Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Cap STR Ukrein

Cap STR Ukrein

Cargado por

yr_pathak9790Descripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Cap STR Ukrein

Cap STR Ukrein

Cargado por

yr_pathak9790Copyright:

Formatos disponibles

DL1LRMINAN1S Ol CAPI1AL

S1RUC1URL Ol UKRAINIAN

CORPORA1IONS

by

Oleh Myroshnichenko

A thesis submitted in partial ulilment o

the requirements or the degree o

Master o Arts in Lconomics

National Uniersity Kyi-Mohyla Academy`

Lconomics Lducation and Research Consortium

Master`s Program in Lconomics

2004

Approed by ___________________________________________________

Ms.Sitlana Budagoska ,lead o the State Lxamination Committee,

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Program Authorized

to Oer Degree Master`s Program in Lconomics,

NaUKMA

Date _________________________________________________________

National Uniersity Kyi-Mohyla Academy`

Abstract

Determinants of Capital Structure of Ukrainian

Corporations

by Oleh Myroshnichenko

lead o the State Lxamination Committee: Ms.Sitlana Budagoska,

Lconomist, \orld Bank o Ukraine

1he research aims at determining the key actors o Ukrainian

corporations` capital structure building as well as testing o classic

capital structure theories. 1esting has shown that short- and long-

term inancing decisions hae dierent determining actors.

Speciically, proitability and tangibility ratios are negatiely

correlated with raction o external inancing in short run. On the

other hand, long-term leerage is a positie unction o

corporation`s size. Short run inancing horizon is dominated by

pecking order theory, in which cash lows and depreciation are a

major source o inancing. Long run inancing exhibits tendency to

trade-o theory, in which corporations are trying to maintain target

leerage ratio.

1ABLL Ol CON1LN1S

1. Introduction .....................................................................................................................1

2. Literature Reiew.............................................................................................................5

2.1 Caitat trvctvre 1beorie. ..........................................................................................5

2.2 Covarivg tbe 1ro 1beorie. ................................................................................... 12

2. Cta..ificatiov of covovetric Moaet. |.ea iv Caitat trvctvre vre.tigatiov. ........ 14

3. 1rends in Corporation`s Inestment linancing in Ukraine ................................. 19

4. Methodology ................................................................................................................. 22

1.1 Moaet. ava 1ariabte. |.ea iv tbe Cvrrevt tva, ................................................... 22

1.2 1ariabte.................................................................................................................. 23

1.2.1 ererage Mea.vre................................................................................................. 23

1.2.2 tavator, 1ariabte. ........................................................................................ 24

5. Dataset Description ..................................................................................................... 29

6. Results and their interpretation.................................................................................. 35

.1 ctvaea regre..or. .................................................................................................. 35

.2 Cov.i.tevc, cbec/..................................................................................................... 36

. ecificatiov of regre..iov.......................................................................................... 36

.1 bortterv tererage regre..iov. .................................................................................. 3

.: ovgterv tererage regre..iov.................................................................................... 40

Conclusions........................................................................................................................ 43

Bibliography....................................................................................................................... 45

Appendices......................................................................................................................... 50

ii

LIS1 Ol lIGURLS

^vvber Page

Iigures

igvre 1. vcove catcvtatiov for firv. ritb tro etreve caitat .trvctvre atterv.

igvre 2. tatic traaeoff tbeor, of caitat .trvctvre

igvre . De.critire .tati.tic. of .avte rariabte. iv ivav.tr, fraveror/ ;.etectea ivav.trie.) 0

igvre 1. Rav/ivg of regiov. b, tererage ratve 2

igvre :. Rav/ivg of ;.etectea) ivav.trie. b, tererage ratve

igvre . 1 tererage regre..iov.

igvre . 1 tererage regre..iov. 10

Appendices

.evai 1. 1otat Debt Ratio for .etectea covvtrie.

.evai 2. Regi.terea bare ..ve.: Cvvvtatire 1otvve

.evai . bare i..ve. b, var/et articiavt., bv |.

iii

ACKNO\LLDGMLN1S

I want to express my deep gratitude to all people who adised me in the process o

writing this research. 1hey are my thesis adisor Daid Brown rom leriot-\att

Uniersity, who proided many comments and insightul ideas, as well as Julian

lennema. 1his research would not be possible without actie support o proessor

1om Coupe rom Kyi School o Lconomics in getting the necessary data. Daid

Bowe rom Uniersity o Manchester proided initial remarks or the research,

Volodimir Bilotkach rom Uniersity o Arizona made reiew o the thesis and came

up with useul comments, Valentin Zelenyuk being critical, motiated me to improe

structure o the paper, Viktor Radchenko, Uniersity o Minnesota graduate proided

aluable suggestions as to the real state o aairs in the ield o inestment inancing in

Ukraine. I also thank group mates in LLRC class 2004, which made useul remarks

during my presentations.

C b a t e r 1

Introduction

In making decisions on which sources to use or inestment inancing, corporate inanciers in

transition countries cannot boast haing a wide choice o inancing instruments. 1his list may

include bank loans, issues o shares, bonds and possibly ew other instruments. 1he decision on in

which degree one or another source o inancing should be used is oten reerred to as a classical

problem o cost o capital ,or weighted aerage cost o capital - \ACC, minimization.

Neertheless, \ACC cannot ully explain changes in capital structure. lor example, major

stakeholders may be interested in such inancing that preseres the existing ownership structure

,control motie,. 1his consideration is not accounted or in \ACC. Businesses in transition

countries may not een hae an alternatie to choose rom while seeking or inancing o their

actiity. 1he reason requently lies in a poorly deeloped inancial market and illiquid ,poorly

collaterized, assets possessed by the businesses.

1he recourse to dierent inancial deices is determined by particular economic, technical, and

institutional actors. lrom technical point o iew, a bank loan can be lexible enough in terms o

repayment conditions, but costly at the same time. Common shares or a public company allow

obtaining cheap capital but at the expense o erosion o control by current shareholders, and so on.

Company speciic actors, like size, reputation, growth potential, etc. are also to inluence capital

structure decisions. It can be concluded thereore that only a clear business strategy would help to

ealuate all pros and contras o a certain capital structure choice. 1he role o the researcher here is

to see how market agents with similar irm speciic characteristics architect their inancing mix.

2

\hile not a erdict, such an inestigation proides a decision maker with useul background on

which the decision is to be made.

In 1958 Modigliani and Miller published their amous 1he Cost o Capital, Corporation linance

and 1heory o Inestment`. In their article MM put orward the capital structure irreleance`

argument stating that in rictionless markets, with no taxes or transaction costs, capital structure is

irreleant - does not aect market alue o irm. Some academicians receied the work as being

controersial ,Rose, 1959, Durand, 1959,. 1he critics basically stated that in real world the main

assumptions neer hold true and hence capital structure irreleance` is nothing but a iction.

loweer, as brisk answers o the authors proed, they made it explicit that the underlying

assumptions are not likely to hold in real world situations. Moreoer, they stated that in a non-

perect` world there are actors inluencing capital structure decisions by irms and the paper itsel is

the beginning o the attack on the cost o capital concept and related problems`. It is that period

rom which the whole strand o literature on capital structure actors began to emerge.

1he empirical papers on the topic usually test or such company speciic actors as growth

opportunities, size, tax rate, proitability, and others when trying to explain the dynamics o capital

structure ,e.g. Banerjee et. at., 2000, Niorozhkin, 2000, Gaud et. at., 2003 to call just a ew authors,.

Another group o actors tested or are macroeconomic, like inlation, stock market alue,GDP,

real GDP growth rate ,Desai, 2003, Booth et. at., 2001,.

