Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

4 - Will Robots Steal Our Jobs? The Potential Impact of Automation

Cargado por

stalkoaTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

4 - Will Robots Steal Our Jobs? The Potential Impact of Automation

Cargado por

stalkoaCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

4 Will robots steal our jobs?

The potential impact of automation

on the UK and other major economies1

Key points Furthermore new automation Introduction

technologies in areas like AI and

Our analysis suggests that up to 30% The potential for job losses due to

robotics will both create some totally

of UK jobs could potentially be at advances in technology is not a new

new jobs in the digital technology

high risk of automation by the early phenomenon. Most famously, the

area and, through productivity

2030s, lower than the US (38%) or Luddite protest movement of the early

gains, generate additional wealth

Germany (35%), but higher than 19th century was a backlash by skilled

and spending that will support

Japan (21%). handloom weavers against the

additional jobs of existing kinds,

mechanisation of the British textile

primarily in services sectors that

The risks appear highest in sectors industry that emerged as part of the

are less easy to automate. Industrial Revolution (including the

such as transportation and storage

(56%), manufacturing (46%) Jacquard loom, which with its punch

The net impact of automation on card system was in some respects a

and wholesale and retail (44%),

total employment is therefore forerunner of the modern computer).

but lower in sectors like health

unclear. Average pre-tax incomes But, in the long run, not only were there

and social work (17%).

should rise due to the productivity still many (if, on average, less skilled)

gains, but these benefits may not be jobs in the new textile factories but,

For individual workers, the key

evenly spread across income groups. more importantly, the productivity gains

differentiating factor is education.

For those with just GCSE-level from mechanisation created huge new

There is therefore a case for some wealth. This in turn generated many

education or lower, the estimated

form of government intervention to more jobs across the UK economy in the

potential risk of automation is as

ensure that the potential gains from long run than were initially lost in the

high as 46% in the UK, but this falls

automation are shared more widely traditional handloom weaving industry.

to only around 12% for those with

across society through policies like

undergraduate degrees or higher.

increased investment in vocational The standard economic view for most

education and training. Universal of the last two centuries has therefore

However, in practice, not all of these

basic income schemes may also be been that the Luddites were wrong

jobs may actually be automated for

considered, though these suffer about the long-term benefits of the

a variety of economic, legal and

from potential problems in terms new technologies, even if they were

regulatory reasons.

of affordability and adverse effects right about the short-term impact on

on the incentives to work and their personal livelihoods. Anyone putting

generate wealth. such arguments against new technologies

has generally been dismissed as believing

in the Luddite fallacy.

1 This article was written by Richard Berriman, a machine learning specialist and senior consultant in PwCs Data Analytics practice, and John Hawksworth,

chief economist at PwC. Additional research assistance was provided by Christopher Kelly and Robyn Foyster.

30 UK Economic Outlook March 2017

However, over the past few years, fears This debate was given added urgency The discussion is structured as follows:

of technology-driven job losses have in 2013 when researchers at Oxford

re-emerged with advances in smart University (Frey and Osborne, 2013) Section 4.1 What proportion of jobs

automation the combination of AI, estimated that around 47% of total US are potentially at high

robotics and other digital technologies employment had a high risk of risk of automation?

that is already producing innovations computerisation over the next couple

like driverless cars and trucks, intelligent of decades i.e. by the early 2030s. Section 4.2 Which industry sectors

virtual assistants like Siri, Alexa and and types of workers could

Cortana, and Japanese healthcare robots. However, there are also dissenting voices. be at the greatest risk of

Notably, Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn automation in the UK?

While traditional machines, including (OECD, 2016) last year re-examined the

fixed location industrial robots, replaced research by Frey and Osborne and, using Section 4.3 Why does the potential

our muscles (and those of other animals an extensive new OECD data set, came risk of job automation

like horses and oxen), these new smart up with a much lower estimate that only vary by industry sector?

machines have the potential to replace around 10% of jobs were under a high

our minds and to move around freely in risk3 of computerisation. This is based on Section 4.4 How does the UK compare

the world driven by a combination of the reasoning that any predictions of job to other major economies?

advanced sensors, GPS tracking systems automation should consider the specific

and deep learning, if not now then tasks that are involved in each job rather Section 4.5 What economic, legal and

probably within the next decade or two. than the occupation as a whole. regulatory constraints

Will this just have the same effects as might reduce automation

past technological leaps short term In this article we present the findings in practice?

disruption more than offset by long term from our own analysis of this topic,

economic gains or is this something more which builds on the research of both Section 4.6 What offsetting job

fundamental in terms of taking humans Frey and Osborne (hereafter FO) and income gains might

out of the loop not just in manufacturing and Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn automation generate?

and routine service sector jobs, but more (hereafter AGZ). We then go on to

broadly across the economy? What exactly discuss caveats to these results in terms Section 4.7 What implications might

will humans have to offer employers of non-technological constraints on these trends have for

if smart machines can perform all or automation and potential offsetting public policy?

most of their essential tasks better in job creation elsewhere in the economy

the future2? In short, has the Luddite (though this is much harder to quantify). Section 4.8 Summary and

fallacy finally come true? conclusions.

Further details of the methodology

behind our analysis in Sections 4.1-4.4

are contained in a technical annex at

the end of this article, together with

references to the other books and

studies cited.

2 Martin Ford, The Rise of the Robots (Oneworld Publications, 2015) is one particularly influential example of an author setting out this argument in detail.

3 In both studies, this is defined as an estimated probability of 70% or more. For comparability, we adopt the same definition of high risk in this article.

UK Economic Outlook March 2017 31

4.1 What proportion of Figure 4.1 What proportion of jobs are potentially at high risk of automation?

jobs are potentially at 50 47

high risk of automation?

% of potential jobs at high risk 40 38

35

In the present article, we start by

30

of automation

revisiting the sharply contrasting results 30

of FO and AGZ, who estimate respectively

that around 47% and 9% of jobs in the US, 20

and around 35%4 and 10% of jobs in

10

the UK are at high risk of automation 10 9

by, broadly speaking, the early 2030s

(see Figure 4.1). 0

UK US

The AGZ study explains the difference PwC FO AGZ

as the result of a shift from the occupation-

based approach of FO to the task-based Sources: PwC analysis; FO; AGZ

approach adopted in their own study.

In the original study by FO, a sample

of occupations taken from O*NET, Furthermore, the same occupation We first replicated the AGZ study findings,

an online service developed for the may be more or less susceptible to but then subsequently enhanced the

US Department of Labour, were hand- automation in different workplaces. approach through using additional data

labelled by machine learning experts as Using the same outputs from the FO and developing our own machine learning

strictly automatable or not automatable. study, AGZ conducted their analyses algorithm for identifying automation risk6.

