Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Imam Al-Bukhari's Contribution

Cargado por

Idriss SmithDescripción original:

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Imam Al-Bukhari's Contribution

Cargado por

Idriss SmithCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Home > Hadith > The Science of Hadith:

State Of Islam

Imm al-Bukhr's contribution to the development of hadth literature, and the importance of his al-Jmi al-Sahh

by Ola bint al-Shoubaki

"O People, no prophet or messenger will come after me and no new faith will be born. Reason well, therefore, O People, and understand words which I convey to you. I am leaving you with the Book of God (the Qurn) and my Sunnah (the life style and the behavioral mode of the Prophet peace be upon him), if you follow them you will never go astray." These words, addressed by the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) to the Muslims during the Farewell Pilgrimage, were the final confirmation for the believers of the importance of preserving a record of the words and actions of their beloved Prophet (peace be upon him), themselves regarded as a secondary revelation, inspired by the Creator himself. Whether or not permission was granted by the Prophet (peace be upon him) to his companions for an official record remains a topic of debate in scholarly circles, fuelled by the existence of contradictory hadth on this topic.[1] Evidence suggests, however, that there were some Companions who made such notes, in collections which later came to be known as Sahfahs (scripts), for their own guidance.[2] By the end of the first century, corruption began to taint the realm of hadth. Political and theological divisions within the ever-expanding Islamic Empire led to the quotation, misquotation, and fabrication of hadth by rivaling factions in support of their cause, a practice which instigated the comment of sim al-Nabl (d.212), "In nothing do we see pious men more given to falsehood than in Tradition."[3] The legal jurists themselves were now ever-increasingly in need of legitimizing traditions to use in their jurisprudence. Effectively, the urgency arose firstly, to collect and record the hadth, and secondly, to devise a method through which to differentiate the authentic from the unauthentic. The first official decree to begin the compilation of hadth was not until the Umayyad reign, set by the Caliph Umar b. Abd al-Azz. The resultant works, however, are no longer extant, thus little can be said concerning their plan, method, or contents.[4] These primary works, arranged according to a structured subdivision of chapters according to their subject-matter, were known as musannafs, the earliest and best known available example of which is the Muwatta of Mlik b. Anas, founder of the Mliki school of jurisprudence. Mlik's Muwatta was not a traditional collection of hadth, for "it's intention is not to sift and collect the 'healthy' elements of traditions circulating in the Islamic world but to illustrate the law, ritual and religious practice, by the ijma recognized in Medinan Islm, by the sunnah current in Madna, and to create a theoretical corrective, from the point of view of ijma and sunnah, for things still in a state of flux."[5] Another type of hadth collection which appeared was that of the musnad arrangement, which was arranged by the name of the companion under whose name the hadths were reported. The famous musnads of Ahmad b. Hanbal, Ishq b. Rhawayh and

Uthmn b. Ab Shaybah are all remnants of this era. Although there is some confusion concerning the chronological appearance of the two, we may assume that both appeared at the end of the first and the beginning of the second century.[6] By the third century, however, neither type of collection seemed to be entirely sufficient. Although the musannafs aimed to "provide the lawyer with a handbook of tradition in which he could readily look up the ipsissima verba of the Prophet (peace be upon him) and thus silence an objector"[7], they "diluted by legal additions the literature of the hadth proper and made its study subservient to legal discussions."[8] The musnads, on the other hand, were difficult to use, for the hadth on common topics were in different sections, nor did they "discriminate between authentic and da'if material." These factors were probably what influenced Ishq b. Rhawayh (d.238/852) to remark that he wished someone would compile a book which comprehensively gathered only the authentic hadth.[9] Although delivered casually, the remark was received in a more inspiratory light by one of his students, Muhammad b. Isml al-Bukhr (d. 256/870). Following this incident, al-Bukhr sifted, over sixteen years, through some 600,000 hadths known to him in search of only those which were authentic, from which he chose to include only 7,397[10] in his compilation al-Jmi al-Sahh. The title of the work itself is interesting, and indicates one aspect of al-Bukhr's contribution to the development of the science of the hadth; the first word which appears, al-Jmi, means that the collection contains hadths relating to all of the following eight topics: i-Belief, ii-Laws and Rulings, iii-Riqq (piety and ascetism), iv-db (manners) of eating, drinking, travel etc, v-Tafsr (Qurnic exegesis), vi-Tarkh and Siyar (historical and biographical matter), vii-Fitan (crises expected towards the end of time), and viii-Manqib (virtues) and Mathlib (defects) of various people, places etc.[11] Although there were other jmi collections prior to that of al-Bukhr's, such as that of Sufyan al-Thawri, what is important here is that alBukhr compiled the first Jmi which contained only authentic (sahh) hadth. As for what al-Bukhr considered made a hadth authentic, he did not state the exact canons of criticism which he applied, and thus later scholars made personal attempts at inferring them from the text.[12] It would seem pertinent to examine, at this point, what features made the Jmi such an important work in its field, such that it was worthy of later coming to be known as the most authentic book after the Qurn. Principally, al-Bukhr's hadth were composed of three aspects, the matn (the actual text itself), the isnd (chain of transmission) and the tarjamatul bb (the chapter heading). The matn was the most important of the three, and the science of hadth was developed as a way of authenticating what information the matn carried. Having said this, it is understandable that the matn demands less attention than the isnd and the tarjamah. This provoked some criticism, Siddiqi commented that al-Bukhr "pays little attention to the probability or possibility of the truth of the actual material reported by them."[13] Guillaume attributes the occurrence of contradictory hadth within the same chapter to this, for "if the matn contained an obvious absurdity or an anachronism there was no ground for rejecting the hadth if the isnd was sound."[14] However, traditional Islamic scholars of hadth have derived criteria which they propose define the acceptability of a text.[15] For example, the narration should not contradict the basic laws of nature. Also, it should not doubt the notion of Allh's perfection, such as we find in the forged narration, "Allh created the horse and caused it to run until when he perspired, Allh created himself with his perspiration." Nor should it state that which contrasts what is stated in the Qurn, for

