Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

A Conceptual and Empirical Comparison of Three Market Orientation Scales

Cargado por

Harris Adiyono PutraDescripción original:

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

A Conceptual and Empirical Comparison of Three Market Orientation Scales

Cargado por

Harris Adiyono PutraCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 1 8

A conceptual and empirical comparison of three market orientation scales

Ken Matsunoa,*, John T. Mentzerb, Joseph O. Rentzb

b

Marketing Division, Babson College, Babson Park, MA 02457-0310, USA Department of Marketing, Logistics, and Transportation, 310 Stokely Management Center, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996-0530, USA Received 3 October 2000; accepted 14 February 2003

Abstract Although the topic of a market orientation has attracted considerable research attention, there still is no clear consensus on its definition and on how to measure it. The authors attempt to improve market orientation conceptualization and measurement by conceptually and empirically comparing three different scales of market orientation, the scales of Kohli and Jaworski, Narver and Slater and a newly developed extended market orientation (EMO) scale. Implications of the results and a future research agenda are also offered. D 2003 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Market orientation; Scale comparison; Extended market orientation

1. Introduction Although market orientation has attracted considerable research interest (e.g., Jaworski and Kohli, 1993; Kohli et al., 1993; Narver and Slater, 1990; Slater and Narver, 1994), confusion still exists as to its definition, how to measure it (the construct of market orientation) and how it is developed (i.e., the antecedents to a market orientation). In this paper, our particular interest lies in the conceptual and measurement domains of market orientation. Although several different market orientation scales exist (e.g., Cadogan and Diamantopoulos, 1995; Kohli and Jaworski, 1990; Lichtenthal and Wilson, 1992; Narver and Slater, 1990; Ruekert, 1992), there is no consensus on which is the better measure. As market orientation is considered a core concept of marketing (Narver and Slater, 1990), further conceptual and empirical investigation of existing scales is warranted. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to conceptually and empirically (on psychometric grounds) compare an extended market orientation (EMO for notational purposes) scale with two existing market orientation constructs and scales. This is in the spirit of the comparative approach to theory testing (Sternthal et al., 1987) that argues a rigorous theory testing can be achieved by comparing the rival theoretical proposi-

tions. Because this approach demands a comparison be made on the grounds of a fit between the theoretical proposition and the empirical data, we first present how different market orientation scales are theoretically conceived and operationalized relative to other related constructs. We provide a conceptual review of market orientation, focusing on recent debate on construct definition and operationalization of market orientation scales. We then offer a model that organizes and reconciles two distinct market orientation conceptualizations, one behavioral and the other cultural. We introduce an EMO scale, which is built upon Kohli and Jaworskis (1990) conceptualization by specifically incorporating additional market factors into their scale. We compare the three measurement theories theoretically and empirically.

2. Two conceptualizations of market orientation One conceptualization and operationalization of a market orientation was provided by Kohli and Jaworski (hereafter referred to as KJ). Following Kings (1965) and others approaches, KJ conceptualize an organizations market orientation as implementation of the marketing concept (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990). The operationalization is consistent with the use of the market information research (Deshpande and Zaltman, 1982; Jaworski and Kohli, 1996; Maltz and Kohli, 1996; Menon and Varadarajan, 1992; Moorman, 1995; Sinkula, 1994) that places a particular emphasis on a

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +1-781-239-4363; fax: +1-781-2395020. E-mail address: matsuno@babson.edu (K. Matsuno). 0148-2963/$ see front matter D 2003 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(03)00075-4

K. Matsuno et al. / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 18

firms activities dealing with information pertaining to customer needs and the market environment that affects organizations. Specifically, a market orientation was conceived as an organizational process of (1) market intelligence generation, (2) dissemination and (3) responsiveness to such intelligence across departments. KJ provided a useful distinction and interpretation of the marketing concept and a market orientation from a behavioral process (implementation) perspective. A different conceptualization was offered by Narver and Slater (hereafter referred to as NS) who defined market orientation as organizational culture. NSs market orientation construct is seen as a composite of a firms orientation toward competitors, the firm and customers. NS see organizational culture as a driver of behaviors, and marketoriented behaviors do not manifest themselves in the organization if the culture lacks commitment to superior value for customers. 2.1. Reconciling the two conceptualizations of market orientation NS were very clear about the definition of the market orientation phenomenon as organizational culture: Market orientation is the organizational culture that most effectively and efficiently creates the necessary behaviors for the creation of superior value for buyers and thus continuous superior performance for the business (Narver and Slater, 1990, p. 21, emphasis added). Therefore, they conceived such culture as a causal antecedent to market-oriented behavior. Indeed, whether or not the construct of a market orientation is equivalent to culture (as defined by NS) or a set of behaviors (as defined by KJ) is a subject of heated debate (Deshpande and Farley, 1998a,b; Narver and Slater, 1998; Narver et al., 1998). Deshpande and Farley (1998a) investigated the correlation between the two different market orientation scales (NS and KJ) and the Deshpande et al. (1993) customer orientation scale. A factor analysis of the 44 individual items from the three scales suggested that 10 items with high loadings form a synthesized scale, named MORTN (Deshpande and Farley, 1998a). Their inductive analysis led them to conclude that market orientation is not a culture (as Deshpande and Webster, 1989 originally suggested) but rather a set of activities (i.e., a set of behaviors and processes related to continuous assessment of serving customer needs) (Deshpande and Farley, 1998a, p. 226). Narver and Slater (1998) strongly opposed the posi tion of Deshpande and Farley (1998a, p. 233): we hold that both logic and scholarly research strongly support the idea that a market orientation is nothing less than an organizations culture. NSs central rationale is that customerrelated activities are the manifestation of organizational belief and culture and it is the underlying culture that should be defined and measured as market orientation. The debate between Deshpande and Farley and NS directs us not only to the construct definition and reconcili-

