Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

(2004) Comprehension Strategy Instruction in The Primary Grades

Cargado por

Nathália QueirózTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

(2004) Comprehension Strategy Instruction in The Primary Grades

Cargado por

Nathália QueirózCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Proof, Practice, and Promise: Comprehension Strategy Instruction in the Primary Grades

Author(s): Katherine A. Dougherty Stahl

Source: The Reading Teacher, Vol. 57, No. 7 (Apr., 2004), pp. 598-609

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the International Reading Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20205406 .

Accessed: 28/06/2014 15:33

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Wiley and International Reading Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The Reading Teacher.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.50 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 15:33:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

KATHERINE A. DOUGHERTY STAHL

Proof, practice, and promise:

strategy instruction

Comprehension

in the primary grades

This article reviews the research on hension strategy instruction for K-2 students and to

make recommendations for teachers regarding

comprehension strategy instruction in the which instructional can be used with

techniques

primary grades (K-2) and makes confidence may need to be used more

and which

cautiously they lack empirical

because support.

recommendations for teachers. The preliminary literature review involved

computerized searches of Educational Research

Until recently, I believed thatmy job as a InformationCenter (ERIC) and PsychLit databases

or second-grade

first- teacher was to de

for quantitative and qualitative studies of compre

velop fluent readers with the ability to de hension strategy instruction in primary classrooms.

code novel text automatically. This would put them

I also used the reference sections of these articles to

in good stead for comprehension instruction in the

find other studies involving primary students. All of

intermediate grades. This is no longer enough. The

the studies reviewed for this article involved stu

U.S. First grants will

sup

government's Reading dents in grades K-2. Some studies cited in this re

port literacy instructionin kindergarten through view did not have control groups.

third grade that includes systematic and explicit

instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, flu

ency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

The abundance of research in the primary The role of comprehension

to phonological awareness and

grades relating strategies

makes those aspects of a program

phonics fairly Comprehension strategies can be important to

easy to define and substantiate. However, more re a reader because to provide

they have the potential

cently theorists have demonstrated that even the access to knowledge that is removed from person

youngest readers need

opportunities to be "code al experience. The unstated is that children

premise

breakers, meaning makers, text users and text crit who actively in particular strate

engage cognitive

ics" (Muspratt, Luke, & Freebody, 1997). Less re gies (activating prior knowledge,

predicting, organ

search has been conducted on young children and a

izing, questioning, summarizing, creating

using texts to acquire new knowl mental are to understand and recall

comprehending, image) likely

edge, and critiquing texts. more of what they read. Strategies can be tools in

There is a research base to support comprehen the assimilation, refinement, and use of content. It

sion instruction in the

early primary grades, is assumed that as children practice these strate

of the research on reading compre and

although most gies in a group setting, they will habituate them

hension instruction has been conducted with third transfer them to other appropriate settings inde

grade and up (National Institute of Child Health pendently.

and Human 2000). The purpose of The keys to children's acquisition of compre

Development,

this article is to review that research on compre hension strategies are the instructional techniques

? 2004 International Reading Association (pp. 598-609)

598

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.50 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 15:33:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

used by the teacher. Most models of strategy in hension strategy instruction in the primary grades

struction incorporate teaching of declarative (see Table).

knowledge, procedural knowledge, and condition

1. Strategy instruction that is substantiated by

al knowledge (Duffy, 1993; Paris, Lipson, & research and widely practiced

Wixson, 1983). Declarative knowledge involves

2. Strategy instruction that is substantiated by

teaching the children what the strategy is.

research but less widely practiced

Instruction to use the strategy develops pro

in how

3. Strategy instruction that is not substantiated

cedural knowledge, and instruction in when the

is most useful not consti by research but widely practiced

strategy (or applicable)

4. Strategy instruction that has not been re

tutes conditional knowledge.

searched with novice readers and is not

Effective strategy instruction also uses a grad

widely used but may hold promise based on

ual release of responsibility (Pearson & Gallagher,

other evidence

1983). In this model, teachers begin instruction

with explicit teaching and guided practice. Over

time the responsibility for cognitive decision mak

ing and putting strategies into practice is released Substantiated by research and

to the students.

Research has demonstrated that comprehen

widely practiced

There is a base of research conducted in the

sion strategy instruction can enhance the reading

primary grades that supports

teaching story ele

comprehension of novice readers. I categorized the and

ments, Question-Answer Relationships,

use of strategies by teachers based on the review Substantial evidence indi

Reciprocal Teaching.

of literature, informal interactions with teachers, cates that teacher questioning can play a key role in

classroom and reports by preservice

observations, enhancing student comprehension. Over the years

teachers participating in field experiences. This these practices have gained wide acceptance by

process yielded four general categories of compre classroom teachers.

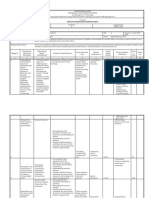

APROACHESINTHEPRIMARYGRADES

COMPREHENSION

Strong research base in primary grades

Widely used by teachers Guided/instructed retelling

Story maps

Teacher-generated questions

Question-Answer Relationships

Reciprocal Teaching

Limited use by teachers Targeted activation of prior knowledge

Text Talk

Directed Reading-Thinking Activity

Literature webbing

Visual imagery training

Video

Transactional Strategy Instruction

Currently lacking a research base in primary grades

Widely used by teachers Selection of main idea

K-W-L

Picture walk

Limited use by teachers Student-generated questions

Summarization

Proof, practice, and promise: Comprehension strategy instruction in the primary grades 599

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.50 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 15:33:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

all retelling scores were generally

Text structure Although low,

the story mapping groups were able to provide

Text structure studies with younger children

retellings that were somewhat more complete and

have typically involved listening comprehension or a

well-formed than the children who had not re

combination of listening and reading narrative texts

ceived story map instruction.

(Baumann & Bergeron, 1993; Mandler & Johnson,

Thus, the evidence about the effectiveness of

1977;Morrow, 1984a, b; Stein & Glenn, 1979).

using story maps in primary grades is positive but

Much of the research dealing with instruction in text

limited. (No studies involving students below third

structure uses visual representations, such as graph

ic organizers or story maps, to form a visual repre grade were included in the 2000 report of the

sentation of the text's organization.

NationalReading Panel.) Even though these meth

ods are included in basal readers and commonly

Researchers have defined and empirically test

used in classrooms in a guided or group format,

ed story grammars (Mandler & Johnson, 1977;

little is known about the capabilities of young chil

Stein & Glenn, 1979). There are differences among

dren to formulate full retellings and independent

story grammars but most share major similarities.

completion of story maps or specific teaching

The well-structured story includes a setting (char

strategies that are likely to foster these abilities.

acters, time, and place), an initiating event, the de

velopment of single or multiple episode systems

(reaction to the initiating event, goals, attempts, Teacher-generated questions

outcomes), and an ending or resolution. In primary Question answering and question-answering

classrooms, are used frequently to visu instruction can lead to an improvement in memory

story maps

for what was read, improvement in finding infor

ally represent the story grammar.

