Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

All Hands On Deck - Prologue Fall 2011

Cargado por

Prologue MagazineTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

All Hands On Deck - Prologue Fall 2011

Cargado por

Prologue MagazineCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

a

Sailors in 1812 ife l

r

By Sarah H. Watkins and Matthew Brenckle

All Hands on Deck

ver wonder if a sailors life is for you? Visitors to All Hands on Deck: A Sailors Life in 1812, the USS

Constitution Museums newest exhibit, can find out. Designed to be both hands-on and minds-on, the exhibit allows families to scrub a deck, swing in a hammock, fire a cannon, and furl a sail as they learn about history together. All Hands on Deck is the culmination of years of research into the lives and experiences of the men who served on board USS constitution at the moment when the ship earned her nickname, Old Ironsides, and became a national symbol that endures today as one of Bostons most famous attractions.

USS Constitution (Old Ironsides) defeated HMS Guerriere on August 19, 1812, and became a national symbol. Left: Life-sized photographs of actors in authentically reproduced costumes populate the exhibit and add a sense of realism to the visitors experience.

Fueled by research conducted at the National Archives, the exhibit brings the past to life using innovative interpretive techniques. Best of all, every aspect is informed by the hard-won experiences of the men and women who lived through the War of 1812. Because of her wartime exploits, the nation has preserved Constitution as a naval monument, a shrine to victories wrested from the mighty Royal Navy. While the ships status as a national symbol has ensured her survival, it has tended to obscure the people who made the ships victories possible. Thousands of individuals lived, worked, and fought on board her. The exhibit interprets Constitution from the inside out, giving voice for the first time to the ships company. By focusing on the people, including common seamen,

officers, and marines, the exhibit allows visitors to look beyond tactics and technology. The exhibit examines sailors motivations for enlisting and how they adjusted to life in the self-contained wooden world. It also offers a glimpse of life ashore, considering who and what the sailors left behind and the impact of separation and loss on seaside communities. As All Hands on Deck demonstrates, when sailors entered the highly regulated, interdependent shipboard community, they were forced to endure psychological and physical hardship for the sake of ship and country. Their shared experiences forged an emotional bond among shipmates and led them to regard their messmates as a surrogate family. For them, the ship was home. The exhibits final section shows how the crews participation in naval victories over Great Britain during the War of 1812 contributed to Americas emerging national identity.The story of Constitution and her crew is particularly timely as our country prepares for the bicentennial of the War of 1812.

All Hands on Deck

Prologue 37

Visitors Prepare to Go to Sea As Sailors on the Constitution

When visitors enter All Hands on Deck, they experience the bustle of a busy Boston waterfront as provisions and livestock are hoisted aboard. Handbills posted on the walls indicate that they are approaching a recruiting office for USS Constitution. Here visitors first encounter life-sized photo cutouts of sailors and civilians. Using the physical descriptions of actual individuals from the timeage, height, eye and hair color, and scars or tattoos, all gleaned from size rolls (physical descriptions and enlistment details of Marine privates and NCOs), prisoner-of-war records, and seaman protection certificateswe sought actors who had the right look and fit the sailors profiles. An extensive review of clothing receipts in Treasury accounts and Navy contract proposals at the National Archives told us

exactly what Constitutions men wore and allowed us to create a wardrobe of handsewn garments. Skilled make-up artists gave the actors the ruddy cheeks and dirty hands of real weather-beaten tars. These figures populate the exhibit and lend an unrivaled level of character and verisimilitude to the surroundings. Outside the House of Rendezvous (temporary recruiting office), visitors see an original broadside notifying citizens that War is declared. Lt. Charles W. Morgan, responsible for recruiting, invites visitors into the waterfront building to serve their country and fight for free trade and sailors rights. Inside, visitors take turns acting as recruiter and recruit. The recruiter asks the recruit a series of questions to gauge his or her

Visitors can swing on a hammock like the ships sailors, try the tough work of scrubbing the deck, and work at furling a sail.

potential as a sailor. Some questions elicit laughs, others looks of disbelief or disgust. For instance, the recruiter asks, Have you ever swung in a hammock? Are you willing to sleep next to 200 of your closest friends who are badly in need of a bath? The recruiter tallies the answers, and the recruit joins the crew. Next, artifacts and text panels prompt visitors to think about what sailors needed to bring to sea with them and what it was like to bid farewell to loved ones. Once on deck, they are welcomed on board by a musket-wielding marine sentry who warns them that they must do their duty or suffer the consequences. The space mimics Constitutions deck, with planking below, rigging above, the bulwarks of the ship on either side, and sounds of the ship and sea.

