Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Narrative Inquiry Conf Paper - Harmonising The Voices

Cargado por

Dianne AllenTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Narrative Inquiry Conf Paper - Harmonising The Voices

Cargado por

Dianne AllenCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry,

University of Wollongong

Harmonising the voices: narrative, inquiry and professional practice

Meeta Chatterjee, Dianne Allen and Heather Jamieson Learning Development, and Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong

April, 2008

Contents

Harmonising the voices: narrative, inquiry and professional practice ........................... 1 Abstract .......................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 2 Context ........................................................................................................................... 3 The different perspectives that inform our practice ....................................................... 4 Diannes Voice The Markers Perspective ................................................................. 5 Learning Development perspective ............................................................................... 7 Heathers voice our teaching approach ................................................................... 8 Meetas voice consideration of the issue of Voice ................................................. 9 What stimulated me to investigate this .............................................................. 9 My research story ............................................................................................ 10 A coda .. of sorts .................................................................................................. 13 Drawing towards a tentative conclusion: ..................................................................... 14 How has participating in this narrative inquiry forum helped inform our teaching/ marking in this subject? (Our 3 voices) .................................................................. 14 Bibliography ................................................................................................................ 15 APPENDIX .................................................................................................................. 17 PRESENTATION: ....................................................................................................... 18

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

Abstract

This paper explores the experience of teaching students to use narrative and inquiry as a way of reflecting on and improving professional practice. During their course of study the students are required to engage with and subsequently draw together different sources of information and disparate forms of expression expert opinion in the highly resolved language of published research, interview and other empirical data, usually expressed in spoken language, and the students own reflections on their professional and personal experience. Because impersonality and objectivity are often perceived as the key characteristics of academic writing, it is a challenging process for many students to weave these voices together into a personally inflected research story. This paper reflects on the process of helping students to negotiate the component genres and sources of information and deploy them in their written tasks. It is presented from two perspectives. The first is that of the marker who has been in the unique position of observing the progress of students from the initial stages of formulating a question, through the intervening period of answering the question using the different sources of information and finally to displaying the qualities of a reflexive practitioner. The second perspective is that of the learning development lecturers who have provided formative writing activities to scaffold and make explicit the writing processes involved and subsequently help the students wrestle the material into a harmonious whole. Keywords: narrative, inquiry, self-study, voice

Introduction

One aspect of masters studies in many Australian course designs involves introducing students to the practice of research, to know its boundaries and strengths and to be able to critically engage with the reported research findings of others. EDGZ921, Introduction to Research and Inquiry, a six credit point unit of study in the Master of Education within various specialities at the University of Wollongong, is not different from other courses in these objectives. It does, however, appear to be different in the way it addresses these objectives. EDGZ921 seeks to introduce and teach these objectives by asking students to use narrative and inquiry as a way of reflecting on and improving professional practice.

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

Students are required to engage with and subsequently draw together different sources of information and disparate forms of expression expert opinion in the highly resolved language of published research, interview and other empirical data, usually expressed in spoken language, and the students own reflections on their professional and personal experience. Because impersonality and objectivity are often perceived as the key characteristics of academic writing, it is a challenging process for many students to weave these voices together into a personally inflected research story.

As teachers we are relatively new to the task of providing support in this course: marking assignments and giving formative as well as summative feedback, and conducting process support in the area of the functional literacies required to undertake the tasks associated with this unit of study. In this paper we commence the process of reflecting on what is involved in helping students to negotiate the component genres and sources of information and deploy them in their written tasks. Our observations reflect the different backgrounds we bring to the task, related to the understandings we have of what the support role asks of us. Consequently our paper is presented from two main perspectives. The first is that of the marker who has been in the unique position of observing the progress of students from the initial stages of formulating a question, through the intervening period of answering the question using the different sources of information and finally to displaying the qualities of a reflexive practitioner. The second perspective is that of the learning development lecturers who have provided formative writing activities to scaffold and make explicit the writing processes involved and subsequently help the students wrestle the material into a harmonious whole. Our overriding objective is finding out how we can assist our students with their learning tasks in this subject. Our focus in this paper is the use of voice in the process of writing a narrative and reporting an inquiry arising out of that narrative.

