Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Essays On The Efficient Market Hypothesis

Cargado por

Josh CarpenterDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Essays On The Efficient Market Hypothesis

Cargado por

Josh CarpenterCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

ECO 320v Computable Economics Dr.

Mark McBride Joshua Carpenter

Essays on the Efficient Market Hypothesis and Computational Economics Throughout the course of economic history there have been many thoughts and theories developed that have been accepted as truth right after their introduction. But over the course of time and with a more in depth testing, those same thoughts and ideas were challenged by a more informed body, demolishing the very foundation in which they stood. The efficient market hypothesis is no different and may serve as the next example of a widely accepted precept in finance that has been tested and found to be set upon an unstable foundation. These essays attempt to examine two stances on the efficient market hypothesis and the cost and benefits of using agent-based computational economics as a tool for financial market efficiency. The first essay analyzes an article by Burton G. Malkiel. This work is a general defense against those who feel there are flaws in the efficient market hypothesis. He highlights different works that have been done by the EMHs adversaries and addresses empirical concerns about their findings. In the second essay we look at an article by J. Doyne Farmer and Andrew W. Lo. This article explores recent advances in the quantitative modeling of financial markets. The authors also expand on the evolutionary framework of those markets and the interaction between its components as well as address the efficient market hypothesis from a behavioral point of view. The third essay addresses two articles; one by Mark Buchanan and the other by Farmer and Duncan Foley. Both articles address the need of agent-based computer models in real world settings, the different ways they could be used, and the approaches that are being used today. Finally, the fifth essay highlights an article by Edward P.K. Tsang and Serafin MartinezJaramillo, and attempts to define the scope and agenda of research in computational finance.

An Essay on Efficient Markets Burton G. Malkiel explored specific questions which addresses concerns with identifying patterns in the stock market. The idea was that if there were patterns in the stock market how would they be found. When a specific pattern was found, he then raised the question: is that pattern able to be exploited, if so how exploitable is it? In the article, he elucidates his view of the efficient market hypothesis. That is, all subsequent price changes represent random shifts from previous prices and if information is unimpeded and immediately reflected in the stock prices, then tomorrows price change will reflect only tomorrows news and it will be independent of the price changes today. And because prices fully reflect all known information the uninformed investors will achieve a rate of return that is just as generous as that obtained by expert investors. In supporting his claim Malkiel brings up several questions about the research performed by those who have tested the efficient market hypothesis. The majority of his article is directed toward behavioral economists and psychologists who believe there are predictable correlations within the stock market that can be exploited to obtain returns in excess or in other words the market is inefficient. The first question he addresses is whether short-run momentum patterns in the stock market are able to be identified or measured by using either a quantitative (technical) approach or a fundamental approach. The quantitative approach uses empirical data to postulate a predicted price of a stock or stock index. The fundamental approach evaluates the health of a company by looking at its balance sheet and/or other pertinent fundamental indicators of a companys overall health.

Malkiel states that the economists and psychologists in the behavioral finance field believe that short-run momentum is consistent with psychological feedback mechanisms. For example, as stock prices rise, investors are drawn into the market in a kind of bandwagon effect seeing that there are potential gains in buying stocks. Another possible explanation of short-run momentum patterns is that investors tend to underreact when new information is presented. The author believes that several factors should prevent us from concluding that markets are inefficient by using the above examples as a reference. First, the author suggests that the economic significance of the behavioralists model needs to be addressed. He notes that the transactions costs of investing limits momentum and impedes any likely trading strategy that will beat a buy-and-hold strategy. He provides support for this claim by referring to studies which show that momentum investors do not realize returns. Additionally, he explained that by using a sample taken from momentum investors, the data suggested that they did far worse than buy-and-hold investors, even during a period of positive momentum. Moreover, he said it was the large transactions costs that were involved in finding existing momentum that caused their deficiency. The second point the author makes is that there is little evidence showing that the bandwagon effect occurs in a systematic way that allows it to be exploited. Malkiel supports his case by citing a study performed by Eugene Fama in 1998 that sought to determine whether stock prices responded to information efficiently. The study found that the underreaction to information was about as common as the overreaction and that post-event returns that were

