Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Clase 2 Zimmer 2010 Voucher

Cargado por

Ró Stroskoskovich0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

4 vistas8 páginaseconomía política educación

Derechos de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

PDF o lea en línea desde Scribd

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoeconomía política educación

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como PDF o lea en línea desde Scribd

0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

4 vistas8 páginasClase 2 Zimmer 2010 Voucher

Cargado por

Ró Stroskoskovicheconomía política educación

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como PDF o lea en línea desde Scribd

Está en la página 1de 8

i

:

The Efficacy of Educational Vouchers*

R Zimmer, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Ml, USA

E Bettinger, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA,

© 2010 Elsevier Lt, lights reserved

Glossary

Children Scholarship Fund - Scholarship program

for students to attend private schools funded by the

Walton Family Foundation

Indirect effects ~ Erects on students not ulizing

‘vouchers to attend private schools.

‘Means-tested— A ctterion that uses the ability to

;pay as means of being eligible for a voucher.

PACES program — A Columbian program otfered

‘educational vouchers to over 144 000 low-income

‘students throughout Colombia from 1992 to 1997.

‘Scholarships - While both vouchers and

‘scholarships are entitlements to attend a private

‘school, vouchers are publicly funded while

‘scholarships are privately funded

‘Seetarian schools School affliated with

particular faith oF rligion

‘Selection bias — Estimated etfect of programs could

be biased because participants have chosen to

participate, whichis not captured by the econometric.

‘model.

‘Selt-selecting — Students choose to attend a private

‘school.

Vouchers —A governmentfinanced enttlement that

students and their families could use to attend any

‘school, including private schools.

Introduction

Advocates for vouchers argue that vouchers create incen-

tives for schools to compete for students and that such

‘competition can make all schools

efficient. Milton Friedman originally proposed vouchers

as a government-financed entitlement that students and

their families could use to attend any school, including

private schools (Friedman, 1955, 1962). Over time, sup-

post for voucher programs has come from diverse groups

such as conservative pro-marker advocates (including

Friedman), Roman Catholic bishops hoping to reinvigo~

rate parochial schools in urban cities, and minority advo

cacy groups.

we effective and

“The review an abbreviated vention of or reson review (Zimmer

and Betinger, 2007.

Voucher opponents argue voucher programs cream

skim the best students and

inequities if selection into voucher programs falls along

racial or economic divides, They claim that by

public school enrolments, vouchers intensify the fiscal

rains already felt by public schools.

Debates over vouchers have increased in the last

decade of s0 with the advent of publicly funded voucher

programs in Milwaukee, Cleveland, and Florida, Addition

ally, he inerease in the number of foundations and phila

st vouchers can increase

reducing

thropists providing private money for students to attend

private schools has also increased the public awareness of

voucher programs. Outside of the United States, voucher

like programs have also increased in popularity; and while

the motivation for these voucher programs differs from

those in the US, debates over these programs rage world-

wide, In this article, we examine many of the claims and

counterclaims of the debate by surveying the research

literature on both domestic and incesnationsl programs.

In reviewing the existing voucher literature, we focus

exclusively on empirical evidence on vouchers and do not

include a review of other forms of school choice includ

ing charter schools, home schooling, or the effectiveness

of private schools generally. While some research has

‘extended beyond actdemic and behavioral outcomes or

the distributional effects of Voucher programs and exam-

ined the effects of voucher programs on residential hous

ing markets (Nechyba, 2000), cos effectiveness of voucher

prograns (Levin, 2002), on subsequent public support for

‘vouchers, or lack thereof Brunner and Imazeki, 2006) and

‘on who wins and loses under voucher programs (Epple and

Romano, 1998, 2003), we only discuss these broader effects

to the extent that the studies shed light on the specific

‘voucher programs that we review

‘This is not the first review of vouchers programs (eg,

“itomer and Bettinger, 2007, Gill eal, 2001; Levin, 2002

McEwan, 2000, 2008). These reviews include the concep=

‘alization of, and rationale fos, voucher programs as well

as evidence onthe efficacy of vouchers. This article builds

‘on these reviews, but focuses on the achievement and

behavioral effects of vouchers on students and the effece

these programs have on access and integration

Structure of Voucher Plans

Voucher programs differ greatly in their specific design

Much of this variation is related to the differences in che

343

i

:

344 _The Efficacy of Educational Vouchers

motivation for vouchers among the voucher advocates

(Levin, 2007 Handbook) For example, many conservatives

believe that flat-rate, modest vouchers can increase effi-

shrough increased competition (eg, Friedman,

Other proponents argue that means-tested

vouchers can promote equity by providing berter educa~

tional opporcunities to low-income families in inner-city

schools, Programs also differ in their advacacy of subsidies

for transportation, degree of information availability, reg-

ulation of admission policies, and accountability mecha

isms (Jencks, 1970, Levin, 2002). In practice, voucher

programe differ substantially in their level of support,

the target population, and admission of sectarian schools,

“The various programmatic details change wit

to who participates inthe voucher program and are likely to

influence the generalizability of individual programs and

studies. For instance, programs that restrict participation

1 low-income students are likely co have different disei-

Dutional effects than 2 universal voucher program, Pro-

grams that allow scudents to attend sectarian schools are

also likely to attract a particular set of students ~ specifically

students seeking religious instruction opportunities. Finally,

the scale of the programs may affect whether these pro=

‘grams will generate general equilibrium effects that may be

‘even larger than the localized effects of voucher programs

(eg, Nechyba, 2000; Epple and Romano, 1998, 2003).

