Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Capitalism and Christianity, American Style: The University of Chicago Press

Cargado por

Jose LeonDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Capitalism and Christianity, American Style: The University of Chicago Press

Cargado por

Jose LeonCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

William Connolly, Capitalism and Christianity, American Style

Capitalism and Christianity, American Style by William Connolly,

Review by: David A. Krueger

The Journal of Religion, Vol. 89, No. 3 (July 2009), pp. 444-446

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/600279 .

Accessed: 21/06/2014 22:02

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Religion.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 22:02:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Journal of Religion

justice as a historically conditioned set of institutional practices. The essays in

the second section place the idea in the context of thought about justice. The

principal figures who come into the discussion here are Kant, Weber, and

Charles Taylor. The essays in the third section deal with the ideal of justice in

the realm of practical, or regional, ethics; Ricoeur’s primary interests here are

legal and medical ethics and their similarities, differences, and relations. In

each of these proceeding sections, issues raised in the first section are taken

up and dealt with at a progressively less abstract level. There is then a discern-

ible trajectory that holds these essays together, one that might be character-

ized, without too much oversimplification, as a movement from abstract struc-

turing of the idea to an analysis of practices by way of configuration. Those

who have any previous experience of Ricoeur’s work will recognize this trajec-

tory.

This is not Ricoeur at his most accessible, and I would not recommend the

work as an entrance point for engaging his corpus. The essays are tough going,

and the essays in the second section are particularly difficult. The essays do

deal with important themes in Ricoeur’s work, ones especially visible in his

later writings. Many of the essays are introduced with footnotes that indicate

a debt to previous works, and nearly all the essays make some reference to the

“little ethics” of Oneself as Another but suggest that knowledge of these works

is not necessary. This is not completely true in my estimation; it is difficult to

discern where Ricoeur is headed in this volume if one knows little or nothing

of where he has been. Some understanding may be gained without previous

knowledge, but grounding in previous works is essential for a thorough un-

derstanding of this volume.

In providing clarification of previous works, Reflections on the Just is excep-

tionally helpful. Of particular interest in this volume is the paradoxical na-

ture of authority—What is authority? How is it legitimated? Is it claimed or

granted?—the existence of vulnerability and passivity within autonomy and ini-

tiative, and the relationship between moral ideals and historical manifestation,

questions that exist more on the margins of Oneself as Another. Those interested

in Ricoeur’s religious thought will find little of direct interest here. Those who

see a deep connection between his moral philosophy and his philosophy of

religion will find some confirmation, but there are other places where the

connections are more explicitly manifest. Reflections on the Just is best ap-

proached as a companion volume to earlier philosophical works, certainly The

Just but perhaps more importantly Oneself as Another. As such, it holds an im-

portant place in Ricoeur’s oeuvre.

W. DAVID HALL, Centre College.

CONNOLLY, WILLIAM. Capitalism and Christianity, American Style. Durham, NC:

Duke University Press, 2008. xvi⫹174 pp. $74.95 (cloth); $21.95 (paper).

The title’s simplicity provides the reader with no clue to the book’s peril. The

complexity and denseness of its argument and language (unnecessarily so to

the mind of this reader) mask the clarity of its promise. James Gustafson, my

former teacher, often asserted his opinion that most good scholarship, at least

in nonscientific fields, ought to be clear to the layperson who stands outside

the academic discipline in which it is written. Such is not the case here. Rather,

this book embodies a highly literate academic’s attempt to reflect on the im-

444

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 22:02:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Book Reviews

pact of conservative Christianity on important recent trends in American po-

litical and economic life in a way that minimizes its possibility for much wide-

spread influence. The arguments are often couched in such specialized

academic jargon that most of those under negative critique (most notably com-

ponents of the Christian religious right) and most of those whom William

Connolly wishes to mobilize for an alternative future (virtually all others but

also some in the religious right) would be utterly “lost in translation.” Such is

the irony of a book surely without such intentions. An author who seeks social

transformation in opposition to harmful elitist hierarchies and in favor of val-

ues such as equality, ecological health and well-being, social democracy, open-

ness, and tolerance writes with highly specialized academic language accessible

to very few outside what might be construed as an elite intellectual subculture.