Fall 2011

Learning to Be the Newest Recruits On Board USS Constitution

New recruits who need clothes can buy supplies from the purser and discover how quickly these purchases consume their wages. Treasury accounts provided the historical prices charged for slops ready-made clothing and other sundries like chocolate, soap, and tobacco. Below decks, the low ceilings and minimal lighting simulate the dark, crowded, stuffy, and wet living quarters of the crew. Visitors can climb into a hammock and swing side by side with their friends. Questions on the beams overhead ask them to think about the lack of personal space and some of the sea miseries experienced by sailors. Across the deck from the hammocks stands a low, black iron stove, a miniaturized version of a ships camboose copied from drawings and descriptions in the Board of Navy Commissioners correspondence. Using faux rations, children can concoct a sailors stew and serve it to their friends. Gathered picnic-style around a black painted cloth, visitors bond over salt pork, ships biscuit, and grog. In the words of one contemporary sailor, messes were little communities of about eight. . . . These eat and drink together, and are, as it were, so many families.

The exhibit All Hands on Deck allows visitors to learn about the experiences and lives of the men who served on board USS Constitution, ca. 1812.

Tough Work Awaits on Deck, And So Does Tough Discipline

Back on deck, the real work begins. Visitors are encouraged to try their hands at typical sailor tasks. They are given a reproduction holystone and told to get on their knees and scrub the deck. To convey different perspectives, this object is seen from the point of view of a sailor for whom it represented daily monotonous labor and the first lieutenant

who felt pride in the glistening ship and saw the advantages of keeping hundreds of men busy each morning. Activities that require teamwork for success, such as furling a sail, highlight the physical skill and mental stamina required to sail a ship. As visitors approach the yard, they see a film showing sailors aloft taking in a sail at sea. The camera moves with the vessel, giving the impression that one is swaying high above the deck. Once visitors step off the ground to balance on the footrope slung below the yard, they work together to pull in a heavy sail. The yard and sail are surrounded by images of sailors working aloft. Nearby, an 1820s journal delineates the station of each crewmember in the top and on the yards. A sailors life is full of strife, goes the old song, and interpersonal conflict was a fact of life on a wooden warship. Discipline in some measure ameliorated shipboard disagreements. Visitors view an original 19thcentury cat-o-nine-tails, which to a sailor represented humiliation, lack of control, and

a constant threat. But from the captains perspective, it was a necessary evil to control the crews bad behavior.

The Effects of Battle on Crew: Glory and the Scars of War

Without well-trained gun crews to aim and fire its many cannon, a warship was useless. Visitors can learn about the training and teamwork required to fire a cannon on Constitution. A video shows Constitutions 21st-century crew demonstrating the steps required to load a gun that weighs nearly 7,000 pounds. Visitors can haul on the lines of a replica 32-pound carronade and see if they are strong enough and fast enough to prepare it for firing. Once the visitor-recruits feel confident that they have what it takes to conquer an enemy in battle, they can enter the battle theater. This multimedia show combines historic images, narration, objects, and faces of sailors illuminated in sequence with the story. In his own words, Seamen David C. Bun-

All Hands on Deck

Prologue 39

nell, an 1812 sailor, describes the tension before battle: The word silence was given we stood in awful impatience. . . . My pulse beat quickall nature seemed wrapped in awful suspensethe dart of death hung as it were trembling by a single hair, and no one knew on whose head it would fall. Other crewmembers share their own sentiments. Young Midshipman Whipple expresses his excitement and a strong sense of patriotism before going into battle for the first time: It appears to me at present that a man must be happy who sacrifices everything for his country . . . should I be so fortunate as to prove serviceable to

my country, I shall be in the zenith of my glory. Whipples words return after the battle: This being the first action I was ever in, you can imagine to yourself what my feelings to hear the horrid groans of the wounded and dying. The battle presentation also explores how combatants attitudes toward their opponents changed after battle. No longer boasting tyrants or faceless monsters, sailors on opposing sides enjoy some moments of camaraderie, even as the surgeons work frantically to remove shattered limbs and staunch the bloody wounds.

