Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Untitled

Cargado por

outdash20 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

290 vistas10 páginasThe term "human dignity" is used in a lot of different contexts. The main discussion about kavod habriyos involves cases where following halacha will place someone in an embarrassing situation. The TSA has introduced new policies regarding screening passengers.

Descripción original:

Derechos de autor

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponibles

DOC, PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoThe term "human dignity" is used in a lot of different contexts. The main discussion about kavod habriyos involves cases where following halacha will place someone in an embarrassing situation. The TSA has introduced new policies regarding screening passengers.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como DOC, PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

290 vistas10 páginasUntitled

Cargado por

outdash2The term "human dignity" is used in a lot of different contexts. The main discussion about kavod habriyos involves cases where following halacha will place someone in an embarrassing situation. The TSA has introduced new policies regarding screening passengers.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como DOC, PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

Está en la página 1de 10

Full Body Scanners,

Enhanced Pat-downs

and the role of Kavod

HaBriyos

By Rabbi Joshua Flug

For technical information regarding use of

.this document, press ctrl and click here

I. Introduction-

a. The term "human dignity" is used in a lot of different contexts. Some may argue for

human dignity in an end of life issue. Some might argue for human dignity in

treating prisoners properly and refraining from enhanced interrogation methods. The

list goes on and on. We have a term called kavod habriyos which can be loosely

translated as human dignity. The main discussion about kavod habriyos in the

Gemara involves cases where following halacha will place someone in an

embarrassing situation. For example, someone is walking in the public domain and

he realized that the only clothing he has on contains sha'atnez. Should kavod

habriyos be a factor in allowing this person to continue to wear the garment until he

can get to a location where he can comfortably change his clothing?

b. In recent weeks, the TSA has introduced new policies regarding screening

passengers. Depending on the airport, certain passengers are asked to enter a full

body scanner that allows a screener to see through one's clothes and detect any

incendiary devices one might be carrying. The screener actually sees a nude image of

the body. The passenger can opt out of a full body scan and receive an enhanced pat

down from a TSA agent. Many reports from passengers indicate that both the full

body scan and the enhanced pat down can be very intrusive and embarrassing. How

should one balance kavod habriyos and public safety?

c. R. Chaim Shmulevitz (1902-1979) has a mussar schmooze about kavod habriyos

where he provides a number of examples of acts of kavod habriyos in cases where

one would think that the person doesn't deserve kavod (e.g. Bilam). He notes that the

fact that the Gemara entertains violating all halacha to protect human dignity teaches

us the importance of kavod habriyos and the greatness of man. It is only because we

don't properly understand the greatness of man that we don't properly fulfill our

mandate of kavod habriyos. {} [Click here to access to entire sicha.]

II. The Role of Kavod haBriyos in Exempting one From Halachic Obligations

a. The Gemara states that if one is walking in the public domain and he realized that the

only clothing he has on contains sha'atnez, he must remove it immediately because

nothing can stand in the way of the Torah. {}

i. R. Elazar Azikri (Sefer Chareidim 1533-1600) writes that kavod habriyos (or

what the Yerushalmi calls kavod harabim) is a rabbinic mitzvah and therefore,

one cannot violate negative commandments to fulfill kavod habriyos. {}

ii. R. Yosef Teomim (P'ri Megadim 1727-1793) writes that kavod habriyos is a

biblical mitzvah. Yet, it still does not allow one to violate negative

commandments. {}

b. The Gemara states that although one cannot actively violate a Torah commandment to

protect human dignity, one can passively violate a commandment. {}

i. There is an important dispute among the Rishonim regarding this rule.

1. Rambam (1138-1204) is of the opinion that if one sees another person

wearing sha'atnez, he must rip the clothing off of the other individual.

{}

2. Rabbeinu Asher (c. 1250-1327) disagrees and maintains that one only

has to remove one's own clothing. However, if informing someone

else about a violation will cause embarrassment, it is better to wait to

inform them in a private location. {}

3. R. Yechezkel Landa (1713-1793) suggests that the dispute between

Rambam and Rabbeinu Asher might be relevant to other situations

where informing someone about a violation will cause embarrassment,

such as the case of informing a husband that his wife had an affair. {}

ii. R. Elchanan Wasserman (1874-1941) presents two ways to understand why

one can passively allow a violation to happen when it conflicts with kavod

habriyos: {}

1. There is a conflict between the mitzvah and kavod habriyos and

therefore, the best solution is to remain passive. One cannot actively

violate a transgression, but one is not obligated to embarrass oneself in

order to actively fulfill a mitzvah. If one assumes this approach, the

critical factor is the method of violation or lack thereof that determines

when kavod habriyos trumps a mitzvah.

