Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

The American School of Classical Studies at Athens

Cargado por

Danilo Andrade TaboneDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

The American School of Classical Studies at Athens

Cargado por

Danilo Andrade TaboneCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

The Nikopolis Project: Concept, Aims, and Organization Author(s): James Wiseman and Konstantinos Zachos Source: Hesperia

Supplements, Vol. 32, Landscape Archaeology in Southern Epirus, Greece 1 (2003), pp. 1-22 Published by: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1354044 . Accessed: 24/10/2011 14:06

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The American School of Classical Studies at Athens is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Hesperia Supplements.

http://www.jstor.org

CHAPTER

THE

NIKOPOLIS AIMS,

PROJECT: AND

CONCEPT,

ORGANIZATION

byJames Wiseman and Konstantinos Zachos

Human societies at all times and in all parts of the world interact with the landscape they inhabit: it could not be otherwise, even if the interaction were somehow limited to the selective exploitation of natural resources. Human activities alter the landscape and the natural environment, often in dramaticways; the alterations may occur as the result of human design, as in clearing a forest to plant crops, or may be incidental, as in the destruction (or reshaping) of a mountainside by Roman miners of precious metals. Conversely, humans at various times in the past have physically adapted to changes in their environment (especially in the distant past), or responded to environmental change in a variety of other ways. Some of these responses, such as migration or technological innovation, have been drastic and revolutionaryin their effect and are often recognizable in the archaeologicalrecord,while other responseswere more gradual,even subtle, and are more difficult to detect. To acknowledge the importance of the natural setting, of the environment at large, in studying change in human society is not to deny the importance of interculturalrelationships, or the role of the individual intellect or collective social conscience in the evolution of ethical, spiritual, or other sociocultural phenomena in human affairs.The point is that to understand and explain changes in human society over time, it is critically important to study society in relationship to the changing environment in which it existed. Through this approach to the past archaeologists are able to provide insights into the factors that underliechanges in human-land relationships,sometimes over a short timespan or even regarding specific events, but especially over the long term. And they can explore those intercultural relationships and sociocultural phenomena cited above, which themselves evolve within specific environmental settings and change. We have sought to apply these concepts in the formulation and conduct of the Nikopolis Project, an undertaking in landscape archaeology focused on the human societies that inhabited southern Epirus in northwestern Greece from earliest times to the medieval period. More specifically, the project has employed intensive archaeological survey and geological investigations to determine patterns of human-activity areas, and

JAMES

WISEMAN

AND

KONSTANTINOS

ZACHOS

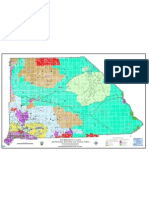

Figure1.1. Map of Epirusand adjacent regions.The surveyzone is indicatedby crosses. what the landscape and other features of the natural setting were like in which those activities took place, in an effort to understand and explain observed changes in human-land relationships through time.1

THE CHOICE STUDY

OF SOUTHERN

EPIRUS FOR THE

Southern Epirus was selected for this broad diachronic study in part because, at the time, it was only in Epirus and in Thessaly that there was material evidence for something approaching the full range of prehistoric periods. Palaeolithic stone tools, for example, were first attested in Greece in the Louros River valley of Epirus.2 The area is also topographically diverse, including coastal regions, marshy lagoons, inland valleys, high upland plains in rugged mountain terrain, and mountain passes,3thereby providing a variety of environmental settings for different types of human activities that might be investigated by the project.What is more, prior to the Nikopolis Project there had been no large-scale, systematic, modern survey of the region, and most of the previous archaeological excavations were limited in a variety of ways.4The Nikopolis Project thus could be expected to enlarge our knowledge of a region that was not well known archaeologically. Another important considerationwas the existence in the surveyzone of Nikopolis, the "city of victory" founded by Augustus to celebrate his

1.This introductory section an is version the statement of of expanded

aims set out in Wiseman 1995a, p. 1, and uses some of the phrasingof that earlierformulation. 2. Dakaris,Higgs, and Hey 1964; Higgs and Vita Finzi 1966; Higgs et al. 1967. 3. Etudegdologique. 4. See below,"Previous Archaeological Work in the SurveyZone."

THE

NIKOPOLIS

PROJECT

3

I

*..11,-

Louros River

Acheron River

,~~\ ~

, Parga ,Kiperi Phnr^ . (Ammoudia Ephyra Vouv taos

f Voulista

~ ~Panayia

Yeoryios Ayios Thesprotiko Kastri kinopilos 'N2manteion KastroRizovouni , *Spilaion \ *Loutsa Aloaki. V Ch mLadiouros .:- dio Rogo, i;':: Palaiorophoros? Louros-Kastro ' / -' - :, Arachthos Cassope* ) '"X * Strongyli \ River K'

Kastkrosykm Grammeno Archan los

IC mian Sea

*1o

Nikopolis

Chlts .Tmas

SaIaor

OrmosVathy

y7."\ Prey .a ;:, Actm

Ambracian Gulf

Figure1.2. Map of surveyzone with selectedtoponyms

10

15

20

25 KM

..:.

victory in 31 B.C. over Antony and Cleopatra in the Battle of Actium. The creation of the urban population by the officially encouraged migration or forced removal to Nikopolis of populations from other cities of Epirus, Acarnania,Leucas, Amphilochia, and Aetolia,5 and the long life of Nikopolis as the metropolis of Epirus, raised a number of challenging problems regarding the relationship between the city and its territory to which the project'sresearchconcepts were directly applicable.The project thus takes its name from Nikopolis, the best-known toponym in southern Epirus. Finally, there was an urgent need for interdisciplinary survey before certain types of evidence, including some of the culturalremains, vanished as a result of various activities:land reclamation near the coast, the growth of the modern town of Preveza and several other smaller communities, industrial and agriculturaldevelopment, limestone quarrying,and other development activities related to tourism. These activities had wrought major changes on the regional landscape since 1950, and the pace of change in recent years had accelerated.

THE SURVEY ZONE

5. Kirsten(1987), Murrayand Petsas (1989, pp. 4-5), and Purcell (1987) all discussthe founding of Nikopolis and cite the most important sources.

The survey zone (Figs. 1.1, 1.2), about 1,200 km2, includes the entire nomos (administrativedistrict)of Preveza,a modern town on the Nikopolis peninsula, extending from the straits of Actium almost to the walls of the ancient city. On the east the survey zone extends into the nomos of Arta,

JAMES

WISEMAN

AND

KONSTANTINOS

ZACHOS

so that the entire deltaic, lagoonal area of the Louros River after its exit from its gorge at the modern town of Philippias was included; not included was the course of the Arachthos, a larger river east of the Louros which flows through the city of Arta (the ancient Ambracia) before emptying into the Ambracian Gulf, also known today as the Gulf of Arta. It is the western part of the north coast of the gulf, therefore, that lies within the surveyzone, from Salaoraon the east to the southerntip of the Nikopolis peninsula. The other boundaries follow those of the nomos of Preveza. That is, the western boundary of the survey zone is the shoreline of the Ionian Sea, from the straits of Actium on the south, where the Ambracian Gulf is linked to the sea, extending north beyond Ammoudia Bay (= Phanari Bay), at the mouth of the Acheron River, to Parga.The northern boundary of the survey zone runs east from Parga, along the middle Acheron River, and across the mountains to the narrowsof the Louros River gorge near the modern town of Kleisoura, below the ancient acropolis known locally as Voulista Panayia. The geology and geomorphology of southern Epirus are discussed in detail in Chapters 3, 5, and 6, so comments here are limited to observations of an introductory nature, primarily focusing on features providing general constraints on communication and exploitation of resources. A series of north-south Mesozoic limestone ridges, 600-1,000 m high, extends across the region from the Louros gorge to the Ionian coast, alternating with Tertiary flysch basins at elevations of 150-600 m, so that the basins provide now, as they did in the past, corridors of varying convenience for traveling north-south; fortified town sites of Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic times are situated along the routes. Access to these natural corridors on the south is via passes through or between a series of mountains along the Ambracian embayment: from west to east, Mts. Zalongo, Stavros, and Rokia (see Fig. 5.1). The Louros River valley was an important communication route from early prehistoric times to the present; the principal road from Arta to Ioannina, present-day capital of Epirus, still passes through the gorge. The next basin on the west is most easily entered from the south between Mts. Rokia and Stavros, and a travelerwould pass near a fortified Classical and Hellenistic town site (Kastro Rizovouni) en route to the north and the passes that lead eventually into the valley of Dodona. The next basin to the west includes access to the upper Acheron River, and can be entered over a low ridge between Mts. Stavros and Zalongo. A bit furtherwest, the naturalroute is over a ridge of Mt. Zalongo, by the Classical and Hellenistic town of Cassope, and from there through a winding pass to the modern town of Kanallakion in the eastern part of the plain of the lower Acheron River. Agriculture is now practiced throughout the region, wherever it is possible to do so, in the upland valleys, along the courses of rivers and streams, and in the coastal areas. In the latter regions, especially around Ammoudia Bay and along the north coast of the Ambracian Gulf, swamps and marshyareashave been drainedduring the past half-century and flooding has been further controlled by the construction of canals, which also serve as conduits for irrigationof fields. Dams were built on both the Louros and Arachthos Rivers.There has been extensive work also in some of the

THE

NIKOPOLIS

PROJECT

upland basins; for example, a small lake (Lake Mavri) was drained in the basin east of Kastro Rizovouni to provide more arableland, and the deep waters of Lake Ziros in the same area are now being tapped for irrigation. The whole lower Acheron and the valley of its chief tributary,the Vouvos (ancient Kokytos) River,as far as the modern town of Paramythia(outside the survey zone) are now lush with vegetation, including a variety of cash crops and orchards.

