Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Eurasia's Hinge: It's More Than Just Energy

Cargado por

German Marshall Fund of the United StatesTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Eurasia's Hinge: It's More Than Just Energy

Cargado por

German Marshall Fund of the United StatesCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Foreign Policy and Civil Society Program

May 2012

Summary: Without energy, the small Caucasian state of Azerbaijan would likely have been an afterthought in the post-Soviet space. But Azerbaijan is much more than an energy hub. It is precisely at the hinge of powerful cultural forces where old empires overlap and modern states compete and it has energy. It is infused with Iranian culture, ethnically and linguistically Turkic, and historically part of the Russian, then Soviet empires, and all three influences are competing for the greatest attention.

Eurasias Hinge: Its More than just Energy

by Joshua W. Walker and S. Enders Wimbush

In early May 2012 in Washingtons venerable Willard Hotel, Governor Bobby Jindal of Louisiana and former Governor Hailey Barbour of Mississippi drew comparisons between their states and the Republic of Azerbaijan as part of a buoyant celebration of Azerbaijans 20-year relationship with the United States. Their sentiments, and those many of the guests, were focused largely on Azerbaijans status as a critical mid-sized energy power connected to world markets, and increasingly to Europe, through important pipeline systems. Indeed, energy is the principal reason most governments and corporations pay attention to Azerbaijan. Energy wealth in todays world is enough to generate interest almost everywhere. Indeed, without energy, the small Caucasian state of Azerbaijan would likely have been an afterthought in the post-Soviet space: a Muslim country deep in the shadows of the Christian civilizations of Georgia with its compelling cultural attachments to Europe, and Armenia with its engaged and potent political diaspora on both sides of the Atlantic. But Azerbaijan is much more than an energy hub. It is precisely at the hinge of powerful cultural forces where old empires overlap and modern states compete and it has energy. Azerbaijan is the sum of three elemental tendencies that accentuate the pivotal nature of its geographic position: infused with Iranian culture, ethnically and linguistically Turkic, and historically part of the Russian, then Soviet empires. Eurasias future is likely to play out in and around Azerbaijan for reasons that are independent of the Caspians energy wealth but are amplified by it. Put differently, Azerbaijans importance to the West goes well beyond oil and gas. From the vantage point of Baku, its strategic universe is increasingly complex and worrisome, if not threatening. To the north, Russia is a lethal cocktail of dysfunctional politics, official corruption, economic torpor, regional fissures, and ethnic shifts all within the cone of a demographic death spiral and powered by resentment at having lost an empire and its corollary, unrequited imperial ambition. Russia has never forsaken its appetite for its former Caucasian possessions. Its wars in the North Caucasus, its attack on Georgia in 2008, and its efforts to impede a settlement between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh are a way to increase its own presence and influence in the region and block Azerbaijans access to Turkey illuminate Russias strategic design. For Russia, the key to this region is Azerbaijan. To the south, Iran is on the cusp of conflict. Azerbaijan shares a 700 kilometer border with Iran, and up to 25

1744 R Street NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 745 3950 F 1 202 265 1662 E info@gmfus.org

Foreign Policy and Civil Society Program

percent of Irans population, according to some estimates, are Azeris. Irans mullahs of Azeri descent have made Baku a special target, as they are mostly Shiite Muslims, and Iranian authorities have never made a secret of their disdain for Azerbaijans independence. Their strategies will resonate in Azerbaijan to the extent that the smaller northern state fails to anchor its citizens in a more potent set of values and lives by them. A destabilized Iran, whether from internal revolution or attack from outside, will pose a special range of challenges for Azerbaijan. It is implausible to imagine that Azerbaijan can be isolated from the resulting turmoil, and therefore it is in the Wests interest to assist Azerbaijan in advancing inoculations of strong civil society antibodies. Yet there is every reason to believe that a stable Azerbaijan linked politically, economically, and militarily to the West can serve as a model for post-conflict Iran, as well as a conduit for the Wests values and ideas. Turkey represents a counterforce to Iran, an important influence impeding Azerbaijan from sliding into Irans orbit. Its links to Azerbaijan have grown steadily, based on common ethnic and linguistic foundations, and there are growing economic, social, educational, political, and military ties. Major energy pipelines connect the two. Former Turkish Prime Minister Abdulfaz Elcibey may have struck close to the mark when he inaugurated the concept of Azerbaijan and Turkey as one nation with two states. Turkeys support for Azerbaijan against Armenian claims on Nagorno-Karabagh has been constant. Yet the Arab Spring, and particularly turmoil in Syria, have exposed institutional weaknesses in Turkish foreign policy that could eventually affect a range of Turkish interests, including Azerbaijan. And Europe, reluctant to give Turkey traction toward full membership, will miss a singular derivative opportunity to pull Azerbaijan into its embrace. Azerbaijan faces difficult challenges in governance, civil society, and democratic development that must be addressed if it is to maintain its delicate balancing act amid these powerful interests and states. But it also boasts important strengths and instincts. A strong sense of national identity, as well as its historic tradition of Islamic modernism, has been a barrier to the inevitable inflow of radical Islamist ideas, though this is a constant worry. It actively seeks strong relations with Europe and the United States, despite the often distracted attention of both. (Washington currently has no ambassador in Baku.) Azerbaijans young

