Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Achilles Tendon

Cargado por

ojuditaDescripción original:

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Achilles Tendon

Cargado por

ojuditaCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Achilles Tendon rupture

Achilles tendon rupture is not a pleasant experience. Research suggests that the Achilles is

one of the most frequently ruptured tendons, mainly occurring in middleaged men during

sporting activities (that’s not an excuse to sit on the sofa with a brew and a chocolate biscuit).

And the incidence of ruptures is on the increase.

There are two main schools of thought when it comes to rehabilitation: surgical repair or

nonsurgical rehab. In addition, it has become common after surgery to include early

functional mobilisation, such as using an adjustable brace, and now the same approach is

being taken with promising results in non-surgical settings.

But how do we know which approach is the most effective? Patient-reported outcome scores

are an increasingly popular way to help therapists evaluate functional results and to compare

incapacity on an individual level. Several valid and reliable scores are in general use for

shoulder, knee and ankle injuries, and there are also specific scoring systems for evaluating

patients with patellar tendinosis and Achilles tendinopathy. But what if your tendon has gone

snap and you are recovering from a rupture? Researchers based in Sweden have the

solution(‘The Achilles tendon total rupture score (ATRS):development and validation’, The

American Journal of Sports Medicine2007: 35 (3) 421-426), an easily self-administered,

validated and sensitive scoring system with high reliability, which evaluates symptoms and

their effect on physical activity in patients with Achilles tendon rupture. For the first time,

clinicians have a tool that will allow them to compare and contrast different rehabilitation

modalities.

The new patient-reported outcome measure (ATRS) can be completed in a couple of minutes,

and the score from the 10 items is determined in less than a minute, providing a useful tool

for rehabilitation staff to see just how well their rehab programme is going.

Taking the strain

Tendons are specialised structures that transfer forces between muscles and bones. The

frequency, duration, and/or magnitude of tendon forces can change dramatically in response

to changes in physical activity and muscle strength, but little is known about the interactions

between muscle and tendon adaptations in living people. Researchers from California have

just completed a study to see if the Achilles tendon adapts to changes in muscle strength to

maintain strains within a preferred operating range (‘Achilles tendon adaptation during

strength training in young adults’, Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise.

Subjects taking part in the study performed an eight-week strength-training programme (3 x

10 heel raises at 70% of maximum force) consisting of three weekly sessions separated by at

least one day of rest. They were tested before and at the end of the first, second, fourth, sixth

and eighth weeks to see if increased strength had an effect on the peak strain in the Achilles

tendon.

This is the first study to have quantified Achilles tendon strain throughout a strength training

programme; what it showed was that the Achilles seems to have a preferred strain limit that is

maintained even as muscle strength increases. The actual level of strain seems to vary greatly

between individuals.

Does eccentric loading work? It’s not just top athletes who get problems with their Achilles

tendons. A sore Achilles can also stop us mere mortals in our tracks. If you trawl through the

research you will find numerous studies expounding the virtues of different strategies for the

rehabilitation of Achilles tendinopathy, including, controversially, the use of eccentric calf

muscle training.

The use of eccentric loading to rehabilitate tendon injuries first came to light in the mid

1980s, but it wasn’t until the late 1990s that the rehab community fully embraced the

concept. While there is a lot of support for this intervention with an athletic population, there

is very little evidence to suggest that it is an effective treatment within a ‘non-athletic’

population (by which we mean you, probably most of your clients, and me!).

Researchers from Keele University School of Medicine in the UK undertook a study to fill

the knowledge gap (‘Eccentric calf muscle training in non-athletic patients with Achilles

tendinopathy’, Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2007: 10 52-58). To qualify as

sedentary, the patients taking part in the study had to have had a physical activity exercise

habit over a six-month period of less than three 20-min exercise sessions a week.

The patients (who all had Achilles tendinopathy) underwent a graded progressive eccentric

calf strengthening exercise programme (heel drops) for 12 weeks. They were advised to

continue the exercises through mild or moderate pain, stopping only if the pain became

unbearable.

At the start of the study the patients completed the VISA-A questionnaire – 10 questions

developed by the Victorian Institute of Sport in Australia to assess pain and activity. They

continued to complete the questionnaire at subsequent visits.

