

V=mgreosa.

“The Lagrangian is

L-4m(?? 40% sina) mgrcosa.

(©) Lagrange’s equation is

mi'= mo*rsin? a - mgcosa.

‘This isthe same asthe equation for one-dimensional motion in an effective potential

Veq = ~}mo?e sin?a.+ mgrcosa.

is 7 & cosa is

This 1 has a maximum at r= + corresponding to an unstable

is potential has tre te ponding to tat

equilibrium point.

Exercise 3.07

| be

‘A particle of mass m slides on the inner surface of a cone of half angle a. The axis of

the cone is vertical with vertex downward. Gravity g acts vertically downwards.

) Choose and show on a diagram suitable generalized coordinates, and find the

(®) Write down the explicit equations of motion for your generalized coordinates.

Exercise 3.08 39

Solution

(@) Choose as generalized coordinates the distance r of the mass from the apex of the

ccone together with the angle @ measured in a horizontal circle around the axis of the

cone. The coordinates r and § are simply two of the usual spherical polar coordinates.

te 6 is, in this problem, fixed at O-a. The

Le fim(? + 262sin?a) ~ mgrcosa.

(©) Lagrange’s equations are

mi ms@*sinta-mgcosa, d(mr%9sin?® a)/ét = 0

‘The second of these equations yields mx%}sin® a= L,, where L, is a constant which can

be identified as the angular momentum of the particle in the vertical (z-) direction,

‘Substituting this into the first equation, we obtain

B

ate ees Hse nares)

‘This is the same as the equation for one-dimensional motion in an effective potential

2

Vert = +mgrcosa.

Ima sin?

Vag has a minimum at 1? »—y— 4, comesponding to suble horizontal

migsin? acosa

circular orbit.

Exercise 3.08

Using spherical polar coordinates (r,8,¢) defined by

xarsin6cosp y=rsinOsing 2=rc0s8,

write down the Lagrangian and find the explicit Lagrange’s equations of motion for a

particle of mass m moving in a central potential V(r).

6 Chapter Il: Lagrange's Equations

Solution

The components of the velocity of a particle in spherical polar coordinates are ¢ in the r-

direction, 10 in the 8-direction, and rpsin@ in the @-direction. Since these are mutually

‘perpendicular, the speed v of the particle is given by

vai? +76? 4 r7GPsin?0,

snd its kinetic energy by

To dmv? = }m¢e? +176? + 124? sin?6),

‘Alteratively this can be obtained by transforming the expression

Tadm(i? +? +2)

for the kinetic energy in cartesian coordinates, by setting

x= rsin0cosp, i= tsinOcosg + 16cosOcos§ - rpsinOsing,

=rsindsing, j= sinGsing + fDcosOsing + psino0s4,

210080, im tcos0- rind.

If the particle moves ina central potential V(r), the Lagrangian is

La T-V = 4d(i? +176? + 179? sin?6)- Ver).

Webave

ee ni. ra 2. metGsinte,

a eee Meee

Ls mar? +§2sin2@)- 2, Ls msG2sin cost a.

Le emrdt santo), LamAPsinvons, Hao,

‘so Lagrange's equations in spherical polar coordinates for a particle moving in central

potential are

ae vo

4 (mi) = ma(6? + fPsinte)- VO,

Sa%) - m#sind00s0,

4 ruin?) «

qt sin’ 8), 0.

Exercise 2.09 GI

Exercise 3.09

For some problems paraboloidal coordinates (E,1,¢) defined by

K=Encoss y= Ensing 2=4@?-n7)

tum oot to be convenient

(a) Show that the surfaces & = const. or n= const. are paraboloids of revolution about

the zaxis with focus atthe origin and semi-latus-rectum &° or 1.

(©) Express the kinetic energy of a particle of mass m in terms of paraboloidal

‘coordinetes and their first time derivatives.

(Ans. T= 4mm(8? + 1? (8? + i?) + 4men?64)

‘Solution

(@ Paraboloidal coordinates (&,7,.¢) are defined by

x=Encos¢, y=Ensing, 2=4(6?-n7).