professionals can be found in most Western and Asian capitals and universities today, and its cadre of professional diplomats, prepared increasingly by the globally-linked Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy, are notable. But these strengths and Azerbaijans growing sense of selfconfidence should not detract from the larger sobering picture. Azerbaijans neighborhood grows increasingly dangerous and unstable, while many of the most potent political, economic, and cultural dynamics intersect the small Caucasian country. It is hard to imagine where modest investments from the West that reaffirm Azerbaijans inclination and predispositions might pay a larger dividend, nor where failure to do so could have more extended consequences. Its about a lot more than energy.

About the Authors

Joshua W. Walker is a Transatlantic Fellow and S. Enders Wimbush is the Senior Director for Foreign Policy & Civil Society at the German Marshall Fund of the United States based in Washington, DC.

About GMF

The German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF) is a nonpartisan American public policy and grantmaking institution dedicated to promoting better understanding and cooperation between North America and Europe on transatlantic and global issues. GMF does this by supporting individuals and institutions working in the transatlantic sphere, by convening leaders and members of the policy and business communities, by contributing research and analysis on transatlantic topics, and by providing exchange opportunities to foster renewed commitment to the transatlantic relationship. In addition, GMF supports a number of initiatives to strengthen democracies. Founded in 1972 through a gift from Germany as a permanent memorial to Marshall Plan assistance, GMF maintains a strong presence on both sides of the Atlantic. In addition to its headquarters in Washington, DC, GMF has seven offices in Europe: Berlin, Paris, Brussels, Belgrade, Ankara, Bucharest, and Warsaw. GMF also has smaller representations in Bratislava, Turin, and Stockholm.

About the On Wider Europe Series

This series is designed to focus in on key intellectual and policy debates regarding Western policy toward Wider Europe that otherwise might receive insufficient attention. The views presented in these papers are the personal views of the authors and not those of the institutions they represent or The German Marshall Fund of the United States.

También podría gustarte

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2099)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (73)

- Russia's Long War On UkraineDocumento22 páginasRussia's Long War On UkraineGerman Marshall Fund of the United States100% (1)

- Political History of Modern KeralaDocumento10 páginasPolitical History of Modern KeralaGopakumar Nair0% (1)

- Russia's Military: On The Rise?Documento31 páginasRussia's Military: On The Rise?German Marshall Fund of the United States100% (1)

- Biography of Tan Sri Syed Mokhtar AlDocumento2 páginasBiography of Tan Sri Syed Mokhtar AlNora MazminAún no hay calificaciones

- Holy Quran para 30Documento43 páginasHoly Quran para 30moinahmed99Aún no hay calificaciones

- Women and Islam Fatima Mernisi PDFDocumento238 páginasWomen and Islam Fatima Mernisi PDFrachiiidaAún no hay calificaciones

- Sir Syed Was A Visionary ReformerDocumento3 páginasSir Syed Was A Visionary ReformerNatashashafi75% (4)