All Hands on Deck concludes with the crew and ship returning home to a heros welcome. Here visitors learn what USS Constitution meant to her crew and to the country as a whole and discover the fate of the sailors profiled in the exhibit.

How Do We Know What We Know? Finding Answers at the Archives

Who were the 1,171 men who served on Constitution between 1812 and 1815? How do we resurrect these fellows from the murky depths of history to which theyve been consigned?

Sailor Philip Brimblecoms certificate of disability was one of the documents used to recreate his naval record. He was captured and imprisoned by the British, escaped, and served on board Constitution. Injured in a battle with HMS Java, Brimblecom was granted a six-dollar-per-month pension.

USS Constitutions muster roll for 180910 records the sailors names, including that of Capt. Isaac Hull, date of entry on board, rank, and pay.

At the core of All Hands on Deck lies a major research effort that began in 2001 and that built on 30 years of research by Tyrone G. Martin, former commanding officer of USS Constitution and author of A Most Fortunate Ship (for more of Martins Constitution research, visit www.polkcounty.org). According to scholars who advised the exhibit in its planning stages, no other maritime museum has attempted an in-depth look at the lives of ordinary seamen from a single ship. This approach presented a formidable research challenge. Museum staff mined the records of dozens of repositories across the country. The single most important, however, was the National Archives and Records Administration. Among NARAs many fantastic holdings we find Constitutions logbooks, muster rolls (lists of crew), Marine Corps size rolls, pension records, and official Navy correspondence. Unfortunately, the Navy kept fairly cursory records about the crew. The ships muster rolls recorded a sailors name, rank, date of entry and discharge, and thats about it. No age, no place of origin, no physical descriptionnothing that could help us positively identify them

in other records. Add to this the fact that some, especially those born in Great Britain, might have been serving under false names, and the research challenges become apparent. Luckily, there were other ways to track them down. Paradoxically, the worse a sailors life, the more we know about him. Most men served faithfully for two years and then faded from the record. But a long and often detailed paper trail followed those who suffered life-altering wounds or accidents. The most illuminating source has been the Navy pension applications. If a sailor received a wound or was otherwise disabled in the course of his duty, he was eligible for a monthly stipend from the government (usually equal to half his pay). To receive this payment, however, he had to prove that he had in fact been in the service and that he had been disabled. This means that all the files contain affidavits and declarations by all sorts of people, including the applicant sailor himself. Nearly 150 of Constitutions seamen and officers applied for pensions. Widows and minor orphans of seamen and officers were also eligible for government assistance, and many

applied for relief too. So that gives us a great body of information to work from. When we combine these sources with the usual birth, marriage, and death records, court transcripts, and related documents, we can really begin to recreate what their lives were like. Of the nearly 1,200 who served, we now have good information on about 500. Some of the stories are harrowing and starkly illustrate the dangers of seafaring in the early Republic.

The Unlucky Life of a Sailor: The File on Philip Brimblecom

One of the unfortunates was Philip Brimblecom. Born in Marblehead, Massachusetts, in 1786, he launched his career like many other young men in town, by going to sea in search of cod. In 1809, he gave up the hook and line and shipped on board his uncles schooner, the Springbird, for a voyage to Spain. Here his life took a turn for the worse. Off the coast of Spain, a French privateer captured the Springbird. Unemployed and

All Hands on Deck

Prologue 41

with nowhere to go, Brimblecom shipped on a French merchantman bound for the Indian Ocean. Four days out, a British cruiser took the ship, and Brimblecom found himself a prisoner of the Royal Navy. He was sent to England and imprisoned. In October 1810, Brimblecom managed

to send a letter to his mother, Hannah, in which he described his ordeal. America was not yet at war with England, and Americans should not have been held as prisoners of war. Hannah sent Brimblecoms protection certificate and baptismal record to the American consulate in London to prove that her son was an American citizen. The consul responded that the English considered Brimblecom a prisoner of war because he had been captured while serving on a French privateer. Not pleased by this response, Mrs. Brimblecom had a friend request help from Secretary of State James Madison. Meanwhile, the British took Brimblecom from prison and forced him to serve on board HMS Marlin. Not willing to wait for a diplomatic resolution to his ordeal, he made his escape in the spring of 1812 and boarded a ship bound for Newburyport, Massachusetts. Continuing his string of bad luck, the ship wrecked on the Orkney Islands. Brimblecom and his shipmates