Furthermore, the reader is forced to work through extensive intellectual side-

bars on early church history and contemporary philosophy that, while inter-

esting to some, do not seem critical to the centrality of the topic implied in

the title of such a short book.

To oversimplify great complexity, the author provides a number of propo-

sitions. Translated into simple English, I would hazard they might be as follows:

(1) The policies of George W. Bush were harmful to our nation and to the

world. (2) Those policies are not arbitrary but are the result of a complex

confluence of factors, including particular religious beliefs and values. (3) To

be more effective, members of the formal academic community ought to be

less “dogmatic” and intolerant of competing methodologies for understanding

the world and ought to be more tolerant and pluralistic in the embrace of

other academic methods. They must avoid the same dangers of fanaticism and

intolerance in some religious believers. (4) Religious belief, Christian or oth-

erwise, is not inherently harmful but must be construed in a way that can be

constructively connected to a new social movement that can counteract the

powerful social trends embodied in the rise to power and the actions and

policies of the Bush administration in its management of the economy and

international affairs.

Connolly’s general argument, still simplified, is something like the following:

Each economic and political system has an ethos, an underlying set of values

and beliefs that give it coherence. By the early twenty-first century, American

capitalism (which the author dubs “cowboy capitalism”), electoral politics, and

the institutional powers of the state became decisively shaped, in part, by the

Christian evangelical right, whose own theological affirmations are embodied

in an ethos of entitlement and revenge. This ethos is represented in religious

popular culture by the fictional Left Behind series by Tim LaHaye. This ethos,

“the evangelical-capitalist resonance machine,” is a loose configuration of ideas

that creates coherence for a system in which those in power feel a sense of

entitlement for the privileges that capitalist institutions and rules bring, as well

as a sense of revenge on those perceived as hostile to this apparently divinely

sanctioned moral order. Thus, Connolly’s central argument about this “reso-

nance machine” turns on his characterization of its ethos or fundamental dis-

position toward the world “that encourages them to transfigure interest into

greed, greed into anti-market ideology, anti-market ideology into market ma-

nipulation, market manipulation into state institutionalization of those oper-

ations, and the entire complex into policies to pull the security net away from

ordinary workers, consumers, and retirees—some of whom are then set up to

translate new intensities of resentment and cynicism into participation in the

445

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 22:02:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Journal of Religion

machine” (43). Revenge is purported to be part and parcel of this religiously

inspired ethos and includes political ruthlessness against any opposing individ-

ual, political party, point of view, or nation-state deemed an enemy. Such real-

life actions are argued to be consistent with “a vengeful vision of the Second

Coming, modeled upon one reading of Revelation and dramatized in the best-

selling series of novels Left Behind . . . [which] maintains the ethos of revenge

expressed . . . on behalf of American sovereignty and world hegemony” (45).

Thus, “cowboy and evangelical spiritualities are not the same. Rather they res-

onate together. The bellicosity and corresponding sense of extreme entitle-

ment of those consumed by economic greed reverberates with the transcen-

dental resentment of those visualizing the righteous violence of Christ” (48).

Connolly’s solution is a “counter-resonance machine” that coheres with a

new, multifaceted, multisectoral, “bottom-up” social movement consistent with

traditional aims of the Democratic Left. This “eco-egalitarian” (capitalist)

movement will embrace core values such as ecological well-being, care for fu-

ture generations, “the diversity of being,” cultural pluralism, lower levels of

material consumption (focusing on “inclusive” goods), and less income and

wealth inequality. While not a theist himself, the author welcomes a pluralism

of “spiritualities” that include appeal to “limited theists” such as William James

and to philosophers such as Nietzsche and Spinoza. Belief in God is permis-

sible, with notions of divine providence open to a God who “learns as the world

turns” and which embraces not only an active human agency that can hopefully

shape the future but also an attitude of humility and intellectual respect for

other world views.

