Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Nushki PDF

Cargado por

asad ullahTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Nushki PDF

Cargado por

asad ullahCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

bs_bs_banner

Nursing and Health Sciences (2013), 15, 229–234

Research Article

Human Capital Questionnaire: Assessment of European

nurses’ perceptions as indicators of human capital quality

Montserrat Yepes-Baldó, PhD, Marina Romeo, PhD and Rita Berger, PhD

Department of Social Psychology, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

Abstract Healthcare accreditation models generally include indicators related to healthcare employees’ perceptions

(e.g. satisfaction, career development, and health safety). During the accreditation process, organizations are

asked to demonstrate the methods with which assessments are made. However, none of the models provide

standardized systems for the assessment of employees. In this study, we analyzed the psychometric properties

of an instrument for the assessment of nurses’ perceptions as indicators of human capital quality in healthcare

organizations. The Human Capital Questionnaire was applied to a sample of 902 nurses in four European

countries (Spain, Portugal, Poland, and the UK). Exploratory factor analysis identified six factors: satisfaction

with leadership, identification and commitment, satisfaction with participation, staff well-being, career devel-

opment opportunities, and motivation. The results showed the validity and reliability of the questionnaire,

which when applied to healthcare organizations, provide a better understanding of nurses’ perceptions, and is

a parsimonious instrument for assessment and organizational accreditation. From a practical point of view,

improving the quality of human capital, by analyzing nurses and other healthcare employees’ perceptions, is

related to workforce empowerment.

Key words factor analysis, health care, human capital, nurses’ satisfaction, psychometric.

INTRODUCTION Background

The accreditation of healthcare centres today is an integral In Europe, the first accreditation programs, based on the

part of healthcare system quality in over 70 countries North American models of the Joint Commission on Hospital

(Greenfield & Braithwaite, 2009). In order to obtain this Accreditation, grew in the 1990s (Shaw, 2006; Shaw et al.,

accreditation, different models for quality assessment exist. 2010). By 2011, there were different active accreditation

All these models include a section referring to human capital organizations in Europe, including Spain, the UK, Portugal,

in healthcare organizations (Veillard et al., 2005; Generalitat and Poland. Some (e.g. in some regions of Spain, such as

de Catalunya, 2007; Joint Commission International, 2010). Catalonia or Andalusia) follow the European Foundation

In this context, the interest in human capital is related to for the Quality Management (EFQM) model (EFQM, 2007;

providing the best care for patients, due to the relationship 2010) adapted to healthcare organizations, while others (e.g.

between healthcare employees’ perceptions and their work Poland) are based on the World Health Organization (WHO)

behaviors (Mitchell et al., 2001; Ying et al., 2007). Researchers Regional Office for Europe Performance Assessment Tool

have suggested that employees’ perceptions of their jobs are for quality improvement in Hospitals (PATH) (Veillard et al.,

related to quality indicators, such as positive individual- and 2005), the International Society for Quality in Healthcare

organizational-level performance outcomes (e.g. Ying et al., (ISQua) (ISQua, 2007) (UK and Portugal), or the Joint Com-

2007; Crook et al., 2011). mission International (Portugal and Spain) (Joint Commis-

Our aim in this study was to develop a valid, reliable, and sion International, 2010).

parsimonious assessment instrument for measuring nurses’ In general terms, all the referred models include indicators

perceptions as indicators of human capital quality in health- related to employee satisfaction, career development, and

care organizations in order to provide them with standard- health-safety perceptions. Nonetheless, these core indicators

ized instruments during accreditation processes. have been conceptualized from different perspectives and

measured in different ways. In this sense, the EFQM model

includes employees’ satisfaction in the perception measures

Correspondence address: Montserrat Yepes-Baldó, Passeig de la Vall d’Hebron, 171,

(called “perceptions” in the 2010 model). This dimension

Facultad de Psicologia, Barcelona 08035, Spain. Email: myepes@ub.edu

Received 3 May 2012; revision received 5 November 2012; accepted 6 November includes employees’ satisfaction in relation to aspects, such as

