Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Crime and The 1996 Feature Gravity and Grace. Kraus Has Also Edited A

Cargado por

alexhwangDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Crime and The 1996 Feature Gravity and Grace. Kraus Has Also Edited A

Cargado por

alexhwangCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

a fusion of gossip and theory by Giovanni Intra Chris Kraus, I Love Dick, Semiotexte, 1997, $10.

50 Chris Kraus' first novel, I Love Dick, reads like Madame Bovary as if Emma had written it. Kraus spins out the Emma-syndrome of dissatisfied feminine boredom through a chronicle of the '80s art world. Her book is a damningly intelligent form of "confessional" literature, part love letter and part public document. Kraus, a Los Angeles-based filmmaker and author, is known for her underground films, including the pseudo-documentary How to Shoot a Crime and the 1996 feature Gravity and Grace. Kraus has also edited a series of books for Semiotext(e) that has published writers such as Kathy Acker to Lynne Tillman. I Love Dick is composed of the billet doux written by Kraus and husband, Columbia philosopher Sylvere Lotringer, to their special friend, Dick. As a kind of art-world roman a clef, the novel fuses gossip and "theory." The profanely and lustfully personal coalesces with intellectual ambition and conceit. Kraus' novel -- written in the first person as any good diary is -reads at times as strategically and dispassionately reductive, not unlike the works of Joseph Kosuth, who the author lampoons in one chapter as perhaps the exemplary white male of his generation. I Love Dick is also a genuinely dangerous book. You feel acute pleasure at the misfortune of others when you read it. And you are very pleased at the luxurious distance which is afforded the reader. Chris Kraus' observations and arguments about art, life, love and politics are read through her own experiences, as well the lives of other "cultural producers," many of whom could well feel a little nervous about becoming subjects of this author's hard-core revelations. Many of Kraus' insights are raw, embarrassing and virtually obscene. Indeed, the novel's alleged subject has been recently revealed by New York magazine to be

the cultural critic Dick Hebdige, with whom Kraus falls in love and subjects to a harassing love-letter campaign for months on end. Kraus has certainly invaded privacy -particularly her own. What she has pillaged from the padded cell of "the personal" is transformed into an exceptional literature by virtue of the author's erudition and consciousness of literary form. Kraus' spectacularly exploitative project is rich in thought and style, not to mention scandal. INTERVIEW: GI: Your book is called I Love Dick. Could you tell us about this ... Dick? CK: Well, you know, this Dick is real. He is a real person. And I really fell in love with him, I didn't set out to write a book. And I wanted him to love me too so I started writing letters. 200 of them. And then he didn't answer. And correspondence is entirely compulsive, the addressee is a blank screen. And I wanted to tell him everything, and once I started talking I couldn't stop. GI: Yes, but who is this... CK: Dick? Dick is every Dick, Dick is Uber Dick, Dick is a transitional object. GI: So Dick was the alibi for the novel, kind of waiting in the wings? CK: Dick is an important cultural critic. GI: Love commanded you to write? CK: Oh, Giovanni ... "Love has led me to the point where I now live badly 'cause I'm dying of desire. I therefore can't feel sorry for myself" -{Provencal, 13th century}. Because when you fall in love with someone the greatest rush is that you can be so many more sides of yourself with them than with anyone else in the world. That person makes it possible to most fully be yourself. And then of course there was the element of failure. I was 39 years old, I'd been married to someone else who was famous in the art world, I'd been working as a filmmaker and editor for 15 years, I'd just finished writing and directing a feature, yet no one took