AAs the programmatic design can affect outcomes this

icle, as in our previous review, highlights the details of

‘each voucher program and the associated outcomes indi-

vidually, We synthesize che results in the final section and

provide a summary of the programs and outcomes in

Table 1

reference

Domestic Voucher Programs

Domestic voucher programs have been funded either by

public taxes or private donations, primarily through phi-

lanthropists or foundations. While the scale and regula

tion of public and privately programs may differ, they are

similar in that they both provide a subsidy for students to

axtend private schools

Publicly Funded Programs

The Milwaukee voucher program

The most visible domestic voucher program began in

Milwaukee in 1990, The program focused on low-income

students, The program started small being capped at 1%

of the school distrie’s population, In examining the pro-

gram, Witte (2000) compared the perf

students to that of all other students in the Milwaukee

school system finding no differences incest scores.

Greene ef al (1997, 1998), found increases in reading

and math test scores when they compared outcomes for

ance of voucher

voucher recipients who had stayed in voucher schools for

multiple years to outcomes for a comparison group of

students who had wanted to use the voucher but could

not because of a lack of space. These divergent results led

to an often heated debate over the results and methodol-

ogies (eg, Mitgang and Connell, 2003; McEwan, 2000)

Rouse (1998) attempted to resolve the controversy: Rouse

took advantage of the face that oversubscribed schools

used randomization to assign vouchers. (McEwan (2007)

discusses how randomization is the gold standard in eval-

uuative research). Rouse found slight positive, significa

effects of the voucher program in math test scores, but

none in reading.

Milwaukee's vou

et experience also sheds light on

the impact voucher programs can have on access and racial

integration, African-Americans made up over 62% of

the voucher population, Hispanics made up about 13%

(WLAB, 2000}, The program successfully targeted low

income families with the average family income for pro-

gram participants being around US$11 600 (Witce, 2000

Other snudies showed that the voucher parents had slightly

higher educational levels (Rouse, 1998; Wite, 1996, Wiete

and Thor, 1996) than other parents in Milwaukee.

While the early Milwaukee program offered insights

to policymakers, the small scale of the program limited

the policy implications. In 1995, the state of Wisconsin

greatly expanded the scholutship cap and the range of

private schools that students could attend. These changes

dramatically redefined the scope of the program. While

only 341 students attended seven private schools in 1991,

over 15000 students attended dozens of sectarian and non-

sectarian schools by the 2004-05 school year (Gill etal,

2001). This expansion led some researchers co investigate

‘whether Milwaukee's program resulted in changes in nearby

public schools (eg, Hoxby, 2005). Unfortunately, the ex

panded program did not require testing within the priv

axe schools, which resulted in no new studies of the program.

‘commissioned study (funded by the Bradley and.

Joyce Foundations among others) seeks to reevaluate the

Milwaukee voucher program by having private schools

voluntarily administer a standardized test

The Cleveland voucher program

In 1995, the Cleveland Monicipal School District began

The program was initially intended to allow vouchers to

bbe used at sectarian schools; however, courr decisions

immediately blocked this provision. Not ur

years later were students allowed to choose among both

sectarian and nonsectarian schools In 2007, Cleveland’s

program served over 6000 stud

Cleveland's voucher progr

answers about the program's impact on academic achieve

ment, As in the Milwaukee progeam, the problem with

the evaluations was whether the researchers used an ade~

{quate comparison group. The most often cited evaluation

n has not yielded clear

305,

Tho Efficacy of Educational Vouchers

punoiByeea

ex

800

uepns ue Bupuedep

Lo pusdap syoaya s198n uo 2249 ON

201008 ju oBBas0U4 opiartuayers ON

spooye anton

si98n Uo 819949 ON

501098 180) aseo10u) spi-worsig

onenpesé

pouse YB ue sao onnsod

vonenpesé

tooyes yBiy ue soy annsog

‘i601 pue porsjdisoo

‘1604 jooyos Uo 532949 349504

“suaiines 1o42non Bue

“suepms 1 95 fue 0) 2842 ON

swuapris

yx so0ye aansog

oeig Buowe A

syonues yum suotssouBoy

sjonueo im suojssouboy

sjonueo yim suolseeuboy,

sjonuco yum suotssouboy

uonedeSBe:sos1ueo yim SueIsaAoy

Jepou uonostes veuro0y)

sjonueo yim suojssaib0y

‘souaserd

_euan0n 0} ofgeyes eWaLNNU

suayonon jo vane zope

‘vayonon jo uojeziopuey,

siayanon jo uoqeziuopuey

siasn teyonon

siosn toyonon

siasn seyanen

siasn 1oyonon

worse e080)

issn soysnon

si9sn anon,

worsAs 89%

‘sjo0y9s jeuonea0n

1 siosn soyenon

issn soyonen

siasn eyanen

siesn soysren

siasn soyenon

siasn eyenon

(002) wewyo.