Using a standardised set of features of on the recently compiled OECD PIAAC Our findings offer some support for AGZs

an occupation, FO were then able to use database that surveys task structures for conclusion that taking into account the

a machine learning algorithm to generate individuals across more than 20 OECD tasks required to be carried out within

a probability of computerisation across countries. This includes much more each workers occupation diminishes

US jobs, but crucially they generated detailed data on the characteristics of the proposed impact of job automation

only one prediction per occupation. both particular jobs and the individuals somewhat relative to the FO results.

By assuming the same risk in matching doing them than was available to FO. Nevertheless, we conclude that the

occupations, FO were also able to obtain particular methodology used by AGZ

estimates for the UK (other authors have While recognising the differences in over-exaggerated this mitigating

also applied this approach to derive approach, it is still surprising that AGZ effect significantly.

estimates for other countries). obtain results which differ so much

from those of FO, bearing in mind that

AGZ argue, drawing on earlier research they started from a similar assessment

by labour market economists such as of occupation-level automatability.

David Autor5, that it is not whole We therefore conducted our own

occupations that will be replaced by analyses of the same OECD PIAAC

computers and algorithms, but only dataset as used in the AGZ study.

particular tasks that are conducted

as part of that occupation.

4 Haldane (2015) cites a Bank of England estimate of around this level for the UK based on their version of the FO analysis. This is also in line with other estimates by FO

themselves for the UK.

5 For example, Autor (2015).

6 See Annex for technical details of the methodology used.

32 UK Economic Outlook March 2017

Figure 4.2 Potential jobs at high risk of automation by country Before exploring our results in more

detail, we want to stress one important

50 caveat that applies both to our results

and those of FO and AGZ. This is that

% of potential jobs at high risk

40 38 these are estimates of the potential

35

30

impact of job automation based on

of automation

30 anticipated technological capabilities

21 of AI/robotics by the early 2030s.

20 Not only is the pace of technological

advance, and so the timing of these

10 effects uncertain, but more importantly:

0

not all of these technologically

UK US Germany Japan

feasible job automations may occur

Sources: ONS; PIAAC data; PwC analysis in practice for the economic, legal

and regulatory reasons discussed

in Section 4.5 below; and

Specifically, based on our own preferred Intuitively, the main reason for this

methodology, we found that around is because the specific approach used even if these potential job losses do

30% of jobs in the UK are at potential by AGZ biased their results towards materialise, they are likely to be offset

high risk of automation and around jobs having only a moderate risk of by job gains elsewhere as discussed in

38% in the US. These estimates are automation, but we found that this was Section 4.6 below the net long-term

based on an algorithm linking more an artefact of their methodology effect on total human employment

automatability to the characteristics of than a true representation of the data could be either positive or negative.

the tasks involved in different jobs as (see Annex for more technical details

well as those of the workers doing them of why we reach this conclusion). Unfortunately, it is much more difficult

(e.g. the education and training levels to quantify the effects of these caveats,

required). Our estimates are somewhat Our algorithm could also be applied particularly at the industry level, in part

lower than the original estimates by FO, to other OECD countries in the PIAAC because the second one involves new

but still much closer to those than to the database. For the purpose of the current types of jobs being created that do not

9-10% estimates of AGZ (see Figure 4.1). article, we focus on the results for the even exist now. In contrast, we can try

UK, US, Germany and Japan7. We found to quantify and analyse the number of

that both the US and Germany have an jobs at potential high risk of automation

increased potential risk of job automation by country, industry sector and type of

compared to the UK, whilst Japan has a worker as discussed below. But, in

decreased potential risk of job automation interpreting these results, we should

(see Figure 4.2). These reasons for never lose sight of these two key caveats.

these differences are explore further

in Section 4.4 below.

7 We also produced estimates for South Korea, but the results both in aggregate and for particular industry sectors were very similar to those for Japan, so we do

not report them here for reason of space. AGZ also estimated very similar risks for Japan and South Korea, albeit with lower risk levels than our estimates due to

the different methodology they applied to essentially the same data set.

UK Economic Outlook March 2017 33

4.2 Which industry Figure 4.3 Potential jobs at high risk of automation by UK industry sector

sectors and types of

Total UK job automation 10.43

workers could be at the

greatest potential risk of Wholesale and retail trade 2.25

automation in the UK? Manufacturing 1.22

If, for the sake of illustration, we apply Administrative and support service 1.09

our 30% estimate from the previous

Transportation and stoage 0.95

section to the current number of jobs

in the UK8, then we might conclude Professional, scientific and technical 0.78

(subject to the caveats noted above)

that several million jobs could potentially Human health and social work 0.73

be at high risk of automation in the UK. Accomodation and food service 0.59

Broken down by industry, over half of

these potential job losses are in four key Construction 0.52

industry sectors: wholesale and retail

Public administration and defence 0.47

trade, manufacturing, administrative

and support services, and transport Information and communication 0.39

and storage (see Table 4.1 and Figure 4.3

for details). Financial and insurance 0.35

Education 0.26

Other 0.83

0 2 4 6 8 10 12

UK jobs at high risk of automation (millions)

Sources: ONS; PIAAC data; PwC analysis

8 In practice, the total number of jobs in the UK is likely to be higher by the early 2030s, which is the approximate date by which we (and FO/AGZ) assume these potential

job losses from automation might occur. But, since we do not have detailed job projections that far ahead, we present some illustrative estimates using current data

(for 2016) instead.

34 UK Economic Outlook March 2017

The magnitude of potential job losses by Figure 4.4 Potential impact of job automation by UK industry sector

sector is driven by two main components:

the proportion of jobs in a sector we 70

estimate to have potential high risk of

60 Transportation

automation, and the employment share of

% of potential jobs at high risk

and storage

that sector (see Figure 4.4 and Table 4.1).

of automation by sector

50

Manufacturing Wholesale

The industry sector that we estimate could and retail trade

face the highest potential impact of job 40 Administrative

and support service

Financial Public administration

automation is the transportation and 30

and insurance and defence

Accomm- Professional,

Information and odation

storage sector, with around 56% of jobs communication Construction and food

scientific

and technical

service

at potential high risk of automation. 20 Human health

and social work

However, this sector only accounts for

10 Education

around 5% of total UK jobs, so the

estimated number of jobs at potential high 0

risk is around 1 million, or around 9% 0 5 10 15 20

of all potential job losses across the UK. Employment share by sector (%)

