Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 12 - Ex Officio Investigation - PP 431-434

Cargado por

AtlasOfTortureDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 12 - Ex Officio Investigation - PP 431-434

Cargado por

AtlasOfTortureCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

OX FOR D C OM M E N TA R I E S ON

I N T E R N AT ION A L L AW

General Editors: Professor Philip Alston, Professor of International Law

at New York University, and Professor Vaughan Lowe, Chichele Professor

of Public International Law in the University of Oxford and Fellow of

All Souls College, Oxford.

The United Nations Convention

Against Torture

A Commentary

00-Nowak-Prelims.indd i 7/10/2007 7:50:32 AM

00-Nowak-Prelims.indd ii 7/10/2007 7:50:33 AM

The United Nations

Convention Against

Torture

A Commentary

M A N FR E D NOWA K

E L I Z A BE T H Mc A RT H U R

with the contribution of

Kerstin Buchinger

Julia Kozma

Roland Schmidt

Isabelle Tschan

Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Human Rights Vienna

00-Nowak-Prelims.indd iii 7/10/2007 7:50:33 AM

Article 12. Ex Officio Investigations 431

4. Issues of Interpretation

4.1 Meaning of ‘reasonable ground to believe’

49 As was stated above,⁵⁶ there are ample opportunities to find a ‘reason-

able ground’ to believe that an act of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading

treatment has been committed. Apart from a complaint by the victim, a fellow

detainee might have witnessed or even only heard of a torture practice, lawyers,

doctors, nurses or family members of detainees, NGOs or national human

rights commissions might be invited to report frankly about every single case

of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment which was brought to

their attention. The most efficient way to find out whether and to what extent

torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment is practised in any given

country is to ratify the OP, establish a truly independent national preventive

mechanism (NPM) which regularly carries out unannounced visits to every

place of detention and which conducts private interviews with detainees, and

to request this body either to investigate on its own every single allegation of

torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or to bring such allega-

tions to another independent authority competent to proceed to a prompt and

impartial investigation. A government genuinely interested in knowing the

truth might also open up its detention facilities to unannounced visits by com-

petent NGOs or invite the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture to carry out a

fact finding mission in full compliance with his terms of reference.

50 The main diff erence between Articles 13 and 12 is that the latter shifts the

responsibility to initiate an investigation from the victim to the State authorities

most directly involved. Since torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treat-

ment usually takes place behind closed doors without any outside witnesses,

and since the victims are often too afraid to complain officially about such

practices, the heads of police stations, interrogation offices, pre-trial detention

facilities and prisons have a particular responsibility to prevent torture. One of

the most efficient ways to prevent torture is actively to monitor and investigate

the situation in the respective detention facility and to take the necessary dis-

ciplinary or other action in every single case of ill-treatment or excessive use of

force. If torture occurs in a given detention facility, and its head is not aware

of such practices or fails to take the necessary preventive measures, he or she

might be held accountable for committing the crime of torture by consent or

acquiescence.

⁵⁶ See above, 1.

14-Nowak-Chap12.indd 431 7/9/2007 1:37:27 PM

432 United Nations Convention Against Torture

51 One of the most effective measures to prevent torture and cruel, inhu-

man or degrading treatment is a thorough and independent medical examina-

tion of every detainee when arriving at a particular detention facility, when

leaving this facility and at any other time, in particular at his or her own

request. If a person arrives healthy at a police station and leaves the same police

station two days later with certain bruises or injuries, this is a ‘reasonable

ground’ to believe that an act of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treat-

ment has been committed and the burden of proof shifts to the police officers

responsible for the detention and interrogation.⁵⁷ Whether the injuries were

self-inflicted or the result of a legitimate use of force by the respective police

officers or the result of ill-treatment needs to be established by a prompt and

impartial investigation before an independent body.

