Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

The Old Russian

Cargado por

Steven RendinaDescripción original:

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

The Old Russian

Cargado por

Steven RendinaCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

The Old Russian

from our family camping trips behind the iron curtain in 1961 and 1966

by Steven J Rendina The border. A wide swath of cleared land in the dense northern forest. We had emerged from the foggy Finnish morning. An eerie landscape hidden in the mists that slowly burned away as the sun climbed ever higher. The few other travelers on the road that had passed earlier all had their strong yellow fog lights on so we could spot them coming toward us on the narrow road leading to the USSR. I gazed at the checkpoint in surprise. Nothing in my experience was remotely like this. A few guards armed with Kalashnikov's slung loosely over their shoulders stood by the tiny guardhouse and the black and white striped wooden gate. Looking both to the north and south as far as I could see was a clearing, about 50 yards wide that was the miniature no man's land between Soviet Russia and a freer Finland. On either side were tall trees. Leafy green in the summer. Striking white birches and other hardwoods. Just taller than the tallest trees, at intervals of several hundred feet each all along the clearing stood wooden towers manned by armed guards, protecting the socialist motherland. The guards checked our passports and visas. My family all got out of the VW bus and stood around as questions were asked. Our belongings, packed away in cubbyholes in our camper, custom-designed to sleep six, were thoroughly searched. A small tape recorder was the only item

that drew cautious suspicion from the guards. They put it in a cardboard box and sealed the box, letting us know that we were not to break the seal or remove the recorder while we traveled through the USSR. That was it, the gate lifted, and we were waved through on our way to Leningrad. It was 1966. Leningrad was a beautiful city then. Its many canals and gleaming golden towers made clear its importance in czarist Russia as a waterway to the outside world, the Summer Palace of the czars, old St. Petersburg. We rode on a hydrofoil, a marvel of Soviet engineering that whisked us upriver to the Hermitage. My parents dearly loved trudging my three brothers and I through the great art museums of Europe. This was surely one of the continent's finest. It was in the Hermitage that I was exposed to an art form that moved my restless young soul and made a lasting impression on me. It wasn't the intricately painted icons, but rather one painting in particular that touched my consciousness. I don't even know the great master's name who painted that troublesome work. It was a depiction of St. Sebastian, crucified and shot through and through with arrows. Blood trickling down his slumped corpse. My parents each had rejected religious expression as meaningless. Our home was a stronghold of atheistic thought. Religion was the opiate of the people. A force for ignorance and senseless war. In my life to that point, I had only once visited a synagogue with a friend and once visited a Catholic catechism with another friend. Both experiences had left me with a feeling of awe, of mystery, of something that could not be answered or explained. Here in front of me was a clear demonstration of the power of belief, of faith in something unseen. A man was martyred. We took the desolate highway from Leningrad to Moscow where my father was invited to attend a biochemistry conference, our official reason for the visit to the USSR. Along the way we picked up two hitchhikers. The first was a soldier in uniform. He was friendly in the same way as all Russians we met. Delighted to have met an American family, warm and generous in spirit. He only traveled a short distance with us down the road. The next hitchhiker was an old man. He appeared as a character from a novel. Wrinkled and bent but with eyes that sparkled against the dark backdrop of a life of deprivation and want. There was enough light in his eyes to burn away serious sorrow. All our new Russian friend carried with him was a beige sack. It was half full with small greenish brown pears. It was his nourishment and his capital. Our Russian language skills were minimal. Hello, goodbye, please and thank you. Each of us could count to ten. We repeatedly and joyfully counted to ten with our Russian companion. He communicated mostly by the warmth in his eyes. When this old comrade indicated by gestures that we had reached his destination on the road, my dad pulled over and he climbed out. He hugged each of us and reached into his treasure sack and gave us a couple of dozen of his little pears. Outside Moscow, we camped. The campground was a gathering place of foreign travelers. There were people from all over Europe but most of all we were happy to reconnect with an adventurous band of four young men from Australia. They were taking the summer off to travel through Europe. We had first met them in Norway and then again in Finland. Their freedom and enjoyment of life became my ideal. Here in Russia their panel truck had broken down. It was up on blocks in the campground as they made repairs. Our VW bus also broke down in Moscow and