2. Failure to fulfill a mitzvah is not as severe as violation of a

transgression. Therefore, kavod habriyos trumps obligations to fulfill

mitzvos but not violations. According to this approach, the critical

factor is the severity of the violation.

c. The Gemara states that one can violate rabbinic prohibitions if it interferes with

kavod habriyos. {}

i. Rashi (1040-1105) implies that the reason why kavod habriyos trumps

rabbinic laws is that the rabbis never intended that their institutions should

cause someone embarrassment. Therefore, the gezeirah or takanah does not

apply. {}

ii. R. Avraham Erlanger (Maggid Shiur at Kol HaTorah) writes that one can

alternatively understand that there is an override of the rabbinic law when it

comes in conflict with kavod habriyos. He relates this to the question of

whether it is hutrah or dechuyah. {}

iii. There are times when poskim have been reluctant to allow kavod habriyos to

override a rabbinic law:

1. R. Ya'akov Yisrael Kanievski (the Steipler Rav 1899-1985) discusses

the permissibility of shaking hands with a member of the opposite sex.

The questioner suggested that perhaps it should be permissible to

avoid embarrassment given that shaking hands is only a rabbinic

prohibition. The Steipler responded that kavod habriyos is only

applicable when must choose between two results, neither of which are

beneficial. Regarding shaking hands, the concern is that one will

desire the touch of the handshake and benefit from it. Therefore,

kavod habriyos cannot override the prohibition. {}

2. R. Moshe Feinstein (1895-1986) discusses the minhag of a husband

and wife refraining from passing items to one another while she is a

niddah. R. Moshe asserts that kavod habriyos is not a valid claim

because there is nothing to be embarrassed about. {}

III. Actively Embarrassing Someone for a Purpose

a. The Gemara derives from the story of Yehuda and Tamar that it is preferable to allow

oneself to be killed rather than embarrass someone publicly. Tamar had the

opportunity to vindicate herself by stating that she was impregnated by Yehuda.

However, instead she was prepared to have herself killed if Yehuda was not willing to

admit that he was the owner of the collateral that she took. {}

i. Tosafos ask: If embarrassing someone is יהרג ואל יעברwhy isn't this on the list

of aveiros chamuros? Tosafos answer that the list only includes prohibitions

that are explicit in the Torah. Tosafos' answer implies that in fact,

embarrassing someone is יהרג ואל יעבר. {}

ii. Rabbeinu Yonah (d. 1263) writes that it is יהרג ואל יעברbecause it is אבזרייהו

דרציחה. Just as activities that relate to arayos are יהרג ואל יעבר, even if one

does not violate actual arayos, the same applies to publicly embarrassing

someone, which is a form of retzicha. {}

iii. R. Menachem Meiri (1249-1306) writes that the Gemara was not meant to be

taken literally and the rabbis are merely stressing the severity of embarrassing

someone. {}

b. R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach (1910-1995) asks: if public embarrassment is equivalent

to murder, why don't we consider saving someone from embarrassment to be pikuach

nefesh and allow violation of Shabbos or other Torah law? He answers that even if

one assumes that one cannot embarrass someone else to save a life, that doesn't mean

that it is pikuach nefesh. Rather, saving a life is bound by certain rules and according

to Tosafos and Rabbeinu Yonah, embarrassing someone is not a valid means of

saving a life. Yet, because the individual doesn't actually die from embarrassment,

one cannot violate Torah law to save a life. Even rabbinic law is limited by the rules

of kavod habriyos [which does not allow someone to violate rabbinic law to prevent

another individual from embarrassing someone publicly.] {}

i. R. Shlomo Zalman highlights an important distinction between causing a

situation of embarrassment and getting out of an embarrassing situation.

Causing embarrassment is very severe and according to some Rishonim,

should not even be employed to save a life. Getting out of an embarrassing

situation is the discussion in the Gemara about kavod habriyos.

c. Rambam writes that when rebuking someone, the first attempts should try to

minimize embarrassment as much as possible. If that does not work, one may even

embarrass the individual publicly for bein adam LaMakom violations. {}

i. R. Yosef Babad (1801-1874, Minchas Chinuch) suggests that there is no real

distinction between bein adam LaMakom and bein adam lachaveiro. Rambam

is merely stating the victim himself may not embarrass the violator as rebuke

for the violation. {}

ii. How is it possible that it is permissible to embarrass someone just to give

someone rebuke? Meiri writes that it is based on the principle in the Mishna

that embarrassment is contingent on intent to embarrass. {} When one intends

to rebuke and not embarrass, it is not as severe and the mitzvah of tochachah

overrides the prohibition. Meiri notes that one must be careful in determining

that the act is done for altruistic reasons. {}

iii. R. Avraham D. Wahrman (of Buchatch 1770-1840) suggests that there is no

prohibition against embarrassing someone if there is no intent to embarrass.