Several treatment studies guided children in in mation in text, and deeper processing of text

creasing their awareness of story structure through (McKeown & Beck, 2003; Menke & Pressley,

retelling,questioning strategies, or story maps. 1994; National Institute of Child Health and

Morrow (1984a) found that the listening compre

Human Development, 2000; Pressley & Forrest

1985; Taylor, Pearson, Walpole, & Clark,

hension of kindergartners improved when they par Pressley,

a a variety of questions, lower level

ticipated in directed reading activity that included 1999). Asking

the teacher asking questions about story structure and higher level, is important in prompting think

elements before and after reading. Morrow ing at all levels of reading development (Pressley &

(1984b)

also determined that comprehension Forrest-Pressley; Taylor et al., 1999). Raphael's

improved

when kindergartners were coached in retelling the (1984) instructional intervention, Question-Answer

elements. This sug (QAR), can support students in

story around story grammar Relationships

gests that guiding retellings and questioning thinking about questions generated by teachers or

around story structure elements is likely to improve others. QAR teaches students to consider and use

the listening comprehension of emergent readers the information in text and their personal knowl

to questions a

and listeners. Low achievers may need more ex edge when responding surrounding

instruction. like the five-finger text they have read. Four question types described

plicit Techniques

a concrete means for fos by Raphael incorporate these information sources

retelling might provide

tering the inclusion of story structure elements with (1986).

young children. In the five-finger retelling each fin Right There answers are found in a single

ger is used as a prompt to tell about a particular sto sentence in the text.

ry element (characters, setting, problem, plot, or Think and Search an

This can be taught with a poster as a Putting It Together

resolution). swers must be found across sections of text.

reminder.

that sto Author and You answers require the reader to

Baumann and Bergeron (1993) found

infer the meaning from the text because the

rymap instruction influenced the ability of first

the most answer to the question is not stated explicitly.

graders to successfully identify important

elements and their to respond to story On My Own answers rely on the reader's ex

story ability

element questions at statistically significant levels. perience and knowledge.

600 The Reading Teacher Vol. 57, No. 7 April 2004

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.50 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 15:33:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A series of studies determined that students in suggest others. The student leader leads the group

grades 2 through 8 could benefit from instruction in in clarifying any impediments to comprehension.

QAR (Ezell, Hunsicker, Quinqu?, & Randolph, Then the leader summarizes the text and predicts

1996; Ezell, Kohler, Jarzynka, & Strain, 1992, what is likely to come next. The process continues

Raphael, 1984). These studies determined that stu for each section of text, followed by discussion led

dents at all ability levels could benefit from in by a different student. Reciprocal Teaching has

struction in QAR. Average and below-average been used effectively with all grade levels, with

readers reap the greatest benefits when required to good and poor readers, and in small-group and

answer Right There, Think and Search, and Author whole-group contexts (Rosenshine & Meister,

and Me questions. QAR instruction was of little 1994).

Palincsar found re

help with On My Own questions that required (1988, 1991) ambiguous

more background about a topic. The sults for Reciprocal Teaching with first graders. In

knowledge

effect was true for high-ability students the earlier study, she found that Reciprocal

opposite

for whom acted as a tool for making Teaching used with teacher read-alouds did not im

QAR impor

tant connections between text and their more ex prove comprehension. However, she found that

tensive base. They made the greatest many of the teachers did not "buy into" the pro

knowledge

gains in correctly answering On My Own ques gram and were not carrying it out as suggested. In

tions. Younger students seem to need more time a second study, with teachers committed to

and practice in becoming familiar with QAR Reciprocal Teaching, she found that it did signifi

cantly improve She concluded that

(Raphael, 1984). Effects of the technique are main comprehension.

Reciprocal Teaching was effective in first grade as

tained over time and are effective with both narra

tive and expository text (Ezell et al., 1996). long as the teachers were committed to the effort

needed to implement the program.

The questions that teachers ask and instruction

Novice readers are likely to require develop

in QAR or other teacher-led questioning can act as

mental accommodations, as described by Sharon

a springboard and amodel for critical thinking and

Craig, a first-grade teacher (Coley, DePinto, Craig,

complex student-generated questions. Teacher-led

& Gardner, 1993; Marks et al., 1993). She spent

questioning can be a powerful vehicle in moving

three months teaching her students the individual

text interactions toward higher levels of thinking

and critical literacy. strategies before introducing the dialogue proce

dure. The children engaged in the dialogue after

reading several pages of text, usually a narrative.

Reciprocal Teaching The teacher assigned a role to each group member.

Reciprocal Teaching (Palincsar & Brown, The children their questions,

prepared summary,

1984) is an instructional activity that takes place or prediction with a partner and the teacher before

during reading with the purpose of gaining mean joining the discussion group. They jotted their

ing from text and self-monitoring. The teacher and ideas on a card to prepare for the discussion. First

students engage in a discussion about a segment were able to successfully in

graders engage

of text structured by four strategies: summarizing, with modifications.

Reciprocal Teaching Craig's

and predicting as suc

questioning, clarifying, (Palincsar, Craig evaluated the children's participation

1991; Palincsar & Brown, 1984; Palincsar, David, cessful on the basis of informal observation, but no

& Brown, 1992). Initially the teacher models each formal or quantitative evidence is pre

qualitative

of these strategies individually for the students. sented et al., 1993; Marks et al., 1993).

(Coley

After the strategies have been modeled, the stu

dents take turns leading the discussion about each

of text. The student leader facilitates a

segment

that focuses on the four

Substantiated by research but less

dialogue strategies.

Typically, the students read a segment of text. Then widely practiced

a student discussion leader asks a question about In this section, I review comprehension strate

the important information in the text, and the other gy instruction that has been conducted and proven

students answer the question and are encouraged to effective in improving comprehension in the

Proof, practice, and promise: Comprehension strategy instruction in the primary grades 601

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.50 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 15:33:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

primary grades. Due to a number of reasons, these Directed Reading-Thinking Activity (DR-TA) or

practices do not show up as regularly in classrooms Directed Listening-Thinking Activity (DL-TA). In

or professional development as the procedures in a DR-TA lesson the teacher and students make a

the previous section. Primary teachers can use the read a section of

prediction, justify the prediction,

comprehension strategy instructional techniques text, verify and discuss the text, and make a new

described in this section with confidence to expand then continue the procedure

prediction, through

their instructional out the text (Stauffer, have con

repertoire. 1969). Studies

firmed the effectiveness of the DR-TA with novice

Targeted discussion of background readers (Baumann & Bergeron, 1993; Baumann,

knowledge Seifert-Kessell, & Jones, 1992; Reutzel &

Currently the evidence indicates that young Hollingsworth, 1991; Stahl, 2003).

children rely heavily on background in Despite the age of DR-TA, the procedure has

knowledge

their interactions with text. young readers several components that recent studies have associ

Helping

activate relevant background information is an im ated with higher levels of achievement (Gaskins,

portant support, but as teachers we must be sensitive Anderson, Pressley, Cunnicelli, & Satlow, 1993;

to dialogue that indicates that a child may be relying McKeown & Beck, 2003; National Institute of

on inaccurate or irrelevant knowledge. We want in Child Health and Human Development, 2000;

struction that will help children learn to use prior Taylor, Pressley, & Pearson, 2002). DR-TA proce

knowledge effectively tomake specific connections dures tend to demand high levels of thinking by

to text, and teaching strategies that will help them and verification of predic

requiring justification

navigate multiple genres of text about which they tions (National Institute of Child Health and

may have limited background knowledge. Human Development; Taylor et al.). Both the stu

