Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

The Hadees On Intentions and Actions

Cargado por

New Age IslamTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

The Hadees On Intentions and Actions

Cargado por

New Age IslamCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

The Hadees on Intentions and Actions

THE Hadees about intentions is so important, some scholars have expressed the opinion that it encompasses fully

one third of Islamic teachings. Also, it is one of the most remembered and quoted Ahadees and one that is

frequently quoted in its original Arabic even by non-Arabic speaking Muslims. There is hardly a Muslim who has

never heard it. While all this attention to its words is superb, unfortunately we have not done as much to

understand its implications and let that understanding informs our actions. From Islamic perspective our actions

can fall in one of three categories and our intentions have different implications for each of them.

In the first category are the religiously mandatory acts or the voluntary acts of worship (like voluntary Salat). In

the second category are the permissible acts that include most of the mundane activities in life, like eating,

drinking, sleeping, earning a living, and raising a family. The third category consists of prohibited acts.

The most direct application of this Hadees is to the first category. It tells us that such deeds must be performed

for the sole purpose of pleasing Allah for even the slightest corruption of our motives could destroy them. The five

pillars are the prime example of such deeds. For example if a person offers Salat (prayers) to be recognised as a

pious person, he has not only destroyed his Salat, he has committed the unforgivable sin of associating partners

with Allah, for he was praying for the sake of others.

The same is true of Hajj, Zakat, fasting and charity etc. The Qur’an explains it further through a beautiful simile.

Those who spend their wealth seeking God’s approval and to strengthen their souls may be compared to a garden

on a hilltop; should a rainstorm strike it, its produce is doubled, while if a rainstorm does not strike it, then drizzle

does. God is Observant of anything you do.” [Al-Baqarah 2:264-265 (Translation by Irving)].

Charity is an important example because here the chances of corruption of our motives are especially high due to

the very nature of the act. We deal with other people who may thank and recognise us and we may begin to love

and seek that appreciation. What is more, we may brush aside any qualms by assuring ourselves that the publicity

is only meant to inspire others.

If we keep this background in mind, we can begin to see the now nearly routine practice of holding a fundraising

dinner — by the Muslims living in the West — very differently. It is obvious that this is not a Muslim institution; they

borrowed it from their host countries. And they did so without much thought. For here are its underlying ideas.

First, a nice dinner in a nice restaurant is a way of putting people in the mood.

Second, advertising each donation is a means of inspiring others as well as rewarding the donors.

Third, high-pressure techniques, like putting people on the spot, are quite productive.

Each of these elements is poles apart from Islamic teachings. A Muslim gives out of concern for his hereafter, not

by being lulled into giving by posh surroundings. He knows that the reward for his donation depends upon the

sincerity with which it is given and not its monetary amount. He is fully aware that this sincerity and purity of

intention are his most important assets, for without them his most generous donation may bring nothing but

disaster. A person with such concerns would be very leery of going to a fundraising dinner with his donations. An

entire community of such people would be very reluctant to hold such an event in its present form.

For our failures or shortcomings, we have the satisfaction that our intentions were good. In the worst case we may

interpret the Hadees to suggest that the ends justify the means. We need to remember that sheer good intentions

do not repair a bad act. If we do not perform our Salat or sacrifice or hajj correctly, mere good intentions will not

make them right. The extreme case is that of justifying a known prohibited act based on good intentions. “It is like

playing games with the religion,” says Maulana Manzoor Naumani. He goes on to add that such an act could

tremendously add to one’s burden of sin.

With regard to the second category (permissible mundane acts) our intentions have a potential for turning them

into acts of worship. This is also an aspect we ignore to our own loss. For here is the possibility of turning every

moment of our life into an act of worship through a change in our intentions. For example, when a believer goes to

his place of work with the intention of fulfilling his religious responsibility to provide for his family and earn Halal

living, he may be engaged in the same physical activity as the next person but his outlook is very different. And so

is his reward! Through this small effort we could really be living for a higher purpose, and at a higher level.

Get updated Islamic News

También podría gustarte

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2104)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- ProductionDocumento37 páginasProductionRosarito Saravia EscobarAún no hay calificaciones

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- A Manifesto of Student Liberation From Leftist Tyranny2Documento24 páginasA Manifesto of Student Liberation From Leftist Tyranny2sechAún no hay calificaciones

- ScoutingDocumento23 páginasScoutingJoemari MislangAún no hay calificaciones

- InHealth ListProviderDocumento481 páginasInHealth ListProviderganang19Aún no hay calificaciones

- Breadwinner TDocumento5 páginasBreadwinner Tapi-238206331Aún no hay calificaciones

- Analiysis BorobudurDocumento10 páginasAnaliysis BorobudurArtika WulandariAún no hay calificaciones

- Islamic Heritage of Peace, Tolerance CelebratedDocumento1 páginaIslamic Heritage of Peace, Tolerance CelebratedNew Age IslamAún no hay calificaciones