(002) owes pue ue aoWy

tooz) vemaon

(cop2) ezanyues pu ‘seiaauon ‘onese

(002) einbin pue vost

(9661

(oz) Pa

(661) tion ewoy pue e204

(6002) e631 eno,

(e002) eipenees pur sowery e6uneR

(e002) ow pue vebunieg yeabuy

(2o02) 8p

ue vouery woojg vebunieg suBuy quire

(©002) ums pue

(02) naz pur 0694

‘@o02)

uostajeg puE namon (z00%) 18 4EHY

eiBoxdsayonon aun wou yoaye apn siasn eyenon (2002)

150H2 oN, si9sn soyren (00% Ho pucionaig

24 010 mai 129} ‘sjonueo oyeuenes

og ue Kuo wes Us eiaaye 1uEDHIS yu ubtsap reyuousuodso-isenD siasn soyanon (2661) esnou

wew

ue Supe: won u sioay weOMIUoIS ubtsap jeqususuedee se siasn oyonon (96611661) o€sBLEIP Losiaag ‘eu8910

oy fenueisans oN, ‘sjonuee yim suojssaiboy si9sn ayanen (os61) 0m aaxnennn

‘sas hoy, ‘ABayens woneaunuepl uo si20ye seinseony siouiny ey 842R0n

‘iayonen uo Warees

uo ARUURS Fe

7

poses eu akan oc nen

i

:

346__The Efficacy of Educational Vouchers

of the program (Metcalf et al, 2003) compared the aca-

demic achievement of voucher users to two groups of

students: (1) students offered vouchers who did not use

the vouchers, and (2) a matched set of students who were

not offered vouchers. Other researchers, including Gill

al. (2001), argued that the study failed to create an

adequate control for students selfselecting into the pro-

‘gram, Belfield (2006) used a different comparison group

focusing on applicants who were rejected in their applica~

tion to privaze schools, Overall, he finds little effect on

academic achievement

‘Another key motivation for establishing the voucher

programs was ta improve students’ access to better schools

Kim Metcalf (1999) found that the program success-

fully caxgeted minorities and students from low-income

families, The mean income level of students uclizing the

vouchers was US$18 750 and these seudents were more

likely to be Aftican-American students than a random

sample of Cleveland students. As in Milwaukee, parents

‘of voucher applicants had slightly higher levels of educa-

tion (Metcalf, 1999; Peterson et al, 1999),

Other publicly funded voucher programs

Voucher programs are also in place in Vermont, Maine,

Florida, and Washington, DC. Of these programs, only

DC's Opportunity Scholarship program has any publicly

released results, which are only the first-year impacts.

‘The Institute of Education Sciences-funded evaluation

‘of Washington's program is using a randomized design

to evaluate the effectiveness of the program, ‘To date, the

results suggests chat parents are mote satisfied with the

program, but students utilizing the vouchers do not report

higher levels of satisfaction of feeling safer In addition,

text scores for these students are on par with nonvoucher

seudents (Wolfe ul, 2007). However, caution is warranted

in interpreting these results as they are noted only after

the first year of implementing the voucher program.

Domestic, Privately Funded Programs

Roman Catholic dioceses have provided scholarships to

students to attend their schools for years. The use of

philanthropists and foundation money for private school

scholarships was first popularized by J. Patrick Rooney,

sho formed the Educational Choice

1991 This trust allocated private scholarships to low-

income students to use at private schools in Indianapolis.

Other progeams in Milwaukee, Atlanta, Denver, Detroit,

Oklahoma City, and Washington, DC, soon followed.

Some of the programs were established and financed

by conservatives who wanted to either open up sectarian

school options to more students or to create competi=

tion berween private and public schools. Other programs

(eg, Oklahoma City) were funded by liberal voucher

Sharitable Trust in

nts who wanted to provide additional schooling

ities for inner-city

In 1994, the Walton Family Foundation helped create

the Children's Educational Opportunity Foundation (CEO

America) to support and create private scholarship pro-

grams, Shortly thereaites, the number of privately funded

programs quickly expanded across the country. Of these

programs, one of the most ambitious was a CEO America

program in San Anconio funded at US$S million a year for

at Jeast 10 years. The program provided fall scholarships

to over 14000 ater students making it the largest pri=

vately funded voucher program in existence at the time.

In 1998, the Walton Family Foundation helped create

the Children’s Scholarship Fund (CSF), CSP partnered

with local funders ¢o provide scholatships in cities across

the nation, In April 1999, 1.25 million low-income students

applied for 40.000 partial scholarships, Over the las decade,

more and more of the programs developed, often receiving

very little national artention, making it difficule to know

‘exacily how many of the programs currently exist.

Of these programs, CSF has received the most national

astention partially because of ts relatively large scale and

partially because CSF used randomization to asign scho-

larships. With randomization, researchers cen compare

scudents who participated in the lotteries to determine

the effectiveness of these programs, Zimmer and Bectin-

ger (2007) discuss some of the challenges in these studies.)

Other studies have been cartied out in Charloxte, Dayton,

New York, and Washington, DC among other locations

While Greene (2000) found a positive overall effect on

test scores in Charlosee after 1 year, these studies have

generally shown no effect. The one exception is among

‘Affican-American students, Howell and Peterson (2002)

and Myer ef al (2002) found that African-American stu

dents tet scores improved in New York's program. How-

fever, additional research by Krueger and Zhu (2002)

showed that this research was sensitive to the definition

of an African-American student. While the original anal-

ysis used the student's mother’s identified race for the

scudent’s race, Krueger and Zhu define African-American

seudents as those whose mother or father are identified as

African-American, This more inclusive definition results

ina scholarship effect size that is smaller than reported in

the original study and is not statistically significant

In 2 more recent study, Bettinger and Slonim (2006)

focus on the effects of vouchers on nonacademic ou

comes. Using surveys and new methods from experimen-

tal economics, they attempted to measure the effects

of the vouchers on traditional outcomes such as test scores

and on altruism, ‘To test the effects of the voucher pro-

gram on altruism, Bettinger and Slonim gave students

US$10 each and invited them to share some of their

money with charities. In this context, they show that

voucher recipients gave more to charities as a result of

the voucher program,

dents

i

:

