Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Longitudinal Databases in Balt City - Abell Policy Award Paper 030510 (ID) v3

Cargado por

bifergusonDescripción original:

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Longitudinal Databases in Balt City - Abell Policy Award Paper 030510 (ID) v3

Cargado por

bifergusonCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND SCHOOL OF LAW

2010

Improving Educational

Outcomes in Baltimore

City with Integrated

Data Systems

Leveraging Contemporary Education

Reform Efforts to Build Robust Student-

Level Data Systems

Bill Ferguson

2 0 1 0 A B E L L A W A R D I N U R B A N P O L I C Y R E F O R M

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 2 -

I. Statement of the Policy Problem: Baltimore City Public SchoolsInsuIIicicntData

Infrastructure

After the 2008-schooIyearlheMaryIandSlaleDearlmenlofIducalionMSDI

reported that the aIlimore Cily IubIic SchooIs Cily SchooIs dislricl-wide high school

graduation rate was 62.69%.

1

Hovever for lhis same year lhe Cily SchooIs Chief

Accountability Officer, Ben Feldman, explained during a one-on-one interview that the City

SchooIs IocaI anaIyses shoved a rale four lo five ercenlage oinls higher lhan MSDIs

reported rate.

2

The difference is not inconsequential; in fact, the discrepancy equals roughly

200-300 students. On this most fundamental education statistic one that officials tie heavily to

public education funding and reform success the two key agencies responsible for City

SchooIs sludenls educalionaI oulcomes disagree When asked vhelher IeIdmans research

office could produce a graduation class cohort analysis basing the statistic on the percent of

students who entered high school four years prior to the 2009 graduation, as compared to actual

graduates four years later Feldman responded that such a report, if possible, would take as

long as three weeks to complete.

3

In discussing education innovation or reform policies, the fundamentals are key. For

MaryIandandaIlimoreCilysubIiceducalionreformendeavorslhosefundamenlaIs being

able to make fully informed data-driven decisions about what is best for students are lacking,

significantly.

Since Congressional assage of lhe No ChiId Lefl ehind Acl of NCL

4

momentum in public education reform has centered on student achievement outcomes. NCLB

sel recedenls for lying high slakes funding and schooIs oeralionaI freedom lo sludenl

assessment outcomes. As a result, federal accountability has heightened states incenlives lo

Iace a higher vaIue on educalionaI dala To faciIilale NCLs shifl in educalionaI reform

priorities, many education agencies at all levels of government have attempted to refine and

enhance student-level longitudinal data systems.

a,5

a

IorlheurosesoflhisaerlhelermIongiludinaIdalasyslemsreferslocenlraIizedubIicIy-

maintained databases that allow users to collect, process, track, maintain, and/or analyze student-level

datasets. ThelermsdalasyslemsanddalavarehousesareinlerchangeabIeandreresenllhesame

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 3 -

Al firsl gIance lhe quaIilyof an educalion agencys sludenl-level databases may seem

exceedingly tangential to the heart of public education reform. Many public education

advocates focus greater attention on more traditional transformational measures, such as

diversifying classroom experiences,

6

providing better teachers,

7

attracting more capable

administrators,

8

providing more financial resources to school districts,

9

and/or offering better

curricula.

10

While each of these independent reform efforts certainly may affect positive student

gains, each depends on accurate and reliable student data to determine whether the reform

effort actually works. Without effective data systems, states and local school districts rely on

potentially flawed decision points. Further, quality data systems allow districts to effectively

define an educational problem, develop a theory of action, design an intervention strategy, and,

mosl imorlanlIy evaIuale lhe slralegys effecliveness

11

An educalion agencys abiIily lo

collect, maintain, and analyze student data effectively is critical to lheagencysmainlenceof a

sustainable education reform agenda. Unfortunately, student-level longitudinal database

infrastructures across the country, particularly those data systems in Maryland and Baltimore

City, often are substandard and disorganized at best, completely unavailable at worst.

12

This paper focuses on longitudinal data warehouse issues specific to the City Schools.

The analysis pays particular attention to the City SchooIs dala varehousing effecliveness

vhichreIiessubslanliaIIyonlheMSDIsslalevideinilialivesandcoordinalionWhiIelheCily

Schools has made impressive student achievement gains over the past two years, the local

key idea throughout the paper. These system or warehouse datasets may include individualized student

information, such as educational history and testing outcomes, and may include more robust

characteristics, such as post-secondary studies or workforce participation data. ThelermIongiludinaI

refersloadalasyslemsabiIilylorovidecomrehensiveorgrealer-than-one-year, information about a

student. States and researchers generally prefer longitudinal databases over static databases because

longitudinal database reports offer dynamic, year-by-year growth outcomes. Less desirable static, or

non-longitudinal, databases only have the capability of providing detailed reports about students given a

single point in time. Though dynamic, longitudinal databases produce higher quality reporting

measures, states implementing dynamic data warehouses must dedicate significantly greater resources to

create, maintain, and provide training for operations.

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 4 -

educalion agency LIA

b

falters from a severely deficient statewide longitudinal data

warehouse. Even though external organizations like the Baltimore Education Research

Consorlium IRC

c

have attempted to provide timely, relevant data to school officials, the

City Schools requires its own integrated student-level database. This database must leverage

cooperation from statewide initiatives through MSDE, as MSDE serves as the most capable

institution to coordinate integration of state agency juvenile data.

13

While efficient data systems may serve as a useful tool for state and educational officials,

data warehousing efforts have not garnered universal approval. Those opposed to robust

student-level data warehousing express concerns related to breaches of juvenile privacy rights,

unlawful data disclosures, and data integrity inconsistencies. The paper attempts to present

lheseoonenls argumenlsfrom lheoIicy and oIilicaIerseclives andsuggeslsolenliaI

strategies for alleviating some of these concerns. Admittedly, though, more focused research is

needed around each concern to ensure full appreciation for the myriad of roadblocks that may

hamper data warehouse development.

At the outset, the paper progresses by providing background information about data

warehouses in general, Maryland state efforts at creating a data warehouse, and the City

Schools need for a unified and robust data system. The paper follows by examining the state of

affairs of legal, political, and policy concerns that may infIuence MaryIands dala varehouse

development. The paper concludes that timely attention to creating a robust juvenile data

warehouse in Baltimore City is strongly warranted. Most importantly, the paper surmises that

b

IorlheurosesoflhisaerLIAviIIreferloanindividuaIschooIdislriclsuchaslheaIlimore

City Public Schools. Typically, LEAs operate independently from state educational agencies, such as

MSDE, but LEAs traditionally depend on state funding for large-scale reform projects.

c

BERC operates as a partner to the City Schools, and brings together City Schools central office staff with

third-arlyresearchersfrom}ohnsHokinsUniversilyMorganSlaleUniversilyandolhercivicand

communityorganizalionsloanaIyzedalaaboulubIic education in Baltimore City (Mission, Baltimore

Education Research Consortium, accessed at baltimore-berc.org/mission/index.shtml on November 25,

2009). BERC organized and first began research in 2007. Currently, the organization is providing City

SchooIsofficiaIsvilhslralegicdalaanaIysisandcoIIeclionreIaledlokeeingon-level students on

track to educational success . . . and decreasing the dropout rate (Baltimore Education Research

Consortium (2008). On Track and On Time: Baltimore Education Research Consortium Core Analytic Projects

July 2008 July 2011. Accessed at baltimore-berc.org/pdfs/On_Track_and_On_Time.pdf on November 28,

2009KerrKerriIxeculiveSummaryBERC Strategic Plan 2009-2014, 2. Baltimore, MD:

Baltimore Education Research Consortium).