‘Note also that the cylindrical coordinate p (the distance from the z-axis) is

pada ty? =tn

‘and that the spherical polar coordinate r (the distance from the origin) is

reqitayted = }@t +n?)

We have

reek? and r-zen,

Setting r= yp +2” in these and solving for 2, we find

ey

7 Th

ee

fixed-§ ones open in the negative z-direction and the ixed-n ones open in the positive z-

direction (Fig. 1).

ef

a (Chapter Ill: Lagrange's Equations

= constant

Ex. 308, Fig. 1

(2) The element of distance in paraboloidal coordinates is obtained most easily from that

in cylindrical coordinates,

(ds)? = (dp)? + p7(49)? + (a2),

by setting

dp=Bén+nds and dz=Edk—ndn

together with p= Eq. This gives

(49? = © + (68)? + Cony?) +8n2(09)?.

‘The kinetic energy of a particle of mass m is then

todn( St) Lala? entfe+it) +88")

in parnboloidal coordinates.

Exercise 3.10

‘The motion of a particle of mass m is given by Lagrange’s equations with Lagrangian

L=exp(at/myT - V)

where a isa constant, T = }m(X? + j? + #2) isthe kinetic energy, and. V = V(x.y2) is

the potential energy. Write down the equations of motion and interpret.

Exercise 3.11 6

Solution

We have

cms,

a :

2. 4 (-av/ax),

s0 Lagrange’ equation for xis

mi = ak - aV/ax

with similar equations for y and z. These equations can be combined into the single

vector equation

ni = -af-VV.

This is the equation of motion for a particle of mass m which is acted on by a

conservative force -VV together witha frictional force a which is proportional tothe

‘velocity ofthe panicle.

Exercise 3.11

‘A system with two degrees of freedom (x.y) is described by a Lagrangian

La fim(ai? + 201g + 692) pk(ax? + 2bxy +69)

where a, b, and c are constants, with b?

‘motion and thereby identify the system. Con:

in particular the cases a=c=0,b» 0

and ac, b=0.

Solution

Weave

a a

oo

a 3

Lemire, H--rexsey,

a oy .

so Lagange’s equations ee

(ak + bj) = ~k(ax + by),

(bi + 69) = -k(bx +cy).

“a (Chapter Il: Lagrange’s Equations

‘These can be written in matrix form

of clit bh

1 we multiply both sides ofthis equation by the matix reciprocal to [t 4] (ote that

bc

the reciprocal exists ifthe determinant ac ~ b? of the matrix is nor-zero), we obtain

mi = -kx,

my = ~ky.

‘These are the equations of motion of a two-dimensional harmonic oscillator (a particle of

‘mass m constrained to move in the xy-plane and pulled towards the origin by a spring of,

‘zero unstreiched length and spring constant k). The usual Lagrangian

Ly = fi? + §2)— dk(a? +)

(kinetic energy minus potential energy) for this system is obtained by seting a= ¢= 1

and b=0. Itis clear from this example, however, that it is sometimes possible to find

‘other Lagrangians which lead tothe same equations of motion. ‘Thus, for example, if we

take a= 0 and b= we getan equivalent Lagrangian

Ly-mijy-bay,

Whereas if we take a=

= Land b= 0 we get an equivalent Lagrangian

mi? ~ §2)~ pe(x? ~ 2).

Exercise 3.12

‘The Lagrangian for two particles of masses m, and m, and coordinates r, and 3.

interacting via a potential V(e, ~F2), is

L= bmi + $mafal - Vers -12).

(2) Rewrite the Lagrangian in terms ofthe center of mass coordinates R= TUSL* Sata

m +m

and relative coordinates = ry — Fa.

(©) Use Lagrange's equations to show that the center of mass and relative motions

separate, the center of mass moving with constant velocity, and the relative motion being

like that of a particle of reduced mass —™22_ in potential Vi).