Sources: ONS; PIAAC data; PwC analysis

Instead the highest potential impact on

UK jobs is in the wholesale and retail

trade sector, with around 2.3 million

jobs at potential high risk of automation Table 4.1 Employment shares, estimated proportion and total number of employees

at potential high risk of automation for all UK industry sectors

(22% of all UK jobs estimated to be at

high risk) given that this is the largest Industry Employment Job automation Jobs at high risk

single sector in terms of numbers of share (%) (% at potential of automation

employees. Manufacturing has a similar high risk) (millions)

proportion of current jobs at potential Wholesale and retail trade 14.8% 44.0% 2.25

high risk (46%), but lower total numbers Manufacturing 7.6% 46.4% 1.22

at high risk of around 1.2 million due to

Administrative and support services 8.4% 37.4% 1.09

it being a smaller employer. A further

Transportation and storage 4.9% 56.4% 0.95

0.7 million jobs could be at potential

high risk of automation in human health Professional, scientific and technical 8.8% 25.6% 0.78

and social work, but this is a much lower Human health and social work 12.4% 17.0% 0.73

proportion of all jobs in that sector Accommodation and food service 6.7% 25.5% 0.59

(around 17%). Construction 6.4% 23.7% 0.52

Public administration and defence 4.3% 32.1% 0.47

Information and communication 4.1% 27.3% 0.39

Financial and insurance 3.2% 32.2% 0.35

Education 8.7% 8.5% 0.26

Arts and entertainment 2.9% 22.3% 0.22

Other services 2.7% 18.6% 0.17

Real estate 1.7% 28.2% 0.16

Water, sewage and waste management 0.6% 62.6% 0.13

Agriculture, forestry and fishing 1.1% 18.7% 0.07

Electricity and gas supply 0.4% 31.8% 0.05

Mining and quarrying 0.2% 23.1% 0.01

Domestic personnel and self-subsistence 0.3% 8.1% 0.01

Total for all sectors 100% 30% 10.4

Sources: ONS for employment shares (2016); PwC estimates for last two columns using PIAAC data

UK Economic Outlook March 2017 35

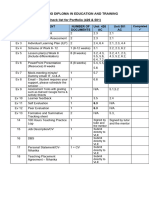

Which types of UK workers may be Table 4.2 Employment shares, estimated proportion and total number of employees

most affected by automation? at potential high risk of automation by UK worker characteristics

The potential impact of job automation Worker characteristics Employment Job automation Jobs at potential

also varies according to the characteristics share (%) (% at potential high risk of

of the workers. On average, we find that high risk) automation

men and, in particular, those with lower (millions)

levels of education (GCSE-level and Gender:

equivalent only or lower) are at greater risk

Female 46% 26% 4.1

of job automation. This is characteristic of

the sectors that are at highest estimated Male 54% 35% 6.3

risk. For example, the transportation and Education:

storage, manufacturing, and wholesale

and retail trade sectors have a relatively Low education (GCSE level or lower) 19% 46% 3.0

high proportion of low education Medium education 51% 36% 6.2

employees (34%, 22%, and 28%

High education (graduates) 30% 12% 1.2

respectively). Men also make up the great

majority of the workforce in the first two Sources: PwC estimates using PIAAC data

of these sectors (85% and 73%).

We also estimate that private sector

Table 4.3 Estimated proportion

employees and particularly those in of employees at potential high risk

SMEs are most at risk, which is linked of automation by UK employer

to variations in job and employee characteristics

characteristics (e.g. education and Employer Job automation

training levels required). characteristics (% at potential

high risk)

Public sector 22%

Private sector 34%

Employees:

<11 30%

11-1000 32%

1000+ 24%

Sources: PwC estimates using PIAAC data

36 UK Economic Outlook March 2017

4.3 Why does potential spend a much greater proportion of their

time engaged in manual tasks that require

risk of job automation physical exertion and/or routine tasks such

vary by industry sector? as filling forms or solving simple problems.

In contrast, in lower automation risk

Task composition industries such as education, there is an

One of the main drivers of a job being at increased focus on social and literacy skills,

potential high risk of automation is the as shown in Figure 4.5, which are

composition of tasks that are conducted. relatively less automatable9.

Workers in high automation risk industries

such as transport and manufacturing

Figure 4.5 Task composition for UK employees in transportation and storage, manufacturing, and education industry sectors

Transportation and storage Manufacturing Education

2% 2% 6% 11%

11% 12%

22% 20%

22%

20% 19% 27%

7% 33%

38% 13% 22%

12%

Compared to UK average (%) Compared to UK average (%) Compared to UK average (%)

Manual tasks 143 Manual tasks 131 Manual tasks 69

Routine tasks 127 Routine tasks 110 Routine tasks 90

Computation 59 Computation 108 Computation 96

Management 87 Management 81 Management 94

Social skills 68 Social skills 80 Social skills 144

Literacy skills 51 Literacy skills 64 Literacy skills 179

0 50 100 150 200 0 50 100 150 200 0 50 100 150 200

Sources: PIAAC data; PwC analysis

9 Although the considerable growth of e-learning shows that there is scope for automation in education, this may widen access to courses rather than replacing human

teachers altogether. For a discussion of how UK universities can prosper in a digital age, see this report:

https://www.pwc.co.uk/assets/pdf/the-2018-digital-university-staying-relevant-in-the-digital-age.pdf

UK Economic Outlook March 2017 37

Figure 4.6 Task composition comparison for UK employees in wholesale and retail trade, and human health and social work

industry sectors

Wholesale and retail trade Increased task share in human Human health and social work

health vs wholesale

2% 4%

14% 14%

18%

Manual tasks -3 18%

Routine tasks 0

Computation 0

Management -4

26% Social skills 4 31%

31% Literacy skills 3 22%

-10 -5 0 5 10

10% 10%

Sources: PIAAC data; PwC analysis

Worker and job characteristics Figure 4.7 Potential impact of job automation by education level for UK employees

Task composition of jobs is not, however, in wholesale and retail trade, and human health and social work industry sectors

the only driver of high automation risk. 60 57 56

In the two largest sectors by employment

share - wholesale and retail trade and 50

human health and social work - there are

high risk of automation

% of potential jobs at

broadly comparable task compositions 40

33

(see Figure 4.6). However, the proportion 30 28

of jobs at potential high risk of automation

is over 2.5x greater in the wholesale 20

15

and retail trade (44%) than for health 11

and social work (17%). 10

0

Instead differences in job requirements Low education Medium Education High education

are the main factors that cause the risk (GCSE level or lower) (graduates)

of automation to differ between these

Wholesale and retail trade Human health and social work

two sectors, mostly significantly as

regards education. Sources: PIAAC data; PwC analysis

On the whole, education requirements

are higher in the human health and

social work sector, with more than twice

the proportion of employees having high

education levels (i.e. degree level or

higher): 33% compared with 15% in

wholesale and retail. Health and social

work also has much lower proportions

of low education workers (i.e. GCSE

level or lower): 11% compared with 28%

in wholesale and retail (see Figure 4.7).