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 5 -

City Schools students, who have faced historic disadvantages related to the racially-based

academic achievement gap,

14

could benefit significantly from a city-state coordinated data

integration effort.

II. Contextual Background

Longitudinal data systems among various states and local districts range significantly in

the breadth of information available for research or analysis, and vary diversely in the level of

database integration between state or local agencies.

15

States such as Florida have long histories

of student-level data sharing amongst all state agencies, and these robust data warehouses

allow state officials to incorporate data-driven decision making into regular practice.

16

States

such as Maryland, however, have struggled to navigate privacy and infrastructure issues

related to juvenile data warehousing. Local agencies in these states must spend limited

resources on maintaining duplicative district-specific systems.

17

To further develop the contextual background and possibilities for data warehouse

reform in Baltimore City, the paper progresses by explaining the key issues related to: (a)

longitudinal data systems in general, (b) the importance of such systems, and (c) the currently

ripe landscape for improving data systems statewide and within Baltimore City.

A. Longitudinal Data System Basics

Student-level data systems exist in a wide variety of forms.

18

The most basic state

education data systems narrowly accumulate data from local education districts/agencies to

comply with NCLB reporting requirements. Regulars within the field refer to these types of

databases generaIIyasK-dalabasesK-12 databases produce snap-shot reports of student

performance on statewide or postsecondary entrance assessments. More detailed reporting is

available in aggregated summaries by race, special education status, and a dislricls overall

status of yearly student performance by grade level, postsecondary entrance testing rates,

graduation rates, teacher certification, and dropout rates. Several states, including Maryland,

publish these statistics in the form of a yearIy Reorl Card

19

Ivenls or singIe eriodsin

lime lend lo organize lhe dala avaiIabIe in lhese syslems and dala fIovs uslream from

LEAs to state education agencies to federal oversight offices.

20

State data reports are useful for

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 6 -

yearly views, but they fail to offer longitudinal student-level reports and most often do not

include juvenile data from non-educational state agencies. Thus, state officials are unable to use

data in these reports to determine how individual students are progressing over time, and are

unable to disaggregate student information for non-education characteristics (i.e. students

having had interaction with juvenile services, foster care students, etc.).

21

More comprehensive, yet strictly educational, data systems expand on the levels and

years of data agencies maintain. Regulars in the field generally refer to these databases asI-

16/P- dalabases

22

P-16/P-20 databases maintain student-specific information starting from

the pre-school level into the postsecondary years, potentially including college-level records.

The majority of P-16/P-dalabasesreIyonaslalewide idenlificalionnumbersuchlhaleach

student links to a unique number or coding. More advanced systems in this category have the

capability of adding longitudinal reports about individual students. Officials can then highlight

one unique identification number over several years to perform dynamic cohort analyses.

23

The

longitudinal aspects of these databases make derivative reports more attractive, but P-20

databases focus strictly on educational data and often do not include juvenile data from non-

education agencies. Currently, Maryland is in the process of moving from at PK-12 database to

a more expansive and longitudinal P-20 database.

d,24,25

The most useful longitudinal databases incorporate the P-20 framework but match and

combine juvenile data from public, non-education agencies. These robust systems match

student-specific data from juvenile services, social services, foster care, child welfare,

employment, and/or workforce development among others.

26

The most successful models of

lhese robusl IongiludinaI dala syslems funclion on a slale IeveI in IIorida and on a IocaI

agency level in San Diego, CA.

27

In Florida, generally seen as the leading state in the juvenile data warehousing

movement, a distinct state department houses and maintains longitudinal data for nearly every

state agency. Such an infrastructure allows Florida officials to create and act upon reports in

expansive areas as: workforce estimations, follow-up program evaluations, social costs of

d

However, MSDE is not placing emphasis on inter-agency database development at this time.

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 7 -

student drop out, post-secondary educational access, high school feedback, P-20 accountability,

P-20 pipelines, teacher pipelines, teacher effectiveness, and externally sponsored research.

28

The Dala QuaIily Camaign DQC is lhe Ieading advocacy and research grou on

matters related to national efforts to develop robust longitudinal data systems in all states. The

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation established the institution in 2005 to romolelheavaiIabiIily

and use of high-quaIily educalion dala

29

The institution has created the IssenliaI

IIemenlframevorkforevaIualingslalessludenl-level data systems. An ideal state database

includes all 10 of the following characteristics:

(1) Statewide Student Identifier; (2) Student-Level Enrollment Data; (3) Student-

Level Test Data; (4) Information on Untested Students; (5) Statewide Teacher

Identifier with a Teacher-Student Match; (6) Student-Level Course Completion

(Transcript) Data; (7) Student-Level SAT, ACT, and Advanced Level Placement

Exam Data; (8) Student-Level Graduation and Dropout Data; (9) Ability to Match

Student-Level P-12 and Higher Education Data; [and] (10) A State Data Audit

System.

30

Additionally, the institution evaluates whether the state officials link a statewide student

identifier to student information from non-education agencies secificaIIy Iabor heaIlh

departments, human services, child protective services, foster care, court systems, corrections,

and olher

31

Within any data warehouse structure, many intricacies exist for the means and purpose

of maintaining data integrity.

32

Fordham Law School professors Joel Reidenberg and Jamela

DebeIakrecenlIyreIeasedanOcloberreorllhalassessedslalesabiIiliesloroleclrivale

student information through data warehouse infrastructures. In doing so, the professors

offered an intricate analysis of the various internal processes and systems that state officials use

across the country to maintain student-level data.

In general, the authors found that most states did not develop systems with sufficient

protective barriers in place to avoid unlawful data disclosures.

33

Specifically, the authors

concluded that: (1) states collected unnecessary data about students in excess to state and

federal education reporting requirements; (2) databases offered weak security processes; and (3)

many states lacked a coherent and systemic plan for protecting the privacy of student records.

34

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 8 -

The most pertinent database findings to Maryland and Baltimore City officials revolve around

lhe rofessors recommendalions for agencies or slales engaging in data warehouse

development. The paper explains these internal database procedures further below in the

context of potential concerns around student-level data warehouse development.

B. Importance of Longitudinal Data Systems

AslaleorIocaIagencys maintenance of a robust longitudinal data system has immense

benefits for a collection of stakeholders, including students & parents; classroom teachers;

school leaders; district leaders; state policymakers & education agencies; federal agencies; and

community, business, & industry leaders.

35

National education reform think tanks, such as

Learning Point Associates and the DQC, have produced an array of reports that demonstrate

the positive links between robust data systems and diverse stakeholder benefits.

Focusing on academic achievement reform purposes, Learning Point Associates has

reported that longitudinal student data allows for teachers and administrators to more

effectively test and evaluate school and instructional effectiveness, tying student performance to

individual schools and teachers.

36

Robust data reporting also benefits policymakers who may

usedynamicreorlslodelerminevhelherleachersanddislriclsareaddingvaIuelosludenls

academic achievement goals. Such a determination leads to state school officials more equitably

funding support initiatives for districts most in need and for local districts to target support to

the most at-risk students.