ation issue but also to the operationalization of the construct (or measurement scale). In fact, NS operationalize the culture in terms of behavior to a great extent (Deshpande and Farley, 1998a,b; Jaworski and Kohli, 1996; Narver and Slater, 1998; Narver et al., 1998). Although organizational culture is a sociopsychological construct that is difficult to operationalize and measure, the persisting challenge for business is that, even if a promoting environment exists, corresponding behavior does not necessarily take place (Kopelman et al., 1990; Scott, 1992). This is exactly the same issue of the marketing concept for the last several decadesdifficulty in implementing a philosophy that many believe inherently correct. Furthermore, it can be argued that defining the antecedent (culture) in terms of a particular consequence is circular logic and poses great difficulty in empirical investigation, especially with regard to validity. In fact, NSs definition of market orientation is predicated by creation of superior value, a performance consequence. Thus, although culture seems to be promising as an internal environment antecedent to market-oriented behaviors, the chance of conceptual and empirical confounding from treating the two as one is not negligible with NSs scale. In fact, Deshpande and Farley (1998a,b) report that there are only two items that specifically tap into cultural values and argue that the two items do not belong to the synthesized scale of MORTN but to something else. We consider this as compelling evidence that NSs operationalization is confounded. On the other hand, KJs construct (a set of intelligencerelated behaviors) results from internal and external environmental antecedents. The internal task environment includes such factors as organizational structure and design (e.g., complexity, formalization, centralization and specialization/differentiation), performance measures and reward systems, top managements attitude toward risk and organ izational culture (Deshpande and Webster, 1989; Jaworski and Kohli, 1993; Narver and Slater, 1990; Ruekert et al., 1985; Webster, 1988; Zaltman et al., 1973). The external environment refers to the elements outside the organizational boundaries, such as market competitive structures (e.g., entry barriers, seller concentration and buyer power), industry/market characteristics (e.g., growth rate, cost and investment structure, technological dynamism and market turbulence) and regulatory factors (Day and Nedungadi, 1994; Narver and Slater, 1990; Porter, 1980). The result of the conduct (or response to the environments) is posited as firm performance, both financial and organizational (Jaworski and Kohli, 1993).

3. The development of an EMO model First, we conceive a generic conceptual causal model relative to a firms environments, conduct and consequences (Fig. 1) building on the classic structure-conduct-performance paradigm (Thorelli, 1977). Business performance

K. Matsuno et al. / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 18

Fig. 1. A generic conceptual causal model.

(consequence) is posited as a derivative of the interaction between the firm and the external and internal environments in which it operates (Vernon, 1972). Using this generic framework (Fig. 1) as a starting point, we conceptually reconcile the current debate by positioning NSs cultural construct as an antecedent to the conduct, KJs behavioral construct as a firms conduct and performance as a set of consequences of a firms conduct. Specifically, the model accommodates apparent differences in the two conceptualizations by distinguishing market orientation as organizational culture (an antecedent) from market orientation as a set of behaviors (firms conduct). This approach implies that (1) firms engage in a set of intelligence-related activities at varying degrees (conduct) as a response to the state of internal and external factors and (2) the extent to which a firm engages in such conduct determines market consequences. In sum, this generic model points out that each of the two different market orientation scales and measurement theories is conceived at a different level of abstraction. In the following sections, we propose an extended model of market orientation built on the generic model. This extended model incorporates various antecedents, an extended construct of market orientation (or EMO) as the focal construct, performance consequences of EMO and moderators on the relationships between EMO and the performance consequences. 3.1. The EMO: an integrated model and focal construct Despite the fact that the structure-conduct-performance paradigm (Thorelli, 1977; Vernon, 1972) and constituency-

based theory (Anderson, 1982; Connolly et al., 1980; Kotler, 1972; Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978; Sturdivant, 1977; Zeithaml and Zeithaml, 1984) provide strong support for a broad conceptualization of market orientation that includes multiple stakeholders, past researchers have conceptualized, operationalized and examined market orientation within a limited scope of domains, focusing primarily on customers and competition. If market orientation is an integral part of market economies, not incorporating other important elements seems to be a drawback of the two existing scales. Particularly, as it relates to NSs conception of market orientation as culture, the EMO conceptual model (Fig. 2) meaningfully resolves the two distinct definitions of market orientation. The model positions organizational culture as one of several internal antecedents to conduct (i.e., market orientation as a set of behaviors). The distinctions between environmental antecedents (internal or external) and a market orientation should be made and they should be modeled accordingly. Simultaneously, the breadth of market participants (e.g., competitors and customers) must be captured in the context of a firms managerial actions. The general conceptual model of EMO (Fig. 2) and its focal EMO construct, we argue, accommodates these two requirements. Specifically, the EMO scale extends the scope of stakeholders and marketplace factors to include suppliers, regulatory aspects, social and cultural trends and macroeconomic environment as other authors acknowledge (Jaworski and Kohli, 1996; Kohli et al., 1993). Similarly, Slater and Narver (1995) propose a broader conceptualization of a market that encompasses all relevant sources of competitive advantage

Fig. 2. The EMO conceptual model.

K. Matsuno et al. / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 18

and customer value. Unfortunately, neither of the scales by KJ or NS in their current form reflects this important advancement in construct domain. Thus, we developed and labeled a comprehensive construct, EMO. It incorporates more than just customers and competitors in the domain of organizational intelligencerelated activities. We define the focal EMO construct as a set of intelligence generation and dissemination activities and responses pertaining to the market participants (i.e., competitors, suppliers and buyers) and influencing factors (i.e., social, cultural, regulatory and macroeconomic factors). Therefore, from a theoretical perspective, we argue that the EMO has greater potential to explain a broader range of the phenomenon, is conceptually consistent with market orientation and provides a more accurate picture of the relationships between the antecedent environment, the firms conduct and performance consequences than do other models. In this broader model, the theoretical contributions of NS and KJ are found at different levels of abstraction: one at the internal environment level and another at the behavioral level.

Pretest 2) of 3300 manufacturing companies in the United States. The master list was available from a well-known commercial vendor in the United States. The profiles (employee size, annual sales and SIC code) of the 3300 manufacturing companies and the 300 companies (Pretest 1) and 1000 companies (Pretest 2) are available from the first author. In addition to reliability and construct evaluation, an important objective for this two-pretest process was to reduce the number of items to a more manageable number. Purification of items was conducted on both substantive and empirical grounds. After purification, the total number of items was 22. These 22 items are provided by Matsuno and Mentzer (2000).

