Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

PRINT EO 459 and 1969 Vienna Summary

Cargado por

Rina TruDescripción original:

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

PRINT EO 459 and 1969 Vienna Summary

Cargado por

Rina TruCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

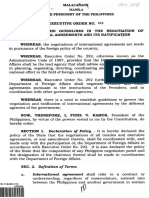

EXECUTIVE ORDER NO.

459

EXECUTIVE ORDER NO. 459 - PROVIDING FOR THE GUIDELINES IN

THE NEGOTIATION OF INTERNATIONAL AGREEMENTS AND ITS

RATIFICATION

WHEREAS, the negotiations of international agreements are made in

pursuance of the foreign policy of the country;

WHEREAS, Executive Order No. 292, otherwise known as the

Administrative Code of 1987, provides that the Department of Foreign

Affairs shall be the lead agency that shall advise and assist the

President in planning, organizing, directing, coordinating and

evaluating the total national effort in the field of foreign relations;

WHEREAS, Executive Order No. 292 further provides that the

Department of Foreign Affairs shall negotiate treaties and other

agreements pursuant to the instructions of the President, and in

coordination with other government agencies;

WHEREAS, there is a need to establish guidelines to govern the

negotiation and ratification of international agreements by the

different agencies of the government;

NOW, THEREFORE, I, FIDEL V. RAMOS, President of the Philippines,

by virtue of the powers vested in me by the Constitution, do hereby

order:

Section 1. Declaration of Policy. — It is hereby declared the policy of

the State that the negotiations of all treaties and executive

agreements, or any amendment thereto, shall be coordinated with,

and made only with the participation of, the Department of Foreign

Affairs in accordance with Executive Order No. 292. It is also declared

the policy of the State that the composition of any Philippine

negotiation panel and the designation of the chairman thereof shall be

made in coordination with the Department of Foreign Affairs.

Sec. 2. Definition of Terms. —

a. International agreement — shall refer to a contract or

understanding, regardless of nomenclature, entered into between the

Philippines and another government in written form and governed by

international law, whether embodied in a single instrument or in two

or more related instruments.

b. Treaties — international agreements entered into by the Philippines

which require legislative concurrence after executive ratification. This

term may include compacts like conventions, declarations, covenants

and acts.

c. Executive Agreements — similar to treaties except that they do not

require legislative concurrence.

d. Full Powers — authority granted by a Head of State or Government

to a delegation head enabling the latter to bind his country to the

commitments made in the negotiations to be pursued.

e. National Interest — advantage or enhanced prestige or benefit to

the country as defined by its political and/or administrative

leadership.

f. Provisional Effect — recognition by one or both sides of the

negotiation process that an agreement be considered in force

pending compliance with domestic requirements for the effectivity of

the agreement.

Sec. 3. Authority to Negotiate. — Prior to any international meeting or

negotiation of a treaty or executive agreement, authorization must be

secured by the lead agency from the President through the Secretary of

Foreign Affairs. The request for authorization shall be in writing, proposing

the composition of the Philippine delegation and recommending the range

of positions to be taken by that delegation. In case of negotiations of

agreements, changes of national policy or those involving international

arrangements of a permanent character entered into in the name of the

Government of the Republic of the Philippines, the authorization shall be in

the form of Full Powers and formal instructions. In cases of other

agreements, a written authorization from the President shall be sufficient.

Sec. 4. Full Powers. — The issuance of Full Powers shall be made by the

President of the Philippines who may delegate this function to the

Secretary of Foreign Affairs.

The following persons, however, shall not require Full Powers prior to

negotiating or signing a treaty or an executive agreement, or any

amendment thereto, by virtue of the nature of their functions:

a. Secretary of Foreign Affairs;

b. Heads of Philippine diplomatic missions, for the purpose of

adopting the text of a treaty or an agreement between the Philippines

and the State to which they are accredited;

c. Representatives accredited by the Philippines to an international

conference or to an international organization or one of its organs, for

the purpose of adopting the text of a treaty in that conference,

organization or organ.