me seriously. I was a Corporate Wife of the Avant-Garde. So when I felt this -- romance -- happening, I decided to take advantage of it. I decided to become a lab rat in my own experiment. There'd been so many Dicks in my life prior to [my husband] Sylvere [Lotringer], mean horse-faced junkie cowboys. GI: Mean horse-faced junkie cowboys? CK: Yeah. The mystique of simplicity and silence. And this had really fucked me up, just like a lot of other women, so I figured if I'm going to do it now, I'd better study it. Revisit it at the Third Remove. It was very Kierkegaard. GI: When did the love letters change into a novel? You started writing, it became more compulsive, and then it must have clicked into a book project. You started to address an audience... CK: Well, I realized that I had a problem. And my problem was, as an artist, I had not been heard. And I didn't want to believe that the problem was my fault. I thought it was cultural. You know, like Deleuze says, life is not personal. Because if success is culturally determined then so is failure. And it seemed to me that a lot of women who were working in a vein similar to mine had also experienced this "failure." So what drove me on was trying to figure out why there was no position in the culture for female outsiders. You know, singular men are geniuses. Singular women are just "quirky." Of course I really have Dick to thank for this, because he gave me someone to write to. GI: There's a literary fashion now for confessional literature. On the one hand your book is confessional, on the other it's a book about the intellectual context of America in the past 25 years. What's the difference? CK: Well, I want to say there isn't any. And that's why this book is a strategic confession. I'm very drawn to the use of the first person. When I started the Native Agents series of books for Semiotext(e) seven years ago, it was to publish the kind of writing that I

liked -- and that writing was entirely in the first person. And yet it was not an introspective, psychoanalytic "I." It was an "I" that was totally alive, because it was shifting. There's a tradition of American poetry that champions and celebrates this -- New York School, the Poetry Project and all of its successors. These people are true geniuses because they're living constantly with ideas, they're fluent in a huge literary tradition. And yet they're often denigrated by academe and the institutionalized avant-garde because these ideas are experienced immediately and personally. GI: So you think, like the '70s feminists thought, that the personal is political? CK: The personal pursued for its own sake is no good. The "I" is only useful to the point that it gets outside itself, gets larger. In writing this, I kept looking for other people's tracks that I was writing in. No one ever does anything for the first time. I discovered that the New Zealand novelist Katherine Mansfield had been there too -- SHE fell in love with Dick, and wrote a story about it. GI: Most of the successful art-world figures who you describe in I Love Dick are pretty fucked up. The whole show is revealed as being pretty dissatisfied.... CK: Yes! GI: So you'd have to reconsider the whole notion of privilege then, wouldn't you? CK: Well, once you call yourself the biggest asshole, you give yourself a lot of freedom. GI: So you put yourself in the abject position? CK: Life had put me in the abject position, so I thought I might as well take advantage of it. GI: So it's a kind of freedom. CK: If no one cares what you have to say, then you can say anything.

GI: So in actual fact you were in the most privileged position. CK: I think so. Yeah! (laughter) GI: I heard a rumor that Dick was threatening to sue you for invasion of privacy. CK: Yes. He's changed his mind and I'm glad. But it seemed very apt and pertinent to the book. Wasn't the question of "privacy" the entire point? Exploding this "right of privacy" that serves patriarchy so well. The artist Hannah Wilke received an injunction on the eve of her first major retrospective from the artist Claes Oldenburg's lawyers. Hannah had lived with Claes for seven years, and one piece of hers features Polaroid snapshots of people from that period of her life. No one fought for her at that time, and she didn't win. Oldenburg managed to erase that part of her. And I thought, the issue of privacy is to female art what obscenity was to male art of the 1960s. And I thought, on this small scale, I have to win. GIOVANNI INTRA is a graduate candidate in criticism and theory at Art Center College of Design, Pasadena.