- The Iranian Moment and TurkeyDocumento4 páginasThe Iranian Moment and TurkeyGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Turkey's Travails, Transatlantic Consequences: Reflections On A Recent VisitDocumento6 páginasTurkey's Travails, Transatlantic Consequences: Reflections On A Recent VisitGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- The United States in German Foreign PolicyDocumento8 páginasThe United States in German Foreign PolicyGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- The West's Response To The Ukraine Conflict: A Transatlantic Success StoryDocumento23 páginasThe West's Response To The Ukraine Conflict: A Transatlantic Success StoryGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Small Opportunity Cities: Transforming Small Post-Industrial Cities Into Resilient CommunitiesDocumento28 páginasSmall Opportunity Cities: Transforming Small Post-Industrial Cities Into Resilient CommunitiesGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Defending A Fraying Order: The Imperative of Closer U.S.-Europe-Japan CooperationDocumento39 páginasDefending A Fraying Order: The Imperative of Closer U.S.-Europe-Japan CooperationGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Cooperation in The Midst of Crisis: Trilateral Approaches To Shared International ChallengesDocumento34 páginasCooperation in The Midst of Crisis: Trilateral Approaches To Shared International ChallengesGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Why Russia's Economic Leverage Is DecliningDocumento18 páginasWhy Russia's Economic Leverage Is DecliningGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Turkey: Divided We StandDocumento4 páginasTurkey: Divided We StandGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Isolation and Propaganda: The Roots and Instruments of Russia's Disinformation CampaignDocumento19 páginasIsolation and Propaganda: The Roots and Instruments of Russia's Disinformation CampaignGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- The Awakening of Societies in Turkey and Ukraine: How Germany and Poland Can Shape European ResponsesDocumento45 páginasThe Awakening of Societies in Turkey and Ukraine: How Germany and Poland Can Shape European ResponsesGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- For A "New Realism" in European Defense: The Five Key Challenges An EU Defense Strategy Should AddressDocumento9 páginasFor A "New Realism" in European Defense: The Five Key Challenges An EU Defense Strategy Should AddressGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Leveraging Europe's International Economic PowerDocumento8 páginasLeveraging Europe's International Economic PowerGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- China's Risk Map in The South AtlanticDocumento17 páginasChina's Risk Map in The South AtlanticGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Turkey Needs To Shift Its Policy Toward Syria's Kurds - and The United States Should HelpDocumento5 páginasTurkey Needs To Shift Its Policy Toward Syria's Kurds - and The United States Should HelpGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Solidarity Under Stress in The Transatlantic RealmDocumento32 páginasSolidarity Under Stress in The Transatlantic RealmGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- The EU-Turkey Action Plan Is Imperfect, But Also Pragmatic, and Maybe Even StrategicDocumento4 páginasThe EU-Turkey Action Plan Is Imperfect, But Also Pragmatic, and Maybe Even StrategicGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- After The Terror Attacks of 2015: A French Activist Foreign Policy Here To Stay?Documento23 páginasAfter The Terror Attacks of 2015: A French Activist Foreign Policy Here To Stay?German Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- AKParty Response To Criticism: Reaction or Over-Reaction?Documento4 páginasAKParty Response To Criticism: Reaction or Over-Reaction?German Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Common Ground For European Defense: National Defense and Security Strategies Offer Building Blocks For A European Defense StrategyDocumento6 páginasCommon Ground For European Defense: National Defense and Security Strategies Offer Building Blocks For A European Defense StrategyGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Brazil and Africa: Historic Relations and Future OpportunitiesDocumento9 páginasBrazil and Africa: Historic Relations and Future OpportunitiesGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Between A Hard Place and The United States: Turkey's Syria Policy Ahead of The Geneva TalksDocumento4 páginasBetween A Hard Place and The United States: Turkey's Syria Policy Ahead of The Geneva TalksGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Pride and Pragmatism: Turkish-Russian Relations After The Su-24M IncidentDocumento4 páginasPride and Pragmatism: Turkish-Russian Relations After The Su-24M IncidentGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Whither The Turkish Trading State? A Question of State CapacityDocumento4 páginasWhither The Turkish Trading State? A Question of State CapacityGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- How Economic Dependence Could Undermine Europe's Foreign Policy CoherenceDocumento10 páginasHow Economic Dependence Could Undermine Europe's Foreign Policy CoherenceGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Turkey and Russia's Proxy War and The KurdsDocumento4 páginasTurkey and Russia's Proxy War and The KurdsGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Human Resource ManagementDocumento4 páginasIslamic Human Resource ManagementAbdulrahman NogsaneAún no hay calificaciones