PREVIOUS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY ZONE

WORK IN THE

account previous of 6. A detailed

investigationsin southernEpirus is

beingprepared K.Zachos. by

7. Dakaris 1971, 1975b, 1977,1978, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983. 8. Dakaris 1958, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1975a, 1975b, 1977, 1993; Wiseman 1998. 9. Dakaris,Higgs, and Hey 1964; Higgs and Vita-Finzi 1966; Higgs et al. 1967. 10. Bailey et al. 1983a, 1983b; and Bailey,Papaconstantinou, Sturdy 1992. The investigationsin Epirusby

The most significant archaeologicalactivities in the largerregion in earlier years6were excavationsby Greek and German scholars at the ancient town of Cassope;7 Greek excavations at a site near the mouth of the Acheron identified by the excavatoras the Nekyomanteion, the Oracle of the Dead;8 and investigations by British scholars of Palaeolithic sites in the Louros River gorge to the northeast of Nikopolis.9 Recently the British renewed their interest in some of Eric Higgs's early work at Kokkinopilos and its environs (e.g., Asprochaliko),and carriedout limited surveyfor Palaeolithic remains along the coast.10Little was known of Neolithic, Bronze Age, and early Iron Age developments in the region, but the historical period was somewhat better represented in the scholarly literature.Important, useful studies of the region in antiquity were published by N. G. L. Hammond11 and by Sotirios Dakaris.12Both authors included copious topographical observations in their books and their researchinvolved some survey,which was, however, neither systematic nor intensive. Other archaeological investigations in the area have been limited to small-scale operations, usually involving salvageor preservationby the ephoreias,and have been briefly Deltion of the Greek reported over the years in the annualArchaiologikon Archaeological Service.

BACKGROUND PROJECT

AND ORGANIZATION

OF THE

as G. Bailey his colleagues, wellas and otherrecent worksomewhat further afield(e.g.,by K.Petruso Albania), in arediscussed, additional and publicationscited,by Runnels vanAndel and

in Chapter3. 11. Hammond 1967. 12. Dakaris 1971, 1972. 13. Paperspresentedat the symposiumwere publishedin Chrysos 1987. 14. Wiseman 1987, p. 413.

The Nikopolis Project had its origins in the First International Symposium on Nicopolis in 1984.13A paper presented by one of us (JW) focused on the need for the study of Nikopolis in its topographic setting, and suggested approachesto such a study.One specific recommendation, particularly relevant to the eventual development of the Nikopolis Project, was phrased as follows. A survey both of the naturalresources and the cultural remains of the region will be required if Nikopolis is to be studied in its regional context. What is more, the ancient topographic profile, including the changing coastlines, must be determined, along with climatic changes and the palaeoecology generally.14

JAMES

WISEMAN

AND

KONSTANTINOS

ZACHOS

and Remotesensing,includinggeophysical prospection, computer-aided as were discussedin the samepresentation usefultools to aid in analysis as such an undertaking, well as in the investigationof Nikopolis itself. methodwas in prospection, particular, citedas an important Geophysical ology by which at least somepartsof the city planof Nikopolismight be was beforeany excavation initiated.Symposiumparticipants established and interestedin the investigation preservawere deeply and organizers tion of the great city itself, and a coordinated, multifaceted, long-term effortwas formallydeclaredby the symposiumboardto be a desirable outcomeof the symposium.15 led Continuedconcernfor Nikopoliseventually to the appointment of MelinaMercouri, a special in 1986 by the GreekMinisterof Culture, Committee for the Preservationof Nikopolis, which was headed by of Evangelos Chrysos(nowbasedat the University Athens),who wasthen of Professor ByzantineHistoryat the Universityof Ioanninaand one of The committeemembersrepresented of the organizers the symposium. in Greecewith concernsor responsibilities the groupsand organizations for Nikopolis,includingthe GreekArchaeological Service,the Archaeoof the of Athens,the city of Preveza, University Ioannina, logicalSociety hiredby the committeeweregiven an officein the andothers.Architects and Town Hall of Preveza, they beganthe important jobs of mappingall and visible remainsin Nikopolis and its periphery, of documentingthe zone of Nikopolis. within the archaeological ownershipof all properties in The committeewas reconstituted occasionally the 1990s to reflectpolitical(bothlocalandnational)andinstitutional changes,but Chrysosreof the permutations the committee tainedthe chairmanship throughout until the completionof the NikopolisProject. in of Wisemanbegandiscussions With the encouragement Chrysos, 1988 with AngelikaDouzougli,the newly appointed (direcproistameni and of and tor)of the 12th Ephoreia Prehistoric Classical Antiquities, her in Konstantinos Zachos,seniorarchaeologist the sameephoreia, husband, in which collaboration a project the Nikopolisregion, on possible regarding lies within the purviewof that ephoreia. The 8th Ephoreiaof Byzantine also directed Frankiska by Antiquities, Kephallonitou, becameinvolvedin the earlyplanning,becauseLate Antique and Byzantineremainsin the of The decisameregionwere amongthe responsibilities that ephoreia. in both basedin loannina, sion was reached 1990 that the two ephoreias, of wouldjointlyshare responsibilities the project, the andBostonUniversity for when finalized, for a joint underwas so that the proposal the project, in The of taking,synergasia Greekterminology. directors the two ephoreias of with Wiseman,the Ameriand K. Zachoswerecodirectors the project of were canPrincipal and Investigator, otherrepresentatives the ephoreias first wasthen submitted to alsomembers the staff. of The project proposal the AmericanSchoolof ClassicalStudies,as then required Greeklaw by or for a projectinvolving Americansponsorship cosponsorship. basedon Therewas for a time consideration a collaborative of project that would carry with the group Nikopolisitself,workingin cooperation The out the regionalstudy,as envisionedat the Nikopolissymposium.16 at aimsof workat Nikopoliswouldhavebeen to determine least principal

15. Chrysos 1987, pp. 417-418. 16. Wiseman 1987.

THE NIKOPOLIS

PROJECT

17. van Andel and Runnels 1987; Jameson,Runnels,and van Andel 1994.