+m

Exercise 3.12 65

Solution

(@) The coordinates +, and r2 of the particles, in terms of the center of mass coordinates

R and the relative coordinates r, are (Fig. 1)

Re Mor and ry eR-— Boe,

m+n mm +m,

my

Mr

m

m1

T

Ongin

Ex. 312, Fig. 1

i m

sna tal

+AU? -vER)

2m+m,

(©) Lagrange's equations for R and r ere

: mm, 2)

(my +m) = ig VO,

(rm tmit~0 and uae

‘The first of these shows that the center of mass moves with constant velocity, while the

second shows thatthe relative motion isthe same as that of a particle of “reduced mass”

EABL-in pce Veo.

CI (Chapter Mt: Lagrange's Equations

Exercise 3.13°

Consider the motion ofa free particle, with Lagrangian

Lea f(a? + 9? +2),

as viewed from a rotating coo

te system

X'mxcos@+ysin®, y'=-xsind + ycos0,

‘where the angle @ = 6(1) is some given function of time.

(@) Show that in terms of these coordinates the Lagrangian takes the form

Lio fafa? + 97? 42%) 4 2007" — y't)¢0%(K? +>]

where «= d0/dt isthe angular velocity.

(©) Write down Lagrange’ equstions of motion and show that they look like those for &

particle which is acted on by a "fore." The part ofthe "force" proportional to w is called

the Coriolis force, that proportional tow? is called the centrifuge! force, and that

proportional to do/dt is called the Euler force. Identify the components of these

forces.”

Solution

(2) To determine the Lagrangian to be used in a routing cartesian frame, we transform

variables, setting in L

x=x'cos6-y'sin®, 'c0s0~ y'sin® ~ ox'sinO - wy'cos®,

= x'sind + y'cos0, in + ¥'c0s8 + ax’cos®-wy'sin®,

‘where © = d/t isthe angular velocity ofthe rotating frame, We thus find

nf 'c0s0- sind ~on'sind -wy'c0s0)? +

+(X'sin® + ¥'cos6 + cox’ cos - wy’ sind)? + (2'*

edly? 42% e209 -y)4 whee sy)

(0) We have

aL nk! - muy’,

7 moy',

|

Ee my +mox’,

om

Exercise 3.14 or

so Lagrange’s equations in the rotating frame are

mi’ = 2moy' + mo*x’ + m(da/di)y',

mj! = -2mui' + mo?y’ - m(du/d)x’,

mi'=0.

The righthand sides ofthese equations are she components ofthe "inert fre” which

in the rou say acts on cle. ‘The terms proportional to © are

the "Coriolis fore” _ pes oe

F (Coriolis) = @moj’,~2mot’,0)= -2me x’;

the terms proportional to «* are the “centrifugal force”

F'(centrifugal) = (meo?x’,mio*y',0) = ~meo x (a xr");

and the terms proportional to du/dt are the “Euler force"

F'Eules)- (me

‘The Euler force is zero ifthe rotation is uniform.

Exercise 3.14

() Write down the equations of motion resulting from a Lagrangian

Lm f(a? + 92 + 22)- Vin) + (CB/2ONaF -Y¥),

and show that they are those for particle of mass m and charge ¢ moving in a central

potential V(¢) together with a uniform magnetic field B which points in the z-direction.

(©) Suppose, instead of the inertial cartesian coordinate system (x,y,2), we use a rotating

system (x',y'.2’) with

Xexcoswt+ysinot, y'=-xsinot+yeoswt, 2’ =z.

‘Change variables, obtaining the above Lagrangian in terms of (x',y',2') and their first

time derivatives.” Show that we can eliminate the term linear in'B by an appropriate

choice of « (this is Larmor’s theorem: the effect of a weak magnetic field on a system is

to induce a uniform rotation at frequency w, the Larmor frequency).

68 (Chapter Ill: Lagrange's Equations

Solution

Weave

z Sent

oe a *

SfY ng By 88) ag

atlae) 7 2c alae)"

‘These can be combined into the single vector equation

V+ (/o)ExB

(where B= Bk) and are the equations of motion, in an inertial frame, of a particle of

‘mass m and charge e in a potential V together with a uniform magnetic field B in the 2-

direction.