Context

The unit Introduction to Research and Inquiry (EDGZ921) is a compulsory component of coursework study at masters level in the Faculty of Education at Wollongong University, and part of preparatory studies for research degrees for

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

cohorts which include a significant number of international students. As presently constructed, it is a one-semester course (12-14 weeks) which involves the writing up, examination and sharing of a story, developed from a recount of something significant from the students practice experience which poses a problem. The identified problem is investigated, drawing on the literature of published research, further personal reflective work and the collection of data from others practice experience, e.g. by interview. This built into a research story. (For further detail see Allen, 2008 later in these conference proceedings.)

The course has four major assessment strands: (1) Problem Posing Vignette (PPV) 1,000 word recount of a particular teaching event or an area of professional learning that the student wishes to explore, leading to focus questions to guide subsequent research; (2) Research Story - 4,000 word document drawing on the students reflective journal, literature review, empirical study; (3) Critical response - 1,000 word reflexive dialogue with a critical friend; (4) Hurdle - 10 short online posts.

The different perspectives that inform our practice

As support staff for the course, we have had a number of interactions over the Spring semester and since, seeking to understand where we are each coming from and how, together, we can provide feedback that harmonises, and moves towards helping students get the best outcomes possible from the unit of study. We come to our respective tasks from different backgrounds and have been immersed in different conceptual frames. Diannes most recent work has been within the arena of reflective practice (Donald Schon, John Dewey and others working from these bases). Heather and Meetas approach to the teaching of English language and literacy is oriented toward language as social practice, and is informed by systemic functional linguistics and critical discourse analysis. Meetas experience includes cross-cultural elements and significant engagement in TESOL and writing. But we all acknowledge that we too are still learning.

One of our reflexive engagements with this paper involves finding out (learning-bydoing) if we can harmonise our voices as well as the voices of the data and

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

literature. One pointer in this endeavour is John Herons concept of isomorphism as collaborative inquirers, from different perspectives, seek to draw their perceptions together, the finding of commonality may mark (as in triangulation) some significant overlap of basic principles with other, related fields of knowledge, and approach somewhat closer to a trueness about the phenomenon examined (Heron, 1992).

Diannes Voice The Markers Perspective

I come to the marking of the assessment tasks of this subject with a clear view that the practice story, the narrative, is a key element of recognising and tapping practice knowledge, and with the objective of endeavouring to contribute to professional development for these masters students by providing formative feedback in the development of practice-relevant research and its reporting. (For further detail see Allen, 2008, later in the conference proceedings; see also Allen, 2005 thesis.)

My inputs, and associated thinking, were captured in contemporaneous reflective notes that helped me keep track of what was I assessing, how, and why; what were my concerns in marking (consistency; assessment appropriate to curriculum intent; being appreciative; providing useful formative feedback); what was I noticing about process and students responses and difficulties in order to give general advice; and how was I expressing feedback that I thought relevant (some of this contributes to my own learning about writing, and about the research process). From these notes I compiled contemporaneous general assignment reports for the students, the Subject Lecturer and the Learning Development team for the three assessment tasks. I also engaged in end-of-course evaluation with the Subject Lecturer and Learning Development team. In the course of marking I compiled digital copies of the students work and my feedback, and in continuing the how do I improve ..? conversation with the Learning Development team I have come to appreciate more what are some of the issues involved in reporting on practice-relevant inquiry, and via the self-study approach.

As I marked, three key aspects of the whole process have become apparent. Firstly, ownership of research impacts on quality. Students are engaged with their particular question and there are implications of, and practical evaluation criteria being applied to, the work being done. Secondly, voice is a key aspect of success in the task, and

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

holding on to first person voice and self-study examination while reporting to peers is difficult. A third observation is that discussion with a critical friend, once the Research Story is finalised, is an important and rewarding experience, and students get feedback that good narrative written style is appreciated by the reader it has communicative power.

In providing general feedback to the PPV task, I enunciate the following indications of good for the three basic components of the task:

(a) A 'good' reflection on past experience/ current practice moves from description to evaluation, touching on how the practitioner is prioritising amongst the multiple evaluations possible. If it identifies a dilemma, competition between values, it is on the way to identifying a problem that will need to be researched, and thought about, to reconsider assumptions, previous actions, previous conclusions, and/or previous motivations, with a view to perhaps changing, or knowing more of why this is a dilemma for you, and may always be a dilemma for you (b) 'Good' 'thick, rich description', for me, allows the reader (me) to make relatable connections, to recognize their own practice/practice dilemmas in the contextual information provided (c) A 'good' Focus Question will be clear and researchable. For self-study, the "I" focus helps clarify, by moving from the 'instrumental/ scientific/ objective/ generalisable' to the personal change component, recognizing self as significant, and recognizing the specific context as significant.