5. Data collection In order to compare these three different scales [EMO, KJs (KJMO) and NSs (NSMO)], we randomly assigned the remaining 2000 marketing executives from the original mailing list (i.e., 3300 300 1000 = 2000) to one of the three different scales. The main purposes for this random assignment were to ensure that the chance of sampling error was minimized and that the results were empirically comparable across the scales. The first version was developed with the EMO scale items and seven economic performance variables (Appendix A) that were common across the versions. A second was made up of the KJMO scale (i.e., 32 items from Jaworski and Kohli, 1993) and common performance items. A third had the NSMO scale (i.e., 12 items from Narver and Slater, 1990, 1991) and the common performance items. For all three versions, layout, color and other physical characteristics were identical. For the market orientation items, a five-point Likert-type rating scale was developed and used (i.e., 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The seven economic performance items (overall, market share growth, sales growth, percentage of new product sales, return on asset, return on investment and return on sales) were all single-item subjective measures asking respondents about their business units performance relative to its major competitors on seven-point scales (i.e., 1 = far below competitors, 7 = far above competitors). Subjective measures were used for this study because (1) objective (i.e., certifiable by a third party) performance measures at the business unit level are practically impossible to obtain, (2) subjective measures reliably correlate with objective measures of performance (Dess and Robinson, 1984; Slater and Narver, 1994) and (3) subjective measures have been used in past market orientation performance studies (Narver and Slater, 1990, 1991; Jaworski and Kohli, 1993; Slater and Narver, 1994). The overall physical design and layout was based on the concept of the total design method (Dillman, 1978). We applied the same unit of analysis as the predecessors to this study, which is the SBU, or strategic business unit via

4. Development of the EMO scale A scale for the central construct (EMO) was developed. The overall methodology followed procedures recommended by Churchill (1979) and updated by Gerbing and Anderson (1988). The scale developed for this study evolved from a combination of exploratory qualitative in-depth interviews (a total of 12 business executives), a review of the market orientation literature and two survey pretests of the scale. The interview results suggest that managers conceive markets more broadly than customers and competition, specifically including such factors as macroeconomic elements, suppliers, social and cultural trends and regulatory environment. The domain of the construct was specified to include three categories of intelligence-related activities (intelligence generation, intelligence dissemination and responsiveness to the intelligence) regarding various market participants and market environments that are relevant to the degree of the organizations market orientation. With this domain in mind, a set of new items (a total of 37 items) was designed to capture a broader range of market elements that were either not covered at all or not captured specifically enough by KJs existing scale. These newly developed items were added to the original set of KJs market orientation scale items (Jaworski and Kohli, 1993; Kohli et al., 1993) (a total of 32 items) and collectively constituted the original candidate items for the EMO scale (a total of 69 items). After incorporating the editorial suggestions from the 12 business executives who participated in the in-depth interviews and 4 marketing academics in terms of the content, we conducted two pretests. The two pretests involved two random samples of 1300 marketing executives (300 for Pretest 1 and 1000 for

K. Matsuno et al. / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 18

a key informant approach (Jaworski and Kohli, 1993; Narver and Slater, 1990). The questionnaire items asked about a business unit the informant was knowledgeable about and responsible for. If a key informant was responsible for multiple business units, he/she was asked to choose one typical business unit as the focus of the responses. Data were collected through a self-administered written questionnaire.

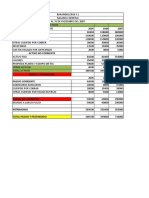

Table 1 Results: completely standardized solution Fit statistics and reliability (Cronbachs a) EMO (22 items) a=.85 c2 = 227.65 (df = 206) GFI = 0.88, AGFI = 0.85, PGFI = 0.72, NFI = 0.75, CFI = 0.97 IG (8 items) a=.65 ID (6 items) a=.75 RESP (8 items) a=.81 KJMO (32 items) a=.86 c2 = 476.64 (df = 461) GFI = 0.83, AGFI = 0.80, PGFI = 0.72, NFI = 0.61, CFI = 0.98 IG (10 items) a=.61 ID (8 items) a=.69 RESP (14 items) a=.81 NSMO (12 items) a=.67 c2 = 50.29 (df = 51) GFI = 0.96, AGFI = 0.94, PGFI = 0.63, NFI = 0.90, CFI = 1.00 CUST (4 items) a=.38 COMP (4 items) a=.45 INTER (4 items) a=.78

a

Path estimates (t statistic) IG-EMO ID-EMO RESP-EMO 0.69 (2.83) 0.95 (6.30) 0.63 (4.96)

6. Results A written questionnaire, cover letter and a postage-paid return envelope were mailed, with two follow-up reminder mailings to nonrespondents. The three different versions experienced slightly different response rates. The response rates were 40.8%, 42.2% and 48.3% for Version A (EMO scale), Version B (KJMO) and Version C (NSMO), respectively. For each version, presence of nonresponse bias was examined by applying MANOVA and univariate F-tests to the seven performance variables. Based on these tests for all the versions, there was no indication that the responses to the performance measures were significantly different based on the number of mailings received before the respondents actual response. In addition, the equivalency of the three different respondent groups (i.e., EMO, KJMO and NSMO) was examined by applying MANOVA to the seven performance variables across the three questionnaire types. Multivariate tests of significance (i.e., Pillais Trace, Wilks and Hottellings Trace) indicated there was no difference between the groups on these performance variables. 6.1. Unidimensionality of the scales The variance extracted (VE) at the first-order level was not satisfactory for any of the scales according to the wellaccepted criterion of being greater than 0.5 (Fornell and Lacker, 1981). The VE ranged 0.21 0.37 for the EMO, 0.15 0.26 for the KJMO and 0.26 0.49 for the NSMO, suggesting a high level of measurement errors relative to the standardized loadings. The second-order confirmatory factor analysis for each scale produced reasonable general fit indices, producing, for example, CFI of between 0.97 (EMO) (Table 1) and 1.00 (NSMO) (Table 1). All three scales had VE at the secondorder factor level greater than 0.5 (i.e., 0.59, 0.77 and 0.69 for EMO, KJMO and NSMO, respectively). A closer look at KJMO revealed that quite a few l coefficient estimates (not standardized) in the IG (1 item) and ID (7 items) dimensions were found to be nonsignificant at the a=.05 level (i.e., the t statistic < 1.96) due to a high level of standard errors of the estimates. In fact, the nonsignificant l coefficient estimates led to a nonsignificant LISREL estimate of the path between ID and KJMO, and caution should be exercised in interpreting the standardized estimates of the KJMO scale (Table 1). The data suggest