an excerpt from i love dick by Chris Kraus 2. The Birthday Party Inside out Boy you turn me Upside down and Inside out.... -- late 70s disco song Joseph Kosuth's 50th birthday party last January was reported the next day on Page Six of the New York Post. And everything was just as perfect as they said: about 100 guests, a number large enough to fill the room but small enough for each of us to feel among the intimates, the chosen. Joseph and Cornelia and their child had just arrived from Belgium; Marshall Blonsky, one of Joseph's closest friends, and Joseph's staff had been planning it for weeks. Sylvere and I drove down from Thurman. I dropped him off outside the loft, parked the car and arrived at Joseph's door at the same moment as another woman, also entering alone. Each of us gave our names to Joseph's doorman. Each of us had names that weren't there. "Check Lotringer," I said. "Sylvere." And sure enough, I was Sylvere Lotringer's "Plus One" and she was someone else's. Riding up the elevator, checking makeup, collars, hair, she whispered, "The last thing you want to feel before walking into one of these things is that you're not invited," and we smiled and wished each other luck and parted at the coat-check. But luck was something that I didn't feel much need for because I had no expectations: this was Joseph's party, Joseph's friends, people, (mostly men, except for female art dealers and us Plus-Ones) from the early '80s art world, so I expected to be patronized and ignored. Drinks were at one end of the loft; dinner at the other. David Byrne was wandering across the room, as tall as a Moorish king in a magnificent fur hat. I stood next to Kenneth Broomfield at the bar and said a tentative hello; he hissed and turned

away. A tighter grip around the scotch glass, standing there in my dark green Japanese wool dress, high heels and make up ... But look! There's Marshall Blonsky! Marshall greets me at the bar and says that seeing me reminds him of a party we attended some 11 years ago when I was Marshall's date. And of course he would remember, because the party was given by Xavier Fourcade to celebrate the publication of Marshall's first book, On Signs, at Xavier's Sutton Place townhouse. It was late winter, early spring, Aquarius or Pisces and I remember guests tripping past the caterers and staff to walk around the green expanse of daffodils and bunny lawn that separated us from the river. David Salle was there, Umberto Eco was there, together with a stable-load of Fourcade's models and a reviewer from the New York Times. At that time I was living in a tenement on Second Avenue and studying charm as a possible escape. Could I be Marshall Blonsky's perfect date? I'd given up trying to be as sexual as Liza Martin but I was small-boned, thin, with a New Zealand accent trailing off to something that sounded vaguely mid-Atlantic. Perhaps something could be done with this? By then I'd read enough that no one guessed I'd never been to school. Marshall and I'd been introduced by our mutual friend Louise Bourgeois. I loved her and he was fascinated by her iron will and growing fame. "It is the ability to sublimate that makes an artist," she told me once. And "the only hope for you is marrying a critic or an academic. Otherwise you'll starve." And in the interest of saving me from poverty, Louise had given me, for this occasion, the perfect dress: a straight wool boucle pumpkin colored shift, historically important, the dress she'd worn accompanying Robert Rauschenberg to his opening on East 10th ... Most of Marshall's friends were men -- critics, psychoanalysts, semioticians -- and he liked that he could walk me round the room and I'd perform for them, listening, cracking jokes in their own special languages, guiding the conversation back to

Marshall's book. So French New Wave. Being weightless and gamine, spitting prettily at rules and institutions, a talking dog without the dreariness of a position to defend. Dear Dick, It hurts me that you think I'm "insincere." Nick Zedd and I were both interviewed once about our films for English television. Everyone in New Zealand who saw the show told me how they liked Nick best 'cause he was more sincere. Nick was just one thing, a straight clear line -Whoregasm, East Village gore 'n porn -- and I was several. And-and-and. And isn't sincerity just a denial of complexity? You as Johnny Cash driving your Thunderbird into the Heart of Light. What put me off experimental-film-world feminism, besides all it's boring study groups on Jacques Lacan, was it's sincere investigation into the dilemma of the Pretty Girl. As an Ugly Girl it didn't matter much to me. And didn't Donna Haraway finally solve this by saying all female lived experience is a bunch of riffs, completely fake, so we should recognize ourselves as Cyborgs? But still the fact remains: You moved out to the desert on your own to clear the junk out of you're life. You are trying to find some way of living you believe in. I envy this. Jane Bowles described this problem of sincerity in a letter to her husband Paul, the "better" writer: August 1947 Dearest Bupple, ... The more I get into it, the more isolated I feel vis-a-vis the writers who I consider to be of any serious mind. I am enclosing this article entitled New Heroes by Simone de Beauvoir. Read the sides that are marked pages 121 and 123. It is what I have been thinking at the bottom of my mind all this time and God knows it is difficult to write the way I do and yet think their way. This problem you will never have to face because you have always been a truly isolated person so that whatever you write will be good because it will be true which is not so in my case. You immediately receive