2012. motivation, sense of belonging, communication, personal

© 2012 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12024

230 M. Yepes-Baldó et al.

relationships, training, career development, equal opportuni- evaluate the adequacy of each of the statements on a five-

ties, or health and safety. point scale (1 = inadequate to 5 = highly adequate) (Oster-

Although it brings the EFQM fundamental concepts of lind, 1989). Statements with an average score ⱕ 3 were

excellence closer to health care (Vallejo et al., 2006), the eliminated. None of the judges recommended further items

PATH model includes staff satisfaction in the staff orienta- be deleted, but they suggested additional items related to

tion dimension, but is related exclusively to work satisfaction. commitment and identification (Romeo et al., 2011a,b), and

Additionally, the PATH model assesses climate, opportuni- motivation (Navarro et al., 2011), considered as fundamental

ties for continued learning and training, work implication and concepts related to human capital by the European Network

values, and health-promotion activities and safety initiatives. of Work and Organizational Psychologists (ENOP, 2005). The

The ISQua model includes satisfaction, career develop- final questionnaire had 39 items.

ment, and health safety as indicators of human capital quality The original version of the HCQ questionnaire was in

on Function b: Support Services (Standard 4: Human Spanish. The items were translated and back-translated and

Resources Management). It also includes dimensions related adapted to Catalan, English, Polish, and Portuguese. The

to engagement, participation and supervision, and staff well- objective of the translation process was to keep the instru-

being. Finally, the Joint Commission International model ment as close as possible to the original, maintaining the

includes staff satisfaction monitoring and staff health and direction of each question and the same structure presented

safety program measurements. by the authors. Therefore, a back-translation method

These models generally include different aspects regarding (Carlson, 2000) and the guidelines of the International Test

employees’ satisfaction, career development, and health- Commission (ITC, 2010) to obtain a linguistically-equivalent

safety perceptions to evaluate human capital quality. During instrument in all languages were used; first with the collabo-

the accreditation process, organizations are asked to demon- ration of expert consultants, the translation into Catalan,

strate how this assessment has been made and with what English, Polish, and Portuguese was done, and then it was

methods. However, none of the models provide standardized back-translated from Catalan, English, Polish, and Portu-

systems for employee assessment. According to Shaw (2000), guese into Spanish. All discrepancies were amended, and a

it is important for organizations to have standardized instru- common version was derived.

ments to measure employees’ perceptions during accredita-

tion processes, because this is crucial to the consistency of

reports within programs. Participants

The questionnaire thus created was applied to a sample of

902 nurses working in public hospitals in four European

Study aim countries (Portugal, 57.6%; Spain, 32%; Poland, 6.2%; and

Our aim in this study was to develop the Human Capital the UK, 4.1%). Participants in all cases were volunteers. Of

Questionnaire (HCQ), which is a standardized, valid, reli- the total, 10.9% identified themselves as managers. No

able, and parsimonious assessment instrument for measuring response was received from 7.98%, and 65.6% worked on

nurses’ perceptions as indicators of human capital quality in rotating shifts. Sample description by country can be seen in

healthcare organizations. Table 1.

METHODS Ethical considerations

Prior to the data collection, approval to conduct the study

Instrument development was obtained from the research and training committees at

Indicators related to peoples’ perceptions have to be meas- the participant hospitals. Additionally, all participant nurses

urable, meaningful, and quantifiable (Kim et al., 2010). The received a letter explaining the purposes and procedures of

underlying theoretical basis for item generation was an the study, were assured that their confidentiality and ano-

analysis of the most used accreditation models (Veillard nymity would be maintained, and were informed their right

et al., 2005; EFQM, 2007; 2010; ISQua, 2007; Joint Commis- to withdraw from the study at any time without negative

sion International, 2010), and the employees’ perception impact. Confidentiality of responses was ensured.

dimensions most commonly included in them related to

nurses’ satisfaction, career development, and health-safety

Data collection

perceptions.