abnormal were as frequent as the reversals. Therefore, the data from that study only supports his claim that markets run efficiently. One important question is whether there are predictable patterns that are consistent over time. The issue with finding exploitable patterns is whether they are patterns that can be applied over time, or if it is time specific. For example, a pattern exploited in 1990 could produce excess returns, but in 2000 it produced negative returns. As the author states, many predictable patterns seem to disappear after they are published in the finance literature and these patterns werent capable of guaranteeing consistent excess returns. Another example used to show this was the thought that there were patterns or anomalies in certain days of the week or times of the season. The general problem the author states is that there isnt any consistency, at least not enough to rely on from a period to period basis. Further, the effects are miniscule compared to transactions costs accrued by trying to exploit them. In the field of finance it is claimed that valuation ratios may provide considerable insight in predicting future stock returns. Malkiel addresses the idea of predicting future returns from initial dividend yields, market returns from initial price-earnings multiples, short-term interest rates, and risk premiums. In short, his first example shows that investors earned a higher rate of return from the stock market when they purchased a market basket of equities with an initial dividend yield that was relatively high and relatively low future rates of return when stocks were purchased at low dividend yields. Malkiel concludes that the dividend yields of stocks tend to be high when interest rates are high, as well as the converse. He explains further that the use of dividend yields to predict future returns hasnt been effective since the mid-1980s. Also,

companies today may be taking a new approach using creative methods like accelerate share repurchasing programs. This in itself would render the dividend yields utility for predicting future returns. Concerning the prediction of market returns from initial price-earnings ratio, studies have found that investors have tended to earn larger long-horizon returns when purchasing a market basket of stocks at relatively low price-earnings multiples. But Malkiel dispels this by giving a current example that shows the inability of the mentioned study to apply that same logic at a later date. As far as interest rates and risk premiums are concerned, he admits that it is far from clear that any of the results given can be used to generate profitable strategies. When valuing a stock there is a belief that an important key to prediction could lay in fundamental aspects of a firm. That is, the characteristics and different valuation parameters of a firm. One of those ways is the tendency of portfolios made up of smaller stocks to achieve a higher monthly average than those of larger stocks. The research performed on this subject has discrepancies. If a researcher would examine the long-run performance of small company stocks, she would be measuring the performance of only the companies that have survived in that long-run time frame, thus, only blurring the predictability of long-run returns. The author concludes that although the data are statistically significant, they still show no evidence that they can be used to predict stock prices in different time periods other than those in which the data were drawn from. He goes on and says that even if there were patterns that existed which allowed investors to earn excess returns, they could follow the past so-called patterns and self-destruct in the future. Other issues he brings up are those in data mining. He

suggests that with the ease of experimenting with almost any type financial data, investigators are bound to find some statistically significant correlation whether or not it is meant to be teased out or not. Finally, he explains that as times passes and empirical techniques become more sophisticated there will be documentation of further apparent departure from efficiency.

An Essay on the Quantitative Modeling of Financial Markets There have been several recent advances in the quantitative modeling of financial markets. Farmer and Lo explain how financial agents can compete and adapt, but not necessarily optimally. When looking at other conventional models used today, it is this aspect that sets agent-based computation economics apart from current economic theory. In a perfect world there would be a simple answer for the question of market efficiency. Moreover, there would also be a simple answer for finding ways to predict future earnings. The need for instruments that predict future economic conditions are well overdue. Unfortunately, finding an answer for these economic concerns are difficult and very complex. Modern economic theory, although complex, only serves as a simplified version of a super-complex system which harbors what seems like an infinite amount of variables. This simplified approach views models only from a post-event perspective and does not account for those variables that cannot, or are hard to measure. The efficient market hypothesis states that price changes are unforcastable if they incorporate the expectations and information of all market participants. As Farmer and Lo state, the EMH is counter-intuitive and contradictory. That is, the most efficient market is one in