IG-KJMO ID-KJMO RESP-KJMO

0.84 (3.29) 0.82 (1.15)a 0.97 (6.05)

CUST-NSMO COMP-NSMO INTER-NSMO

0.78 (5.63) 0.82 (5.50) 0.89 (6.78)

Not significant at a=.05.

that the unidimensionality of the KJMO scale as a whole (in the second-order factor structure) is not supported without some further purification, which involves such procedures as item modifications and/or deletion particularly in the ID dimension. The second-order factor structures appear reasonable for both EMO and NSMO. Notably, the NSMO scale produced excellent fit statistics (c2 = 50.29 at df = 51, GFI = 0.96, AGFI = 0.94, PGFI = 0.63, NFI = 0.90, CFI = 1.00) (Table 1). The EMO scale, on the other hand, produced a slightly lower though very good fit. At the first-order level, EMOs CFI ranged from 0.94 to 1.00, exceeding the well-accepted level of 0.90 (Bearden et al., 1982). The EMO second-order fit statistics (Table 1) were also good (c2 = 227.65 at df = 206, GFI = 0.88, AGFI = 0.85, PGFI = 0.72, NFI = 0.75, CFI = 0.97) but not as good as the NSMOs. Note that the EMO scale contains 22 items while the NSMO scale contains only 12, which could account for the slightly lower fit of the EMO scale. Although both EMO and NSMO scales demonstrate adequate fit in the second-order factor structure, the reliability of the scales, however, is not extremely high for either scale. This is particularly notable given the number of items for each scale is relatively large, especially for EMO. The NSMO scale especially suffered from low Cronbachs a on two first-order dimensions (.38 for customer orientation and .45 for competitor orientation), while the interfunctional coordination dimension produced a reasonable a of .78. It was quite surprising that these reliability coefficients are

K. Matsuno et al. / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 18

substantially lower than those reported in NSs studies in the past. For example, in one of their studies (Slater and Narver, 1994), the reliability coefficients were reported as customer orientation (a=.878), competitor orientation (a=.726) and interfunctional coordination (a=.774). Although still relatively low, the EMOs first-order level reliabilities (IG = 0.65, ID = 0.75 and RESP = 0.81) were slightly greater than those of both NSMO and KJMO (IG = 0.61, ID = 0.69 and RESP = 0.81). 6.2. Predictive validity of market orientation scales To replicate the past performance-related studies of market orientation, a structural equation model was fit for each of the seven performance measures (dependent variables) separately with EMO and NSMO as independent variables. Since the KJMO scales proposed second-order factorial structure was found untenable in spite of the adequate fit, the KJMO scale is not examined for its predictive validity here. Thus, one model equates EMO and the performance measures (EMO model), while the second equates NSMO and the performance variables (NSMO model). Each structural parameter was estimated using LISREL 8, and the overall fit for each model was estimated by c2 goodness-of-fit statistics. The LISREL estimates for the b coefficients with regard to the dependent variables (ROA, ROI, ROS, SOM, SGRO, PCNTNP and OVERALL) are given in Table 2. The results show that both scales are positively related to all seven of the performance measures at the a=.05 level: a market orientation (measured in two different ways) was found to be positively correlated to the performance measures. Therefore, both EMO and NSMO scales were found to have predictive validity with regard to the performance

outcome measures. The magnitude of the b coefficients is greater for the NSMO scale than the EMO scale for five of the seven performance measures. The R2s suggest that the EMO seems to explain the variation of the efficiency measures (i.e., ROI, ROA and ROI) as well as or better than the NSMO, while the NSMO explains the variation of the effectiveness (i.e., SOM, SGRO and PCTNP) and the overall measures better than the EMO. However, given the fewer number of items than the EMO scale, the NSMO scale is more efficient in predicting the performance measures.

7. Implications and future research We took a comparative approach (Sternthal et al., 1987) to see if one theory could offer a better or more efficient explanation for the data. We compared the theories behind the KJMO and NSMO measures, proposed the EMO scale and presented evidence of the validity of the three different market orientation scales. However, based on scale reliability, limited unidimensionality and construct domain, no single scale examined here was found satisfactory. Several implications can be drawn. The first is fundamentally a conceptual one. In resolving different conceptualizations and operationalizations (Kohli and Jaworski, 1990; Narver and Slater, 1990), our theoretical position is that market orientation construct is a set of intelligence-related behaviors with a broader scope of factors in the market. How the domain of the construct is conceived and defined relative to other related constructs is a foundation of scale development. If a construct is not clearly defined at this early definition stage, we cannot hope to develop a scale that can be validated in a nomological network (Cronbach and Meehl, 1955; Peter, 1981). As Peter (1981, p. 207) pointed out, it is the theory and the nature of the construct which not only specify what empirical relationships are worth investigating but also determine whether empirical results support or invalidate a measure. Therefore, from the theoretical domain perspective, we argue that the KJMO scale is superior to NSMO scale for its consistency with the theory and scale operationalization, and the EMO scale is an improvement to the KJMO scale. Second, on empirical grounds, we are always better off when we are aware of the measurement properties of a scale and its rivals before using them. In relation to the reliability of the scales, the results are mixed. At both the entire scale level and the component level, the EMO scale had comparable or greater as (.85 at the entire scale level, between .65 and .81 at the component level) than the NSMO scale (.69 at the entire scale level, between .38 and 78 at the component level). However, with more items in the EMO scale than the NSMO scale, it suggests a greater efficiency of the NSMO scale. Overall, in fact, considering the number of items (22 for EMO, 32 for KJMO and 12 for NSMO), we conclude that the reliability of any of the scales is not high. In addition, although the VE for each scale was satisfactory

Table 2 Path coefficient estimates, t statistics and selected fit statistics: completely standardized solution EMO model (t statistic) LISREL estimates for performance measures b (ROA) b (ROI) b (ROS) b (SOM) b (SGRO) b (PCTNP) b (OVERALL) Model fit statistics c2 (df) c2 P-value GFI AGFI PGFI NFI PNFI CFI R2 0.39 0.46 0.42 0.35 0.42 0.32 0.34 (4.30) (5.13) (4.58) (3.78) (4.64) (3.38) (3.69) .16 .21 .17 .12 .18 .10 .12 0.40 0.41 0.36 0.50 0.46 0.39 0.48 (4.89) (4.99) (4.43) (6.39) (5.71) (4.75) (6.01) NSMO model (t statistic) R2 .16 .16 .13 .25 .21 .15 .23