and the generaloutlineof the city plan throughgeophysical prospection froma tethered otherformsof remotesensing; photography blimpboth to of help in detectingthe townplanandto aidin the documentation aboveand intendedto providea stratigraphic groundremains; test excavations an controlfor regional ceramics, urgentneedbecausetherewerethen few These planswereabandoned in published groupsof well-datedceramics. as it becameclearthatthereweretoo manyconflicting competand 1991, rightsat Nikopolisitself for any one group, ing claimsto archaeological a Council especially new one, to obtainthe supportof the Archaeological for archaeological for approving in Athens, the responsible body permits of investigations any kind in Greece.The proposalas finallysubmitted wasfor a combinedarchaeological geologicalsurvey the region,but and of For not includingNikopolis,conductedin synergasia. 1991, the project of would involve mainlyground-truthing satelliteimageryand gaining with by greater familiarity the landscape the American staff,andfinalizing The the aims and methodologyof the regionalinvestigation. subsequent permitwas for threeyears,1992-1994, duringwhich the archaeological and geologicalinvestigations were carried There were studyseasons out. in the summers 1995 and 1996,when seniorstaff,basedin Ioanninato of were able to materialscollectedduringthe survey, study archaeological revisitthe surveyzone with staff reportsin hand and to discussproject and resultsandinterpretations. analyses studyboth of the artiLaboratory factsandthe archives havecontinuedsincethat time. A numberof scholars Greece,the United States,the United Kingin research contributed the eventual to dom, andothercountries design,inboth specificresearchaims and methodologiesadoptedby the cluding Nikopolis Project,especiallythose who have devoted so much of their time andeffortas members the staff.George(Rip) Rapp,a geoarchaeof at the University Minnesota,Duluth,with extensive of field expeologist riencein Greeceandotherpartsof the eastern was Mediterranean, one of the firstscholars and invitedto join the staff;he organized directed much of the project's and shorelinestudies. coringprogram, geologicalsurvey, at CurtisRunnels,an archaeologist BostonUniversity, broughthis expertisein the early of to prehistory Greeceandin survey the NikopolisProject. He wouldleadthe Palaeolithic of with the aid andcooperation his survey, Priscilla Fellowin Archaeology BostonUniverat Research wife, Murray, of Unisity,andTjeerdvanAndel, a geoarchaeologist formerly Stanford of then (andnow) of the University Cambridge. Runnelsandvan versity, Andel would now applysurveytechniques they hadjointlydevelopedon in Greeceto the investigation earlyhumansandhomiof projects southern nids in Epirus.17 Their survey, which supplemented, was conducted but carried by otherstaff,inout from,the intensivesurface separately survey volvedintensivegeomorphologic studiesin the detectionof Pleistocene whichtheythensearched. Bothwouldalsojoin in otherproject landscapes, of for in stone responsibilities-Runnels, example, the analysis prehistoric andvanAndel in geomorphology all periods,as well as providfor tools, concerns. ing counselandinsightfor allgeoarchaeological LucyWiseman of BostonUniversity's CenterforArchaeological Studieswas alsoa member of the stafffromthe beginning,servingboth as projectadministrator

JAMES

WISEMAN

AND

KONSTANTINOS

ZACHOS

and registrarof artifacts.Three advancedgraduate students in archaeology at Boston University were also part of the senior staff. Thomas Tartaron and Carol Stein were the primary team leaders in archaeological survey, and provided both supervision and guidance for others who subsequently became survey team leaders. Tartaron also developed a specific sampling strategy for the Acheron River valley and Ayios Thomas peninsula, reflecting the overall stratified sampling strategy of the project, and carried out a special study of the Bronze Age sites and materials, part of which was included in his doctoral dissertation.18Melissa Moore oversaw the study and registration of ceramics, and part of her research has been included in her Ph.D. dissertation.19Other staff and consultants included geologists, computer scientists, archaeologists, and specialists in various other fields; all staff and their affiliations during the Nikopolis Project are provided in Table 1.1. Students enrolled in a Boston University Archaeological Field School were invaluablemembersboth of the field surveyteams and the geological coring and survey units in 1992, 1993, and 1994. As a part of their archaeological training, they participated in all activities of the project in Greece, including the processing of artifacts,data processing on computer, digitizing of maps, ground-truthing of satellite imagery,topographical survey,geophysical prospection, aerial photography by tetheredblimp, and other investigations.Their names and the institutionswhere they were studying at the time are listed in Table 1.2.

SPECIFIC RESEARCH AIMS

Research aims, nested within the larger conceptual framework described above, relate mainly to specific time periods and include the following topics, phrased as questions, which much of the project's fieldwork was intended to answer. 1. What forms do the cultural remains of the earliest inhabitants of southern Epirus take, and how may we explain their distribution in the different periods of the Palaeolithic?What resources were exploited by the early humans and hominids, and what was the environmental setting? 2. What is the evidence for the shift from hunting/gathering groups to agriculturalsocieties? Can that shift be related to changes in the landscape? 3. What was the nature of the contacts between peoples of this region in later prehistoric times, especially in the Late Bronze Age, and groups on the shores of the Ionian Sea, in other parts of Greece, and more generally in the eastern Mediterranean? Do these contacts differ in quality during fully historical times? 4. How are colonial activities of southern Greeks manifested in this region? 5. What were the effects of the development of political leagues and interregional alliances on settlement patterns, sizes of sites, religious centers, and resource exploitation in Classical and Hellenistic times?

18. Tartaron1996. 19. Moore 2000.

THE

NIKOPOLIS

PROJECT

6. What were the effects of the historically documented Roman intrusion into Epirus (which was also the earliest intervention by Romans in Greek affairs) in the 3rd and 2nd centuries B.C., and how may they be identified in the landscape?How intrusive into local society were the Romans, and what activities (military,industrial, commercial, social, etc.) are indicated by the cultural remains? involved in the 7. What was the regional effect of the synoecism founding of Nikopolis by Octavian, later Augustus, first emperor of Rome? How are the new patterns of settlement and communication related to changes in the landscape itself? 8. What was the nature of the exploitation of the countryside in the Late Antique period (4th-6th centuries A.c.) and how was it related to the socioeconomic transformation into medieval times? More specifically,what was the economic basis of southern Epirus in late antiquity and in medieval times? When did the extensive exploitation of wetlands along the Ambracian Gulf begin, and when the deliberate reclamation of land from coastal lagoons?

METHODOLOGIES

The research design called for the archaeological sampling by intensive surface survey of all environmental zones: coastal plains, inland valleys, mountainous terrain,and upland valleys.The large size of the surveyzone precluded archaeological survey over the entire region. The selection of the areasto be surveyedwithin each environmental zone would be guided primarilyby acquiredknowledge of the region. Geological surveyand other geomorphologic investigationsprovidedimportantinformation,both negative and positive, influencing the selection of fields and transectsto survey; fieldwalking teams, for example, could avoid areas of recent alluviation where remains (if any) of prehistoric-medieval times would have been covered over and not detectable.The location of early historical or even Pleistocene landscapes exposed by erosion, on the other hand, offered opportunities for survey with greater expectation of detecting archaeological remains. Even so, occasional surveyswere conducted to test negative indications from geomorphology or satellite imagery,20 when fieldwalking as teams spent a day walking transects across the presumed relict coastlines of Ammoudia Bay that were formed by long-shore deposition in recent historical times. The negative results of the intensive survey confirmed the geomorphologic conclusions and the interpretations of imagery.The degree of visibility was recorded for all areas surveyed. Fields where vegetation was too dense for archaeological remains to be seen during preliminary reconnaissance were not selected for survey. This practice is an important consideration in evaluating the results of the survey,because in some other year, or some other time of year,those fields might be clear of vegetation, and might, of course, yield archaeological materials. On the other hand, in some instances fieldwalking teams were able to return to a region to survey fields that had been too densely covered for survey in a

20. A practicerecommendedin Sever andWiseman 1985, pp. 70-71.

IO

JAMES

WISEMAN

AND

KONSTANTINOS

ZACHOS

TABLE 1.1. PROJECT

Name

CODIRECTORS

STAFF AND THE YEARS OF THEIR

1991 1992

PARTICIPATION

1994 1995 1996

1993

Angelika Douzougli/KonstantinosZachos, 12th Ephoreiaof Prehistoricand ClassicalAntiquities Frankiska Kephallonitou,

8th Ephoreia of Byzantine Antiquities James Wiseman

ADMINISTRATION AND INVENTORY

0*

0 0 0

Lucy Wiseman (registrar of artifacts, administration) Melissa Moore (registrar of ceramics,archaeology) Lia Karimali (lithics, survey) Dimitra Papagianni, University of Cambridge (lithics, survey)

* 0

* *

* * * * * * e * * 0 *

KaterinaDakari,8th Ephoreiaof ByzantineAntiquities

(survey, Late Antique ceramics) Ricardo Elia (associatedirector,archaeology) Asymina Kardasi, Athens (Byzantine ceramics) * *

Stavroula Vrachionidou,12th Ephoreiaof Prehistoricand

Classical Antiquities (administration, survey) ARCHAEOLOGY, SENIOR STAFF * * *

*

Timothy Baugh (remotesensing, ground-truthing) Brenda Cullen (survey, remotesensing) Priscilla Murray (survey, drafting) Curtis Runnels (field director,Palaeolithic survey; lithics) Carol Stein (survey, remotesensing) Thomas Tartaron (survey, ground-truthing)

* * * *

* *

0

* *

* *

S

StavrosZabetas,Greek ArchaeologicalService (survey)

GEOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICS

Mark Besonen, Universityof Minnesota, Duluth

(geologicalsurvey, coring) Richard Dunn, University of Delaware (geologicalsurvey, coring)

ZhichunJing, Universityof Minnesota, Duluth

(geologicalsurvey, coring) Jon Jolly, Seattle, Washington (oceanography,instrumentation) * *