(®) The Lagrangian in a rotating frame can be obtained by transforming the variables as

in Exercise 3-13. The first term in L is the same as the Lagrangian in Exercise 3-13 and

‘so transforms the same; the second term V(r) is invariant; and the third transforms as

AY -yRea xy yk! +00"? +),

‘The Lagrangian in the rotating frame is thus

and the Lagrangian reduces to

1? ag? ob 1 eo? (x? + y"2

Lim 5mGi?? +97? +27) Vi — mak (x? +".

It now contains only second order terms in the magnetic field. ‘These are small if the

‘magnetic field is weak.

Exercise 3.15 co)

Exercise 3.15

Show that the equations of motion of an electric charge ¢ interacting with a magnet of

‘moment m can be obtained from a Lagrangian

La EMve +4Mavis + (/e)ve

where

is the vector potential atthe charge due to the magnet.

(Y. Aharonoy and A. Casher, “Topological Quantum Effects for Nevtral Particles,” Phys.

Rev. Let. $3, 319-331 (1984).

Solution

First consider the charge. We have

a

omy +Ea,

ice

Af aL) ay dre Cdk yy Wve [dm rr,

B/E) oy, Me 89M oy, Me [am +, VA

) at edt at {{z irgatght 10s Ya) Ve |

xe AY].

Sale ¥en) Al * Elle ~ ¥en) VeA + (We ~

e e

Lagrange’s equations forthe charge are

ay, 1dm fr,

ota of Mdm.

Mee [edt “ieee

2x ext)]Srexexh

:

Now

By -VexA

the magnetic field due to the magnet atthe location of the charge, The term in square

brackets,

is the electric field due to the magnet at the location of the charge. It consists of two

pars: the first isthe electric field due to the time-dependence of the magnetic moment;

0 (Chapter Ill: Lagrange's Equations

the second is the electric field due to the motion of the magnet. The charge thus moves

according to Newton's second law,

M, Me wey +20, xBay

a ¢

bere the gh hand sd isthe sproprinte Loren force wich the magnet exer on the

charge.

Now consider the magnet Although Lagrange's equations canbe obtained inthe

usual way, its simpler to observe thatthe Lapraglan is unchanged on interchanging the

Subscript © and m everywhere (but the quantty A. changes sign). Applying this

sein 1 Lagrange guns forthe che, we obth Lagange eqn for

magnet,

am, (.ta-te)_¢

AEP (o tate) Ling 2) (0 XA).

Note that,

Mn Oe,

Me dt ao at

‘0 the total mechanical momentum M,¥, +M,¥. is constant. The preceding equation

‘needs to be rewritten so we can interpret it. First note thatthe quantity

Byres

in the first term on the right is the electric field due to the charge at the location of the

‘magoet. Then in the second term set

Aw -mxE,,

‘and hence find

OVA = Va x (mx E,) = (mV Ey.

Here we have used the vector identity Vx (ax) = a(V-b)-b(V-a)+ (b-Vja~(a-V)b

together with the fact that V,,E, = 0. We then have

Mn de m9)

Me Ge SG EH vale

‘The first term in the round brackets,

Exercise 3.15 n

1

rere

is the magnetic field due to the moving charge at the location of the magnet. We thus

obtain

at)

‘The term in round brackets is the magnetic field in the rest frame of the magnet. This is

the correct equation of motion for the magnet, as is discussed more fully in Lagrangian

‘and Hamiltonian Mechanics.

My Ma = 2S KE, + (o-Vq)(B,~

CHAPTER IV

‘THE PRINCIPLE OF STATIONARY ACTION

‘OR HAMILTON'S PRINCIPLE,

Exercise 401

Consider a modified brachstochrone problem in which the particle has non-zero inital

speed vo. Show that the brachistochrone is again a cyclo, but with cusp h = v3/2g

higher than the inital poin.