Even if the person was mistaken and embarrassed accidentally, the victim has

no claim against the "violator." {}

IV. Applications to Original Discussion

a. Kavod HaBriyos serves as an exemption from passive violations as well as rabbinic

laws. In both scenarios, the severity of public embarrassment may play a role.

b. The question of what mechanism is used to ignore rabbinic law is an important public

policy question.

i. If the rabbis didn't include it in the original gezeirah, this implies that in

theory, that have the right to do so in situations of need.

ii. If kavod habriyos is an override, it is possible that the rabbis cannot create an

institution that interferes with kavod habriyos.

iii. R. Naftali Z.Y. Berlin (The Netziv 1816-1893) writes that we do find a case

where the rabbis specifically instituted something knowing that it will affect

kavod habriyos. The case is burial on Yom Tov Sheni Shel Galuyos. The

rules of kavod habriyos (which Netziv applies to kavod hameis) should dictate

that one should be allowed to violate the rabbinically mandated holiday to

bury a corpse. However, because of the concern for denigrating Yom Tov

Sheni, the rabbis specifically allowed for the discretion to prohibit burial on

Yom Tov Sheni. This is true despite the kavod habriyos factor.{}

c. Public embarrassment is severe enough so that it as least arguable that one should not

embarrass people, even if the purpose is to protect them from danger. [I.e. one should

not use overly invasive procedures, even if it is to prevent a terrorist attack.]

d. Nevertheless, when one is conducting an activity that has an embarrassing outcome, it

is not the same as specifically intending to embarrass someone. Therefore, it is

arguable (based on Meiri and R. Wahrman) that the government has the right to

institute policies that might cause embarrassment since the purpose is to protect not to

embarrass.

.5ברכות יט-:כ. .1שיחת מוסר תשל"ב מאמר לו

נמצינו למדים עד כמה גדול כבוד הבריות,

מגדול שבגדולים על הפחות שבפחותים,

וגופי תורה נדחים מפניו ,וכל כך למה?

ונראה שיסוד חומר כבוד הבריות וגדולתו

הוא משום שהאדם עצמו גדול מאד ולכן

כבודו חמור כל כך ,אלא שאנו אין לנו

השגה בגדלות האדם ,ולכן אנו תמהים על

כך.

.2ברכות יט:

.6רמב"ם הל' כלאים י:כט

.3פירוש החרדים לירושלמי ג:א

.4שושנת העמקים ריש כלל ו'

.7רא"ש הלכות כלאי בגדים אות ו'

.8שו"ת נודע ביהודה או"ח א:לה

.12ברכת אברהם שבת צד. .9קובץ ביאורים גיטין אות כו

.13קריינא דאגרתא עמ' קעח

.10ברכות יט:

.11רש"י ברכות יט:

.18בית הבחירה סוטה י: .14אגרות משה יו"ד ב:עז

.19מנחת שלמה א:ז

.15בבא מציעא נט.

.16סוטה י:

.20רמב"ם הל' דעות ו:ח

.17שערי תשובה ג:קלט

.25העמק שאלה צד:ה .21מנחת חינוך מצוה רמ

.22מש' בבא קמא פו:

.23בית הבחירה ב"ק צא.

.24כסף הקדשים חו"מ תכ:לט

מ"ש בס' תכ שגם שהמבייש בדברים פטור מ"מ יש

עונש ע"ש נראה שאין זה כי כשעל פי הבחנת השומעי'

יש בדברים ההם סגנון אונאות דברים ונתכוון האומרם

כדי לבייש .משא"כ כשהאומרם הי' סבור שאין

בדברים ההם בחינת בושה לפי השומעים .או שהי'

סבור שכפי הנכון ראוי לו לומר דברים ההם שיש לו

מה שראוי לו לעשות קובלנא על חברו ולהרעים עליו.

גם שנודע שטעה בזה ואין לו שום צד תרעומת עליו

מ"מ כל השומעים מבחינים שהוא הלך בתומו או שהי'

אז מוטעה נראה שפטור מכלום.