Beck and McKeown's (2001; McKeown & dents and the teacher initiate the conversations

Beck, 2003) work with interactive read-alouds in

(Gaskins et al.; Taylor et al.). Tangential informa

kindergarten and first grade

actually limits discus tion rarely enters the conversations, because the

sion of background knowledge to fit tightly around occur immediately

conversations before or after

the topic of the text. In studies leading to develop

reading a section of text (McKeown & Beck). The

ment of Text Talk, the read-aloud procedure, they immediate interaction around the text promotes

found that extensive discussions of the students'

consistent engagement, clarifies confusions, and

prior knowledge often

led the youngsters far from

provides a vehicle for creating an accurate repre

the text and what was recalled was based on shared

sentation of text as well as assimilation with prior

recollections rather than the text. The lesson com

knowledge (Gaskins et al.).

ponents of Text Talk, targeted prereading discus

sion and open-ended questioning during the

increase the students' reliance on the Literature webbing

read-aloud,

text in both understanding and recalling the text Literature webbing is a prediction technique

(McKeown & Beck). Text Talk also emphasizes the that has been demonstrated to be effective with

development of meaning vocabulary. first graders using predictable, narrative texts. The

teacher writes the events of the book on cards (or

Directed Reading-ThinkingActivity uses pictures) and mixes them up. The children

is directly related to read all of the cards and predict the order of events

The strategy of prediction

the activation of prior knowledge and familiarity by placing the cards in clockwise order around the

with narrative or nonnarrative structures. A predic web. The teacher reads the book to the children.

tion activity may take a variety of instructional Afterward, the teacher and children return to the

forms. in a classroom, the teacher en web to confirm or correct their predictions based

Typically,

the children a

in dialogue that promotes the on the reading. The children have an opportunity

gages

of a prediction or series of predictions. to read their own copy of the book with the

generation

Later the children verify the predictions from the teacher. Later, additional information is added to

text reading. Instruction might take the form of a the web through discussion about (a) text-to-text

602 The Reading Teacher Vol. 57, No. 7 April 2004

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.50 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 15:33:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

connections, (b) responses to the book, and (c) ex incorporated seamlessly with an existing classroom

tensions to other reading-writing activities. program by teachers, while yielding student im

Reutzel and Fawson (1991) found that first provement in reading comprehension.

grade readers using the webbing procedure read the

text with higher percentages of accuracy and were Video

also more successful in answering specific ques The use of video has recently been explored

tions about the text than a control group. Reutzel as a means of skills.

bootstrapping literacy

andHollingsworth (1991) determined that literacy Children with limited literacy backgrounds and

also had a positive influence on the use at

webbing young children may have difficulty sustaining

of story structure elements in the formulation of tention on the type of lengthier, complex that

story

predictions and the completeness of a story is necessary for comprehension instruction. The

retelling. richness of video as a medium and its familiarity

to children has made it an effective tool in the de

Visual imagery velopment of a visual representation, especially for

Visual instruction to help

seems young at-risk readers with limited literacy back

imagery

store Goldman, Varma, and Cognition

young readers and older, poor comprehenders grounds. Sharp,

and retrieve information they have read. Older, and Technology Group atVanderbilt (1999) found

readers may not benefit from this strat that the use of video to tell a lengthy, complex sto

competent

use of more to was more for at

egy due to their independent complex ry kindergartners advantageous

and retrieval risk students than those not at risk. In a retelling,

organizational systems.

instruction in visualization uses those at-risk students who were introduced to the

Typically,

some standard procedures to evoke images (Center, story via video retold nearly twice as many state

Freeman, Robertson, & Outhred, 1999; Gambrell ments as the children who only heard the story and

& Jawitz, 1993; Gambrell & Koskinen, 2002). viewed illustrations. In a measure

question-answer

demonstrated for

Center et al. incorporated visualization training as kindergartners greater memory

a the presented information, as well as

part of listening lesson for second-year students story greater

whose scores on a listening comprehension meas understanding of causal relationships. The use of

ure were in the bottom third of their school video enables students to engage with higher level

group.

On Day 1 of the training, students discussed and thinkingwhile developing competency with print

of sev based skills. Video may be a powerful tool that has

practiced "painting a picture in their minds"

the potential to act as a bridge between the world of

eral common objects that were on display. Then the

teacher used a think-aloud to demonstrate how to experience and the world of formal school learn

make a mental picture of a sentence. Teacher and ing and symbolic language systems. The challenge

in a classroom is to find quality videos or comput

student think-alouds surrounding target sentences

er technology that can be used as a link to texts and

opened the next six lessons. The techniques were

also generalized to the listening to provide instruction that enables young children

comprehension

to make to text comprehension.

passage for the day. The last five lessons simply bridges

consisted of reminders to use visualization tech

niques and the reasons for doing so during the nar Transactional Strategy Instruction

rative listening lesson. Extensive discussion always Transactional Strategy Instruction (TSI) is a

surrounded the students' images and their explicit term used to describe a body of comprehension

links to the text. The children receiving visualiza strategy instruction practices (e.g., Schuder, 1993).

tion training outperformed the control group on Instruction is transactional in three senses: (1)

measures of listening comprehension, reading readers link the text to prior knowledge; (2)mean

comprehension, and a retelling measure. This ing construction reflects the group and differs

demonstrated that children

performing below the from personal interpretations; and (3) the dynam

expected level benefit from visualization training. ics of the group determine the responses of all

The simplicity of the training procedures and members, including the teacher. TSI is long term,

reminders enable visualization training to be and the strategies act as the vehicle for text

Proof, practice, and promise: Comprehension strategy instruction in the primary grades 603

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.50 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 15:33:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

discussions. The programs also use a gradual improvement (Brown & Coy-Ogan, 1993; Coley

release of

responsibility instructional model et al, 1993; Duffy, 1993; Marks et al., 1993).

(Pearson & Gallagher, 1983) in order to foster in

dependent, self-regulating readers.

Evidence collected on TSI indicates that strat

Not substantiated by research

egy repertoire programs can be successful with

novice readers. The Students Achieving

butwidelypracticed

Independent Learning (SAIL) program used TSI While it is important to incorporate strategy in

with struggling readers in second grade. Listening struction that has been proven effective with young

and reading comprehension strategies were taught children, it is equally important to use caution and

explicitly during reading and content area instruc deliberation when incorporating comprehension in

tional periods. Ten strategies were included in the structional procedures with little or no research

repertoire: (1) setting purposes, (2) activating and base. Isolated identification of main ideas, K-W-L,

using prior knowledge, (3) getting the gist, (4) us and picture walks are popular instructional tech

ing text structure, (5) making and verifying pre niques. These teaching techniques may be effective

dictions, (6) generating questions, (7) creating in addressing particular teaching goals. However,

mental images and graphic representations, (8) at this time there is no research base substantiating

summarizing, (9) using think-alouds, and (10) us their effectiveness for improving the reading com

ing problem-solving (fix-up) strategies (Brown & prehension of novice readers.