38 UK Economic Outlook March 2017

Table 4.4 Job characteristics for UK employees in wholesale and retail trade, 4.4 How does the UK

and human health and social work industry sectors compare to other major

Wholesale and Human health National economies?

retail trade and social work average

Required >1 year work experience 32% 48% 47% As shown in Figure 4.2 earlier in this

article, we estimate that there is a greater

High educational job requirements 14% 44% 33%

potential impact of job automation in the

More training required at work 14% 29% 21% US (38%) and Germany (35%) compared

Moderate/complex computer use at work 51% 61% 68%

to the UK (30%), but a decreased potential

impact in Japan (21%). As with the UK,

Feel challenged at work 11% 15% 12% the potential impact of job automation

Responsible for staff 30% 41% 35% in other countries is driven by the

industry composition of the country

Co-operate with others > 25% of the time 73% 77% 70%

(i.e. the employment shares across

Sources: PIAAC data; PwC analysis sectors) and the relative proportion of

jobs at high risk of automation in each

of those sectors. However, a greater

The difference in education levels is also The human health and social work sector proportion of the variation between

reflected in the job characteristics for also has a high proportion of employees countries is explained by differences in

employees in the health and social work (23%) in health professional or health the automatability of jobs within sectors.

sector. There is a much higher proportion associate professional occupations,

of employees that need work experience which have particularly low automation

prior to employment, have higher potential according to our methodology.

educational requirements in their Advances we have seen in recent years in

current role, and are engaged in Japan in healthcare robots might suggest

more training at work (see Table 4.4). some of these model estimates could

prove too low as this technology develops

A more detailed examination of the further and spreads to the UK, although

occupations in both sectors also reveals some of these may be working with

that a higher proportion of occupations in rather than replacing human workers.

health and social work are jobs that are far Similarly surgeons may be able to conduct

less automatable than in wholesale and operations remotely now using digitally-

retail trade. In particular, sales workers controlled robotics, but (at least for the

that comprise the majority of employment moment) we are some way from robot

share in the wholesale and retail trade surgeons carrying out operations unaided.

sector have twice the job automation

potential (38%) compared with personal

care workers in the human health and

social work sector (18%).

UK Economic Outlook March 2017 39

Why is the estimated risk of job Figure 4.8 Comparison of potential jobs at high risk of automation between UK

automation higher in the US than and US

the UK?

UK vs US

We find that the larger proportion of 50

jobs at potential high risk of automation high risk of automation

40 8 38

in the US is almost exclusively driven by

% of potential jobs at

differences in the automatability of jobs 30

30 0

for given industry sectors. The US has a

similarly service-dominated economy 20

to the UK with relatively little difference 10

in employment shares by industry sector

0

(see middle panel of Figure 4.8). However,

UK job Impact of industry Impact of US job

several important industry sectors automation composition automation automation

show significantly higher potential job

automation risks in the US than in the

US employment share relative to UK (%)

UK (see bottom panel in Figure 4.8).

Wholesale and retail trade -1

The most significant example here Manufacturing 0

is the financial and insurance sector, Administrative and support service 1

where automatability is assessed to be Transportation and storage -2

much higher in the US (61%) than the Professional, scientific and technical -2

UK (32%). Further analysis of the data Human health and social work 1

suggests that the key difference is related Accommodation and food service 2

to the average education levels of finance Construction 0

professionals being significantly higher Public administration and defence 0

in the UK than the US. This may reflect Information and communication 0

the greater weight in the UK of City of Financial and insurance 1

London finance professionals working in Education -1

international markets, whereas in the US Arts and entertainment 0

there is more focus on the domestic retail -40 -30 -20 -10 0 10 20 30 40

market and many more workers who do

not need to have the same educational

levels. The jobs of these US retail US job automatability relative to UK (%)

financial workers are assessed by our Wholesale and retail trade 3

methodology as being significantly more Manufacturing 6

routine and so more automatable then Administrative and support service -2

the average finance sector job in the UK, Transportation and storage 20

with its greater weight on international Professional, scientific and technical 7

finance and investment banking. Human health and social work 8

Accommodation and food service 19

Construction 11

Public administration and defence 1

Information and communication 18

Financial and insurance 29

Education 3

Arts and entertainment -5

-40 -30 -20 -10 0 10 20 30 40

Sources: PIAAC data; PwC analysis

40 UK Economic Outlook March 2017

Why is the estimated risk of job Figure 4.9 Comparison of potential jobs at high risk of automation between UK

automation higher in Germany and Germany

than the UK?

UK vs Germany

In Germany, by contrast, the greater 50

proportion of jobs at potential high risk

high risk of automation

of automation is driven by broadly

% of potential jobs at 40 3 35

2

similar sized impacts from both industry 30

30

composition and job automatability by

sector (see Figure 4.9). In particular, 20

Germany has a higher share of 10

employment in the manufacturing sector

0

than the UK, and manufacturing has

UK job Impact of industry Impact of German job

a relatively large proportion of jobs at automation composition automation automation

high risk of automation. At the individual

sector level, relative automatability

German employment share relative to UK (%)

levels are varied, but on average higher

in Germany. Wholesale and retail trade 0

Manufacturing 11

This is most marked for construction, Administrative and support service 0

where the proportion of jobs at high Transportation and storage -1

risk of automation is estimated at 41% Professional, scientific and technical -2

in Germany but only 24% in the UK. Human health and social work 1

The main difference is that for those Accommodation and food service -2

working in building and related trades Construction -1

in Germany, 60% of all tasks are either Public administration and defence -2

manual or routine, while in the UK these Information and communication -1

account for only 48% of tasks. Instead Financial and insurance 0

there is a greater proportion of time Education -3

spent on management tasks in the UK, Arts and entertainment -1

such as planning and consulting others, -40 -30 -20 -10 0 10 20 30 40

and those that require social skills such

as negotiating.

German job automatability relative to UK (%)

UK construction workers are therefore Wholesale and retail trade -2

classified as being less automatable on Manufacturing 2

average than their German counterparts. Administrative and support service -7

Any automation in the construction Transportation and storage 8

sector will require major advances in Professional, scientific and technical -4

mobile robotics by the early 2030s if our Human health and social work 7

estimates are to prove reliable. It is also Accommodation and food service 5

unclear here, as in many other sectors, Construction 17

how far these kind of construction Public administration and defence -3

robots will work alongside human Information and communication 2

workers, complementing and enhancing Financial and insurance 8

their productivity, rather than replacing Education 0

them totally. At the very least, there may Arts and entertainment -7

be a long-lasting intermediate stage in

-40 -30 -20 -10 0 10 20 30 40

the use of robots in construction and

other sectors involving manual tasks

outside tightly controlled factory or Sources: PIAAC data; PwC analysis

warehouse conditions.