example the alleged hadth "An illegitimate child will not enter Paradise and nor will his progeny until seven generations." This narration contradicts the code of the Qurn: "And no carrier will carry the burden of others." These are a few of the conditions of acceptance of a hadth by virtue of its matn. In direct contrast to this, however, Ibn Abd al-Barr (d.463) and al-Nawawi (d.676) apparently "do not hesitate to assail traditions which seem to them to be contrary to reason or derogatory to the dignity of the Prophet (peace be upon him)."[16] As no supporting reference has been supplied, it is hard to do anything other than take this statement lightly. If we accept the view that al-Bukhr adhered to these conditions, however, and did not overlook the content in favour of the isnd, this would have been a valuable contribution to ridding the hadth literature of icated and weak narrations. The second aspect of al-Bukhr's hadth was that of the isnd. As was previously mentioned, al-Bukhr did not himself state how he examined the authenticity of the isnds. Thus, although later scholars like Al-Hazm and Al-Muqaddas produced treatises on the subject, these sanctions were effectively determined through personal analysis, therefore, betokening small-scaled differences of opinion. Siddiqi, for example, offers a synopsis of al-Bukhr's understanding of what made a hadth authentic; he says, "such traditions as were handed down to him from the Prophet (peace be upon him) on the authority of a well-known Companion, via a continuous chain of narrators who, according to his records, research and knowledge, had been unanimously accepted by honest and trustworthy traditionists as men and women of integrity, possessed of a retentive memory and firm faith, accepted on condition that their narrations were not contrary to what was related by the other reliable authorities, and were free from defects. al-Bukhr includes in his work the narrations of those narrators when they explicitly state that they had received the traditions from their own authorities. If their statement in this regard was ambiguous, he took care that they had demonstrably met their teachers, and were not given to careless statements."[17] Others outlined more detailed and intricate criteria, expanding on Siddiqi's description that the isnd, for example, had to be muttasil ('uninterrupted' if it stops short of the Prophet - peace be upon him - it is known as mawqf), and that there had to be clear evidence that any two consecutive narrators in a chain had met in person. This critical study of authenticating the hadth by virtue of its isnd developed into a science which came to be known as ilm al-jarh wat-tadl ('the science of impugning or confirming [the credibility of the muhaddiths].'[18] Numerous works were composed on this topic, including four by al-Bukhr himself, the most famous of which goes by the name of Kitb al-Rijl al-Kabr. In this work, al-Bukhr treats some 40,000 men, demonstrating his vast knowledge on this topic. It may seem surprising therefore, that despite his seemingly stringent, thorough, practice in this field, there should remain room for criticism. Surprisingly, the first criticism came from al-Bukhr's contemporary and compiler of the second most authentic hadth collection entitled al-Sahh: Muslim b. Al-Hajjj (d.261). Muslim, unlike al-Bukhr, did not insist on proof that two consecutive narrators had met, but rather sufficed with the possibility of this meaning, he accepted hadth mu'an'an ('so-and-so reported on the authority of so-and-so) in the same category as those reported with worse like 'I heard from', or 'I saw', and the like. Indeed, in the introduction to the Sahh, Muslim attacks an anonymous contemporary on this issue, saying that 'the expression an implies personal contact unless there is direct evidence to the contraryHe accuses his opponent of inconsistency on the ground that there are several hadth muanan which are accepted as