there were no parts available to make repairs. At a shop in the city an ingenious mechanic, accustomed to working with little, fashioned the needed part form scraps and repaired our engine. Moscow was a vast city. Most people seemed to live in apartment complexes that were springing up everywhere we went. They looked like the urban projects in America's ghettos. Vast governmental productions all in the lackluster style of socialist realism. One night we visited a family that my father had come to know at the conference. We went to their crowded apartment for a festive dinner. My dad and our host toasted each other with much vodka while the rest of us practiced Russian and awaited the meal. In the kitchen, a huge pot of water was boiling for what seemed to me to be hours. We were going to have a real treat - corn on the cob. The corn on the cob in Russia in 1966 for this family was what we in America call field corn. The grain to feed our cattle and pigs so we might increase the yield of meat for our tables. After extensive cooking, the corn was done and made a good part of a satisfactory meal. My delicate stomach and my youngest brother's digestion could not handle the experience. After complaining of severe cramping we both were brought to a local hospital where my stomach was pumped and my mother stayed in the ward on a cot beside us overnight. The hospital was neat, clean, and completely free even to us, foreign travelers. On the way to Kiev we stopped periodically at checkpoints so that our internal travel papers could be examined and approved. Once on that long highway we ran out of fuel. There were no gas stations to be seen. A truck stopped, truckers being the only other travelers allowed on that road. He siphoned gas for us, a common practice, and we were again on our way. In Kiev, we visited some distant relatives of my mother's family. More vodka but no more corn. Everywhere in Russia, the people were so kind, so filled with heart. Our presence brought out such a warm emotional response like the peasant ladies in the Ukraine with their ruddy cheeks and squeals of delight as we used our fancy Polaroid camera to snap pictures of us together. We crossed the great breadbasket of the Soviet Union. My brothers and I pushed back the canvas roof and popped our heads out the top of the VW. We sat on the camper shelf pretending we were engineers driving a train like the Young Pioneers with their red scarves had done at the youth camp we visited. I wanted so badly to be one of them. Endless fields of dazzling sunflowers danced across the vast landscape. We headed west and the sunflower fields eventually did reach their limit. We soon reached the Czechoslovakian border. Once again armed guards questioned our journey and inspected our belongings. To my surprise they did not know about the tape recorder, still sealed in its box.

También podría gustarte

- Black Tea: Shortlisted for the Royal Society of Literature Christopher Bland Award 2020De EverandBlack Tea: Shortlisted for the Royal Society of Literature Christopher Bland Award 2020Aún no hay calificaciones

- Camping with the Communists: The Adventures of an American Family in the Soviet UnionDe EverandCamping with the Communists: The Adventures of an American Family in the Soviet UnionCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (5)

- Jonah and Sarah: Jewish Stories of Russia and AmericaDe EverandJonah and Sarah: Jewish Stories of Russia and AmericaAún no hay calificaciones

- Smashed in the USSR: Fear, Loathing and Vodka on the SteppesDe EverandSmashed in the USSR: Fear, Loathing and Vodka on the SteppesCalificación: 3 de 5 estrellas3/5 (2)

- Siberian Travels: An Oklahoma girl's journey from Moscow to the Sea of JapanDe EverandSiberian Travels: An Oklahoma girl's journey from Moscow to the Sea of JapanAún no hay calificaciones

- Off The Rails: 10,000 km by Bicycle across Russia, Siberia and Mongolia to ChinaDe EverandOff The Rails: 10,000 km by Bicycle across Russia, Siberia and Mongolia to ChinaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (13)

- Black Earth City: When Russia Ran Wild (And So Did We)De EverandBlack Earth City: When Russia Ran Wild (And So Did We)Calificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (32)

- Gadfly in Russia: A Story of Travel, History, People, and PlacesDe EverandGadfly in Russia: A Story of Travel, History, People, and PlacesCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (3)

- Escape into Danger: The True Story of a Kievan Girl in World War IIDe EverandEscape into Danger: The True Story of a Kievan Girl in World War IICalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (3)

- Reeling In Russia: An American Angler In RussiaDe EverandReeling In Russia: An American Angler In RussiaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5)

- The Storks' Nest: Life and Love in the Russian CountrysideDe EverandThe Storks' Nest: Life and Love in the Russian CountrysideCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1)

- How I Became a Man: A Life with Communists, Atheists, and Other Nice PeopleDe EverandHow I Became a Man: A Life with Communists, Atheists, and Other Nice PeopleAún no hay calificaciones

- The Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street: a Russian adventureDe EverandThe Long Song of Tchaikovsky Street: a Russian adventureAún no hay calificaciones

- On the Roads of War: A Soviet Cavalryman on the Eastern FrontDe EverandOn the Roads of War: A Soviet Cavalryman on the Eastern FrontCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (11)

- Moscow Calling: Memoirs of a Foreign CorrespondentDe EverandMoscow Calling: Memoirs of a Foreign CorrespondentCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (4)