También podría gustarte

- Parashas Beha'aloscha: 16 Sivan 5777Documento4 páginasParashas Beha'aloscha: 16 Sivan 5777outdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Chavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתDocumento28 páginasChavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתoutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- 879547Documento2 páginas879547outdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Meaning of The Menorah: Complete Tanach)Documento4 páginasThe Meaning of The Menorah: Complete Tanach)outdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Shavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83lDocumento2 páginasShavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83loutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Shavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83lDocumento2 páginasShavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83loutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Performance of Mitzvos by Conversion Candidates: Rabbi Michoel ZylbermanDocumento6 páginasPerformance of Mitzvos by Conversion Candidates: Rabbi Michoel Zylbermanoutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- 879645Documento4 páginas879645outdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- 879510Documento14 páginas879510outdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Matan Torah Narrative and Its Leadership Lessons: Dr. Penny JoelDocumento2 páginasThe Matan Torah Narrative and Its Leadership Lessons: Dr. Penny Joeloutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Lessons Learned From Conversion: Rabbi Zvi RommDocumento5 páginasLessons Learned From Conversion: Rabbi Zvi Rommoutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Reflections On A Presidential Chavrusa: Lessons From The Fourth Perek of BrachosDocumento3 páginasReflections On A Presidential Chavrusa: Lessons From The Fourth Perek of Brachosoutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Surrogate Challenge: Rabbi Eli BelizonDocumento3 páginasThe Surrogate Challenge: Rabbi Eli Belizonoutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Flowers and Trees in Shul On Shavuot: Rabbi Ezra SchwartzDocumento2 páginasFlowers and Trees in Shul On Shavuot: Rabbi Ezra Schwartzoutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Consent and Coercion at Sinai: Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. SchacterDocumento3 páginasConsent and Coercion at Sinai: Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacteroutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- What Happens in Heaven... Stays in Heaven: Rabbi Dr. Avery JoelDocumento3 páginasWhat Happens in Heaven... Stays in Heaven: Rabbi Dr. Avery Joeloutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Experiencing The Silence of Sinai: Rabbi Menachem PennerDocumento3 páginasExperiencing The Silence of Sinai: Rabbi Menachem Penneroutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- I Just Want To Drink My Tea: Mrs. Leah NagarpowersDocumento2 páginasI Just Want To Drink My Tea: Mrs. Leah Nagarpowersoutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Lessons From Mount Sinai:: The Interplay Between Halacha and Humanity in The Gerus ProcessDocumento3 páginasLessons From Mount Sinai:: The Interplay Between Halacha and Humanity in The Gerus Processoutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Kabbalat Hatorah:A Tribute To President Richard & Dr. Esther JoelDocumento2 páginasKabbalat Hatorah:A Tribute To President Richard & Dr. Esther Joeloutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Torah To-Go: President Richard M. JoelDocumento52 páginasTorah To-Go: President Richard M. Joeloutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Power of Obligation: Joshua BlauDocumento3 páginasThe Power of Obligation: Joshua Blauoutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Yom Hamyeuchas: Rabbi Dr. Hillel DavisDocumento1 páginaYom Hamyeuchas: Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davisoutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Chag Hasemikhah Remarks, 5777: President Richard M. JoelDocumento2 páginasChag Hasemikhah Remarks, 5777: President Richard M. Joeloutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- 879399Documento8 páginas879399outdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Nasso: To Receive Via Email VisitDocumento1 páginaNasso: To Receive Via Email Visitoutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- A Blessed Life: Rabbi Yehoshua FassDocumento3 páginasA Blessed Life: Rabbi Yehoshua Fassoutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Why Israel Matters: Ramban and The Uniqueness of The Land of IsraelDocumento5 páginasWhy Israel Matters: Ramban and The Uniqueness of The Land of Israeloutdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- José Faur: Modern Judaism, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Feb., 1992), Pp. 23-37Documento16 páginasJosé Faur: Modern Judaism, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Feb., 1992), Pp. 23-37outdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- 879400Documento2 páginas879400outdash2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (119)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2099)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- Are We Worthy To Be Saved?Documento3 páginasAre We Worthy To Be Saved?JRHreaderAún no hay calificaciones

- Anchor Bible Series - WikipediaDocumento6 páginasAnchor Bible Series - Wikipediajorge solieseAún no hay calificaciones

- A Kind Word in Response To Those Who Reject Sufism by Shaykh Ahmad Alawi (Qaddas Allahu Sirrihu)Documento191 páginasA Kind Word in Response To Those Who Reject Sufism by Shaykh Ahmad Alawi (Qaddas Allahu Sirrihu)Ahmad AbdlHaqq Ibn AmbroiseAún no hay calificaciones