genuine, e.g. Hisham an abhi....it would be ridiculous to suppose that there was no personal contact between the two men and to refuse to regard the tradition as genuine.'[19] The anonymous opponent seems to be al-Bukhr himself.[20] Al-Bukhr was also criticized for inconsistency on the grounds that he uses less exacting criteria for the hadth which form the basis of some of his chapter headings, and those which corroborated the main ones. In some of these cases, the isnds are partially or fully omitted, and sometimes even relies on weak authorities. In fact, the there are approximately 1,725 'suspended' (muallaq) traditions in his Jmi.[21] This led some scholars to conclude that al-Bukhr, although regarding these hadths as genuine, was unable to find a genuine isnd for them[22], and thus cast doubt over our scholar's fundamental premise of compiling only those undoubtedly authentic hadths. If we examine, in particular, the issue of omitting the isnds, however, we will find that the criticism is a weak one. According to Ibn Salh and al-Nawawi[23] the total number of hadth excluding repetitions amounts to 4,000[24]. This means that there were 3,2753,397 hadths in the Jmi which were repetitions, either because they are indicating a difference of opinion, or because they are being used under various chapters. It is extremely likely, for the sake of comprehensiveness, that while al-Bukhr repeated the hadth, he did not see the same need to repeat the isnd. The issue of weak traditions, however, still remains, and provoked figures such as al-Draqutn (d. 385) to compose an entire book (al-Istidrkt wa'l-Tatabbu) in demonstration of the weakness of many canonical hadths, including al-Bukhr's. [25] Ayn too, in his celebrated commentary has shown the defects of some of its contents.[26] According to Siddiqi though, alBukhr's inclusion of such hadth was intentional, with specific academic purposes in mind, explained further by commentators on his Sahh.[27] More criticism this time towards the issue of authentication by isnd rather than alBukhr in particular - came from the direction of Joseph Schacht, who studied certain isnds and led him to conclude that 'the isnd itself had consciously been seen and exploited as a weapon of debate in its own right'[28], and therefore was not a reliable source of authentication. This accusation formed an attempt to invalidate the hadth literature in its totality, implying that there was no method to test for its authenticity. However, a silencing counter-criticism was made of Schacht's position by Professor John Esposito of Georgetown University, who said, "Accepting Schacht's conclusion regarding the many traditions he did examine does not warrant its automatic extension to all the traditions. To consider all Prophetic traditions apocryphal until proven otherwise is to reverse the burden of proof. Moreover, even where differences of opinion exist regarding the authenticity of the chain of narrators, they need not detract from the authenticity of a tradition's content and common acceptance of the importance of tradition literature as a record of the early history and development of Islamic belief and practice."[29] The final aspect of al-Bukhr's hadth which deserves some examination is that of his tarjim. This aspect contributes greatly to the peculiarity of al-Bukhr's work, and vastly exposes the visionary genius of al-Bukhr. From his chapter headings, the reader gains insight into al-Bukhr's attitudes in the realms of law, theology and Qurnic exegesis, and as al-Qastalln has said, "Al-Bukhr's fiqh is contained in the headings of his chapters."[30] There is some debate amongst scholars as to when al-Bukhr actually wrote his chapter headings, the strongest opinion of which is that he authored the chapters prior to embarking on his task. Evidence for this view lies in instances where

one finds headings followed by no hadths at all, from which we can infer that there was no authentic hadth known to al-Bukhr on this topic, although he wished to have addressed it. The implications of al-Bukhr 's tarjim have also been debated, for while at times his headings would tackle a legal issue, at others he was found to be forwarding a moral judgement. Likewise, in some instances they agree fully with their respective hadths, while in others the significance is seemingly broader. However, it must be remembered that "in every chapter heading, al-Bukhr kept a certain object in view."[31] And in dividing his work in such a manner, al-Bukhr made the work of the jurists, when attempting to find hadths on certain topics, all the less tasking. If credibility of a work is to be judged through the attendance of committed scholars of the field towards it, then there is no shortage of scholars who have studied and composed works on al-Bukhr's Jmi. It even provoked the emergence of whole genres of literature related to it[32], such as the Mustadrakt, (where the compiler gathers together all the hadth which fulfil al-Bukhr's and Muslim's conditions, but were missed by the two scholars), and the Mustakhrajt, (where the compiler collects additional isnds to add to those cited earlier, thereby strengthening the hadths further), among others. As we have seen, al-Bukhr compiled his work in a time when there was a great need for the authenticity of hadths to be established. He aimed to gather together only the most authentic hadths available to him at the time, under various chapters which would be of interest to the jurist, whilst at the same time not confining his work to the legal realm. What makes his work peculiar to that of his contemporary Muslim's is the tarjim, his stricter attitude towards isnds, and the repetition of hadths, through his "determination to distil as many rulings as the different clauses, even individual words, of a hadth can be made to yield."[33] Although faced with criticism from Muslim and Orientalist scholars alike, much tribute has been made to the accuracy, scrupulous care, and exactitude employed by al-Bukhr. Brockelmann commented, 'He has shown the greatest critical ability, and in editing the text has sought to obtain the most scrupulous accuracy.'[34] And although al-Bukhr was not the first to compose works in the field of hadth, and who made major contributions to their critical study, al-Bukhr "absorbed, sifted, organized and developed earlier writings, and cleared the path for further achievements by succeeding scholars."[35] Although there is much to be gained from free study, the essence of Islm is undoubtedly ingrained in the lives and heritage of the pious ancestors, who lived closer to the time of the Prophet (peace be upon him) and who had seen Islm in the form of practical application rather than mere theoretical arguments and explanations. As well as the valuable works bequeathed to later generations, al-Bukhr also left an irreplaceable example of piety and God-consciousness. He himself, on many occasions, acknowledged that he had not documented a single narration until he had purified his body by taking a bath and offered two units of prayer asking for Allaah's guidance on the matter. Such extraordinary care is not reported to have been taken by any other scholar throughout history. We shall conclude with the words of al-Bukhr's contemporary, Qutayba b. Sad, "If Muhammad b. Isml was among the Companions, indeed he would have been exemplar (to them)."[36] Bibliography