Twenty-six item statements were generated. The content The HCQ was administered to nurses over a three week

validity of the items was supported by the literature and period, with the help of an internal collaborator. After a

consultation with healthcare professionals. All items were briefing, given by a member of the research team, the ques-

scored on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly tionnaire was distributed around various units and general

disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). buildings of the hospitals, and completed anonymously by

Additionally, 26 statements were evaluated by a panel of volunteers who were able to respond during their work time.

10 judges who were specialists in human resource assess- The volunteers did not receive any compensation for their

ment in healthcare organizations. The judges were asked to participation.

© 2012 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd.

Nurses’ perceptions of human capital 231

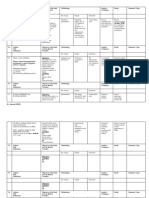

Table 1. Sample description by country

Variables Portugal Spain Poland UK Total

n (%) 520 (57.6%) 289 (32%) 56 (6.2%) 37 (4.1%) 902 (100%)

Managers 56 (10.8%) 16 (5.5%) 4 (7.1%) 22 (59.5%) 98 (10.9%)

Rotating shifts 403 (77.5%) 138 (47.8%) 35 (62.5%) 16 (43.2%) 592 (65.6%)

A&E 89 (17.1%) 35 (12.1%) 0 (0%) 3 (8.1%) 127 (14.1%)

Surgery 55 (10.6%) 37 (12.8%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 92 (10.2%)

Outpatients’ consultations 35 (6.7%) 32 (11.1%) 7 (12.5%) 0 (0%) 74 (8.2%)

Administration 5 (0.9%) 4 (1.4%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 9 (1%)

Ward nurses 309 (59.4%) 142 (49.1%) 48 (85.7%) 23 (62.2%) 522 (57.9%)

Others 5 (0.9%) 18 (6.2%) 0 (0%) 9 (24.3%) 32 (3.6%)

N/A 22 (4.2%) 21 (7.3%) 1 (1.8%) 2 (5.4%) 46 (5.1%)

A&E, Accident & Emergency, N/A, not available.

Data analysis Romeo et al. (2011a) and Romeo et al.’s (2011b) studies,

this factor was titled “identification and commitment”, and

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed to estab-

included 10 items.

lish the internal structure of the instrument. EFA was used in

Factor 3, which explained 7.42% of the variance, was

validity testing when the factor structure is unknown a priori

related to nurses’ satisfaction with participation and

(Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Principal components extrac-

decision-making (e.g. “I believe that the level of participation

tion with Varimax rotation was calculated using all of the

that exists is effective”). Consequently, and based on Yepes’s

variance of the manifest variables, and all of that variance

(2010) study, we named this factor “satisfaction with partici-

appears in the solution (Ford et al., 1986).

pation”. It included five items.

To assess the adequacy of the sample, the Kaiser–Meyer–

Factor 4 explained 3.88% of the variance. It included items

Olkin index (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (BTS)

related to staff well-being, health, and safety (e.g. “In this

were calculated. The factor loadings (> 0.40) and communali-

organization, management is concerned with finding solu-

ties (> 0.30) were used to assess the adequacy of individual

tions to fatigue, work-related illness, and accidents”). This

items (Pett et al., 2003).

factor was titled “staff well-being”, and included five items.

Internal consistency was evaluated as a measure of the

Factor 5 explained 3.76% of the variance and concerned

reliability of the HCQ. This was done by calculating Cron-

the possibility to develop professionally in the organization

bach’s a, which is considered to be the optimal method for

(e.g. “There are interesting opportunities to progress in this

determining internal consistency, as it takes into account the

trust”). This factor was titled “career development opportu-

degree of covariance between the test items. As a criterion,

nities”, and included four items.

the value of Cronbach’s a should be at least 0.6.