Forty-four per cent of the patients did not improve with eccentric exercise, and the

researchers concluded that, while the programme was effective in almost 60% of subjects, it

might not benefit sedentary patients to the same extent as has been reported in athletes. That

said, I’ve worked with plenty of athletes with niggly Achilles tendons, and I’ve found that

although eccentric loading worked wonders with some, it didn’t make any difference for

others…

Personally I’m not sure it has much to do with activity levels. The key is not to take a one-

size-fits-all approach. Eccentric loading is going to work for some people, and not for others.

También podría gustarte

- An Esoteric Guide To Laws of FormDocumento52 páginasAn Esoteric Guide To Laws of FormeQualizerAún no hay calificaciones

- Seascape With Sharks and DancerDocumento5 páginasSeascape With Sharks and DancerMartina Goldring0% (3)

- Eccentric or Concentric Exercises For The Treatment of TendinopathiesDocumento11 páginasEccentric or Concentric Exercises For The Treatment of TendinopathiesAnonymous xvlg4m5xLXAún no hay calificaciones

- Exercises for Patella (Kneecap) Pain, Patellar Tendinitis, and Common Operations for Kneecap Problems: - Understanding kneecap problems and patellar tendinitis - Conservative rehabilitation protocols - Rehabilitation protocols for lateral release, patellar realignment, medial patellofemoral ligament reDe EverandExercises for Patella (Kneecap) Pain, Patellar Tendinitis, and Common Operations for Kneecap Problems: - Understanding kneecap problems and patellar tendinitis - Conservative rehabilitation protocols - Rehabilitation protocols for lateral release, patellar realignment, medial patellofemoral ligament reCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- Emotion Code-Body Code Consent AgreementDocumento1 páginaEmotion Code-Body Code Consent Agreementapi-75991446100% (1)

- AchillesDocumento65 páginasAchillesHamka HamAún no hay calificaciones

- Anxiety and Anxiety DisordersDocumento2 páginasAnxiety and Anxiety DisordersJohn Haider Colorado GamolAún no hay calificaciones

- Isometric Exercise To Reduce Pain in Patellar Tendinopathy In-Season Is It Effective "On The Road?"Documento5 páginasIsometric Exercise To Reduce Pain in Patellar Tendinopathy In-Season Is It Effective "On The Road?"Ana ToscanoAún no hay calificaciones

- Kinesio TapingDocumento26 páginasKinesio Tapingapi-495322975Aún no hay calificaciones

- Lectures On Levinas Totality and InfinityDocumento108 páginasLectures On Levinas Totality and InfinityEmanuel DueljzAún no hay calificaciones

- Muhurtha Electional Astrology PDFDocumento111 páginasMuhurtha Electional Astrology PDFYo DraAún no hay calificaciones

- Radial Shockwave TherapyDocumento4 páginasRadial Shockwave TherapyMilos MihajlovicAún no hay calificaciones

- 99999Documento18 páginas99999Joseph BaldomarAún no hay calificaciones

- The Recovery Process of ACL Tears: Scott 1Documento17 páginasThe Recovery Process of ACL Tears: Scott 1api-410307925Aún no hay calificaciones

- Heavy-Load Eccentric Calf Muscle Training For The Treatment of Chronic Achilles TendinosisDocumento8 páginasHeavy-Load Eccentric Calf Muscle Training For The Treatment of Chronic Achilles TendinosisburgoschileAún no hay calificaciones

- Effects of Distally Fixated Versus Nondistally Fixated Leg Extensor Resistance Training On Knee Pain in The Early Period After Anterior Cruciate Ligament ReconstructionDocumento9 páginasEffects of Distally Fixated Versus Nondistally Fixated Leg Extensor Resistance Training On Knee Pain in The Early Period After Anterior Cruciate Ligament ReconstructionMirna Vasquez MacayaAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is Knee Taping?: Ads Local Stem Cells Therapy Kinesiology TapesDocumento4 páginasWhat Is Knee Taping?: Ads Local Stem Cells Therapy Kinesiology TapesHamka HamAún no hay calificaciones

- Helping The Total Knee Replacement (TKR) Client Post Therapy and Beyond by Chris Gellert, PT, Mmusc & Sportsphysio, MPT, CSCS, AmsDocumento5 páginasHelping The Total Knee Replacement (TKR) Client Post Therapy and Beyond by Chris Gellert, PT, Mmusc & Sportsphysio, MPT, CSCS, AmsChrisGellertAún no hay calificaciones

- Aaa - THAMARA - Comparing Hot Pack, Short-Wave Diathermy, Ultrasound, and Tens On Isokinetic Strength, Pain and Functional StatusDocumento9 páginasAaa - THAMARA - Comparing Hot Pack, Short-Wave Diathermy, Ultrasound, and Tens On Isokinetic Strength, Pain and Functional StatusBruno FellipeAún no hay calificaciones