- Six red months in Russia: An observers account of Russia before and during the proletarian dictatorshipDe EverandSix red months in Russia: An observers account of Russia before and during the proletarian dictatorshipAún no hay calificaciones

- My First Trip to The Homeland: In Search of Abandoned Treasures Behind the Iron Curtain: Travels with TaniaDe EverandMy First Trip to The Homeland: In Search of Abandoned Treasures Behind the Iron Curtain: Travels with TaniaAún no hay calificaciones

- Red Wave: An American in the Soviet Music UndergroundDe EverandRed Wave: An American in the Soviet Music UndergroundAún no hay calificaciones

- The Humorless Ladies of Border Control: Touring the Punk Underground from Belgrade to UlaanbaatarDe EverandThe Humorless Ladies of Border Control: Touring the Punk Underground from Belgrade to UlaanbaatarCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (8)

- Travels in a Young Country: Discovering Ukraine's Past and PresentDe EverandTravels in a Young Country: Discovering Ukraine's Past and PresentAún no hay calificaciones

- Forgotten Land: Growing Up in the Jewish Pale: Based on the Recollections of Pearl Unikow CooperDe EverandForgotten Land: Growing Up in the Jewish Pale: Based on the Recollections of Pearl Unikow CooperCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (2)

- Love in Defiance of Pain: Ukrainian StoriesDe EverandLove in Defiance of Pain: Ukrainian StoriesAli KinsellaAún no hay calificaciones

- I Visit the Soviets - The Provincial Lady in RussiaDe EverandI Visit the Soviets - The Provincial Lady in RussiaAún no hay calificaciones

- How To Love A Homeland MainDocumento49 páginasHow To Love A Homeland MainOxanaTimofeevaAún no hay calificaciones

- Trapped in 'Black Russia'Letters June-November 1915 by Pierce, RuthDocumento58 páginasTrapped in 'Black Russia'Letters June-November 1915 by Pierce, RuthGutenberg.orgAún no hay calificaciones

- DerailDocumento6 páginasDerailMezey AndrásAún no hay calificaciones

- Memoir Final 6 5 PDFDocumento88 páginasMemoir Final 6 5 PDFJames BlanchardAún no hay calificaciones

- 0 - Fine Tune Your RecoveryDocumento5 páginas0 - Fine Tune Your RecoverySteven RendinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Self Healing FranklinDocumento2 páginasSelf Healing FranklinSteven RendinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Fine Tune/ing Recovery - Addiction Studies InstituteDocumento8 páginasFine Tune/ing Recovery - Addiction Studies InstituteSteven RendinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Fine Tune/ing Recovery - Addiction Studies InstituteDocumento8 páginasFine Tune/ing Recovery - Addiction Studies InstituteSteven RendinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Fine Tuning RecoveryDocumento82 páginasFine Tuning RecoverySteven RendinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Self Healing With Qi Gong ContentDocumento9 páginasSelf Healing With Qi Gong ContentSteven RendinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Fine Tune/ing Recovery - Addiction Studies InstituteDocumento8 páginasFine Tune/ing Recovery - Addiction Studies InstituteSteven RendinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Snake Qigong Workshop Teaches Ancient Exercises for Strength, Transformation & Nature WisdomDocumento8 páginasSnake Qigong Workshop Teaches Ancient Exercises for Strength, Transformation & Nature WisdomSteven RendinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Harvard Taichi BenefitsDocumento5 páginasHarvard Taichi BenefitsSteven Rendina100% (1)

- Foundations Three TuningsDocumento10 páginasFoundations Three TuningsSteven Rendina100% (1)

- Guidelines On Occupational Safety and Health in Construction, Operation and Maintenance of Biogas Plant 2016Documento76 páginasGuidelines On Occupational Safety and Health in Construction, Operation and Maintenance of Biogas Plant 2016kofafa100% (1)

- #3011 Luindor PDFDocumento38 páginas#3011 Luindor PDFcdouglasmartins100% (1)

- Personalised MedicineDocumento25 páginasPersonalised MedicineRevanti MukherjeeAún no hay calificaciones

- John Hay People's Alternative Coalition Vs Lim - 119775 - October 24, 2003 - JDocumento12 páginasJohn Hay People's Alternative Coalition Vs Lim - 119775 - October 24, 2003 - JFrances Ann TevesAún no hay calificaciones

- Riddles For KidsDocumento15 páginasRiddles For KidsAmin Reza100% (8)