Left: An actor portrays an African American sailor. Free black sailors were integrated into the enlisted shipboard communitysleeping, eating, and working sideby-side with their white counterparts.

traveled from those bleak islands to Scotland, where he boarded an American brig. By then, America had declared war on Britain, and during the voyage across the Atlantic, the British captured Brimblecom again. They took him to Newfoundland, where he was exchanged for a British prisoner in September 1812. At the age of 26, Brimblecom had experienced enough misfortune to last most men several lifetimes. His next step made sense for one who must have seethed with a desire for vengeance. On September 25, 1812, he enlisted as an able seaman on board Constitution. The ship had just returned victorious from an encounter with HMS Guerriere off the coast of Nova Scotia, and her new captain, William Bainbridge, had no trouble recruiting men to serve on the lucky vessel. The ships luck did not rub off on Brimblecom. As Constitution sailed south during October and November, the sailors frequently exercised at the great guns, learning to perform their duties with speed and accuracy.

Below: An online game and educational resource brings the teeming humanity of the ship to life for a virtual audience (www.asailorslifeforme.org). Users can scrub the deck, whack rats in the hold, tell tall tales, steer the ship, and fire a cannon.

Fall 2011

USS Constitution under tow in Boston Harbor.

According to the ships quarter bill, Brimblecom served as the first loader to gun number one on the gun deck. It was a dangerous position, and he did his duty there on December 29, 1812, when Constitution encountered HMS Java off Brazil in a hard-fought battle. In the midst of the action, as Brimblecom bent to load the gun, a British cannonball shattered his arm below the elbow. Surgeon Amos Evans amputated the limb, and although the stump quickly healed, the young sailor remained in constant pain. With only one arm, Brimblecom could not work as a seaman, the only work he had ever known. Twice he wrote to the Navy seeking employment and for an increase in his six-dollar monthly pension, which he and his mother relied on. He complained, some of the rest that was wounded with me has had an addition to their pension money. Brimblecom got a job at the Charlestown Navy Yard in 1816, and at the Portsmouth Navy Yard the following year. By 1820 he was unable to do anything for a living, and since he had no friends on earth, he asked the government to take his request into consideration and look after a poor distressed crippled sailor who for 22 long months . . . [has] never seen a well day. The response, if any, to his

final request is unknown. Philip Brimblecom died of a fever on February 1, 1824, in Marblehead. He was only 37 years old.

The Strange Case of David Debias: A Free Black Wanders into Slavery

The records at the National Archives have also helped resolve at least one mystery. In 1814, an eight-year-old African American boy named David Debias joined Constitutions crew. Debias was born free on Belknap Street in Boston. In the early 19th century, seafaring was one of only a few jobs that offered free African Americans not only a living wage, but also a respectable career with equal pay. Though racism was not absent aboard ships, free black sailors were integrated into the enlisted shipboard communitysleeping, eating, and working side-by-side with their white counterparts. Historians estimate that during the War of 1812, 7 percent to 15 percent of sailors were free men of color. A month after joining Constitutions crew, Debias participated in its victory over two British ships, HMS Cyane and HMS Levant, on the night of February 20, 1815. Transferred to the Levant with the prize crew, he

was taken prisoner when the British recaptured the ship at Porto Praya in the Cape Verde Islands. After a stint in a Barbados prison, he returned to Boston. Debias remained with his parents for some time and then shipped as a sailor on several merchant voyages. In 1821 he again shipped on board Constitution. Commanded by Capt. Jacob Jones, the frigate sailed for the Mediterranean, where the young man no doubt marveled at the wonders of the ancient world. The ship touched at Leghorn, Gibraltar, Malaga, Port Mahon, Genoa, Leghorn, Naples, Malta, Algiers, and Smyrna and finally came home to New York. Debias left the service then and sailed in other merchant ships. Sometime in 1838, his ship docked in Mobile, Alabama. For some unexplained reason, Debias left the ship and started walking north. In Wayne County, Mississippi, he was arrested as a runaway slave. After hearing Debiass story and believing him the victim of a grave injustice, a local lawyer and state senator, Thomas P. Falconer, took up his cause. Falconer wrote to Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson for evidence from the Navy Department in behalf of an individual who has been arrested here as a slave. I have not the least doubt of his freedom, but his appearance may force upon