Coy-Ogan, 1993; Schuder, 1993). A great deal of the research seems to agree

Brown, Pressley, Van Meter, and Schuder that even preschool-age children recall main ideas

(1995) followed the progress of 60 students who and ignore trivia when retelling stories they have

started second grade reading below grade level. heard (Sulzby, 1985) or stories they have seen on

The students were in five paired SAIL or tradition video (van den Broek, 2001). However, investiga

al classrooms. At the end of the year, the students in tions of the activities in basal reader series re

the SAIL classrooms showed more growth than the vealed that students were most frequently assigned

students in the traditional classrooms on a wide low-level tasks such as identifying a main idea

variety of measures. During a strategy interview, with a simple mark, perhaps underlining or select

SAIL students reported using more comprehension ing one of multiple choices (Baumann, 1984;

and word-level strategies. First-grade standardized Miller & Blumenfeld, 1993). Because of the limi

word skill and comprehension tests were given to tations of main idea activities in basal readers,

both groups. Statistically significant differences teachers are advised to design their own opportu

on word skill tests, comprehension tests, and year nities for observing and discussing the selection or

ly gains favored the SAIL group. generation of the important ideas in a variety of

There do seem to be some issues surrounding texts for a variety of purposes. These activities

comprehension repertoire programs that deserve should be constructed in response to the children's

attention and additional research. The manipulation needs and might range from the simple selection

and flexible use of multiple strategies is cognitive of a stated main idea and the supporting details in

ly demanding of students. The cost of these cogni a picture or paragraph (Baumann, 1984) to discus

tive demands may be too high for younger, sions surrounding more complex views of the main

disfluent readers (Sinatra, Brown, & Reynolds, idea, such as note-taking or studying for a test.

2002). The complexity of the process also makes Social interactions around specific texts could cen

it especially difficult to negotiate in a classroom ter on the lure of seductive

details, variations of im

(Duffy, 1993;El-Dinary & Schuder, 1993;Gaskins portance based on a variety of reading purposes,

et al., 1993). Some evidence indicates that experi background knowledge, or interest.

enced teachers may be better able to balance The K-W-L strategy was originally developed

process-content instruction than novice teachers by Ogle (1986) to enable teachers to access stu

(Gaskins et al.). Teachers report the evolution of dents' prior knowledge and to help them develop

their programs occurring over the course of two to their own purposes for reading expository text. The

three years, with continuous modifications for procedure is popular with teachers and students

604 The Reading Teacher Vol. 57, No. 7 April 2004

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.50 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 15:33:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

(Stahl, 2003). However, there is a surprising pauci what, where, when, why, and how) or generic ques

ty of research investigating K-W-L procedures. The tion stems (How are_and_alike? What is

studies involving students in the primary grades the main idea of_? How is_related to

were not able to substantiate the effectiveness of _? is it important that_?) were most

Why

K-W-L on measures of comprehension, metacog successful with the youngest students. Using a sto

or content to develop questions was also

nition, acquisition (McLain, 1990; ry grammar model

Stahl). The absence of evidence supporting the use fairly effective. The least effective prompts were

of K-W-L does not mean it is ineffective, only that question types (QAR) and prompts surrounding the

it has not been proved to be effective. In light of main idea. These studies were conducted with old

its popularity with teachers and students, it seems er students. Itmakes sense that the least complex

important to have research that investigates this would be most effective with novice

procedures

practice both as it was originally conceived and as readers. However, evidence is needed in

empirical

executed in classrooms. this area.

The guided reading book introduction or pic

Currently, there do not seem to be any studies

ture walk is based on the work of Marie Clay and

that focus on teaching summarization skills to

her descriptions of an effective book introduction

novice readers. The current emphasis on informa

for novice readers (Clay, 1991) and has been ex

tional text and the writing process in the primary

tended by Fountas and Pinnell (1996). Picture this an area that beckons

grades make for further

walks are widely used in today's classrooms to ac

investigation. A strategy that has been used suc

tivate prior knowledge and generate predictions.

cessfully with older students and might be useful

In Taylor's (2002) extensive work with effective

with younger students is the Generating Inter

practice and school reform, she found that low

actions Between Schemata and Text (GIST) pro

performance classes more commonly used picture

cedure (Cunningham, 1982). In GIST, students

walks than high-performance classes. A recent

begin creating summaries for sentences using 15

study found that picture walks were effective in

spaces. The teacher gradually increases the amount

promoting fluency, but not comprehension (Stahl,

of text being summarized in the 15 spaces. GIST

2003). More research needs to be done on the use

is conducted as a whole-class procedure first, then

of this common procedure and its variations in

in small groups, and, finally, individually. This con

implementation.

crete, visual procedure may hold potential as a

summarization strategy for younger children.

Brown, Day, and Jones (1983) found that the use of

Promising strategy instruction limited spaces forced students to summarize and

Many comprehension strategies have been to levels of importance that had

display sensitivity

studied with older readers, but not with novices. not been displayed using other formats.

The value of student-generated questions and sum

marization in fostering engagement and aiding re

call has a research base, but the research has not

What does this mean for teachers?

actually been conducted in kindergarten through

second if we want to explicitly The research demonstrates that instruction in

grade. However,

teach from the very beginning, phonological awareness and decoding are not

comprehension

these instructional practices may be useful with enough if we want students to be able to read and

make sense of multiple genres for multiple

younger readers, especially with the developmental purpos

es. Teachers of the youngest readers can enhance

adaptations described here.

The review of 26 interventions comprehension instructionduring teacher read

by Rosenshine,

Meister, and Chapman (1996) revealed that the alouds using techniques like Text Talk. Teaching

most effective procedures for teaching students to students to activate relevant background knowl

generate their own questions seemed to be those edge, to filter irrelevant or inaccurate

background

that were most concrete and easy to use. Strategies knowledge, and then use the text to make meaning

that taught students the use of signal words (who, ful connections and to expand their existing

Proof, practice, and promise: Comprehension strategy instruction in the primary grades 605

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.50 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 15:33:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

knowledge base can be important steps leading to others. Question-Answer Relationships enable stu

independent reading comprehension. dents to consider and use both the information in

Videos can be used with children to bolster text and their personal knowledge when responding

limited background knowledge. They can also be to questions surrounding a text they have read

used to introduce complex themes or lengthy texts (Raphael, 1984, 1986).

in comprehension strategy programs, because lev reading, some form of retelling should be

After

eled readers and other texts designed for early read required. For the youngest children a five-finger

ers may lack the grist for high-level thinking. The retelling with adult coaching works well. Older

video might be followed by a combination of stu children can do this with a peer, especially if this

dent retelling, teacher questioning, and guided is a school goal that is developed in kindergarten

discussion. and early first grade. However, by the end of first

Teachers of more adept readers in late first grade children should have regular opportunities

grade, second grade, and third grade can feel confi to write their synopses and personal responses to

dent that beginning to work toward a multiple text. A story map, a frame, or some other appro

strategy approach, but starting with a focus on a priately structured graphic organizer can help scaf

few well-taught strategies, will benefit their stu fold this writing. However, research has not yet

dents. The strategies can be taught using the texts resolved many issues around the young child's

that are already in place in the classroom literacy ability to do this independently. So caution, explic

program. However, comprehension strategies it instruction, close monitoring, and a gradual re

should be matched to their usefulness in making lease of responsibility are required during this

and remembering the text. Literature web transition from an oral retelling to any form of

meaning

written I used the GIST suc

bing and story maps should be used with folk tales synopsis. procedure

or other stories that adhere closely to the compo cessfully to help second graders summarize infor

nents of a narrative text structure. The instruction mational text and to synthesize a story plot on a

of ideational prominence (main idea) and levels of story map. However, this instructional technique

importance should be matched with the reading of has not been empirically tested with young

informational texts, such as a unit on nature, that children.