which the price changes are completely random and unpredictable so that no one can receive excess returns because the market already reflects all available information and all profits have been captured. Several studies have shown that prices are not completely random, which would violate the EMHs principle rule prices are unpredictable and random. Consequently, this leads to a disagreement within the economics academic community. This, though, raises the question about whether some anomalies are just isolated incidents or can the market be beaten. Specifically, what about some of some of the high-profile portfolio managers or successful investment firms? These types of discrepancies lead us to the question of whether or not the EMH is able to withstand the scrutiny. The issue noted in this article refers to the testing of the EMH. In order to test the EMH you would have to deal several auxiliary hypotheses as well as additional structure in the model investors preferences, the structure information. Additionally, an issue with the EMH arises with assuming that investors make fully rational decisions. Especially since the decisions made are by agents that are perfectly informed, not mentioning the fact that they are assumed to make the correct decision. This article suggests that, yes agents can make good decisions, but not perfect decisions. They cite an example which compares an agents efficiency with the concept of efficiency used in physics. That is, the fraction of available energy converted into useful work. Thus, someone would prefer a refrigerator with 40% efficiency over one that has 35% efficiency, but no one would expect 100% efficiency. This topic as it pertains to financial markets is still in the beginning stages of research.

Another approach this article takes is by applying the efficient market hypothesis to other aspects where profits are possible to those who have the competitive advantage. When the EMH is applied to aspects other than the financial market, there is a vast deficiency found. For example, through research and development a firm can develop a vaccine for the AIDS virus. If this happens and the profits earned are in the billions of dollars, do we assume that this is just an appropriate reward for the R&D, or could that be classified as excess returns? The point is that financial markets should not be different in principle, but only in degree. The disagreements that surround the EMH have led to the development of new ideas for research. One of the most interesting and, according to the authors, one of the most promising ideas stems from a biological perspective. This idea breaks away from the conventional modeling where it is assumed that the households making decisions are rational. This model accounts for the irrationality of agents within a complex system, modeling markets, societies, or entire economies. Another aspect that these models capture is the fact that agents evolve and learn. This is something that the simple model of modern economics has yet to account for. Nor does the modern model account for the manner in which psychology influences the decisions of a household. These agent-based models are meant to capture those complex behavioral tendencies and dynamics that make market realistic relative to the actual setting. Financial markets are view as a living organism or an evolving ecology of trading strategies. What is so interesting is that the financial markets actions are analogous to what an individual agent does within the market. That is, even though there are patterns in individual behavior, the integration of each individuals actions in concert creates patterns in the whole.

Although different in the format in which each issue is approached, these models that attempt to explain some characteristic of financial markets are directed at interpreting the EMH in their own words. Since there is no lack of quantitative data, the opportunities are endless with ACE and its almost certain that there will be considerable advances which link biological and evolutionary ideas to the financial market.

An Essay on the Need for Agent-Based Computable Economic Models In light of the past financial meltdown there seems to be a consensus that breaks partisanships and socioeconomic barriers. The idea of having another catastrophe in the financial market is enough to send chills down any Wall Street investors spine. Conventional methods have yet to prove that it can withstand the expected level of predictability needed to provide confidence not experiencing this again. In his article Meltdown Modelling Buchanan uncovers an approach not as well publicized in the financial community as those methods currently used on a daily basis. As Buchanan explains, the current methods used today are only methods that can draw from past experiences. There are several issues with the current models used to monitor and predict future happenings. These models have a hard time accounting for nonlinearities and patterns that can only come from agents interacting with each other. Another issue faced by academic economists is the idea of bringing outside help in from other realms of study to give a fresh perspective. The idea is to get a fresh perspective on the issues which could provide a way to purge ideological tendencies and failed assumptions. Generally, this is meant to help the situation. But, some economists argue whether it is a good

