Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Qualitative Data Analysis: I. Qualitative Data (Thorne, S. RN, PHD, N.D.)

Cargado por

MicahBaclaganTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Qualitative Data Analysis: I. Qualitative Data (Thorne, S. RN, PHD, N.D.)

Cargado por

MicahBaclaganCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

SH1662

Qualitative Data Analysis

I. Qualitative Data (Thorne, S. RN, PhD, n.d.)

Data that approximates or characterizes but does not measure the attributes, characteristics,

properties, etc., of a thing or phenomenon.

Qualitative data come in various forms. In many qualitative studies, the database consists of

interview transcripts from open- ended, focused, but exploratory interviews. However, there is no

limit to what might possibly constitute a qualitative database, and increasingly we are seeing more

and more creative use of such sources as recorded observations (both video and participatory), focus

groups, texts and documents, multimedia or public domain sources, policy manuals, photographs,

and lay autobiographical accounts.

Qualitative data are not the exclusive domain of qualitative research. Rather, the term can refer to

anything that is not quantitative, or rendered into numerical form. Many quantitative studies include

open-ended survey questions, semi-structured interviews, or other forms of qualitative data. What

distinguishes the data in a quantitative study from those generated in a qualitatively designed study is

a set of assumptions, principles, and even values about truth and reality. Quantitative researchers

accept that the goal of science is to discover the truths that exist in the world and to use the scientific

method as a way to build a more complete understanding of reality. Although some qualitative

researchers operate from a similar philosophical position, most recognize that the relevant reality as

far as human experience is concerned, is that which takes place in subjective experience, in social

context, and in historical time. Thus, qualitative researchers are often more concerned about

uncovering knowledge about how people think and feel about the circumstances in which they find

themselves than they are in making judgments about whether those thoughts and feelings are valid.

A. Characteristics of Qualitative Data

• Circular and not linear • Different levels of analysis

• Iterative and not progressive • Different ways of sorting data

• Close interaction with the data

II. Definition of Terms

• Theory: a set of interrelated concepts, definitions and propositions that presents a systematic

view of events or situations by specifying relations among variables.

• Themes: idea categories that emerge from grouping of lower-label data points.

• Characteristic: a single item or event in a text, similar to an individual response to a variable

or indicator in a quantitative research. It is the smallest unit of analysis.

• Coding: the process of attaching labels to lines of text so that the researcher can group and

compare similar o related pieces of information.

• Coding sorts: compilation of similarly coded blocks of text from different sources into a

single file or report.

• Indexing: process that generated a word list comprising of all the substantive words and their

location within the text.

III. Steps in Qualitative Data Analysis (The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education, 2015)

Step 1: Process and Record Data Immediately

As soon as data is collected, it is critical that you immediately process the information and record

detailed notes. These notes could include:

• Things that stuck out to you

14 Handout 1 *Property of STI

Page 1 of 3

SH1662

• Time/date detail

• Other observations

• Highlights from the interaction

• It is important to do this while the interaction is still fresh in your mind so that you can record

your thoughts and reactions as accurately as possible.

• It is helpful to make a reflection sheet template that you carry with you and complete after

each interaction so that it is standardized across all data collection points.

Step 2: Begin Analyzing as Data is Being Collected

Qualitative data analysis should begin as soon as you begin collecting the first piece of

information. The moment the first pieces of data are collected, you should begin reviewing the data

and mentally processing it for themes or patterns that were exhibited. It is important to do this early

so that you will be focused on these patterns and themes as they appear in subsequent data you

collect.

Step 3: Data Reduction

Qualitative studies generally produce a wealth of data but not all of it is meaningful. After data has

been collected, you will need to undergo a data reduction process in order to identify and focus in on

what is meaningful. This is the process of reducing and transforming your raw data.

It is your job as the evaluator to comb through the raw data to determine what is significant and

transform the data into a simplified format that can be understood in the context of the research

questions It was cited in The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education, 2015

that according to, Krathwohl, 1998; Miles and Huberman, 1994; NSF, 1997, when trying to discern

what is meaningful data you should always refer back to your research questions and use them as

your framework. Additionally, you should rely on your own intuition as the evaluator and the

expertise of other individuals with a thorough understanding of the program.

This step does not happen in isolation, it naturally occurs during the first two (2) steps. You are

already reducing data by not recording every single thing that occurs in your data collection

interaction but only recording what you felt was most meaningful, usable, and relevant. You are also

reducing data by looking for themes from the beginning. This process helps you hone in on specific

patterns and themes of interest while not focusing on other aspects of the data.