52 Often, detainees do not dare to report torture and ill-treatment while

being held at the place where this treatment occurred. As soon as they are

transferred from the police or criminal investigation station to a pre-trial

detention centre, they might wish to lodge a complaint. For a torture victim to

speak about his or her traumatic experience it is necessary to create conditions

where the victim feels safe from reprisals and trustful that his or her allegations

are taken seriously. Again, the best person to talk to might be the doctor who

carries out a medical examination upon arrival.⁵⁸ Not surprisingly, torture

victims do not immediately start to speak openly. Often, the initiative must

come from the doctor. When detecting a recent scar or injury during a routine

examination, it is up to the doctor to ask where the scar or injury came from.

If the explanation given by the detainee is not convincing, there is ‘reasonable

ground’ to proceed to a more thorough investigation.

53 The Committee repeatedly stressed the obligation of States parties to

investigate detailed allegations from national and international NGOs⁵⁹ and

the fact that the decision on whether to conduct an investigation is not discre-

tionary.⁶⁰ If there are reasonable grounds, an investigation must be instigated

regardless of the origin of suspicion.⁶¹ In the leading case of Blanco Abad v.

Spain,⁶² the Committee found a violation of Article 12 on the ground that

the High Court had not started an investigation despite having before it five

⁵⁷ See also the European Court of Human Rights case of Ribitsch v. Austria (1996) 21 EHRR

573.

⁵⁸ See also the facts in Blanco Abad v. Spain, Comm. No. 59/1996. See above, 3.2.

⁵⁹ See e.g. A/57/44, § 5(i) and the facts in M’Barek v. Tunisia, No. 60/1996, above, 3.2.

⁶⁰ See e.g. CAT/C/SR.145, §10 and SR.168, § 40. See also the concluding observations on the

third periodic report of France, CAT/C/FRA/CO/3, § 20.

⁶¹ No. 59/1996, § 8.2. See above, 3.2

⁶² Ibid, § 8.2. See above, 3.2.

14-Nowak-Chap12.indd 432 7/9/2007 1:37:27 PM

Article 12. Ex Officio Investigations 433

reports of a forensic physician which noted that she had ‘complained of hav-

ing been subjected to ill-treatment consisting of insults, threats and blows,

of having been kept hooded for many hours and of having been forced to

remain naked, although she displayed no signs of violence. The Committee

considers that these elements should have sufficed for the initiation of an

investigation, which did not however take place.’⁶³ In the Roma pogrom case

of Dzemajl et al. v. Yugoslavia, the Committee found a violation of Article 12

on the ground that, despite the presence of a number of police officers both

at the time and at the scene of the pogrom, no proper investigations had been

initiated and no person nor any member of the police forces had been tried

by the courts.⁶⁴ In Thabti v. Tunisia, the Committee confirmed its earlier

jurisprudence and noted that Article 12 places an obligation on the authori-

ties to ‘proceed automatically’ to a prompt and impartial investigation whenever

there are reasonable grounds to believe that an act of torture or ill-treatment

has been committed, ‘no special importance being attached to the grounds

for suspicion’.⁶⁵

54 In its concluding observations after having examined the second peri-

odic report of the United States, the Committee in May 2006 interpreted the

provision of Article 12 to require the US authorities ‘to promptly, thoroughly

and impartially investigate any responsibility of senior military and civilian

officials authorizing, acquiescing or consenting in any way, to acts of torture

committed by their subordinates’.⁶⁶ Since most of the controversial interro-

gation methods used in Guantánamo Bay, Abu Ghraib and similar detention

centres for suspected terrorists were explicitly authorized by Defense Secretary

Donald Rumsfeld,⁶⁷ it seems evident that his particular responsibility should

be subject of such an independent investigation required by Article 12.

4.2 Meaning of ‘prompt investigation’

55 In the case of a suspicion of torture or ill-treatment, a prompt investiga-

tion is of particular importance. First of all, the victim might be in danger of

further torture. A prompt official investigation by the head of the respective

detention centre or an external monitoring body might prevent further torture,

above all as a means of reprisal. Secondly, the physical traces of torture and ill-

⁶³ Ibid, § 8.3.