3

Capital structure determinants and dynamics were inestigated using dierent panel data

speciications in many economies ,see, or instance, Gaud et. at. ,2003,, Philippe et. at. ,2003,, and

others,. 1hese explorations as well as my paper enable to test or alidity o some o the theories o

capital structure. Current analysis ocuses speciically on testing the releance o agency cost,trade-

o ramework

1

and pecking order theory

2

. 1hese concepts will be detailed later in the paper. 1he

results obtained contribute to the resolution o theoretical disputes using a dataset o Ukrainian

joint-stock companies. Despite a big number o empirical studies, deoted to capital structure

choices in deeloped, deeloping and transition countries, Ukrainian companies` capital structure

has not been inestigated. lence, using the results o preious researches, the study allows to get a

close look at inancing patterns and determinants o Ukrainian businesses capital structures. 1his is

important in iew that Ukrainian corporations are trying to increase their competitieness both

domestically and internationally. Increasing competition ,particularly in ood processing, banking

serices, I1 sector, etc., orces Ukrainian businesses to compare the key characteristics o their rials

with those o their own, with capital architecture being one o such characteristics. 1hus, using

regression coeicients obtained, it is possible to calculate the expected leerage alue or a typical

company on particular market.

1he rest o the paper proceeds as ollows: part 2 elaborates on capital structure theories, classiies

basic methodological approaches used in preious research, and gies some empirical eidence

concerning the main indings in the capital structure researches, part 3 describes recent trends o

1

It is also called target debt leel model`. 1his theory originates rom Miller ,19,

2

Myers and Majlu ,1984,

4

inestment inancing by irms in Ukraine, part 4 presents the methodology or current study

including ariables and econometric speciications used, part 5 characterizes dataset used or testing

and estimation. 6

th

part discusses the results obtained and is ollowed by the main conclusions o the

paper.

5

C b a t e r 2

Literature Review

2.1 Caitat trvctvre 1beorie.

Perhaps, o the most comprehensie reiews on capital structure theories is that composed by

larris and Rai ,1991,. \e can broadly distinguish between tax- and non-tax drien capital

structure theories. lR concentrate on the latter. Not going deeply in details concerning all models

analyzed in the work, it is suicient to outline a general classiication used by the authors. lR

distinguish the ollowing classes o capital structure models:

Models based on agency costs,

Models using asymmetric inormation ,essentially pecking order theory ramework,,

Interactions o capital structure with behaior in the product or input market or with

characteristics o products or inputs,

Models based on corporate control considerations.

1he most popular o the tax-drien capital structure theories is a trade-o supposition, which is to

be elaborated on below.

In corporate inance courses trade-o and pecking order theories are studied most widely. 1he

reason seems to be in their high intuitie appeal and prolieration.

2.J.J 1rade-off 1heory

1here are two types o the trade-o theory: static and dynamic.

6

Static trade-o theory assumes ixed external enironment. lere we iew a irm`s optimal debt ratio

on the grounds o a trade-o between the costs and beneits o borrowing while holding the irm`s

assets and inestment plans constant. In this case the irm is balancing the beneit o debt induced

tax shield ,due to deductibility o interest payments or taxation purposes, against the costs o

inancial distress, which basically reers to a risk on non-payment. 1he irm is supposed to change

equity or debt or debt or equity until the alue o the irm is maximized. 1his is the gist o the

trade-o.

Dynamic trade-o ramework allows or ariability in outside actors, like product demand, actors

prices, etc. Changes in external and internal enironment o the irm necessitate changes in optimal

debt ratio. lere adjustment costs come to the ore. In the absence o the adjustment costs the irm

is able to immediately ine-tune its debt size to the market conditions. Adjustment costs stipulate

lags in coming to optimal debt ratio

3

. One o the examples o such costs is the commission charged

by the underwriter o stocks and bonds. lurthermore, the irm compares the beneits o the optimal

debt ratio with the costs o adjusting to it. Debt ratio changes only when potential beneits o haing

optimal debt outweigh adjustment costs o moing to it. Accounting or adjustment costs helps in

explaining the act that many irms may stray rom optimal debt ratios or long periods o time. As

Myers ,1984, notices in his 1he Capital Structure Puzzle`: testing inancing pattern using cross-

section methodology should point out the reason or dierences in debt ratios: whether the irms

hae dierent target debt ratios or their debts dierge rom the optimum`. Moreoer, the higher the

3

Debt ratio can be deined in dierent ways, which is not essential in the gien context

adjustment costs are, the more important they become, crowding out in a way possibilities or

adjustment.

Oerall, trade-o theory utters that an increase in the irm`s leerage increases its market alue due

to debt induced tax shield eect. Let us briely describe the eect o debt-induced tax shield.

\e consider two hypothetical cases o income calculation or irms A and B. A and B are

completely identical irms with the only dierence that A is inanced ully with debt and B is entirely

equity-inanced. Current corporate income tax is 30. Both companies hae just obtained reenue

o >100. A pays 5 o interest to its bondholders whereas B pays 5 o its reenue to the

shareholders. Interest payment or A is tax deductible. Assume that production expenses are 50 o

total reenues. 1he table below presents income calculation procedure.

igvre 1. Income calculation or irms with two extreme capital structure patterns

Company A B

100

debt

100

equity

Initial revenue >100 >100

Production expenses >50 >50

Payment to bondholders >5 -

Pre tax earnings >45 >50

1ax payment ~>450.3 ~>500.3

After tax earnings >31.5 >35

Dividends - >5

Residual earnings >31.5 >30

8

As can be seen, A earns more. lence, haing identical technologies and all other parameters but

capital structures, debt-inanced corporation gets higher ree cash lows due to tax deductibility o

interest payments. As a result, discounted alue o cash low streams rom A exceeds that o B.

1hereore market alue o irm A exceeds B. 1his eect can be explained in detail as ollows.

Suppose we are to obtain unds at the expense o equity capital. 1hen the amount o diidends,

which we want to be equal to the amount o the interest paid, will be taxed beore payment. In case

o bonds, we can repay the same quantity o cash spending smaller amount o money due to debt

induced tax shield. lence, in our case the dierence is: payment to capital owners multiplied by

income tax rate: >50.3~1.5. 1his is exactly the debt induced tax shield adantage we hae obtained

aboe. Still, this is not the end o the story. In the real world, irms` capital structure is a mix o both

debt and equity. lence, depending upon the share o debt s. share o equity, the example aboe

will bring dierent residual earnings ranging rom >30 to >31.5. Moreoer, the costs o inancial

distress or a irm increase along with the share o debt in the capital structure. In other words, the

more debt the irm has accumulated the more likely that it will hae diiculties repaying it or will

een deault on its debt. lence, these costs, which eectiely represent a non-payment risk, will

tend to decrease irm`s alue. linally we see two eects: debt induced tax shield eect and cost o

inancial distress, working in opposite directions. 1hat is while the ormer increases market alue o

the irm and the latter decreases it. It is this trade o which seres as a major concern or many

irms in making decisions on how much debt to take on. 1his idea or a static trade o case is

depicted on ligure 1 below. 1he horizontal axis denotes a major debt ratio, which is a ratio o total

debt to total assets, the ertical axis indicates market alue o the irm. 1he horizontal line, which is

parallel to the Debt,Assets axis and lies aboe it, denotes the alue o the irm without any debt.

9

1he upsloping straight line relects an increment in market alue o the irm due to debt induced tax

shield eect. 1he Actual market alue o the irm` line results rom subtraction o deault risk costs

rom riskless debt` upsloping straight line. It is the highest point on Actual market alue o the

irm` line that shows the existence o a point o maximum irm`s alue. Calculation o Debt,Assets

ratio corresponding to this point is the main ocus in the application o static trade-o ramework.

igvre 2. Static trade-o theory o capital structure ,Ross et. at., 2000,

2.J.2 Pecking Order 1heory

Suppose a irm has proitable inestment opportunities. In order to realize these opportunities it

needs unds. 1he irm can obtain the necessary unds in dierent ways. One o them is to use

Cost o inancial

distress

lirm`s alue in the

absence o non-

payment risk

Debt,Assets

Ratio

Market

Value

o the

lirm

Increment in

irm`s alue due

to debt induced

tax shield

Market alue

o the irm

with no-debt

Actual market alue o

the irm

Optimal debt

point

10

inancial instruments aailable on the market. 1he irm may try to issue new stock at a air alue.

1he air alue here corresponds to the expected alue o company`s stock ater successul

completion o the inestment project. Unortunately here is a problem stemming rom inormation

asymmetry. It is insiders in irst place who can ealuate the true earnings potential o the project.