l l

l l

l l

l l

The Encyclopaedia of Islm Abbott, N. 'Hadth Literature II: Collection and transmission of Hadth' in Beeston, A.F.L., Johnstone, T.M., Serjeant, R.B., Smith, G.R., (editors)Arabic literature to the end of the Ummayad period, Cambridge History of Arabic Literature, Cambridge University Press, 1983 Abdul Rauf, M. 'Hadth Literature I: The development of the science of Hadth' in Beeston, A.F.L., Johnstone, T.M., Serjeant, R.B., Smith, G.R., (editors) Arabic literature to the end of the Ummayad period, Cambridge History of Arabic Literature, Cambridge University Press, 1983 al-Bukhr, Muhammad b. Isml, al-Jmi al-Sahh Burton, J., An Introduction to the Hadth, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 1998) Esposito, J. Islm: The Straight Path (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998) Fard, A., Al-Imm al-Bukhr Sahhuhu al-Jmi (Alexandria: Dar al-dawah alSalafyyah, n.d.) Goldziher, I., Muslim Studies, Vols I&II, translation by Barber & Stern, (London: 1971). Guillaume, A., The Traditions of Islm, (Beirut: Khayyat, 1961). Hshim al-Husayni, Al-Imm al-Bukhr muhaddithan wa-faqhan, (al-Qhirah: alDr al-Qawmiyyah li al-Tibah wa al-Nashr, [19--]) 'Al-Jmi al-Sahh: A Review' Compiled by: Students of Jamiatul Imm Muhammad Zakariyya (R.A) Jamia Publication No.1 Al-Khazraj, K., Ghoniem, M., Saifullah, M. & Hannan, J., 'On The Nature Of Hadth Collections Of Imm Al-Bukhr & Muslim', (Islamic Awareness, 1999) Kittani, Y., Al-Imm al-Bukhr wa Jmiuhu al-Sahh, (Jamiyyat Al-Imm alBukhr, n.d.) Al-Raz, Ibn Ab Hatim, Abd al-Rahmn b. Muhammad, Kitb bayn khata Muhammad b. Isml al-Bukhr f tarkhihi, (Beirut: Mu'assasat al-Kutub alThaqfiyyah, [198-]). Siddiqi, M.Z., Hadth Literature: its origin, development, special features and criticism, (Cambridge: Islamic Texts Society, 1993). Weiss, B., The Spirit of Islamic Law, (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1998)

Footnotes: [1] Ab Dwd, for example, cites two subsequent hadiths, the first stating the Prophet's (peace be upon him) command, and the second his forbiddance, (lest it should hinder the integrity of the Qurn) regarding this issue. (Robson, J. Hadth, Encyclopaedia of Islam) [2] Robson, J. Hadth, Encyclopaedia of Islam, also Siddiqi, pg 9 [3] Guillaume, pg 78 [4] Siddiqi, pg 7 [5] Goldziher, Muslim Studies [6] According to Guillaume and Siddiqi, the musnad appeared first on the scene, whereas Abdul Rauf and

others claimed that the musannafs were compiled slightly earlier than the musnads [7] Guillaume, pg 25 [8] Abdul Rauf, pg 273 [9] Siddiqi, pg 56 [10] Abdul Rauf, pg 275 (According to Siddiqi (pg 56) however, this figure is 7,275, which was also the opinion of Imam Nawawi) [11] Siddiqi, pg 10 [12] For example, Al-Hzim in this Shurt al-Aimma, al-Iraqi in his Alfiyya, and al-Ayn and al-Qastalln in their introductions to their commentaries on the Sahh, among others. [13] Siddiqi, pg 58 [14] Guillaume, pg 89 [15] al-Jmi al-Sahh: A Review [16] Guillaume, pg 94 [17] Siddiqi, pg 56 [18] Abdul Rauf, pg 278 [19] Guillaume, pg 86 [20] ibid. [21] Siddiqi, pg 57 [22] Guillaume, pg 27 [23] Al-Jmi al-Sahh: A Review [24] There is some difference of opinion regarding this number. Abdul Rauf puts the number of repetitions at 4,000 (pg 275), while Guillaume states that the number of hadth excluding repetitions is 2,762 (pg 28) [25] Guillaume, pg 94 [26] Siddiqi pg 58 [27] Siddiqi, pg 57 [28] Burton, pg 148 [29] Esposito, pg 81 [30] Guillaume, pg 26 [31] Siddiqi, pg 57 [32] cf: Farid, pgs 130-134 [33] Burton, pg 125