Sec. 5. Negotiations. —

a. In cases involving negotiations of agreements, the composition of

the Philippine panel or delegation shall be determined by the

President upon the recommendation of the Secretary of Foreign

Affairs and the lead agency if it is not the Department of Foreign

Affairs.

b. The lead agency in the negotiation of a treaty or an executive

agreement, or any amendment thereto, shall convene a meeting of the

panel members prior to the commencement of any negotiations for

the purpose of establishing the parameters of the negotiating position

of the panel. No deviation from the agreed parameters shall be made

without prior consultations with the members of the negotiating

panel.

Sec. 6. Entry into Force and Provisional Application of Treaties and

Executive Agreements. —

a. A treaty or an executive agreement enters into force upon

compliance with the domestic requirements stated in this Order.

b. No treaty or executive agreement shall be given provisional effect

unless it is shown that a pressing national interest will be upheld

thereby. The Department of Foreign Affairs, in consultation with the

concerned agencies, shall determine whether a treaty or an executive

agreement, or any amendment thereto, shall be given provisional

effect.

Sec. 7. Domestic Requirements for the Entry into Force of a Treaty or an

Executive Agreement. — The domestic requirements for the entry into

force of a treaty or an executive agreement, or any amendment thereto,

shall be as follows:

A. Executive Agreements.

i. All executive agreements shall be transmitted to the Department of

Foreign Affairs after their signing for the preparation of the ratification

papers. The transmittal shall include the highlights of the agreements

and the benefits which will accrue to the Philippines arising from

them.

ii. The Department of Foreign Affairs, pursuant to the endorsement by

the concerned agency, shall transmit the agreements to the President

of the Philippines for his ratification. The original signed instrument

of ratification shall then be returned to the Department of Foreign

Affairs for appropriate action.

B. Treaties.

i. All treaties, regardless of their designation, shall comply with the

requirements provided in sub-paragraph 1 and 2, item A (Executive

Agreements) of this Section. In addition, the Department of Foreign

Affairs shall submit the treaties to the Senate of the Philippines for

concurrence in the ratification by the President. A certified true copy

of the treaties, in such numbers as may be required by the Senate,

together with a certified true copy of the ratification instrument, shall

accompany the submission of the treaties to the Senate.

ii. Upon receipt of the concurrence by the Senate, the Department of

Foreign Affairs shall comply with the provision of the treaties in

effecting their entry into force.

Sec. 8. Notice to Concerned Agencies. — The Department of Foreign

Affairs shall inform the concerned agencies of the entry into force of the

agreement.

Sec. 9. Determination of the Nature of the Agreement. — The Department

of Foreign Affairs shall determine whether an agreement is an executive

agreement or a treaty.

Sec. 10. Separability Clause. — If, for any reason, any part or provision of

this Order shall be held unconstitutional or invalid, other parts or provisions

hereof which are not affected thereby shall continue to be in full force and

effect.

Sec. 11. Repealing Clause. — All executive orders, proclamations,

memorandum orders or memorandum circulars inconsistent herewith are

hereby repealed or modified accordingly.

Sec. 12. Effectivity. — This Executive Order shall take effect immediately

upon its approval.

DONE in the City of Manila, this 25th day of November in the year of Our

Lord, Nineteen Hundred and Ninety-Seven.

Historical Context

By the middle of the twentieth century the

customary international law of treaties had

grown to a fairly comprehensive body of rules. In

view of that, the International Law Commission

placed it at its first session, in 1949, among the

topics suitable for codification and appointed

James Brierly as Special Rapporteur. He resigned in 1952 and two of his

successors, Sir Hersch Lauterpacht and Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice, each of

whom had started the work anew, the second moreover with a different

approach, were elected to the International Court of Justice before they

could finish their work. The last Special Rapporteur, Sir Humphrey

Waldock, appointed in 1961, oriented the work again towards the

preparation of draft articles capable of serving as a basis for an

international convention. His six reports enabled the Commission in 1966 to

submit a final draft to the General Assembly and to recommend that the

Assembly convene an international conference to conclude a convention

on the subject. By resolution 2166 (XXI) of 5 December 1966, the General

Assembly endorsed the recommendation in principle and in the following

year decided to convene the first session of the conference in 1968 and the

second session in 1969, in Vienna.