(General Feedback to Assignment 1 EDGZ921 Autumn 2007) One of the key inputs that I make, in providing feedback to the PPV, is to recommend that students endeavour to cast one of their focus questions in I terms. The intent is to help them shift from a practical-technical frame to a self-study frame. As I have looked at the Research Stories in Spring 2007, attending to voice and quality of report and learning, the observation of how difficult it is to hold on to the first person voice and self-study examination, while reporting to peers, also flags a significant problem for my ongoing practice as marker. Just under half the students, who were able to express one of their focus questions in I terms, were not able to progress the rest of the way into reporting findings related to self-study in their final report. How do I help these students? Are there insights from the perspectives of Learning Development that help me understand what I am trying to do and how?

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

Learning Development perspective

In Spring 2007, negotiation between the EDGZ921 subject lecturer and Wollongong Universitys Learning Development unit at resulted in a decision that Learning Development staff would provide integrated learning support during class time. This decision to increase the involvement of Learning Development was because of the priority areas of learning support that the subject and its students represent: EDGZ921 is an introductory subject where students are making a transition to new forms of inquiry, and it has a high proportion of international students who are relative newcomers to the educational context of the Australian university and/or English as the language of instruction.

The identification of these areas as priorities for learning support is a reflection of the academic literacies approach that guides Learning Development practice at the University of Wollongong (see for example Lea and Street, 1998; Hoadley-Maidment, 2000). Academic literacies (AL) is a developmental rather than a remedial approach to student learning, proceeding on the idea that all students need to negotiate new genres, text types, forms of inquiry, and epistemologies. By attempting to articulate the complexity and diversity of literacy practices in the contemporary academy, AL seeks to go beyond a deficit model of learning support, which is associated with an academic skills approach, as well as to problematise the depiction of academic culture as homogenous, a limitation of an academic socialisation approach. Learning Developments actual contribution to the in-class teaching in EDGZ921 in Spring 2007 was in the form of four tutorials which focused on assessment related tasks: (1) writing a professional journal, writing a problem posing vignette (PPV); (2) writing a literature review, undertaking critical analysis, considering the nature of evidence and voice; (3) framing interview questions, writing up interview data; (4) writing the research story, integrating the evidence, writing a cohesive extended text. The teaching strategies adopted in these tutorials included explicit focus on the assessment criteria, annotated models of text types and genres, and reiteration of task types to allow development of skills. In addition, the students had individual

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

consultations with the Learning Development lecturers who provided detailed comments on draft versions of written assessments.

Heathers voice our teaching approach

My perspective is that of a relative newcomer to narrative inquiry, and my interest is in whether trying to identify what is distinctive about its epistemological framework might illuminate and inform our teaching in subjects where a narrative inquiry mode is adopted.

The AL approach that guides our teaching has undoubted advantages. One of its strengths is its articulation of the diversity and complexity of literacies in the contemporary academy. This provides a useful framework for considering the array of literacy practices required of the students in a subject like EDGZ921. Relevantly, the AL approach recognises literacies as social practices in which epistemology and identity are inherent components, and it identifies that a variety of communicative repertoires operate in the academy, requiring students to negotiate conflicting literacy practices and develop a capacity for modulation of their own linguistic practices (Lea and Street, 1998, 172). However, I have some reservations about it, or at least feel that we need to reflect on the way in which we deploy it in our teaching strategies. There is a tension between conceptualising complexity and pedagogic practice, for example scaffolding the students negotiation of writing tasks.

From our interactions with students in EDGZ921, especially in individual writing consultations, we observe that their biggest problems relate to orchestrating the various sources of information: (1) integrating the different forms of evidence; (2) honouring their own experiences; (3) placing their voices against those of others, especially relating the scholarly literature to own experience; and (4) handling the voices from their data. These difficulties indicate that the students need more help in negotiating the shift in approach to knowledge and voice that this subject requires. One of the teaching strategies we use is providing annotated examples of good and bad texts. For this we try to use authentic samples of writing, which has some

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

distinct advantages but also the disadvantage of making it difficult to isolate what is good (or bad) from other features of the text. In particular it seems that the shift in voice and epistemology that needed in this context is hard to model grammatically or textually. As both Dianne and Meeta point out, this is not a simple matter of using first person singular pronoun, though it seems to help a bit. My questions are how can I better conceptualise the difference between the textual I and the epistemological I, and how can I translate this into an AL teaching framework. A good starting point is a better engagement with the elusive concept of voice, as in Meetas exploration below.