[34] Siddiqi, pg 58 [35] Abdul Rauf, pg 279 [36] Farid, pg 53

También podría gustarte

- Teaching The Art of Speaking by Hazrat Moulana Ashraf Ali ThanwiDocumento29 páginasTeaching The Art of Speaking by Hazrat Moulana Ashraf Ali ThanwitakwaniaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Basics of Uloom-ul-Hadeeth Grade 112Documento22 páginasThe Basics of Uloom-ul-Hadeeth Grade 112Samer EhabAún no hay calificaciones

- Wahhabi SectDocumento14 páginasWahhabi SectHanefijski MezhebAún no hay calificaciones

- Floral Ramadan Planner by Al-MadaarDocumento44 páginasFloral Ramadan Planner by Al-Madaarsaba ambarAún no hay calificaciones

- An SeDocumento184 páginasAn SePak Mantri Pusk PundongAún no hay calificaciones

- Belief in Jinns and AngelsDocumento44 páginasBelief in Jinns and AngelsMonge Dorj100% (1)

- Belief in Jinns and AngelsDocumento44 páginasBelief in Jinns and AngelsMonge Dorj100% (1)

- Preaching Islamic Renewal: Religious Authority and Media in Contemporary EgyptDe EverandPreaching Islamic Renewal: Religious Authority and Media in Contemporary EgyptAún no hay calificaciones

- Exposing the Khawarij Infiltration of the Blessed Muhammadan NationDe EverandExposing the Khawarij Infiltration of the Blessed Muhammadan NationAún no hay calificaciones

- Causality As A Veil The Ash Arites Ibn Arab 1165 1240 and Said Nurs 1877 1960Documento17 páginasCausality As A Veil The Ash Arites Ibn Arab 1165 1240 and Said Nurs 1877 1960handynastyAún no hay calificaciones

- Dua Abdur Rahman SudaisDocumento18 páginasDua Abdur Rahman SudaisAbu IbrahimAún no hay calificaciones

- ImamAlMizziHisBriefIncarcerationAndTheKhalqOfImamAlBukhari PDFDocumento67 páginasImamAlMizziHisBriefIncarcerationAndTheKhalqOfImamAlBukhari PDFAnonymous JWUsx1Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Fallacies of Anti Hadith ArgumentsDocumento10 páginasThe Fallacies of Anti Hadith ArgumentsIbn SadiqAún no hay calificaciones

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Intellectual Achievements of Early Muslim CommunitiesDe EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Intellectual Achievements of Early Muslim CommunitiesAún no hay calificaciones

- Moris, Megawati. (2011) - Islamization of The Malay Worldview - Sufi Metaphysical Writings. World Journal of Lslamic History and Civilization, 1 (2), 108-116Documento9 páginasMoris, Megawati. (2011) - Islamization of The Malay Worldview - Sufi Metaphysical Writings. World Journal of Lslamic History and Civilization, 1 (2), 108-116cmjollAún no hay calificaciones

- Teaching QushashiDocumento42 páginasTeaching QushashiberrizeAún no hay calificaciones

- Fitnatul WahabbiyahDocumento19 páginasFitnatul WahabbiyahShakil Ahmed100% (1)

- Allama Sayyid Murtaza Askari - The Role of Aisha in The History - Volume IDocumento192 páginasAllama Sayyid Murtaza Askari - The Role of Aisha in The History - Volume Iapi-3820665Aún no hay calificaciones

- Islaamic BeliefsDocumento238 páginasIslaamic BeliefsImran Rashid Dar100% (1)

- Nature of The Four MadhabsDocumento16 páginasNature of The Four Madhabsahmed0sameerAún no hay calificaciones

- Bid Ah InnovationDocumento29 páginasBid Ah InnovationAmmar AminAún no hay calificaciones

- Al-Maktubat Al-Haqqiyyah (v.1) (English)Documento60 páginasAl-Maktubat Al-Haqqiyyah (v.1) (English)Dar Haqq (Ahl'al-Sunnah Wa'l-Jama'ah)Aún no hay calificaciones

- Hadyi Al Sari PDFDocumento38 páginasHadyi Al Sari PDFAyeshaJangdaAún no hay calificaciones

- Shaykh Muhammad Salih HendricksDocumento6 páginasShaykh Muhammad Salih HendricksAllie KhalfeAún no hay calificaciones

- Majalis-E-Zikr by Abdul Hafeez MakkiDocumento22 páginasMajalis-E-Zikr by Abdul Hafeez MakkisaadmohammadAún no hay calificaciones