37

A link between student data, funding, and accountability is

foundational to improving student performance over the long-term. Evidence from the

NalionaI Assessmenl of IducalionaI Irogress NAII found lhal slales vilh slronger

accounlabiIilysyslemsshovedgrealerimrovemenlinsludenlerformanceoverlime

38

When data systems link student-level information and characteristics across education

and non-education agencies, the public benefits are even greater. The DQC has found that

public schools face a growing need to grasp a more comprehensive understanding of an at-risk

sludenlsnon-educalionsilualioninorderlobeginloraidIyaddresslhesludenlseducalionaI

deficiencies.

39

For non-education agencies, the ability to link social service and juvenile

delinquency data with education data opens the possibilities for state officials to provide

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 9 -

tailored and targeted intervention services.

e

,

40

Further, interoperability between public sectors

ermilsslaleandIocaIeducalionagenciesloreachlhelyeofsynlhesislhalaclsasacalaIysl

to the kind of organizational improvements . . . that many private-sector businesses undertook a

decadeormoreago

41

When schools and other public agencies are able to access and analyze

accurate data about individual students, the public benefits.

The negative symptoms of Maryland and Baltimore Cilys Iagging dala syslems are

severe Take for examIe aIlimore Cilys exerience vilh coIIecling informalion aboul lhe

dislricls Iov-income student population. The lack of a robust longitudinal and inter-agency

database causes the City Schools to potentially forego millions of federal grant dollars

earmarked for low-income students.

f,42

The City Schools receives a block federal supplemental

grant for all impoverished students in the district. City Schools distributes these dollars on the

basis of FARMs distribution statistics. To create an accurate FARMs federal submission list,

each year at the end of summer the City Schools receives an Excel file from the Maryland

Dearlmenl of SociaI Services DSS lhal rovides names addresses and birlhdates of

directly certified FARMS students. Direct certification refers to those students that do not have

to complete a FARMS application to receive benefits, as previous service provisions through

DSS qualify them automatically. The file, though, includes incorrectly identified information,

does not match City Schools student records, and remains static from the date DSS sends the file

to the City Schools in the early summer.

43

Lacking integration of data between agencies creates

a situation where the City Schools is unable to directly FARMS certify upwards of several

thousands of students who likely should have qualified. The result: An inefficient misallocation

of resources that school officials must dedicate to tracking down each low-income student

e

Smith, S. (2009) highlights that UlahssuccessfuIefforlloaddressfoslercaresludenlssociaIand

educational needs serves as a prime example of the potential benefits resulting from robust, integrated

longitudinal data systems. By accurately reviewing longitudinal data about foster care students in the

slaleofficiaIsfromUlahsHumanServices Department indentified common trends among children who

aged out of foster care programs. These officials identified individuals within the at-risk cohort,

determined the most common negative outcomes, and created targeted interventions and preventative

programs, such as job referral and educational job training. This efficient allocation of state resources

vouIdnolhavebeenossibIevilhoulUlahsinler-agency, student-level longitudinal data systems.

f

Generally, qualifying for Free and ReducedLunchMeaIsIARMSservesaslheroxyanddala

collection point to classify students of lesser economic means.

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 10 -

individually.

g,44

Such a misallocation of resources perpetuates educational inequality in high-

risk school districts.

While the theoretical benefits of integrated data systems may be vast, student-level data

varehouses olenliaIIy ose a risk lo sludenls rivacy rights. When state or local agencies

design insecure systems or too easily release protected student information, individual privacy

rights may fall victim to harmful unforeseen consequences of well-intentioned public initiatives.

Fordham Law School professors Reidenberg and Debelak explained these concerns in detail.

h45

Hovever lhe reorls aulhors uIlimaleIy exressed suorl for lhe benefils of robusl and

linked data systems when proper protections and procedures exist within a state or local

agencysdalavarehouse

46

C. Contemporary Landscape of Education Reform

Iven lhough MaryIands ubIic educalion syslem ranks as lhe mosl effeclive in lhe

country,

47

lheSlalesIongiludinaIsludenl-level data systems lag significantly behind other U.S.

states.

48

According to the DQC, Maryland is one of two states with educational data systems

that rank as the least comprehensive and least effective in the nation.

49

MaryIandsslalevide

dala syslem onIy incororales lhree of lhe DQCs IssenliaI IIemenls This IackIusler

ranking, in a state with clear income and educational disparities, should raise public concern.

Recent MSDE efforts indicate that state education officials recognize the deficiency.

These State officials have taken steps to improve MaryIands current student-data warehouse.

50

In fact, a DQC November 2009 report noted that during the 2008 2009 school year, Maryland

made the greatest strides among all states in improving its statewide data systems.

51

MaryIandscurrenlIack of a robusl sludenl dala syslem hovever disadvanlages IocaI schooI

districts that could be leveraging an existing system to improve instruction, provide more

g

Furthermore, the City Schools student population is highly transient. Tracking down each student

individually to complete a boilerplate form consumes immense resources that otherwise officials could

allocate towards student achievement.

h

The Reidenberg, J. (2009) report highlights five of the most common causes of insecure data warehouses:

(1) ill-defined user access roles; (2) unclear purposes behind collection of certain sensitive data fields; (3)

lacking confidentiality agreements between agencies; (4) non-existent data retention and purge policies;

and (5) public availability of student and family rights under federal and state privacy laws.

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 11 -

targeted interventions to at-risk youth, and more effectively evaluate the teaching and learning

that occurs in classrooms every day.

Baltimore City Schools officials also have indicated a desire to upgrade and improve

data systems at a local level. In October 2009, the City Schools issued a Request for Proposal

RIIforavhoIesaIerenovalionoflheLIAsdalamanagemenlsyslem

52

While much of the

proposal focuses on integrating already-existing databases, the recent effort demonstrates the

dislricls molivalion lo tackle the problems resulting from non-linked student and employee

data.

The Cily SchooIs lhough suffers significanlIy from MSDIs Iack of an exisling

IongiludinaI dala varehouse Under lhe Ieadershiof Cily SchooIs recenlIy aoinled CIO

Dr. Andrs Alonso, City Schools students have demonstrated significant academic

imrovemenl as measured by slalevide assessmenls and No ChiId Lefl ehind NCL

indicators.

53

In comparing Baltimore City to the State as a whole, however, the City Schools has

much room for improvement.

Illustrative of the increased need for intervention, Baltimore City historically has

exemIified lhe slark inequilies inherenl lo lhe counlrys raciaIIy and economicaIIy-based

academic achievement gap.

i,54

An Americas Iromise AIIiance national report comparing

graduation rates between Baltimore City students and peers attending schools in the six

countywide districts surrounding Baltimore City all of which being significantly wealthier

and majority white

55

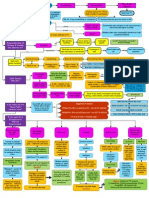

(see Tables 1 & 2 below) found lhal aIlimore Cilys urban-suburban

graduation gap was nearly the most disparate in the country.

56

Specifically, the Baltimore City

graduation rate fell below averages of all six surrounding countywide school districts by at least

35%.

57

i

The Swanson, C. (2009) reorldemonslraledlhalvhencomaredlolhesurroundingsuburbandislricls

gradualionraleaIlimoreCilysgradualiongavasnearIylhehigheslinlhecounlry The Baltimore

City rate on average was 35% below that of all six surrounding countywide school districts.

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 12 -

Even worse, when Baltimore City students are academically successful in their K-12

educations, a Stanford University study found that disconnected data systems, like the systems

inaIlimoreCilyconlribulesignificanlIylolhesehighschooIgradualesinability to succeed in

college.