The process of data reduction, however, must go beyond the data collection stage. Evaluators must

take time to review carefully all of the data you have collected as a whole.

Step 4: Identifying Meaningful Patterns and Themes

In order for qualitative data to be analyzable, it must first be grouped into the meaningful patterns

and/or themes that you observed. This process is the core of qualitative data analysis.

This process is generally conducted in two (2) primary ways:

• Content analysis

• Thematic analysis

The type of analysis is highly dependent on the nature of the research questions and the type(s) of

data you collected. Sometimes a study will use one (1) type of analysis and other times, a study may

use both types.

Content analysis is carried out by:

1. Coding the data for certain words or content

2. Identifying their patterns

3. Interpreting their meanings

14 Handout 1 *Property of STI

Page 2 of 3

SH1662

This type of coding is done by going through all of the text and labelling words, phrases, and

sections of text (either using words or symbols) that relate to your research questions of interest.

After the data is coded, you can sort and examine the data by code to look for patterns.

Thematic analysis – grouping the data into themes that will help answer the research question(s). It

was cited in The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education, 2015 that according

to Taylor-Powell and Renner, 2003 that these themes may be:

• Directly evolved from the research questions and were pre-set before data collection even began; or

• Naturally emerged from the data as the study was conducted

Once your themes have been identified, it is useful to group the data into thematic groups so that you

can analyze the meaning of the themes and connect them back to the research question(s).

Step 5: Data Display

After identifying themes or content patterns, assemble, organize, and compress the data into a display

that facilitates conclusion drawing. The display can be a graphic, table/matrix, or textual display.

• It was cited in The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education, 2015 that

according to Miles and Huberman, 1994; NSF, 1997, regardless of what format you chose, it

should be able to help you arrange and think about the data in new ways and assist you in

identifying systematic patterns and interrelationships across themes and/or content

• Through this process, you should be able to identify patterns and relationships observed within

groups and across groups. For example, using our Summer Program study, you could examine

patterns and themes both within a program city and across program cities.

Step 6: Conclusion Drawing and Verification

Conclusion drawing and verification are the final step in qualitative data analysis. It was cited in The

Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education, 2015 that according to Krathwohl,

1998; Miles and Huberman, 1994; NSF, 1997, to draw reasonable conclusions, you will need to:

• Step back and interpret what all of your findings mean

• Determine how your findings help answer the research question(s)

• Draw implications from your findings

To verify these conclusions, you must revisit the data (multiple times) to confirm the conclusions that

you have drawn.

REFERENCES:

Gibbs. (2012). What is qualitative data analysis? Online QDA. Retrieved on January 21, 2015, from

http://onlineqda.hud.ac.uk/Intro_QDA/what_is_qda.php

The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education. (2015). Retrieved on February

02, 2015, from http://toolkit.pellinstitute.org/evaluation-guide/analyze/analyze-qualitative-

data/#step-2-begin-analyzing-as-data-is-being-collected

Thorne, S. RN, PhD. (n.d.). Qualitative data. Evidence-Base Nursing. Retrieved on January 21,

2015, from http://ebn.bmj.com/content/3/3/68.full

14 Handout 1 *Property of STI

Page 3 of 3

También podría gustarte

- 3is Q4 M1 LESSON 1.1Documento48 páginas3is Q4 M1 LESSON 1.1fionaannebelledanAún no hay calificaciones

- Q4 Module 1.1Documento22 páginasQ4 Module 1.1PsyrosiesAún no hay calificaciones

- BM 33 RP Note 8Documento8 páginasBM 33 RP Note 8anFasAún no hay calificaciones

- Inquiries, Investigation, and Immersion: Quarter 2 Module 1-Lesson 1Documento14 páginasInquiries, Investigation, and Immersion: Quarter 2 Module 1-Lesson 1hellohelloworld100% (1)

- 3is Q2 Module 1.1 1Documento35 páginas3is Q2 Module 1.1 1yrrichtrishaAún no hay calificaciones

- Q4 Triple I Week1Documento16 páginasQ4 Triple I Week1adoygrAún no hay calificaciones

- Interviews II - Data AnalysisDocumento5 páginasInterviews II - Data AnalysisFizzah NaveedAún no hay calificaciones

- Analyzing Data Qualitative Research - RevisedDocumento57 páginasAnalyzing Data Qualitative Research - RevisedJoyz TejanoAún no hay calificaciones