- MFL 2018 Week 45Documento3 páginasMFL 2018 Week 45hopenow100% (1)

- Enuma Elish - The Babylonian Epic of Creation - 1Documento7 páginasEnuma Elish - The Babylonian Epic of Creation - 1Mi Re LaAún no hay calificaciones

- Star of David Alignment Pattern Indicates Cosmic CountdownDocumento12 páginasStar of David Alignment Pattern Indicates Cosmic CountdownSrinivasKuchurAún no hay calificaciones

- Quran QuizDocumento4 páginasQuran Quizapi-95162675100% (2)

- The Kerygma - School of Evangelization (Talk 2) - HandoutDocumento5 páginasThe Kerygma - School of Evangelization (Talk 2) - HandoutSebastian LopisAún no hay calificaciones

- Ibn Khaldun Speculative KnowledgeDocumento9 páginasIbn Khaldun Speculative KnowledgeNurhanisah SeninAún no hay calificaciones

- Keene Adoniram Judson Biography FinalDocumento20 páginasKeene Adoniram Judson Biography FinalJonathan KeeneAún no hay calificaciones

- Gospel Of: Workbook On TheDocumento29 páginasGospel Of: Workbook On Theaileen coleteAún no hay calificaciones

- 30 Day Prayer GuideDocumento3 páginas30 Day Prayer Guideadamricker100% (1)

- Sermon by Rodney Tan Melaka Gospel Chapel Sunday 21/7/2019Documento29 páginasSermon by Rodney Tan Melaka Gospel Chapel Sunday 21/7/2019Rodney TanAún no hay calificaciones

- Solemnity of The Most Sacred Heart of Jesus - Cycle C PDFDocumento2 páginasSolemnity of The Most Sacred Heart of Jesus - Cycle C PDFKartik MawaAún no hay calificaciones

- Preservation and Authenticity of The QuranDocumento11 páginasPreservation and Authenticity of The QuranProf M. SHAMIMAún no hay calificaciones

- St. Andrew's: United Methodist ChurchDocumento2 páginasSt. Andrew's: United Methodist ChurchColleen RodebaughAún no hay calificaciones

- 10 Steps To Mureedi AmuraqabahDocumento33 páginas10 Steps To Mureedi Amuraqabahawakeni100% (1)

- Story RetellingDocumento4 páginasStory Retellingfilipus krisnaAún no hay calificaciones

- Don Moen Lyrics: God Will Make A Way: A Worship MusicalDocumento3 páginasDon Moen Lyrics: God Will Make A Way: A Worship MusicalJohn ParkAún no hay calificaciones

- Divine Discourses Vol-6Documento225 páginasDivine Discourses Vol-6dattaswamiAún no hay calificaciones

- 2017 - 22 Dec - Forefeast - Festal Matins HymnsDocumento8 páginas2017 - 22 Dec - Forefeast - Festal Matins HymnsMarguerite PaizisAún no hay calificaciones

- Eternal Hearts PDFDocumento2 páginasEternal Hearts PDFTammyAún no hay calificaciones

- Kanzul Eman Sharif (English Translation)Documento516 páginasKanzul Eman Sharif (English Translation)Dar Haqq (Ahl'al-Sunnah Wa'l-Jama'ah)Aún no hay calificaciones

- My Catholic FaithDocumento308 páginasMy Catholic Faithjohn aldred100% (37)

- Nida e HaqqDocumento177 páginasNida e HaqqNoori al-Qadiri100% (4)

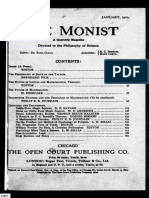

- The Monist: The Open Court Publishing CoDocumento167 páginasThe Monist: The Open Court Publishing Copaskug2Aún no hay calificaciones

- Kerala Temple HistoryDocumento15 páginasKerala Temple Historyjk.dasguptaAún no hay calificaciones

- Kidassehawariyat DeutschDocumento303 páginasKidassehawariyat DeutschWAAAH WaluigiAún no hay calificaciones

- Brunner, Peter, Worship in The Name of Jesus, Part III, The Form of WorshipDocumento50 páginasBrunner, Peter, Worship in The Name of Jesus, Part III, The Form of WorshipSaulo BledoffAún no hay calificaciones

- Mantra For Trouble Free Journey - Prophet666Documento6 páginasMantra For Trouble Free Journey - Prophet666PrasadBhattadAún no hay calificaciones