Tho Efficacy of Educational Vouchers 347

Given that these programs were designed co target

impoverished students, it is not surprising to find that

participants have selatively low income, Peterson (1998),

for example, found tha the average income level of

families of scudents participating in the New York schal-

acship program was only USS10 000. The parenss' educa

ton level ofthe participants, however, was slightly higher

than the average level ofthe eligible population, Similarly,

Howell and Peterson (2000) and Wolf etal (2000) found

that the families of participating students were low

income. In terms of race, 100% of students participating

in the Washington, DC scholarship program were mino-

tities, while 95% of the students in New York were

minority, mostly Hispanic students. In Dayton, the per-

centage of minorities was lower bu was still 66%

Finally, these privace voucher programs cypically serve

a low percentage of special education students. For ex

ample, in New York, 9% of participating students have

disabilities compared to the district-wide average of 14%

fof special education students (Myers ef al, 2000), In

Charlotte, 4% of participating students had disabilities,

while the distict-wide average of special education stu-

dents was 11% (Greene, 2000),

International Voucher Programs

‘There are a number of educational voucher of voucher-

like programs across the world, including programs in

Chile, Colombia, Sweden, Netherlands Belize, Japan,

Canada, and Poland, These voucher programs often differ

significantly from the US programs either in terms of the

motivating factors of the policy context For example, many

of the non-US programs are motivated by the goal of

increasing school attendance among giels of low-income

students. The relationship beeween church-sponsored pri-

vate schools and public schools is also less defined in other

countries where, in many cases, religious groups operate

public schools

We focus our attention on two programs that have

figured most prominently in debates on the efficacy of

vouchers — Colombia's Programa de Ampiacion de Coberturs

de a Educacisn Secundaria (PACES) voucher program and

Chiles national voucher program,

‘Colombia PACES Program

‘The PACES offered educational vouchers to over 144000,

low-income students throughout Colombia from 1992 to

1997. The voucher program awarded full private school

tuition to secondary school students who wished co trans-

fer fom public to

secondary school. Over time, the voucher’ value did not

keep up with the cost of inflation.

Tn contrast to the US programs, the motivation for

Colombia's voucher program was to expand the capacity

vate school at the start of their

of the public school system. In Colombia, most high

school buildings host multiple high school testions per

day. Since most private schools were not overcrowded,

Colombia established the voucher program co take advan-

tage of excess capacity in the private system,

Tn cities where PACES was oversubscribed, cities held

loweries to award the vouchers, Angrise «tal (2002) use

this randomization to measure the effects of the program.

‘They find that within 3 years, voucher scudents had com-

pleted about 0.1 years of schools more than their peers

and had test scores about 0. standard deviations higher

than those who did not receive vouchers. They also find

that the incidence of child labor and teenage marriage was

lower as a result of the educational voucher. Based on

follow-up research on students’ high school careers,

Angrist et al (2006) find that voucher lottery winners

were 20% more likely to graduate from high school

than voucher lorery losers.

In Colombia, the evidence on the impacts of statifica-

tion is less developed and conclusive chan the effects on

achievement. Colombia's educational vouchers targeted

low-income families living in the poorest neighborhoods,

and Ribero and Tenjo (1997) report that the vouchers were

largely effective in reaching this population. Voucher

applicants generally came from families with higher edu-

‘cational levels than other families in the same neighbor-

hoods (Angrist of al, 2002),

Chile

In 1980, Chile embarked on an ambitious series of educa

tional reforms designed co decentralize and privatize edu-

cation. Ar the urging of Milton Friedman, who along with

other prominent economists advised the Pinochet govern

ment at the time (Rounds, 1996), Chile established per

haps the world’s largest ongoing voucher program, The

program offered tuition subsidies to private schools.

Before the reform, the budgets of public schools were

insensitive to enrolment, however, ater the reform, local

public schools last money when students tansferted to

voucher schools

Unlike Colombia, where vouchers targeted poor seu-

dents, the Chilean syscem was available to all sudents

Additionally, unlike other programs that donot allow

selective admission, voucher schools in Chile could

admit the students they most preferred. As a result of

these policies, Rounds (1996) found that the poorest

families were less likely to attend voucher schools

Research on the efficacy of Chile's voucher program

has been much more difficule co interpret than

Colombian research because of the nacure of this admis

sion policy. Some of the early evidence suggested that

voucher schools modestly outperformed public schools.

‘This finding was common in many papers (eg, Bravo

eral, 1999; McEwan and Carnoy, 2000) bu was sensitive

i

:

348 The Efficacy of Educational Vouchers

to the types of controls included in the empirical model,

the specific municipalities included in the sample, and the

statistical methods used. McEwan (2001), for example,

found that Catholic voucher schools tended to be more

effective and productive than other schools, but only for

certain specifications of the model. McEwan and Caznoy

(2000) show that academic achievement is slightly lower

in nonreligious voucher schools, particularly when

located outside the capital. Given that thar these voucher

schools have less funding, however, McEwan and Carnoy

suggest that they could still be more cost effective th

public schools

As research on the Chilean system continued, many.

researchers took note of the fact that the voucher program

akered the composition of both public and private

schools. For example, Hsieh and Urquiola (2003) showed

that more affluent families took advantage of the vou-

chets, Similar to McEwan and Carnoy (2000) and Carnoy

(2000), Hsich and Urquiola suggest that this shift in stu

lent populations could account for the finding that pri-

vate schools appear to be more effective than public

schools. In the early 1990s, many voucher schools began

charging twition in addition to the voucher, and the

difference in parents’ incomes and education levels

between these tuition-charging voucher schools and the

cther voucher schools was significant (Anand etal, 2006).