George (Rip) Rapp,Universityof Minnesota, Duluth

(geology,geoarchaeology) * *

0

Apostolos Sarris,Athens, Greece (geophysics)

Marie Schneider (geology,survey)

Tjeerdvan Andel, Universityof Cambridge

(Pleistocenegeology, geomorphology,geoarchaeology) * * *

Sytze van Heteren (geology) John Weymouth,Universityof Nebraska(geophysics) Li-Ping Zhou, Universityof Cambridge

dating) (geology, thermoluminescence

THE NIKOPOLIS

PROJECT

II

TABLE 1.1-Continued

Name

COMPUTER SCIENCE

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

Robert DeRoy (computerscience,remotesensing) Daniel Juliano (computerscience,remotesensing)

Rudi Perkins,Bangor,Maine (computer science)

PHOTOGRAPHY Michael Hamilton (aerial photography,generalphotography) Eleanor Emlen Myers' (aerialphotography) *

J. Wilson Myers (aerialphotography)

TOPOGRAPHICAL SURVEY AND DRAFTING

Theodoros Chazitheodoros,Greek ArchaeologicalService,

Athens (topographicalsurvey, drafting) David Clayton (topographicalsurvey, drafting) *

Athina Kotsani,Preveza(drafting)

Kostas Papavasileiou, Preveza (architecture,drafting)

a a

Anne Van Dyne, Seattle,Washington

(topographicalsurvey, drafting) GENERAL STAFF

0 a

Stephen Agnew (ground-truthing)

KaelAlford (survey)

Alesia Alphin (survey, inventory)

Betty Banks, Spokane,Washington (survey,inventory,

data entry) Mark Greco (survey) Cinder Griffin, Bryn Mawr (survey, inventory) *

a a

Nikola Hampe, Universityof Miinster (survey) Alan Kaiser(survey) PetraMatern, Universityof Miinster (survey)

Michele Miller (ground-truthing, survey) Lee Riccardi (survey, inventory) * S

0

*

KatrinVanderhuyde, Universityof loannina (survey) ElizabethWiseman, Littleton, Colorado

(photography,ground-truthing) CON SULTANTS

Wilson College (ceramics) VirginiaAnderson-Stojanovic,

Evangelos Chrysos, University of loannina (Byzantine history) * * *

*

* * *

HarrisonEiteljorgII, Bryn Mawr (databases, AutoCAD)

Panayiotis Paschos, IGME, Preveza (geology)

Staff memberslisted without an institutionalaffiliationor city were from Boston University.

I2

JAMES

WISEMAN

AND

KONSTANTINOS

ZACHOS

TABLE 1.2. FIELD SCHOOL

I992

STUDENTS

AND THEIR

HOME INSTITUTIONS

KaelAlford, Boston University AlexandraBienkowska,Boston University Anne Cockburn,Williams College Todd Gukelberger, SUNY, Albany Deborah King, RensselaerUniversity Dawna Marden,Universityof SouthernMaine Thomas Matthews, Utica College of SyracuseUniversity RichardRotman,Boston University Bayleh Shapiro,Boston University Jane Sontheimer,Boston University Anita Vyas,Boston University ErikaWashburn,Boston University 1993 AlessandroAbdo, Boston University Evie Ahtaridis,Universityof Pennsylvania TracyBarnes,Texas ChristianUniversity Arlyn Bruccoli,Bard College ChristinaCalvin, George Mason University Scott deBrestian,Boston University Antonina Delu, Universityof California,Riverside KatherineDemopoulos, Universityof California,Los Angeles Cheryl Eckhardt,Boston University JenniferFisher,Boston University Lorena Freeman,Universityof the South Stephani Kleiman,Loyola MarymountUniversity Noah Koff, Boston University

Natalie Loomis, TulaneUniversity Michael Marton, Franklinand MarshallCollege Martin McBrearty,FurmanUniversity Scott McCrimmon, Boston University Sean Mulligan, Boston University Wendy O'Brien,Boston University Dena Pappathanasi, Universityof New Hampshire Rudolph Perkins,Boston University Duke University Jamie Ravenscraft, JonathanWood, PrincetonUniversity KellyYounger,Loyola MarymountUniversity 1994 Lisa Davis, HarvardUniversity Mely Do, Universityof Pittsburgh Aviva Figler,Boston University Mike Gaddis, PrincetonUniversity Amy Graves,Miami University Leslie Harlacker, Boston University KarlaManternach,Loras College Joe Nigro, Boston University Anne Maxson, Duke University KathyMontgomery,Boston University JenniferMurray,SUNY, Buffalo VersalliusCollege, Brussels StephanPapageorgiou, T. J. Reed, Cornell University YasuhisaShimizu, Boston University Alison Spear,Mount Holyoke College

previous year.The methodology of the surface survey is discussed in detail by Tartaron in Chapter 2, but it is important to note here that surface surveys included both transects within large regions and intensive sampling, or complete coverage, of human-activity areas ranging from small single-activity sites to extensive settlements. In addition, one fortified town site (Kastri, in the lower Acheron valley) was selected for intensive urban survey. Geomorphologic studies formed part of the central core of the project, as required by the research concept. If we were to study the interaction between humans and their environment,we reasoned,one of the first steps must be to determine what that natural setting was-that is, what the landscape and other aspects of the environment were like over time. A number of investigations, therefore, were planned to provide the needed evidence. An extensive coring program was initiated in 1992 and continued through 1994 that was aimed at determining changes in shorelines over time both in the Ambracian Gulf and along the Ionian coast. The analyses of the cores, most of which were carriedout in the Archaeometry Laboratoryof the University of Minnesota, Duluth, also made it possible to establish a sequence of local change and, through radiocarbondating, to determine the chronology of change. Cores also provided microfauna,

THE

NIKOPOLIS

PROJECT

I3

21. See the discussionsin Wiseman 1992b, pp. 3-5; 1993a, pp. 12-13. 22. The following brief accountis intended mainly to explainwhat kinds of remote-sensingimagerywere acquiredand used by the project,and why they were used. 23. Wiseman 1996a, 1996b. 24. Stein and Cullen 1994; Wiseman 1996a, 1996b.

macrofauna,and pollen for paleoenvironmental reconstruction. Geomorphologic investigations involved geological survey in all parts of the survey zone, and intensive work, including coring and mapping, at selected sites or regions. Geological survey and coring were coordinated as closely as possible with the archaeological survey, so that field teams often comprised both geologists and archaeologistsworking together. We had planned offshore investigations to supplement the study of shoreline change, and there was a promising beginning to that research. The Hellenic Navy dispatched a research ship, the Pytheas,to work with project staff for two weeks in 1992. A Klein side-scan sonar and a Klein subbottom profilerwere towed behind the ship both in the Ionian Sea and in the Ambracian Gulf, the former recording features on the surfaceof the sea bottom, the latter detailing the depth and nature of sediments below the sea floor.The survey,in perpendiculartransects forming a grid pattern, produced data covering some 300 linear kilometers, which to this date have received only preliminary analysis21 because they were subsequently another bureau of the Greek government. sequestered by Remote sensing from space was determined to be a potentially useful tool for our surveywell before the initiation of the project,as noted above.22 We did not, however, expect remote-sensing imagery to play a significant role in the detection of archaeological sites because at that time most remote sensors were known to be unsuccessful in penetrating dense vegetation, which covered much of our survey zone.23What is more, although the resolution of satellite imagery had been improved, the smallest picture element (= pixel) of available multispectral imagery was 20 meters to a side, too large to be helpful in detecting the small features and artifacts of most archaeologicallandscapes. It is an interesting sidelight on the development of archaeological methodologies that remote sensing in the end proved to be quite useful in detecting Pleistocene landscapes,which could then be located and searchedby ground-truthing survey teams, and which resulted in the discovery of five prehistoric sites.24Its greatest value, we thought at the time, would probablylie in its ability to provide imagery of the entire region that would permit the classification and identification of present-day land cover. It could, therefore, help in defining the environmental zones of the survey area;show currentconditions that might affect the conduct of surfacesurvey;and perhapsprovide some insight into routes of communication among known (or subsequently discovered) ancient settlements. The imagery would also serve as a layer in the computeraided GIS (geographic information system) maps to be generated by the project, and we hoped to develop spectral signatures-that is, a characteristic spectralresponse identifiable in the imagery-for features of archaeological interest. Both multispectral (MSS) and panchromatic imagery of the entire surveyzone was acquiredfrom the French satellite company SPOT before the beginning of fieldwork in 1991. SPOT imagery was selected primarily because its spatial resolution was the finest availablefor general researchat that time: MSS at 20 meters, panchromatic at an even finer 10 meters. The United States'Thematic Mapper (TM) satellite imagery,in contrast, has a resolution of 30 meters. Since spatial resolution on the ground is a

I4

JAMES

WISEMAN

AND

KONSTANTINOS

ZACHOS

Figure 1.3. Multispectral image (SPOT) of the northern part of the survey zone

Figure 1.4. Multispectral image (SPOT) of the southern part of the survey zone. Leucas (lower left) and other regions south of the Ambracian Gulf lie outside the survey area.