Solution

In this modified brachistochrone problem the speed of the particle when i has fallen a

distance yi

vedo 2ey,

and the expression forthe travel time becomes

* Ire Gy/axy?

ate [feel ay,

I, We+2y

‘The integrand ofthis expression,

is yaa?

Foy.dy/dx)= sores 7

does not depend explicily on x, so forthe required cuve the quantity

=

v8 + Deyn + @y/dn)

is constant. Itis convenient to set vj = 2gh and then set

(b+ yXL+ (dy/dx)?) = 28

where h and a are constants with the dimensions of "length." Rearranging this and

integrating, we find

Exercise 4.02 B

earn.

‘The y-imtegration can be performed by setting

hty

(cos) and dy =asingdp

toobaain

xe aff (-cosg)dp = af-sing)~@ -singa)]

where > is determined by the condition h = a(1-cos¢p). The preceding two equations

describe cycloid which has a cusp at ($= 0.x =-a(@0~singg).y =A) and which

passes through the initial point (@ = $o,x = 0,y = 0) (Fig. 1). The constant a must be

chosen so that the cycloid passes through the final point (x,,y;).

Guy)

Ex. 4.01, Fig. 1

Exercise 4.02

‘A bead of mass m slides without friction slong a wire bent inthe shape of a cycloid

xn ag-sing) y= a(l~coss).

Gravity g acts vertically down, parallel to the y axis.

(4) Find the displacement s along the cycloid, measured from the bottom, in terms of the

parameter @.

(®) Write down the Lagrangian using s as generalized coordinate, and show that the

motion is simple harmonic in s with period independent of amplitude. Thus the time

required for the bead, starting from rest, to slide from any point on the cycloid to the

bottom is independent ofthe starting point. What is this ime?

" (Chapter 1V: Principle of Stationary Action

Solution

(@) The element of distance ds along the cycloid is given by

(4s)? = (6x)? + Gy)?

= 23[ ~cosey? + sin? @dg)?

= 202(1- cosg)(do)?

= 44? sin? (9/2\(49)"

ds = 2asin(9/2)46,

‘The displacement s, measured along the cycloid from the bottom (6 = x), is thus

= 2aftsin(g/2)db = ~4acos(@/2)

‘and ranges from —4a to 4a as we move along the cycloid from cusp (= 0) to cusp

(@= 22).

() The kinetic energy ofa bead of mass m which slides along the cyeloid is

To 4m

‘The gravitational potential energy of the bead, measured from the bottom of the cycloid,

‘V = mg(2a- y) = mga(1 +.cosq) = 2mgacos?(/2) = 4m(g/4a)s?.

“The Lagrangian is thus

L = fms? ~}m(g/4a)s?,

and Lagrange’s equation is

i ~ -m(g/4a)s.

‘This is the equation of motion ofa simple harmonic oscillator with angular frequency

= g/4 and period x= 2n/n = 2n/40/g. The time required for the bead, starting

from rest to slide from any point onthe éycloid tothe bottom is one-quarter period,

af andi independent ofthe sat point.

Exercise 4.03 15

Exercise 4.03

Novelists have long been fascinated with the idea of a worldwide rapid transit system

consisting of subterranean passages crisscrossing the earth.! Public interest in

‘sublerrancan travel rose sharply when Time magazine? commented on a paper by Paul W.

Cooper, “Through the Earth in Forty Minutes"® This paper, while repeating some easler

‘work. Served asa catalyst for a numberof other papers onthe subjec® to which you may

‘Wish to refer in working the present exercise. ‘Take the gravitational potential within the

carth to be $(g/R)r? where g isthe gravitational field atthe surface and R isthe radius

ofthe earth (thereby neglecting the non-uniform density of the earth.

(@) Fist show that a panicle stating from rest and sliding without friction through a

straight tunnel connecting two points on the surface of the earth executes simple

harmonic motion, and that the time to slide from one end to the other is to = xYR/E

(~42.2min) independent ofthe location ofthe end points.