How this increased sorting across voucher and non-

voucher schools affects student achievement depends on

the nature of peer effects. If improvements in peer quality

Tead to better educational outcomes for voucher users,

then the sorting associated with the voucher program

could improve their outcomes. At the same time, given

the exit of high-quality students from the public schools,

the students left in those schools may have systematically

worse outcomes because of the

peers, The aggregate effect of the voucher depends on

the strength of these two effects

Hsieh and Urquiola (2003) argue that the only way to

idencfy the overall effects of the voucher program is (0

focus on aggregate outcomes because it is dfficuls, if noc

impossible, to remove the selection bias inherent in com-

parisons of different schools. The change in aggregate test

scores reflects both the direct achievement effects for

voucher recipients and the indirect effects for students

sho remain in public schools. When the authors look at

cchanges in aggregate test scores throughout Chile, hey

find no evidence that the voucher program increased

‘overall test scores,

Gallego (2005) provides other evidence on the Chilean

voucher program, Gallego uses an instrumental variable

approach to estimate the effects of the program. His

findings suggest positive effects of the voucher program

fon the academic outcomes of students throughout muni-

cipalities where the voucher program had more penetra-

tion, While the result may be indicative of competitive

leterioration of their

effects, it is driven in pare by the effects of the program on

voucher recipients It echoes earlier research (McEwan,

2001; McEwan and Camoy, 2000) which suggested th

voucher schools alfiliated with Catholicism had better

outcomes than other voucher schools, public of private

As McEwan and Carnoy (2000) show, Catholic schools

produced berter students ata lower cost chan other, public

or private, voucher schools,

Summary and Conclusion

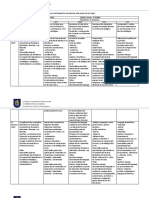

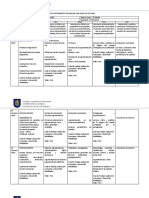

Table 1 summarizes the achievement findings from both

sic and international voucher programs. The table

highlights the location, program, methods used in the

analysis, and theit key findings

Research on domestic voucher programs has produced

inconsi sults, While advocates have often pointed

ta positive effects for Aftican-American scudents in the

CSF program as proof that vouchers can work, che

serengeh of these findings has been questioned ~ leaving

many skeptical about the purported benefits of vouchers

International studies have also found mixed results, The

dome

‘evidence from Colombia indicates that voucher users

have better academic and nonacademic outcomes than

they would have in the absence of the voucher. In Chile,

the estimated effects differ across studies, and a number of

confounding factors make it difficult to ascertain the true

‘effects. The research generally shows chat students who

take advantage of vouchers ate disadvantaged students,

‘especially in voucher programs thar are means tesced

and specifically target such students

“To date, most of the voucher sndies focus on programs

that are typically small in scale, Hence, it is not clear

whether the results generalize to large-scale programs.

For a program with massive movements of students, an

important policy consideration is not only who is partici-

pating in these programs, but what happens to the racial/

‘ethnic and ability distribution of students in public schools

In sum, researchers have failed to come to consensus

on the efficacy of vouchers as a reform effort. This murki~

ness may be clarified as new studies emerge, including

seudies of che current Milwaukee program and the feder-

ally funded Washington DC vouchers,

Future research needs to peer inside the black box

and to examine the mechanism in which outcomes dif-

fer among schools. Voucher researchers should take

the opportunity to look at private schools that may be

doing things differently and how the variation in the

operation affects outcomes. Additionally, future research

can shed additional light on the effecrs

other critical outcomes such as individual behaviors, edu

cational attainment as measured by college attendance,

and wages,

of vouchers on

i

i

i

!

‘The Efficacy of Educational Vouchers 349

Ic is also interesting to consider the value of vouchers

relative co other forms of choice. When the idea

s were first introduced, the only choices a

family could make was sending their students to private

schools without subsidies or choosing among various pub-

lic schools based on residential location. However, over

the last 50 years, a number of other alternatives have

evolved including charter schools, magnet schools, and

other inter- and intra-district choice programs. A relevant

policy question has to do with the advantages and disad-

vantages of voucher programs relative to these other

choice options, expecially when many of these choice

options are politically more feasible.

‘See a/so: Competition and Student Performance; Educa-

tional Privatization; The Economic Role of the State in

Education; The Economics of Catholic Schools; The

Economics of Parental Choice,

Bibliography

ngs J, Betinger. Bloom, €. Kemet, Mane

“ing 7002). The eect a choot vouchers on stuns

Exisenc rom Colombia, American Econom Reiow 925,

1595-7558

Anes J. Benger, ana Kremer, M2008), Long-term easton

Consequences of secondary school vouchers: evance fom

‘uinisratue recorasin Celemba, Amercan Econemie Review

9663, 847-62.