Inormation asymmetry quite oten makes inestors underestimate potential returns rom the

projects proposed. 1hereore, in order to make equity oering successul, it would hae to be

underpriced. In this case new inestors would buy stock at the price below its real alue. As a result

they eectiely obtain rights or uture earnings in the amount that exceeds their inestment. 1he

losers in this situation are incumbent shareholders. 1hey sacriice a raction o their stock alue in

aor o new equity buyers. 1his problem makes current shareholders unwilling to embark upon

issuing stock as a way o getting inance. \et inormation asymmetry problem can be aoided i the

irm inances the project using an instrument that aces less or no asymmetric inormation problem

and underaluation stemming rom it. lor instance, internal unds

4

and riskless debt cause no

underaluation. 1he reason is that the ormer belongs to the irm ,insiders, itsel, while the latter

promises a ixed rate o return regardless o the inestment project results. Consequently, the

corporation will preer these two or inancing purposes. Since there is no completely riskless debt

,at least in case o corporations,, bonds and loans do create some inormation asymmetry. Still this

asymmetry is signiicantly smaller than in the case o equity issue. Myers ,1984, reers to this

hierarchical sequence o preerences in inancing as pecking order` theory o inancing. In other

words, capital structure will be drien by irms` desire to inance new inestments irst internally,

then using low-risk debt, and inally with equity only as a last resort. In act it is not only inormation

4

primarily cash low, which is sum o depreciation and net income

11

asymmetry but also a corresponding risk that sets ground or the price o inancing. 1hough not

explicitly stated, pecking order theory incorporates the risk attributed to dierent inancial

instruments. 1his risk along with inormation asymmetry is relected in the price o unds obtained

rom dierent sources.

Below ollow some implications o the pecking order` theory o Myers:

,1, upon announcement o an equity issue, the market alue o the irm`s existing shares will

all - anticipation o alue takeoer by new shareholders,

,2, inancing using internal unds or riskless debt ,or a security which alue is independent o

the inormation asymmetry, will not coney inormation and will not result in any stock

price reaction,

,3, new projects will tend to be inanced mainly rom internal sources or the proceeds rom

low-risk debt issues,

,4, as Korajszyk et. at. ,1990, state, . the underinestment problem is least seere ater

inormation releases such as annual reports and earnings announcements`. It implies that

equity issues will tend to occur right ater these eents since inormation asymmetry at those

moments is least,

,5, the companies with smaller share o tangible assets tend to be more subject to inormation

asymmetries. It is because intangible assets are more diicult to price. 1hereore intangible

irms` will ace underinestment problem more oten. lence, ceteri. aribv., these irms will

tend to accumulate more debt oer time.

12

2.2 Covarivg tbe 1ro 1beorie.

\hat is the principal dierence between the two theories 1rade-o approach searches or an optimal

debt-equity ratio. Pecking order approach calls or maximum utilization o the cheapest instrument

aailable. In pecking order world` these cheap instruments are ,in order o preerence, internal unds,

debt and equity. 1he two theories approach capital structure question rom dierent points. 1rade-o

theory tries to maximize market alue o the company. Pecking order principle pursues minimization

o the cost o capital using the least asymmetric` unds. lere meant the sources o inancing, which

are obtained rom the most inormed or relatiely insured ,in case o bonds, parties. 1he natural

question arising here is whether the point o maximum market capitalization conerges with the point

o minimum costs o unds

Let us consider some hypothetical example. Suppose ABC company has inexhaustible inestment

opportunities in which it can earn the return high enough to coer inancing costs. 1he chie inancial

oicer ,ClO, o ABC aces strategic dilemma: which principle o inancing to choose 1he

alternaties, in our case, boils down to the two: trade-o or pecking order code.

1rade-off principle of financing. Let us assume the ClO chooses trade-o principle o inancing.

In this case s,he would always try to hae certain inancing structure in which the ratio o debt to

equity is kept constant to maximize market alue o the irm. \e shall emphasize that with expansion

o business, the proportion o external to internal unds is not supposed to change!

Pecking order principle of financing. Now the ClO chooses hierarchical sequence o inancing.

lere s,he would use unds in pecking order as has been described earlier. In this case, as company

uses up all internal unds ,which cost is about a risk-ree rate,, it switches to debt inancing and

13

corporation`s cost o capital increases. Later on at the point where debt inancing cost reach the cost

o equity inancing ,because at some point inancial distress costs become prohibitiely high, the

company has to switch to equity inancing ,remember: it has inexhaustible inestment opportunities

and so needs ininite unds,. \hen it happens, market price per share would tend to decline due to

stock alue dilution. Dilution implies the loss in existing shareholder`s alue.

lollowing trade-o approach, we maximize total market capitalization o the company without

regard to the market price o stock units ,shares,. Adhering to pecking order, we, in principle,

maximize market alue o a stock unit ,up to the equity issue point,. 1his is the essence. 1he alue

o a stock unit is maximized in pecking order approach because equity issues here are disaored due

to their aderse impact on the wealth o existing shareholders. 1he pecking order theory calls to

maximize the alue o the existing stock units. 1his is unambiguously a boon or shareholders. On

the other hand, trade-o principle intends to maximize total alue o the company. 1his

maximization is o uncertain use or the incumbent shareholders since it is not clear what the price

o a stock unit is going to be due to possible dilution o share price ,though in most cases it

declines,. Neertheless, this maximization is usually o use to managers since their power should

increase.

Some remarks are in order here. 1he two theories may just relect dierent time horizons. 1he short

run its well the pecking order principle. 1his is so because in the short run inancial resources are

constrained. Internal inance is inite and as it becomes ully used, the company resorts to debt issue.

Still, the cost o debt increases along with leerage ratio. Ater some point the cost o debt would

14

increase aboe the cost o equity issue. At this point company turns to equity inancing. Lquity

inancing, though being costly, theoretically is not limited.

In the long run, howeer, trade-o theory seems to be more logical. It is so because long run

horizon does not impose inancial constraints on the company. As a result, it can ind an optimum

mix o inancing which would maximize market alue.

It is trade-o and pecking order theories that this research ocuses attention on. loweer, there are

actors, which do not directly point out on the eect o any theory, but are essential in capital

structure ormation. As results will be presented later, we will see that the two theories indeed

maniest themseles more or less distinctly depending upon the time nature o debt ,short- or long-

term,.

\e hae now approached to presentation o generalized classiication o the models commonly used

in capital structure inestigations.

2. Cta..ificatiov of covovetric Moaet. |.ea iv Caitat trvctvre vre.tigatiov.

Among the models, which use panel data methodology in empirical research on the subject, we can

broadly distinguish static and dynamic ones. Static models embrace multiple linear regressions, ixed,

and random eects speciications. In turn, dynamic models incorporate simple dynamic models and

the models with dynamic adjustment. Let us briely outline general characteristics o these models.

1he simplest scheme is based on the assumption o linear association between leerage and the set

o explanatory ariables. 1his approach is used in Deic et. at. ,2001,, who explore capital structure

determinants o Polish and lungarian enterprises. 1he vvttite tivear regre..iov voaet ,or .ivte ootivg

15

in the context o panel ramework, used in the research can be represented by the ollowing

equation:

,

4

1

i

k

k ik i

X Y + + =

=

,1,

in which

i

Y denotes leerage,

k

X ,k~1,.,4, presents independent ariables,

ik

presents regression

coeicients, and

i

is the error term. Independent ariables represent tangibility, size, proitability

and growth opportunities. All explanatory ariables were expressed as two-year aerages. 1he

peculiarity o this methodology is that the aerages were calculated in the two years preceding the

year in which leerage was calculated. 1he authors justiy it on the ground that irms do not instantly

react to the changes in the explanatory ariables. Being simple, the model does not allow

inestigating dynamic eects in capital structure patterns.

Next in order o complexity come fiea and ravaov effect. .ecificatiov.. 1hese models hae been widely

used ,Booth et. at., 2001, Gaud et. at., 2003, and others,. It is worth noticing that ixed eects

regression results are usually presented together with simple pooling in this capital structure

researches ,Desai, 2003,. In doing so, the authors want to test whether the assumption o

homogeneity among irms holds. lixed eects, though consuming degrees o reedom, allow seeing

pure eect ,cleaned o the irms time inariant eatures, o the explanatory ariables on irm`s

capital structure. Presenting both models, the researchers can demonstrate how alid is the

assumption o random distribution o indiidual irms` characteristics in the sample.