Meetas voice consideration of the issue of Voice

What stimulated me to investigate this

Can I actually write I and me in my Problem Solving Vignette? I find this very confusing. When I was doing my English language course at the college, if I wrote I or me in my essay, my teacher would write in the margin, You cannot use I or me in academic writing. Academic writing is impersonal. Your opinions and feelings are not important..

I took a deep breath as I thought of an acceptable answer. I realised that as an academic skills teacher, I have given similar feedback to students in other subjects. However, this subject was different. As an introduction to a research method that involves self-study, not only was I acceptable but central to the method of inquiry. Narrative inquiry is a relatively new research interest for me. The form of inquiry is intriguing because of its emphasis on research being communicated with the directness and simplicity of story telling. Combined with the fact that the research method aims at developing professional reflexivity, the assessments in the subject not only encourage lifting the embargo on I and me, but make space for an active engagement of the self in practice through using relevant literature, empirical research and finally ones own reflection on the topic. My response to Hiroshis question (quoted above) ultimately was a discussion on how the writing of an essay differs from the writing required in the subject. We spoke

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

10

about the differences in the purpose of writing the texts; the approach to knowledge that underlies both kinds of writing; and the language used. This is partly what we uncovered: Essay conventions Purpose of the essay: Generally to advance an argument: A claim wellsupported by relevant and convincing evidence. EDGZ921 writing expectations in the PPV and the research story Purpose of a PPV: To recount and describe a teaching/learning experience with a view to explore an area of concern so as to improve practice Purpose of a research story: To narrate the experience of exploration using literature reviews, empirical research, ones own reflection and a critical friend. Subjective experience validated and valued. Exploration of professional practice through the filter of personal experience of great importance. Personal voice, I embraced. Inclusion of the active voice wherever necessary. Coherence achieved by using established criteria in a narrative eg. Temporal/ chronological/ thematic or causal connection Type of evidence: Emphasis on feelings, observation and reflection noticing in the PPV and in the research story, voices from scholars, research participant/s, own journal, critical friend

Approach to knowledge: Located outside the writer and displayed Objectively Language: Impersonal language: I erased grammatically through the use of passive and nominalised forms Coherence achieved through presenting: A claim well-supported by relevant and convincing evidence Type of evidence: Privileging evidence from established scholarly sources

In the Problem Posing Vignette (PPV) the text type expected involves making the personal experience paramount. Thus the problem that Hiroshi raised was not restricted to the use of the personal pronouns. It had to do with a larger issue of identity in writing.

My research story

The first step of the journey, for me, involved putting myself through the process. I examined the literature on identity and voice, talked to students about their experiences (an excerpt is presented above) and reflected on the findings to inform my pedagogy. What follows is a brief recount of that journey.

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

11

Identity in academic writing has been the focus of many empirical and theoretical studies. The notion of identity has shaped and encouraged heated discussions on the elusive concept of voice especially with regard to second language (L2) writing. Three of them will be briefly overviewed here.

Hyland (2002) explores the use of first person pronouns in 64 Hong Kong undergraduate theses written by L2 writers and compares them with a large corpus of research articles and finds that significant underuse of authorial references realised through the personal pronouns. In interviews with students and supervisors, Hyland observed that two things become obvious. Firstly, students tended to follow the recommendations of style guides and teaching programs that advocate objectivity and anonymity. Secondly, even if student writers were aware of the rhetorical potential of I, they may be inclined to avoid personal responsibility and the notion of authority that goes with the projection of I in an academic text.

Another interesting study by Tang and John (1999) based on 27 undergraduate essays builds a useful typology. The typology is presented below.