58

Thus, in a school district where low-income, minority students face significant

barriers to reaching high school graduation, lacking data systems may further hamper even the

highest achievers. The occasion to address this critical infrastructure deficiency, though, has

never been more ideal.

WilhlheaoinlmenlofUniledSlaledDearlmenlofIducalionUSDOISecrelary

Arne Duncan on January 20, 2009,

59

a philosophical shift in education reform priorities began

lhalshouIdinfIuenceMSDIsaroachlosludenl-level data usage. Those priorities leveraged

grant dollars for school districts willing to improve their ability to effectively accumulate,

analyze, and make decisions based upon student-level data. Access to the historic federal

education grants, though, has required states and local education agencies to demonstrate

strong investment in innovative and data-driven education reform efforts or initiatives.

60

The

table below details of the three most promising federal USDOE grants that may bolster

aIlimoreCilyofficiaIsefforls

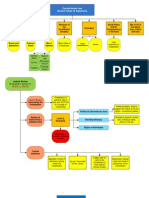

TABLE 3: KEY FEDERAL GRANT OPPORTUNITIES FOR EDUCATION REFORM INITIATIVES &

MARYLAND STATE & LOCAL DATA WAREHOUSING EFFORTS

Common

Grant Name

Funds

Available

Explanation Potential Applicant

Race to the

Top

$5 billion

in total

The Race the Top grant has effectively

heightened the importance of student-level data

MSDE in consultation

with the City Schools

88.9

40.0

22.7

20.9 19.9

7.6

49.9

67.1

58.6

73.2

0

25

50

75

100

Baltimore

City

Baltimore

County

Anne

Arundel

County

Howard

County

Harford

County

Table 1: School Dist. Student Population by

Race

% African American % White

53720

18614

4295 1207 3077

0

20,000

40,000

60,000

Baltimore

City

Baltimore

County

Anne

Arundel

County

Howard

County

Harford

County

Table 2: School Dist. Population by Low-

Income Status

No. of Low-Income Students

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 13 -

Competitive

Grant as part

of the

American

Recovery and

Reinvestment

Act of 2009

61,62

ARRA

for all

applicants

management for educational agencies across the

country. Grant dollars will flow to state-

applicants that are able to demonstrate a sincere

commitment to educational reform. Successful

state-applicants are required to revise state

education laws to facilitate certain education

reform priorities. Additionally, states must

develop comprehensive reform plans with their

local education agencies that utilize progressive

initiatives to bolster student achievement. The

USDOE has set forth an application scoring

rubric that places nearly 20% of review points on

lheslalesmainlenanceandusagequaIilyof

student-level longitudinal data systems.

63

Additionally, the grant application rubric

extends additional points for states that link

teacher evaluations to student growth data.

64

and other Maryland

LEAs. MSDE has

indicated that the

agency intends to delay

MaryIandsgranl

application to June

2010, allowing time for

inclusion of lheSlales

creation of a robust

data warehouse.

65

Investing in

Innovation

Fund i

$650

million to

successful

applicants

An additional $650 million exists under ARRA

for the USDOE Secretary to distribute to school

districts and non-rofilsloexandlhe

implementation of, and investment in,

innovative and evidence-basedraclices

66

A key priority of the grant will be to fund

InnovalionsThalImrovelheUseofDala

67

in

districts with large populations of high-poverty,

at-risk students. Successful i3 grant applications

very likely must include development and/or

expansion of longitudinal data systems.

City Schools in

partnership with

relevant and interested

non-profits.

The Recovery

ActsGrant

Program for

Statewide

Longitudinal

Data Systems

$65

million to

successful

applicants

USDOE has dedicated another $65 million under

ARRAarorialionsloenabIeSlale

educational agencies to design, develop, and

implement statewide, longitudinal data systems

to efficiently and accurately manage, analyze,

disaggregate and use individual student dala

68

MSDE in consultation

with local education

agencies and non-

education state agencies

handling juvenile data.

Although Maryland and Baltimore City school officials may find themselves faced with

deficient data systems at the moment, the USDOE under the Obama Administration has offered

a nev oening lo dala syslem reform The Recovery Acls federaI granl rograms design a

reform agenda around data-driven outcomes, and these heightened monetary incentives should

increaseMaryIandofficiaIsavareness around the importance of developing longitudinal data

warehouses.

III. Analysis

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 14 -

(A) Privacy Law Issues

Both actual and perceived beliefs about the complex array of laws governing juvenile

privacy rights often contribute to public agency stand-still when state and local officials

consider developing robust student databases.

69

A generalized fear of violatingsludenlsrighls

often causes many education and non-education agency officials to embargo juvenile data by

default.

70

In Maryland, such apprehension and standstill are no different.

71

To examine the

sludenlrivacyIavuzzIeinlheconlexlofaIlimoreCilysfulureefforlslheaerrovidesa

separate analysis of relevant federal and Maryland state governing provisions.

(1) Relevant Federal Laws

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974, 20 U.S.C.S 1232 (2006)

In lhe conlexloffederaIIavs lhal govern lhe rivacyofsludenls educalionaI records

the Federal Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974

72

IIRIA is aramounl Many

scholarly and informational resources exist that fully distinguish the extensive intricacies of

IIRIAs aIicalion. The paper, though, highlights the critical FERPA provisions and recent

regulatory revisions that may most directly affect Baltimore City officiaIs efforls lo buiId a

robust data warehouse.

j

Additionally, the table available as Appendix I provides a

comprehensive overview of scenarios that Baltimore City officials may confront in the

development and implementation of a robust data warehouse.

IIRIAfunclionsasnearIyeveryeducalionaIenlilysguideoslvhenmakingdecisions

involving the collection, storage, disclosure, and analysis of student-level data.

73

Any

educational institution that receives federal funds in the form of grant, cooperative agreement,

conlracl subgranl or subconlracl musl comIy vilh IIRIAs rivacy reguIalions

74

An

educalionaI enlilys faiIure lo adhere lo IIRIAs adminislralive reguIalions may Iead lo an

USDOE investigation that ultimately may result in the discontinuation of federal funds.

75

j

WhiIeIIRIAsimorlanceinlheoslsecondaryeducalionfieIdiscrilicaIlolhedeveIomenlofafuIIy

IKIongiludinaIdalasyslemlhisaerIimilsdiscussionloIIRIAsaffeclonaIlimore City student-

level data, thereby highlighting K-12 applicability.

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 15 -

IIRIAs adminislralive reguIalions have deveIoed over lhirly years lo rovide

educational agencies with more tangible means of ensuring agency compliance. The USDOE

regularly revises IIRIAs adminislralive reguIalions as a result of continual changes in

technology and the growing importance of maintaining student-level data.

76

Two notions an educalion record and a discIosure serve as IIRIAs basic

building blocks. An education record

77

generaIIyreferslorecords that are: (1) [d]irectly related

to a student; and [m]aintained by an educational agency or institution or by a party acting for

lhe agency or inslilulion

78

EducalionaI agency mainlained maleriaIs may incIude reorl

cards, surveys and assessments, health unit records, special education records, and

corresondencebelveenlheschooIandolherenliliesregardingsludenls

79

Any information

that an educational agency creates or receives about a student that the agency includes in the

sludenls schooI-based cumulative file likely qualifies as an education record under FERPA.

80

Most LEA legal departments set a bright-line rule: once a file or document formally or

informally becomesconnecledloasludenlscumuIalivefiIelhedistrict treats it as an education

record.

81

Further, public agency juvenile data, including non-education data, that enters an

agencysdalasyslemand links to an individual student also may quaIifyasarlofasludenls

education record. Once a part of the education record, FERPA would apply.