Significant Points in the Negotiating History

The United Nations Conference on the Law of Treaties was the last great

codification conference that successfully used voting as its working method

and could adopt the draft articles by substantial majorities. The final text of

the convention was accepted by 79 votes to 1, with 19 abstentions. This

achievement was helped by two circumstances. On the one hand, the

customary law covering the more technical side of treaty-making was,

except for minor details, practically undisputed. In respect of the potentially

more controversial chapter concerning the termination of treaties, on the

other hand, many States had achieved a moderate position by balancing, in

view of unknown future eventualities, the wish to escape a treaty obligation

against the wish to have it kept.

Summary of Key Provisions

Article 1 restricts the application of the Convention to (written) treaties

between States, excluding treaties concluded by international

organizations. In other respects, the first four parts of the Convention codify

previously existing customary law with a few modifications due to

progressive development.

A conspicuous example of the latter is reservations. The Convention

follows the Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice

on Reservations to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of

the Crime of Genocide (I.C. J. Reports 1951, p. 15) and prohibits

reservations which are incompatible with the object and purpose of the

treaty to which they relate (article 19 (c)). But the provision does not clarify

the status of a reservation that infringes the prohibition, which gives rise to

conflicting interpretations of the effect of objections made to such

reservations. A related problem arises from the definition of a reservation

(article 2, paragraph 1 (d)) which seems to imply that reservations must

indicate the provision or provisions to which they relate (“…to exclude or to

modify the legal effect of certain provisions”, emphasis added), which

raises doubts about the admissibility of so-called “across-the-board-

reservations” (i.e. reservations which make the implementation of treaty

obligations subject to their compatibility with domestic or some religious

law) without providing a conclusive answer. Both controversial issues are

now under study by the International Law Commission under the topic

“Reservations to treaties”.

Another result of progressive development is the rule of interpretation in

article 31, which establishes, inter alia, the object and purpose of a treaty

and the latter’s context as guidelines of interpretation. These are

teleological elements which militate against a narrow literal construction of

treaty texts. It is noteworthy that the International Court of Justice stated in

the Judgment on theArbitral Award of 31 July 1989 that “…[a]rticles 31 and

32 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties…may in many

respects be considered as a codification of existing customary international

law…” (I.C.J. Reports 1991, pp. 69-70, para. 48). Yet, it is not clear

whether the Court was of the opinion that the custom had

existed before the Vienna Convention and had been codified in it, or that it

had been generated by it and was by now “existing”.

Part V of the Convention deals with the invalidity, termination and

suspension of the operation of treaties. It is the key part of the Convention.

The relevant customary rules had evolved from isolated instances of State

practice or unconnected arbitral or judicial pronouncements. It was the

International Law Commission that gave this incoherent material a

systematic structure.

The grounds of invalidity of treaties or termination are either taken from

among the general principles of law (error, fraud), or adapt these to

situations particular to international law, like the corruption of a

representative (article 50), or the coercion of a representative (article 51),

or of a State by the threat or use of force (article 52). The most far-reaching

development of the law was the introduction of the concept of jus

cogens into positive international law in articles 53 and 64. It has become

relevant outside the scope of the law of treaties as a major element in the

construction of modern international law.

The procedure for asserting one of the grounds of invalidity or

termination has gained recognition in practice beyond the Convention since

this part of customary law had been most lacking in precision. The

International Court of Justice observed in the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros

Project case in this respect: “…[a]rticles 65 to 67 of the Vienna Convention

on the Law of Treaties, if not codifying customary law, at least generally

reflect customary international law and contain certain procedural principles

which are based on an obligation to act in good faith” ( I.C.J. Reports 1997,

p. 66, para. 109).