- Was Ghazali A Mere Opponent of PhilosophyDocumento11 páginasWas Ghazali A Mere Opponent of PhilosophyOsaid AtherAún no hay calificaciones

- Biography of Muhammad Ibn Abdul WahhabDocumento9 páginasBiography of Muhammad Ibn Abdul WahhabMuh Alif AhsanulAún no hay calificaciones

- The-Killer-Mistake - Response by Iman Kufr and TakfirDocumento228 páginasThe-Killer-Mistake - Response by Iman Kufr and TakfirNasrulmaAún no hay calificaciones

- Fayd Al Litaf Ala Jawhara Al Tauhid Line 11 141Documento9 páginasFayd Al Litaf Ala Jawhara Al Tauhid Line 11 141Faisal Noori100% (1)

- Banat Suad: Translation and Interpretive IntroductionDocumento17 páginasBanat Suad: Translation and Interpretive IntroductionMaryam Farah Cruz AguilarAún no hay calificaciones

- A Biography of Imam Abu Yusuf (RA)Documento4 páginasA Biography of Imam Abu Yusuf (RA)Waris HusainAún no hay calificaciones

- Unofficial Biography of Shaykh Hamza YusufDocumento4 páginasUnofficial Biography of Shaykh Hamza YusufsdAún no hay calificaciones

- Hadiths of KhawarijDocumento24 páginasHadiths of KhawarijFakruddinAún no hay calificaciones

- KhanqahDocumento31 páginasKhanqahPatrasBukhariAún no hay calificaciones

- Thulaathiyaat Al-Imam BukhaariDocumento9 páginasThulaathiyaat Al-Imam Bukhaarizamama442Aún no hay calificaciones

- Biography Imam SyafieDocumento3 páginasBiography Imam SyafieFiedDinieAún no hay calificaciones

- Versatile PersonalityDocumento44 páginasVersatile PersonalityTariq Mehmood Tariq100% (1)

- Bruinessen Qadiriyya in KurdistanDocumento21 páginasBruinessen Qadiriyya in Kurdistanazraq68100% (1)

- Al-Murji'ah Sect: Its History and BeliefsDocumento4 páginasAl-Murji'ah Sect: Its History and BeliefsTheEmigrantAún no hay calificaciones

- Who Is Al UtbiDocumento6 páginasWho Is Al Utbisarkar999Aún no hay calificaciones

- Talfiq Mixing MadhabsDocumento4 páginasTalfiq Mixing MadhabsradiarasheedAún no hay calificaciones

- Critical Response To Yamin ZakariaDocumento58 páginasCritical Response To Yamin ZakariaJason Galvan (Abu Noah Ibrahim Ibn Mikaal)100% (2)

- Who Are The Murjiah and What Are Their Beliefs - Shaykh Alee Hasan Al-HalabiDocumento7 páginasWho Are The Murjiah and What Are Their Beliefs - Shaykh Alee Hasan Al-HalabiHamid PashaAún no hay calificaciones

- Dialogue With An EvolutionistDocumento51 páginasDialogue With An EvolutionistRizwan Jamil100% (1)

- Imam Ibn Asakir (Rahimahullah) The Greatest of His Era..Documento3 páginasImam Ibn Asakir (Rahimahullah) The Greatest of His Era..takwaniaAún no hay calificaciones

- English Variant Readings Companion Codices and Establishment of The Canonical Text An Analysis The Objections of Arthur Jeffery and at WelchDocumento43 páginasEnglish Variant Readings Companion Codices and Establishment of The Canonical Text An Analysis The Objections of Arthur Jeffery and at WelchNeelu BuddyAún no hay calificaciones

- Forms of Gnosis in Sulami (ICMR 16.4 2005) - Libre PDFDocumento18 páginasForms of Gnosis in Sulami (ICMR 16.4 2005) - Libre PDFyavuzsultan34Aún no hay calificaciones

- The 'Amal of MadinaDocumento12 páginasThe 'Amal of MadinaYecoub GonzálesAún no hay calificaciones

- Book No. 4 Tampering Tafseer Noorul Irfan (FINAL) by Ilyas Ghumman DeobandiDocumento22 páginasBook No. 4 Tampering Tafseer Noorul Irfan (FINAL) by Ilyas Ghumman DeobandiKabeer AhmedAún no hay calificaciones

- 1.3 Ulum Hadith July 2017Documento18 páginas1.3 Ulum Hadith July 2017Nornis DalinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Huzoor Badre MillatDocumento5 páginasHuzoor Badre MillatMohammad Junaid SiddiquiAún no hay calificaciones

- The Refutation That Ash'aries & Maturidis Deny Allah's Attributes and Sidi Abu Iyad FromDocumento4 páginasThe Refutation That Ash'aries & Maturidis Deny Allah's Attributes and Sidi Abu Iyad FromAbdullahFaheemAlMalikiAún no hay calificaciones