recognition because what you write is in true relation to yourself which is always recognizable to the world outside. With me who knows? When you are capable only of a serious approach to writing as I am it is almost more than one can bear to be continually doubting one's sincerity.... Reading Jane Bowles' letters makes me angrier and sadder than anything to do with you. Because she was just so brilliant and she was willing to take a crack at it -- telling the truth about her difficult and contradictory life. And because she got it right. Even though, like the artist Hannah Wilke, she hardly found anybody to agree with her in her own lifetime. You're the Cowboy, I'm the Kike. Steadfast and true, slippery and devious. We aren't anything but our circumstances. Why is it men become essentialists, especially in middle age? And at Joseph's party time stands still and we can do it all again. Marshall walks me over to two men in suits, a Lacanian and a world banker form the UN. We talk about Microsoft and Bill Gates and Timothy Leary's brunches until a tall and immaculately gorgeous WASP woman joins us and the conversation parts away from jokes about interest rates and transference to make room for Her.... (As I write this I feel very hopeless and afraid) Later Marshall made a birthday speech for Joseph that he'd been scribbling on all night. And Glenn O'Brien, looking like Steve Allen at the piano, performed a funny scat-singing recitative about Joseph's legendary womanizing, wealth and art. Everyone clapping, laughing, camp but serious and boozy like in the film The Girl Can't Help It, men in suits playing TV beatniks but where's Jayne Mansfield as the fall girl? Then David Byrne and John Cale played piano and guitar and people danced. Sylvere got drunk and teased Diego, something about politics, and Diego got mad and tossed his drink in Sylvere's face. And Warren Niesluchowski was there, and John

and Anya. Later Marshall marshaled a gang of little men, the banker, the Lacanian and Sylvere, to the card room to drink scotch and talk about the Holocaust. The four looked like the famous velvet painting of card-playing dogs. And it got late and someone turned on some vintage disco, and all the people young enough never to've heard these songs the first time round got up and danced. Funky Town, Le Freakand Inside Out.... The songs that played in topless clubs and bars in the late '70s while these men were getting famous. While I and all my friends, the girls, were paying for our rent and shows and exploring "issues of our sexuality" by shaking to them all night long in topless bar. For information on purchases of I Love Dick, contact amazon.com, or telephone Small Press Distribution at (800) 869-7553.

También podría gustarte

- Alone with the Horrors: The Great Short Fiction of Ramsey Campbell 1961-1991De EverandAlone with the Horrors: The Great Short Fiction of Ramsey Campbell 1961-1991Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (5)

- Del Lagrace Volcano and Ulrika Dahl Femmes of Power Exploring Queer FemininitiesDocumento191 páginasDel Lagrace Volcano and Ulrika Dahl Femmes of Power Exploring Queer FemininitiesClaudia GordilloAún no hay calificaciones

- Broad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Art and Made History (in That Order)De EverandBroad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Art and Made History (in That Order)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (33)

- Ev'ry Time We Say Goodbye-SATB, SATB, A Cappella-$2.10Documento10 páginasEv'ry Time We Say Goodbye-SATB, SATB, A Cappella-$2.10alexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Private Parts, Public WomenDocumento4 páginasPrivate Parts, Public WomenalexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Conversation With Kathy AckerDocumento11 páginasConversation With Kathy AckerImpossible MikeAún no hay calificaciones

- WS IDocumento3 páginasWS IStanislav Zimin100% (1)

- Sample Exercise Remembering-SnowDocumento2 páginasSample Exercise Remembering-SnowIulia Grigoriu50% (2)

- On VacationDocumento10 páginasOn VacationShalyce WoodardAún no hay calificaciones