idea to invite someone in that doesnt have the experience within economics and finance to spur scientific progress. Additionally, there is also the general distrust in agent-based computer models. In general, this is due to a lack of understanding of what these models do. As a real-life example, Buchanan mentions an experience with the NASDAQ chief Mike Brown. At the time, NASDAQ faced the situation of switching from fractional stock prices to numbers that provided the price in decimals. The main goal was to improve the accuracy of stock prices and this change also allowed prices to change by smaller increments. The consequences of how this would affect trading strategies were unknown. Using an agent-based model the idea was tested. Because of this test the NASDAQ team was able to address inefficiencies in the magnitude of the price increments, thus using the agent based model as a market wind tunnel. The two models the United States government, the Foley and Farmer article says, has flaws. The first model deals with the inaccuracy of econometric models, which is only able to accurately forecast a couple quarters ahead as long as economic conditions stay more or less the same. The other model rules out any type of crises, the model is founded upon the assumption that it is a perfect world. Agent-based models account for petri dish type growth predictions, not relying on the assumption that the world is perfect and everyone makes perfectly informed, rational decisions. These two benefits in themselves provide a useful tool for modeling several different portions of the economy. A few mentioned in this particular article are models of financial markets which provide a plausible explanation for bubbles and crashes, simulation of firm dynamics which models how firms grow and decline as workers move between them, and credit sector models.

The idea that an entire economy could be modeled may be a little far off, but with continual achievements in the modeling of the tendencies of different sub-sets of an economy, it is possible that in the aggregate each model can be tweaked and linked to create some sort of organism which closely resembles our very own economy.

An Essay on the Scope and Agenda of Agent-Based Computational Finance Research Twenty years ago computer systems were substantially slower and less able to compute complex data compared to todays machines. The advancements with computer systems today are improving at an amazing rate. With improvement in computer technologies, there comes a positive externality which provides us with the ability to compute complex data, sometimes, from the convenience of our own home. The same stands for the growth in the use of computation programs to improve firms disposition as a profitable company. As the first spreadsheet ramped up capabilities of analyzing several complex datasets that in the past took up a great amount of time, there are also other advancements which in the near future could help control costs or generate revenue as much as that first spreadsheet did. Modern economic theory and fundamentals have generally been accepted due to their ability to accurately simplify a complex condition in order to understand it better. But as time goes on, so does the complexity of the systems in which the principles of economics and finance were founded upon. This raises the question to whether or not these simple models, maintaining simple assumptions can continually be used as the systems in which they model increase substantially in complexity. Agent-based models have an agenda to challenge these thoughts and

assumptions by providing a way to account for the irrationality of agents in a complex system. Therefore, challenging the very foundation of the efficient market hypothesis. Moreover, it also provides a way to set certain agent-specific assumptions to model system-specific results. Another part of an agent-based models agenda is to understand financial markets. This is seen in the vast amount of models that represent different markets within an economy, such as the labor market we spoke previously about or even an orchestrated artificial stock market such as the Sant Fe Stock Market. There is also a certain amount of importance weighted on agents that evolve. This is found in the construction and attempts to model an accurate depiction of competitive agents. ACE models are also used to study the microstructure of a market which is used to developed different trading mechanisms in a variety of different types of markets. One of the goals that these models seek to obtain is in predicting the future. Even though there is a strong support in academia for the relevance of the efficient market hypothesis, this doesnt imply that the people within these institutions are discouraged from attempting to do it. Conclusion It is possible to say that both agent-based and modern economic models have pros and cons. But, it isnt enough to leave it there. The simple fact is that both are seeking to find many of the same things, but in different ways. ACE models challenge the history of economic thought. And that in itself is something that professors of agent-based models have to face. But, concerning the efficient markets hypothesis, there needs to be a fresh perspective or another approach that attacks this from its blind side. The only way that there can be an improvement in modern economic understanding is if there is a sense of openmindedness within the economic

community, the will to try anything that is better. Its easiest to hold on to an understanding that has long been a part of ones life, but the true challenge is in opening your mind and entertaining other ideas that may actually lead you that much closer to the truth you seek.