UK Economic Outlook March 2017 41

Why is the estimated risk of job Figure 4.10 Comparison of potential jobs at high risk of automation between UK

automation lower in Japan than and Japan

the UK?

UK vs Japan

In Japan there is a lower proportion 50

of jobs at high risk of automation than high risk of automation

the UK, despite having an industry 40

% of potential jobs at

4 -13

composition that (like Germany) is 30

30

more focused on manufacturing, which 21

is one of the most automatable sectors. 20

However, this industry mix effect is 10

more than offset by the lower average

0

automatability of most individual

UK job Impact of industry Impact of Japan job

sectors in Japan relative to the UK, as automation composition automation automation

shown in Figure 4.10.

Japan employment share relative to UK (%)

One sector of particular interest because

of its high total employment level is the Wholesale and retail trade 2

wholesale and retail trade. In Japan, Manufacturing 10

the proportion of jobs at high risk of Administrative and support service 0

automation in this sector is estimated Transportation and storage 0

at only around 25% as compared to Professional, scientific and technical -4

around 44% in the UK Human health and social work -2

Accommodation and food service 0

For retail sales workers, we found that Construction 0

the lower proportion of jobs at high risk Public administration and defence -1

of automation in Japan is partly due to Information and communication 0

a lower proportion of time conducting Financial and insurance -1

manual tasks compared with Education -4

management tasks, such as planning or Arts and entertainment 0

organising. Perhaps linked to this, sales -40 -30 -20 -10 0 10 20 30 40

workers in Japan are far more likely

to need further training at work (60%

compared with 10%) and a significantly Japan job automatability relative to UK (%)

higher proportion feel challenged at Wholesale and retail trade -19

work (65% compared with 8%). Manufacturing -16

Administrative and support service -17

Whether these projections hold true Transportation and storage -23

in the longer run depends on whether Professional, scientific and technical -1

there are moves in Japan to change Human health and social work -6

the nature of retailing, making it less Accommodation and food service -7

labour-intensive on the US or UK model. Construction 2

This might involve customers doing Public administration and defence -16

more self-service in Japan than they Information and communication -8

do now, so reducing the need for skilled Financial and insurance -19

sales staff and increasing the need and Education -5

scope for automation. Arts and entertainment -1

-40 -30 -20 -10 0 10 20 30 40

Sources: PIAAC data; PwC analysis

42 UK Economic Outlook March 2017

4.5 What economic, Furthermore, a relatively flexible UK Legal and regulatory constraints

labour market that has been open to

legal and regulatory migration from the EU in particular has

Even if economic barriers to adopting

constraints might automation can eventually be overcome,

made it a comparatively attractive option however, there could also be significant

restrict automation in for companies in many sectors to expand legal and regulatory hurdles to negotiate.

practice? by hiring more people, rather than

incurring potentially large up-front In the case of driverless vehicles10,

So far the analysis has focused on the costs by investing in new technologies for example, the issue of who bears the

technical feasibility of automation based such as AI and mobile robots, which will liability for accidents is a difficult one

on the characteristics of the jobs also seem relatively risky as they may to resolve is it the car manufacturer,

(e.g. the tasks required to be done) and not have been widely tested in practice. the manufacturer of the sensors on the

their typical workers (e.g. education car, the provider of the computer software

levels). But, in practice, we recognise that Why take the risk of such investments that makes driving decisions, or some

actual future levels of job automation when there is a low risk, low cost human combination of these and other suppliers?

may fall below these levels or at least alternative? Such considerations would What about the liability of the human

take longer to reach them than we might apply in sectors like transport, retail and passenger if he or she is expected to take

expect on purely technological grounds. wholesale, hotels and restaurants, and manual control of the vehicle when

food processing. signalled to do so by the vehicles computer

Economic constraints but failed to do so? And should driverless

Over time, however, we would expect cars be expected to satisfy higher safety

The first important constraint here is

these economic factors to become less standards then human drivers if that is

economic just because it is technically

significant as the cost of the new digital one of their key selling points?

feasible to replace a human worker with

technologies falls (quite possibly very

a robot, for example, does not mean that

rapidly if a robotic version of Moores In the long run, we would expect these

it would be economically attractive to

Law turns out to apply) and they become kind of legal and regulatory barriers to

do so. This will depend on the relative

more widely adopted, leading them to be overcome in those industries where

costs of robots (including energy inputs,

seem less risky and untested by companies automation makes economic sense and

maintenance and repairs) relative to

that were not early adopters. But it remains is technically feasible. But there may

human workers, as well as their

highly uncertain in many sectors with often be powerful vested interests

relative productivity.

low current adoption of robots when the arguing against too rapid an advance

tipping point to much higher adoption in automation, so it may well be that

In recent years, we have seen rapid total

will be reached. Organisational inertia realisation of the full potential automation

employment growth in the UK, driven in

and legacy systems may push back the may occur significantly later than the

part by relatively subdued (or negative)

timing of any such shifts towards early 2030s timescale we assume in this

real wage growth.

automation even if they become report (in line with the original FO study).

technically and economically feasible.

10 For a more detailed discussion of these issues, see PwC Strategy&s 2016 Connected Car report here: http://www.strategyand.pwc.com/reports/connected-car-2016-study

UK Economic Outlook March 2017 43

4.6 What offsetting job The more significant offsetting factor is 4.7 What implications

that these new automated technologies

and income gains might will boost productivity considerably over

might these trends have

automation generate? time12 (if not, they will not be adopted on for public policy?

economic grounds). This will generate

Another key caveat noted earlier in this extra incomes, initially for the owners The latter point raises important public

article is that we have focused so far on of the intellectual and financial capital policy issues. The less controversial one

estimating the potential job losses from behind the new technologies, but feeding is that the government, working with

automation. In practice, however, there into the wider economy as this income employers and education providers,

should also be significant gains from is spent or invested in other areas. should invest more in the types of

these technologies in terms of: This additional demand will generate education and training that will be most

increased jobs and incomes in sectors useful to people in this increasingly

completely new types of jobs being that are less automatable, including automated world. Exactly how to identify

created related to these new digital healthcare and other personal services the skills that will be required and develop

technologies; and where robots may not be able to totally the training is much more complex of

replace, as opposed to complement and course for many people, this will involve

more significantly in quantitative enhance, workers with the human touch an increased focus on vocational training14

terms, the wealth from these for the foreseeable future13. that is constantly updated to stay one

innovations being recycled into step ahead of the robots. It also requires

additional spending, so generating The historical evidence suggests that this better matching of workers to the new

demand for extra jobs in less will eventually lead to: opportunities that will arise in an

automatable sectors where humans increasingly digital economy. But the

retain a comparative advantage broadly similar overall rates of principle of investing more in education,

over smart machines. employment for human workers, skills and retraining seems widely accepted.