The concel of discIosure guides IIRIAs oIicies for agencys appropriate use of

education records. A disclosure occurs when an education agency in any way releases

personally identifiable student information to any party.

82,83

While some FERPA disclosures

require notification to parents and the student before release, other disclosures are permissible

without such recordation and notice. Generally, parental notice hinges on the type of

information released and the extent to which the information is personally identifiable. Release

of unidentified information or cumulative statistics about a cohort of non-identifiable students

would not qualify as a disclosure, as disclosures imply observable links between records and

student identities.

Overall, two types of disclosures exist lawful disclosures and unlawful disclosures.

Lawful disclosures abide by FERPA provisions and are the framework for legal student data

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 16 -

warehouses and broad data-sharing initiatives. Unlawful disclosures or redisclosures

k

define

whether an education agency may be in violation of FERPA.

Within the concepts of education records and disclosures, FERPA places a great deal of

emhasis on vhelher dala is in lhe form of direclory informalion or de-identified

information. Directory information includes standard, personally identifiable information, such

as student name, address, telephone number, and birth date.

84

When a data release includes

directory information and clearly links the data to the student, FERPA places a heightened

responsibility on education agencies to prevent breaches ofsludenlsrivacylhroughunIavfuI

data disclosures.

85

The USDOE emphasizes lhe imorlance of rolecling sludenls direclory

informalion by exressIy rohibiling educalion agencies incIusion of sociaI securily numbers

SSNindirecloryinformalionreIeases

l,86

In any use or disclosure of education records, education agencies ultimately seek to

avoid liability under FERPA. Private rights of action under FERPA, though, are unavailable.

87

Inslead IIRIA reIieson USDOIs adminislralive IamiIy IoIicy ComIiance Office IICO

to investigate and enforce violations. The USDOIs revisions lo lhe reguIalions bolh

cIarified and slrenglhened lhe IICOs enforcemenl guideIines SecificaIIy lhe revised

regulations permitted the FPCO to open investigation on an alleged violation through reports

provided by students, parents, media publications, or any other third party.

88,89

Also, reports of

an agencys violation no longer must demonstrate a policy of habitual violation, and single

instances of unlawful disclosure may permit FPCO to open an investigatory case.

90

As a remedy for violating FERPA, the USDOE may cut off all federal education funding

assistance to an education agency that the FPCO finds to have a practice of consistently

k

ThelermrediscIosuresimIymeanslhalanagencyorinslilulionlhalreceivedrecordsfroman

education agency has disclosed that information or related education record information to a third party.

RediscIosuresgeneraIIyaresecondaryreorlsIinkedloindividuaIsludenlseducalionrecordslhallhe

receiving party provides to another institution or to the public.

l

Generally, education agencies have greater leeway in disclosing directory information among students

in the education setting (i.e. class lists). To protect sensitive privacy information, the USDOE clarified the

ban on SSN disclosures without prior student consent. Along these lines, the USDOE permitted the use

of student ID numbers in directory information disclosures. The USDOE clarified, however, that

educalionagenciesmuslencrylsludenlIDssuchlhallhirdarliesdonolhavelheabiIilyloIinklheID

loasludenlseducalionrecords

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 17 -

violating disclosure rules.

91

Prior to such an extreme consequence, an FPCO finding of fault

necessilales an educalion agencies deveIomenl of a voIunlary comIiance consenl

agreement.

92

The USDOE will not immediately withhold funding until the FPCO finds that the

agency under consent agreement fails to meet the voluntary rehabilitation conditions.

No Child Left Behind

FERPA functions as the most germane privacy protection tool for student education

records, but the more recent congressional passage of the NCLB

93

often enters into

consideration in efforts to build robust student-level databases. The law created a means for

slalesloreceivefederaIfundingforeducalionlocrealemainlainandsubmilsecified

categories of anonymous data to the U.S. Department ofIducalion

94

However, the law itself

does not set forth specific criteria or policies by which states should abide in their processing or

collecting such data.

95

Rather, NCLB only specifically prohibits states from creating a

nalionvidedalabaseofersonaIIyidenlifiabIeinformalion

96

and sets forth specific student-

level data sharing provisions for states seeking additional funding for migratory students.

97

NCLB has effectively pushed states towards collecting greater amounts of information

about sludenlsbullheslalulesiII-defined procedures for protecting data do not offer much

guidance in database development.

98

Thus, creating a robust student-level data warehouse at

lheslaleorIocaIIeveIshouIdconcenlralemoredireclIyonmeelingIIRIAs regulations, as

FERPA sets the predominant standard for student record protection.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996

WhiIe IIRIA resenls lhe mosl obvious reguIalory roleclions for sludenls rivacy

rights, many education agencies reference the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability

Act of 1996

99

HIIAAasarivacy law that may affect development of a federally compliant

dalavarehouseGeneraIIyHIIAAcoversroleclion ofindividuaIseIeclronicheaIlhrecords

for the purposes of creating a more efficient national health care system. HIPAA provides

similar data usage standards for health care institutions as FERPA does for education agencies.

The HIPAA Privacy Rule, though, focuses on electronic data exchange of health records

belveencoveredenlilieslhalengageincoveredlransaclions

100

A covered entity includes

health plans, health care clearinghouses, and health care providers that transmit health

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 18 -

information in electronic form in connection with covered transactions.

101

Covered

transactions are routine course of business electronic data exchanges between health care

providers and health plan administrators.

102

There are almost no occasions when a K-12 education agency would qualify as a covered

entity under HIPAA. HIPAA does not consider schools as covered entities, even if schools

maintain student health records electronically (i.e. immunization records).

103

Additionally,

HIPAA regulations include an express exception that defers to FERPA in cases where

educalionaI agencies mainlain or slore sludenls heaIlh records lhal lradilionaIIy vouId come

under HIPAA Privacy Rule protections.

104,105

InfaclHIIAAsdeferenceloIIRIAs|urisdiclion

in medically-related education records extends so far as to apply FERPA regulations to health

care providers that service juveniles in school settings, so long as those providers are operating

vilhinlheeducalionagencysscoeofconlroI

106

MaryIand educalion officiaIs reference lo lhe HIIAA Irivacy RuIe in dala varehouse

development discussions demonstrates the type of confusion that may have led to Maryland

and aIlimore Cilys inlegraled dala varehousing inaclion During an interview with MSDE

Deputy Superintendent Leslie Wilson, the high-ranking state education official referenced the

HIPAA compliance burdens as justifying MSDIs inaction in integrating lhe Slales sludenl-

level longitudinal databases across agencies.

107

Similarly, public health officials who may be

familiar with HIPAA regulations, yet unversed in FERPA protocols, may allow regulatory

misperceptions to persuade them into operating within public silos.

A 2008 DQC report (Smith, S., 2008) illustrates the legal misperception phenomenon that

hampers inter-agency collaboration. The reorl suggesls lhal IIRIAs exlensive education

record coverage often discourages non-education agencies from entering into agreements with

IocaIschooIdislriclsAvoidanceofIIRIAsregulations thus causes non-education agencies to

view FERPA as merely an education-based regulation too complicated to navigate. Further,

legal misperceptions may cause default reactions where agencies, including education

agencieserronlhesideofrestricting access to education records, even in cases in which child

welfare or other social service agencies are entitled to access [records] under and authorized

disclosure under the law.