Article 66, which provides for the judicial settlement, arbitration or

conciliation of disputes arising from the application of the rules in Part V of

the Convention, establishes in subparagraph (a) the mandatory jurisdiction

of the International Court of Justice in disputes involving jus cogens, unless

the parties agree to submit the dispute to arbitration. This unique feature,

which was not proposed by the International Law Commission but

originated in the Conference, is motivated by the intention to concentrate

the jurisdiction over such disputes in a single organ in order to avoid the

fragmentation of jus cogens by competing jurisdictions. The adoption of the

“package deal” (A/CONF. 39/L. 47/Rev.1), which contained, inter alia, the

jurisdictional clause, by 61 votes against 20, with 26 abstentions in plenary

was, nonetheless, only secured by the great prestige of the leader of the

Nigerian delegation to the Conference and Chairman of its Committee of

the Whole, Taslim O. Elias (later Judge and President of the International

Court of Justice), who was the moving spirit behind the package deal. The

package deal also included a declaration inviting the General Assembly of

the United Nations to consider issuing invitations under article 81 of the

Vienna Convention to States not members of the United Nations, the

specialized agencies or parties to the Statute of the International Court of

Justice to become parties to the Convention so as to ensure the widest

possible participation. The declaration was an attempt to satisfy the

socialist States which, at the time, tried to obtain admission to international

conferences and multilateral treaties for the (then) German Democratic

Republic, and had pursued that aim unsuccessfully throughout the Vienna

Conference against the opposition of the Federal Republic of Germany,

backed by the West. Although the attempt to insert a formula providing for

universal participation in the Convention was not successful, and the

socialist States had voted also against the package deal because they

objected to its other part, the jurisdictional clause, the declaration may

nevertheless have allowed them to abstain from voting against the adoption

of the Convention as a whole and thus secured a convincing majority

(many abstaining States have in the meantime acceded to the Vienna

Convention, among them the Russian Federation on 29 April 1986).

However, as might be expected, article 66, or at least its subparagraph

(a) became the subject of reservations, mainly by (former) socialist States,

some of which have in the meantime been withdrawn. Other States

objected to such reservations and excluded in response the application of

articles of the Convention which were inextricably linked to the jurisdictional

clause (i.e., provisions in Part V to which the procedural provisions relate)

in relations between them and the reserving States. Determining the

applicable provisions and the appropriate jurisdiction in a relevant case

may thus be rather complicated, and it should be noted that until now no

case involving a treaty that allegedly conflicted with a peremptory norm of

international law has been brought before the International Court of Justice.

Influence of the Instrument on Subsequent Developments

The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties is in force since 27

January 1980 and has 108 parties (as of 15 December 2008). The

International Court of Justice has in several cases referred to it without

examining whether the litigants were parties to the Convention. In

the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros Project case the Court observed: “[The Court]

needs only to be mindful of the fact that it has several times had occasion

to hold that some of the rules laid down in that Convention might be

considered as a codification of existing customary law” (I.C.J. Reports

1997, p. 38, para. 46). The Court’s opinion, together with the relatively high

number of parties to the Convention, suggests that the instrument states

the current general international law of treaties. This is also confirmed by

the fact that its substantive provisions were by consensus copied into the

1986 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties between States and

International Organizations or between International Organizations.

Related Materials

A. Jurisprudence

International Court of Justice, Reservations to the Convention on

Genocide, Advisory Opinion: I.C.J. Reports 1951, p. 15.

International Court of Justice, Arbitral Award of 31 July 1989 (Guinea-

Bissau v. Senegal), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1991, p. 53.

International Court of Justice, The Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros Project

(Hungary/Slovakia), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1997, p. 7.

B. Documents

Report of the International Law Commission on the work of its first session,

12 April 1949 (A/CN.4/12 and Corr. 1-3, reproduced in Yearbook of the

International Law Commission, 1949, vol. I, Part One, Chapter II).

Report of the International Law Commission on the work of its eighteenth

session, 4 May - 19 July 1966 (A/CN.4/191, reproduced in Yearbook of the

International Law Commission, 1966, vol. I, Part One, Chapter II).

General Assembly resolution 2166 (XXI) of 5 December 1966 (International

conference of plenipotentiaries on the law of treaties).

Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Nigeria, Sudan,

Tunisia and the United Republic of Tanzania: draft declaration, proposed

new article and draft resolution (A/CONF. 39/L. 47/Rev.1, reproduced

in United Nations Conference on the Law of Treaties, First and second

sessions, Vienna, 26 March-24 May 1968 and 9 April-22 May 1969, Official

Records, Documents of the Conference, p. 272).

C. Doctrine

A. Aust, Modern Treaty Law and Practice, Cambridge, Cambridge

University Press, 2000.

E. Castrén, “La Convention de Vienne sur le droit des traités”, in: R.

Marcic et al. (eds.),Internationale Festschrift für Alfred Verdross zum 80.