⁶⁴ No. 161/2000, § 9.4. See above, 3.2.

⁶⁵ No. 187/2001, § 10.4. See above, 3.2.

⁶⁶ CAT/C/USA/CO/2, § 19.

⁶⁷ See e.g. the report of five special procedures on the situation of detainees at Guantánamo Bay

detention facilities, E/CN.4/2006/120; see also Nowak, (2006) 28(4) HRQ 809–841.

14-Nowak-Chap12.indd 433 7/9/2007 1:37:27 PM

434 United Nations Convention Against Torture

treatment, if any, might soon disappear.⁶⁸ The obligation under Article 12 to

proceed to a prompt investigation, therefore, means that as soon as there is a

suspicion of a case of torture or ill-treatment, investigations shall be initiated

immediately or without any delay, i.e. within the next hours or days.⁶⁹

56 In most cases in which the Committee found a violation of Article 12, no

investigations had been carried out at all or only after long periods. In Halimi-

Nedyibi v. Austria, the Committee found that a delay of 15 months before any

investigation into the allegations of torture and ill-treatment had started was

‘unreasonably long’ and therefore a violation of the requirement of a prompt

investigation as laid down in Article 12.⁷⁰ In M’Barek v. Tunisia, it held that a

delay of over ten months ‘after the foreign non-governmental organization had

raised the alarm and over two months after the Driss Commission’s report’ was

excessive and, therefore constituted a violation of Article 12.⁷¹

57 The only case in which a considerably shorter period of delay, namely

some two weeks, was held to constitute a violation of Article 12, is the well-

known case of Blanco Abad v. Spain which concerns ill-treatment by officers

of the Guardia Civil between 29 January and 2 February 1992, where the

complainant had been kept incommunicado under anti-terrorist legislation.⁷²

Signs of her ill-treatment were noticed by a doctor at a Women’s Penitentiary

Centre who had examined her upon arrival on 3 February 1992. The prison

director, in complying with the relevant obligations under Articles 12 and 13,

immediately brought the physician’s report to the attention of the competent

judge. The Committee observed that ‘when, on 3 February, the physician of

the penitentiary centre noted bruises and contusions on the author’s body, this

fact was brought to the attention of the judicial authorities. However, the com-

petent judge did not take up the matter until 17 February and Court No. 44

initiated preliminary proceedings only on 21 February.’⁷³ This delay was held

to be ‘incompatible with the obligation to proceed to a prompt investigation,

as provided for in article 12 of the Convention’.⁷⁴ This finding clearly confirms

the interpretation that a prompt investigation, in order to be effective, must be

initiated within hours or, at the most, a few days after the suspicion of torture

or ill-treatment has arisen.

⁶⁸ Cf. Wendland, 52.

⁶⁹ This corresponds also to the meaning of ‘promptly’ in Arts. 9 and 14 CCPR: cf. Nowak,

CCPR-Commentary, 210–240, 302–357.

⁷⁰ No. 8/1991, § 15. See above, 3.2.

⁷¹ No. 60/1996, §§ 11.5–11.7. See above, 3.2.

⁷² No. 59/1996; see above, 3.2.

⁷³ Ibid, § 8.4.

⁷⁴ Ibid, § 8.5.