No I I as I as representative guide eg. we the French know I as architect I as raconteur of research process eg. the data I collected I as opinionmaker eg. I think that Khushwant Singh has I as originator

Least powerful authorial presence

Most powerful authorial presence

On the basis of their studies, the authors argue that issues of writer identity deserve to be discussed so that students can confidently make decisions about the identity they might want to present in their texts. Effective writing education programs, they suggest, need to encourage students to critically use personal pronouns to create the meaning they want to create. However, individualistic identity implied in the use of I can be problematic for many L2 writers because, as Scollon (1994) points out, Asian students may be reluctant to assume a great deal of textual authority since it

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

12

may be construed as too powerful by the reader who is used to a more collectively construed identity. Perhaps, one of the most influential studies on identity is Ivanics (1998) book length work that reports on her research with eight mature co-researchers. The study aims at uncovering what toolkits are brought into the practice of writing by different groups of writers. She theorizes that in writing four aspects of the writers self exist in texts in some form or the other. These are: the autobiographical self that relates the writer as the performer. This encompasses the socially constructed self that is a hold-all term used to cover dimensions of gender, ethnicity, age etc., and it is not a fixed self, but constantly evolves in response to the contexts and situations that surround one. the discoursal self is concerned with the writer as character in their text. It could refer to the problematic way in which student writers portray themselves in their writing. This self may embody the values, beliefs and the power relations in their academic context, in other words, it contributes to an appropriate voice in writing. the authorial self that interacts with other texts (spoken/written tacitly said to exist in society), negotiates them and incorporates them in writing. Some academic writers, especially, in the beginning stages, tend to be self-effacing (Ivanic, 1998, 26) in their writing because they are still working out how to author texts, how much authority one is acceptable in ones academic writing. the fourth dimension of the self is concerned with the possibilities of selfhood. It refers to the abstract prototypical identities available in the socio-cultural context of writing (Ivanic, 1998, 23) or the affiliations that the writer may choose for themselves eg. environmentalist, gay activist and so on. Applying these off-the-peg combinations (Ivanic, 1998, 27) in a research context would mean choosing the label constructivist, or positivist, or critical theorist to define oneself. The literature is rich and varied in terms of its empirical and conceptual imaginings of identity. One of my problems was to link the insights gathered from the readings to the practicalities of a classroom situation.

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

13

Talking to students about their work was also an eye-opener. Their struggles to juggle the different voices in texts needed pedagogic attention. For example, in response to Hiroshis question about, How can I read so much and remember what is relevant? (Journal note, 5/8/07), a note-taking tool (see Appendix) was suggested. Annotated versions of PPVs were useful in showing the staging of texts. The notion of ones own voice is difficult to teach. In the next iteration of the course, I may use this text to deconstruct how my identity is constructed here.

A coda .. of sorts

My reading alerted me to a number of things. Above all, was the awareness that the insertion of I is not just a superficial grafting of personal pronoun to the text. As Ivanic (1998) argues, writing is not a neutral activity which we just learn like a physical skill, but it implicates every fibre of the writers multifaceted being (1998, 181). At the core of the very act of writing is the person who shapes the writing, making important choices, whether it is an essay or an assignment for EDGZ921. The EDGZ921 assignments called for a greater disclosure of the different selves characterised by Ivanics typology. The challenge will be to help student writers articulate a voice that represents those selves and the voices of others. How they orchestrate those various voices will depend on their own experiences and the directions that they want to take.

Perhaps, my job as a learning developer is to subtly contribute to the writing by engaging in dialogue to facilitate the acquisition of the self-assurance required to take on the varied roles of the guide, the architect of the text, raconteur of the research and the originator of the knowledge (Tang and John 1999). In practical terms, this would imply the development of a toolkit or in Ivanics words, an array of mediational means (1998, 52) that would help new researchers construct an I for the subject in their texts.

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

14

Drawing towards a tentative conclusion:

How has participating in this narrative inquiry forum helped inform our teaching/ marking in this subject? (Our 3 voices)

This examination of our practice, recognising our different emphases and voices, has been designed to help us explore what we have learned from our first round experience and in what ways we might feed back that learning into the course and our ongoing responsibilities in providing support to the students undertaking the course. Here we are reporting some of our tentative conclusions (King & Kitchener, 1994) as we proceed into further rounds of practice. The Learning Development teams teaching approach is informed by an academic literacies model, arguably the best out of study skills and socialisation. But is our model, which may or may not do justice to the comprehensiveness of academic literacies, and/or the most effective way of teaching this kind of literacy? What the teaching involves is the use of good and bad examples with annotations, which attempt to make explicit what the criteria are for good and bad. But does this sort of commentary at a grammatical level really get at the epistemological stance thats required? One of our appreciations, from a good example, is that the writing is as a whole and with a structure that is quite complex. Annotating what is good, from good writing, is difficult. Another of our appreciations is that bringing the I voice into the reporting of inquiry is not a simple task. Being aware of the different kinds of personal voice, as for example spoken of in Elijahs, Tang & Johns and Ivanics work helps us to be more alert about what the task of helping our students negotiate EDGZ921, successfully, involves, and how that might provide key instruction for any further ongoing inquiries these students conduct as practising professionals.