338.83 (353) .70 0.87 0.84 0.70 0.82 0.71 1.00

99.30 (128) .97 0.95 0.92 0.64 0.94 0.70 1.00

K. Matsuno et al. / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 18

at the second-order level, it was not so at the first-order level for any of the three scales, suggesting lack of convergence at the first-order level. On this criterion of VE, NSMO is superior to either EMO or KJMO at both first-order and second-order factor levels. Clearly, more research efforts should be directed to improve the item convergence for the three scales. This would be a particularly worthy challenge for researchers because market orientation theory suggests a broader domain conceptualization (and therefore a broader item sampling domain), but such a breadth makes it more difficult to achieve a higher level of item convergence. Further research is clearly needed. Third, on unidimensionality (Table 1) and predictive validity (Table 2), the NSMO scale was found superior to and more efficient than either EMO or KJMO. The result was notable especially because the NSMO operationalization is confounded with behavioral aspects of market orientation and is inconsistent with the construct definition as an organizational culture. Between the two behavioral market orientation scales, however, the EMO scale has better internal consistency, unidimensionality and fewer items than the KJMO scale. With the 32 original KJMO items, the Intelligence Dissemination dimension was nonsignificant in the second-order factor structure. Conceptually, the EMO scale is built on a behavioral perspective, on which KJMO is also based; the relatively higher internal consistency over KJMO is a meaningful advancement for measuring a market orientation from a behavioral perspective. The advantages are meaningful because the EMO scale is conceptually improved, capturing a broader spectrum of market factors (i.e., suppliers, regulatory aspects, social/ cultural trends and macroeconomic environment) than the existing market orientation scales. Empirical correspondence between culture and a firms market orientation has not been established to date (Desh pande and Farley, 1998a,b). The challenge of grappling with this very complex construct first lies in construct specification. Narver et al. (1998) argue that market-oriented behaviors do not consistently occur unless a promoting organizational culture is present. Indeed, it is conceivable that the organizational culture articulated by Narver et al. (1998) may be a necessary but not sufficient condition to market-oriented behaviors. In order to answer this intriguing question, a measure of culture with discriminant validity relative to a behavioral construct of market orientation like ours needs to be established. Therefore, to establish a market orientation scale, the first critical step is identifying one or more facets of organizational culture that are directly relevant to the intelligence-related behavioral concept of market orientation. Development of a more definitive market orientation scale, therefore, has to wait for a better understanding of how organizational culture induces market-oriented behaviors. We encourage more research devoted to understanding the process of market orientation. The challenge of grappling with the construct of culture lies also in the data collection method. Specifically, culture

is an organization level construct and therefore needs to be measured at such a level. However, many studiesincluding the present oneused the key informant approach. This may be appropriate for measuring a climate, an individual level construct, but poses a threat to the construct validity of culture as an organizational construct (James et al., 1990). Future research should employ the multiple informant approach to measure this organizational and systems construct (James et al., 1990) more directly.

Appendix A. Economic performance measures

Performance variable Performance-OVERALL Performance-Market share growth (SOM) Performance-Sales growth (SGRO) Performance-Percent of new product sales (PCTNP) Performance-ROS Performance-ROA Performance-ROI

Item Our business units overall performance relative to major competitors last year. Our business units market share growth in our primary market last year. Our business units sales growth relative to major competitors last year. Percentage of sales generated by new products last year relative to major competitors. Our business units return on sales (ROS) relative to major competitors last year. Our business units return on assets (ROA) relative to major competitors last year. Our business units return on investment (ROI) relative to major competitors last year.

References

Anderson PF. Marketing, strategic planning and the theory of the firm. J Mark 1982;46:15 26 [Spring]. Bearden WO, Sharma S, Teel JE. Sample size effects of chi square and other statistics used in evaluating causal models. J Mark Res 1982;14: 396 402 [August]. Cadogan JW, Diamantopoulos A. Narver and Slater, Kohli and Jaworski and the market orientation construct: integration and internationalization. J Strat Mark 1995;3:41 60. Churchill GA. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J Mark Res 1979;16:64 73 [February]. Connolly T, Conlon EJ, Deutsch SJ. Organizational effectiveness: a multiple-constituency approach. Acad Manage Rev 1980;5(2):211 7. Cronbach LJ, Meehl PE. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychol Bull 1955;52:281 302 [July]. Day GS, Nedungadi P. Managerial representations of competitive advantage. J Mark 1994;58:31 44 [April]. Deshpande R, Farley JU. Measuring market orientation: a generalization and synthesis. J Mark Focus Manage 1998a;2:213 32. Deshpande R, Farley JU. The market orientation construct: correlations, culture, and comprehensiveness. J Mark Focus Manage 1998b;2: 237 9. Deshpande R, Webster Jr FE. Organizational culture and marketing: defining the research agenda. J Mark 1989;53:3 15 [January]. Deshpande R, Zaltman G. Factors affecting the use of market research information: a path analysis. J Mark Res 1982;19:14 31 [February]. Deshpande R, Farley JU, Webster Jr FE. Corporate culture, customer orientation, and innovativeness in Japanese firms: a quadrad analysis. J Mark 1993;57:22 7 [January].