All Hands on Deck

Prologue 43

him the onus probandi of freedom. He is a stranger in a strange land and from the rigidness of the law in the absence of testimony may be deprived of his liberty. For years, we wondered about the fate of David Debias. Did Secretary Dickerson respond to this request? Was he freed or sold into slavery? Finally, in fall 2010, thanks to archivist Trevor Plante at the Archives, the mystery was solved. On April 17, 1838, Secretary Dickerson forwarded to Falconer an authoritative certificate by the 4th Auditor of the Treasury, proving that David Debias had in fact served on Constitution. Because the Wayne County Court House burned down in the 19th century, all the court records from the 1830s have

been lost. Still, we can hope that this significant piece of evidence was sufficient to free Debias.

The Impact of the Research On Study of the War of 1812

The research into the individuals who served on board Constitution allows the museum to breathe new life into the ships history. By telling the story of life on board USS Constitution through the sailors who experienced it, All Hands on Deck allows visitors to connect to the past in a personal way. One teacher remarked: Its a wonderful way to make history come alive and become real to my fifth graders. As one of my students said this year, history like this is fun, because its about us. The exhibits humanistic viewpoint and participatory approach has demonstrated the potential to change how children view historychildren like Kelly, age 10, who reported, I used to think history was boring, now I it! To expand the reach of our research in advance of the bicentennial of the War of 1812, the USS Constitution Museum launched an online game and educational resource that brings the teeming humanity of the ship to life for a virtual audience (www.asailorslifeforme.org). The award-winning site allows users to experience the life of an 1812 sailor and scrub the deck, whack rats in the hold, tell tall tales, steer the ship, and fire a cannon. The site also includes curriculum material for teachers who want to teach about the War of 1812 and USS Constitution, and Discovery Kits are being made available to public libraries across the country for families to check out. The bicentennial of the War of 1812 provides a singular opportunity to engage all ages in conversation and discovery about USS Constitution and the War of 1812. Thanks to the records available at the National Archives, students and families will

discover that history is about individuals like themselves, just separated by time. Through the USS Constitution Museums exhibit, web site, and library kit, students and families learn that history can be exciting, meaningful, and personally relevant. P Note on Soures

Constitutions 1812 logbooks are microfilmed on Logbooks and Journals of the U.S.S. Constitution, 17981934 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M1030), vols. 3 and 4. The ships muster rolls are microfilmed on Organization Index to Pension Files of Veterans Who Served Between 1861 and 1900 (National Archives Microfilm Publication T829). Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 17981892, are on National Archives Microfilm Publication T1118. Boston Navy Agent Amos Binneys purchasing receipts for Constitution come from the Accounts of the Fourth Auditor of the Treasury, Records of the Accounting Officers of the Department of the Treasury, Record Group (RG) 217, boxes 38 and 39. In Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, RG 127, are size rolls, which record name, rank, birthplace and date, date and length of enlistment, officer who enlisted the marine, height, hair and eye color, complexion, previous occupation, and remarks detailing service in the corps. Clothing proposals sent to the Board of Navy Commissioners can be found in Proposals, Reports, and Estimates for Supplies and Equipment, 18141833, Vol. 4, E-328, Naval Records Collection of the Office of Naval Records and Library, RG 45. Philip Brimblecoms pension application is in War of 1812 Navy Invalid File #201, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, RG 15. His mothers correspondence with James Monroe and his protection certificate are in Letters Received by the Department of State Regarding Impressed Seamen, 17941815, General Records of the Department of State, RG 59. The Bainbridge Battle Bill is in Series 464, box 222 Subject Files 17751910, RG 45. Thomas Falconers 1838 letter to Mahlon Dickerson is in Letters Received by the Secretary of the Navy: Miscellaneous Letters, 18011884 (National Archives Microfilm Publication M124). The secretarys reply is in Entry 6, Miscellaneous Letters Sent (General Letter Books), Vol. 24, page 403, RG 45.