although with different distributions

These offsetting gains are not easy to across industry sectors and types of Central and local government bodies also

quantify, but in an earlier PwC study11 jobs than now; needs to support digital sectors that can

with Carl Frey, we estimated that generate new jobs, for example through

around 6% of all UK jobs in 2013 were higher average real income levels place-based strategies centred around

of a kind that did not exist at all in 1990. across the country as a whole due university research centres, science parks

Moreover, in London, this proportion rose to higher overall productivity; and other enablers of business growth.

to around 10% of all jobs. These were This place-based approach is one of the

mostly related to new digital technologies but quite possibly also a more skewed key themes in the governments new

such as computing and communications. income distribution with a greater industrial strategy and its wider

Similarly, by the 2030s, 5% or more of UK proportion going to those with the devolution agenda. It also involves

jobs may be in areas related to new skills to thrive in an ever more digital extending the latest digital infrastructure

robotics/AI of a kind that do not even economy this would put a premium beyond the major urban centres to

exist now. It is very difficult to know not just on education levels when facilitate small digital start-ups in other

what these new types of jobs will be in entering the workforce, but also the parts of the country.

advance, but past experience suggests ability to adapt over time and reskill

that there will be some job gains from throughout a working life.

this source, albeit probably significantly

less than the around 30% potential job

losses from automation discussed above.

11 C. Frey and J. Hawksworth (PwC, 2015): http://www.pwc.co.uk/assets/pdf/ukeo-regional-march-2015.pdf

12 See, for example, this 2015 PwC report on the potential productivity benefits of service robots:

http://www.pwc.com/us/en/technology-forecast/2015/robotics/features/service-robots-big-productivity-platform.html

13 Of course, eventually, we may reach the science fiction scenario where robots become indistinguishable in all ways from humans. At present, that seems likely to be

much further off than the early 2030s time horizon we are focusing on in this study, though this could always change given recent rapid advances in AI and robotics.

14 An area where the UK lags well behind countries like Germany as highlighted in our 2016 Young Workers Index report here:

http://www.pwc.co.uk/services/economics-policy/insights/young-workers-index.html

44 UK Economic Outlook March 2017

More controversial is whether 4.8 Summary and The net impact of automation on total

governments should intervene more employment is therefore unclear. Average

directly to redistribute income15.

conclusions pre-tax incomes should rise due to the

In particular, the idea of a universal productivity gains, but these benefits will

Our analysis suggests that around 30%

basic income (UBI) has gained traction probably not be evenly spread across

of UK jobs could potentially be at high

in Silicon Valley and elsewhere as a income groups. The pay premium for

risk of automation by the early 2030s,

potential way to maintain the incomes higher education and non-automatable

lower than the US (38%) or Germany

of those who lose out from automation skills will also probably rise ever higher.

(35%), but higher than Japan (21%).

and (to be hard headed about it) whose

consumption is important to keep the There is therefore a case for some form

The risks appear highest in sectors such

economy going. The problem with UBI of government intervention to ensure

as transportation and storage (56%),

schemes, however, is that they involve that the potential gains from automation

manufacturing (46%) and wholesale

paying a lot of public money to many are shared more widely across society

and retail (44%), but lower in sectors

people who do not need it, as well as through policies in areas like education,

like health and social work (17%).

those that do. As such the danger is that vocational training and job matching.

such schemes are either unaffordable or Some form of universal basic income

For individual workers, the key

destroy incentives to work and generate scheme might also be considered though

differentiating factor is education.

wealth, or they need to be set too low this does face problems relating to

For those with just GCSE-level education

to provide an effective safety net. affordability and potential adverse

or lower, the estimated potential risk of

incentive effects that would need to

automation is as high as 46% in the UK,

Nonetheless, we are now seeing practical be addressed.

but this falls to only around 12% for those

trials of UBI schemes in a number of

with undergraduate degrees or higher.

countries around the world including

Finland, the Netherlands, some US

However, in practice, not all of these jobs

and Canadian states, India and Brazil.

may actually be automated for a variety of

The details of these schemes vary

economic, legal and regulatory reasons.

considerably, and it is beyond the scope

of this article to review them in depth,

Furthermore new technologies in areas

but it seems likely that more pilot schemes

like AI and robotics will both create some

of this kind will emerge around the world

totally new jobs in the digital technology

and that they will come on to the policy

area and, through productivity gains,

agenda in the UK as well. For the moment,

generate additional wealth and spending

the need to reduce the UK budget deficit

that will support additional jobs of

may be a significant barrier to any such

existing kinds, primarily in services

scheme on a national level, as well as

sectors that are less easy to automate.

concerns about the social acceptability

of giving people money for nothing.

But the wider question of how to deal

with possible widening income gaps

arising from increased automation

seems unlikely to go away.

15 Another idea here is the recent suggestion of Bill Gates to tax robots where these displace human labour. However, it is not clear that such a specific tax on investment in

robots would be economically efficient. Other labour-saving technologies do not face such specific taxes, so why single robots out for such treatment and potentially lose

productivity gains from such innovation and investment?

UK Economic Outlook March 2017 45

Annex

Technical details of our methodology

In the present study, we first recreated Figure 4.A1 Replication of the AGZ occupation-based approach

the dataset from Arntz, Gregory and

Zieharn (AGZ, 2016). This comprised 0.030

US data from the Programme for the

International Assessment of Adult 0.025

Estimated kernal density

Competencies (PIAAC) database,

0.020

merged with automatability data from

FO. However, these sources use different 0.015

occupation classifications: the 702 O*NET

occupations from FO were classified using 0.010

the Standard Occupational Classification

0.005

(SOC) 2010 codes, whilst the PIAAC

database contained occupations classified 0.0

using the first 2-digits from International 0 20 40 60 80 100

Standard Classification of Occupations Automatability (%)

(ISCO-08) codes. Occupation-based approach

To map the FO data with SOC codes Sources: PIAAC data; FO automatability data; PwC analysis

to the PIAAC data with ISCO-08 codes

we used cross-walks from the US Census

Bureau. This results in an expanded

Figure 4.A2 Replication of the AGZ task-based approach

dataset with many-to-one relationships

from the FO data to PIAAC data. As per 0.030

AGZ, each duplicated case in the expanded

dataset was assigned a weight that sums 0.025

Estimated kernal density

to unity for each individual.