14-Nowak-Chap12.indd 434 7/9/2007 1:37:27 PM

También podría gustarte

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2099)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (73)

- Outsourcing Strategies ChallengesDocumento21 páginasOutsourcing Strategies ChallengesshivenderAún no hay calificaciones

- Barbri Notes Personal JurisdictionDocumento28 páginasBarbri Notes Personal Jurisdictionaconklin20100% (1)

- Cinema and Human Rights - Media LiteracyDocumento27 páginasCinema and Human Rights - Media LiteracyAtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- Petritsch - European ParliamentDocumento7 páginasPetritsch - European ParliamentAtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- Cinema and Human Rights - Media LiteracyDocumento27 páginasCinema and Human Rights - Media LiteracyAtlasOfTorture100% (1)

- Petritsch - Federal Court - Ait IdirDocumento4 páginasPetritsch - Federal Court - Ait IdirAtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- Media Literacy IDocumento1 páginaMedia Literacy IAtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - OPCAT Article 18 - Independence Pluralism Efficiency - PP .1074 - 1076Documento6 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - OPCAT Article 18 - Independence Pluralism Efficiency - PP .1074 - 1076AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- Style SheetDocumento5 páginasStyle SheetAtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- Info Note On Academic Writing and Formal RequirementsDocumento4 páginasInfo Note On Academic Writing and Formal RequirementsAtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - OPCAT Article 4 - Obligation To Allow Preventive Visits - PP 931-934Documento7 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - OPCAT Article 4 - Obligation To Allow Preventive Visits - PP 931-934AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- CHR Distribution of MoviesDocumento1 páginaCHR Distribution of MoviesAtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - OPCAT Article 19 - Mandate and Power of NPM - PP .1080 - 1083Documento7 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - OPCAT Article 19 - Mandate and Power of NPM - PP .1080 - 1083AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - OPCAT Article 20 - Obligation of State Parties To Facilitate Visits - PP 1088-1091Documento7 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - OPCAT Article 20 - Obligation of State Parties To Facilitate Visits - PP 1088-1091AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - OPCAT Article 3 - Establishment of NPM - PP 922-924Documento6 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - OPCAT Article 3 - Establishment of NPM - PP 922-924AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 14 - Right of Victims To Adequate Remedy - PP 492 - 496Documento8 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 14 - Right of Victims To Adequate Remedy - PP 492 - 496AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 15 - Non-Admissibility of Evidence - PP 530-534Documento8 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 15 - Non-Admissibility of Evidence - PP 530-534AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 16 - CIDT - PP 557-558Documento5 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 16 - CIDT - PP 557-558AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 2 - Obligation To Prevent Torture (Absolute Prohibition) - PP 117-121Documento8 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 2 - Obligation To Prevent Torture (Absolute Prohibition) - PP 117-121AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 14 - Right of Victims To Adequate Remedy - PP 481 - 483Documento6 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 14 - Right of Victims To Adequate Remedy - PP 481 - 483AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 5 - Types of Jurisdiction Over Torture - PP 317-321Documento8 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 5 - Types of Jurisdiction Over Torture - PP 317-321AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 7 - Aut Dedere Aut Iudicare - PP 363-367Documento8 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 7 - Aut Dedere Aut Iudicare - PP 363-367AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 13 - Right To Complain - PP 448-451Documento7 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 13 - Right To Complain - PP 448-451AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 1 - Definition of Torture - PP 72-73Documento5 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 1 - Definition of Torture - PP 72-73AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 1 - Definition of Torture - PP 66-69Documento7 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 1 - Definition of Torture - PP 66-69AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 7 - Aut Dedere Aut Iudicare - PP 359-360Documento5 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 7 - Aut Dedere Aut Iudicare - PP 359-360AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 4 - Obligation To Criminalize Torture - PP 247-251Documento8 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 4 - Obligation To Criminalize Torture - PP 247-251AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- OUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 3 - Principle of Non-Refoulement - PP 206-210Documento8 páginasOUP CAT Commentary - Extract - Article 3 - Principle of Non-Refoulement - PP 206-210AtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- CAT Commentary - Combined ExtractsDocumento77 páginasCAT Commentary - Combined ExtractsAtlasOfTortureAún no hay calificaciones

- WW 3Documento12 páginasWW 3ayesha ziaAún no hay calificaciones

- Love Is FleetingDocumento1 páginaLove Is FleetingAnanya RayAún no hay calificaciones

- Crash Course 34Documento3 páginasCrash Course 34Gurmani RAún no hay calificaciones