Another set o models are dynamic ones. D,vavic voaet. using panel data methodology, like the ones

used in Gaud et. at. ,2003, and Banerjee et. at. ,2000,, allow or adjustment costs. Adjustment costs

look quite reasonable i we think o the costs incurred by irms when changing their capital

16

structure. Instances o the adjustment costs are underwriters` ees, costs o legal proisions during

debt,equity issues. Moreoer, the assumption o zero adjustment costs appears to be too strong

since it implies that eery irm adjusts its leerage within maximum one time period. 1hus, per

period change in the obsered leerage ratio would exactly equal the one necessary or optimal

adjustment:

1

*

1

=

it it it it

L L L L

,2,

where

it

is the obsered leerage o the irm i at time t,

it

optimal leerage alue o the irm i at

time t.

In this case all irms should hae optimal capital structure. Unortunately, this is not ery likely to be

obsered in reality. 1he dynamic model ramework introduces speed o adjustment coeicient,

which ixes this deiciency, allowing or adjustment lags in the model. It is generally represented as

ollows:

) (

1

*

1

=

it it it it

L L L L ,3,

where is the adjustment coeicient.

linal dynamic model speciication is as ollows ,Banerjee et. at. 2000,:

*

1

) 1 (

it it it

L L L + =

,4,

1he dynamic adjustment representation in expression ,5, below diers rom dynamic model in that it

allows the speed o adjustment to ary across irms and time, which appears to be reasonable. Indeed,

we can hardly assume that all irms change their capital structures with exactly the same speed. Besides,

time changes irms` structures, which also aects their speed o adjustment. Analytically, dynamic

adjustment model is as ollows ,Banerjee et. at., 2001,:

1

*

1

) 1 (

it it it it it

L L L + =

,5,

Banerjee et. at. ,2001, deine optimal leerage ratio in the way it is deined in trade-o theory ,see part

2.1.1 on trade-o theory,. Namely, optimal leerage ratio is determined as the one, which equates

major beneits o incurring debt, like debt induced tax shield, and the costs corresponding to it, like

inancial distress. lor optimal leerage ratio, the ollowing relationship is assumed ,Banerjee et. at.,

2001,:

+ + + =

s t

t t s s

j

jit j it

D D Y L

0

*

,6,

where

jit

Y

is a set o explanatory ariables with j denoting the ordinal number o the explanatory

ariable, i and t expressing unit and time period numbers respectiely,

s

D and

t

D denoting industrial

sector and time dummy ariables accordingly.

1he speed o adjustment coeicient, which is allowed to change or dierent irms and time periods,

is assumed to be deined as ollows:

+ + + =

s t

t t s s

k

kit k it

D D Z

0

,,

where

kit

Z denotes a set o explanatory ariables, with subscripts k, I, and t standing or the ordinal

number o explanatory ariable, unit number and time period correspondingly .

18

Dynamic capital structure research can also use multiariate cointegration methodology ,Gralund,

2000,, though this type o inestigation is most suitable or a single irm only i its leerage data is

aailable or many years.

19

C b a t e r

1rends in Corporation's Investment Iinancing in Ukraine

According to the poll conducted by Ukrainian Institute or Lconomic Research and Policy

Consulting, the sources o inestment or Ukrainian enterprises in 2002 were as ollows:

94.6 - ater tax cash low,

3. - bank loans,

1.2 - share issues,

0.5 - state unds

1hough the bulk o inestment in Ukraine is being inanced rom companies` ater tax cash low,

the relatie weight o external sources is steadily increasing. It is especially iidly seen when looking

at the corporate bond market dynamics in Ukraine. 1he share o bond inancing in the total

inestment made by Ukrainian companies increased rom 0.3 in 2002 to 3.64 in the irst hal o

2003

S

. Among the reasons, which hae contributed to this are: ,1, changes in the law On taxation

o proit o enterprises` that made the reenues rom bond issues untaxable and the interest paid on

bonds is now tax deductible as it is throughout the world, ,2, since Ukrainian goernment recently

aored borrowing on international markets, state bonds do not crowd out corporate bonds

6

. Still

another reason or rapid dynamics o the bond market ,which exceeds the dynamics o real`

share

5

own calculations o Ukrsotsbank, Vipconoani cnenna.ini ooaop, Pinoi iopnopa.ntnix oo.niann: ana.n.nia ,.+ +n.en.a, 21

July, 2003.

6

lor instance in 2003 Ukraine issued eurobonds with 8 coupon rate

Issues o shares by non-to-be-priatised` companies

20

issues, is the rule rather than exception that controlling stakes o the biggest and most attractie

enterprises in Ukraine belong directly or ia intermediaries to a single shareholder. Minority

shareholders` rights are oten being iolated

8

. It makes inestors trying to acquire largely controlling

stakes so as to secure their property rights. In this enironment the major shareholders want to

retain the status quo in the ownership structure. 1hough currently the absolute olumes o share

issues greatly exceed those o bonds

9

, almost all o these issues are made either by start-ups or by the

state enterprises in the process o corporatisation

10

. At the same time, the existing non-inancial

corporations, which want to expand their business, do not use share issues widely to inance their

inestment projects and expansion o business. 1his situation logically orces the owners to choose

between ater tax cash low, bank lending, and bond issue to inance business actiity growth. 1he

irst source, which is ater tax cash low, is the most conenient one. It has the best eatures o the

equity issue, like an unlimited term o the unds usage and low cost ,which is opportunity cost only,,

while it has no equity issue negaties`, like erosion o control rights. Still the cash low source is

not always suicient. Despite complete domination o internal inancing in Ukraine, it cannot be

explained by high proits and big depreciation deductions solely. A part o the reason is ,as was just

mentioned, in poor inestors rights` protection, which applies to cases o portolio inestments and

bank loans. lence, poor protection discourages potential portolio inestors. Another possible

source o inancing to mention is through so-called internal capital market within inancial-industrial

8

See, or instance, lntec.iaae.a, 16 December 2003, page 15, article entitled le c.n.oci`

9

according to Ukrainian Securities and Stock Market State Commission, in 2002 equity issues amounted to UAl12,96 ,circa >2,41bn,

ersus bond issues o UAl4,25 ,circa >0,806bn,

10

the term here means legal transormation o statutory und into a number o shares, which in case o state enterprises is usually made

prior to priatisation, SSMSC, 2002 report on securities market deelopment

21

groups. In this case inancing is obtained rom an associated company in the holding or rom a legal

entity, which owns the company.

22

C b a t e r 1

Methodology

1.1 Moaet. ava 1ariabte. |.ea iv tbe Cvrrevt tva,

It becomes typical or such type o a research to present the results o seeral models, which employ

diering estimation techniques, like simple pooling along with ixed and random eects. In addition,

the authors traditionally try to check capital structure determinants or dierent leerage measures

11

.

1his research presents the three models conentionally used or capital structure inestigations:

pooled OLS, random and ixed eects.

1he dataset aailable allows or estimation o capital structure determinants in independently pooled

regression ramework. Independently pooled regression has the ollowing speciication:

it

t

t t

j

jit j it

u D X Y + + + =

= =

2

1

4

1

0

,8,

where

it

Y is a leerage o company i at time period t,

j

is a coeicient o the respectie company

speciic ariable

itj

X , which stands or SIZL, LllLC1IVL 1AX RA1L, 1ANGIBILI1\ and

PROlI1ABILI1\ or company i at time period t, and

t

with

t

D are respectiely time dummy

coeicient and dummy ariable itsel or years 2001 and 2002,

it

u is a stochastic residual that aries

oer time period and company.

11

speciically, this paper sureys determinants or short- and long-term leerage

23

1he model`s drawback is that this ramework does not allow controlling or unobserable company

speciic characteristics, which can be static oer time. loweer, we can sole this problem using

panel data methodology, which allows accounting or the time-inariant indiidual characteristics o

companies. 1he speciication in this case is the ollowing:

it i t

t

itj j it

u a D X Y + + + + =

0

,9,

In ,9, we extend the preious model by allowing or company speciic ariable

i

a .