K. Matsuno et al. / Journal of Business Research 58 (2005) 18 of the programmatic and market-back approaches. Marketing Science Institute Working Paper No. 91-128. Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute; 1991. Narver JC, Slater SF. Additional thoughts on the measurement of market orientation: a comment on Deshpande and Farley. J Mark Focus Manage 1998;2:233 6. Narver JC, Slater SF, Tietje B. Creating a market orientation. J Mark Focus Manage 1998;2:241 55. Peter PJ. Construct validity: a review of basic issues and marketing practices. J Mark Res 1981;18:133 45 [May]. Pfeffer J, Salancik GR. The external control of organizations: a resource dependence perspective. New York (NY): Harper & Row; 1978. Porter ME. Competitive strategy: techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. New York (NY): Free Press; 1980. Ruekert RW. Developing a market orientation: an organizational strategy perspective. Int J Res Mark 1992;9:225 45. Ruekert RW, Walker Jr OC, Roering KJ. The organization of marketing activities: a contingency theory of structure and performance. J Mark 1985;49:13 25 [Winter]. Scott WR. Organizations: rational, natural, and open systems. 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Prentice-Hall; 1992. Sinkula JM. Market information processing and organizational learning. J Mark 1994;58:35 45 [January]. Slater SF, Narver JC. Does competitive environment moderate the market orientation performance relationship? J Mark 1994;58:46 55 [January]. Slater SF, Narver JC. Market orientation and the learning organization. J Mark 1995;59:63 74 [July]. Sternthal B, Tybout AM, Calder BJ. Confirmatory versus comparative approaches to judging theory tests. J Consum Res 1987;14:114 25 [June]. Sturdivant FD. Business and society: a managerial approach. Homewood (IL): Richard D. Irwin; 1977. Thorelli HB. Strategy + structure = performance. Bloomington (IN): Indiana Univ Press; 1977. Vernon JM. Market structure and industrial performance: a review of statistical findings. Boston (MA): Allyn and Bacon; 1972. Webster Jr FE. The rediscovery of the marketing concept. Bus Horiz 1988; 29 39 [May June]. Zaltman G, Duncan R, Holbek J. Innovations and organizations. New York (NY): Wiley; 1973. Zeithaml CP, Zeithaml VA. Environmental management: revising the marketing perspective. J Mark 1984;48:46 53 [Spring].

Dess GG, Robinson Jr RB. Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: the case of privately-held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strat Manage J 1984;5:265 73 [July September]. Dillman DA. Mail and telephone survey: the total design method. New York (NY): Wiley; 1978. Fornell C, Lacker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 1981;18:39 50 [February]. Gerbing DW, Anderson JC. An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. J Mark Res 1988; 25:186 92 [May]. James LR, James LA, Ashe DK. The meaning of organizations: the roles of cognition and values. In: Schneider B, editor. Organizational climate and culture. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 1990. p. 40 84. Jaworski BJ, Kohli AK. Market orientation: antecedents and consequences. J Mark 1993;57:53 70 [July]. Jaworski BJ, Kohli AK. Market orientation: review, refinement, and roadmap. J Mark Focus Manage 1996;1(2):119 35. King RL. The marketing concept. Science in marketing. New York (NY): Wiley; 1965. p. 70 97. Kohli AK, Jaworski BJ. Market orientation: the construct, research propositions, and managerial implications. J Mark 1990;54:1 18 [April]. Kohli AK, Jaworski BJ, Kumar A. MARKOR: a measure of market orientation. J Mark Res 1993;30:467 77 [November]. Kopelman RE, Brief AP, Guzzo RA. The role of climate and culture in productivity. In: Schneider B, editor. Organizational climate and culture. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 1990. p. 282 318. Kotler P. A generic concept of marketing. J Mark 1972;36:46 54 [April]. Lichtenthal JD, Wilson DT. Becoming market oriented. J Bus Res 1992; 24:191 207. Maltz E, Kohli AK. Market intelligence dissemination across functional boundaries. J Mark Res 1996;33:47 61 [February]. Matsuno K, Mentzer JT. The effects of strategy type on the market orientation performance relationship. J Mark 2000;64:1 16 [October]. Menon A, Varadarajan PR. A model of marketing knowledge use within firms. J Mark 1992;56:53 71 [October]. Moorman C. Organizational market information processes: cultural antecedents and new product outcomes. J Mark Res 1995;32:318 35 [August]. Narver JC, Slater SF. The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. J Mark 1990;54:20 35 [October]. Narver JC, Slater SF, Becoming more market oriented: an exploratory study

También podría gustarte

- Cec 103. - Workshop Technology 1Documento128 páginasCec 103. - Workshop Technology 1VietHungCao92% (13)

- PDS OperatorStationDocumento7 páginasPDS OperatorStationMisael Castillo CamachoAún no hay calificaciones

- Max Born, Albert Einstein-The Born-Einstein Letters-Macmillan (1971)Documento132 páginasMax Born, Albert Einstein-The Born-Einstein Letters-Macmillan (1971)Brian O'SullivanAún no hay calificaciones

- Water Reducing - Retarding AdmixturesDocumento17 páginasWater Reducing - Retarding AdmixturesAbdullah PathanAún no hay calificaciones

- Control PhilosophyDocumento2 páginasControl PhilosophytsplinstAún no hay calificaciones

- Homa 2 CalculatorDocumento6 páginasHoma 2 CalculatorAnonymous 4dE7mUCIH0% (1)

- Qualcomm LTE Performance & Challenges 09-01-2011Documento29 páginasQualcomm LTE Performance & Challenges 09-01-2011vembri2178100% (1)

- Marketing Concept NPODocumento26 páginasMarketing Concept NPOKristy LeAún no hay calificaciones

- Tablas Modulo1 PDFDocumento5 páginasTablas Modulo1 PDFWilfredo RiveraAún no hay calificaciones

- Balance GeneralDocumento3 páginasBalance Generaledgardo duranAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 4 Audit Evidence Documentation Compatibility ModeDocumento33 páginasChapter 4 Audit Evidence Documentation Compatibility ModeAnh PhamAún no hay calificaciones

- Contabilidad de Costos Sinesterra 50 - 89Documento40 páginasContabilidad de Costos Sinesterra 50 - 89ariel502010Aún no hay calificaciones

- Narver and Slater, Kohli and Jaworski and The Market Orientation Construct: Integration and InternationalizationDocumento21 páginasNarver and Slater, Kohli and Jaworski and The Market Orientation Construct: Integration and Internationalizationbennie7390Aún no hay calificaciones

- Jaworski and Kohli 1993Documento19 páginasJaworski and Kohli 1993stiffsn100% (1)

- Cultural and Behavioral Adoption of Market Orientation FormsDocumento10 páginasCultural and Behavioral Adoption of Market Orientation FormsbalbalAún no hay calificaciones

- Market Orientation: Antecedents and ConsequencesDocumento19 páginasMarket Orientation: Antecedents and ConsequencesSalas MazizAún no hay calificaciones

- The Effects of Strategy Type On The Market Orientation-Performance RelationshipDocumento17 páginasThe Effects of Strategy Type On The Market Orientation-Performance RelationshipEmmy SukhAún no hay calificaciones