- Borders Negative CaseDocumento161 páginasBorders Negative CaseJulioacg98Aún no hay calificaciones

- Foundation Course ProjectDocumento10 páginasFoundation Course ProjectKiran MauryaAún no hay calificaciones

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Psy4324.501.11f Taught by Salena Brody (smb051000)Documento7 páginasUT Dallas Syllabus For Psy4324.501.11f Taught by Salena Brody (smb051000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupAún no hay calificaciones

- Erd.2.f.008 Sworn AffidavitDocumento2 páginasErd.2.f.008 Sworn Affidavitblueberry712Aún no hay calificaciones

- Contemporary Latino MediaDocumento358 páginasContemporary Latino MediaDavid González TolosaAún no hay calificaciones

- Eng PDFDocumento256 páginasEng PDFCarmen RodriguezAún no hay calificaciones

- Belgrade Insight - February 2011.Documento9 páginasBelgrade Insight - February 2011.Dragana DjermanovicAún no hay calificaciones

- 860600-Identifying Modes of CirculationDocumento7 páginas860600-Identifying Modes of CirculationericAún no hay calificaciones

- Page2Documento1 páginaPage2The Myanmar TimesAún no hay calificaciones

- Justice and FairnessDocumento35 páginasJustice and FairnessRichard Dan Ilao ReyesAún no hay calificaciones

- 1392 5105 2 PB PDFDocumento7 páginas1392 5105 2 PB PDFNunuAún no hay calificaciones

- Critical Meme AnalysisDocumento6 páginasCritical Meme Analysisapi-337716184Aún no hay calificaciones

- Hindu Code BillDocumento2 páginasHindu Code BillSathwickBorugaddaAún no hay calificaciones

- Week 7 MAT101Documento28 páginasWeek 7 MAT101Rexsielyn BarquerosAún no hay calificaciones

- C6 - Request For Citizenship by Marriage - v1.1 - FillableDocumento9 páginasC6 - Request For Citizenship by Marriage - v1.1 - Fillableleslie010Aún no hay calificaciones

- Iowa State U.A.W. PAC - 6084 - DR1Documento2 páginasIowa State U.A.W. PAC - 6084 - DR1Zach EdwardsAún no hay calificaciones

- Research EssayDocumento29 páginasResearch Essayapi-247831139Aún no hay calificaciones

- Honorata Jakubowska, Dominik Antonowicz, Radoslaw Kossakowski - Female Fans, Gender Relations and Football Fandom-Routledge (2020)Documento236 páginasHonorata Jakubowska, Dominik Antonowicz, Radoslaw Kossakowski - Female Fans, Gender Relations and Football Fandom-Routledge (2020)marianaencarnacao00Aún no hay calificaciones

- Apush Chapter 19Documento6 páginasApush Chapter 19api-237316331Aún no hay calificaciones

- International and Regional Legal Framework for Protecting Displaced Women and GirlsDocumento32 páginasInternational and Regional Legal Framework for Protecting Displaced Women and Girlschanlwin2007Aún no hay calificaciones

- Marxism and NationalismDocumento22 páginasMarxism and NationalismKenan Koçak100% (1)

- State of Sutton - A Borough of ContradictionsDocumento158 páginasState of Sutton - A Borough of ContradictionsPaul ScullyAún no hay calificaciones

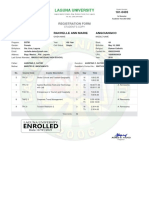

- Laguna University: Registration FormDocumento1 páginaLaguna University: Registration FormMonica EspinosaAún no hay calificaciones

- Residents Free Days Balboa ParkDocumento1 páginaResidents Free Days Balboa ParkmarcelaAún no hay calificaciones

- Ari The Conversations Series 1 Ambassador Zhong JianhuaDocumento16 páginasAri The Conversations Series 1 Ambassador Zhong Jianhuaapi-232523826Aún no hay calificaciones