Since this book was completed (summer 2006) and since this review was

written (December 2008), one might note two decisive U.S. events that beg to

serve as critical points of reflection on this book. First, one notes the emergent

U.S. financial crisis, whose tentacles move deeper and broader inside and out-

side our national borders. Surely Connolly would interpret this “event” as con-

firming evidence of his critique and strong sense of moral vices incipient upon

the “evangelical capitalist resonance machine” and also of his strong sense of

the tragic in history. Second is the rapid emergence and election of Barack

Obama. It is my sense that the author was likely caught off guard by this seem-

ing “counter-resonance machine,” with its capacity to engender a social move-

ment that embodies many of the values and goals that Connolly lifts up in his

“interim” agenda. Might it be that the “evangelical capitalist resonance ma-

chine” was not as strong and pervasive as imagined and that the capacity for

renewal and social redirection, both in terms of ethos and social agenda, is

more accessible than imagined? Obama’s movement might have benefited

from this provocative text if it had been offered in translation in publicly ac-

cessible language.

DAVID A. KRUEGER, Baldwin-Wallace College.

ASSMANN, JAN. Of God and Gods: Egypt, Israel, and the Rise of Monotheism. George

L. Mosse Series in Modern European Cultural and Intellectual History. Mad-

ison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2008. x⫹196 pp. $26.96 (paper).

In Of God and Gods, Egyptologist Jan Assmann tackles the subjects of polythe-

ism, monotheism, and the problem of religious violence. This is familiar ter-

ritory for the prolific pen of Assmann, and this volume is a rehearsal and

446

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 22:02:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

También podría gustarte

- Is Critique Secular?: Blasphemy, Injury, and Free SpeechDe EverandIs Critique Secular?: Blasphemy, Injury, and Free SpeechAún no hay calificaciones

- Slavery, Religion and Regime: The Political Theory of Paul Ricoeur as a Conceptual Framework for a Critical Theological Interpretation of the Modern StateDe EverandSlavery, Religion and Regime: The Political Theory of Paul Ricoeur as a Conceptual Framework for a Critical Theological Interpretation of the Modern StateAún no hay calificaciones

- Fundamentalism or Tradition: Christianity after SecularismDe EverandFundamentalism or Tradition: Christianity after SecularismAún no hay calificaciones

- The Politics of Heresy: The Modernist Crisis in Roman CatholicismDe EverandThe Politics of Heresy: The Modernist Crisis in Roman CatholicismAún no hay calificaciones

- A Comparative Sociology of World Religions: Virtuosi, Priests, and Popular ReligionDe EverandA Comparative Sociology of World Religions: Virtuosi, Priests, and Popular ReligionAún no hay calificaciones

- Classical and Protestant Liberalism: Differences and SimilaritiesDe EverandClassical and Protestant Liberalism: Differences and SimilaritiesCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- Freedom from Reality: The Diabolical Character of Modern LibertyDe EverandFreedom from Reality: The Diabolical Character of Modern LibertyAún no hay calificaciones

- Behind the Myths: The Foundations of Judaism, Christianity and IslamDe EverandBehind the Myths: The Foundations of Judaism, Christianity and IslamAún no hay calificaciones

- The Economy of Desire (The Church and Postmodern Culture): Christianity and Capitalism in a Postmodern WorldDe EverandThe Economy of Desire (The Church and Postmodern Culture): Christianity and Capitalism in a Postmodern WorldCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (2)

- Freedom and Virtue: The Conservative Libertarian DebateDe EverandFreedom and Virtue: The Conservative Libertarian DebateAún no hay calificaciones

- Anarchy and the Kingdom of God: From Eschatology to Orthodox Political Theology and BackDe EverandAnarchy and the Kingdom of God: From Eschatology to Orthodox Political Theology and BackAún no hay calificaciones

- Earthly Things: Immanence, New Materialisms, and Planetary ThinkingDe EverandEarthly Things: Immanence, New Materialisms, and Planetary ThinkingAún no hay calificaciones

- The Clash of Orthodoxies: Law, Religion, and Morality in CrisisDe EverandThe Clash of Orthodoxies: Law, Religion, and Morality in CrisisAún no hay calificaciones

- Dialogues between Faith and Reason: The Death and Return of God in Modern German ThoughtDe EverandDialogues between Faith and Reason: The Death and Return of God in Modern German ThoughtAún no hay calificaciones