- Kirca Et Al 2005 Market Orientation A Meta Analytic Review and Assessment of Its Antecedents and Impact On PerformanceDocumento18 páginasKirca Et Al 2005 Market Orientation A Meta Analytic Review and Assessment of Its Antecedents and Impact On PerformanceBart WolsingAún no hay calificaciones

- Petency MODocumento21 páginasPetency MOjohnalis22Aún no hay calificaciones

- Market Orientation in Pakistani CompaniesDocumento26 páginasMarket Orientation in Pakistani Companiessgggg0% (1)

- Market OrientationDocumento40 páginasMarket OrientationBoogii EnkhboldAún no hay calificaciones

- Interfunctional Dynamics and Firm Performance: A Comparison Between Firms in Poland and The United StatesDocumento19 páginasInterfunctional Dynamics and Firm Performance: A Comparison Between Firms in Poland and The United StatesLeila BenmansourAún no hay calificaciones

- An Analysis of The MKTOR and MARKOR Measures of MaDocumento12 páginasAn Analysis of The MKTOR and MARKOR Measures of MaArvind ShuklaAún no hay calificaciones

- Kara 2005Documento14 páginasKara 2005Nicolás MárquezAún no hay calificaciones

- Theory, Research and Practice in Library Management 8: Market OrientationDocumento10 páginasTheory, Research and Practice in Library Management 8: Market OrientationWan Ahmad FadirAún no hay calificaciones

- Jurnal CRMDocumento19 páginasJurnal CRMYudha PriambodoAún no hay calificaciones

- Cultural vs. Operational Market Orientation and Objective vs. Subjective Performance: Perspective of Production and OperationsDocumento33 páginasCultural vs. Operational Market Orientation and Objective vs. Subjective Performance: Perspective of Production and Operationssamas7480Aún no hay calificaciones

- Corporate Culture, Customer Orientation, and Innovativeness Japanese Firms: A Quadrad AnalysisDocumento15 páginasCorporate Culture, Customer Orientation, and Innovativeness Japanese Firms: A Quadrad AnalysisAndrés GómezAún no hay calificaciones

- Effect of SMO On Manufacturer's Trust - Zhao 2005pdfDocumento10 páginasEffect of SMO On Manufacturer's Trust - Zhao 2005pdfElaine Antonette RositaAún no hay calificaciones

- Market Orientation and Entrepreneurial Culture Drive Business ProfitabilityDocumento5 páginasMarket Orientation and Entrepreneurial Culture Drive Business ProfitabilityIng Raul OrozcoAún no hay calificaciones

- MB V8 A3 Farrell PDFDocumento11 páginasMB V8 A3 Farrell PDFHexaNotesAún no hay calificaciones

- Relationship Between Desired & Achieved Market Orientation LevelsDocumento17 páginasRelationship Between Desired & Achieved Market Orientation Levels:-*kiss youAún no hay calificaciones

- The Journey From Market Orientation To Firm Performance: A Comparative Study of US and Taiwanese SmesDocumento13 páginasThe Journey From Market Orientation To Firm Performance: A Comparative Study of US and Taiwanese Smesbandi_2340Aún no hay calificaciones

- Jaworski Jaworski and Kohliand KohliDocumento19 páginasJaworski Jaworski and Kohliand KohliSmucek87Aún no hay calificaciones

- Family Business and Market Orientationthesis PDFDocumento19 páginasFamily Business and Market Orientationthesis PDFFrancis RiveroAún no hay calificaciones

- Measuring Marketing OrientationDocumento2 páginasMeasuring Marketing OrientationFrancis RiveroAún no hay calificaciones

- Being Entrepreneurial and Market Driven: Implications For Company PerformanceDocumento18 páginasBeing Entrepreneurial and Market Driven: Implications For Company PerformanceEsrael WaworuntuAún no hay calificaciones

- Linking Strategic and Market Orientations To Organizat 2013 Procedia SociaDocumento7 páginasLinking Strategic and Market Orientations To Organizat 2013 Procedia SociabalbalAún no hay calificaciones

- Master of Business Adminstration Marketing OrientationDocumento11 páginasMaster of Business Adminstration Marketing OrientationQuảng Nguyễn ĐìnhAún no hay calificaciones

- RSM Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, andDocumento49 páginasRSM Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, andMahipal18Aún no hay calificaciones

- American Marketing AssociationDocumento23 páginasAmerican Marketing AssociationpadmavathiAún no hay calificaciones

- A New Perspective On Market Dynamics: Market Plasticity and The Stability-Fluidity DialecticsDocumento21 páginasA New Perspective On Market Dynamics: Market Plasticity and The Stability-Fluidity DialecticslomahanaAún no hay calificaciones

- ATM PositioningDocumento17 páginasATM PositioningNguyễn Tiến LâmAún no hay calificaciones

- Executive Insights. Market Orientation of Mexican CompaniesDocumento18 páginasExecutive Insights. Market Orientation of Mexican CompaniesRicardo Santos GarcíaAún no hay calificaciones

- KOTTIKA - Market-Driving - Strategy - and - Personnel - Attributes - 2018Documento41 páginasKOTTIKA - Market-Driving - Strategy - and - Personnel - Attributes - 2018Ferdous AminAún no hay calificaciones

- Organizational Culture and Job SatisfactionDocumento18 páginasOrganizational Culture and Job SatisfactionryarezsaAún no hay calificaciones

- Critical Perspective On Motivation TheoriesDocumento20 páginasCritical Perspective On Motivation TheoriesHoang Vy Le DinhAún no hay calificaciones

- Positioning Strategies of Services, BlanksonDocumento16 páginasPositioning Strategies of Services, BlanksonKatarina PanićAún no hay calificaciones

- Market Orientation Kohli and JaworskiDocumento19 páginasMarket Orientation Kohli and JaworskiSara KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Towards An Institution-Based View of Business Strategy: 2002 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Manufactured in The NetherlandsDocumento18 páginasTowards An Institution-Based View of Business Strategy: 2002 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Manufactured in The NetherlandsSurekha NayakAún no hay calificaciones

- Article 2Documento17 páginasArticle 2Feven WenduAún no hay calificaciones

- The Measurement of Strategic Orientation and Its Efficacy in Predicting Financial PerformanceDocumento21 páginasThe Measurement of Strategic Orientation and Its Efficacy in Predicting Financial PerformanceDwitya AribawaAún no hay calificaciones