References Foley, D., & Farmer, J.D. (2009). The Economy needs agent-based modelling. Nature, 460, 685686. Buchanan, M. (2009). Meltdown modelling. Nature, 460, 680-682. Tsang, E.P.K., & Martinez-Jaramillo, S. (2004, August). Computational finance. IEEE Computational Intelligence Society, 8-13. Farmer, J.D., & Lo, A.W. (Ed.). (1999). Frontiers of finance: evolution and efficient markets. Malkiel, B.G. (2003). The Efficient market hypothesis and its critics. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(1), 59-82. van den Bergh, W.M., Boer, K., de Bruin, A., Kaymak, U., & Spronk, J. (2002). On intelligentagent based analysis of financial markets. Working Paper, Erasmus University, Rotterdam. Tesfatsion, L. (2006, July 29). Introductory notes on financial markets. Retrieved from http://www.econ.iastate.edu/classes/econ308/tesfatsion/finintro.htm Tesfatsion, L. (2006, July 29). Information, bubbles, and the efficient markets hypothesis. Retrieved from http://www.econ.iastate.edu/classes/econ308/tesfatsion/emarketh.htm

También podría gustarte

- The Capital Markets and Market Efficiency: EightnineDocumento9 páginasThe Capital Markets and Market Efficiency: EightnineAnika VarkeyAún no hay calificaciones

- Article (EFM and Its Critics) 2003 CFADocumento2 páginasArticle (EFM and Its Critics) 2003 CFASheraz KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Literature Review On Stock Market EfficiencyDocumento4 páginasLiterature Review On Stock Market Efficiencyafmzslnxmqrjom100% (1)

- Capital Ideas Revisited - Part 2 - Thoughts On Beating A Mostly-Efficient Stock MarketDocumento11 páginasCapital Ideas Revisited - Part 2 - Thoughts On Beating A Mostly-Efficient Stock Marketpjs15Aún no hay calificaciones

- 17-Revisiting Market Efficiency - The Stock Market As A Complex Adaptive SystemDocumento9 páginas17-Revisiting Market Efficiency - The Stock Market As A Complex Adaptive SystemSjasmnAún no hay calificaciones

- Practical Investment Management 4Th Edition Strong Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocumento28 páginasPractical Investment Management 4Th Edition Strong Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFAdrianLynchpdci100% (8)

- Asset Pricing FullDocumento26 páginasAsset Pricing FullBhupendra RaiAún no hay calificaciones

- Reading 1 - Burghardt2011 - Chapter - RelatedTheoreticalAndEmpiricalDocumento25 páginasReading 1 - Burghardt2011 - Chapter - RelatedTheoreticalAndEmpiricalMeiliaAún no hay calificaciones

- Analytical Essay Efficient Market HypothesisDocumento6 páginasAnalytical Essay Efficient Market Hypothesistiffanyyounglittlerock100% (2)

- Chap 8 Lecture NoteDocumento4 páginasChap 8 Lecture NoteCloudSpireAún no hay calificaciones

- Asset Pricing ModelDocumento23 páginasAsset Pricing ModelNirati AroraAún no hay calificaciones

- Financial StatementDocumento4 páginasFinancial StatementVictoriaHuangAún no hay calificaciones

- Asset PortfolioDocumento3 páginasAsset PortfolioAhmed WaqasAún no hay calificaciones

- (London School of Commerce) : M.B.A (Ii) (Finance) Assingment: Investment Management and Capital Markets Critical ReviewDocumento12 páginas(London School of Commerce) : M.B.A (Ii) (Finance) Assingment: Investment Management and Capital Markets Critical ReviewNikunj PatelAún no hay calificaciones

- 463-Article Text-463-1-10-20160308Documento10 páginas463-Article Text-463-1-10-20160308Luciene MariaAún no hay calificaciones

- CHAPTER 5 Market Efficiency and TradingDocumento23 páginasCHAPTER 5 Market Efficiency and TradingLasborn DubeAún no hay calificaciones

- Efficient Market TheoryDocumento6 páginasEfficient Market TheoryRahul BisenAún no hay calificaciones

- Student Research Project: Prepared byDocumento31 páginasStudent Research Project: Prepared byPuneet SinghAún no hay calificaciones

- SWM EMH Evidence Oct 09Documento2 páginasSWM EMH Evidence Oct 09pasudlowAún no hay calificaciones

- The Predictive Power of Price PatternsDocumento25 páginasThe Predictive Power of Price PatternsGuyEyeAún no hay calificaciones

- Alphanomics by Charles LeeDocumento103 páginasAlphanomics by Charles LeeLuiz SobrinhoAún no hay calificaciones