- 2018 Finnegan J PHDDocumento329 páginas2018 Finnegan J PHDRoss BaroAún no hay calificaciones

- The Calligrapher by Edward Docx - Discussion QuestionsDocumento5 páginasThe Calligrapher by Edward Docx - Discussion QuestionsHoughton Mifflin HarcourtAún no hay calificaciones

- The Shocking Miss Pilgrim: A Writer in Early HollywoodDe EverandThe Shocking Miss Pilgrim: A Writer in Early HollywoodCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (5)

- Leslie Fiedler - What Was Literature - Class Culture and Mass Society-Simon and Schuster (1982)Documento255 páginasLeslie Fiedler - What Was Literature - Class Culture and Mass Society-Simon and Schuster (1982)Jan ČapekAún no hay calificaciones

- Terror to the End: The Last Day in the Life of Charles Dickens in His Own Words (More or Less)De EverandTerror to the End: The Last Day in the Life of Charles Dickens in His Own Words (More or Less)Aún no hay calificaciones

- Santiago Del Rey - Auster QuimeraDocumento5 páginasSantiago Del Rey - Auster QuimeraEsther Bautista NaranjoAún no hay calificaciones

- The Professor and the Prostitute: And Other True Tales of Murder and MadnessDe EverandThe Professor and the Prostitute: And Other True Tales of Murder and MadnessCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (6)

- Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?: StoriesDe EverandWhatever Happened to Interracial Love?: StoriesCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (57)

- The Dreamer Deceiver: A True Story about the Trial of Judas Priest for Deadly Subliminal Messaging (The Stacks Reader Series)De EverandThe Dreamer Deceiver: A True Story about the Trial of Judas Priest for Deadly Subliminal Messaging (The Stacks Reader Series)Calificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- Delphi Complete Works of Winston Churchill IllustratedDe EverandDelphi Complete Works of Winston Churchill IllustratedAún no hay calificaciones

- Introduction: The History of Semiotext (E)Documento4 páginasIntroduction: The History of Semiotext (E)alexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Picture of Dorian GrayDocumento19 páginasPicture of Dorian Grayzitouniryma21Aún no hay calificaciones

- LB Interview For SiAWF1Documento8 páginasLB Interview For SiAWF1Leigh BlackmoreAún no hay calificaciones

- Philip Parte 2Documento199 páginasPhilip Parte 2nicolasAún no hay calificaciones

- Letters from Amherst: Five Narrative LettersDe EverandLetters from Amherst: Five Narrative LettersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (1)

- City of Discontent: An Interpretive Biography of Rachel LindsayDe EverandCity of Discontent: An Interpretive Biography of Rachel LindsayCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1)

- The Night My Friend: Stories of Crime and SuspenseDe EverandThe Night My Friend: Stories of Crime and SuspenseCalificación: 3 de 5 estrellas3/5 (1)

- An Interview With Philip K Dick at Metz France SF FestivalDocumento12 páginasAn Interview With Philip K Dick at Metz France SF FestivalFrank BertrandAún no hay calificaciones

- Shock TreatmentDocumento25 páginasShock TreatmentCity Lights100% (1)

- Entrevista Lethem DickDocumento21 páginasEntrevista Lethem DickFicci OramaAún no hay calificaciones

- Introduction To Objectivism Handbook SampleDocumento99 páginasIntroduction To Objectivism Handbook Samplemarcomanconi03Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ligotti Interview in Subterranean MagazineDocumento8 páginasLigotti Interview in Subterranean Magazineewinig100% (1)

- The Manhattan Project: A Theory of a CityDe EverandThe Manhattan Project: A Theory of a CityCalificación: 2.5 de 5 estrellas2.5/5 (1)

- Rowell, Interview With DelanyDocumento21 páginasRowell, Interview With DelanyTomasz BasiukAún no hay calificaciones

- Ensayos de Teatro de Arthur MillerDocumento6 páginasEnsayos de Teatro de Arthur Millerewb0tp4y100% (1)