- Alfredson AchillesDocumento7 páginasAlfredson AchillesTonyAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is Knee Taping?: Taping .. Local Stem Cells Therapy Kinesiology TapesDocumento4 páginasWhat Is Knee Taping?: Taping .. Local Stem Cells Therapy Kinesiology TapesHamka HamAún no hay calificaciones

- Effect of Isometric Quadriceps Exercise On Muscle Strength, Pain, and Function in Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Controlled StudyDocumento4 páginasEffect of Isometric Quadriceps Exercise On Muscle Strength, Pain, and Function in Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Controlled StudyHusnannisa ArifAún no hay calificaciones

- Hamstring Muscle Strain Treated by Mobilizing The Sacroiliac JointDocumento4 páginasHamstring Muscle Strain Treated by Mobilizing The Sacroiliac JointKarthik BhashyamAún no hay calificaciones

- Effect of Isometric Quadriceps Exercise On Muscle StrengthDocumento7 páginasEffect of Isometric Quadriceps Exercise On Muscle StrengthAyu RoseAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is Knee Taping?Documento3 páginasWhat Is Knee Taping?Hamka HamAún no hay calificaciones

- Effect of Eccentric VS Isometric On TendinitisDocumento6 páginasEffect of Eccentric VS Isometric On TendinitisOctavian CatanăAún no hay calificaciones

- Knee Brace & Knee Braces With Strengthening Exercise Incomplete Tear ACLDocumento5 páginasKnee Brace & Knee Braces With Strengthening Exercise Incomplete Tear ACLخالد الشهرانيAún no hay calificaciones

- 0269215511423557Documento10 páginas0269215511423557Jose Maria DominguezAún no hay calificaciones

- Effect of Tai Chi Exercise On Proprioception of Ankle and Knee Joints in Old PeopleDocumento5 páginasEffect of Tai Chi Exercise On Proprioception of Ankle and Knee Joints in Old PeoplePhooi Yee LauAún no hay calificaciones

- Tendão, ExercícioDocumento8 páginasTendão, ExercícioFabiano LacerdaAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Paper On Acl InjuriesDocumento6 páginasResearch Paper On Acl Injuriesvasej0nig1z3100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S0929664619300567 MainDocumento8 páginas1 s2.0 S0929664619300567 Mainananta restyAún no hay calificaciones

- 3-6 - Isometric Exercise Versus Combined Concentric Eccentric Exercise Training in Patients With Osteoarthritis KneeDocumento7 páginas3-6 - Isometric Exercise Versus Combined Concentric Eccentric Exercise Training in Patients With Osteoarthritis KneeirmarizkyyAún no hay calificaciones

- Acl N PilatesDocumento8 páginasAcl N PilatesDeva JCAún no hay calificaciones

- Lee 2017Documento8 páginasLee 2017toaldoAún no hay calificaciones

- Aust JPhysiotherv 51 I 1 ShawDocumento9 páginasAust JPhysiotherv 51 I 1 ShawPrime PhysioAún no hay calificaciones

- 01 DelmoreJSR 20120046-EjDocumento10 páginas01 DelmoreJSR 20120046-EjAqila NurAún no hay calificaciones

- Tendon Neuroplastic TrainingDocumento8 páginasTendon Neuroplastic TrainingFrantzesco KangarisAún no hay calificaciones

- PhysicalTreatments v4n1p25 en PDFDocumento9 páginasPhysicalTreatments v4n1p25 en PDFFadma PutriAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Article: Effects of Low-Level Laser Therapy and Eccentric Exercises in The Treatment of Patellar TendinopathyDocumento7 páginasResearch Article: Effects of Low-Level Laser Therapy and Eccentric Exercises in The Treatment of Patellar TendinopathyAlvin JulianAún no hay calificaciones

- Tendon Neuroplastic Training Changing The Way We Think About Tendon RehabilitationDocumento8 páginasTendon Neuroplastic Training Changing The Way We Think About Tendon RehabilitationfilipecorsairAún no hay calificaciones

- Impact of Exercise On The Functional Capacity and Pain of Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical TrialDocumento7 páginasImpact of Exercise On The Functional Capacity and Pain of Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Clinical TrialSunithaAún no hay calificaciones