THE

NIKOPOLIS

PROJECT

I5

function of altitude as well as the type of sensor, we could have achieved finer resolution from sensors mounted on aircraft, instead of spacecraft. The only airborne platform available to the project, however, was a tethered blimp, which, although excellent for individual sites and smaller areas, was not appropriatefor such a large regional survey as ours because of the time and other logistical difficulties such coverage would require.Full coverage of the survey zone required two images, both in MSS and panchromatic. The northern image (Fig. 1.3) included almost the entire survey zone, and the second (Fig. 1.4) added the southernpart of the Nikopolis peninsula, along with areas outside the survey zone: Actium, Leucas, and other areas south of the Ambracian Gulf. Multispectral imagery is particularlyuseful in showing different types of landcover because landcover types have a different reflectance value in each band of the electromagnetic spectrum. The combination of these numeric values in the bands used by the sensor (SPOT uses green, red, and near infrared) constitutes a spectral signature, which may be represented by a (false) color assigned in a multispectralimage generated by the computer.This assigning of colors, or classification of images, is a process whereby each land area having the same kind of cover receives the same (false) color in the image. The researcher,then, after identifying on the ground at least once the class representedby a particularcolor as a particular landcover (e.g., class 12 = red = limestone outcropping), may reasonably expect other patches of red in that image to represent the same kind of landcover;in the example just cited, more limestone outcrops. In practice, however,the classification of an image may result in the combining of several signatures into a single class, or the subdivision of a signature into more than one class, depending on the number of classes the researcher chooses for the image and on other physical aspects of the landcover.Making use of the facilities of the Center for Remote Sensing at Boston University, Carol Stein classified the MSS imagery of the Nikopolis Project into fifty classes,with all unclassifiedlandcoverassignedclass 0. The number of classes was considerably larger than proved useful in the field because the fine distinctions the classification made possible resulted in the identification of many kinds of landcover that were irrelevantfor our research. For example, there was no reason for us to be able to distinguish kiwi plants from maize, which our classification enabled us to do. In retrospect, we now see that fewer landcover classes (say,fifteen to twenty) would have been preferable,because such a classificationwould have resulted in a beneficial lumping together of rock outcroppings, and would have created other continuous zones-as in fact they were-of barrenland, instead of a number of separate units in the classified imagery.The finer distinctions involved in developing a spectral signature of an archaeologicalfeature, or archaeological feature combined with a particularvegetation, would still have been theoretically possible. The relevant portions of the MSS images were then subdivided by Stein into twenty scenes, each representing about 100 km2on the ground, and printed for field use. Transparentoverlays at the same size were also printed, five for each scene, each displaying ten of the fifty false colors of classes of landcover,so that field teams were able to use them conveniently

I6

JAMES

WISEMAN

AND

KONSTANTINOS

ZACHOS

Z ~ ~. W

of Figure1.5.The erodedlandscape ~ .......Kokkinopilos abovethe Louros . _ ~~~~~ ~ __ ............ .River gorge

to determine what on the ground was actually being represented by each false color; this kind of fieldwork is called "ground-truthing."The hard copy of the scenes and transparencieswere at a scale of 1:50,000, so they could be used in conjunction with our topographical maps of the same scale; the transparenciescould be used as overlays of the maps, just as they were on the printed scenes. Ground-truthing, a focus of our fieldwork in 1991, required precise location of the observed landscape, so the field teams were also provided with copies of the panchromatic scenes, and even more detailed subscenes. Locations were marked on 1:5,000 topographical maps, and aerialphotographs (scale: 1:20,000) also were used to help locate specific features in the landscape; both maps and photographs were obtained from the Geographic Service of the Hellenic Army. Additional locational information was obtained by 1) global positioning systems (GPS), which provideUTM as well as longitude/latitude readings through communication with the navigational satellites (21 in number in 1991) that constantly orbit earth; 2) altimeter readings (more accurate at that time than GPS in determining altitude), when benchmarks are not readily available;and 3) readings by electronic laser theodolite, for still more precise location in three dimensions, as appropriate.These ground-truthing expeditions, which were led by Timothy G. Baugh during the first, preparatoryfield season, resulted in the identification of 27 of the 50 classes of landcover.An additional 12 classes were created for areaswith distinctive features related to human activity whose spectral signatures might serve as guides to the location of other similar areas:e.g., quarries or ancient sites. One of those new classifications was the eroded Pleistocene landscape of Kokkinopilos (Fig. 1.5), which eventually led to the discovery of five other similar landscapes, and prehistoric sites, as mentioned above. The experience gained in using GPS, satellite imagery,and topographic maps in 1991 was invaluable in developing standardproceduresfor the surveyteams of 1992-1994.

THE

NIKOPOLIS

PROJECT

I7

25. Hemans, Myers, and Wiseman 1987. 26. Hemans, Myers, and Wiseman 1987.

of What is more,the ground-truthing several expeditions 1991 provided with the Epirotelandmembers the staffwith a fundamental of familiarity scape. Anotherkind of remotesensing,aerialphotography from a tethered wasemployed the project documentsomeof the larger to known by blimp, ancientsites.Foursiteswerephotographed radio-controlled with cameras in 1992 by field teamsled byJ.Wilson MyersandEleanorEmlenMyers: the fortified townof Kastro Rogonsouthof the LourosRiver gorge;Kastro a fortifiedtown in an enclosedplain northof KastroRogon; Rizovouni, the Romanaqueduct nearAyios Georgiosin the LourosRivergorge;and VoulistaPanayia, Hellenisticsite overlooking narrows the same a the of further northat Kleisoura. MichaelHamilton,who wasthe project's gorge staffphotographer, the blimp-photography led teamin 1993 that photothe and graphed largefortifiedClassical Hellenisticsite at the abandoned modernvillageof Palaiorophoros, northof the townof Louros. The use of this techniquewas limitedby a numberof factors. The necessityfor permits frommultiplecivilianand military authorities resulted numerous, in of anddisruption schedules in costlydelays (e.g.,blimpphotography 1991 had to be cancelledand the 1993 seasonwas severely The excurtailed). and increased 1993whenwe decided, in pensewas significant, wasgreatly for safetyreasons, use heliumin the blimpinsteadof less expensive, to but flammable In addition, therewerethe normaldelaysand highly hydrogen. logisticalproblemsimposedby the techniqueitself, such as the need to awaitfavorable winds (thatis, none or verylight) andotherclimaticconditions.The photographic resultsof this technique,however,are highly are useful,especially when, as on the NikopolisProject, multiplecameras usedto provide both in blackandwhite andin color.A particular coverage of froma tethered advantage photography blimpis thatthe viewsarevertical and so can be used in mapping,unlikethe obliqueviews frequently It gatheredby camerason aircraft. is also possiblein a single flight to obtainphotosat a seriesof elevations to a maximum 800 m, thereby of up both close-upsand extensivecoverage Fig. 1.6).The aerial (see providing also can be scannedand then combinedwith the multispecphotograph tralimage of that area,a techniquewe used in the studyof the fortified town site of Palaiorophoros. The BostonUniversity blimp-photography systemwas designedbyJ. Wilson Myers,who modeledit on the systemhe had developedearlier, and is described detailelsewhere.25 multispectral in A video camera, sucusedon a tethered cessfully blimpin the Corinthia a BostonUniversity by teamin 1986,26 not usedby the NikopolisProject, couldusefully was but be deployed the future, in sinceit canprovide in high spatialresolution six bandsof the electromagnetic spectrum. of kindswas carried at a number out Geophysical prospection various of sites,primarily providedataon possiblesubsurface to in features areas where surfacesurveysuggestedsignificanthumanactivity. Only limited waspossiblein 1992 becauseof staffingandequipment prospection probwere conductedin 1993 lems, but successfulprogramsof investigation underthe direction JohnWeymouthof the University Nebraska of of and