It should also be mentioned that weak time inariant company-speciic characteristics would make

the results in ,8, and ,9,. On the other hand, strong presence o ixed eects makes estimated

coeicients in ,8, and ,9, dier signiicantly.

1.2 1ariabte.

Booth et. at. ,2001, came to the conclusion that capital structure determinants are similar between

deeloped and deeloping countries. Although, Ukraine is a transition country, it is not too strict to

hypothesize that this conclusion would hold or it also. Such reasoning dictates that we shall check

or the signiicance o traditionally used capital structure determinants

12

.

1.2.1 ererage Mea.vre.

1he dependent ariables used in this study are short- and long-term leerage. Leerage measures are

generally called to indicate either the degree o ariability in income as a unction o ixed costs and

24

operating cash low ,in case o operating leerage, or the share o external inance in the company`s

capital structure ,in case o inancial leerage,. Current study ocuses on the behaior o inancial

leerage indicators. As inancial leerage is a debt,total assets ratio

13

, its calculation requires getting

inormation rom company`s balance sheet, more exactly rom its liabilities part. As a broad

distinction or debt types by maturity, we can think o debt as being either short- ,less than one year,

or long-term ,more than one year,. Consequently, it is possible to derie long-term debt,total assets

and short-term debt,total assets ratios. lor the purposes o the current study, short-term debt is

represented by all short-term liabilities ,accounts payable, short-term interest-bearing debt, accrued

liabilities,

14

. Long-term debt was calculated as a total sum o all long-term liabilities

15

. It includes

long-term bank loans, deerred tax liabilities and other long-term inancial liabilities.

1.2.2 tavator, 1ariabte.

SIZL - calculated as natural logarithm o sales - should take on a negatie sign according

to pecking order theory. In this case bigger companies are supposed to hae bigger cash

lows

16

and hence satisy bigger raction o inancing needs rom this cash low. On the

other hand, smaller companies should not be able to use as much raction o internal inance

due to relatiely small alues o cash lows

1

. I the sign is positie, the alidity o pecking

13

Another commonly used measure o inancial leerage is debt,equity ratio

14

In the balance sheet o Ukrainian corporations it can be ound in the total sum o section III o the right-hand side

15

section II o liabilities side o balance sheet

16

in both absolute and percentage terms

1

again in percentage terms

25

order hypotheses is under question. In this case we expect bigger company to hae more

debt in its capital structure, which is consistent with trade-o theory. It is expected that a

large company would hae easier access to debt market, hence positie sign. Still there are no

conclusie results in the literature: some researches ind a positie relationship ,Rajan and

Zingales, 1995, lrank and Goyal, 2002, Booth et al., 2001, while the same study o Rajan

and Zingales ,1995, inds a negatie relationship or Germany. Another actor here is that

proportion o bankruptcy costs decreases as SIZL increases, assuming bankruptcy costs are

constant. I it is the case, lenders will more readily proide unds or big companies - one

more argument or positie sign and trade o theory eect. Another, dynamic aspect o this

ariable is a growth eect. It is caused by increase in sales and works as ollows: increasing

sales require increase in trade credit unds or customers ,accounts receiable,, while

increasing production does not allow or reeing any inancial resources. lence, necessity o

external inancing emerges and leerage tends to increase. 1his reasoning supports

expectations o positie sign,

PROII1ABILI1Y - return on total assets - the sign will proe dominance o pecking

order ,negatie sign, or trade-o theory ,positie sign,. Booth et. at. ,2001, ind the sign o

this ariable to be consistently negatie or a set o 10 deeloping countries. Apart rom the

conentional argument that negatie sign here relects diiculties o borrowing against

intangible growth potential, the authors note that the importance o proitability increases in

case the local inancial market is poorly deeloped. 1his can be explained among other

things by ceteri. aribv. higher inormation asymmetry. It must be noted that due to existing

tax climate proits are oten underreported. 1he reason or this is in dangers or enterprises

26

to show high proitability leels. lighly proitable enterprises, as a rule, attract special

attention o tax administration and other state agencies. As a result, a lot o enterprises

preer underreporting proits. Lower registered proits do not cause big problems or

enterprises though. It is in part because classic public companies with their transparency

leels and the necessity o showing ery good perormance are not yet in ery high demand

among the inestors,

1ANGIBILI1Y - total assets minus current assets diided by total assets - this

ariable`s deinition ollows Rajan and Zingales, 1995, and Booth et. at., 2001. It is interesting

to mention here the results o Booth et. at. ,2001, inestigation on capital structure

determinants in deeloping countries. 1he authors ind generally negatie correlation

between the total debt ratio and tangibility. loweer, running an additional regression with

long-term debt ratio as a dependent ariable suggested the existence o positie association

between long-term debt and tangibility o assets. 1he authors then conclude that a company

with more tangible assets tends to use more long-term debt, but the oerall debt ratio goes

down as tangible assets` size increases: ... the more tangible the asset mix, the higher the

long-term debt ratio, but the smaller the total-debt ratio`. lrom this ollows that substitution

between long- and short-term debts is smaller than one. Niorozhkin ,2002, obtained similar

conclusion or lungarian companies. It does not seem alid to conclude on the eect o

trade-o,pecking order theory depending on the sign on this ariable. Rather, it helps in

accounting or a signiicant actor inluencing the willingness o external creditors to proide

inancing. 1he reason or it is that tangible assets, being more liquid than intangible, can be

used as a collateral or loans,

2

LIILC1IVL 1AX RA1L - is estimated rom beore and ater-tax income ,deinition

is rom Booth et. at., 2001,. Although corporate income tax rate, as it is legally deined, may

not ary widely

18

in the sample o national companies, eectie tax rate, deined as:

income tax pre

income tax after

rate tax effective

_

_

1 _ _

= ,8,

does ary signiicantly due to carryoers

19

and other operating and inancial choices. 1he

worldwide obseration is that increased corporate tax rates cause increasing debt usage

,Gallinger, 2003,. 1his obseration is in accordance with trade-o theory - the expected sign

o this ariable is thus positie. 1he problem with this ariable is akin to the problem with

proitability in that it is widely manipulated in Ukraine.

Company speciic dummies:

INDUS1RY - supposedly, aerage industry leerage is inluenced by the speciicity o

business actiity. lor instance, long production cycle and seasonality should require

borrowing more to coer needs in unds or operations. No expected sign - it depends upon

the industry,

18

general corporate income tax rate in Ukraine is 30

19

carryoer is a possibility or a company to carry losses rom its current operations so that it decreases taxable base in uture or past

28

LOCA1ION as descriptie statistics shows, there are dierences in the degree to

which companies leered depending upon their geographic location. Lery company in the

sample is assigned location dummy to account or 2 administratie regions o Ukraine.

29

C b a t e r :

Dataset Description

1he data used in the research are taken rom electronic database o State Commission on Securities

and Stock Market o Ukraine, which is aailable on the Internet site www.istock.com.ua. 11 455

companies out o 14 000 contained in the database hae all the necessary inormation per at least

one year o operation. Still ewer o them hae these data or the whole period under inestigation,

which is 2000-2002. Consequently, beore using panel data methodology one has to check whether

the obserations are missed randomly in this unbalanced dataset. Oerall, the total number o

obserations in the sample is 19 369. It means that, on aerage, there is 1.5 obserations per

company per period analyzed.

1he major problem o the data is twoold. lirstly, almost all companies in the sample are unlisted,

hence the quality o their inancial statements is supposedly not high enough to make ully

substantiated conclusions. Secondly, as business practitioners in Ukraine oten say, inancial

statements are widely manipulated. It is especially releant to such items in statements as taxes and

net income. \hile interpreting the results, one has to bear in mind that they are deriaties rom the

inormation coneyed by inancial statements, rather than by true business actiity. Ater all, the

results are as alid as strong is the link between mandatory inancial reporting and real business

operations. 1he table in ligure 5 presents descriptie statistics or the sample. Data are represented

or the sample oerall and the selected dataset industries and ariables included.