- Al-Azhar Stands For Moderation of ThoughtDocumento2 páginasAl-Azhar Stands For Moderation of ThoughtNew Age IslamAún no hay calificaciones

- Redefining Islam For The 21st CenturyDocumento1 páginaRedefining Islam For The 21st CenturyNew Age IslamAún no hay calificaciones

- Does Erdogan Intend To Open The Doors of IjtihadDocumento1 páginaDoes Erdogan Intend To Open The Doors of IjtihadNew Age IslamAún no hay calificaciones

- Is This The Islam of Prophet Mohammad, A Blessing To Mankind?Documento4 páginasIs This The Islam of Prophet Mohammad, A Blessing To Mankind?New Age IslamAún no hay calificaciones

- New Age Islam HistoryDocumento1 páginaNew Age Islam HistoryNew Age IslamAún no hay calificaciones

- Internship Report On: Meezan Bank LimitedDocumento11 páginasInternship Report On: Meezan Bank LimitedHusnain AttiqueAún no hay calificaciones

- 22 MoriscosDocumento18 páginas22 Moriscosapi-3860945Aún no hay calificaciones

- I Had Reached To Your DoorstepsDocumento2 páginasI Had Reached To Your DoorstepsDash Hunter75% (8)

- History 1 Readings in Philippine Histor Y: Mhie B. Daniel InstructorDocumento7 páginasHistory 1 Readings in Philippine Histor Y: Mhie B. Daniel InstructorInahkoni Alpheus Sky OiragasAún no hay calificaciones

- Students List of Tribal HostelDocumento68 páginasStudents List of Tribal HostelSami Ullah Sami UllahAún no hay calificaciones

- Overpayment Re HP (540) Apr 2020Documento296 páginasOverpayment Re HP (540) Apr 2020Jaffy Brian DaligdigAún no hay calificaciones

- Nastikpedia Volume 3 Moha Banganik Grontho Quran Assembled by Chinku MofizDocumento1900 páginasNastikpedia Volume 3 Moha Banganik Grontho Quran Assembled by Chinku MofizYakoob ChowdhuryAún no hay calificaciones

- Aplikasi Kaedah Fiqh "Al-Darurah Tuqaddaru Bi Qadariha" Terhadap Pengambilan Bantuan Makanan Oleh GelandanganDocumento12 páginasAplikasi Kaedah Fiqh "Al-Darurah Tuqaddaru Bi Qadariha" Terhadap Pengambilan Bantuan Makanan Oleh Gelandanganputri525Aún no hay calificaciones

- Malaysia PetroDocumento75 páginasMalaysia PetroEldrazi100% (1)

- Euthanasia: (Mercy Killing)Documento16 páginasEuthanasia: (Mercy Killing)Rukmana Tri YunityaningrumAún no hay calificaciones

- Draft - RRLDocumento7 páginasDraft - RRLMhot Rojas UnasAún no hay calificaciones

- Rekap Absen PKKMB 2020Documento25 páginasRekap Absen PKKMB 2020bagus pribadiAún no hay calificaciones

- KhutbahDocumento14 páginasKhutbahferyltriadiAún no hay calificaciones

- Punctuation Fix J SofiaDocumento6 páginasPunctuation Fix J SofiaSofiauswaAún no hay calificaciones

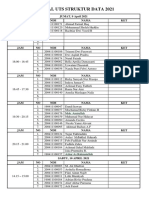

- JADWAL UTS STRUKTUR DATA 2021 - C Dan ADocumento3 páginasJADWAL UTS STRUKTUR DATA 2021 - C Dan APrasetyo Adi Pratama NugrohoAún no hay calificaciones

- Eid e GhadeerDocumento3 páginasEid e GhadeerYusuf JafferyAún no hay calificaciones

- Aligarh MovementDocumento2 páginasAligarh MovementPrashant TiwariAún no hay calificaciones

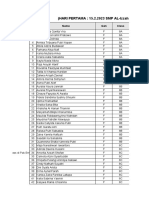

- Senarai Nama Buddy TerkiniDocumento14 páginasSenarai Nama Buddy TerkiniYap Yu SiangAún no hay calificaciones

- ReflectionDocumento2 páginasReflectionapi-220189108Aún no hay calificaciones

- List of Candidates Admitted Into The Naub Remedial Programme PDFDocumento12 páginasList of Candidates Admitted Into The Naub Remedial Programme PDFAtanda Babatunde MutiuAún no hay calificaciones

- Quran NotesDocumento16 páginasQuran NotesMohammad SalehAún no hay calificaciones

- Batch12 BASIC IT TEST NITBDocumento102 páginasBatch12 BASIC IT TEST NITBJahangeer MagrayAún no hay calificaciones

- Angels Dhikr ShortDocumento17 páginasAngels Dhikr ShortS.SadiqAún no hay calificaciones

- Islam in TamilnaduDocumento116 páginasIslam in TamilnadurosgazAún no hay calificaciones