- Hamm Roller Hd13 Hd14 h2 01 Electric Hydraulic Diagrams DeenDocumento23 páginasHamm Roller Hd13 Hd14 h2 01 Electric Hydraulic Diagrams Deentroyochoa010903kni100% (57)

- Tanggal Waktu Tema Pembicara Tagline Moderator: Skema Rundown Teacher AcademyDocumento1 páginaTanggal Waktu Tema Pembicara Tagline Moderator: Skema Rundown Teacher AcademyAlainal MafazzaAún no hay calificaciones

- Sayyidatina KhadijahDocumento7 páginasSayyidatina KhadijahNURHIDAYAH BINTI ABDULLAH MoeAún no hay calificaciones

- Absen Kelas XDocumento43 páginasAbsen Kelas Xaphp SMKN 1 BojongpicungAún no hay calificaciones

- A Christian Reads The QuranDocumento46 páginasA Christian Reads The QuranPetcu RalucaAún no hay calificaciones

- Shia Encyclopaedia Chapter 11Documento53 páginasShia Encyclopaedia Chapter 11Imammiyah Hall100% (1)

- Question Paper Class 11 HistoryDocumento2 páginasQuestion Paper Class 11 Historypankhuri1994100% (1)

- 25 Duas From QuranDocumento6 páginas25 Duas From QuranThe Final RevelationAún no hay calificaciones

- Tajikistan Bibliography - Working DraftDocumento27 páginasTajikistan Bibliography - Working DrafteasterncampaignAún no hay calificaciones

- Sufism in Sindh: Past & Present Debate DR Saghar AbroDocumento7 páginasSufism in Sindh: Past & Present Debate DR Saghar AbroSaghar AbroAún no hay calificaciones

- Pakistan in Search of IdentityDocumento149 páginasPakistan in Search of IdentityFahadAún no hay calificaciones

- Dr. Mahdi Abdul Hadi: The Evolution of PalestineDocumento6 páginasDr. Mahdi Abdul Hadi: The Evolution of PalestinekprakashmmAún no hay calificaciones

- Sabean ExchangeDocumento12 páginasSabean ExchangeifriqiyahAún no hay calificaciones

- Refutation To Qadiani Concept of Prophethood - MakashfaDocumento6 páginasRefutation To Qadiani Concept of Prophethood - MakashfaKhateeb Ul Islam QadriAún no hay calificaciones

- Hazrat Mujadid Alf Sani (Sheikh Ahmad SirhindiDocumento5 páginasHazrat Mujadid Alf Sani (Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindiasma abbasAún no hay calificaciones

- Buddhism & Fallacies of Idol WorshipDocumento10 páginasBuddhism & Fallacies of Idol Worshiptruthmyway80470% (1)

- Title 22 Usic 0.2 and 0.3 Volume I. Table of ContenceDocumento5 páginasTitle 22 Usic 0.2 and 0.3 Volume I. Table of ContenceSUPREME TRIBUNAL OF THE JURISAún no hay calificaciones

- Al Khazkhaza (Masturbation)Documento4 páginasAl Khazkhaza (Masturbation)Meesam MujtabaAún no hay calificaciones

- Harris J - You Are My Life LyricsDocumento1 páginaHarris J - You Are My Life LyricsRizky MerliyantiAún no hay calificaciones

- CENTRE FOR HIGH ENERGY PHYSICS M.Sc. Computational Physics (Regular Programme) Admission 2019 GENERAL MERIT LIST (Open MeritDocumento8 páginasCENTRE FOR HIGH ENERGY PHYSICS M.Sc. Computational Physics (Regular Programme) Admission 2019 GENERAL MERIT LIST (Open MeritKhizarAún no hay calificaciones

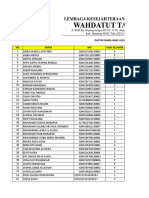

- Data Lksa Wahdatut Tauhid Tahun 2020Documento4 páginasData Lksa Wahdatut Tauhid Tahun 2020AgowGowiFaithWersendAún no hay calificaciones

- TG Iqtf 004082Documento131 páginasTG Iqtf 004082Mbamali Chukwunenye0% (1)

- 4 6026206739718735498 PDFDocumento18 páginas4 6026206739718735498 PDFraj1508Aún no hay calificaciones

- Cultural, Economic, and Political Impact of Islam On EuropeDocumento1 páginaCultural, Economic, and Political Impact of Islam On Europetercac73% (11)