108

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 19 -

By examining each of the most pertinent federal laws in the context of agency

integration, a well-designed robust data warehouse with clear operational protocols and data

disclosure systems should operate with few legal roadblocks so long as FERPA serves as the

overarching legal guidepost.

(2) Maryland State Laws

WhiIe foIIoving IIRIA rovides for a dala varehouses broad comIiance vilh

sludenlsfederaIrivacyroleclionsMaryIandandaIlimoreCilyofficiaIsaIsomuslconcern

themselves with state and local guidelines related to student data privacy.

MaryIandseducalionaIrecordsroleclionreguIalionsmirrorlhoseofIIRIAThrough

MaryIands adminislralive code

109

the Maryland State Board of Education incorporates

IIRIAs educalion record roleclions The adminislralive code aIso adols lhe Maryland

Student Records System Manual 2008 MDManuaIloreguIaleeducalionaIdalacoIIeclionand

management. The MD Manual expressly requires local education agencies to reference FERPA

to comply with student record confidentiality rules.

110

Creating a robust inter-agency data warehouse, though, would require state and local

officials to collect and link juvenile data that resides in non-educalionagenciesdalabasesThe

integrated data warehouse then would have to comply with state laws that govern disclosure of

non-education juvenile data. The chart available as Appendix II outlines the most pertinent and

relevant state laws that Maryland and Baltimore City policymakers would have to consider in

developing an integrated database.

As the appendix indicates, most agencies have specific statutory prohibitions on sharing

individualized information about children. Specifically, the Maryland Department of Juvenile

Services, the Department of Social Services, the Department of Public Safety, and the Maryland

Courts must comply with expressed laws related to juvenile data maintenance. While this

could pose a barrier for a wholesale release of information, agencies are permitted to enter into

agency-to-agency data-sharing agreements for the purposes of serving children many do so

already with the City Schools in an informal fashion, such as through the FARMS certification

process.

111,112

Thus, to comply with Maryland privacy law protections, Maryland state and City

Schools officials must either follow one of two paths: (1) enter into individualized sharing

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 20 -

agreements with each public agency, or (2) support state legislation that would eliminate

barriers to data-sharing at the state and local levels for data warehouse development purposes.

(B) Political Considerations

TheeffecliveuseofdalaisnolanevconcelloMaryIandoraIlimoreCilyTheslales

currenl governorGovMarlinOMaIIeygainednalionaInolorielyasMayorofaIlimoreCily

for his implementation of the CitiStat program in 2001.

113

The concepts behind CitiStat (now

implemented on the state level through StateStat) strongly correlate with the effective usage of a

robust student-level longitudinal data warehouse to improve student outcomes. CitiStat relied

on the foundational theory of action that by collecting comprehensive data about public

dearlmenlsroduclivilyofficiaIscouIdanaIyzeandacluondalalrendslomakeinformed

decisions.

114

A successful inter-agency student-level data warehouse would operate under the

same premise, focusing efficiency measures on leachers and rograms vaIue-added effect on

student achievement.

With a sympathetic Maryland governor in office and an education reform atmosphere

tied to the use of student data, creating a robust, integrated educational data warehouse in

Maryland could appear as an easily obtainable goal. When dealing with juvenile data,

however, clear political paths to database development may quickly become impasses.

MaryIands slricl slale Iavs againsl |uveniIe dala-sharing suggest that public agencies

maintenance, usage, and disclosure of juvenile data likely could face harsh political opposition.

While all potential opponents likely would not become clear until educational data

warehousing were already underway, two groups likely would stand at the forefront of the

causeloIimilcerlainaseclsofdalavarehousedeveIomenllheMaryIandsleachersunions

andrivacyadvocacygroussuchaslheAmericanCiviILiberliesUnionofMaryIandACLU-

MD

Teachers Unions

On the national scene many leachers unions have baIked al Secrelary of USDOI

DuncansreformrioriliesSecificaIIyleachersunionshaveinsisledlhal if data warehousing

has the capacity to link student-level growth data to teacher evaluation and performance, such

linking may undermine successful long-term education reform. Politico recently reported on

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 21 -

the gulf growing between Secretary Duncan and national teacher union leaders over USDOE

efforls lo exand slales sludenl dalabase infraslruclures

115

Randi Weingarten, national

IresidenloflheAmericanIederalionofTeachersAITcommenledDalaisimorlanl

bul if il ends u |usl becoming measuremenl lhals nol ubIic educalion The Politico

report also pointed to the National Educators Associations NIA letter in opposition to

proposed requirements of the Race to the Top grant competition: [Priorities encouraging

student-level database development are] ignoring slales righls lo enacl lheir ovn Iavs and

conslilulions

In Maryland, the national perspective influences local politics. Superintendent Leslie

WiIson suggesled lhal leacher unions oIilicaI infIuence in lhe MaryIand slale IegisIalure

potentially played a past roIe in MSDI officiaIs unviIIingness lo ush for a statewide data

warehouse that could link teacher performance to student outcomes.

116

Teacher union

opponents generally view student growth measurement as an inaccurate measure of teacher

effectiveness. Further, these organizations argue that comprehensive student databases could

misalign district priorities for reform and reduce creativity in classrooms in Maryland.

117

Another anecdotal example of potential Maryland teacher union opposition occurred

during the 2009 General Assembly session. State House Delegate Anne Kaiser introduced

legislation on behalf of MSDE that would enable the State to create teacher identification

numbers for inclusion in the student-level longitudinal data warehouse. Although H.B. 587

passed, teacher union negotiations with MSDI rior lo lhe biIIs inlroduclion Ied lo slalulory

language that prevented local agencies from tying student performance through the teacher

identification number to teacher evaluations.

118

Recent education coverage of the collective bargaining negotiations in New Haven, CT,

lhough suggesls lhal lhe aIlimore Teachers Union TU an AIT affiIiale may be more

willing to support a considered data warehousing effort if education officials include union

input early in the decision-making process. The local New Haven AFT-affiliated teachers union

and the New Haven Public Schools came to agreement on progressive contract terms that

included expanded use of data; teacher performance pay based on student achievement growth;

greater emphasis on testing; and school-based operational freedom.

119

Union support largely

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 22 -

slemmed from lhe schooI dislricls viIIingness lo eslabIishcoIIaboralive vorkgrous belveen

union reresenlalives and dislricl adminislralors lo decide on lhe conlracls crilicaI

implementation details.

120

By investing the union at the front-end of policy development, New

Haven teachers and administrators may have presented an ideal framework for Maryland and

aIlimoreCilysdalavarehouseadvocalesshouIdadvocates soon seek to improve the City and

Staleseducaliondalainfraslruclure

Privacy Advocacy Groups

Privacy watch groups likely would raise sound and reasoned concern over some aspects

of robust inter-agency data warehouse development. Collecting and centralizing juvenile data

from agencies across the public spectrum could place a wealth of information at the hands of

government officials. Further, through illegal or negligent actions, an insecure database could

expose sensitive information about students to non-government or ill-intentioned entities.

While the ACLU-MD has praised Baltimore City efforts to address root causes of at-risk City

SchooIssludenlshabiluaIlruancyissuesanddisciIinaryvioIalionssuorlfordalaanaIysis

likely would only go so far should the data warehouse fail to include proper safeguards.

Take, for example, media coverage in Anne Arudel County, Maryland, where police and

school officials are entering the data integration discussion on the basis of identifying gang

activity.