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

15

This exercise of collaborative reflection, and in the context of a joint construction for presentation and publication, has taken us some way into the journey that Schon speaks of in progressing from personal experience to validated knowledge. Schon points out that the reflective work that starts out in the individual needs to be put through a process of testing, by dialogue, in a socially supportive environment where there is affirm[ing] without dogmatism and confront[ing] without hostility [(Hainer,1968)] (Schon, 1991). We have found it truly instructive, and in ways that individual effort could not have accomplished.

Bibliography

Allen, D., 2005, Contributing to Learning to Change: Developing an action learning peer support group of professionals to investigate ways of improving their own professional practice. Unpublished M.Ed.(Hons), University of Wollongong, Wollongong. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/288/ Elijah, R., 2004, Voice in Self-Study. In J. J. Loughran & M. L. Hamilton & V. K. LaBoskey & T. Russell (Eds.), International Handbook of Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices (pp. 247-271). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Heron, J., 1992, Feeling and Personhood: Psychology in Another Key. London: Sage. Hoadley-Maidment, E., 2000. From Personal Experience to Reflective Practitioner: Academic Literacies and Professional Education. In M.R. Lea & B. Stierer (Eds.), Student Writing in Higher Education: New Contexts (pp. 165-178). Buckingham: Open University Press. Hyland, K., 2002, Authority and invisibility: authorial identity in academic writing, Journal of Pragmatics, Volume 34, 1091-1112 Ivanic, R. 1998, Writing and Identity: The Discoursal Construction of Identity in Academic Writing, Amsterdam: John Benjamins. King, P., & Kitchener, K., 1994, Developing Reflective Judgment: understanding and promoting intellectual growth and critical thinking in adolescents and adults. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Lea, M.R. and Street, B.V., 1998, Student Writing in Higher Education: an academic literacies approach, Studies in Higher Education, Vol. 23, 2, 157-172. Schon, D. A. (Ed.). 1991. The Reflective Turn: Case Studies in and on educational practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

16

Scollon, R., 1994, As a matter of fact: The changing ideology of authorship and responsibility in discourse, World Englishes, 13, 33-46 Tang, R., and John, S., 1999, The I in identity: Exploring writer identity in student academic writing through the first person pronoun, English For Specific Purposes, 18, S 23-S39.

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

17

APPENDIX

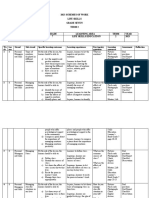

Note taking tool to include student writers voice Author Theoretical Research Research Year Framework Question/ Method Theme Issue/s Hyland, Ivanic, 1997 Is 240 K.,2002 academic published writing as journal uniformly articles objective 30 in 8 and disciplines impersonal p. 353 are as it is textually commonly analysed portrayed using to be? Wordpilot . Findings soft knowledge domains used more 1st person pronouns. Undergrads. used fewer pronouns than published texts- believing that I and we are inappropriate in academic writing My thoughts

A peer-review report on my contribution came back with a note that the used of first person is not acceptable in academic writing. Does the pronoun I indicate authority?

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

18

PRESENTATION:

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

19

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

20

Harmonising the voices: narrative inquiry and professional practice Paper delivered to 2008 Inaugural Conference on Narrative Inquiry, University of Wollongong

21

También podría gustarte

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2099)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Role Play in Training For Clinical Psychology Practice - Investing To Increase Educative OutcomesDocumento19 páginasRole Play in Training For Clinical Psychology Practice - Investing To Increase Educative OutcomesDianne Allen100% (3)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- Labor Relations: Labor Relations Are The Study and Practice of Managing Unionized EmploymentDocumento11 páginasLabor Relations: Labor Relations Are The Study and Practice of Managing Unionized EmploymentSubrata BasakAún no hay calificaciones

- Strengths of The Pluralist PerspectiveDocumento3 páginasStrengths of The Pluralist PerspectiveYashnaJugoo100% (1)