The last factor, factor 6, explained 2.78% of the total vari-

ance, and included items related to the degree of effort that

RESULTS people are willing to exert in their work (e.g. “I feel like I

want to make an effort with my work”). Based on Navarro

The KMO (0.947) and BTS (16330.7, P < 0.001) showed et al.’s (2011) study, this factor was titled “motivation”, and

sample adequacy for factorial analysis. Two items, related to included three items.

nurses’ satisfaction (“I don’t like how this organization func- All factors had a scores greater than 0.6. Correlations

tions; I will go to a better one as soon as I can”) and career between factors and a scores can be seen in Table 2.

development (“I feel satisfied with the possibilities for me to

learn and to develop professionally”), were eliminated from

DISCUSSION

the scale due to their ambiguous factor loadings. The first

item had a factor loading greater than 0.4 in two components, The results of the exploratory analysis showed that the ques-

while the second item was a single-item factor. tionnaire was structured into six factors, four of which were

The final 37 items loaded onto six factors and explained related to the dimensions of the main quality models previ-

60.71% of the variance. The first factor explained 34.05% of ously described, and two – commitment and motivation –

the variance. This factor included 10 items, all related to related to experts’ advice.

nurses’ satisfaction with their managers. Consequently, it was Related to the components of the scale, the analysis of the

titled “satisfaction with managers”. An example of items items contained within the first factor revealed that they all

included “I feel satisfied with the support I receive from my referred to aspects of nurses’ satisfaction with their manag-

immediate superiors”. ers. This result was in accordance with the majority of the

Factor 2, which explained 8.87% of the variance, involved previously-mentioned accreditation models, which included a

items related to engagement, commitment, and identification dimension related to leaders’ role and skills in their assess-

(“I feel emotionally linked to this hospital”). Based on ment (collaborative management on the Joint Commission

© 2012 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd.

232 M. Yepes-Baldó et al.

Table 2. Correlations between factors and a scores

Variables Variable 1 Variable 2 Variable 3 Variable 4 Variable 5 Variable 6

1. Satisfaction with managers (0.943)

2. Identification and commitment 0.419* (0.905)

3. Satisfaction with participation 0.464* 0.408* (0.877)

4. Staff well-being 0.522* 0.414* 0.550* (0.740)

5. Career development opportunities 0.452* 0.404* 0.552* 0.594* (0.771)

6. Motivation 0.339* 0.340* 0.204* 0.232* 0.204* (0.624)

Note: a scores in parentheses. *P < 0.001.

International model, supervisor support on the ISQua model, quality literature (e.g. Cooper, 2009; Preheim et al., 2009;

and satisfaction with leaders on the EFQM and PATH Watts, 2010; Werner & Konetzka, 2010).

models). The last factor included items related to motivation,

In the analysis of factor items, and based on Berger et al.’s defined by Quijano et al., 1998, p. 195 as “the degree of effort

(2012) study, we defined this dimension as the degree of that people are willing to exert in their work”.

employees’ satisfaction with their managers.

The second factor included items related to the relation-

ship between nurses and their organizations. It included Limitations and future research

items related to commitment and identification, and based on

There are some limitations in this study. It should be noted

Romeo et al. (2011a) and Romeo et al.’s (2011b) studies, we

that the samples of this study were restricted to large and

named this factor “identification and commitment”. Organi-

medium-size hospitals, and therefore, the questionnaire

zational commitment has been defined as “the psychological

should be tested both with other samples and in other

link that employees develop towards the organization for

contexts. This would entail testing the extent to which the

different reasons. As an attitude it is based on beliefs, evalu-

model is applicable across different healthcare organizations,

ation processes, feelings and behaviors” (Romeo et al., 2011a,

and would provide further assurances as to its conceptual

p. 2). Identification is defined as a type of link with the organi-

robustness.

zation that implies cognition, affection, and desire, and it is

Finally, future research with the questionnaire should use

composed of three dimensions: pride, categorization, and

convergent and discriminating validation and organizational

cohesion (Quijano et al., 2000; Romeo et al., 2011a,b). The

effectiveness criteria in order to avoid the risk of generating

first two factors explained 42.92% of the variance.