- Portfolio & Investment Analysis Efficient-Market HypothesisDocumento137 páginasPortfolio & Investment Analysis Efficient-Market HypothesisVicky GoweAún no hay calificaciones

- Pairs Trading G GRDocumento31 páginasPairs Trading G GRSrinu BonuAún no hay calificaciones

- Market Efficiency ExplainedDocumento8 páginasMarket Efficiency ExplainedJay100% (1)

- Dissertation Topics On Efficient Market HypothesisDocumento8 páginasDissertation Topics On Efficient Market HypothesisHelpWithWritingAPaperCanada100% (1)

- Mauboussin - Capital Ideas Revisted pt2 PDFDocumento12 páginasMauboussin - Capital Ideas Revisted pt2 PDFRob72081Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Ascent of Market Efficiency: Finance That Cannot Be ProvenDe EverandThe Ascent of Market Efficiency: Finance That Cannot Be ProvenAún no hay calificaciones

- Literature Review Efficient Market HypothesisDocumento4 páginasLiterature Review Efficient Market Hypothesiserinadamslittlerock100% (1)

- Anomalies and The Efficient Markets HypothesisDocumento2 páginasAnomalies and The Efficient Markets HypothesisHaris ChaudhryAún no hay calificaciones

- ACM TOIS - Textual Analysis of Stock Market Prediction Using Financial News ArticlesDocumento29 páginasACM TOIS - Textual Analysis of Stock Market Prediction Using Financial News ArticlesAndanKusukaAún no hay calificaciones

- Efficient Market HypothesisDocumento3 páginasEfficient Market Hypothesismeetwithsanjay100% (1)

- The Beta Mystery - Are Investors Misled?: Roger M. ShelorDocumento6 páginasThe Beta Mystery - Are Investors Misled?: Roger M. ShelorYuwanTaraAún no hay calificaciones

- Info 9the Great Divide Over Market Efficiency 1Documento19 páginasInfo 9the Great Divide Over Market Efficiency 1Baddam Goutham ReddyAún no hay calificaciones

- The Efficient Markets HypothesisDocumento4 páginasThe Efficient Markets HypothesisTran Ha LinhAún no hay calificaciones

- Historical Background: Louis BachelierDocumento6 páginasHistorical Background: Louis BachelierchunchunroyAún no hay calificaciones

- Tseng - Behavioral Finance, Bounded Rationality, Traditional FinanceDocumento12 páginasTseng - Behavioral Finance, Bounded Rationality, Traditional FinanceMohsin YounisAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 5Documento14 páginasChapter 5elnathan azenawAún no hay calificaciones

- A Primer On Quick-Pick Momentum AccekeratorDocumento7 páginasA Primer On Quick-Pick Momentum AccekeratorIancu JianuAún no hay calificaciones

- Efficient Market HypothesisDocumento3 páginasEfficient Market HypothesisShameem AnwarAún no hay calificaciones

- Daniel Geto Article ReviewDocumento14 páginasDaniel Geto Article ReviewTikeher DemenaAún no hay calificaciones

- Investor Sentiment in The Stock Market: Malcolm Baker and Jeffrey WurglerDocumento23 páginasInvestor Sentiment in The Stock Market: Malcolm Baker and Jeffrey WurglerblablaAún no hay calificaciones

- Stock+market+returns+predictability ChaoDocumento31 páginasStock+market+returns+predictability Chaoalexa_sherpyAún no hay calificaciones

- Dissertation Stock Market EfficiencyDocumento7 páginasDissertation Stock Market EfficiencyWebsiteThatWritesPapersForYouSiouxFalls100% (1)

- AJMSE Vol23 No7 Dec2021-23Documento8 páginasAJMSE Vol23 No7 Dec2021-23lkwintelAún no hay calificaciones

- Frontiers of Finance: Evolution and Efficient MarketsDocumento2 páginasFrontiers of Finance: Evolution and Efficient MarketsRicardo BorriqueroAún no hay calificaciones

- Forecasting VolatilityDocumento132 páginasForecasting VolatilityPeter Pank100% (1)

- Efficient Market HypothesisDocumento8 páginasEfficient Market HypothesisGaara165100% (1)