- Sociology Through the Eyes of FaithDe EverandSociology Through the Eyes of FaithCalificación: 2.5 de 5 estrellas2.5/5 (1)

- Pagans and Christians in the City: Culture Wars from the Tiber to the PotomacDe EverandPagans and Christians in the City: Culture Wars from the Tiber to the PotomacAún no hay calificaciones

- Perspectives: Redemption, Economics, Law, Justice, Mediation, Human Rights: Redemption, Economics, Law, Justice, Mediation, Human RightsDe EverandPerspectives: Redemption, Economics, Law, Justice, Mediation, Human Rights: Redemption, Economics, Law, Justice, Mediation, Human RightsAún no hay calificaciones

- Knowledge Unto Relationship: A Biblical DestinyDe EverandKnowledge Unto Relationship: A Biblical DestinyAún no hay calificaciones

- The Body of Faith: A Biological History of Religion in AmericaDe EverandThe Body of Faith: A Biological History of Religion in AmericaAún no hay calificaciones

- Fighting Words: Religion, Violence, and the Interpretation of Sacred TextsDe EverandFighting Words: Religion, Violence, and the Interpretation of Sacred TextsAún no hay calificaciones

- Kneeling at the Altar of Science: The Mistaken Path of Contemporary Religious ScientismDe EverandKneeling at the Altar of Science: The Mistaken Path of Contemporary Religious ScientismAún no hay calificaciones

- Never Sorry: Confronting Perennial Theological Challenges With ApologeticsDe EverandNever Sorry: Confronting Perennial Theological Challenges With ApologeticsAún no hay calificaciones

- Citizens of the Broken Compass: Ethical and Religious Disorientation in the Age of TechnologyDe EverandCitizens of the Broken Compass: Ethical and Religious Disorientation in the Age of TechnologyAún no hay calificaciones

- What Matters?: Ethnographies of Value in a (Not So) Secular AgeDe EverandWhat Matters?: Ethnographies of Value in a (Not So) Secular AgeAún no hay calificaciones

- The Art of Contextual Theology: Doing Theology in the Era of World ChristianityDe EverandThe Art of Contextual Theology: Doing Theology in the Era of World ChristianityCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- Fragile Finitude: A Jewish Hermeneutical TheologyDe EverandFragile Finitude: A Jewish Hermeneutical TheologyAún no hay calificaciones

- Earnestly Contending: Religious Freedom and Pluralism in Antebellum AmericaDe EverandEarnestly Contending: Religious Freedom and Pluralism in Antebellum AmericaAún no hay calificaciones

- State of Affairs: The Science-Theology ControversyDe EverandState of Affairs: The Science-Theology ControversyAún no hay calificaciones

- Otherness and Ethics: An Ethical Discourse of Levinas and Confucius (Kongzi)De EverandOtherness and Ethics: An Ethical Discourse of Levinas and Confucius (Kongzi)Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ethics without Principles: Another Possible Ethics—Perspectives from Latin AmericaDe EverandEthics without Principles: Another Possible Ethics—Perspectives from Latin AmericaAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Theology, Constitutionalism, and the StateDe EverandIslamic Theology, Constitutionalism, and the StateCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (2)

- Contemporary Religiosities: Emergent Socialities and the Post-Nation-StateDe EverandContemporary Religiosities: Emergent Socialities and the Post-Nation-StateAún no hay calificaciones

- Ethical Empowerment: Virtue Beyond the ParadigmsDe EverandEthical Empowerment: Virtue Beyond the ParadigmsAún no hay calificaciones

- Value and Vulnerability: An Interfaith Dialogue on Human DignityDe EverandValue and Vulnerability: An Interfaith Dialogue on Human DignityMatthew R. PetrusekAún no hay calificaciones

- Islam and Christianity: Theological Themes in Comparative PerspectiveDe EverandIslam and Christianity: Theological Themes in Comparative PerspectiveCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2)

- Working Alternatives: American and Catholic Experiments in Work and EconomyDe EverandWorking Alternatives: American and Catholic Experiments in Work and EconomyAún no hay calificaciones