spurious correlations through common-method variance

The third factor included items related to participation and

(Podsakoff & Organ, 1986).

decision-making. All of the items referred to aspects of

nurses’ satisfaction with the levels of participation that the

organization allowed, and its adequacy (Yepes, 2010). This

Conclusion

result was in accordance with the ISQua model, which

includes the need for seeking the views of professionals and The questionnaire obtained was a clear, parsimonious, and

other stakeholders in order to ensure staff participation on synthetic tool that was theoretically founded on quality-

the development of standards (ISQua, 2007). assessment models. It was based on empirical data, and was

The fourth factor (related to staff well-being) and the fifth comprehensible to employees and managers. The main

factor (related to career development opportunities) were in advantage of the questionnaire was its usefulness in the

line with of all the accreditation models previously men- evaluation of nurses and other healthcare employees’ per-

tioned. They included these aspects as part of the quality of ceptions as indicators of human capital, and to assess partici-

human capital (competent and capable workforce on the pants’ results with respect to the EFQM model (EFQM,

Joint Commission International model; promote staff well- 2007; 2010), ISQua model (ISQua, 2007), WHO–PATH

being and relevant training, and the development opportuni- model (Veillard et al., 2005), and Joint Commission Interna-

ties on the ISQua model; health promotion activities and tional model (Joint Commission International, 2010).

safety initiatives, and training career development on the Accordingly, it would be useful for healthcare organizations

EFQM model; and positively enabling conditions, and oppor- to evaluate their human capital in order to obtain an official

tunities for continued learning and training on the PATH accreditation.

model). Several studies have shown the importance of staff Additionally, from an intervention point of view, the results

well-being as related to individual and organizational per- showed that the dimensions “satisfaction with managers” and

formance (e.g. Dugan et al., 1996; Aldana, 2001; Lundstrom “identification and commitment” explained the main part of

et al., 2002; United States Agency for Health Care Research the variance of the HCQ. In this sense, any plan that aims to

and Quality, 2003; Burke et al., 2009). Finally, career and com- improve the quality of human capital in the healthcare sector

petencies development opportunities are important topics in should take into account both dimensions.

© 2012 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd.

Nurses’ perceptions of human capital 233

Finally, from a practical point of view, it is important to Greenfield D, Braithwaite J. Developing the evidence base for

note that improving the quality of human capital, by analyz- accreditation of health care organisations: a call for transparency

ing nurses and other healthcare employees’ perceptions, is and innovation. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2009; 18: 162–163.

related to workforce empowerment (ISQua, 2007). Specifi- International Test Commission (ITC). International test commission

guidelines for translating and adapting tests. 2010. [Cited 3 Apr

cally, it allows the best care of patients, due to the relationship

2012.] Available from URL: http://www.intestcom.org/upload/

between nurses’ perceptions and their work behaviour (Ying sitefiles/40.pdf.

et al., 2007) or their intention to stay with their organizations ISQua. International Accreditation Standards for Healthcare External

(Mitchell et al., 2001). Evaluation. Dublin: The International Society for Quality in

Health Care, 2007.

Joint Commission International. International essentials of health

CONTRIBUTIONS care quality and patient safety. 2010. [Cited 3 Apr 2012]. Avalaible

Study Design and Data Collection: MYB, MR, RB. from URL: http://www.jointcommissioninternational.org.

Kim LLK, Chan CCA, Dallimore D. Perceptions of human capital

Data Analysis: MYB, MR.

measures: from corporate executives and investors. J. Bus. Psychol.

Manuscript Writing: MYB, MR, RB. 2010; 25: 673–688. doi: 10.1007/s10869-009-9150-0.

Lundstrom T, Pugliese G, Bartley J, Cos J, Guither C. Organiza-

tional and environmental factors that affect worker health and

ACKNOWLEDGMENT safety and patient outcomes. Am. J. Infect. Control 2002; 30:

The study was partially funded by the European Commis- 93–106.

sion, Leonardo da Vinci Program (Project: ES/04/B/F/ Mitchell TR, Holtom BC, Lee TW, Sablynski CJ, Erez M. Why

PP-149162 – Human System Audit for the Health Care people stay: using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turno-

ver. Acad. Manage. J. 2001; 44: 1102–1121.