Captain Isaac Hulls sword. Hull commanded Constitution during its battle with the British frigate HMS Guerriere on August 19, 1812.

Author

Sarah H. Watkins is curator and Matthew Brenckle is research historian at the USS Constitution Museum. Founded in 1972, the USS Constitution Museum is a private not-for-profit institution, serving as the memory and educational voice of Old Ironsides. Open 7 days a week, 362 days a year, the museum welcomes more than 300,000 annual visitors free of charge.

To learn more about

The War of 1812 from National Archives records, go to www. archives.gov/research/military, and click on War of 1812. Veterans service records in general, go to www.archives.gov/veterans. A British ships challenge to the USS Constellation to a duel between the frigates in 1815, see www. archives.gov/publications/prologue/2007/spring/.

44 Prologue

Fall 2011

También podría gustarte

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- Aldous Huxley - The Doors of Perception PDFDocumento24 páginasAldous Huxley - The Doors of Perception PDFMike Wentz100% (5)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- The Meaning and Making of EmancipationDocumento215 páginasThe Meaning and Making of EmancipationPrologue Magazine100% (6)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2101)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Moon LandingDocumento29 páginasMoon LandingRamAún no hay calificaciones

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (73)

- Baseball: The National Pastime in The National ArchivesDocumento137 páginasBaseball: The National Pastime in The National ArchivesPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Absent Healing - This Is Where A Person or Group of People SendDocumento14 páginasAbsent Healing - This Is Where A Person or Group of People SendJoanne JacksonAún no hay calificaciones

- Will You Vote?Documento1 páginaWill You Vote?Prologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Web App SuccessDocumento369 páginasWeb App Successdoghead101Aún no hay calificaciones

- 11 Taylor - The Tomb of Paheri at El KabDocumento52 páginas11 Taylor - The Tomb of Paheri at El KabIzzy KaczmarekAún no hay calificaciones

- Lewis Carroll - Photography On The MoveDocumento258 páginasLewis Carroll - Photography On The MoveAlsa Man100% (4)

- Canon 60D Screw Layout Diagram 3Documento1 páginaCanon 60D Screw Layout Diagram 3alexis_caballero_6Aún no hay calificaciones

- Stefan Scharf - EditingDocumento30 páginasStefan Scharf - EditingFoad WMAún no hay calificaciones

- God Is A DJ, Falk Richter EnglishDocumento82 páginasGod Is A DJ, Falk Richter EnglishE. Santander100% (1)

- VXvue User Manual For Veterinary Use - V1.1 - EN PDFDocumento181 páginasVXvue User Manual For Veterinary Use - V1.1 - EN PDFscribangelofAún no hay calificaciones

- The Woman Who VotesDocumento1 páginaThe Woman Who VotesPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Truman Campaign CarDocumento1 páginaTruman Campaign CarPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Truman at Union StationDocumento1 páginaTruman at Union StationPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Jimmy Carter Campaign FlyerDocumento1 páginaJimmy Carter Campaign FlyerPrologue Magazine100% (1)