- GIS Multi-Criteria Analysis by Ordered Weighted Averaging (OWA) : Toward An Integrated Citrus Management StrategyDocumento17 páginasGIS Multi-Criteria Analysis by Ordered Weighted Averaging (OWA) : Toward An Integrated Citrus Management StrategyJames DeanAún no hay calificaciones

- AZ-900T00 Microsoft Azure Fundamentals-01Documento21 páginasAZ-900T00 Microsoft Azure Fundamentals-01MgminLukaLayAún no hay calificaciones

- Bharhut Stupa Toraa Architectural SplenDocumento65 páginasBharhut Stupa Toraa Architectural Splenအသွ်င္ ေကသရAún no hay calificaciones

- SQL Guide AdvancedDocumento26 páginasSQL Guide AdvancedRustik2020Aún no hay calificaciones

- Petty Cash Vouchers:: Accountability Accounted ForDocumento3 páginasPetty Cash Vouchers:: Accountability Accounted ForCrizhae OconAún no hay calificaciones

- Intro To Gas DynamicsDocumento8 páginasIntro To Gas DynamicsMSK65Aún no hay calificaciones

- Sanhs Ipcrf TemplateDocumento20 páginasSanhs Ipcrf TemplateStephen GimoteaAún no hay calificaciones

- RACI Matrix: Phase 1 - Initiaton/Set UpDocumento3 páginasRACI Matrix: Phase 1 - Initiaton/Set UpHarshpreet BhatiaAún no hay calificaciones

- ESA Knowlage Sharing - Update (Autosaved)Documento20 páginasESA Knowlage Sharing - Update (Autosaved)yared BerhanuAún no hay calificaciones

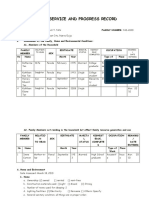

- Family Service and Progress Record: Daughter SeptemberDocumento29 páginasFamily Service and Progress Record: Daughter SeptemberKathleen Kae Carmona TanAún no hay calificaciones

- C6030 BrochureDocumento2 páginasC6030 Brochureibraheem aboyadakAún no hay calificaciones

- Polytechnic University Management Services ExamDocumento16 páginasPolytechnic University Management Services ExamBeverlene BatiAún no hay calificaciones

- FX15Documento32 páginasFX15Jeferson MarceloAún no hay calificaciones

- PESO Online Explosives-Returns SystemDocumento1 páginaPESO Online Explosives-Returns Systemgirinandini0% (1)

- Decision Maths 1 AlgorithmsDocumento7 páginasDecision Maths 1 AlgorithmsNurul HafiqahAún no hay calificaciones

- Archlinux 之 之 之 之 Lmap 攻 略 ( 攻 略 ( 攻 略 ( 攻 略 ( 1 、 环 境 准 备 ) 、 环 境 准 备 ) 、 环 境 准 备 ) 、 环 境 准 备 )Documento16 páginasArchlinux 之 之 之 之 Lmap 攻 略 ( 攻 略 ( 攻 略 ( 攻 略 ( 1 、 环 境 准 备 ) 、 环 境 准 备 ) 、 环 境 准 备 ) 、 环 境 准 备 )Goh Ka WeeAún no hay calificaciones

- Artist Biography: Igor Stravinsky Was One of Music's Truly Epochal Innovators No Other Composer of TheDocumento2 páginasArtist Biography: Igor Stravinsky Was One of Music's Truly Epochal Innovators No Other Composer of TheUy YuiAún no hay calificaciones

- Mission Ac Saad Test - 01 QP FinalDocumento12 páginasMission Ac Saad Test - 01 QP FinalarunAún no hay calificaciones

- C6 RS6 Engine Wiring DiagramsDocumento30 páginasC6 RS6 Engine Wiring DiagramsArtur Arturowski100% (3)

- Pre Job Hazard Analysis (PJHADocumento2 páginasPre Job Hazard Analysis (PJHAjumaliAún no hay calificaciones

- Pub - Essentials of Nuclear Medicine Imaging 5th Edition PDFDocumento584 páginasPub - Essentials of Nuclear Medicine Imaging 5th Edition PDFNick Lariccia100% (1)

- Mercedes BenzDocumento56 páginasMercedes BenzRoland Joldis100% (1)

- Service and Maintenance Manual: Models 600A 600AJDocumento342 páginasService and Maintenance Manual: Models 600A 600AJHari Hara SuthanAún no hay calificaciones

- Book Networks An Introduction by Mark NewmanDocumento394 páginasBook Networks An Introduction by Mark NewmanKhondokar Al MominAún no hay calificaciones

- DLP in Health 4Documento15 páginasDLP in Health 4Nina Claire Bustamante100% (1)