might be found in a basal reader or constructed as a Because effective readers use a variety of

theme unit by the teacher. The strategies can be strategies to deal with troublesome text, teachers

connected to student reading, teacher read-alouds, may want to move toward a repertoire approach as

and student writing. they become more comfortable with strategy in

Teachers can feel confident that the use of the struction and its adaptation to the existing reading

Directed Reading-Thinking Activity to generate curriculum. Reciprocal Teaching and Transactional

and verify the Instruction both have a strong research

predictions, justify those predictions, Strategy

predictions after reading a section of text will result base in the primary grades. However, implementa

a

in close reading of text. Stauffer (1969) designed tion can be challenging and requires teacher com

the procedure for use with narrative and informa mitment that is more likely to occur after teachers

tional text. The teacher should push the children to have laid the groundwork for the instruction of the

higher levels of thinking using thought-provoking preliminary comprehension strategies.

prompts and questions. Recent studies have found Caution also is warranted in the use of K-W-L

that the most effective reading teachers

encourage and picture walks if the instructional objective is

responses and ver comprehension. When they use these techniques

high-level through questioning

bal scaffolding, whether as part of a DR-TA or an teachers must be deliberate in their intentions and

other form of text interaction (Taylor et al., 2002). in the type and amount of verbal scaffolding pro

Teachers should present prompts that force the stu vided. They must also be attentive to student inac

dents to address issues of theme; character devel curacies and misconceptions. The after-reading

opment; character motive; and connections to self, comprehension activities become extremely impor

world, and other texts. Young students benefit from tant in determining whether the student is able to

sources needed or information in

being taught to consider the answer accurately represent the message

to respond to questions generated by teachers or the text.

606 The Reading Teacher Vol. 57, No. 7 April 2004

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.50 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 15:33:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Center, Y., Freeman, L, Robertson, G., & Outhred, L (1999).

Closing comments The effect of visual imagery training on the reading and

The comprehension strategy research conduct listening comprehension of low listening comprehen

ed with novice readers indicates that there are ders in year 2. Journal of Research in Reading, 22,

instructional that can be incor 241-256.

many implications

in primary reading The ideas Clay, M.M. (1991). Introducing a new storybook to young

porated programs.

readers. The Reading Teacher, 45,264-273.

stated in this article enable teachers, literacy spe

Coley, J.D., DePinto, T., Craig, S., & Gardner, R. (1993). From

cialists, and other decision makers to make a good

college to classroom: Three teachers' accounts of their

start. However, there are still many unknown fac

adaptations of reciprocal teaching. The Elementary

tors. The demands of reading acquisition and lack School Journal, 94,255-266.

of automaticity are likely tomake the developmen Cunningham, J.W. (1982). Generating interactions between

tal needs of the novice reader different than those schemata and text. InJ.A. Niles (Ed.), New inquiries in

of the older readers that have been studied more ex reading: Research and instruction (pp. 42-47).

Rochester, NY: National Reading Conference.

tensively. Also, the adaptation of strategy instruc

Duffy, G. (1993). Rethinking strategy instruction: Four teach

tion into an already full primary literacy curriculum ers' development and their lowachievers' understanding.

poses an additional challenge. The motivation pro The Elementary School Journal, 93,231-247.

vided by the Reading First grants may improve El-Dinary, P.B., & Schuder, T. (1993). Seven teachers' ac

both reading instruction and what we know about ceptance of transactional strategies instruction during

us to be deliberate about com their first year using it. The Elementary School Journal,

reading by forcing

instruction from the very beginning. 94,207-219.

prehension

Ezell, H.K., Hunsicker, S.A., Quinqu?, M.M., & Randolph, E.

(1996). Maintenance and generalization of QAR reading

Stahl teaches at the University of Illinois at comprehension strategies. Reading Research and

Urbana-Champaiqn (395 Education Building, Instruction, 36,64-81.

Champaign, IL61820, USA). E-mail Ezell, H.K., Kohler, F.W., Jarzynka, M., & Strain, P.S. (1992).

Use of peer-assisted procedures to teach QAR reading

kaystahl@uiuc.edu.

comprehension strategies to third-grade children.

Education and Treatment of Children, 15,205-227.

References

Fountas, I.e., & Pinnell, G.S. (1996). Guided reading: Good

Baumann, J.F. (1984). The effectiveness of a direct instruc

first teaching for all children. Portsmouth, NH:

tion paradigm for teaching main idea comprehension.

Heinemann.

Reading Research Quarterly, 20,93-117.

Gambrell, L.B., & Jawitz, P.B. (1993). Mental imagery, text

Baumann, J.F., & Bergeron, B. (1993). Story-map instruction

illustrations, and children's story comprehension and

using children's literature: Effects on first graders' com recall. Reading Research Quarterly, 28,265-273.

prehension of central narrative elements. Journal of

Gambrell, L.B.,& Koskinen, P.S. (2002). Imagery:A strategy

Reading Behavior, 25,407-437. for enhancing comprehension. InC.C. Block & M. Pressley

Baumann, J.F., Seifert-Kessell, N., & Jones, L.A. (1992).

(Eds.), Comprehension instruction: Research-based prac

Effect of think-aloud instruction on elementary students' tices (pp. 305-318). New York: Guilford.

comprehension monitoring abilities. Journal of Reading Gaskins, I.W., Anderson, R.C., M., Cunicelli, E.r &

Pressley,

Behavior, 24,143-172. Satlow, E. (1993). Six teachers' dialogue during cogni

Beck, I.L.,& McKeown, M.G. (2001). Text talk: Capturing the tive process instruction. The Elementary School Journal,

benefits of read aloud experiences for young children.

93, 277-304.

The Reading Teacher, 55,10-35.

Goldman, S.R., Varma, K.O., Sharp, D., & Cognition and

Brown, A.L., J.D., & Jones, R.S. (1983). The

Day, develop Technology Group at Vanderbilt. (1999). Children's un

ment of plans for summarizing texts. Child Development,

derstanding of complex stories: Issues of representa

54,968-979. tion and assessment. InS.R. Goldman, A.C. Graesser, & P.

Brown, R., & Coy-Ogan, L. (1993). The evolution of transac van den Broek (Eds.), Narrative comprehension, causali

tional strategies instruction inone teacher's classroom.

ty, and coherence: Essays in honor of Tom Trabaso (pp.