- Cross Client PresentationDocumento180 páginasCross Client PresentationNayan ChudasamaAún no hay calificaciones

- Literary Rogues: A Scandalous History of Wayward AuthorsDe EverandLiterary Rogues: A Scandalous History of Wayward AuthorsCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (24)

- The Quests of Simon Ark: And Other StoriesDe EverandThe Quests of Simon Ark: And Other StoriesCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- Writers On WritingDocumento23 páginasWriters On WritingStephenConrad100% (4)

- James Joyce's Dubliners: An Introduction by Wallace Gray: "Araby"Documento13 páginasJames Joyce's Dubliners: An Introduction by Wallace Gray: "Araby"salvador guideAún no hay calificaciones

- In Stoner's mind: to be John Williams: Discovering the american authorDe EverandIn Stoner's mind: to be John Williams: Discovering the american authorAún no hay calificaciones

- Rhapsody Blue: George GershwinDocumento1 páginaRhapsody Blue: George GershwinalexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- 样张 加勒比海盗组曲Documento1 página样张 加勒比海盗组曲alexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- 样张 Arban TromboneDocumento1 página样张 Arban Trombonealexhwang0% (1)

- Kraus 2003 BDocumento3 páginasKraus 2003 BalexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- 样张1 Dan Coates Complete Advance 酒店、咖啡厅钢琴师必备Documento1 página样张1 Dan Coates Complete Advance 酒店、咖啡厅钢琴师必备alexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- 样张 仙境传说Ro 原声音乐钢琴谱 游戏音乐钢琴谱 Ragnarok OnlineDocumento1 página样张 仙境传说Ro 原声音乐钢琴谱 游戏音乐钢琴谱 Ragnarok OnlinealexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Kraus 2002 DDocumento3 páginasKraus 2002 DalexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- 样张 Dan Coates complete advance 酒店、咖啡厅钢琴师必备Documento1 página样张 Dan Coates complete advance 酒店、咖啡厅钢琴师必备alexhwang0% (2)

- Kraus 2002 eDocumento2 páginasKraus 2002 ealexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Kraus 2002 BDocumento3 páginasKraus 2002 BalexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Kraus 2002 FDocumento1 páginaKraus 2002 FalexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Lee & Elaine: by Ann RowerDocumento3 páginasLee & Elaine: by Ann RoweralexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Kraus 2002 CDocumento3 páginasKraus 2002 CalexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Let's Call The Whole Thing OffDocumento3 páginasLet's Call The Whole Thing OffalexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Kraus 2001 eDocumento1 páginaKraus 2001 ealexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Art in America, October, 2001: America The Transient - Jane DicksonDocumento4 páginasArt in America, October, 2001: America The Transient - Jane DicksonalexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Kraus 2001 LDocumento4 páginasKraus 2001 LalexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Kraus KleinDocumento2 páginasKraus KleinalexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Introduction: The History of Semiotext (E)Documento4 páginasIntroduction: The History of Semiotext (E)alexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Jack ADocumento3 páginasJack AalexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Row, Has Been Reissued..Documento7 páginasRow, Has Been Reissued..alexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Gummo Opens at L.A.'s Patrick PainterDocumento5 páginasGummo Opens at L.A.'s Patrick PainteralexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Composition Processes (1978)Documento13 páginasComposition Processes (1978)alexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Crap Shoot - 'Chance: Three Days in The Desert'Documento3 páginasCrap Shoot - 'Chance: Three Days in The Desert'alexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Klein ADocumento2 páginasKlein AalexhwangAún no hay calificaciones

- Kryptek Step by StepDocumento2 páginasKryptek Step by StepJohn NewberryAún no hay calificaciones

- Mobile Communications: Manuel P. RicardoDocumento16 páginasMobile Communications: Manuel P. RicardoNagraj20Aún no hay calificaciones