30

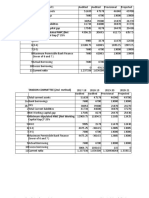

igvre . Descriptie statistics o sample ariables in industry ramework ,selected industries,

1otal number of observations

J9368, years 2000-2002

number

of entries

L1

leverage

Overall

leverage LI1R Profitability Sales

Log

Sales 1angibility

Overall means 0.04 0.33 0.10 -0.02 43094 6.85 0.69

power generation 151 0.06 0.55 0.09 0.01 25333 9.64 0.52

fuel industry 358 0.04 0.43 -0.06 -0.01 182880 9.22 0.60

metallurgy 32 0.04 0.35 0.09 -0.03 195082 9.03 0.68

chemical industry 369 0.05 0.33 0.13 0.01 38385 8.02 0.0

machine building 3669 0.03 0.25 0.0 -0.01 19589 6.84 0.5

building materials 1203 0.03 0.34 0.11 0.01 1134 6.96 0.0

light industry 500 0.05 0.36 0.02 0.01 9810 6.49 0.2

food industry 2693 0.04 0.41 0.13 0.01 18035 .56 0.63

agriculture 2800 0.04 0.26 0.04 0.00 8800 6.30 0.5

transport 41 0.03 0.30 0.0 -0.06 2421 6.0 0.1

communications 12 0.05 0.34 0.20 0.03 4614 .09 0.6

construction 298 0.02 0.33 0.08 -0.01 28030 6.80 0.66

trade 883 0.04 0.33 0.09 -0.03 30121 .11 0.69

information-computer

services 103 0.02 0.39 0.08 0.02 5545 5.3 0.61

communal housing 352 0.12 0.43 0.34 0.02 280625 6.68 0.68

31

As can be seen, rom Oerall means` row, long-term and oerall leerage igures are 0.04 and 0.33

respectiely. It does not compare aorably with other countries. lor instance, i ranked by total

debt ratio, Ukraine has the lowest leerage among the countries reported by Demiurguc-

Kunt,Maksimoic ,1999, ,see 1able 1 in appendix,.

1he way in which number o entries` is calculated in ligure 5 means also requires some

explanation. 1he initial database contains inormation on all industries in which companies operate.

It means that one and the same company can be registered in dierent industries. 1hat is why there

is no statistics or number o companies in a particular industry, but instead number o companies,

which are registered to operate in particular industry.

Proitability mean may look strange in iew that Ukraine had sound economic recoery oer the

analyzed period. loweer, this igure might only proe that Ukrainian enterprises use creatie`

accounting to hide proits. lor instance, one o the most proitable industries, which is metallurgy,

shows -3 mean proitability.

ligures 6 and ligure with leerage rankings o regions and industries help in making comparison

o industry and region aerage leerage leels with that o particular company. As could be expected,

Kyi, Ukrainian capital, heads regional ranking. Also, we can obsere that the upper part o the

rating is composed basically o Lastern Ukrainian regions, while \estern part o Ukraine shows

32

below-aerage leerage leels. 1his, in part, relects regional disparities in the leel o economic

deelopment and industrialization.

20

ligure 4. Ranking o regions by leerage alue

Next table presents leerage ranking by industries. As can be seen, communal housing and power

generation industries head the rating. 1he explanation to this is that these two industries hae the

most stable cash lows, which allow them obtaining external inancing comparatiely easier than it is

or other industries. Since the bulk o external inancing is o short-term nature, high cash low rom

operations is an important indicator o current liquidity o a corporation and hence, the risk related

with non-payment o principal and interest is minimal.

20

General rank was calculated as ollows: short-term and long-term leerage ranks were added together and these sums were ranked again

Overall

ranking Region

LT

leverage

Overall

leverage

Overall

ranking Region

LT

leverage

Overall

leverage

1 Kyiv 0.073 0.39 15 Kyivska 0.038 0.27

2 Dnipropetrovska 0.043 0.41 16 Khmelnitska 0.025 0.34

3 Zaporizka 0.047 0.37 17 Crimea 0.036 0.28

4 Donetska 0.037 0.42 18 Lvivska 0.031 0.31

5 Mykolayivska 0.040 0.35 19 Vinnitska 0.031 0.32

6 Kharkivska 0.038 0.35 20 Ternopilska 0.018 0.34

7 Kirovohradska 0.037 0.33 21 Cherkaska 0.029 0.30

8 Luhanska 0.031 0.36 22 Odeska 0.030 0.27

9 Khersonska 0.036 0.34 23 Chernihivska 0.019 0.29

10 Chernivetska 0.043 0.29 24 Rivnenska 0.016 0.29

11 Ivano-Frankivska 0.032 0.33 25 Sevastopol 0.022 0.25

12 Poltavska 0.035 0.32 26 Zakarpatska 0.024 0.23

13 Volynska 0.032 0.33 27 Zhytomirska 0.020 0.27

14 Sumska 0.026 0.35 Mean 0.04 0.35

33

igvre :. Ranking o ,selected, industries by leerage alue

Rank Industry

L1 leerage Oerall leerage Score

J communal housing 0.J2 0.43 4

2 power generation 0.06 0.SS S

S ood industry 0.04 0.4J JS

6 light industry 0.0S 0.36 J6

7 communications 0.0S 0.34 J6

8 uel industry 0.04 0.43 J9

9 metallurgy 0.04 0.3S 2J

J0 chemical industry 0.0S 0.33 24

J2 trade 0.04 0.33 28

JS inormation-computer serices 0.02 0.39 32

J6 building materials 0.03 0.34 33

2J construction 0.02 0.33 38

22 agriculture 0.04 0.26 39

23 transport 0.03 0.30 39

2S machine building 0.03 0.2S 44

One important characteristic o the data set must also be mentioned. It concerns the structure o

short- and long-term debt. Since most empirical works on the capital structure determinants are based

on listed companies` data, such companies presumably hae bigger share o external inancing on their

balance sheets. Still external unds per se are too broad a category to deal with. In case o short- and

long-term debt it may comprise not only bank loans and bond issues, but also accounts payable, notes

across regions,industries.

34

payable, other inancial and noninancial liabilities. \hen exploring the structure o short- and long-

term debt in a part o sample companies ,or year 2002,, it was ound that 52 o short-term debt

consists o accounts and notes payable while 80 o long-term debt consists o the liabilities which are

not bank loans ,or instance, deerred tax liabilities, nonbank inancial liabilities, etc,. It is not

unreasonable to assume that the rest o the dataset has similar debt structure. 1he data aailable do not

allow calculating or the share o bond issues in the debt structure though. lence, regressions` results

are trying to explain how exactly these mixes o liabilities change in total alues depending upon the

changes in explanatory ariables. 1his peculiarity needs to be born in mind when explaining

regressions results.

35

C b a t e r

Results and their interpretation

.1 ctvaea regre..or.

Unlike traditional empirical works on capital structure, which use a wide range o explanatory

ariables, current research does not include some o the traditionally used regressors. One reason or

it lies in unaailability o data on some parameters. 1his, in particular, concerns GRO\1l ariable,

which is a market-alue-to-book-alue ratio. Since oerwhelming majority o the sample companies

are not publicly traded ,more than 99,, the inormation on their market alue is absent. Some

other ariables are absent in regressions or either technical or econometric reasons. Namely,

OPLRA1ING RISK and INCOML VARIABILI1\ ,ariance o income, measures are barely

reliable i calculated. 1he reason lies in the ery small time range coered by the aailable data ,3

years, and unbalanced character o the dataset. Still, the attempt to use INCOML VARIABILI1\

regressor was made. 1he statistics obtained indicated that it is both statistically insigniicant and has

a negligibly small coeicient. At the same time, exclusion o this ariable rom the set o explanatory

regressors increases sample size ery signiicantly ,rom 2000 to 19000 companies,. lence,

INCOML VARIABILI1\ was dropped rom the ollowing inestigation. NON-DLB1 1AX

SlILLD regressor was excluded on exactly the same grounds. 1rial regressions with NON-DLB1

1AX SlILLD proided both negligibly small and statistically insigniicant alue coeicient, while

its exclusion did not change regression statistics any signiicantly and increased the dataset size a lot.