The Elementary School Journal, 94,221-233. 135-160). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Brown, R., Pressley, M., Van Meter, P., & Schuder, T. (1995). Mandler, J.M., & Johnson, N.S. (1977). Remembrance of

A quasi-experimental validation of transactional strate things parsed: Story structure and recall. Cognitive

gies instruction with previously low-achieving second Psychology, 9,111-151.

grade readers (Reading Research Rep. No. 33). Athens, Marks, M., Pressley, M? Coley, J.D., Craig, S., Gardner, R.,

GA: National Reading Research Center. DePinto, T., & Rose, W. (1993). Three teachers' adaptations

Proof, practice, and promise: Comprehension strategy instruction in the primary grades 607

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.50 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 15:33:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

of reciprocal teaching incomparison to traditional recip Paris, S.G., Lipson, M.Y., & Wixson, K.K. (1983). Becoming a

rocal teaching. The Elementary School Journal, 94, strategic reader. Contemporary Educational Psychology,

267-283. 8,293-316.

McKeown, M.G., & Beck, I.L. (2003). Taking advantage of Pearson, P.D., & Gallagher, M.C. (1983). The instruction of

read-alouds to help children make sense of decontextu reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational

alized language. InA. van Kleeck, S.A. Stahl, & E.B. Bauer Psychology, 8,317-344.

(Eds.), On reading books to children (pp. 159-176). Pressley, M., & Forrest-Pressley, D. (1985). Questions and

Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. children's cognitive processing. InA.C. Graesser & J.B.

McLain, K.V.M. (1990, December). Effects of two compre Black (Eds.), The psychology of questions (pp. 277-296).

hension monitoring strategies on the metacognitive Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

awareness and reading achievement of third and fifth Raphael, T.E. (1984). Teaching learners about sources of

grade students. Paper presented at the National Reading information for answering comprehension questions.

Conference, Miami, FL. Journal of Readinq, 27,303-311.

Menke, DJ., & Pressley, M. (1994). Elaborative interrogation: Raphael, T. (1986). Teaching question-answer relationships,

Using "why" questions to enhance the learning from revisited. The Readinq Teacher, 39, 516-522.

text. Journal of Reading, 37,642-645. Reutzel, D.R., & Fawson, P. (1991). Literature webbing pre

Miller, S.D., & Blumenfeld, P. (1993). Characteristics of tasks dictable books: A prediction strategy that helps below

used for skill instruction in two basal reader series. The average, first graders. Readinq Research and Instruction,

Elementary School Journal, 94,33-45. 30,20-30.

Morrow, L.M. (1984a). Reading stories to young children: Reutzel, D.R., & Hollingsworth, P.M. (1991). Using literature

Effects of story structure and traditional questioning webbing for books with predictable narrative: Improving

strategies on comprehension. Journal of Reading young readers' prediction, comprehension and story

Behavior, 16,273-288. structure knowledge. Readinq Psycholoqy: An

Morrow, L.M. (1984b). Effects of storyretelling on young International Quarterly, 12,319-333.

children's comprehension and sense of story structure. Rosenshine, B., & Meister, C. (1994). Reciprocal teaching: A

InJ. Niles (Ed.), 33rd yearbook of the National Reading review of the research. Review of Educational Research,

Conference (pp. 95-100). Rochester, NY: National 64, 479-530.

Reading Conference. Rosenshine, B., Meister, C, & Chapman, S. (1996). Teaching

Muspratt, S., Luke, A., & Freebody, P. (1997). Constructing students to generate questions: A review of the inter

critical literacies. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton. vention studies. Review of Educational Research, 64,

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 181-221.

(2000). The report of the National Reading Panel. Schuder, T. (1993). The genesis of transactional strategies

Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assess instruction ina reading program for at-risk students. The

ment of the scientific research literature on reading and Elementary School Journal, 94,183-200.

its implications for reading instruction (NIHPublication Sinatra, G., Brown, K.J., & Reynolds, R.E. (2002).

No. 00-47699). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Implications of cognitive resource allocation for compre

Printing Office. hension strategies instruction. In C.C. Block & M.

Ogle, D.M. (1986). K-W-L:A teaching model that develops ac Pressley (Eds.), Comprehension instruction: Research

tive reading of expository text. The Reading Teacher, 39, based best practices (pp. 62-76). New York: Guilford.

564-570. Stahl, K.A.D. (2003). The effects of three instructional

Palincsar, A.S. (1988, April 5-9). Collaborating in the inter methods on the readinq comprehension and content ac

est of collaborative learning. Paper presented at the an quisition of novice readers. Unpublished doctoral dis

nual meeting of the American Educational Research sertation, The University of Georgia, Athens.

Association, New Orleans, LA. Stauffer, R.G. (1969). Directinq readinq maturity as a coqni

Palincsar, A.S. (1991). Scaffolded instruction of listening tive process. New York: Harper & Row.

comprehension with first graders at risk for academic Stein, N.L., & Glenn, CG. (1979). An analysis of story com

difficulty. InA.M. McKeough & J.L. Lupart (Eds.), Toward prehension inelementary school children. InR.O. Freedle

the practice of theory-based instruction (pp. 50-65). (Ed.), New directions in discourse processinq (pp.

Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. 53-120). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Palincsar, A.S., & Brown, A.L. (1984). Reciprocal teaching of Sulzby, E. (1985). Children's emergent reading of favorite

comprehension-fostering and comprehension-monitoring storybooks: A developmental study. Readinq Research

activities. Cognition and Instruction, 2,117-175. Quarterly, 20,458-481.

Palincsar, A.S., David, Y., & Brown, A.L. (1992). Using recip Taylor, B. (2002, July). The CIERA school chanqe project:

rocal teaching in the classroom: A guide for teachers. Supportinq schools as they translate research into prac

Ann Arbor, Ml: University of Michigan. tice to improve students' readinq achievement. Paper

608 The Reading Teacher Vol. 57, No. 7 April 2004

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.50 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 15:33:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

presented at the Third Annual Center for the supported characteristics of teachers and schools that

Improvement of Early Reading Achievement Summer promote reading achievement. In B.M. Taylor & P.D.

Institute, Ann Arbor, Ml. Pearson (Eds.), Teaching reading (pp. 361-374). Mahwah,

Taylor, B.M., Pearson, P.D., Walpole, S., & Clark, C. (1999). NJ: Erlbaum.

Schools that beat the odds (CIERAReport). Ann Arbor, van den Broek, P. (2001). Fostering comprehension skills in

Ml: Center for the Improvement of Early Reading preschool children. Paper presented at the Second

Achievement. Annual Center for the Improvement of Early Reading

Taylor, B.M., Pressley, M., & Pearson, P.D. (2002). Research Achievement Summer Institute, Ann Arbor, Ml.

What's everyone talking about?

"We attribute the decline in

"My nine students, seven of which

were ELL students, averaged 1.6 our office referrals?682 to 88 "My students have made

years of growth during the year."

in three years' time?to students significant growth influency,

now being able to read and accuracy, and comprehension

"

"

with this curriculum.

engage in their schoolwork.

"I am delighted to finally find

something that integrates all

that is necessary to teach "Some of my students

and spelling!" "Our students' SAT-9 have made over three

reading, writing,

scores for total reading years' growth!"

doubled from 1999

to 2000."