- Hadith Book1Documento45 páginasHadith Book1Manzoor AnsariAún no hay calificaciones

- Abrogation of Quran by Sunnah - SG S5 AssigmentDocumento3 páginasAbrogation of Quran by Sunnah - SG S5 AssigmentOliver Miller50% (2)

- Istighatha KawthariDocumento2 páginasIstighatha KawthariAbd Al Haq JalaliAún no hay calificaciones

- Rights of Parents in IslamDocumento7 páginasRights of Parents in IslamAnwar AdamAún no hay calificaciones

- Understanding the Hadeeth (Sayings) of Prophet Muhammad in the context of the Qur'anDe EverandUnderstanding the Hadeeth (Sayings) of Prophet Muhammad in the context of the Qur'anAún no hay calificaciones

- Replies to Critiques of the Book 'The Issue of Hijab': Hijab, #2De EverandReplies to Critiques of the Book 'The Issue of Hijab': Hijab, #2Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Belief in a.N.G.E.L.SDocumento17 páginasThe Belief in a.N.G.E.L.SIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- Belief in The AngelsDocumento3 páginasBelief in The AngelsIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- Physical Characteristics of AngelsDocumento5 páginasPhysical Characteristics of AngelsIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- The Angels and Human BeingsDocumento5 páginasThe Angels and Human BeingsIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- Physical Characteristics of AngelsDocumento5 páginasPhysical Characteristics of AngelsIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- Belief in The AngelsDocumento3 páginasBelief in The AngelsIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- The Trial of The GraveDocumento3 páginasThe Trial of The GraveIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- Belief in The AngelsDocumento4 páginasBelief in The AngelsIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- Attributes and Abilities of AngelsDocumento3 páginasAttributes and Abilities of AngelsIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- Attributes and Abilities of AngelsDocumento3 páginasAttributes and Abilities of AngelsIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- Belief in The AngelsDocumento4 páginasBelief in The AngelsIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- The First Night in The GraveDocumento3 páginasThe First Night in The GraveIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- The Faculty of Hearing of The DeadDocumento5 páginasThe Faculty of Hearing of The DeadIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- Complete - Zaad Al MaadDocumento245 páginasComplete - Zaad Al Maad~~~UC~~~100% (2)

- En Death Is Enough As An AdmonitionDocumento16 páginasEn Death Is Enough As An Admonitionobl97Aún no hay calificaciones

- Benefitting The Dead: Chapter 6 From "Funeral Rites in Islaam"Documento3 páginasBenefitting The Dead: Chapter 6 From "Funeral Rites in Islaam"Truthful MindAún no hay calificaciones

- At-Tadhkirah Fi Ahwalil-Mawta Wal-Akhirah (In Rememberance of The Affairs of The Dead and Doomsday) by Al-Imam Al-QurtubiDocumento400 páginasAt-Tadhkirah Fi Ahwalil-Mawta Wal-Akhirah (In Rememberance of The Affairs of The Dead and Doomsday) by Al-Imam Al-QurtubiFather_of_ZachariasAún no hay calificaciones

- DeathDocumento5 páginasDeathIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- The Resurrection - IslamDocumento47 páginasThe Resurrection - IslamAbdul MominAún no hay calificaciones

- Life and DeathDocumento96 páginasLife and DeathAhmad NoorAún no hay calificaciones

- Treasures in The Sunnah 1Documento154 páginasTreasures in The Sunnah 1TarekAún no hay calificaciones

- Forty Encounters With The Beloved Prophet - Blessings and Peace Be Upon Him - His Life, Manners and CharacteristicsDocumento160 páginasForty Encounters With The Beloved Prophet - Blessings and Peace Be Upon Him - His Life, Manners and CharacteristicsMeaad Al-AwwadAún no hay calificaciones

- The Prophet's Methods For Correcting People's MistakesDocumento160 páginasThe Prophet's Methods For Correcting People's MistakesMeaad Al-Awwad100% (1)

- Series of Prophecies in The Bible For The Advent of Muhammad (Pbuh) PDFDocumento48 páginasSeries of Prophecies in The Bible For The Advent of Muhammad (Pbuh) PDFkamcdAún no hay calificaciones

- The Hadith of SlaughterDocumento2 páginasThe Hadith of SlaughterIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- The Obligation of Adhering To The SunnahDocumento5 páginasThe Obligation of Adhering To The SunnahIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- Treasures in The Sunnah, A Scientific Approach2Documento130 páginasTreasures in The Sunnah, A Scientific Approach2abu sourakaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Divine HadithsDocumento156 páginasThe Divine HadithsIdriss SmithAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 Arbain Nabhani Sandals ExcerptDocumento5 páginas1 Arbain Nabhani Sandals ExcerptTahmidSaanidAún no hay calificaciones