- Decision Making in The Administration of Public PolicyDocumento15 páginasDecision Making in The Administration of Public Policyاحمد صلاح100% (1)

- 04-Case Study On Air Products CorporationDocumento3 páginas04-Case Study On Air Products CorporationtirthanpAún no hay calificaciones

- Lake Illawarra ReportDocumento20 páginasLake Illawarra ReportDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Dispute Resolution: Industrial Dispute Resolution Issues, Trends and ImplicationsDocumento81 páginasDispute Resolution: Industrial Dispute Resolution Issues, Trends and ImplicationsDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Rejection: Jesus Has Been Hurt To Take in All of Your Hurts To HimselfDocumento3 páginasRejection: Jesus Has Been Hurt To Take in All of Your Hurts To HimselfDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Illawarra Region Report 1974Documento56 páginasIllawarra Region Report 1974Dianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Dispute Resolution: Lessons To Be Learned From The Experience of Disputes in The Construction IndustryDocumento63 páginasDispute Resolution: Lessons To Be Learned From The Experience of Disputes in The Construction IndustryDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Supervision of Clinical Psychology PracticeDocumento5 páginasSupervision of Clinical Psychology PracticeDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Scriptural View of Suffering 2007Documento4 páginasScriptural View of Suffering 2007Dianne Allen100% (1)

- Reflective InquiryDocumento15 páginasReflective InquiryDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Faulty Thinking Background and Self Awareness GridDocumento6 páginasFaulty Thinking Background and Self Awareness GridDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Using Psychological Type To Consider Learning Activity DesigningDocumento4 páginasUsing Psychological Type To Consider Learning Activity DesigningDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Dispute Resolution: Learning From The Experience of Disputes at Shell Harbour City CouncilDocumento92 páginasDispute Resolution: Learning From The Experience of Disputes at Shell Harbour City CouncilDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Educative Process - Design of EDUT 422 2004Documento2 páginasEducative Process - Design of EDUT 422 2004Dianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Learning Experience Design of EDUT 422 2002Documento1 páginaLearning Experience Design of EDUT 422 2002Dianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Considerations For Improving Supervision of Clinical Practice From An Exploratory Case StudyDocumento23 páginasConsiderations For Improving Supervision of Clinical Practice From An Exploratory Case StudyDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Narrative Inquiry Conf Paper - The Story and Working On Practice KnowledgeDocumento24 páginasNarrative Inquiry Conf Paper - The Story and Working On Practice KnowledgeDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Dispute Resolution: Equipping Staff To Handle Disputes Effectively in Local GovernmentDocumento111 páginasDispute Resolution: Equipping Staff To Handle Disputes Effectively in Local GovernmentDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Dispute Resolution: Facilitation - The Use of Mediation Techniques Processes in Resolving Differences in Group Decision-MakingDocumento99 páginasDispute Resolution: Facilitation - The Use of Mediation Techniques Processes in Resolving Differences in Group Decision-MakingDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Dispute Resolution: Resources For Strategic InterventionsDocumento38 páginasDispute Resolution: Resources For Strategic InterventionsDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- How Can I Use The Research ApproachesDocumento1 páginaHow Can I Use The Research ApproachesDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Dispute Resolution: Nature of Conflict & Its Role in SocietyDocumento139 páginasDispute Resolution: Nature of Conflict & Its Role in SocietyDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Dispute Resolution: Issues in Training in Negotiation Skills For An Organisational SettingDocumento61 páginasDispute Resolution: Issues in Training in Negotiation Skills For An Organisational SettingDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Adult Education: The Role of Language in Trans Formative Learning and Spiritual TraditionsDocumento11 páginasAdult Education: The Role of Language in Trans Formative Learning and Spiritual TraditionsDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Adult Education: Scaffolding For Adult Learners Working With Learning To ChangeDocumento10 páginasAdult Education: Scaffolding For Adult Learners Working With Learning To ChangeDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Adult Education: Learning Experience Design For The Development of A Richer Understanding of Reflective WorkDocumento14 páginasAdult Education: Learning Experience Design For The Development of A Richer Understanding of Reflective WorkDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Adult Education: Learning From DiscomfortDocumento14 páginasAdult Education: Learning From DiscomfortDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- MEd: Research Proposal: How To Introduce The Use of Reflective Techniques To Enhance Learning From Role-Plays, Simulations and Other Experiential Components of The Dispute Resolution Coursework.Documento9 páginasMEd: Research Proposal: How To Introduce The Use of Reflective Techniques To Enhance Learning From Role-Plays, Simulations and Other Experiential Components of The Dispute Resolution Coursework.Dianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- MEd: Argue Problem and MethodDocumento19 páginasMEd: Argue Problem and MethodDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- MEd: Design A Research StrategyDocumento14 páginasMEd: Design A Research StrategyDianne AllenAún no hay calificaciones