"Our data show that this

curriculum has produced an I ?hini I?C2FI

average student gain of two

years in one year's time.

"

A Literacy Intervention Curriculum

Two decades of research are paying off*

wwwJariguage-usa.net

SOPRIS

WEST

Educational Services

# Cali (800) 547*6747 or visit

Proven and Practical wwwsopr?swestxom

Proof, practice, and promise: Comprehension strategy instruction in the primary grades 609

This content downloaded from 185.31.195.50 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 15:33:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

También podría gustarte

- Reciprocal Teaching Procedures and Principles: Two Teachers' Developing UnderstandingDocumento20 páginasReciprocal Teaching Procedures and Principles: Two Teachers' Developing UnderstandingAryaUgiex'sAún no hay calificaciones

- Reciprocal TeachingDocumento18 páginasReciprocal Teachingbluenight99Aún no hay calificaciones

- Rps Reading For Academic PurposesDocumento9 páginasRps Reading For Academic PurposesElsy pranitaAún no hay calificaciones

- Rencana Perkuliahan Semester (RPS)Documento6 páginasRencana Perkuliahan Semester (RPS)afrilia kartikaAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is Reciprocal Teaching?Documento16 páginasWhat Is Reciprocal Teaching?api-232955942Aún no hay calificaciones

- Contemporary Teacher Leadership Assignment 1Documento28 páginasContemporary Teacher Leadership Assignment 1api-332411688100% (1)

- Contemporary Teacher Leadership Assessment 1Documento40 páginasContemporary Teacher Leadership Assessment 1api-435640774Aún no hay calificaciones

- 07 Reciprocal Teaching Powerful Hands On Comprehension Strategy PDFDocumento5 páginas07 Reciprocal Teaching Powerful Hands On Comprehension Strategy PDFMarisela ThenAún no hay calificaciones

- Contemporary Teacher Leadership Assessment 1 Ver1Documento28 páginasContemporary Teacher Leadership Assessment 1 Ver1api-355889713Aún no hay calificaciones

- Avaliação The Measurement of Student Engagement - A Comparative Analysis of Various MethodsDocumento20 páginasAvaliação The Measurement of Student Engagement - A Comparative Analysis of Various MethodsTiagoRodriguesAún no hay calificaciones

- Improving Student's Writing Skill by Using Crossword MediaDocumento40 páginasImproving Student's Writing Skill by Using Crossword MediaFachmy SaidAún no hay calificaciones

- Brown SarahDocumento87 páginasBrown SarahyeneAún no hay calificaciones

- Miakatar17432825 Contemporary Teacher Leadership Report Assignment 1Documento39 páginasMiakatar17432825 Contemporary Teacher Leadership Report Assignment 1api-408516682Aún no hay calificaciones

- CTL Assessment1Documento35 páginasCTL Assessment1api-357321063Aún no hay calificaciones

- Learning Outcomes:: Edition) - New York: Mcgraw-Hill. Practices. New York: Pearson Education IncDocumento13 páginasLearning Outcomes:: Edition) - New York: Mcgraw-Hill. Practices. New York: Pearson Education IncMuhammad Sulton RizalAún no hay calificaciones

- Using Small Group Discussion Technique in Teaching ReadingDocumento7 páginasUsing Small Group Discussion Technique in Teaching ReadingKiki PratiwiAún no hay calificaciones

- Modul SMK Kelas Xii Semester 2Documento21 páginasModul SMK Kelas Xii Semester 2Anonymous DSPDrcT100% (1)

- RPS ReadingDocumento11 páginasRPS ReadingNursalinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Standard 1Documento9 páginasStandard 1api-525123857Aún no hay calificaciones

- Sinambela Et Al. (2015) PDFDocumento17 páginasSinambela Et Al. (2015) PDFAji Ramadhan NAún no hay calificaciones

- s1 - Edla Unit JustificationDocumento8 páginass1 - Edla Unit Justificationapi-319280742Aún no hay calificaciones

- 75 Judul Skripsi Bahasa Inggris SpeakingDocumento7 páginas75 Judul Skripsi Bahasa Inggris SpeakingArif FadliAún no hay calificaciones

- Definition of Shared ReadingDocumento2 páginasDefinition of Shared ReadinghidayahAún no hay calificaciones

- Assessment1Documento29 páginasAssessment1api-380735835Aún no hay calificaciones

- CTL Assessment 1 - CulhaneDocumento82 páginasCTL Assessment 1 - Culhaneapi-485489092Aún no hay calificaciones

- Teachers Using Classroom Data WellDocumento194 páginasTeachers Using Classroom Data WellTony TranAún no hay calificaciones

- Introduction To Genre Based ApproachDocumento42 páginasIntroduction To Genre Based ApproachIndah Dwi Cahayany100% (1)

- Resume Jurnal Public Speaking - P14Documento29 páginasResume Jurnal Public Speaking - P14HIRARKI FACODAún no hay calificaciones

- Contemporary Teacher Leadership Ass1Documento27 páginasContemporary Teacher Leadership Ass1api-357663411Aún no hay calificaciones

- Fadhilah Nur Rohmah - Fitk PDFDocumento115 páginasFadhilah Nur Rohmah - Fitk PDFavitaAún no hay calificaciones

- CTL Report 2h 2019Documento41 páginasCTL Report 2h 2019api-408697874Aún no hay calificaciones

- SupportingSpecialEduc in Maınstream SchoolDocumento197 páginasSupportingSpecialEduc in Maınstream SchoolekvangelisAún no hay calificaciones

- Cordy J s206946 Ela201 Assignment2Documento18 páginasCordy J s206946 Ela201 Assignment2api-256832695Aún no hay calificaciones

- CTL Assignment 1 CompleteDocumento51 páginasCTL Assignment 1 Completeapi-357570712Aún no hay calificaciones

- Improving The Skills of Early Reading ThroughDocumento8 páginasImproving The Skills of Early Reading ThroughZulkurnain bin Abdul Rahman100% (3)

- Science: Lesson Plans OverviewDocumento22 páginasScience: Lesson Plans Overviewapi-372230733Aún no hay calificaciones

- Classroom TalkDocumento8 páginasClassroom Talkapi-340721646Aún no hay calificaciones

- Assignment 2Documento6 páginasAssignment 2api-414353636Aún no hay calificaciones

- Barret TaxonomyDocumento21 páginasBarret Taxonomymaya90Aún no hay calificaciones

- Annotation Standard 5Documento3 páginasAnnotation Standard 5api-355644351Aún no hay calificaciones

- Applying Indirect Strategies To The Four Language SkillsDocumento6 páginasApplying Indirect Strategies To The Four Language SkillsWahyu AsikinAún no hay calificaciones

- The Effect of Using Inquiry-Based Learning Method On Students' Writing Ability of Explanation TextDocumento159 páginasThe Effect of Using Inquiry-Based Learning Method On Students' Writing Ability of Explanation Textochay1806Aún no hay calificaciones

- English FPDDocumento8 páginasEnglish FPDapi-306743539Aún no hay calificaciones

- An Analysis of Teaching English To Tuna Grahita Students: Difficulties and ChallengesDocumento75 páginasAn Analysis of Teaching English To Tuna Grahita Students: Difficulties and ChallengesPutri PutriAún no hay calificaciones