- A Test of Market Efficiency Based On Share Repurchase AnnouncementsDocumento13 páginasA Test of Market Efficiency Based On Share Repurchase AnnouncementsiisteAún no hay calificaciones

- X-CAPM: An Extrapolative Capital Asset Pricing ModelDocumento61 páginasX-CAPM: An Extrapolative Capital Asset Pricing ModelPhuong NinhAún no hay calificaciones

- Efficient MArket Hypothesis and ForecastingDocumento13 páginasEfficient MArket Hypothesis and ForecastingDalia Hussniey AqeelAún no hay calificaciones

- The Efficient Market Theory and Evidence - Implications For Active Investment ManagementDocumento7 páginasThe Efficient Market Theory and Evidence - Implications For Active Investment ManagementDong SongAún no hay calificaciones

- Efficient Market Hypothesis: Weak-Form EfficiencyDocumento2 páginasEfficient Market Hypothesis: Weak-Form EfficiencyAbdullah ShahAún no hay calificaciones

- Price Dynamics in Financial Markets: A Kinetic Approach: ArticlesDocumento6 páginasPrice Dynamics in Financial Markets: A Kinetic Approach: ArticlesLolo SetAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 5: Sources of FundsDocumento14 páginasChapter 5: Sources of FundsVivien Joan AnastasiaAún no hay calificaciones

- Beat The MarketDocumento13 páginasBeat The Marketquantext100% (3)

- Price and Value: A Guide to Equity Market Valuation MetricsDe EverandPrice and Value: A Guide to Equity Market Valuation MetricsAún no hay calificaciones

- Joshua M. Carpenter: 38195 Price Road (513) 889-6972Documento2 páginasJoshua M. Carpenter: 38195 Price Road (513) 889-6972Josh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- Iraq Trip Statement of PurposeDocumento2 páginasIraq Trip Statement of PurposeJosh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- Construction ResumeDocumento2 páginasConstruction ResumeJosh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- Joshua M. Carpenter: 38195 Price Road (513) 889-6972Documento2 páginasJoshua M. Carpenter: 38195 Price Road (513) 889-6972Josh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- Short Essay On The ReformationDocumento12 páginasShort Essay On The ReformationJosh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- Anselms Ontological ArgumentDocumento1 páginaAnselms Ontological ArgumentJosh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- Economic Activity and McDonalds' StockDocumento8 páginasEconomic Activity and McDonalds' StockJosh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- Rockwell International B-1 BomberDocumento8 páginasRockwell International B-1 BomberJosh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- Wealth and Giving in The Bible: A Concise SummaryDocumento4 páginasWealth and Giving in The Bible: A Concise SummaryJosh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- Computable Economics: Challenge #3Documento7 páginasComputable Economics: Challenge #3Josh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- The Gathering: 09-10-2011Documento1 páginaThe Gathering: 09-10-2011Josh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- Millville Avenue Church of The Nazarene June NewsletterDocumento7 páginasMillville Avenue Church of The Nazarene June NewsletterJosh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- Sowing Seeds For The HarvestDocumento2 páginasSowing Seeds For The HarvestJosh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- Westboro Baptist Church Protest at Spc. Robert Hartwick FuneralDocumento1 páginaWestboro Baptist Church Protest at Spc. Robert Hartwick FuneralJosh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- PT Spring 11Documento4 páginasPT Spring 11Josh CarpenterAún no hay calificaciones

- RH-A Catalog PDFDocumento1 páginaRH-A Catalog PDFAchmad KAún no hay calificaciones

- Aditya Academy Syllabus-II 2020Documento7 páginasAditya Academy Syllabus-II 2020Tarun MajumdarAún no hay calificaciones

- Tribes Without RulersDocumento25 páginasTribes Without Rulersgulistan.alpaslan8134100% (1)

- Quality Standards For ECCE INDIA PDFDocumento41 páginasQuality Standards For ECCE INDIA PDFMaryam Ben100% (4)

- Ilovepdf MergedDocumento503 páginasIlovepdf MergedHemantAún no hay calificaciones