I8

JAMES

WISEMAN

AND

KONSTANTINOS

ZACHOS

Figure1.6. Aerialview of the fortifiedtown site at KastroRogon

from an elevation of 400 m. Photoby

J. Wilson and Eleanor Emlen Myers

in 1994, when Weymouth was succeeded by his protege, Apostolos Sarris. Instrumentation included a proton magnetometer, electrical resistivity meter, and electromagnetic conductivity meter, of which the first was most frequently used. Weymouth and Sarris are preparing a report on their investigations for volume 2 of this series, and the results are also being incorporated into reports on the town sites where geophysical prospection detected significant subsurfacefeatures such as probable kilns and buildings. The permit of the Nikopolis Project was for survey, not excavation; indeed, under Greek law a single permit might cover only one or the other. As a result, the project had an arrangementwhereby one of the cooperating Greek ephoreias would perform excavation if a site was discovered by the project to be in need of emergency attention. The discovery at the Roman villa site of Strongyli, for example, that burialshad been plundered by clandestine diggers and parts of floor mosaics had been exposed A prompted excavations by the Greek ephoreia to ensure conservation.27 similar situation arose at Frangoklisia, probably another Roman villa, on the Ionian coast near Loutsa.28The project did carry out limited excavation in 1991 at the request of the Prehistoric and Classical Ephoreia in the Roman aqueduct below the village of Ayios Georgios, so that details of the water channels and the chronological sequence of aqueduct bridges across the Louros River might be studied and drawn (Fig. 1.7). Our work here resultedin, among other conclusions, the confirmation that the northern bridge was built and utilized for the aqueduct after the earlier,Augustan bridge had been damaged and abandoned.

27. Douzougli 1998a, 1998b. 28. Zachos 1998.

THE

NIKOPOLIS

PROJECT

I9

Figure1.7. Aerialview of the water channel(right)andaqueduct bridges acrossthe LourosRiverfroman elevationof 320 m. Photo by

J. Wilson and Eleanor Emlen Myers

i .

'

s

t

a f

DOCUMENTATION

All team leadersand individual investigators kept a dailyrecordof their activities observations bound,hardback and in which alsoconnotebooks, tainedphotographic printsanddrawings, wereindexeduponcompleand tion.The notebooks werenumbered This historisequentially. permanent cal record,partiallyin narrative form,was supplemented an arrayof by printedformsthatwerefilledout in the fieldor laboratory, appropriate, as providingdetailedinformation all aspectsof the investigations, on from surface surveyto artifact These two kindsof writtendocumeninventory. tationwerecross-referenced a dailybasis,but it wasprimarily series on the of printedformsthat providedthe bulk of the information that was enteredinto the computer I databases. summarize belowthe principal databasesof the NikopolisProject. formswere numbered yearand seAll by with an quentialaccessionwithin the year,e.g., 92-1. Databasesmarked asterisk dealtwith in greater are detailin Chapter2. 1. Ground-Truthing Form(GTF). A GTF was filledout at every locationwhereground-truthing conductedto identifythe was landcover classesin the satelliteimagery. of *2.Tract(T). The tract,an areaof arbitrary is the project's size, or primary surveyunit whetherin the countryside within a large site.The database includeslocation,size, description, conditions of the survey, total artifact results. counts,and summary

20

JAMES

WISEMAN

AND

KONSTANTINOS

ZACHOS

*3. Site/Scatter(SS). An SS is anylocationwheretherewas a or of concentration artifacts that is marked visible,in situ by This categoryincludesanylocationfroma small remains. includes scatterof lithicsto a fortifiedtown.The database and location,size, description, chronology, surveydata. *4.Walkover (W). A W indicatesa nonintensive surveyor a visit or eitherfor reconnaissance reexamination. includesthe description, The sampledatabase 5. Sample. counts, collectedduring material dates,and otherdetailsof all cultural of are survey. Samplenumbers identicalto the numbers the surveyunitswheretheywerecollected. and werecatalogued Artifactsselectedfor inventory 6. Inventory. into Selectioncriteria storedaccording material/function. for cluded,amongothers,significance datingor functional as or analysis, the likelihoodof publication a type artifact. a recordof the context This database 7. SpecialAnalyses. provides fromclay and natureof samplestakenfor laboratory analyses, samplesto geologicalcores. A and 8. Photo Inventory. recordof all black-and-white color

photographs taken by the Nikopolis Project, in the field, photo studio, or laboratory. 9. Drawing Inventory.A record of all drawings made by and for the

project.

Relational databases 1-6 were all created in FoxBase+ for Mac, which seemed to the staff, including the computer scientists and engineers, the most suitable at the time. Unfortunately,when the softwarewas redesigned as FoxPro in 1993, databases in earlierversions of the software could not be upgraded;all windows for data entry would have had to be redesigned and the data reenteredto use FoxPro,a duplication of effort we declined to do. The program, therefore, lacks some of the flexibility and ease of some of the more recent databases, but still has served the project well. The design of the relational databases reflects the archaeological concerns and experience of the senior staff, and there was much (both fruitful and lively) discussion between the archaeologists and the computer experts who put it all together. The various forms and notebooks were supplemented by copies of maps, primarily the 1:5,000 topographical maps, on which field teams marked surveylocations and other observations. Each member of the staff also prepareda staff report at the end of each season, which summarized the activities each person performed, the forms and notebooks in which the records were kept, and whatever other comments the staff desired to make.There were numerous other logistical records,including logs to keep track of the forms assigned for field use, and extensive cross-referencing. We hold redundancy in archaeological records to be a virtue because it makes it possible to discover the inevitable recording errorsthat occasionally creep into databases, however carefully they are kept. All databases and other archives of the Nikopolis Project are stored in the Center for Archaeological Studies at Boston University.

THE

NIKOPOLIS

PROJECT

2I

POST-FIELDWORK ANALYSES

During study seasonsin 1995 and 1996, materialscollectedduringthe and werereexamined studied Ioannina. Byzantine in The surveys Ephoreia former madeavailable studyspace secularized for the mosque, FetiyeDzami, of locatedon the highestpartof the fortress Ali Pashaandadjacent the to new Museumof Byzantineand Post-Byzantine The Archaeology. glorious view fromone side of the mosqueincludedthe lake of Ioanninaand the PindosMountains,andthereweretreesnearby that offeredshadefor staff memberswho might be workingoutside.The staff is particularly for sucha splendidplaceto gratefulto the ByzantineEphoreia providing and ClassicalEphoreiafor permittingthe study,and to the Prehistoric acrosstown from the Archaeological surveymaterialto be transported Museumto the Kastroduringtwo summers. During each of the two studyseasons,the seniorstaff also had the to areas teams precious opportunity revisit survey unaccompanied survey by to direct,and not burdened with surveysto conductor detailedformsto fill out. The staff,then, were ableto contemplate the spot the obseron vations of previousyears, and had the leisure to discuss observations andinterpretations eachotherin the midstof the landscape were with we studying.

PRESENTATION OF RESULTS

Preliminary reports of the Nikopolis Project appeared regularlyin Greek in the Archaiologikon Deltion29and in English in Contextand the Nikopolis Newsletter,publications of Boston University's Center for Archaeological Studies.30Papers by several members of the staff have appearedin full or in abstract form in the published transactions of the several conferences and symposia at which they were presented,31and a few special reports have been published in journals and edited volumes of essays.32 addiIn tion to the doctoral dissertationsof Moore and Tartaron,which were based mainly on project results and have been cited above, a dissertation by Dimitra Papagianni also includes researchon material from the Nikopolis Project.33Chapter 5 in this volume, written by Mark Besonen, George (Rip) Rapp, and ZhichunJing, is based in part on Besonen's M.S. thesis.34 The present book is the first of two volumes of final reports. Chapter 1, by Wiseman and Zachos, provides a history of the Nikopolis Project, and discussions of the research aims, the interdisciplinary methodologies employed, the databases,and the organization of staff and responsibilities. In the second chapterTartaronpresents in detail the methodology of the diachronic surface survey and places both the methodology and the aims within the historical and theoretical context of survey archaeology,especially as that field has evolved in the archaeology of Europe. These two chapters,which constitute an introduction to the work of the project, provide a historical, theoretical, and methodological frameworkwithin which the results of the overall interdisciplinaryproject may be understood and evaluated. They are not intended to be summaries of the results them-

29. Wiseman, and Zachos,

Kephallonitou1996, 1997, 1998. 30. Wiseman 1991,1992a, 1992b, 1993a, 1993b, 1994, 1995a, 1995b, 1997a. 31. Rapp andJing 1994; Runnels 1994; Stein and Cullen 1994;Tartaron 1994;Tartaronand Zachos 1999; Wiseman 1997a, 1997b;Wiseman and Douzougli-Zachos 1994;Wiseman, Robinson, and Stein 1999; reportsby severalstaff membersrecentlyappeared in Isager2001. Articles and abstractsin presshave been omitted here. 32. Runnels and van Andel 1993b; Tartaronand Runnels 1992;Tartaron, Runnels, and Karimali1999. 33. Papagianni2000, which is based on her (1999) dissertationat the Universityof Cambridge. 34. Besonen 1997.