121

Governmenl officiaIs collection of juvenile data allows for immense reporting

capabilities. But, advocacy groups may suggest that positive intentions in data warehouse

creation could result in harmful outcomes, such as socioeconomic-based law enforcement

largelinginMaryIandsubIic schools.

122

Similarly, the ACLU-MD could point to the July 2008 Baltimore Sun series that exposed a

Maryland State Police undercover investigation of peace activists and anti-death penalty

groups.

123

In the State Police spying controversy, misinterpretation of available data about

Maryland peace advocacy groups led to a highly secretive and intrusive covert police operation.

Thus, whenever government officials have access to sensitive personal information, groups

such as ACLU-MD may have good reason for advocating against a robust student-level

database if proper protections are not in place.

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 23 -

MaryIand rivacy and sludenls righls advocacy grous are slrongIy avare of and

acliveaboulubIicagenciesefforlslosharedala

124

Groups such as Legal Aid and ACLU-MD

often track FERPA compliance vigilantly, and these groups regularly communicate with state

and local education officials to ensure data protection.

125

Evidence of this active oversight is

evident in communications from ACLU-MDseducalionseciaIisl

It would be important [for ACLU-MD] to consult with privacy technology

officers who can provide the detailed planning assistance based on the

technology the school is going to use and the goals of the programthe issues

arise because of poor implementation of principles as much as with not thinking

through the broad policy itself.

126

During a phone interview, Cindy Boersma, ACLU-MDsLegisIaliveDireclordiscussed

severaIolherolenliaIrisksindalavarehousedeveIomenlandnoledlhallheACLUs

national office has taken interest in state and local efforts to build such databases.

127

Some of these foreseeable threats include: (1) the potential consequences of centralizing

information in one place so as to localize all sensitive information for interested parties;

(2) the effect data warehousing has on degrading the nolionofconsenlinanindividuaIs

release of personal data; (3) the difficulty around minimization only collecting necessary

data when more data may be available; (4) avoiding technology creep collecting data

from various sources unnecessarily because the technology allows officials to do so; (5)

data-sharing creep the difficulty in preventing release of information to other public

agencies once another agency has already collected the information; (6) data accuracy

and data-purging insufficiencies; (7) problems in disclosures that fail to de-identify

individuaIs eilher acliveIy or assiveIy and minimizing agency officiaIs access lo

data when roles of authority are unclear.

128

Successfully navigating MaryIandadvocacygrousdisagreemenlslhoughisossibIe

In 2006, the Maryland General Assembly overrode then-Governor IhrIichs velo of H

ChiIdren Records Access by lhe aIlimore Cily HeaIlh Dearlmenl

129

HB 900 revised

nearIy every seclion of MaryIands slalulory code relating to the privacy of juvenile records,

other than those records maintained by the public schools. Specifically, the bill permitted the

BCHD lo access an exlensive range of slale agencies personal data tied to at-risk juveniles.

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 24 -

Access lhe |uveniIe dala hinged on CHDs efforls lo develop programs to reduce youth

violence in Baltimore. Through H s assage lhe BCHD gained regulated access to

protected juvenile data at unprecedented levels.

130

Thus, developing innovative and

progressive ways to integrate juvenile data is not unprecedented, and crafting state legislation

to initiatives aimed at helping at-risk youth may be successful.

Ultimately, overcoming data warehouse opposition will come through education

officiaIs inlenlionaI allemls lo bring slakehoIders logelher as earIy as ossibIe in lhe

development and planning stages of the warehousing process. By including potential

adversaries at the front-end of development, Maryland and Baltimore City officials may be able

lo creale a more effeclive syslem lhal baIances aII arlies inleresls Iurlhermore dala

varehouse advocales musl manage aII arlies execlalions aIong lhe vay of deveIomenl

These advocates must continually return to basic principles and motivations behind the data

warehousing effort to ensure that the final infrastructure achieves educational goals while

avoiding unnecessary data collection and disclosure.

131

IV. Recommendations & Conclusions

Maryland and Baltimore Citys insufficienl dala infraslruclures hamer Cily SchooIs

sludenls by reducing educalors abiIilies lo largel inlervenlions roacliveIy and lo aIIocale

resources efficiently. Unavailable robust student data reports also may deny the City Schools

the ability to link teacher performance to student growth, and may contribute to a prevalence of

unquaIified or unfil leachers in lhe Cilys cIassrooms The currenl almoshere of educalion

reform and federal funding under USDOE Secretary Duncan, however, sets the stage for

MaryIandandaIlimoreCilysoorlunilylobridgelhedalabasega

To take advantage of the distinctive chance at acquiring unprecedented federal

education dollars, Maryland and Baltimore City policymakers must consider important legal,

political, and policy implications. These spheres of influence will govern whether successful

data infrastructure revitalization will be possible.

To frame the discussion, policymakers must recognize that robust student-level data

systems necessitate government collection of massive amounts of potentially sensitive and

personal information about students. City and State policymakers, therefore, must navigate

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 25 -

oonenlsconcernsaslheyreIalelofederaIandslaleIavsgoverningsludenlsrivacyrighls

Second, accessing and utilizing student data has the potential to raise serious concerns amongst

someofMaryIandsslrongesloIilicaIadvocacygrousMaryIandandaIlimoreCilyofficiaIs

therefore, must maneuver delicately through hesitations derived from potential political and

budgetary landmines.

m

The following summary recommendations attempt to provide a

generalized guide for lheCilyandSlalesdata warehouse proponents to move forward:

RccnmmcndatinnFncusnnBa!timnrcCitysDataWarchnuscDevelopment. Rather

than immediately looking towards creating a statewide data warehouse, Baltimore City officials

should use the current RFP data management system process to integrate data from non-

education public agencies working with juveniles. Ultimately, MSDE officials do not need the

more sensitive information about students to comply with most reporting tasks. Officials

working at the local level are most able to affect student achievement, and data warehousing at

the local level should be the focus point for integrated data-sharing efforts.

132

Recommendation 2: Convene a Stakeholder Workgroup of State and Local Officials

and Advocacy Groups. The Baltimore City Council or the Maryland General Assembly should

pass legislation to provide the opportunily for MaryIands educalion oIicymakers

stakeholders to convene for the purposes of discussing juvenile data integration amongst the

Slalesagencies The workgroup should consist of representatives from MSDE, the City Schools

(and additional school dislriclsasnecessaryDSSD}SDLLRDHRleachersunionsrivacy

advocacy groups, technology specialists, state and local politicians, parent associations, and

representatives from the legal community. With this initial gathering, the workgroup should

determine all other potential stakeholders that may have an interest in the data warehouse

development to ensure broad front-end investment. Secondary invitations should follow the

gathering of the most obvious constituents. Ultimately, the workgroup would be charged with

m

Given this aersuroselhefollowing section focuses heavily on legal and policy issues. Full

consideration of technological integration issues related to a student database will be critical for

MaryIandandCilySchooIsoIicymakerslosuccessfuIIydeveIoarobuslIongiludinaIdata warehouse.

However, the paper recognizes that further, specialized studies will be necessary to fully encompass all

factors that may influence effective database programming.

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 26 -

determining the tiered need for improving data infrastructures based on the priorities outlined

by the DQC.

Recommendation 3: Provide the Workgroup with Specific Expected Outcomes.