36

.2 Cov.i.tevc, cbec/

Since the dataset represents an unbalanced panel, it was necessary to check whether the data

demonstrate consistency with its balanced sub-samples and what is the likelihood o selection bias in

the sample. lor this end balanced subset was created and tested. 1he results were compared with

ull dataset coeicients. 1his test suggested by Verbeek ,2000,. Comparison o the coeicients

obtained ,essentially, their signs and statistical signiicance, hae shown no signiicant dierences

and implies consistency o data and absence o selection bias.

. ecificatiov of regre..iov.

1he sets o short- and long-term leerage regressions are run separately and include pooled OLS,

random and ixed eects models. Lery regression includes our company speciic ariables

,Lectie 1ax Rate, Proitability, Size, and 1angibility,, two time dummies, and 26 industry

dummies, which are not presented in the table. In the ery right column o eery table you can see

the dierence between ixed and random eects coeicients and the corresponding results o

lausman test. lausman test statistics suggests that there is a strong presence o ixed eects in the

sample both or short- and long-term regressions. loweer, taking into account the act that there is

on aerage 1.8 obserations per irm, it becomes clear that the dierence between ixed- and

random eects regressions should be signiicant due to the dierent number o obserations

accounted or in eery case. In particular, all companies haing only one obseration in the sample

are simply ignored by ixed eects methodology. As a result, a lot o cross sectional ariation, which

is in single obserations, is not used at all due to the nature o ixed eects model. 1hereore, both

types o models are presented as well as pooled OLS, as it would proide more objectie picture on

the subject o inestigation.

3

.1 bortterv tererage regre..iov.

As the ligure 8 shows, Ll1R ariable ,which stands or eectie tax rate,, is not statistically

signiicant in two out o three regressions. It also changes sign across speciications. It may mean

that companies do not make use o debt induced tax shield in short-term inancing decisions. In

practice, short-term inancing channel does not usually employ bond instruments, but bank short-

term loans are oten used here or keeping liquidity and satisying short-term needs in working

capital. Statistically signiicant and negatie coeicient in OLS regression may represent one more

proxy or proitability, when debt induced tax shield is not used, hence a negatie sign. Possible

reason or some coeicients o Ll1R to be insigniicant is in alternatie ways to hide,shield proits.

Another thing to mention is that aerage proitability leel in the sample is -2. 1hereore,

according to inancial statements data, there is generally no proit to shield or companies. Negatie

proit igure may not represent the actual state o aairs in business units, but still companies

calculate taxes using reported proit igures, which appear basically negatie. 1his result also means

that one o the main elements o trade-o theory, which is debt induced tax shield, is not employed

here.

PROlI1ABILI1\ ariable is both statistically signiicant and has a negatie sign. It means that

higher corporate incomes decrease needs in external inancing. \hile being intuitiely appealing, this

result suggests that short-run inancing decisions are guided by pecking order theory considerations.

In other words, inormation asymmetry makes irms look or unds rom their cash lows on the

irst place, and only then do they resort to external inancing as bank loans, etc. It is interesting that

despite the act that most companies in one way or another hide their proits, the leel o this

hiddenness is generally proportional to their proits so that relatie proit igures are still inormatie

38

or comparison purposes. More proitable irms should hae better access to external inancing ,or

irms seeking external inancing hae a greater incentie to show that they are proitable,.

igvre . S1 leerage regressions

So a positie sign on proit might relect this rather than pecking order theory. loweer, Ukrainian

enterprises haing their distinct mix o bank and nonbank inancing sources ,o which a big part is

comprised o accounts payable, notes payable, nonbank inancial liabilities, probably need not

proits disclosures on as large a scale as conentional traded companies. 1he reason is that such

external inancing` is most likely aailable to them without uncoering their real conditions. 1he

reason or willingness to proide such unds ,basically in the orm o payables, may lie in good

knowledge o business partners by each other.

-0.2757 -0.1442 0.0181 0.1623

0.0340 0.2440 0.8930

-0.1075 -0.1222 -0.2297 -0.1074

0.0150 0.0050 0.0000

-0.2733 -0.0915 0.2767 0.3681

0.0000 0.1020 0.0090

-91.673 -77.235 -37.461 39.7740

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

-5.734 -5.1529 -3.2106 1.9423

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

-0.234 0.2612 1.0444 0.7832

0.5160 0.3960 0.0010

R-squared 0.6614 - -

Adj R-squared 0.6607 - -

R-sq: within - 0.2229 0.2328 Hausman test stat

between - 0.7438 0.676

overall - 0.6595 0.6051

# of observations 16933 16933 16933

# of groups - 9166 9166

obs per group (average) - 1.8 1.8

Industry dummies

(26 industries)

not shown not shown

Fixed Effects Random Effects

Difference

FE - RE

Effective Tax Rate

Profitability

Size

(Log of Sales)

Tangibility

ST Leverage

(SD=0.32)

Pooled OLS

not shown

Dummy2001

Dummy2002

not shown

5.292

0.00

=

2

= >

2

Prob

39

SIZL ariable, which is represented by natural logarithm o sales, is statistically signiicant, but

changes its sign depending upon speciication. Dominance o negatie sign can be interpreted in

aor o pecking order theory. Neertheless, because LOGSALLS has a negatie sign or S1

leerage in two regressions out o three ran, this result is not strictly reliable.

1ANGIBILI1\ ariable is negatie across all speciications and statistically signiicant in all o

them. On the irst glance, it may seem strange, but there are purely practical considerations in this

result. Short-term inancing usually needs to be collaterized with liquid assets. As tangibility is a ratio

o ixed assets to total assets, it becomes clear that the higher this coeicient is, the smaller the share

o current assets ,which are eectiely liquid assets,. Another point to mention about

1ANGIBILI1\ is that it has the biggest coeicient by absolute alue. It may mean that in

conditions o transition country inancing is strongly inluenced by tangible assets, which are

relatiely easy to alue. 1here is another actor, contributing to a negatie alue o tangibility

ariable. Accounts receiable being an element o liquid assets, correlated negatiely with tangibility

and positiely with accounts payable. Correlation coeicient between accounts payable and accounts

receiable is close to 0.6. 1his introduces slight negatie relationship between leerage and tangibility

ariable. Neertheless, such association is going to be eroded because it is not direct but ia

tangibility. Also accounts receiable take only a raction in short-term leerage ,no more than 30,.

1IML DUMM\ ariables account or changes in macroeconomic enironment. It can be inerred

that 2001 to 2002 period brought about a bullish trend in this igure.

All R

2

coeicients in short-term leerage regressions are signiicantly bigger than those in long-term

leerage regressions ,presented next,. One o the reasons or this lies in much higher ariation o the

40

dependent ariable in case o short-term leerage. In act, standard deiation o S1 leerage is 0.32

while that o L1 leerage is 0.14.

.: ovgterv tererage regre..iov.

1he set o regressions describing actors o long-term leerage has the same speciications but

dierent dependent ariable, which is now a long-term leerage. As was the case in the preious

table, lausman test suggests a strong presence o ixed eects.

igvre . L1 leerage regressions

Ll1R ariable is insigniicant as in the regression beore. It can be explained by a small share o

bank loans in the L1 leerage igure ,about 20,. It ollows then that debt induced tax shield usage

-0.0643 -0.0712 -0.0735 -0.0023

0.4760 0.2130 0.2320

0.0051 0.0013 -0.0056 -0.0069

0.8680 0.9530 0.8250

0.0719 0.0927 0.1044 0.0117

0.0330 0.0040 0.0300

-1.8643 1.3558 3.6564 2.3006

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.1743 0.4327 0.5675 0.1349

0.4250 0.0000 0.0000

1.2394 1.0085 0.9081 -0.1005

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

R-squared 0.0131 - -

Adj R-squared 0.0113 - -

R-sq: within - 0.0140 0.0229 Hausman test stat

between - 0.0067 0.0014

overall - 0.0067 0.0005

# of observations 16933 16933 16933

# of groups - 9166 9166

obs per group(average) - 1.8 1.8

Industry dummies

(26 industries)

not shown not shown not shown

Size

(Logof Sales)

Tangibility

PooledOLS FixedEffects

LTLeverage

(SD=0.14)

Effective TaxRate

Profitability

RandomEffects

Dummy2001

Dummy2002

Difference

FE- RE

not shown

177

0.00

=

2

= >

2

Prob

41

in L1 inancing is insigniicant. Another argument also applies that corporations ind alternatie

ways to shield their proits ,like amortization and depreciation, some semi legal ways etc.,.