22

JAMES

WISEMAN

AND

KONSTANTINOS

ZACHOS

selves, which arepresented in the reports that follow in this volume and its forthcoming companion volume. In Chapter 3 Runnels and van Andel present the results of the Palaeolithic survey,which they conducted as a supplement to the diachronic survey. Their methodology, developed over some fifteen years of survey in southern and central Greece, was based first on the investigation of the paleoenvironment, especially the geological history of Pleistocene sediments and other landforms.Their report thus deals comprehensivelywith the geomorphology and changes in the environment of southern Epirus in early prehistoric times, as well as the cultural evolution of its human inhabitants, from the Lower Palaeolithic to the Mesolithic. One of the of most remarkable the open-air Palaeolithicsites investigatedby the project is Spilaion, an Early Upper Palaeolithic site near the currentmouth of the Acheron River, where the ground surface was littered with an estimated 150,000 lithic artifacts. Runnels, Evangelia Karimali, and Brenda Cullen report in Chapter 4 on their study of the Spilaion assemblage, including the results of a spatial analysis of the distribution of the artifacts. Chapters 5 and 6 carrythe discussion of the geomorphology of southern Epirus and its relationships to archaeologicalsites from the end of the Pleistocene to the present. Both reports are based on extensive geologic coring programs and intensive laboratory analyses of the cores, as well as other geomorphologic investigations in the field. ZhichunJing and George (Rip) Rapp document the changes over the past 10,000 years in the coastal landscape of the Nikopolis peninsula and the area to its east, which comprises most of the north coast of the Ambracian Gulf. The locations of the important Classical, Roman, and medieval town sites in this region, and of human habitation generally, are related to the dramatic changes in the landscape,which are themselves shown to result from a variety of environmental, geomorphologic, and cultural factors. Besonen, Rapp, and Jing report in detail on the post-Pleistocene geologic history of the lower Acheron valley,tracing the changing course of the Acheron River,the creation and demise of the Acherousian lake, and the gradual change over time of the deep embayment known to Strabo as the Glykys Limen, where large fleets of ships found anchorage both in Greek and Roman times, to the small bay of the present day at the mouth of the Acheron River.The historical implications of the coastal changes are also discussed. In a final chapter the editors comment briefly on the results reportedin this volume. Volume 2 of Landscape in will inArchaeology SouthernEpirus, Greece clude a catalogue of sites/scatters and all tracts surveyed; reports on the pottery,lithics, and other artifacts;and a chronological presentation of the cultural remains in their environmental contexts.

También podría gustarte

- On the Origin of Continents and Oceans: Book 2: The Earths Rock RecordDe EverandOn the Origin of Continents and Oceans: Book 2: The Earths Rock RecordAún no hay calificaciones

- Early Mesoamerican Social Transformations: Archaic and Formative Lifeways in the Soconusco RegionDe EverandEarly Mesoamerican Social Transformations: Archaic and Formative Lifeways in the Soconusco RegionAún no hay calificaciones

- Geology: A Fully Illustrated, Authoritative and Easy-to-Use GuideDe EverandGeology: A Fully Illustrated, Authoritative and Easy-to-Use GuideCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (10)

- Colonisation, Migration, and Marginal Areas: A Zooarchaeological ApproachDe EverandColonisation, Migration, and Marginal Areas: A Zooarchaeological ApproachAún no hay calificaciones

- Time and Complexity in Historical Ecology: Studies in the Neotropical LowlandsDe EverandTime and Complexity in Historical Ecology: Studies in the Neotropical LowlandsCalificación: 1 de 5 estrellas1/5 (1)

- Why Geology Matters: Decoding the Past, Anticipating the FutureDe EverandWhy Geology Matters: Decoding the Past, Anticipating the FutureCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (4)

- Greek Colonization in Local Contexts: Case studies in colonial interactionsDe EverandGreek Colonization in Local Contexts: Case studies in colonial interactionsJason LucasAún no hay calificaciones

- The Archaeology of Aquatic Adaptations: Paradigms For A New MillenniumDocumento64 páginasThe Archaeology of Aquatic Adaptations: Paradigms For A New MillenniumvzayaAún no hay calificaciones

- Summary Of "The Origin Of Humankind" By Richard Leakey: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESDe EverandSummary Of "The Origin Of Humankind" By Richard Leakey: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESAún no hay calificaciones

- Geopedia: A Brief Compendium of Geologic CuriositiesDe EverandGeopedia: A Brief Compendium of Geologic CuriositiesAún no hay calificaciones

- Escaping the Labyrinth: The Cretan Neolithic in ContextDe EverandEscaping the Labyrinth: The Cretan Neolithic in ContextAún no hay calificaciones

- Current Approaches to Tells in the Prehistoric Old World: A cross-cultural comparison from Early Neolithic to the Iron AgeDe EverandCurrent Approaches to Tells in the Prehistoric Old World: A cross-cultural comparison from Early Neolithic to the Iron AgeAntonio Blanco-GonzálezAún no hay calificaciones

- Syesis: Vol. 3, Supplement 1: The Archaeology of the Lochnore-Nesikep Locality, British ColumbiaDe EverandSyesis: Vol. 3, Supplement 1: The Archaeology of the Lochnore-Nesikep Locality, British ColumbiaAún no hay calificaciones

- Novel Science: Fiction and the Invention of Nineteenth-Century GeologyDe EverandNovel Science: Fiction and the Invention of Nineteenth-Century GeologyAún no hay calificaciones

- Ancient Architecture of the SouthwestDe EverandAncient Architecture of the SouthwestCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- The Generation of Life: Imagery, Ritual and Experiences in Deep CavesDe EverandThe Generation of Life: Imagery, Ritual and Experiences in Deep CavesAún no hay calificaciones

- The Oasis Papers 2: Proceedings of the Second International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis ProjectDe EverandThe Oasis Papers 2: Proceedings of the Second International Conference of the Dakhleh Oasis ProjectAún no hay calificaciones

- First Peoples of Great Salt Lake: A Cultural Landscape from Nevada to WyomingDe EverandFirst Peoples of Great Salt Lake: A Cultural Landscape from Nevada to WyomingAún no hay calificaciones

- Holes in Our Moccasins, Holes in Our Stories: Apachean Origins and the Promontory, Franktown, and Dismal River Archaeological RecordsDe EverandHoles in Our Moccasins, Holes in Our Stories: Apachean Origins and the Promontory, Franktown, and Dismal River Archaeological RecordsJohn W. IvesAún no hay calificaciones

- Syesis: Vol. 4, Supplement 1: Archaeology of the Gulf of Georgia area--a Natural Region and Its Culture TypesDe EverandSyesis: Vol. 4, Supplement 1: Archaeology of the Gulf of Georgia area--a Natural Region and Its Culture TypesAún no hay calificaciones

- Diversity in Open-Air Site Structure across the Pleistocene/Holocene BoundaryDe EverandDiversity in Open-Air Site Structure across the Pleistocene/Holocene BoundaryKristen A. CarlsonAún no hay calificaciones

- New Directions in Cypriot ArchaeologyDe EverandNew Directions in Cypriot ArchaeologyCatherine KearnsAún no hay calificaciones

- A Late Pleistocene Site On Oregons SouthDocumento4 páginasA Late Pleistocene Site On Oregons SouthAshok PavelAún no hay calificaciones

- The Connected Iron Age: Interregional Networks in the Eastern Mediterranean, 900-600 BCEDe EverandThe Connected Iron Age: Interregional Networks in the Eastern Mediterranean, 900-600 BCEAún no hay calificaciones

- Prehistory of PolynesiaDocumento37 páginasPrehistory of PolynesiaKaren RochaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Nile: Natural and Cultural Landscape in EgyptDe EverandThe Nile: Natural and Cultural Landscape in EgyptHarco WillemsCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1)

- Stonehenge and Other British Stone Monuments Astronomically ConsideredDe EverandStonehenge and Other British Stone Monuments Astronomically ConsideredAún no hay calificaciones