- Venter, P, Wright, A & Dibb, S 2015, Performing Market SegmentationDocumento36 páginasVenter, P, Wright, A & Dibb, S 2015, Performing Market SegmentationAhmad DarojiAún no hay calificaciones

- Deshpande 1989Documento14 páginasDeshpande 1989Jihene ChebbiAún no hay calificaciones

- Zeljko BunicDocumento17 páginasZeljko BunicGoltman SvAún no hay calificaciones

- American Marketing AssociationDocumento16 páginasAmerican Marketing AssociationMohamed SellamnaAún no hay calificaciones

- Ikea Ki Kya Aat GeDocumento37 páginasIkea Ki Kya Aat GeFurqangreatAún no hay calificaciones

- Capabilities and Financial PerformanceDocumento17 páginasCapabilities and Financial Performancemesay83Aún no hay calificaciones

- Converging On A New Theoretical Foundation For SellingDocumento18 páginasConverging On A New Theoretical Foundation For SellingJorge IvanAún no hay calificaciones

- Capabilities For Market-Shaping - Triggering and Facilitating Increased Value CreationDocumento24 páginasCapabilities For Market-Shaping - Triggering and Facilitating Increased Value CreationMariaAún no hay calificaciones

- Marketing and InnovationDocumento10 páginasMarketing and Innovationmedusa alfaidzeAún no hay calificaciones

- Kohli and Jaworski - Market OrientationDocumento19 páginasKohli and Jaworski - Market Orientationprayas_taraniAún no hay calificaciones

- How Context Frames Exchange and Value Co-CreationDocumento15 páginasHow Context Frames Exchange and Value Co-CreationTariq Waheed QureshiAún no hay calificaciones

- Prikaz Literature Za Ok, Liderstvo I PromeneDocumento34 páginasPrikaz Literature Za Ok, Liderstvo I PromeneDanka GrubicAún no hay calificaciones

- Toward A Deeper Understanding of Service PDFDocumento17 páginasToward A Deeper Understanding of Service PDFTriyoga RahmawanAún no hay calificaciones

- 10.1007@s11002 020 09529 5Documento12 páginas10.1007@s11002 020 09529 5The Armwrestling HubAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 s2.0 S0019850106000836 MainimpDocumento15 páginas1 s2.0 S0019850106000836 Mainimpsamas7480Aún no hay calificaciones

- 2.6 Rational Functions Asymptotes TutorialDocumento30 páginas2.6 Rational Functions Asymptotes TutorialAljun Aldava BadeAún no hay calificaciones

- Impedance Measurement Handbook: 1st EditionDocumento36 páginasImpedance Measurement Handbook: 1st EditionAlex IslasAún no hay calificaciones

- MITRES 6 002S08 Chapter2Documento87 páginasMITRES 6 002S08 Chapter2shalvinAún no hay calificaciones

- Lesson 1Documento24 páginasLesson 1Jayzelle100% (1)

- R8557B KCGGDocumento178 páginasR8557B KCGGRinda_RaynaAún no hay calificaciones

- Jaguar Land Rover Configuration Lifecycle Management WebDocumento4 páginasJaguar Land Rover Configuration Lifecycle Management WebStar Nair Rock0% (1)

- Technical Data: Pump NameDocumento6 páginasTechnical Data: Pump Nameسمير البسيونىAún no hay calificaciones

- UnderstandingCryptology CoreConcepts 6-2-2013Documento128 páginasUnderstandingCryptology CoreConcepts 6-2-2013zenzei_Aún no hay calificaciones

- Reference Mil-Aero Guide ConnectorDocumento80 páginasReference Mil-Aero Guide ConnectorjamesclhAún no hay calificaciones

- Data AnalysisDocumento7 páginasData AnalysisAndrea MejiaAún no hay calificaciones

- Turbine Buyers Guide - Mick Sagrillo & Ian WoofendenDocumento7 páginasTurbine Buyers Guide - Mick Sagrillo & Ian WoofendenAnonymous xYhjeilnZAún no hay calificaciones

- Design of Shaft Straightening MachineDocumento58 páginasDesign of Shaft Straightening MachineChiragPhadkeAún no hay calificaciones

- ENGG1330 2N Computer Programming I (20-21 Semester 2) Assignment 1Documento5 páginasENGG1330 2N Computer Programming I (20-21 Semester 2) Assignment 1Fizza JafferyAún no hay calificaciones

- Kalayaan Elementary SchoolDocumento3 páginasKalayaan Elementary SchoolEmmanuel MejiaAún no hay calificaciones

- Biogen 2021Documento12 páginasBiogen 2021taufiq hidAún no hay calificaciones

- Pumps - IntroductionDocumento31 páginasPumps - IntroductionSuresh Thangarajan100% (1)

- User Mode I. System Support Processes: de Leon - Dolliente - Gayeta - Rondilla It201 - Platform Technology - TPDocumento6 páginasUser Mode I. System Support Processes: de Leon - Dolliente - Gayeta - Rondilla It201 - Platform Technology - TPCariza DollienteAún no hay calificaciones

- Shares Dan Yang Belum Diterbitkan Disebut Unissued SharesDocumento5 páginasShares Dan Yang Belum Diterbitkan Disebut Unissued Sharesstefanus budiAún no hay calificaciones

- M.E. Comm. SystemsDocumento105 páginasM.E. Comm. SystemsShobana SAún no hay calificaciones

- Python - How To Compute Jaccard Similarity From A Pandas Dataframe - Stack OverflowDocumento4 páginasPython - How To Compute Jaccard Similarity From A Pandas Dataframe - Stack OverflowJession DiwanganAún no hay calificaciones

- PDF Solution Manual For Gas Turbine Theory 6th Edition Saravanamuttoo Rogers CompressDocumento7 páginasPDF Solution Manual For Gas Turbine Theory 6th Edition Saravanamuttoo Rogers CompressErickson Brayner MarBerAún no hay calificaciones

- Submittal Chiller COP 6.02Documento3 páginasSubmittal Chiller COP 6.02juan yenqueAún no hay calificaciones

- Eurotech IoT Gateway Reliagate 10 12 ManualDocumento88 páginasEurotech IoT Gateway Reliagate 10 12 Manualfelix olguinAún no hay calificaciones