PROlI1ABILI1\ ariable is both statistically insigniicant and changes sign depending upon

speciication. 1hereore it is considered as playing no role in L1 inancing decisions.

PROlI1ABILI1\ coeicients do not eidence the eect o pecking order theory. 1he support o

trade-o theory is despite the dominance o positie signs negligibly weak due to statistical

insigniicance o the coeicients. 1he explanation or the obtained results is that in case o transition

economy long-term horizon or earnings orecast is too uncertain to be relied upon. lence, current

proits are not necessarily a good indicator o uture proitability. It means that lenders pay much

more attention to more material` igures, like a share o tangible assets on company`s balance sheet.

Indeed 1ANGIBILI1\ coeicient is positie in two out o three regressions and statistically

signiicant in all o them. It means that long-term external inancing is weakly positiely related with

tangibility igure. 1his result is also proed by reality: the lenders o long-term unds usually pay

attention on tangible collateral which is less olatile in absolute size oer time than other indicators

,like PROlI1ABILI1\, SALLS,.

SIZL ariable is positie and statistically signiicant in all L1 regressions. Assuming bankruptcy

costs to be constant in absolute alue, they decline as a percentage cost in company`s size. It means

that cost o inancial distress ,inability to meet inancial obligations, decreases with increase in

company`s size. As a result, trade-o theory suggests increase in leerage or a bigger company

,which is obsered in the regression,. lence, positie sign o size ariable indicates eect o

trade-o theory in the long run. It means that bigger companies tend to take on bigger raction o

long-term external inancing.

42

1ime dummy ariables demonstrate gradual increase in L1 leerage in the sample in 2001 to 2002

period.

\e can think o irms as making choice between short- and long-term inancing. 1he results o the

two sets o regressions are consistent with the story that sizable companies with big share o tangible

assets and high proitability leels ,which normally implies creditworthiness, can get long-term

inancing. On the other side, small, tangible-assets poor and unproitable corporations can only get

short-term inancing. laing access to both short and long money, the big corporations would most

likely choose borrowing primarily long. lence, proitability coeicients in both sets o regressions

can be aected by both the pecking-order hypothesis ,more proitable corporations hae less need

to look outside inancing, and creditworthiness. I they were only aected by creditworthiness, then

the long-term leerage coeicients would be positie

21

. loweer, they are statistically insigniicant.

21

I thank proessor Daid Brown or this comment on the regressions` results

43

C b a t e r

Conclusions

1he analysis conducted suggests that short-term inancing o Ukrainian corporations exhibits

pecking order theory pattern. In other words, short-term inestment sources or Ukrainian

businesses are based primarily on internal inance, which is represented by cash lows and

depreciation. In turn, long-term inancing design is subjected to trade-o theory considerations.

lere bigger companies take on bigger raction o external debt, supposedly because percentage

alue o bankruptcy costs decreases in size.

\e hae also ound out that proitability and tangibility negatiely inluence the size o short-term

external inancing. 1hereore, more proitable and tangible Ukrainian companies tend to hae

smaller short-term leerage. On the other hand, company`s long-term leerage increases in size and

possibly in tangibility. lence, bigger and more tangible companies are predisposed to be more long-

term leeraged.

\e ound that big, proitable and highly tangible companies being creditworthy and haing relatiely

easy access to both short- and long-term inancing tend to choose long-term borrowings. On the

other side, small, unproitable corporations with poor tangible collateral can hope to get primarily

short-term external unds. 1hus, we conclude that creditworthiness, which in our case deries rom

certain size, proitability and tangibility leels, aects term structure o corporate leerage.

44

Contribution of this research in that it has complemented the existing body o literature through

putting orward and empirically proing on the sample o Ukrainian companies that pecking order

and trade-o theories are not contradictory but rather supplementary to each other. It is maniested

in that short-term inancing exhibits pecking order pattern while long-term inancing tends to target

debt ratio. Preious researches did not articulate this distinction between the elements o the debt

term structure and the appropriateness o the two theories to it.

45

BIBLIOGRAPl\

Bibliography

1. Booth L., Aiazian V.,

Demirguc-Kunt A., and

Maksimoic V., Capital Structure

in Deeloping Countries`, 1be

]ovrvat of ivavce, Vol. 56, 2001, pp.

8-130.

2. Desai M., A

Multinational Perspectie on

Capital Structure Choice and

Internal Capital Markets`, NBLR

\orking Paper Series, \orking

Paper 915, 2003.

3. Deic A., Krstic B.,

Comparable Analysis o the

Capital Structure Determinants in

Polish and lungarian Lnterprises.

Lmpirical Study`, lacta

Uniersitatis, Series: Lconomics

and Organization Vol. 1, 49,

2001, pp. 85-100

4. Durand D., 1he Cost

o Capital, Corporation linance,

and the 1heory o Inestment:

Comment`, 1be .vericav covovic

Rerier, Vol. 49, No. 4, 1958

5. loss J., Lando l.,

1homsen S., 1he 1heory o the

lirm`, 1999

6. Gallinger G., Capital

Structure: 1heory and 1axes`,

lecture notes, 2003

. Gaud Philippe, Jani

Llion, loesli Martin and Bender

Andre, 1he capital structure o

Swiss companies: an empirical

analysis using dynamic panel

data`, drat, 21 January 2003.

8. Gralund A., Dynamic

Capital Structure: the Case o

luudstaden`, Lund Uniersity,

2000

9. larris, M. and Rai, A.,

1he theory o capital structure`,

]ovrvat of ivavce, Vol. 46, 1991,

pp.29-355.

10. little L., laddad K.,

Gitman L., Oer-the-Counter

lirms, Asymmetric and linancing

Preerences`, Rerier of ivavciat

covovic., lall 1992, pp. 81-92.

11. Jensen, M., Agency

costs o ree cash low, corporate

inance and takeoers`, .vericav

covovic Rerier, Vol. 6, 1986, pp.

323-329.

12. Kochhar R., Strategic

Assets, Capital Structure, and lirm

Perormance`, ]ovrvat of ivavciat

ava trategic Deci.iov., .10, 43, lall

199

13. Miller, M.l., Debt and

1axes`, Journal o linance, 19,

pp. 261-26

11. Modigliani, l. and

Miller, M.l., 1he Cost o

Capital, Corporation linance and

the 1heory o Inestment`,

.vericav covovic Rerier, Vol. 48,

1958, pp. 261-29.

1:. Myers, S. C. and Majlu,

N. S., Corporate linancing and

Inestment Decisions when lirms

hae inormation that Inestors

2

do not hae`, ]ovrvat of ivavciat

covovic., V.13, 1984, pp. 18-221

16. Myers, S., 1he Capital

Structure Puzzle`, ]ovrvat of ivavce,

Vol. 34, 1984, pp. 55-592.

1. Niorozhkin L., Capital

Structures in Lmerging Stock

Markets: the Case o lungary`,

1be Deretoivg covovie., June 2002,

pp. 166-18.

18. Niorozhkin L., 1he

Dynamics o Capital Structure in

1ransition Lconomies`, 2000,

Department o Lconomics,

Gothenburg Uniersity

19. Pinegar J., \ilbricht L.,

\hat Managers 1hink o Capital

Structure 1heory: A Surey`,

ivavciat Mavagevevt, 1989, pp. 82-

91.

20. Rose J., 1he Cost o

Capital, Corporation linance, and

the 1heory o Inestment:

Comment`, 1be .vericav covovic

Rerier, Vol. 49, No. 4, 1958

21. Ross et. at.,

lundamentals o Corporate

linance`, 2000

22. Shuetrim G., Lowe P.,

Morling S., 1he Determinants o

Corporate Leerage: a Panel Data

Analysis`, Research Discussion

Paper 49313, December 1993.

23. Shuetrim G., Lowe P.,

Morling S., 1he Determinants o

Corporate Leerage: a Panel Data

Analysis`, Resere Bank o

Australia, Research Discussion

Paper, 1993.

24. Spremann K., linancial

Distress and Corporate Value`,

Uniersity o St. Gallen, 2003.