- A New Golden Age of Archeology: Recent Discoveries in ArmeniaDe EverandA New Golden Age of Archeology: Recent Discoveries in ArmeniaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Ancient Life History of the Earth A Comprehensive Outline of the Principles and Leading Facts of Palæontological ScienceDe EverandThe Ancient Life History of the Earth A Comprehensive Outline of the Principles and Leading Facts of Palæontological ScienceAún no hay calificaciones

- A Natural History of the New World: The Ecology and Evolution of Plants in the AmericasDe EverandA Natural History of the New World: The Ecology and Evolution of Plants in the AmericasAún no hay calificaciones

- Mammoths, Sabertooths, and Hominids: 65 Million Years of Mammalian Evolution in EuropeDe EverandMammoths, Sabertooths, and Hominids: 65 Million Years of Mammalian Evolution in EuropeAún no hay calificaciones

- Molluscs in Archaeology: Methods, Approaches and ApplicationsDe EverandMolluscs in Archaeology: Methods, Approaches and ApplicationsAún no hay calificaciones

- A Short History of Planet Earth: Mountains, Mammals, Fire, and IceDe EverandA Short History of Planet Earth: Mountains, Mammals, Fire, and IceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (10)

- Desert Migrations People Environment andDocumento42 páginasDesert Migrations People Environment andCristianAún no hay calificaciones

- On the Road of the Winds: An Archaeological History of the Pacific Islands before European Contact, Revised and Expanded EditionDe EverandOn the Road of the Winds: An Archaeological History of the Pacific Islands before European Contact, Revised and Expanded EditionCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (2)

- Archaeology and Ethnography in MesseniaDocumento10 páginasArchaeology and Ethnography in MesseniaΕλένη ΓαϊτάνηAún no hay calificaciones

- Recent Developments in Southeastern Archaeology: From Colonization to ComplexityDe EverandRecent Developments in Southeastern Archaeology: From Colonization to ComplexityCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (2)

- Gómez Jimenez Et Al - Erosion AmbientalDocumento13 páginasGómez Jimenez Et Al - Erosion AmbientalSeba1905Aún no hay calificaciones

- 11 Hyman - Technology TransferDocumento30 páginas11 Hyman - Technology TransferJean Paul Orellana MoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- PaleontologyDocumento51 páginasPaleontologyDharani RajAún no hay calificaciones

- An Archaeology of Prehistoric Bodies and Embodied Identities in the Eastern MediterraneanDe EverandAn Archaeology of Prehistoric Bodies and Embodied Identities in the Eastern MediterraneanMaria MinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Elefanti, Panagopoulou, Karkanas - The Evidence From The Lakonis Cave, GreeceDocumento11 páginasElefanti, Panagopoulou, Karkanas - The Evidence From The Lakonis Cave, GreecebladeletAún no hay calificaciones

- The Handy Geology Answer BookDocumento458 páginasThe Handy Geology Answer Booksuemahony100% (1)

- Evolution and Escalation: An Ecological History of LifeDe EverandEvolution and Escalation: An Ecological History of LifeAún no hay calificaciones

- Fathoming the Ocean: The Discovery and Exploration of the Deep SeaDe EverandFathoming the Ocean: The Discovery and Exploration of the Deep SeaCalificación: 2.5 de 5 estrellas2.5/5 (4)

- V. Boroneant - The Mesolithic Habitation Complexes in The Balkans and Danube BasinDocumento15 páginasV. Boroneant - The Mesolithic Habitation Complexes in The Balkans and Danube Basinkamikaza12100% (1)

- Exotica in the Prehistoric MediterraneanDe EverandExotica in the Prehistoric MediterraneanAndrea VianelloAún no hay calificaciones

- Forces of Transformation: The End of the Bronze Age in the MediterraneanDe EverandForces of Transformation: The End of the Bronze Age in the MediterraneanChristoph BachhuberAún no hay calificaciones

- 2010 Cnty Shooting Areas FinalDocumento1 página2010 Cnty Shooting Areas FinalAllison StuartAún no hay calificaciones

- Jheri, Paikhed, Chasmandva Chikkar, Mohankavchali Dabdar & KelwanDocumento20 páginasJheri, Paikhed, Chasmandva Chikkar, Mohankavchali Dabdar & KelwanvmpandeyAún no hay calificaciones

- Site Visit ReportDocumento27 páginasSite Visit ReportuntoniAún no hay calificaciones

- Buena Mano Q1 2012 Metro Manila Catalog1Documento48 páginasBuena Mano Q1 2012 Metro Manila Catalog1Marlene YmasaAún no hay calificaciones

- Bhutan National Urbanization Strategy 2008Documento155 páginasBhutan National Urbanization Strategy 2008Sonam Dorji100% (1)

- Heavenly Hills of Mystical Munnar - Kerala TourismDocumento5 páginasHeavenly Hills of Mystical Munnar - Kerala TourismKUMAAR HOLIDAYSAún no hay calificaciones

- Locating Places On Earth - 113228Documento71 páginasLocating Places On Earth - 113228VILLACORTA, Jhoycerie FernandoAún no hay calificaciones

- Ajuan Sign Board MFPDocumento2 páginasAjuan Sign Board MFPCintya NursyifaAún no hay calificaciones

- Intro To Geospatial Data and Maps in RDocumento13 páginasIntro To Geospatial Data and Maps in RQi Nam WowwhstanAún no hay calificaciones

- F - 5540 ASWR Floodplain Zoning Simulation by Using HEC RAS and CCHE2D Models in The - PDF - 7393 PDFDocumento8 páginasF - 5540 ASWR Floodplain Zoning Simulation by Using HEC RAS and CCHE2D Models in The - PDF - 7393 PDFचन्द्र प्रकाशAún no hay calificaciones

- The Seven Great Monarchies: BY George Rawlinson, M.A.Documento126 páginasThe Seven Great Monarchies: BY George Rawlinson, M.A.Gutenberg.org100% (2)

- The Philippine: Disaster Risk Reduction and ManagementDocumento35 páginasThe Philippine: Disaster Risk Reduction and ManagementChristine Rodriguez-GuerreroAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Study 1 Philippines China and Scarborough ShoalDocumento3 páginasCase Study 1 Philippines China and Scarborough ShoalaadlabbaoAún no hay calificaciones

- Module 6B Maps and MappingDocumento9 páginasModule 6B Maps and MappingCRox's BryAún no hay calificaciones

- Rajasthan Public Service Commission, AjmerDocumento3 páginasRajasthan Public Service Commission, Ajmergpc dausaAún no hay calificaciones

- SeaDarQ Brochure WebDocumento4 páginasSeaDarQ Brochure WebWesley JangAún no hay calificaciones

- Proposed 2 Storey Residential Building With Roof Deck: Lot 26 BLK 28 South Springs Binan, LagunaDocumento1 páginaProposed 2 Storey Residential Building With Roof Deck: Lot 26 BLK 28 South Springs Binan, LagunaKiesha SantosAún no hay calificaciones

- F.Gualla - NGEM01 (Elevation Angle) PDFDocumento84 páginasF.Gualla - NGEM01 (Elevation Angle) PDFhakimAún no hay calificaciones

- Masica - 02 - The Modern Indo-Aryan Languages and DialectsDocumento22 páginasMasica - 02 - The Modern Indo-Aryan Languages and Dialectspkirály_11Aún no hay calificaciones

- DGPS Survey of Boundaries in State Forest DepartmentsDocumento16 páginasDGPS Survey of Boundaries in State Forest DepartmentsLakhwinder SinghAún no hay calificaciones

- PPTDocumento20 páginasPPTGeny Atienza0% (1)

- Waterfront TerminologyDocumento19 páginasWaterfront TerminologyOceanengAún no hay calificaciones

- Airport Information: Details For KENNEDY INTLDocumento55 páginasAirport Information: Details For KENNEDY INTLEO LozadiAún no hay calificaciones

- M.Ed. Thesis 2012 PDFDocumento31 páginasM.Ed. Thesis 2012 PDFagmangi33% (3)

- G1 PlanDocumento5 páginasG1 PlanNethaji PoliAún no hay calificaciones

- Foley's Eki PDFDocumento463 páginasFoley's Eki PDFClaude JousselinAún no hay calificaciones

- Teo 2014 SumiDocumento151 páginasTeo 2014 SumiuliseAún no hay calificaciones

- The Spratly Islands DisputeDocumento36 páginasThe Spratly Islands DisputeSuzaku Lee0% (1)

- Lecture Note - ES 1Documento48 páginasLecture Note - ES 1Brian SamirgalAún no hay calificaciones