- Comparison of Supervised Exercise and Home Exercise After Ankle FractureDocumento6 páginasComparison of Supervised Exercise and Home Exercise After Ankle FractureKaren MuñozAún no hay calificaciones

- PE067 Handout Shoulder Special Tests and The Rotator Cuff With DR Chris LittlewoodDocumento5 páginasPE067 Handout Shoulder Special Tests and The Rotator Cuff With DR Chris LittlewoodTomáš KrajíčekAún no hay calificaciones

- Effects of 4 Weeks of Elastic-Resistance Training On Ankle-Evertor Strength and LatencyDocumento17 páginasEffects of 4 Weeks of Elastic-Resistance Training On Ankle-Evertor Strength and LatencyUpender YadavAún no hay calificaciones

- Full TextDocumento9 páginasFull TextdespAún no hay calificaciones

- Musculoskeletal Atrophy in An Experimental Model of Knee OsteoarthritisDocumento8 páginasMusculoskeletal Atrophy in An Experimental Model of Knee OsteoarthritisirmarizkyyAún no hay calificaciones

- Ever Considered Being An Astronaut PhysiotherapistDocumento13 páginasEver Considered Being An Astronaut Physiotherapistvivi225100% (1)

- RecoveryDocumento139 páginasRecoveryIgnacio VázquezAún no hay calificaciones

- 209 FullDocumento23 páginas209 FullMarta MontesinosAún no hay calificaciones

- Physical Therapy in Sport: Seth O'Neill, Simon Barry, Paul WatsonDocumento8 páginasPhysical Therapy in Sport: Seth O'Neill, Simon Barry, Paul WatsonmorbreirAún no hay calificaciones

- Acl Injury Research PaperDocumento6 páginasAcl Injury Research Paperrvpchmrhf100% (1)

- Comparacion Articulos de Tres Ejercicios para Manguito Rotador en InglesDocumento26 páginasComparacion Articulos de Tres Ejercicios para Manguito Rotador en IngleskarolndAún no hay calificaciones

- Continued Sports Activity Using A Pain-MonitoringDocumento12 páginasContinued Sports Activity Using A Pain-Monitoring杨钦杰Aún no hay calificaciones

- International Journal of Health Sciences and ResearchDocumento8 páginasInternational Journal of Health Sciences and Researchrizk86Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ijerph 16 03509Documento11 páginasIjerph 16 03509Chloe BujuoirAún no hay calificaciones

- Literature Review Acl InjuryDocumento8 páginasLiterature Review Acl Injurycdkxbcrif100% (1)

- Hydrotherapy Aids OsteoarthritisDocumento3 páginasHydrotherapy Aids OsteoarthritisRene Lugo MedinaAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 s2.0 S1607551X09703614 MainDocumento8 páginas1 s2.0 S1607551X09703614 MainAchenk BarcelonistaAún no hay calificaciones

- Chest Expander Spring A Low Cost Home Physiotherapybased Exercise Rehabilitation After Total Hip ArthroplastyDocumento11 páginasChest Expander Spring A Low Cost Home Physiotherapybased Exercise Rehabilitation After Total Hip ArthroplastyAmar DahmaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Apa Science Fair 1Documento17 páginasApa Science Fair 1api-420731316Aún no hay calificaciones

- Effect of Wii FitTM Exercise Therapy On Gait Parameters in Ankle Sprain Patients A Randomised Controlled TrialDocumento23 páginasEffect of Wii FitTM Exercise Therapy On Gait Parameters in Ankle Sprain Patients A Randomised Controlled TrialWalaa EldesoukeyAún no hay calificaciones

- 16 - Cross EducationDocumento26 páginas16 - Cross Educationbreinfout fotosAún no hay calificaciones

- For Your Health: Knee Arthritis and Muscle Strength - The Truth Is GrayDocumento1 páginaFor Your Health: Knee Arthritis and Muscle Strength - The Truth Is GrayRakhshasaAún no hay calificaciones

- Levine - Rehabilitation After Total Hip and Knee ArthroplastyDocumento6 páginasLevine - Rehabilitation After Total Hip and Knee Arthroplastyma_zinha_22Aún no hay calificaciones

- Co Teaching Lesson Plan-Parity-Discussion QuestionsDocumento7 páginasCo Teaching Lesson Plan-Parity-Discussion Questionsapi-299624417Aún no hay calificaciones

- (Light Novel) Otorimonogatari (English)Documento269 páginas(Light Novel) Otorimonogatari (English)Yue Hikaru0% (1)