Batol C. 2. 2008, The evidonce en education voueners: AN

‘apaleation to the Cleelans senolarenp an! worng program,

epi ncspo.orgfpubleatons sles(OP112 ga accessed

shine 2003,

Botte. E. ac Slonim, R206). Using expormonta economics to

‘measre tn eee fanaa educational experiment on ara,

“Touma of Puc Economies 808-8), 1625-1648,

Bravo, D, Convers, D. anc Sanhvezs,C. (1898, Renamento

‘scala, ceuguatsd ybecha de desemnpara privsda/pubiee: Chie

"982-1997. Docunento de Taba, Desartamento de Econom’,

sso Cie, 1988,

Bearer fan maze J (2008 Tit choice andthe voucher.

Wiking Pape. Unversy of Connecticut Econemics Devarer:

(Ohute, J. and Meco. T. M1960. Potis, Market, and America's

‘Schools. Washington, DO: Brookings Istution

‘eons 5 Ean Sugrman, SD. 1978). Eoueation by Chace: The

{Case fr Famiy orto kel, CA: Univer of Calfria Press,

Epp, D. and Romano, 2. 1888). Carootionbetioon pate and

Dube senooks, vouchers and poe group eves, American

Ezaname Rene 88, 28-63

Epp ©. and Romano, A. 2009). Neghacrneed sero, chace, and

‘ne astrenuton of ecicatonal oe, n Hob, CW) The

Ezonames of Schoo! Ghoee. pp 227-286. Chicago, L: The

Unies of Cicage Poss

Fedman, Wt, 958). The cle? govemmont education. In Slo. A

ied) Beers andthe Publ terest p 122-144, Pecan,

Nu Rugors Unersy Press.

Finan, M1962), Caplaien and Freedom, Cncge, I Univer of

Chicago Press

CGallago, FA 12005), Vouchar-senal compton, canines, and

‘uteomes,Eucence tem Chl RY mimeo

GiB, Tinpane, Pt, Ross, KE, and Brower. J 700)

‘Rhetoric versus Resiy: hat Hf Krow ad What He Neos to

‘row about Youchors and Charter Schoo's. Santa Meriea, CA:

END Edueaten

‘Greene, J. (2000), The Elect of Shoe! Ghoee/n Exauaion of the

‘Gharote Chen's Scholarship Fura, New York: Cerio or Gc

Ihnovaten atthe Manhatan rai,

Creane,J.>_ Peterson, P. =, and Du, J 1007). Beciveness of Schoo!

‘Choe. The Mivaukee Experiment. Cambrcge, MA. Haars

Unoraty rogram in Eaueatom Ply and Governance

Green, JP, Person PC, an Dx, J (1988, School choice

'r Mluaukoo: A randomized experiment. Peterson, >. Ean

Hasso B.C. feds Leamng tom Schoo! Chace, op S85-358,

‘Washington. 00: Brockngs Istain,

Howe WG. and Peterson, £2000) Schoo! Choe n Dayton,

‘Ohio valiabon alr Ore Yar, Cambrage, Wie Program o9

Es.caton Pokey and Govemanco, Harvard Unversty.

Howe WG. and Patrsan >. E2002). he Education Gap: Vouchors

{ara Liban Schools. Wlashingon, DC: Boakngs ste

Helen Cana Uru, M, 2003) When soncole cornet, how co thay

‘compete? fn assossmnto! Che's natonniceschoal voucher

rogram. NBER Worn Papors 10008.

nets, C1870) Esucatoral voushars: A report on financing

‘mentary educaton ay grants ‘c parents Hep! Prepared under

(Grane CO 8549 er the U.S. Orice ef Eearame pear,

‘ashing, 20: Cone ‘r Pokey Stes.

ger fe 8. an 2h (2002). Arother Leek a he New Yor ity

‘Shoo! Yeuchor Exoarmont Wek Paper 8478, Cambie, Mi

[atonal Buren of Eeoncmic Reseach,

Le. H.2002) A comaranensie Famewk or ealusting ecuationl

‘ouster EducatonalEvatuston and Pay Arai 24), 158-174

ove (2007 seus educational pivatzaton. ad Hane

ake.) Handbook o Researen n Edveaton Pearce

arg Potcy pp 447-466, Now York Amecan Edvcation France

‘esciaton/teaum,

McEwan. Ps (2000. The potental impact of large-scale voucher

‘programs. view of Fascatona Resoareh 70, 103-128.

MeCian PJ, (2001, The etecthenese of publ, Cahole ard

‘ponolgiis ple sxnoolsn One's voucher ayer. Easton

Econamis 92) 102-128

‘McEwan Ps. [200% The potental impact vouchers. Peabody

“urna of Eucaton 798, 87-89

McEwan, and Camoy, Me (2000). The etlecveness and eficeney

‘of pate schools Gale's woucher sya, Edueatonal Evan

ana Potey Aralys 2, 213-288

Meta, KK 7909, Evasion of he Cleveland Scholae and

Tutoring Grart Program: 1995-1999, Bleringzn, IN Tre Ilana

Genter or Evaluation

Moica. K. Wes, SB Logan, Ns Paul Ke Ma aed Bo0no, Wd

"2003 Evalion of ne Clevelind seholarehip ans rng pega,

‘Sanmary Report 1998-2002, Shoringin, Nha Unveresy

School ot Fasten,

‘tgang |. D. and Cannel ©. V. 2003). Eeluctonl vouchers anc the

‘ec. Lev Mfc) Prvating Educator: Can he

Marketplace Delvor Ghote, Ener, Equty, ard Social Cohesion?

bp 20-38. Sauer, CO: Wessew.