Geburtstag, München/Salzburg, Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 1971, pp. 71-83.

T. O. Elias, The Modern Law of Treaties, New York, Oceana-Sijthoff, 1974.

A. McNair, Law of Treaties, 2nd ed., Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1961.

P. Reuter, La Convention de Vienne du 23 mai 1969 sur le droit des traités,

Paris, Armand Collin, 1970.

P. Reuter, Introduction au droit des traités, Paris, Armand Collin, 1972 ;

réédition Presses Universitaires de France 1985.

S. Rosenne, The Law of treaties, Leyden, Sijthoff, 1970.

I . Sinclair, The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 2nd ed.

Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1984.

E. Vierdag, “The International Court of Justice and the Law of Treaties”, in:

V. Lowe & M Fitzmaurice (eds.), Fifty Years of the International Court of

Justice, 1996, pp. 145-196.

M. E. Villiger, Commentary on the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of

Treaties, Netherlands, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2009.

R.G. Wetzel & D. Rauschning, The Vienna Convention on the Law of

Treaties. Travaux Preparatoires, Frankfurt am Main, Alfred Metzner Verlag,

1978.

También podría gustarte

- Torts and Damages Case DigestsDocumento3 páginasTorts and Damages Case DigestslchieSAún no hay calificaciones

- LIP ReviewerDocumento31 páginasLIP Reviewermitsudayo_Aún no hay calificaciones

- Corpo Midterms Memory AidDocumento5 páginasCorpo Midterms Memory AidfrancessantosAún no hay calificaciones

- Abakada Guro Party ListDocumento1 páginaAbakada Guro Party ListLaw SSCAún no hay calificaciones

- Lchong v. Hernandez, G.R. No. L-7995, May 31, 1957Documento22 páginasLchong v. Hernandez, G.R. No. L-7995, May 31, 1957AkiNiHandiongAún no hay calificaciones

- CEMCO v. National LifeDocumento4 páginasCEMCO v. National LifeChedeng KumaAún no hay calificaciones

- Admin DigestsDocumento6 páginasAdmin DigestsXavier Alexen AseronAún no hay calificaciones

- William C. Reagan V CIR (1969)Documento1 páginaWilliam C. Reagan V CIR (1969)Hezekiah JoshuaAún no hay calificaciones

- Admin Elect Public CorpDocumento27 páginasAdmin Elect Public CorpJohn Ramil RabeAún no hay calificaciones

- Public International ATTY.EDocumento842 páginasPublic International ATTY.EKarlaColinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Taxation Law - Case Digest (Part 2)Documento2 páginasTaxation Law - Case Digest (Part 2)MiroAún no hay calificaciones

- Public Corp Finals Reviewer (Pup)Documento42 páginasPublic Corp Finals Reviewer (Pup)Don So HiongAún no hay calificaciones

- 04-08.surigao Mineral Reservation Board v. CloribelDocumento15 páginas04-08.surigao Mineral Reservation Board v. CloribelOdette JumaoasAún no hay calificaciones

- Gonzales vs. Abaya Crim 2Documento3 páginasGonzales vs. Abaya Crim 2sakuraAún no hay calificaciones

- 1.B CalalasDocumento1 página1.B CalalasWhere Did Macky GallegoAún no hay calificaciones

- Reviewer TaxDocumento52 páginasReviewer TaxRogelio Saguinsin IIIAún no hay calificaciones

- Philippine Administrative Law, p.42Documento27 páginasPhilippine Administrative Law, p.42Dax CalamayaAún no hay calificaciones

- Topacio vs. OngDocumento4 páginasTopacio vs. OngLaura MangantulaoAún no hay calificaciones

- Tirol.2011 2015.bar - QuestionsDocumento167 páginasTirol.2011 2015.bar - QuestionsMark Jason S. TirolAún no hay calificaciones

- Rule 19 - InterventionDocumento5 páginasRule 19 - InterventionJereca Ubando JubaAún no hay calificaciones

- Partnership and Corporation by de LeonDocumento2 páginasPartnership and Corporation by de LeonblahblahblueAún no hay calificaciones

- Intellectual Property Law Case SummariesDocumento13 páginasIntellectual Property Law Case SummariesHARing iBONAún no hay calificaciones