- Smpte 292M: InfrastructuresDocumento17 páginasSmpte 292M: InfrastructuresMuhammad Hassan KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Jump To Navigationjump To Search: Kasautii Zindagii Kay Chandrakanta Bigg Boss 6 Comedy CircusDocumento4 páginasJump To Navigationjump To Search: Kasautii Zindagii Kay Chandrakanta Bigg Boss 6 Comedy Circusshiva balramAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 4Documento13 páginasChapter 4Ryan SuarezAún no hay calificaciones

- BNI Vision April 2023 Roster BookDocumento16 páginasBNI Vision April 2023 Roster BookTushar MohiteAún no hay calificaciones

- Ravioli RecipeDocumento2 páginasRavioli RecipeViewtifulShishigamiAún no hay calificaciones

- CLM-WP ReadMe - 3 - To CustomizeDocumento4 páginasCLM-WP ReadMe - 3 - To CustomizeGrudge MindlessAún no hay calificaciones

- 127 Character Mantra (Parvidhya Bhakshini Mantra)Documento5 páginas127 Character Mantra (Parvidhya Bhakshini Mantra)Lord MuruganAún no hay calificaciones

- Technical Service Information: Automatic Transmission Service GroupDocumento2 páginasTechnical Service Information: Automatic Transmission Service GroupLojan Coronel José HumbertoAún no hay calificaciones

- Bose Marketing ProjectDocumento28 páginasBose Marketing ProjectShirish Aparadh91% (11)

- Gb9/Db: Phase 2: Jazz Guitar With JaneDocumento2 páginasGb9/Db: Phase 2: Jazz Guitar With JaneAeewonge1211Aún no hay calificaciones

- MenuDocumento10 páginasMenuRindelene A. CaipangAún no hay calificaciones

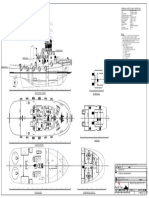

- Principal Particulars - Keppel Bay: E 13.8.15 C.G. Vessel Up-Dated To New Name and LayoutDocumento1 páginaPrincipal Particulars - Keppel Bay: E 13.8.15 C.G. Vessel Up-Dated To New Name and LayoutmanjuAún no hay calificaciones

- Toshiba Copiers Reset ErrorDocumento4 páginasToshiba Copiers Reset ErroranhAún no hay calificaciones

- Features: Technical SpecificationsDocumento10 páginasFeatures: Technical SpecificationsAnonymous BkmsKXzwyKAún no hay calificaciones

- Save The Crew - Stadium ProposalDocumento20 páginasSave The Crew - Stadium ProposalFelipe VargasAún no hay calificaciones

- Elliott Carter Other Chamber Works Sonata For Flute, Oboe, Cello and HarpsichordDocumento10 páginasElliott Carter Other Chamber Works Sonata For Flute, Oboe, Cello and HarpsichordJuliano SilveiraAún no hay calificaciones

- Presentation On SpaDocumento6 páginasPresentation On SpaArunav KashyapAún no hay calificaciones

- WMIListDocumento16 páginasWMIListsrinivasableAún no hay calificaciones

- Guia Preguntas IGA (Wizard of Oz)Documento7 páginasGuia Preguntas IGA (Wizard of Oz)Isabella BrollAún no hay calificaciones

- The Second ConditionalDocumento3 páginasThe Second ConditionalAngela Calatayud50% (2)

- Logitech Device List v2Documento10 páginasLogitech Device List v2DennyHalim.comAún no hay calificaciones

- The Reason For Joy Chord SheetDocumento3 páginasThe Reason For Joy Chord SheetMico SylvesterAún no hay calificaciones

- Student ResourceDocumento36 páginasStudent Resourceapi-317825538Aún no hay calificaciones

- Habanera CARMEN Vocal ScoreDocumento2 páginasHabanera CARMEN Vocal ScoreLuz Shat0% (1)

- Module 1 - Computer Fundamentals PPTDocumento54 páginasModule 1 - Computer Fundamentals PPT77丨S A W ً100% (1)