Myers, Peterson. Mayer, D., C204 J, and Howell WG. 2000

‘School hoicein New Yar iy ater Two Yeas: An Evaluation of he

‘Scheo! Groce Schaar Program. Washegton, OC: Mathematics

Potey Research

‘Myers0.P, Person... Miers, D.E. Ttle,C.C. ancHowel. WG.

1200). Sihecl choba intew Vor Cry ater tee yours. Anevaaion

‘ofthe schol choos scholarps progam. Rep. No. 8404-045,

Pancoton, Nu thera Phy Reserch.

[Nechyba, T2000. Moby, ageing a rate school vouchers.

“imorcan Econemic Rie 80, 730-146

Peterson, P.E (198). An Evaluation ofthe New York ty School

‘Shoe Scholwshiog Program: The Fst Year. Cambriage. MA

Progam on Eascaon Ploy and Governance, Harare Unser

Peterson. P., Howe W., and Groene JP (1999).An Featation

ofthe Clovoland Voucher Progra afte Tv Yeas. Catrige. MA

Program on Eoveaton Poly and Governance Hanara Un,

‘ibe, Rand Tena, (1997), Unversty de los Andes, Daparment ot

Econemios Wering Paper.

Pounds, P."-(1996) Wi pursut of Nigher quslysacrite equal

‘opperuy mn eduation? An anak fhe educatianal voucher

system fy Santago, Sci Slonee Guaron) 77s, 825-845,

ipo, Pun, Ali sed

350__ The Efficacy of Educational Vouchers

rouse, Cx, 1988), Pras school vouchare and student achievement

"revaluation of he Mila.koo pavovtlchace progr. Qoarteny

‘loumal of Economics 143, 952-802,

\Wesconan Legiabve Aut Sureau WNLAB) (200). Miwaukeo Parental

‘Shove Progam: An Evauston. Madison, Wi Legilatve Aut

Buea.

ite, JF. {996). Who bene from he Miva choice program?

Flo, @., mcr, AF, aed Ore. ous) Who Chooses, Whe

Loosee? Cute, nstitene, andthe Unequal Etect of Schoo!

{Ghoice, po 118-187. New Vere Toacrors College Press.

ite F. 2000). The Maret Aperoach fo Eeucabon Pnceton, Nb

Princeton Universi Press

ite JF ana Thom, CA 1886. Who chooses? Vouchor and

intr chole programs in Wiiaukes, American Joatal of

Easton 104, 187-217.

Will P, Gutman, B., Pura. Mf. lzo, Land ssa N (2007,

valistonof.0. cppertinty sohatrshi progres pacts ste

‘ono yar ratte ol Eaueaton Seance, US Deparment o!

Eaueaton NEE 2007-4009,

Wo P, Howl, WG, and Patrson, .E, 2000, Schoo!

‘Ghoie in Washington D.C. An Essuatan afer Che Year.

‘Gamorage, MA. Program on Educaton Pay and Govemance,

Harare Univer

Zeer, Hand Bette, E (2007. Bayer hereto:

Surveying he evence cf vouchers and tax eects. Lads, H. ard

see ds Handbook of Research Faveaton Finance and

ley. pp 447-266, New Yorke Amercan Edacation France

‘Aesociatonvetoaum,

Further Reading

‘ele, 0. A. and Westen .L (2008, Eoatinal tax ced for

‘rmoia's school, NOSPE Paley Brot 3. phwanesce.crgl

ublctons les/P808.fccessed Jane 2008,

Bertnger, F. Kremer, W. and Saavedra, 2008) How eduestenal

ouner aloe! sliders the ree ol vocalona ign senooks

Colombia, Case Vester Resere ries,

‘cornay, M. (1808, National yousna Glan n Chil and Sweden ie

‘vata sare make fr beter ecueston? Carpets

Edveaten Review 8219, 309-537

CCoeran, J Hr Ta Kine, 8. (1882 Cognitive

‘uleeres in pub and pate schocls, Sociology of Education

55.65.76,

vans, WN. ane Sehwag, P1895) Finishing highschool ane sath

‘lege: Do Cathal shcoke make a dterence? Quarry Joumal of

cones 1208), 881-974,

Fao, ©, and Lucia, J (2000) Sex, drugs ant Oatrote chooks:

Privat schol rd non-maraladolescon| behaves, NBER

Working Paper No. 7990, Noverbor 2000.

Ca Band Bosker, K. 2007, Sencl competion and studs

fouleomas, In Lad H.F an Pace 8 ods) Handbook of

Research Eduction Finance and Poy, po 185-702. Now York

‘rraran Caveaton Finance Mesecalen/=Hoaum,

‘Groone, JP. and Hal, 12007). The GEO Herzen Scholashio

Progtam: A Case Siua’of School Vouchers inthe Edged

Inagpendect Schoo Distt, San Anton, Washingon, D>

Natheraea Peley Resear,

Howe WS, (2008, Dynamic selon eects n mear-tested, ban

‘Schoo veer progres, vounal of Pley Anas and

Management 282}, 225-250.

king, Ratlngs,L. Guar, M. Pars, ©. and Tones, © (1897,

"Colombia's targeted educaten voucher rogram: Features

‘covrage and parson. oka Pape No.3, Sais an Ire

Essien o Eaveaton Anvorms, Ooveloomon! Esanomice

Fesoaren Group, The Wits Bank

Lad HLF. anc Hansen, J 8. ed 1098. Making Maney ater:

rancing Amenca's Schoo. Washes, DO: Naonal Acacery

Press.