- Data Analysis in Qualitative ResearchDocumento4 páginasData Analysis in Qualitative ResearchRizki AhmadAún no hay calificaciones

- Thematic Analysis inDocumento7 páginasThematic Analysis inCharmis TubilAún no hay calificaciones

- Assignment No. 3Documento13 páginasAssignment No. 3M.TalhaAún no hay calificaciones

- Government College University Faisalabad: Assignment No. 3Documento16 páginasGovernment College University Faisalabad: Assignment No. 3marriam faridAún no hay calificaciones

- Methodology, Scope, Limitatio, Significance, Data Collection and ChapterizationDocumento37 páginasMethodology, Scope, Limitatio, Significance, Data Collection and ChapterizationWZ HakimAún no hay calificaciones

- RP BM 33 Note 8Documento10 páginasRP BM 33 Note 8anFasAún no hay calificaciones

- Collection, Analyses and Interpretation of DataDocumento50 páginasCollection, Analyses and Interpretation of DataJun PontiverosAún no hay calificaciones

- How to Research Qualitatively: Tips for Scientific WorkingDe EverandHow to Research Qualitatively: Tips for Scientific WorkingAún no hay calificaciones

- Data Collection and Analysis, Interpretation and DiscussionDocumento76 páginasData Collection and Analysis, Interpretation and DiscussionWubliker B100% (1)

- III-Topic 5 Finding The Answers To The Research Questions (Data Analysis Method)Documento34 páginasIII-Topic 5 Finding The Answers To The Research Questions (Data Analysis Method)Jemimah Corporal100% (1)

- Inquiries, Investigation, and Immersion: - Third Quarter - Module 1: Finding The Answers To The Research QuestionsDocumento18 páginasInquiries, Investigation, and Immersion: - Third Quarter - Module 1: Finding The Answers To The Research Questionsarmie valdezAún no hay calificaciones

- Date Gathering.Documento45 páginasDate Gathering.Jhona BuendiaAún no hay calificaciones

- Qualitative Data Analysis Methods and TechniquesDocumento7 páginasQualitative Data Analysis Methods and Techniquessisay gebremariamAún no hay calificaciones

- CHAPTER 13 First ReporterDocumento3 páginasCHAPTER 13 First Reportersarah jane villarAún no hay calificaciones

- Patterns & Themes From Data GatheredDocumento44 páginasPatterns & Themes From Data GatheredLeah San DiegoAún no hay calificaciones

- Intro To Qualitative Data Analysis - Si07.wongfDocumento17 páginasIntro To Qualitative Data Analysis - Si07.wongfJohn MalaysiaAún no hay calificaciones

- Iii Las 10 1Documento11 páginasIii Las 10 1reybery26Aún no hay calificaciones

- Kelompok 11 Mardhatillah Salabiayah Analyzing Action Research Data 6.2 What Is Data Analysis?Documento3 páginasKelompok 11 Mardhatillah Salabiayah Analyzing Action Research Data 6.2 What Is Data Analysis?dinaAún no hay calificaciones

- How To Analyze & Interpret DataDocumento27 páginasHow To Analyze & Interpret DataRomer Gesmundo100% (4)

- Content Analysis ReportDocumento4 páginasContent Analysis Reportjanice daefAún no hay calificaciones

- Prepare and Organize Your Data. This May Mean Transcribing Interviews orDocumento4 páginasPrepare and Organize Your Data. This May Mean Transcribing Interviews orRayafitrisariAún no hay calificaciones

- LAS-1 III Q4 Data-Analysis-MethodDocumento16 páginasLAS-1 III Q4 Data-Analysis-MethodJoanna Marey FuerzasAún no hay calificaciones

- Q4 - Inquiries Investigation and Immersion - 12 - WK1 2Documento4 páginasQ4 - Inquiries Investigation and Immersion - 12 - WK1 2shashaAún no hay calificaciones

- Research 1Documento7 páginasResearch 1Sharief Abul EllaAún no hay calificaciones

- IER31 - Notes August 2017Documento8 páginasIER31 - Notes August 2017Lavinia NdelyAún no hay calificaciones

- Las q2 3is Melcweek2Documento7 páginasLas q2 3is Melcweek2Jaylyn Marie SapopoAún no hay calificaciones

- Soma.35.Data Analysis - FinalDocumento7 páginasSoma.35.Data Analysis - FinalAmna iqbal100% (1)