(®) Now consider the curve 1(6) the tunnel must follow such thatthe time for the particle

to slide from one end to the other is minimum. Set up the appropriate variational

principle, and show that

al %&

Tea Pe

isa first integral of the resulting Euler-Lagrange equation. Here r= fo at the bottom of

the tunnel (9 is the minimum distance to the center of the earth), Rearrange this and

{integrate to obtain the equation of the curve,

‘where 0 is measured from the bottom of the tunnel. The angular separation between the

tend points on the surface ofthe earth is thus given by

49 = x(1~r9/R).

(©) Introduce a parameter @ with

‘See Marin Gaoer, Scleifc American, Seplember 1965, p. 10-12, commenting on an ate by LK.

‘Edwards, Hlgh Speed Tube Tanjoaton” Selenite Anerson, Avg 195, 930-40,

1966, pp, 42-43

3Paal W. Coopes, “Through te Eat in Forty Mules." Am, Phys. 34, 68.70 1960).

‘See Phlip G. Kinmee, "An Example of te Need for Adequate References," Am, J Poy 34,701 (1966).

SGiullo Vecalan, “Teresvial Bracistochrone,” Am. J. Phys. 34,701 (1966): Russell L. Mallet,

Commeots on “Through tbe Earth in Forty Minus,” Am, J. Pays. 34, 702 (1966); L. Jackson Laslet,

“Trajectory fo Minium Transit Tune Through the Earth" Am. J. Pops. 34, 702-705 (1966); Paul W.

(Cooper, "Purber Commentary on "Trough the Earth in Fety Miouies," Ar. Phys. 34, 703-704 (1966).

16 (Chapter 1V: Principle of Stationary Action

so $=0 atthe bottom and $= 27 at the ends of the tunnel. Show that the equation of

the curve takes the form

Aasfeeed)-He Bho

o- (End) Be.

‘Show that this isthe equation of a hypocycloid, which is the curve traced by a point on

the circumference of a circle which rolis without slipping on another circle.

®

In this case the larger circle is the great circle route, of radius R, connecting the end

points on the surface of the earth, and the smaller circle has radius a= 4(R ~f9) (its

circumference is thus the distance between the end points onthe surface). The parameter

4s the angle shown in the figure.

(© Now consider the time dependence of the variables. Show in particular that 6 varies

linearly with time, 4 = 2x(W/t), where <= xpy/1— (Fo/R) is the time to slide through the

sinimum-time-tunnel from one end to the other. Compare + with tg for end points 700

Jkm apart on the surface.

Solution

(a) For a particle of mass m which starts from rest atthe surface and which slides without

friction through a tunnel through the earth, conservation of energy gives

inv? + $m(g/R)P? = 0+ dm(a/R)R?.

Exercise 4.03 n

Ex, 4.03, Fig. 1

First suppose thatthe tunnel is straight and let s denote the displacement along the tunnel

from the bottom, where r assumes its minimum value rp (Fig. 1). We thea have

ves and Posters,

and the conservation of energy equation becomes

$ms? + $m(g/R)s* = }m(g/RMR? 15).

‘The leftchand side of this equation, asa function of s, has the same form as the expression

forthe total energy of a simple harmonic oscillator with angular frequency

wn eR

‘The motion ins is thus simple harmonic. The time to for the particle to slide from one

end of the tunnel tothe other is half a period,

te afa= x (Rg = 42.2 min,

(b) Now consider the curve the tunnel must follow to make the travel time

a

for the particle a minimum. Itis convenient to use plane polar coordinates (r,8), in terms

‘of which the element of distance ds is

(ds)? = (4x)? + 17(40)*.

‘The speed v ofthe particle is given by energy conservation (see par (8)

vv? = (g/RYR? -F?),

‘The expression forthe travel time becomes

B (Chapter IV: Principle of Stationary Action

“,

ane (e100 + ag,

ae

‘We wish to find the curve r= r(8) which makes this a minimum. The integrand,

pa [R [eeddor +?

8 vr

does not contain the independent variable © explicitly, so for the required curve the

quantity

ea: £ 1 2

9(dr/48) 48 BR =P Yanaor ee

is constant, We set

1 2 to

We? fay er Roe