- Transpo Cases Maritime Air Transpo Et AlDocumento3 páginasTranspo Cases Maritime Air Transpo Et AlMae MaihtAún no hay calificaciones

- DIGEST - Republic v. CFI ManilaDocumento2 páginasDIGEST - Republic v. CFI ManilaAgatha ApolinarioAún no hay calificaciones

- Criminal Law 1: Chapter 1: FeloniesDocumento3 páginasCriminal Law 1: Chapter 1: FeloniesGerolyn Del PilarAún no hay calificaciones

- The Registry of PropertyDocumento2 páginasThe Registry of PropertyChem MaeAún no hay calificaciones

- Detective Vs CloribelDocumento2 páginasDetective Vs CloribelAllenMarkLuperaAún no hay calificaciones

- 34-Tuazon v. Heirs of Bartolome Ramos G.R. No. 156262 July 14, 2005Documento4 páginas34-Tuazon v. Heirs of Bartolome Ramos G.R. No. 156262 July 14, 2005Jopan SJAún no hay calificaciones

- 97 GV FLORIDA Vs TIARA COMMERCIAL PDFDocumento1 página97 GV FLORIDA Vs TIARA COMMERCIAL PDFTon Ton CananeaAún no hay calificaciones

- Jurisdiction of Cta Enbanc and DivisionDocumento12 páginasJurisdiction of Cta Enbanc and DivisionJune Karl CepidaAún no hay calificaciones

- Authority To Act, at Their Own Initiative or Upon Request of Either or Both Parties, On All Inter-Union and IntraDocumento4 páginasAuthority To Act, at Their Own Initiative or Upon Request of Either or Both Parties, On All Inter-Union and IntraMunchie MichieAún no hay calificaciones

- Republic Act 9285Documento19 páginasRepublic Act 9285Devee Mae VillaminAún no hay calificaciones

- Tax 1 PrimerDocumento113 páginasTax 1 PrimerBirthday NanamanAún no hay calificaciones

- La Naval Drug Corp Vs CADocumento2 páginasLa Naval Drug Corp Vs CAUE LawAún no hay calificaciones

- 3.) OCA-Circular-No.156-2006 (Authority of COC To Notarize Documents)Documento1 página3.) OCA-Circular-No.156-2006 (Authority of COC To Notarize Documents)Kriezl Nierra JadulcoAún no hay calificaciones

- Pale Case Digest Batch 2 2019 2020Documento26 páginasPale Case Digest Batch 2 2019 2020Carmii HoAún no hay calificaciones

- Table 1: Reliefs in Case of Termination Without Prior NoticeDocumento6 páginasTable 1: Reliefs in Case of Termination Without Prior NoticeMer CeeAún no hay calificaciones

- Human Rights NotesDocumento5 páginasHuman Rights NotesJay GeeAún no hay calificaciones

- Bus Org 1 Partnership CasesDocumento9 páginasBus Org 1 Partnership CasesAerwin AbesamisAún no hay calificaciones

- Manila Memorial Park v. Secretary of DSWDDocumento2 páginasManila Memorial Park v. Secretary of DSWDcorky01Aún no hay calificaciones

- Union Motor Corporation Vs CADocumento7 páginasUnion Motor Corporation Vs CAJillian BatacAún no hay calificaciones

- Commercial Law Review Cases Batch 2Documento42 páginasCommercial Law Review Cases Batch 2KarmaranthAún no hay calificaciones

- Lesson 2 TaxationDocumento25 páginasLesson 2 TaxationGracielle EspirituAún no hay calificaciones

- Review of The Movie - Liar Liar Vishnu BC0150035Documento7 páginasReview of The Movie - Liar Liar Vishnu BC0150035vishnu PAún no hay calificaciones

- Labor Law Review Assignment CBA 2017Documento2 páginasLabor Law Review Assignment CBA 2017KM MacAún no hay calificaciones

- G.R. No. 185894, August 30, 2017Documento25 páginasG.R. No. 185894, August 30, 2017SheAún no hay calificaciones

- Gokongwei Jr. v. SECDocumento6 páginasGokongwei Jr. v. SECspringchicken88Aún no hay calificaciones