- Practical Research (Assignment)Documento6 páginasPractical Research (Assignment)Azy PeraltaAún no hay calificaciones

- 8) How To Create A Research Design: Lecture Eight: The Main Elements of A Research ProposalDocumento5 páginas8) How To Create A Research Design: Lecture Eight: The Main Elements of A Research ProposalNESRINE ZIDAún no hay calificaciones

- Qualitative Data Analysis InterpretationDocumento29 páginasQualitative Data Analysis InterpretationFazielah GulamAún no hay calificaciones

- Systematic Approaches To Data AnalysisDocumento16 páginasSystematic Approaches To Data AnalysisHumayun ShahNawazAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 9 Final Marketing ResearchDocumento21 páginasChapter 9 Final Marketing ResearchXimena CubillosAún no hay calificaciones

- Data Analysis Method: (Qualitative)Documento25 páginasData Analysis Method: (Qualitative)lili filmAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Methods in Psychology-II: Semesters: BS 6 /M.SC 2 Credit Hours: 3 (2-1) Prepared By: Dr. Riffat SadiqDocumento23 páginasResearch Methods in Psychology-II: Semesters: BS 6 /M.SC 2 Credit Hours: 3 (2-1) Prepared By: Dr. Riffat SadiqAmna ShehzadiAún no hay calificaciones

- PR1Q4W4CADocumento6 páginasPR1Q4W4CAraffy arranguezAún no hay calificaciones

- Grounded Theory DesignsDocumento18 páginasGrounded Theory DesignsIbnu Shollah NugrahaAún no hay calificaciones

- Week11 PDFDocumento5 páginasWeek11 PDFJude BautistaAún no hay calificaciones

- Confidential Data 22Documento12 páginasConfidential Data 22rcAún no hay calificaciones

- (3-Macmillan) Analysing Qualitative DataDocumento23 páginas(3-Macmillan) Analysing Qualitative DataNgọc NgânAún no hay calificaciones

- Caoi Baq Lesson3Documento11 páginasCaoi Baq Lesson3Bee NeilAún no hay calificaciones

- Analyzing Qualitative DataDocumento8 páginasAnalyzing Qualitative DataLilianaAún no hay calificaciones

- How To... Analyse Qualitative DataDocumento11 páginasHow To... Analyse Qualitative DataSoonu AravindanAún no hay calificaciones

- Module 1.1 4TH Quarter InquiriesDocumento20 páginasModule 1.1 4TH Quarter Inquiriesmillarescarl7Aún no hay calificaciones

- Qual Analysis CH 2Documento13 páginasQual Analysis CH 2Joaquim SilvaAún no hay calificaciones

- Senior High School Department: Practical Research 1Documento7 páginasSenior High School Department: Practical Research 1mikhaela sencilAún no hay calificaciones

- Content Analysis: A Qualitative Analytical Research Process by Dr. Radia GuerzaDocumento5 páginasContent Analysis: A Qualitative Analytical Research Process by Dr. Radia GuerzaAliirshad10Aún no hay calificaciones

- Qualitative Data AnalysisDocumento4 páginasQualitative Data AnalysisShambhav Lama100% (1)

- Research Methods - 3Documento48 páginasResearch Methods - 3Kate Zonberga100% (1)

- Inquiries, Investigation, and Immersion: Finding The Answers To The Research Questions (Data Analysis Method)Documento15 páginasInquiries, Investigation, and Immersion: Finding The Answers To The Research Questions (Data Analysis Method)Princess Georgie Rose RodelasAún no hay calificaciones

- TECH RES2 - Lesson 2Documento8 páginasTECH RES2 - Lesson 2SER JOEL BREGONDO Jr.Aún no hay calificaciones

- Research Methods: Simple, Short, And Straightforward Way Of Learning Methods Of ResearchDe EverandResearch Methods: Simple, Short, And Straightforward Way Of Learning Methods Of ResearchCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (13)

- SSIP Application Form 2018-19Documento4 páginasSSIP Application Form 2018-19MD AbdullahAún no hay calificaciones

- Act 550-Education Act 1996Documento80 páginasAct 550-Education Act 1996Angus Tan Shing ChianAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 T Abilitare TuteleaDocumento55 páginas1 T Abilitare TuteleaKean PagnaAún no hay calificaciones

- Department of Education: Weekly Learning Home Plan For Grade 12 WEEK 1, QUARTER 1, OCTOBER 2-6, 2020Documento2 páginasDepartment of Education: Weekly Learning Home Plan For Grade 12 WEEK 1, QUARTER 1, OCTOBER 2-6, 2020Azza ZzinAún no hay calificaciones