Sector-HSA).

Navarro J, Yepes M, Ayala Y, Quijano S. An integrated model of

work motivation applied in a multicultural sample. Rev. Psicol.

REFERENCES Trab. Organ. 2011; 27: 177–190.

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory (3rd edn). New

Aldana S. Financial impact of health promotion programs: a com- York: McGraw-Hill, 1994.

prehensive review of the literature. Am. J. Health Promot. 2001; 15: Osterlind J. Constructing Item Test. New York: Kluwer Academic

296–320. Pub, 1989.

Berger R, Romeo M, Guardia J, Yepes M, Soria MA. Psychometric Pett MA, Lackey NR, Sullivan JJ. Making Sense of Factor Analysis:

properties of the Spanish Human System Audit short-scale of The Use of Factor Analysis for Instrument Development in Health

transformational leadership. Span. J. Psychol. 2012; 15: 367–376. Care Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2003.

doi:dx.doi.org/10.5209/rev_SJOP.2012.v15.n1.37343. Podsakoff PM, Organ DW. Self-reports in organizational research:

Burke RJ, Ng ESW, Fiksenbaum L. Virtues, work satisfactions and problems and prospects. J. Manage. 1986; 12: 531–544.

psychological wellbeing among nurses. Int. J. Workplace Health Preheim GJ, Armstrong GE, Barton AJ. The new fundamentals in

Manage. 2009; 2: 202–219. nursing: introducing beginning quality and safety education for

Carlson ED. A case study in translation methodology using the nurses’ competencies. J. Nurs. Educ. 2009; 48: 694–697.

health-promotion lifestyle profile II. Public Health Nurs. 2000; 17: Quijano S, Navarro J. Un modelo integrado de motivacion en el

61–70. trabajo: conceptualizacion y medida [A comprehensive model of

Cooper E. Creating a culture of professional development: a mile- work motivation: conceptualization and measurement]. Rev.

stone patway tool for registered nurses. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2009; Psicol. Trab. Organ. 1998; 14: 193–216. (in Spanish).

40: 501–508. Quijano S, Navarro J, Cornejo JM. Un modelo integrado de com-

Crook TR, Todd SY, Combs JG, Woehr DJ, Ketchen DJ Jr. Does promiso e identificación con la organización: análisis del cuestion-

Human Capital matter? A meta-analysis of the relationship ario ASH-ICI [An integrated model of commitment and

between Human Capital and firm performance. J. Appl. Psychol. identification with the organization: analysis of the questionnaire

2011; 96: 443–456. ASH-ICI]. Rev. Psicol. Soc. Apl. 2000; 10: 27–61. (in Spanish).

Dugan J, Lauer E, Bouquot Z, Dutro B, Smith M, Widmeyer G. Romeo M, Berger R, Yepes M, Guardia J. Equivalent validity of

Stressful nurses: the effect on patient outcomes. J. Nurs. Care Qual. identification-commitment-inventory (HSA-ICI). Psycol. Writings

1996; 10: 46–58. 2011a; 4: 1–8.

EFQM. Introducing Excellence. Brussels: EFQM, 2007. Romeo M, Yepes M, Berger R, Guardia J, Castro C. Identification–

EFQM. Business Excellence Matrix. User Guide. EFQM Model 2010 commitment inventory (ICI model): confirmatory factor analysis

Version. Brussels: EFQM, 2010. and construct validity. Qual. Quant. 2011b; 45: 901–909.