- Practice of Law For at Least Ten Years.' (Emphasis Supplied)Documento79 páginasPractice of Law For at Least Ten Years.' (Emphasis Supplied)Jannina Pinson RanceAún no hay calificaciones

- Lesson 5 - Cphn01cDocumento34 páginasLesson 5 - Cphn01cKaiAún no hay calificaciones

- Enter The Survival Horror - Core Rules - 0.5.4Documento49 páginasEnter The Survival Horror - Core Rules - 0.5.4Evandro FormozoAún no hay calificaciones

- A Practical Guide To DialogueDocumento30 páginasA Practical Guide To DialogueAlvaro Mellado DominguezAún no hay calificaciones

- Human Resourse Management Module 2 GCCDocumento27 páginasHuman Resourse Management Module 2 GCCManish YadavAún no hay calificaciones

- Industrial RelationsDocumento76 páginasIndustrial Relationstamilselvanusha100% (1)

- Catalogue 2016 UNDP CIPS Training and Certification 6 PDFDocumento1 páginaCatalogue 2016 UNDP CIPS Training and Certification 6 PDFHema Chandra IndlaAún no hay calificaciones

- Soft Skills Knc101 St-2 QPDocumento1 páginaSoft Skills Knc101 St-2 QPjaipalsinghmalik47Aún no hay calificaciones

- AFITD Module-Two NegotiationDocumento14 páginasAFITD Module-Two NegotiationAnonymous oVIEi4FxQyAún no hay calificaciones

- Trompenaars Cultural Dimensions ExplainedDocumento23 páginasTrompenaars Cultural Dimensions ExplainedkingshukbAún no hay calificaciones

- Miller HostageCrisisDocumento185 páginasMiller HostageCrisismars_migration100% (1)

- Integrative Approach Blemba 65Documento26 páginasIntegrative Approach Blemba 65Simon ErickAún no hay calificaciones

- Audu DiplomacyDocumento10 páginasAudu DiplomacyUseni AuduAún no hay calificaciones

- Negotiation NotesDocumento61 páginasNegotiation NotesS.S RayAún no hay calificaciones

- Seminar Strategic Contract Management For Oil GasDocumento13 páginasSeminar Strategic Contract Management For Oil Gaskhan4luvAún no hay calificaciones

- 2023 Grade 7 Mentor Life Skills Education Schemes of Work Term 1 13 22 Dec 08 51 17Documento7 páginas2023 Grade 7 Mentor Life Skills Education Schemes of Work Term 1 13 22 Dec 08 51 17SUEAún no hay calificaciones

- PreviewpdfDocumento45 páginasPreviewpdfSUSMITHAAún no hay calificaciones

- Work BookDocumento34 páginasWork BookRochak BhattaAún no hay calificaciones

- Doing Business with DARPADocumento15 páginasDoing Business with DARPAJAún no hay calificaciones

- ANC PEC StatementDocumento2 páginasANC PEC StatementeNCA.comAún no hay calificaciones

- Electronics/Semiconductor Machine Servicing QualificationDocumento121 páginasElectronics/Semiconductor Machine Servicing QualificationFrancis Rico Mutia RufonAún no hay calificaciones

- Essentials of Negotiation 6th Edition Lewicki Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocumento35 páginasEssentials of Negotiation 6th Edition Lewicki Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFChristopherRosefpzt100% (11)

- Assignment PDFDocumento9 páginasAssignment PDFTurban RiderAún no hay calificaciones

- 1Documento11 páginas1Divine PhoenixAún no hay calificaciones

- Licensing System in Norway: Norwegian Petroleum DirectorateDocumento22 páginasLicensing System in Norway: Norwegian Petroleum Directoraterutty7Aún no hay calificaciones

- Collective BargainingDocumento12 páginasCollective BargainingsreekalaAún no hay calificaciones