- 2018 AppraisalDocumento12 páginas2018 Appraisalapi-307661948Aún no hay calificaciones

- RPP (Praktik Mengajar I) ListeningDocumento5 páginasRPP (Praktik Mengajar I) ListeningAhmad yaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Vocabulary Teaching in English Language TeachingDocumento4 páginasVocabulary Teaching in English Language TeachingAkuninekAún no hay calificaciones

- rtl2 Documentation 1 22Documento43 páginasrtl2 Documentation 1 22api-407999393Aún no hay calificaciones

- Assignment 1Documento54 páginasAssignment 1api-408471566Aún no hay calificaciones

- LAtihan Edit Background AcakDocumento4 páginasLAtihan Edit Background AcakTiara VinniAún no hay calificaciones

- National Literacy and Numeracy Diagnostic Tools ReportDocumento191 páginasNational Literacy and Numeracy Diagnostic Tools Reportapi-320408653Aún no hay calificaciones

- Deakin AtaDocumento52 páginasDeakin Ataapi-267433636Aún no hay calificaciones

- Rivera Kylie 110231567 Inclusive ProjectDocumento10 páginasRivera Kylie 110231567 Inclusive Projectapi-525404544Aún no hay calificaciones

- CTL ReportDocumento45 páginasCTL Reportapi-533984328Aún no hay calificaciones

- Part 1. Case Study and Universal Design For LearningDocumento13 páginasPart 1. Case Study and Universal Design For Learningapi-518571213Aún no hay calificaciones

- Proposal Kuliah Bahasa InggrisDocumento30 páginasProposal Kuliah Bahasa InggrisAgus Hiday AtullohAún no hay calificaciones

- Assignment Cover SheetDocumento13 páginasAssignment Cover Sheetapi-450589188Aún no hay calificaciones

- CSTP 3 Rogosic 4Documento10 páginasCSTP 3 Rogosic 4api-566253930Aún no hay calificaciones

- UMF Unit-Wide Lesson Plan TemplateDocumento10 páginasUMF Unit-Wide Lesson Plan Templateapi-510704882Aún no hay calificaciones

- Q & A Cheat SheetDocumento2 páginasQ & A Cheat SheetGeorge Kevin TomasAún no hay calificaciones

- 03.02 Farm Animal Spelling FINAL 2Documento15 páginas03.02 Farm Animal Spelling FINAL 2girija_varadharajanAún no hay calificaciones

- Look at Word PicturesDocumento5 páginasLook at Word PicturesNathália QueirózAún no hay calificaciones

- Learning DifficultiesDocumento212 páginasLearning DifficultiesNathália QueirózAún no hay calificaciones

- (2013) de Koning B. B., Van Der Schoot M.Documento27 páginas(2013) de Koning B. B., Van Der Schoot M.Nathália QueirózAún no hay calificaciones

- (1994) DROR - Mental Imagery and AgingDocumento13 páginas(1994) DROR - Mental Imagery and AgingNathália QueirózAún no hay calificaciones

- (2003) Picture Is Worth A Thousand WordsDocumento14 páginas(2003) Picture Is Worth A Thousand WordsNathália QueirózAún no hay calificaciones

- Adorno On EducationDocumento24 páginasAdorno On Educationintern980Aún no hay calificaciones

- KISR! Program Report: Yesterday, Today, and TomorrowDocumento17 páginasKISR! Program Report: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrowmichaelburke47Aún no hay calificaciones

- Guidance On How To Write A Research ProposalDocumento2 páginasGuidance On How To Write A Research ProposaltotongsAún no hay calificaciones

- Lexical ApproachDocumento16 páginasLexical ApproachZul Aiman Abd Wahab100% (1)

- Chapter Seven: Causal Research Design: ExperimentationDocumento29 páginasChapter Seven: Causal Research Design: ExperimentationJanvi MaheshwariAún no hay calificaciones

- Politeness Strategy in Obama InterviewDocumento88 páginasPoliteness Strategy in Obama Interviewreiky_jetsetAún no hay calificaciones

- SS3 - DissectingDocumento7 páginasSS3 - DissectingWendy TiedtAún no hay calificaciones

- ds11 Experimental Design Graph PracticeDocumento10 páginasds11 Experimental Design Graph Practiceapi-110789702Aún no hay calificaciones

- Hitler Youth LessonDocumento24 páginasHitler Youth Lessonapi-236207520Aún no hay calificaciones

- Media and Information Literacy DLPDocumento2 páginasMedia and Information Literacy DLPMike John MaximoAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 04Documento11 páginasChapter 04Rabia TanveerAún no hay calificaciones

- Sampling MethodsDocumento2 páginasSampling Methodsbabyu1Aún no hay calificaciones

- BHMUS Application FormDocumento4 páginasBHMUS Application FormNeepur GargAún no hay calificaciones

- Literary Analysis RubricDocumento1 páginaLiterary Analysis Rubricded43Aún no hay calificaciones

- Land & Water Management in Africa PDFDocumento111 páginasLand & Water Management in Africa PDFAnonymous M0tjyWAún no hay calificaciones

- Urban and Regional PlanningDocumento8 páginasUrban and Regional PlanningAli SoewarnoAún no hay calificaciones

- PS 101 Syllabus Fall 2013Documento10 páginasPS 101 Syllabus Fall 2013Christopher RiceAún no hay calificaciones

- Social LegislationDocumento10 páginasSocial LegislationRobert RamirezAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Work 2011 2016Documento10 páginasSocial Work 2011 2016Joseph MalelangAún no hay calificaciones

- Training & Development - HDFC Standart LifeDocumento57 páginasTraining & Development - HDFC Standart LifeSandhadi GaneshAún no hay calificaciones

- LEADERSHIP and CommunicationDocumento5 páginasLEADERSHIP and CommunicationAdeem Ashrafi100% (2)

- DLL Template A4 LandscapeDocumento1 páginaDLL Template A4 LandscapeLeoben GalimaAún no hay calificaciones

- Lesson Plan Letter SDocumento4 páginasLesson Plan Letter Sapi-317303624100% (1)

- Lifelong Learning ReportDocumento10 páginasLifelong Learning ReportRaymond GironAún no hay calificaciones

- A Roadmap To The Philippines' Future: Towards A Knowledge-Based EconomyDocumento32 páginasA Roadmap To The Philippines' Future: Towards A Knowledge-Based Economyjjamppong0967% (3)

- Culturally Relevant UsaDocumento14 páginasCulturally Relevant UsaNitin BhardwajAún no hay calificaciones

- 9701 s07 Ms 31Documento7 páginas9701 s07 Ms 31karampalsAún no hay calificaciones

- San Diego Quick Assessment of Reading AbilityDocumento8 páginasSan Diego Quick Assessment of Reading Abilityapi-253577989100% (2)

- Summary of Pavlov, Thorndike and Skinner's TheoriesDocumento2 páginasSummary of Pavlov, Thorndike and Skinner's TheoriesSittie Zainab ManingcaraAún no hay calificaciones

- Cs Engg III Year Syllabus 2015Documento112 páginasCs Engg III Year Syllabus 2015Ramki JagadishanAún no hay calificaciones