- The Ocean of God: On the Transreligious Future of ReligionsDe EverandThe Ocean of God: On the Transreligious Future of ReligionsAún no hay calificaciones

- Tive For Survival, Regulative of Life Prospects, or Simply Life-Enhancing. Claims For MoreDocumento4 páginasTive For Survival, Regulative of Life Prospects, or Simply Life-Enhancing. Claims For MoreAnas MahmoodAún no hay calificaciones

- Sociology ProjectDocumento28 páginasSociology ProjectMili JainAún no hay calificaciones

- Differences e VersionDocumento40 páginasDifferences e VersionstilichoAún no hay calificaciones

- Concept of ReligionDocumento6 páginasConcept of ReligionDaniel TincuAún no hay calificaciones

- Rationalization and Developmental HistoryDocumento13 páginasRationalization and Developmental HistoryIoannis KyriakantonakisAún no hay calificaciones

- Beck2014 PDFDocumento14 páginasBeck2014 PDFJose LeonAún no hay calificaciones

- Olmsted - Real Enemies - Conspiracy Theories and American Democracy, World War I To 9 - 11-Oxford University Press (2009) PDFDocumento335 páginasOlmsted - Real Enemies - Conspiracy Theories and American Democracy, World War I To 9 - 11-Oxford University Press (2009) PDFJose Leon100% (2)

- Undone Science: Charting Social Movement and Civil Society Challenges To Research Agenda SettingDocumento31 páginasUndone Science: Charting Social Movement and Civil Society Challenges To Research Agenda SettingJose LeonAún no hay calificaciones

- Julian LopezDocumento476 páginasJulian LopezJose LeonAún no hay calificaciones

- Three KindsDocumento18 páginasThree KindsJose LeonAún no hay calificaciones

- Robert K. Merton - On The Shoulders of Giants - A Shandean Postscript-Free Press (1965) PDFDocumento303 páginasRobert K. Merton - On The Shoulders of Giants - A Shandean Postscript-Free Press (1965) PDFJose Leon100% (2)

- Interrupting The Human Rights Expansion Narrative: José Julián LópezDocumento15 páginasInterrupting The Human Rights Expansion Narrative: José Julián LópezJose LeonAún no hay calificaciones

- Evangelicalism and Capitalism in Translantic ContextDocumento24 páginasEvangelicalism and Capitalism in Translantic ContextJose LeonAún no hay calificaciones

- Interview: Reflections On The Last Utopia': A Conversation With Samuel MoynDocumento10 páginasInterview: Reflections On The Last Utopia': A Conversation With Samuel MoynJose LeonAún no hay calificaciones

- Including Outsiders in Latin AmericaDocumento27 páginasIncluding Outsiders in Latin AmericaJose LeonAún no hay calificaciones

- Changing Repertoires and Partisan Ambivalence in The New Brazilian ProtestsDocumento16 páginasChanging Repertoires and Partisan Ambivalence in The New Brazilian ProtestsJose LeonAún no hay calificaciones

- Harding 1991 Representing FundamentalismDocumento21 páginasHarding 1991 Representing FundamentalismJose LeonAún no hay calificaciones

- Ox Horn 1996Documento19 páginasOx Horn 1996Jose LeonAún no hay calificaciones

- Alex Klaasse Resume 24 June 2015Documento1 páginaAlex Klaasse Resume 24 June 2015api-317449980Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Whole History of Kinship Terminology in Three Chapters: Before Morgan, Morgan, and After MorganDocumento20 páginasThe Whole History of Kinship Terminology in Three Chapters: Before Morgan, Morgan, and After MorganlunorisAún no hay calificaciones

- Thus at Least Presuppose, and Should Perhaps Make Explicit, A Normative AccountDocumento5 páginasThus at Least Presuppose, and Should Perhaps Make Explicit, A Normative AccountPio Guieb AguilarAún no hay calificaciones

- The Myth of Asia's MiracleDocumento15 páginasThe Myth of Asia's MiracleshamikbhoseAún no hay calificaciones

- Pe 3 (Module 1) PDFDocumento6 páginasPe 3 (Module 1) PDFJoshua Picart100% (1)