0.020

We then replicated the Expectation- 0.015

Maximisation (EM) algorithm by AGZ

that iteratively: predicts the probability 0.010

of computerisation scores from FO

0.005

using a fractional logit model, and

then re-calculates the first weights 0.0

proportionally to the prediction 0 20 40 60 80 100

residuals (see AGZ for further details). Automatability (%)

Through this procedure we replicated

Task-based approach

the distribution of automatability in

the US from AGZ for the occupation- Sources: PIAAC data; FO automatability data; PwC analysis

based and task-based approaches

(see Figures 4.A1 and 4.A2 respectively).

46 UK Economic Outlook March 2017

However, we consider that the low Figure 4.A3 Re-simulated task-based approach

proportion of jobs with high automatability

(i.e. >70% risk of automation) in AGZs 0.030

task-based approach is an artefact of their

predictive model. To illustrate this we 0.025

re-simulated the EM algorithm from AGZ Estimated kernal density 0.020

using different sets of predictive features

(see Figure 4.A3). 0.015

As the feature set increases from feature 0.010

set 1 to feature set 3 and performance

0.005

metrics of the classifier improve, the

task-based approach curve shifts from 0.0

the centre to more closely match the 0 20 40 60 80 100

occupation-based approach distribution. Automatability (%)

Accordingly, the proportion of jobs Occupation-based approach Feature set 1 Feature set 2 Feature set 3

estimated to have high automatability

also increases. In other words, the more Sources: PIAAC data; FO automatability data; PwC analysis

predictive the model the higher the

estimation of high automatability jobs.

Figure 4.A4 EM method applied to cross-walk weights only

To improve the methodology we split

the analytics into two parts: an initial 0.030

application of the EM algorithm to only

0.025

re-weight the cross-walked dataset, and

Estimated kernal density

a second phase of building an enhanced 0.020

classifier algorithm. A re-simulation

of the task-based approach with the 0.015

EM method for weights only is shown

in Figure 4.A4. 0.010

0.005

The algorithm developed using the US

extended dataset was then applied to 0.0

the original US dataset and recalibrated 0 20 40 60 80 100

accordingly. This enhanced and Automatability (%)

recalibrated model could then be applied Occupation-based approach EM method for weights

to each of the other OECD countries.

The present report contains results for Sources: PIAAC data; FO automatability data; PwC analysis

the US, UK, Germany and Japan.

References

Arntz, M., T. Gregory and U. Zierahn (2016), The risk of automation for jobs in OECD countries: a comparative analysis, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No 189

Autor, D. H. (2015), Why are there still so many jobs? The history and future of workplace automation, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), pp.3-30.

Ford, M. (2015), The Rise of the Robots, Oneworld Publications.

Frey, C.B. and M.A. Osborne (2013), The Future of Employment: How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerization?, University of Oxford.

Frey, C.B. and J. Hawksworth (2015), New job creation in the UK: which regions will gain the most from the digital revolution?, PwC UK Economic Outlook, March 2015.

Available from: http://www.pwc.co.uk/assets/pdf/ukeo-regional-march-2015.pdf

Haldane, A. (2015) Labours share, speech to the TUC, London, 15 November 2015. Available from: http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/speeches/2015/864.aspx

PwC Strategy& Connected Car Report (2016). Available from: http://www.strategyand.pwc.com/reports/connected-car-2016-study

PwC Technology Forecast (2015), Service robots: the next big productivity platform.

Available from: http://www.pwc.com/us/en/technology-forecast/2015/robotics/features/service-robots-big-productivity-platform.html

PwC (2016), The 2018 digital university: staying relevant in a digital age.

Available here: https://www.pwc.co.uk/assets/pdf/the-2018-digital-university-staying-relevant-in-the-digital-age.pdf

PwC (2016), Young Workers Index: Empowering a new generation. Available here: http://www.pwc.co.uk/services/economics-policy/insights/young-workers-index.html

UK Economic Outlook March 2017 47

www.pwc.co.uk/economics

At PwC, our purpose is to build trust in society and solve important problems. PwC is a network of firms in 157 countries with more than 223,000 people who are

committed to delivering quality in assurance, advisory and tax services. Find out more and tell us what matters to you by visiting us at www.pwc.com/UK.

This publication has been prepared for general guidance on matters of interest only, and does not constitute professional advice. You should not act upon the information

contained in this publication without obtaining specific professional advice. No representation or warranty (express or implied) is given as to the accuracy or completeness

of the information contained in this publication, and, to the extent permitted by law, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, its members, employees and agents do not accept

or assume any liability, responsibility or duty of care for any consequences of you or anyone else acting, or refraining to act, in reliance on the information contained in

this publication or for any decision based on it.

2017 PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. All rights reserved. In this document, "PwC" refers to the UK member firm, and may sometimes refer to the PwC network.

Each member firm is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details.

The Design Group 31597 (03/17)

También podría gustarte

- Adda247-Bank PR - Yr.papers (2016-2021) 2022 EditionDocumento1162 páginasAdda247-Bank PR - Yr.papers (2016-2021) 2022 EditionRohith RàsçültAún no hay calificaciones

- Connected Manufacturing ReportDocumento36 páginasConnected Manufacturing ReportNgọc Khánh TrươngAún no hay calificaciones

- Organisational Behaviour PDFDocumento129 páginasOrganisational Behaviour PDFHemant GuptaAún no hay calificaciones

- AI and Automation in RetailDocumento24 páginasAI and Automation in RetailMirjana SeminarskiAún no hay calificaciones

- MGI Briefing Note AI Automation and The Future of Work June2018Documento7 páginasMGI Briefing Note AI Automation and The Future of Work June2018Guilherme RosaAún no hay calificaciones

- Card Format Homeroom Guidance Learners Devt AssessmentDocumento9 páginasCard Format Homeroom Guidance Learners Devt AssessmentKeesha Athena Villamil - CabrerosAún no hay calificaciones

- Foundation of EducationDocumento15 páginasFoundation of EducationShaira Banag-MolinaAún no hay calificaciones

- State of Phygital 2021Documento44 páginasState of Phygital 2021Alexander ZemlyakAún no hay calificaciones

- DLP HGP Quarter 2 Week 1 2Documento3 páginasDLP HGP Quarter 2 Week 1 2Arman Fariñas100% (1)

- WEF White Paper Technology Innovation Future of Production 2017Documento38 páginasWEF White Paper Technology Innovation Future of Production 2017CARLOS MUNIVE GARCÍAAún no hay calificaciones

- Global Economy and Market IntegrationDocumento6 páginasGlobal Economy and Market IntegrationJoy SanatnderAún no hay calificaciones