- Nixon Greets StudentsDocumento1 páginaNixon Greets StudentsPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Ronald and Nancy Reagan in ColumbiaDocumento1 páginaRonald and Nancy Reagan in ColumbiaPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Lady Bird and Lyndon B. Johnson in MinnesotaDocumento1 páginaLady Bird and Lyndon B. Johnson in MinnesotaPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Clinton Whistle Stop TourDocumento1 páginaClinton Whistle Stop TourPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Postcard From The Lady Bird SpecialDocumento1 páginaPostcard From The Lady Bird SpecialPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Jimmy Carter, 1976Documento1 páginaJimmy Carter, 1976Prologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- FDR Campaigns in AtlantaDocumento1 páginaFDR Campaigns in AtlantaPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Housewives For TrumanDocumento1 páginaHousewives For TrumanPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Gerald Ford Campaign SwagDocumento1 páginaGerald Ford Campaign SwagPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- George and Barbara Bush Aboard Air Force IIDocumento1 páginaGeorge and Barbara Bush Aboard Air Force IIPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- George Bush CampaignsDocumento1 páginaGeorge Bush CampaignsPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower Whistle Stop TourDocumento1 páginaDwight and Mamie Eisenhower Whistle Stop TourPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Depression-Era Democratic Party Campaign PhotoDocumento1 páginaDepression-Era Democratic Party Campaign PhotoPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- George W and Laura Bush CampaignDocumento1 páginaGeorge W and Laura Bush CampaignPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- FDR Campaigns in Hyde ParkDocumento1 páginaFDR Campaigns in Hyde ParkPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Betty and Gerald Ford at The RNCDocumento1 páginaBetty and Gerald Ford at The RNCPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Clinton at A Get Out The Vote Rally in Los AngelesDocumento1 páginaClinton at A Get Out The Vote Rally in Los AngelesPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- This Is AmericaDocumento1 páginaThis Is AmericaPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Anti-FDR Campaign ButtonsDocumento1 páginaAnti-FDR Campaign ButtonsPrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

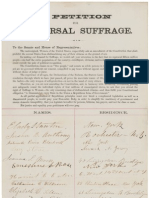

- Petition For Universal SuffrageDocumento1 páginaPetition For Universal SuffragePrologue MagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Walking With Cthulhu 2011 Web PDFDocumento200 páginasWalking With Cthulhu 2011 Web PDFcharm000Aún no hay calificaciones

- American RealismDocumento28 páginasAmerican RealismhashemdoaaAún no hay calificaciones

- Sarix IME Indoor and Environmental Mini Domes: Product SpecificationDocumento6 páginasSarix IME Indoor and Environmental Mini Domes: Product SpecificationElvis Richard Barrera RomanAún no hay calificaciones

- Michael Moskal Plea AgreementDocumento2 páginasMichael Moskal Plea AgreementEmily BabayAún no hay calificaciones

- Đề 06Documento5 páginasĐề 06Micky TrầnAún no hay calificaciones

- FAQs For Aptitude Test and Typing Skill TestDocumento2 páginasFAQs For Aptitude Test and Typing Skill TestVamshi Krishna AllamuneniAún no hay calificaciones

- Introduction To Paintings: by Cathy ChangDocumento18 páginasIntroduction To Paintings: by Cathy ChangSameer MehtaAún no hay calificaciones

- Multimedia ProdDocumento7 páginasMultimedia Prodadam adamAún no hay calificaciones

- BibliographyDocumento5 páginasBibliographyHarrison TurnerAún no hay calificaciones

- Lighting DesignDocumento5 páginasLighting DesignemsAún no hay calificaciones

- Admit Card CTETDocumento2 páginasAdmit Card CTETMukeshsonu111Aún no hay calificaciones

- Jennifer Nance Short Story Final DraftDocumento6 páginasJennifer Nance Short Story Final Draftapi-242579236Aún no hay calificaciones

- Visioffice Measurement FAQDocumento8 páginasVisioffice Measurement FAQQulrafMongkonsirivatanaAún no hay calificaciones

- User Guide QuadraDocumento24 páginasUser Guide QuadraAlina BoticaAún no hay calificaciones

- VL3500 SpotDocumento2 páginasVL3500 SpotofgonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- Finepix s4600-s4800 Manual en PDFDocumento143 páginasFinepix s4600-s4800 Manual en PDFpitulusaAún no hay calificaciones

- Mountain Tribes in Northern LuzonDocumento2 páginasMountain Tribes in Northern LuzonRJ Sumonod Jr.Aún no hay calificaciones

- Similarity of TrianglesDocumento38 páginasSimilarity of TrianglesunikxocizmAún no hay calificaciones

- HHG Housing - Ds enDocumento4 páginasHHG Housing - Ds enLenzy Andre FamelaAún no hay calificaciones

- Tabela de Marcações de Lentes Progressivas: Alfa LuxDocumento10 páginasTabela de Marcações de Lentes Progressivas: Alfa Luxfknakashima8847Aún no hay calificaciones