- Natural Resources Activity 2 (Group 1 JD2A)Documento67 páginasNatural Resources Activity 2 (Group 1 JD2A)MerabSalio-anAún no hay calificaciones

- Cabanlig vs. SB - Self DefenseDocumento11 páginasCabanlig vs. SB - Self DefensehlcameroAún no hay calificaciones

- Comparison of The Rules On Evidence (07.05.2020) - v2 FinalDocumento44 páginasComparison of The Rules On Evidence (07.05.2020) - v2 FinalConcerned CitizenAún no hay calificaciones

- Ycain Vs Caneja2Documento2 páginasYcain Vs Caneja2Ruby IlajiAún no hay calificaciones

- Civpro Midterms 2Documento27 páginasCivpro Midterms 2Carina Amor ClaveriaAún no hay calificaciones

- PSPCA v. COADocumento2 páginasPSPCA v. COALian LopezAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Digest in COLDocumento42 páginasCase Digest in COLDominic M. CerbitoAún no hay calificaciones

- Final Exam Civ LawDocumento6 páginasFinal Exam Civ LawBass TēhAún no hay calificaciones

- Supreme Court: The Solicitor General For Plaintiff-Appellee. Wenceslao I. Ponferrada III For Accused-AppellantDocumento10 páginasSupreme Court: The Solicitor General For Plaintiff-Appellee. Wenceslao I. Ponferrada III For Accused-AppellantAngelReaAún no hay calificaciones

- Corpo DigestDocumento6 páginasCorpo DigestAlan MakasiarAún no hay calificaciones

- The New Philippine Skylanders, Inc. Vs Francisco DakilaDocumento1 páginaThe New Philippine Skylanders, Inc. Vs Francisco DakilaRosana Villordon SoliteAún no hay calificaciones

- Eo 459 1997Documento5 páginasEo 459 1997davidAún no hay calificaciones

- Position Paper-SDocumento10 páginasPosition Paper-SRina TruAún no hay calificaciones

- History of Corporations From The Earliest Times Up To The PresentDocumento24 páginasHistory of Corporations From The Earliest Times Up To The PresentRina TruAún no hay calificaciones

- Position PaperDocumento6 páginasPosition PaperRina TruAún no hay calificaciones

- Respondents' Position Paper: ComplainantsDocumento16 páginasRespondents' Position Paper: ComplainantsRina TruAún no hay calificaciones

- Significant Changes and IntroductionsDocumento6 páginasSignificant Changes and IntroductionsRina TruAún no hay calificaciones

- 2 Marcos vs. Manglapus, G.R. No. 88211 September 15, 1989Documento32 páginas2 Marcos vs. Manglapus, G.R. No. 88211 September 15, 1989Rina TruAún no hay calificaciones

- Corporation vs. Partnership and Sole Proprietorship: DistinctionDocumento20 páginasCorporation vs. Partnership and Sole Proprietorship: DistinctionRina TruAún no hay calificaciones

- History and Development of Corporations: Philippine SettingDocumento7 páginasHistory and Development of Corporations: Philippine SettingRina TruAún no hay calificaciones

- CIA UAV - Unmanned Aerial Vehicles UN IHL: AbbreviationDocumento3 páginasCIA UAV - Unmanned Aerial Vehicles UN IHL: AbbreviationRina TruAún no hay calificaciones

- Labrel Feb 1Documento24 páginasLabrel Feb 1Rina TruAún no hay calificaciones

- IPPTChap 003Documento97 páginasIPPTChap 003Rina TruAún no hay calificaciones

- 5Documento118 páginas5Rina TruAún no hay calificaciones

- Ureg QF 02Documento1 páginaUreg QF 02Rina TruAún no hay calificaciones

- Sustainable Development and GeopoliticsDocumento18 páginasSustainable Development and GeopoliticsAnn Sharmain DeGuzman StaRosaAún no hay calificaciones

- Yogi Ahir 2020Documento4 páginasYogi Ahir 2020Issac JohnAún no hay calificaciones

- Arts 10 Quarter 3 Week 7 Las # 1Documento2 páginasArts 10 Quarter 3 Week 7 Las # 1ariel velaAún no hay calificaciones