- Sadl in The Maliki Madhab and It's ProofsDocumento30 páginasSadl in The Maliki Madhab and It's ProofsMAliyu2005Aún no hay calificaciones

- Free Mixing Between Sexes in Islam.Documento3 páginasFree Mixing Between Sexes in Islam.GuidanceofAllahAún no hay calificaciones

- Qunut-Of-Ramadaan 1442H VersionDocumento8 páginasQunut-Of-Ramadaan 1442H VersionSadah AhmedAún no hay calificaciones

- Redbridge Islamic Centre Calender 2019Documento12 páginasRedbridge Islamic Centre Calender 2019Scratchy QAún no hay calificaciones

- Hajj Itinerary 24Documento1 páginaHajj Itinerary 24salmanliyakathAún no hay calificaciones

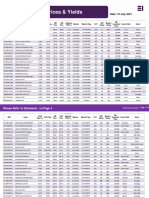

- Sukuk Indicative QuotesDocumento5 páginasSukuk Indicative QuotesAhmedAún no hay calificaciones

- Conditions of SalahPPDocumento11 páginasConditions of SalahPPAyesha waheedAún no hay calificaciones

- Pokok-Pokok Ajaran Aswaja Menurut Kh. Ma'Ruf Irsyad Kudus: Email: Fathur - Rohman@unisnu - Ac.idDocumento13 páginasPokok-Pokok Ajaran Aswaja Menurut Kh. Ma'Ruf Irsyad Kudus: Email: Fathur - Rohman@unisnu - Ac.idHarrySetyantoAún no hay calificaciones

- Shariah Fiqh and Usul Al FiqhDocumento3 páginasShariah Fiqh and Usul Al FiqhManar H. MacapodiAún no hay calificaciones

- أثر القراءات القرآنية ...Documento23 páginasأثر القراءات القرآنية ...بن الشيخ عليAún no hay calificaciones

- Janaja Dua For Baby Boy and AdultsDocumento1 páginaJanaja Dua For Baby Boy and Adultsrakib khanAún no hay calificaciones

- Ahmed Bahgat - Prohibition of Hadiths by MuhammadDocumento30 páginasAhmed Bahgat - Prohibition of Hadiths by MuhammadSmple Trth100% (1)

- Samastha Vidyabhysa Board App - NoveltonDocumento1 páginaSamastha Vidyabhysa Board App - NoveltonAfgraphy AshrafAún no hay calificaciones

- Mesin Pencari Hadits Dan Terjemah Terlengkap PDFDocumento4 páginasMesin Pencari Hadits Dan Terjemah Terlengkap PDFsmp alkhairaat1paluAún no hay calificaciones

- Atiyyah Al Awfi: in The Eyes of MuhadiseenDocumento24 páginasAtiyyah Al Awfi: in The Eyes of MuhadiseenAjsjsjsjsAún no hay calificaciones

- Ballb 6 Sem Family Law 2 (Muslim Law) Paper 4 Summer 2017Documento4 páginasBallb 6 Sem Family Law 2 (Muslim Law) Paper 4 Summer 2017Shashank BhoseAún no hay calificaciones

- Rules Related To A Dying Person: Islamic Teachings in Brief 1Documento18 páginasRules Related To A Dying Person: Islamic Teachings in Brief 1misAún no hay calificaciones

- Ameenahs Store - Book ListDocumento4 páginasAmeenahs Store - Book ListnikbelAún no hay calificaciones

- Ramadhan Timetable 2013 (1433H)Documento2 páginasRamadhan Timetable 2013 (1433H)Ben Sellam OmarAún no hay calificaciones

- Paying Zakat Al Fitr On CashDocumento4 páginasPaying Zakat Al Fitr On CashkannadiparambaAún no hay calificaciones

- Khilafat e RashidaDocumento10 páginasKhilafat e RashidaRizwan IjazAún no hay calificaciones

- Ruling On Keeping Beard in IslamDocumento5 páginasRuling On Keeping Beard in IslamAbdullah Ibn MuhammadAún no hay calificaciones

- قاعدة فقهية تأصيلا وتطبيقاDocumento42 páginasقاعدة فقهية تأصيلا وتطبيقاعبدالله الهاشميAún no hay calificaciones

- Istighathah: Additional Quotes Provided by Mufti Husain KadodiaDocumento5 páginasIstighathah: Additional Quotes Provided by Mufti Husain KadodiatakwaniaAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Perspective: Sahih Al-Bukhari - Book 70 Hadith 575Documento2 páginasIslamic Perspective: Sahih Al-Bukhari - Book 70 Hadith 575LIEBERKHUNAún no hay calificaciones

- Obedience To Tyrannical Muslim Rulers & Is Obedience Only For The Khalifah & Not Rulers of Different Muslim CountriesDocumento7 páginasObedience To Tyrannical Muslim Rulers & Is Obedience Only For The Khalifah & Not Rulers of Different Muslim CountriesAbdul Kareem Ibn OzzieAún no hay calificaciones