- Plagiarism PDFDocumento28 páginasPlagiarism PDFSamatha Jane HernandezAún no hay calificaciones

- Disney EFE MatrixDocumento3 páginasDisney EFE Matrixchocoman231100% (1)

- Mid Term Report First Term 2014Documento13 páginasMid Term Report First Term 2014samclayAún no hay calificaciones

- Pengaruh Pandemi Covid-19 Terhadap Faktor Yang Menentukan Perilaku Konsumen Untuk Membeli Barang Kebutuhan Pokok Di SamarindaDocumento15 páginasPengaruh Pandemi Covid-19 Terhadap Faktor Yang Menentukan Perilaku Konsumen Untuk Membeli Barang Kebutuhan Pokok Di SamarindaNur Fadillah Rifai ScevitAún no hay calificaciones

- Name of The Subject: Human Resource Management Course Code and Subject Code: CC 204, HRM Course Credit: Full (50 Sessions of 60 Minutes Each)Documento2 páginasName of The Subject: Human Resource Management Course Code and Subject Code: CC 204, HRM Course Credit: Full (50 Sessions of 60 Minutes Each)pranab_nandaAún no hay calificaciones

- Letter of Request: Mabalacat City Hall AnnexDocumento4 páginasLetter of Request: Mabalacat City Hall AnnexAlberto NolascoAún no hay calificaciones

- Industrial Organizational I O Psychology To Organizational Behavior Management OBMDocumento18 páginasIndustrial Organizational I O Psychology To Organizational Behavior Management OBMCarliceGAún no hay calificaciones

- How Research Benefits Nonprofits Shao Chee SimDocumento24 páginasHow Research Benefits Nonprofits Shao Chee SimCamille Candy Perdon WambangcoAún no hay calificaciones

- 1948 Union Citizenship Act, Eng PDFDocumento9 páginas1948 Union Citizenship Act, Eng PDFathzemAún no hay calificaciones

- Colegiul National'Nicolae Balcescu', Braila Manual English Factfile Clasa A Vi-A, Anul V de Studiu, L1 Profesor: Luminita Mocanu, An Scolar 2017-2018Documento2 páginasColegiul National'Nicolae Balcescu', Braila Manual English Factfile Clasa A Vi-A, Anul V de Studiu, L1 Profesor: Luminita Mocanu, An Scolar 2017-2018Luminita MocanuAún no hay calificaciones

- Project Quality ManagementDocumento9 páginasProject Quality ManagementelizabethAún no hay calificaciones

- Can Plan de Lectie 5Documento3 páginasCan Plan de Lectie 5Tatiana NitaAún no hay calificaciones

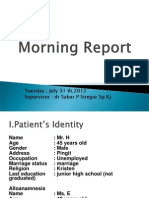

- Tuesday, July 31 TH, 2012 Supervisor: DR Sabar P Siregar SP - KJDocumento44 páginasTuesday, July 31 TH, 2012 Supervisor: DR Sabar P Siregar SP - KJChristophorus RaymondAún no hay calificaciones

- A Practical Guide To Effective Behavior Change How To Apply Theory-And Evidence-Based Behavior ChangeDocumento15 páginasA Practical Guide To Effective Behavior Change How To Apply Theory-And Evidence-Based Behavior ChangeccarmogarciaAún no hay calificaciones

- Grading Rubric For A Research Paper-Any Discipline: Introduction/ ThesisDocumento2 páginasGrading Rubric For A Research Paper-Any Discipline: Introduction/ ThesisJaddie LorzanoAún no hay calificaciones

- Sophie Lee Cps Lesson PlanDocumento16 páginasSophie Lee Cps Lesson Planapi-233210734Aún no hay calificaciones

- Personality Development in Infancy, A Biological ApproachDocumento46 páginasPersonality Development in Infancy, A Biological ApproachAdalene SalesAún no hay calificaciones

- Different HR M Case StudyDocumento5 páginasDifferent HR M Case StudyMuhammad Ahmad Warraich100% (1)

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in EnglishDocumento2 páginasA Detailed Lesson Plan in EnglishMaria Vallerie FulgarAún no hay calificaciones

- Education Inequality Part 2: The Forgotten Heroes, The Poor HeroesDocumento1 páginaEducation Inequality Part 2: The Forgotten Heroes, The Poor HeroesZulham MahasinAún no hay calificaciones

- Aqa Cat RM Criteria 2013-14Documento32 páginasAqa Cat RM Criteria 2013-14aneeshj1Aún no hay calificaciones