ENOP. European Curriculum in W&O Psychology Reference Model Shaw CD. External quality mechanisms for health care: summary of

and Minimal Standards. March 2005. [Cited 7 Oct 2012.] Available the ExPeRT project on visitatie, accreditation, EFQM and ISO

from URL: http://www.ucm.es/info/Psyap/enop/rmodel.html. assessment in European Union countries. Int. J. Qual. Health Care

Ford JK, MacCallum RC, Tait M. The application of exploratory 2000; 12: 169–175.

factor-analysis in applied psychology – a critical review and analy- Shaw CD. Accreditation in Europe healthcare. Jt. Comm. J. Qual.

sis. Pers. Psychol. 1986; 39: 291–314. Patient Saf. 2006; 32: 266–275.

Generalitat de Catalunya. Acreditació de centres d’atenció hospi- Shaw CD, Kutryba B, Braithwaite J, Bedlicki M, Warunek A. Sus-

talària aguda a Catalunya. Manual de l’avaluador. [Accreditation tainable healthcare accreditation: message from Europe in 2009.

of acute inpatient care centers in Catalonia. Evaluators Manual]. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2010; 22: 341–350.

Barcelona: Generalitat de Catalunya. Departament de Salut, 2007; United States Agency for Health Care Research and Quality.

(in Catalan). The Effect of Health Care Working Conditions on Patient Safety.

© 2012 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd.

234 M. Yepes-Baldó et al.

Summary, Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. Report no. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Advancing nursing home quality

74.Rockville, MD: United States Agency for Health Care through quality improvement itself. Health Aff. 2010; 29: 81–

Research and Quality, 2003 86.

Vallejo P, Saura RM, Sunol R, Kazandjian V, Ureña V, Mauri J. A Yepes M. El constructo psicosocial de calidad de los procesos y recur-

proposed adaptation of the EFQM fundamental concepts of excel- sos humanos. Desarrollo teórico y validación empírica [The psy-

lence to health care based on the PATH framework. Int. J. Qual. chosocial construct of quality of processes and human resources.

Health Care 2006; 18: 327–335. Theoretical development and empirical validation]. [Disertation]

Veillard J, Champagne F, Klazinga N, Kazandjian V, Arah OA, 2010 (in Spanish). [Cited 3 Apr 2012.] Available from URL: http://

Guisset AL. A performance assessment framework for hospitals: hdl.handle.net/10803/77653.

the WHO regional office for Europe PATH project. Int. J. Qual. Ying L, Kunaviktikul W, Tonmukayakal O. Nursing competency

Health Care 2005; 17: 487–496. and organizational climate as perceived by staff nurses in a

Watts MD. Certification and clinical ladder as the impetus for pro- Chinese university hospital. Nurs. Health Sci. 2007; 9: 221–

fessional development. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 2010; 33: 52–59. 227.

© 2012 Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd.

También podría gustarte

- Research On Measuring Human Capital Factors - An Example of Household Sewing Machine Industry in TaiwanDocumento9 páginasResearch On Measuring Human Capital Factors - An Example of Household Sewing Machine Industry in Taiwanasad ullahAún no hay calificaciones

- Role - of - Abdul Ali - Empowerment - in - Organiza PDFDocumento8 páginasRole - of - Abdul Ali - Empowerment - in - Organiza PDFasad ullahAún no hay calificaciones

- Kardigap PDFDocumento16 páginasKardigap PDFasad ullahAún no hay calificaciones

- Dr. Jameel (IMS)Documento3 páginasDr. Jameel (IMS)asad ullahAún no hay calificaciones

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2104)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- Lecture-4 (Ch. 3, Zikmund-Theory Building)Documento18 páginasLecture-4 (Ch. 3, Zikmund-Theory Building)Kamran Yousaf AwanAún no hay calificaciones

- Develop Your CompetenciesDocumento62 páginasDevelop Your Competenciesmineasaroeun100% (1)

- Tech Lesson PlanDocumento6 páginasTech Lesson Planapi-312828959Aún no hay calificaciones

- Passion Roadmap LargeDocumento2 páginasPassion Roadmap LargeAshleyAún no hay calificaciones

- Running Head: Unconscious Mind 1Documento12 páginasRunning Head: Unconscious Mind 1wafula stanAún no hay calificaciones