- Functions of Art and PhilosophyDocumento5 páginasFunctions of Art and PhilosophyQuibong, Genard G.Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Talent Code: Greatness Isn't Born. It's Grown. Here's How. - Daniel CoyleDocumento5 páginasThe Talent Code: Greatness Isn't Born. It's Grown. Here's How. - Daniel Coylemupukuju23% (13)

- Adarsh Tripathi Constitutional Law ProjectDocumento30 páginasAdarsh Tripathi Constitutional Law Projectshekhar singhAún no hay calificaciones

- MAPEH 10 Q4 Week 4Documento8 páginasMAPEH 10 Q4 Week 4John Andy Abarca0% (1)

- Corporate Governance TuteDocumento14 páginasCorporate Governance TutebuddikalrAún no hay calificaciones

- 13th Asia Pacific Harmonica Festival RegistrationDocumento22 páginas13th Asia Pacific Harmonica Festival Registrationapi-61899779Aún no hay calificaciones

- Moral Recovery LetterDocumento2 páginasMoral Recovery LetterNovaAún no hay calificaciones

- Charts & Publications: Recommended Retail Prices (UK RRP)Documento3 páginasCharts & Publications: Recommended Retail Prices (UK RRP)KishanKashyapAún no hay calificaciones

- Important FAQsDocumento8 páginasImportant FAQsAli KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Annotated BibDocumento6 páginasAnnotated BibMelody Nichole RodriguezAún no hay calificaciones

- Budgeting The Educational PlanDocumento5 páginasBudgeting The Educational Plancameracafe90% (21)

- Aviation Maintenance ManagementDocumento5 páginasAviation Maintenance ManagementSiddharth Sawhney100% (1)

- 40 Supreme Court Reports Annotated: People vs. OperoDocumento7 páginas40 Supreme Court Reports Annotated: People vs. OperoJanicaAún no hay calificaciones

- ProjectDocumento18 páginasProjectDigvijay Singh100% (4)

- Articulo en Ingles Sobre Recursos HumanosDocumento5 páginasArticulo en Ingles Sobre Recursos HumanosLUZAún no hay calificaciones

- Instructor - Dr. Preeti Khanna (Only For Academic Purpose)Documento23 páginasInstructor - Dr. Preeti Khanna (Only For Academic Purpose)MOHAMMED AMIN SHAIKHAún no hay calificaciones

- The Union of Southwest Airlines Flight Attendants TWU Local 556Documento2 páginasThe Union of Southwest Airlines Flight Attendants TWU Local 556SaraAún no hay calificaciones

- eduroam-US Best Practices GuideDocumento9 páginaseduroam-US Best Practices GuideiwjvbbqzAún no hay calificaciones

- Curriculum DevelopmentDocumento12 páginasCurriculum DevelopmentDa dang100% (6)

- Puraniks City Neral - BrochureDocumento9 páginasPuraniks City Neral - BrochurePuranik BuildersAún no hay calificaciones

- BSEB STET2019 General InstructionsDocumento2 páginasBSEB STET2019 General InstructionsRahul SankrityaayanAún no hay calificaciones

- Next Generation Internet of Things Distributed Intelligence at The Edge IERC 2018 Cluster Ebook 978-87-7022-007-1 P WebDocumento352 páginasNext Generation Internet of Things Distributed Intelligence at The Edge IERC 2018 Cluster Ebook 978-87-7022-007-1 P WebcbcaribeAún no hay calificaciones

- 16 Early Signs of Autismx16 Months ChecklistDocumento1 página16 Early Signs of Autismx16 Months ChecklistGtd Cdis CcsnAún no hay calificaciones

- Comparitive Study of Recruitment AdsDocumento9 páginasComparitive Study of Recruitment Adsvenkataswamynath channaAún no hay calificaciones

- Lesson Plan-Inquiry Subtraction Regrouping 1Documento11 páginasLesson Plan-Inquiry Subtraction Regrouping 1api-529737133Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Poetpreneur by Olumide Holloway Aka King OluluDocumento92 páginasThe Poetpreneur by Olumide Holloway Aka King OluluOlumide HollowayAún no hay calificaciones

- Guide New Zealand Cattle FarmingDocumento144 páginasGuide New Zealand Cattle Farmingjohn pierreAún no hay calificaciones