- Puma PypDocumento20 páginasPuma PypPrashanshaBahetiAún no hay calificaciones

- Object Oriented ParadigmDocumento2 páginasObject Oriented ParadigmDickson JohnAún no hay calificaciones

- Service Quality Dimensions of A Philippine State UDocumento10 páginasService Quality Dimensions of A Philippine State UVilma SottoAún no hay calificaciones

- Construction Project - Life Cycle PhasesDocumento4 páginasConstruction Project - Life Cycle Phasesaymanmomani2111Aún no hay calificaciones

- Meta100 AP Brochure WebDocumento15 páginasMeta100 AP Brochure WebFirman RamdhaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Swelab Alfa Plus User Manual V12Documento100 páginasSwelab Alfa Plus User Manual V12ERICKAún no hay calificaciones

- Sensitivity of Rapid Diagnostic Test and Microscopy in Malaria Diagnosis in Iva-Valley Suburb, EnuguDocumento4 páginasSensitivity of Rapid Diagnostic Test and Microscopy in Malaria Diagnosis in Iva-Valley Suburb, EnuguSMA N 1 TOROHAún no hay calificaciones

- Atoma Amd Mol&Us CCTK) : 2Nd ErmDocumento4 páginasAtoma Amd Mol&Us CCTK) : 2Nd ErmjanviAún no hay calificaciones

- Dog & Kitten: XshaperDocumento17 páginasDog & Kitten: XshaperAll PrintAún no hay calificaciones

- The Essence of Technology Is by No Means Anything TechnologicalDocumento22 páginasThe Essence of Technology Is by No Means Anything TechnologicalJerstine Airah SumadsadAún no hay calificaciones

- Spectroscopic Methods For Determination of DexketoprofenDocumento8 páginasSpectroscopic Methods For Determination of DexketoprofenManuel VanegasAún no hay calificaciones

- Passage To Abstract Mathematics 1st Edition Watkins Solutions ManualDocumento25 páginasPassage To Abstract Mathematics 1st Edition Watkins Solutions ManualMichaelWilliamscnot100% (50)

- Course Outline ENTR401 - Second Sem 2022 - 2023Documento6 páginasCourse Outline ENTR401 - Second Sem 2022 - 2023mahdi khunaiziAún no hay calificaciones

- Topic One ProcurementDocumento35 páginasTopic One ProcurementSaid Sabri KibwanaAún no hay calificaciones

- EPW, Vol.58, Issue No.44, 04 Nov 2023Documento66 páginasEPW, Vol.58, Issue No.44, 04 Nov 2023akashupscmadeeaseAún no hay calificaciones

- A Short Survey On Memory Based RLDocumento18 páginasA Short Survey On Memory Based RLcnt dvsAún no hay calificaciones

- Sim Uge1Documento62 páginasSim Uge1ALLIAH NICHOLE SEPADAAún no hay calificaciones

- Data SheetDocumento56 páginasData SheetfaycelAún no hay calificaciones

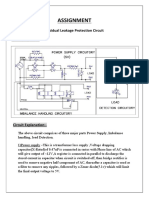

- Assignment: Residual Leakage Protection Circuit Circuit DiagramDocumento2 páginasAssignment: Residual Leakage Protection Circuit Circuit DiagramShivam ShrivastavaAún no hay calificaciones

- RSW - F - 01 " ": Building UtilitiesDocumento4 páginasRSW - F - 01 " ": Building Utilities62296bucoAún no hay calificaciones

- Department of Ece, Adhiparasakthi College of Engineering, KalavaiDocumento31 páginasDepartment of Ece, Adhiparasakthi College of Engineering, KalavaiGiri PrasadAún no hay calificaciones

- CHAPTER 2 Part2 csc159Documento26 páginasCHAPTER 2 Part2 csc159Wan Syazwan ImanAún no hay calificaciones

- MLX90614Documento44 páginasMLX90614ehsan1985Aún no hay calificaciones

- Plan Lectie Clasa 5 D HaineDocumento5 páginasPlan Lectie Clasa 5 D HaineCristina GrapinoiuAún no hay calificaciones

- P3 Past Papers Model AnswersDocumento211 páginasP3 Past Papers Model AnswersEyad UsamaAún no hay calificaciones