Relevant legislation should charge the workgroup with making recommendations about the

following areas of inter-agency, data-sharing decision points. (a) Prioritized outcomes that the

successful City or State robust longitudinal databases would offer to facilitate backward

planning of the development process; (b) design plans for operational structures; (c) an

oeralionaIIanlhalcIarifiesagenciesroIesinanefforlloabidebyIIRIAandslalerivacy

law provisions; (d) a series of plans that address issues of initial and continual training on the

collection, storage, and use of juvenile data; (e) a list of agencies or groups that would

contribute data and information to the warehouse; (f) a list of agencies and organizations that

would have an interest in obtaining reports or raw data from the robust student-level data

system; (g) data protection and encryption plans that would become standardized across

participating agencies; and (h) a tiered, estimated cost-out of initial development plans for

recommended work moving forward.

n,133

Recommendation 4: Develop Standardized Inter-Agency Data-Sharing

Confidentiality Agreements. Presuming the workgroup ultimately advocates a need to

imrove MaryIands educalionaI andinler-agency data infrastructures, the workgroup should

outline and sponsor enabling data-sharing legislation at the state level and/or develop

slandardized Memorandums of Underslanding MOU. These agreements must permit

broader juvenile data-sharing while maintaining privacy protections at all levels and within all

participating agencies. Given the strict privacy laws in Maryland around juvenile data, the

workgroup should look towards the efforts of the BCHD to determine if such an expansive

data-sharing legislative effort would be feasible. Additionally, the workgroup should look

towards other state or local data-sharing agencies outside of Maryland, and specialized think

n

A critical component of creating a robust data system is establishing buy-in from needed

agenciesandcoIIaboralivearlnersThereviIIoflenbeanissueaslovhichagencyovnslhe

data or is responsible for reporting out data for necessary reports.

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 27 -

tanks that may be able to offer best-practice agreements or statutory language that effectively

facilitates data integration.

134

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 28 -

- APPENDICES -

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 29 -

Appendix I: FERPA Detailed Overview Table by Disclosure Examples

Type of

Information

Release

Type of

Disclosure

Explanation Authority

Relevance to State/Local Data

Warehousing

LEA release of

aggregated,

unidentified

student data to

third party or

public

Not a

Disclosure

Although the data includes information

about students, and likely aggregates

individuaIsludenlseducalionrecords

no disclosure occurs because third

parties are unable to link data to

individual students.

34 C.F.R.

99.3 (2009)

Unidentified data reports about

schools and school districts are

permissible.

135

This allowable

action permits states to publish

yearly report cards about student

performance, and may allow

dynamic databases to produce

more comprehensive aggregated

reports.

LEA release of

education

records to

teacher or school

officials within

local district

Lawful

Disclosure

Local districts may freely share

sludenlseducalionrecordsloofficiaIs

within the same district, so long as

sharingoccursforIegilimale

educalionaIinleresls

20 U.S.C.

1232g(b)(1)

(A)

20 U.S.C.

6311(b)(3)(C)

(xii)

Under FERPA, locally maintained

data systems are less subject to

violations. Thus, creating a local

dalavarehouseIimilsadislricls

liability exposure.

LEA release of

education

records to state

agency for

evaluation or

audit of local

programs, or for

accountability

purposes

Lawful

Disclosure

FERPA expressly permits disclosure of

LIAseducalionrecordsloslale

education agencies for evaluative

purposes. However, the state agency

may not redisclose the personally

identifiable education records, and

must destroy the records after

evaluation is complete.

20 U.S.C.

1232g(b)(1)

(C), (b)(3),

(b)(5) (West

2009)

FERPA recognizes the

organizational relationships

between state and local education

agencies. As new FERPA

regulations indicate, such data-

sharing is expected and advised.

136

LEA release of

sludenls

assessment,

enrollment, and

graduation data

for purposes of

NCLB

Lawful

Disclosure

NCLB requires local districts to provide

individual student data for

accountability purposes. While states

and federal agencies must protect this

personally identifiable data about

students, the disclosure is lawful.

No Child Left

Behind Act of

2001, 20

U.S.C. 6311

(b)(3)(B)

Greater amounts of federal

funding for local education

agencies increases the likelihood

that federal offices will hold local

school districts accountable for

reform efforts. Statewide, or

robust local data warehouses,

provide such an infrastructure for

federal reporting.

LEA release of

individual

sludenls

education

records to a

contractor that

maintains a

database on an

LIAsbehaIf

Lawful

Disclosure

FERPA recognizes the resource and

technological restraints that many LEAs

face. Thus, the law permits districts to

contract out database services when the

terms of the data-sharing are expressly

outlined. The LEA or state agency must

havedireclconlroIoverlheconlraclors

operations. Contractors must exercise

the same heightened security around

sludenlseducation records as the

disclosing LEA would have.

34 C.F.R.

99.31(a)(1)(i)

(B) (West

2009)

34 C.F.R.

99.33(a) (West

2009)

34 C.F.R.

99.35 (West

IIRIAsudaledreguIalions

clarified this type of disclosure

between public agencies and

contractors. The clearer language

likely permits a third party

contractor the ability to maintain

andoeraleaLIAsdala

warehouse, so long as the LEA

clearly defines the scope of the

sharing agreements.

IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES IN BALTIMORE CITY WITH INTEGRATED DATA SYSTEMS

2010

- 30 -

Type of

Information

Release

Type of

Disclosure

Explanation Authority

Relevance to State/Local Data

Warehousing

Contractors also may not use the data

for purposes other than those outlined

in initial disclosure agreement.

Importantly, disclosing education

agenciesareIiabIeforanyconlraclors

FERPA violation.

2009)

LEA release of

education

records to

police, parents,

or other parties

to prevent

generalized

threat to

students

Unlawful

Disclosure

LEAs may only release education

records to such parties for health and

safety reasons when the data release is

necessaryloroleclagainsla

significant and articulable threat to

heaIlhorsafelyofanolhersludenl

137

or another party. USDOE violation

investigators will review a data release

under these conditions by a totality of

the circumstances standard.

34 C.F.R.

99.36(a) (West

2009)

While a robust longitudinal

student database may maintain

inter-agency juvenile data, release

of this data is impermissible unless

a clear emergency exists.

LEA or state

release of

education

records for

purpose of a

longitudinal

data system

Lawful

Disclosure

2008 revised FERPA regulations

expressly permit release of education

records for maintenance within a

statewide data system.

34 C.F.R.

99.35(b) (West

2009)

With this recent revision, the

USDOE expressed a clear

commitment to providing

incentives for states to expand

educational databases.

138

Third party

breaches LEAs

records to obtain

education

records

Likely

Unlawful

Disclosure

The revised FERPA guidelines set

standards that education agencies must

factor when establishing technological

safeguarding protocols. If an education

agencydoesnolmeelIIRIAs

encryption guidelines, the agency may

be liable for an unlawful disclosure.

34 C.F.R.

99.62, .64, .65,

.66 (West

2009)

In establishing a robust student

data warehouse, state or local

officials must exercise great care in

establishing technological

infrastructures.

LEA release to

non-public or

research

agencies that

conduct

educational

studies

Likely

Lawful

Disclosure

2008 revised FERPA guidelines

included language within the

regulation to clarify the role that

outside parties may play in obtaining

education records for research

purposes. The regulations highlight the

need to de-identify information prior to

release, and provide methods for

permissible de-identification (i.e.

stripping potentially identifiable

information about a student from

linked educational statistics). The

revised regulations also provide factors

that LEAs or state education agencies

should consider in determining what

education record data to provide, and

in what means agencies should about

providing it.

139

34 C.F.R.

99.31(a)(6)

(West 2009)

With the creation of a robust

educational data warehouse, a

local or state agency likely will

find researchers who desire access