- Concept of Dermatoglyphics Multiple Intelligence TestDocumento8 páginasConcept of Dermatoglyphics Multiple Intelligence TestKalpesh TiwariAún no hay calificaciones

- Rivier University TranscriptDocumento3 páginasRivier University Transcriptapi-309139011Aún no hay calificaciones

- LESSON PLAN Template-Flipped ClassroomDocumento2 páginasLESSON PLAN Template-Flipped ClassroomCherie NedrudaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Impact of Childhood Cancer On Family FunctioningDocumento13 páginasThe Impact of Childhood Cancer On Family Functioningapi-585969205Aún no hay calificaciones

- Profiling Infant Olivia & FranzDocumento2 páginasProfiling Infant Olivia & FranzShane Frances SaborridoAún no hay calificaciones

- The Answer Sheet: Teacher's Resignation Letter: My Profession No Longer Exists'Documento11 páginasThe Answer Sheet: Teacher's Resignation Letter: My Profession No Longer Exists'phooolAún no hay calificaciones

- Activity 4 Written Assessment - BambaDocumento3 páginasActivity 4 Written Assessment - BambaMatsuoka LykaAún no hay calificaciones

- Going To The RestaurantDocumento3 páginasGoing To The RestaurantMelvis Joiro AriasAún no hay calificaciones

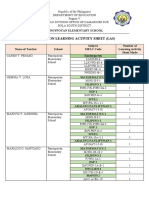

- PANOYPOYAN ES Report On LASDocumento4 páginasPANOYPOYAN ES Report On LASEric D. ValleAún no hay calificaciones

- Catapult RubricDocumento1 páginaCatapult Rubricapi-292490590Aún no hay calificaciones

- Nutrition and Mental Health 2Documento112 páginasNutrition and Mental Health 2M Mutta100% (1)

- Illinois Priority Learning Standards 2020 21Documento187 páginasIllinois Priority Learning Standards 2020 21Sandra PenaAún no hay calificaciones

- Science and Art in Landscape Architecture Knowled-Wageningen University and Research 306322Documento6 páginasScience and Art in Landscape Architecture Knowled-Wageningen University and Research 306322Sangeetha MAún no hay calificaciones

- Cytogenetic TechnologistDocumento2 páginasCytogenetic Technologistapi-77399168Aún no hay calificaciones

- Sex Differences in The Perception of InfidelityDocumento13 páginasSex Differences in The Perception of Infidelityrebela29100% (2)

- Form 2 MathematicsDocumento9 páginasForm 2 MathematicstarbeecatAún no hay calificaciones

- Railway Recruitment Board: Employment Notice No. 3/2007Documento4 páginasRailway Recruitment Board: Employment Notice No. 3/2007hemanth014Aún no hay calificaciones

- Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English DepartmentDocumento10 páginasSarjana Pendidikan Degree in English DepartmentYanti TuyeAún no hay calificaciones

- 90-Minute Literacy Block: By: Erica MckenzieDocumento8 páginas90-Minute Literacy Block: By: Erica Mckenzieapi-337141545Aún no hay calificaciones

- Math LessonDocumento5 páginasMath Lessonapi-531960429Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Essential Difference: The Truth About The Male and Female Brain. New York: Basic BooksDocumento5 páginasThe Essential Difference: The Truth About The Male and Female Brain. New York: Basic BooksIgnetheas ApoiAún no hay calificaciones

- Monitoring and Supervision Tool (M&S) For TeachersDocumento3 páginasMonitoring and Supervision Tool (M&S) For TeachersJhanice Deniega EnconadoAún no hay calificaciones

- 1st - Hobbs and McGee - Standards PaperDocumento44 páginas1st - Hobbs and McGee - Standards Paperapi-3741902Aún no hay calificaciones

- Fifty Years of Supporting Parapsychology - The Parapsychology Foundation (1951-2001)Documento27 páginasFifty Years of Supporting Parapsychology - The Parapsychology Foundation (1951-2001)Pixel PerfectAún no hay calificaciones

- Ngoran Nelson Lemnsa: Personal InformationDocumento2 páginasNgoran Nelson Lemnsa: Personal InformationSanti NgoranAún no hay calificaciones

- Perturbation Theory 2Documento81 páginasPerturbation Theory 2Karine SacchettoAún no hay calificaciones