- ACTIVITY 1 PhiloDocumento2 páginasACTIVITY 1 PhiloColeen gaboyAún no hay calificaciones

- VB2 DA 2020.01.07 NguyenthisongthuongDocumento5 páginasVB2 DA 2020.01.07 NguyenthisongthuongVũ Thanh GiangAún no hay calificaciones

- Violence Against Women in IndiaDocumento5 páginasViolence Against Women in IndiaInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Aún no hay calificaciones

- Questionnaire Family Constellation.Documento3 páginasQuestionnaire Family Constellation.Monir El ShazlyAún no hay calificaciones

- The Mysic "Omega" of End-Time CrisisDocumento82 páginasThe Mysic "Omega" of End-Time Crisisanewgiani6288Aún no hay calificaciones

- Good Answers Guide 2019Documento101 páginasGood Answers Guide 2019kermitspewAún no hay calificaciones

- Drawing The Mind Into The Heart, by David BradshawDocumento16 páginasDrawing The Mind Into The Heart, by David BradshawKeith BuhlerAún no hay calificaciones

- Rakshit Shankar CVDocumento1 páginaRakshit Shankar CVﱞﱞﱞﱞﱞﱞﱞﱞﱞﱞﱞﱞAún no hay calificaciones

- Design PrinciplesDocumento6 páginasDesign PrinciplesAnastasia MaimescuAún no hay calificaciones

- Internaltional ManagementDocumento28 páginasInternaltional ManagementramyathecuteAún no hay calificaciones

- Contemporary Arts 12 CalligraphyDocumento21 páginasContemporary Arts 12 Calligraphyjiecell zyrah villanuevaAún no hay calificaciones

- W4 LP Precalculus 11Documento6 páginasW4 LP Precalculus 11Jerom B CanayongAún no hay calificaciones

- IB SCA Assessment OverviewDocumento11 páginasIB SCA Assessment OverviewShayla LeeAún no hay calificaciones

- Bibliography: BooksDocumento3 páginasBibliography: BooksAaditya BhattAún no hay calificaciones

- David Georgi - Language Made Visible - The Invention of French in England After The Norman Conquest (PHD Thesis) - New York University (2008)Documento407 páginasDavid Georgi - Language Made Visible - The Invention of French in England After The Norman Conquest (PHD Thesis) - New York University (2008)Soledad MussoliniAún no hay calificaciones

- Nasir Khusraw HunsbergerDocumento10 páginasNasir Khusraw Hunsbergerstudnt07Aún no hay calificaciones

- Chaudhry 2011 Wife BeatingDocumento24 páginasChaudhry 2011 Wife BeatingdcAún no hay calificaciones

- Auto AntonymsDocumento4 páginasAuto AntonymsMarina ✫ Bačić KrižanecAún no hay calificaciones

- Session Plan On The Youth Program (Boy Scout of The Philippines)Documento3 páginasSession Plan On The Youth Program (Boy Scout of The Philippines)Blair Dahilog Castillon100% (2)

- Political Science ProjectDocumento20 páginasPolitical Science ProjectAishwarya RavikhumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Arts Summative Test: Choices: Pre-Historic Egyptian Greek Roman Medieval RenaissanceDocumento1 páginaArts Summative Test: Choices: Pre-Historic Egyptian Greek Roman Medieval RenaissanceMark Anthony EsparzaAún no hay calificaciones

- Contemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions Philippine Literature: Forms, Elements and PrinciplesDocumento10 páginasContemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions Philippine Literature: Forms, Elements and Principlesshiella mae baltazar100% (4)

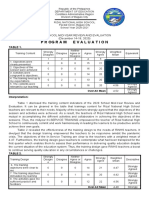

- Program Evaluation: Table 1Documento3 páginasProgram Evaluation: Table 1Joel HinayAún no hay calificaciones

- Drawing Portraits Faces and FiguresDocumento66 páginasDrawing Portraits Faces and FiguresAaron Kandia100% (2)

- Kokoro No FurusatoDocumento27 páginasKokoro No FurusatoJoaoPSilveiraAún no hay calificaciones