- Sciencedirect: Nayereh ShahmohammadiDocumento6 páginasSciencedirect: Nayereh ShahmohammadikamuAún no hay calificaciones

- Goal Setting WorksheetDocumento4 páginasGoal Setting WorksheetSabrina MagnanAún no hay calificaciones

- Lacan Objet Petit ADocumento9 páginasLacan Objet Petit ALorenzo RomaAún no hay calificaciones

- Parent InterviewDocumento3 páginasParent Interviewapi-305278212Aún no hay calificaciones

- Advaita Practicing in Daily LifeDocumento3 páginasAdvaita Practicing in Daily LifeDragan MilunovitsAún no hay calificaciones

- Epc 4406 TP 4a MST-MCT Report MawadaDocumento7 páginasEpc 4406 TP 4a MST-MCT Report Mawadaapi-380948601Aún no hay calificaciones

- Maslach Burnout Inventory EnglishDocumento2 páginasMaslach Burnout Inventory EnglishAdrian Teodocio EliseoAún no hay calificaciones

- Teaching SimulationsDocumento30 páginasTeaching SimulationsMauricio Rojas Rodriguez (Docente)Aún no hay calificaciones

- "Wings of Desire" (Wim Wenders)Documento1 página"Wings of Desire" (Wim Wenders)dogukanberkbilge1903Aún no hay calificaciones

- CHAPTER 14: Assessment and Evaluation in Health Education: Name: Samielle Alexis G. Garcia Section: 7Documento2 páginasCHAPTER 14: Assessment and Evaluation in Health Education: Name: Samielle Alexis G. Garcia Section: 7Heinna Alyssa GarciaAún no hay calificaciones

- Sociological Perspective of Spouse Behaviour and Its Effects On Academic Performance of StudentsDocumento94 páginasSociological Perspective of Spouse Behaviour and Its Effects On Academic Performance of StudentsDaniel ObasiAún no hay calificaciones

- Art Appreciation Activity 1Documento2 páginasArt Appreciation Activity 1Erichelle EspineliAún no hay calificaciones

- Association For Psychological Science, Sage Publications, Inc. Psychological ScienceDocumento8 páginasAssociation For Psychological Science, Sage Publications, Inc. Psychological SciencesimineanuanyAún no hay calificaciones

- Krav Maga Psicoloy DefenceDocumento15 páginasKrav Maga Psicoloy DefenceSerena Icejust100% (4)

- 1 Lesson Plan Revision Clothes JobsDocumento4 páginas1 Lesson Plan Revision Clothes JobsNataliaAún no hay calificaciones

- Teaching Techniques Teach Your Child BetterDocumento17 páginasTeaching Techniques Teach Your Child BetterDiana MoralesAún no hay calificaciones

- LEADERSHIP FILE Kajal NainDocumento32 páginasLEADERSHIP FILE Kajal NainPooja SharmaAún no hay calificaciones

- Exam in Oral CommunicationDocumento5 páginasExam in Oral CommunicationKrissha Mae MinaAún no hay calificaciones

- SupervisionDocumento21 páginasSupervisionObeng Kofi Cliff0% (1)

- Red Flags For AutismDocumento3 páginasRed Flags For AutismHemant KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Plato's Understanding On RealityDocumento1 páginaPlato's Understanding On RealityWella Lou JardelozaAún no hay calificaciones

- Social and Emotional LearningDocumento15 páginasSocial and Emotional LearningIJ VillocinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Parenting A Dynamic Perspective 3nbsped 1506350429 9781506350424Documento814 páginasParenting A Dynamic Perspective 3nbsped 1506350429 9781506350424Fiola ArifajAún no hay calificaciones

- Trauma Jurnal UKMDocumento12 páginasTrauma Jurnal UKMezuan wanAún no hay calificaciones

- Dramatism of Kenneth Burke: Guilt-Redemption Cycle GuiltDocumento2 páginasDramatism of Kenneth Burke: Guilt-Redemption Cycle GuiltPatricia San PabloAún no hay calificaciones