oun Hi 1988). Cluctonl voucher: lectveness, choles, and

‘cost, veumal of Polcy Arabi and Management 17}, 372-392

Lenn H (1809) The publinpevate nexus fh ecucaton. American

ehavcal Scents 48), 124-137

Peterson. PE. Camobel,0.£, and West, M.R. 2001). Ae Evaluation

‘ofthe Basie Fund Seholrship rogram the San Farsco Bay

‘rea, Calor, Cambri, MA: Program on Education Poly and

overnanen

Torr, .F (1096, Publ funding and orate schootng acoss

‘Saintes lou ofa and Fecramice 88, "21-148,

Relevant Websites

hepsi tvookngs edu —Brockngs Ist,

heb /tece‘ern sem ~ Carr fr Ecucaton Reform.

psi ecweaiorg ~ Eduesion Week

‘pnt racaesoundton org ~Fredran Fourdston fer

cational rae,

tp 2wen8a.r9— National Education Associaton

‘rept ncape.o9 ~ National entero the Sty of ration in

Fovsaton,

‘sep vancerlt.ed— Varderis Nsonl Centar on Scho

‘Shove,

También podría gustarte

- LYLSM21E3MDocumento322 páginasLYLSM21E3MFornachiari67% (3)

- (Basil Bernstein) Poder, Educación y ConcienciaDocumento163 páginas(Basil Bernstein) Poder, Educación y ConcienciaUk mats100% (1)

- 2 BasicoDocumento3 páginas2 BasicoRó StroskoskovichAún no hay calificaciones

- 4 MedioDocumento4 páginas4 MedioRó StroskoskovichAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 MedioDocumento5 páginas1 MedioRó StroskoskovichAún no hay calificaciones

- 3 MedioDocumento4 páginas3 MedioRó StroskoskovichAún no hay calificaciones

- Lenguaje para NacionalDocumento125 páginasLenguaje para NacionalRó StroskoskovichAún no hay calificaciones

- Sintetizar Idea CentralDocumento3 páginasSintetizar Idea CentralRó StroskoskovichAún no hay calificaciones

- 4° Medio - Evaluación Diagnostica PSU - 1° SemestreDocumento9 páginas4° Medio - Evaluación Diagnostica PSU - 1° SemestreCAROLINA BEATRIZ HIDALGO ARRIAGADAAún no hay calificaciones

- Sistema de MemoriaDocumento15 páginasSistema de MemoriaRó StroskoskovichAún no hay calificaciones

- Lenguaje Priorizacion PDFDocumento51 páginasLenguaje Priorizacion PDFMaría Ignacia GonzálezAún no hay calificaciones

- RecursosversussimceDocumento18 páginasRecursosversussimceClaudia Antonia Zepeda LedezmaAún no hay calificaciones

- Lectura Estratgica Colaborativa PDFDocumento114 páginasLectura Estratgica Colaborativa PDFInés de TroyaAún no hay calificaciones

- Camino Al Bicentenario. Propuestas para Chile 2007 PDFDocumento374 páginasCamino Al Bicentenario. Propuestas para Chile 2007 PDFPablo Castillo VeraAún no hay calificaciones

- Sistema Chile Solidario y La Politica de Proteccion Social en Chile Dagmar RaczynskiDocumento52 páginasSistema Chile Solidario y La Politica de Proteccion Social en Chile Dagmar RaczynskiKaren Hernández PetrónAún no hay calificaciones

- Matriz de IndicadoresDocumento73 páginasMatriz de IndicadorescsarioneAún no hay calificaciones

- Lenguaje y Comunicación 3º Medio - Texto Del EstudianteDocumento322 páginasLenguaje y Comunicación 3º Medio - Texto Del EstudianteAndrés Alegría AravenaAún no hay calificaciones

- Calendar I oDocumento9 páginasCalendar I oRó StroskoskovichAún no hay calificaciones

- Articles-141020 Informe FinalDocumento148 páginasArticles-141020 Informe FinalDayakAún no hay calificaciones

- Art 6Documento17 páginasArt 6Lahuán FreireAún no hay calificaciones

- Desarrollo Local en ChileDocumento0 páginasDesarrollo Local en ChileDaniel EduardoAún no hay calificaciones

- (I) Temarios Modalidad Flexible 2018Documento5 páginas(I) Temarios Modalidad Flexible 2018Ró StroskoskovichAún no hay calificaciones

- (I) Temarios Validación de Estudios 2018Documento4 páginas(I) Temarios Validación de Estudios 2018Ró StroskoskovichAún no hay calificaciones

- Articles 31611 PDFDocumento159 páginasArticles 31611 PDF1nerak1Aún no hay calificaciones

- Art 25Documento14 páginasArt 25Cristian MolinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Aplicabilidad de Adecuaciones Curriculares A Ninos Con SuperdotacionDocumento106 páginasAplicabilidad de Adecuaciones Curriculares A Ninos Con SuperdotacionRó StroskoskovichAún no hay calificaciones

- Marco LogicoDocumento3 páginasMarco LogicomirakgenAún no hay calificaciones

- (I) Informe Tareas Contigo Aprendo (2017)Documento4 páginas(I) Informe Tareas Contigo Aprendo (2017)Ró StroskoskovichAún no hay calificaciones

- (I) ITE FlexibleDocumento9 páginas(I) ITE FlexibleRó StroskoskovichAún no hay calificaciones

- (I) Educación Básica RegularDocumento21 páginas(I) Educación Básica RegularRó StroskoskovichAún no hay calificaciones