- PWC The Future of Financial ServicesDocumento27 páginasPWC The Future of Financial ServicesPhương TrầnAún no hay calificaciones

- World of Work in Developing Countries Future DriversDocumento9 páginasWorld of Work in Developing Countries Future DriversMIGUEL ANGELO BASUELAún no hay calificaciones

- Report - The Impact of New Technologies On Employment and The WorkforceDocumento26 páginasReport - The Impact of New Technologies On Employment and The Workforcerafaysmart007Aún no hay calificaciones

- No 286 CertezaDocumento2 páginasNo 286 CertezaRamon CertezaAún no hay calificaciones

- Could Artificial IntelligenceDocumento3 páginasCould Artificial IntelligencecandiceAún no hay calificaciones

- Learning Nation:: Equipping Canada'S Workforce With Skills For The FutureDocumento27 páginasLearning Nation:: Equipping Canada'S Workforce With Skills For The Futuremoctapka088Aún no hay calificaciones

- Capgemini Impacto Social de La Robótica y La AutomatizaciónDocumento7 páginasCapgemini Impacto Social de La Robótica y La AutomatizaciónJordi MaciasAún no hay calificaciones

- Discuss StsDocumento8 páginasDiscuss StsPrincess Julie Mae SaladoAún no hay calificaciones

- A Future That Works The Impact of Automation in Denmark PDFDocumento56 páginasA Future That Works The Impact of Automation in Denmark PDFMisin MongAún no hay calificaciones

- Artificial Intelligence Are We All Going To Be UnemployedDocumento5 páginasArtificial Intelligence Are We All Going To Be UnemployedMUHAMMAD CHAMDAN HUSEINAún no hay calificaciones

- Arrival of RobotDocumento1 páginaArrival of RobotParvezRana1Aún no hay calificaciones

- Finals ECONDEVDocumento28 páginasFinals ECONDEVNicolette EspinedaAún no hay calificaciones

- Mind The Gap WhitepaperDocumento12 páginasMind The Gap WhitepaperHomeAún no hay calificaciones

- PublicPaper Dorn PDFDocumento32 páginasPublicPaper Dorn PDFAnonymous 07vOE7U31LAún no hay calificaciones

- The Future of Manufacturing A New PerspectiveDocumento7 páginasThe Future of Manufacturing A New Perspectivecesar foreroAún no hay calificaciones

- UNIT 9 - Computers in The WorkplaceDocumento13 páginasUNIT 9 - Computers in The Workplacevicrattlehead2013Aún no hay calificaciones

- Kearney Hamilton Project Work in Machine Age February 2015 FINALDocumento8 páginasKearney Hamilton Project Work in Machine Age February 2015 FINALJeremyAún no hay calificaciones

- Db-History Suggests AI Will Create Not Destroy JobsDocumento13 páginasDb-History Suggests AI Will Create Not Destroy JobsTevfik ErenAún no hay calificaciones

- What 800 Executives Envision For The Postpandemic WorkforceDocumento7 páginasWhat 800 Executives Envision For The Postpandemic WorkforceBusiness Families FoundationAún no hay calificaciones

- Innovate Into The 5G EraDocumento8 páginasInnovate Into The 5G EraGary CrawfordAún no hay calificaciones

- The Automation Readiness Index 2018Documento33 páginasThe Automation Readiness Index 2018reinarudoAún no hay calificaciones

- Pro Worker AI Policy Memo20Documento14 páginasPro Worker AI Policy Memo20s2826754401Aún no hay calificaciones

- 3-WEF FOJ Executive Summary JobsDocumento12 páginas3-WEF FOJ Executive Summary JobsBasura00Aún no hay calificaciones

- MGI-Jobs-Lost-Jobs Gained-Executive-summary-December 4-2017Documento28 páginasMGI-Jobs-Lost-Jobs Gained-Executive-summary-December 4-2017eyaoAún no hay calificaciones

- Geoforum 115 (2020) 120-131Documento12 páginasGeoforum 115 (2020) 120-131Ngọc Linh NguyễnAún no hay calificaciones

- Science 2013 Bonvillian 1173 5Documento3 páginasScience 2013 Bonvillian 1173 5renonoAún no hay calificaciones

- So Many Jobs, So Few Qualified Workers - Fixing The Education Disconnect - InternationalDocumento16 páginasSo Many Jobs, So Few Qualified Workers - Fixing The Education Disconnect - InternationalRicardo Sage2 HarrisAún no hay calificaciones

- Acemoglu 2023 Can We Have Pro Worker AIDocumento13 páginasAcemoglu 2023 Can We Have Pro Worker AIporota loverAún no hay calificaciones

- Implicaciones A Largo Plazo de La Revolución de Las TIC Aplicación de Las Lecciones de La Teoría Del Crecimiento y La Contabilidad Del CrecimientoDocumento15 páginasImplicaciones A Largo Plazo de La Revolución de Las TIC Aplicación de Las Lecciones de La Teoría Del Crecimiento y La Contabilidad Del CrecimientoAkira Shiroma YaipenAún no hay calificaciones

- CC106 ReviewerDocumento5 páginasCC106 ReviewerMimi DamascoAún no hay calificaciones

- The World of Technology: However, at A Lesser Extent, It Affects Job NegativelyDocumento2 páginasThe World of Technology: However, at A Lesser Extent, It Affects Job NegativelyShaina Marie B. AugustoAún no hay calificaciones

- Automation & AI - How Machines Are Affecting People and PlacesDocumento108 páginasAutomation & AI - How Machines Are Affecting People and PlacesShirinda PradeeptiAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Study 1Documento2 páginasCase Study 1Milljan Delos ReyesAún no hay calificaciones

- BENANAV - A World Without Work?Documento9 páginasBENANAV - A World Without Work?Tiago BrandãoAún no hay calificaciones

- Busness FinalsDocumento7 páginasBusness FinalsericAún no hay calificaciones

- BCG - The Future of Jobs in The Era of AI - 2021 - NeiDocumento40 páginasBCG - The Future of Jobs in The Era of AI - 2021 - NeiHevertom FischerAún no hay calificaciones

- Is This Time Different - RP - 2019 - PubDocumento10 páginasIs This Time Different - RP - 2019 - PubTrần KhangAún no hay calificaciones

- Paper 12 PDFDocumento19 páginasPaper 12 PDFDevika ToliaAún no hay calificaciones

- Paper 12 PDFDocumento19 páginasPaper 12 PDFDevika ToliaAún no hay calificaciones

- Topic SteeplDocumento16 páginasTopic SteeplAsad UllahAún no hay calificaciones

- The European Dimension of The Digital EconomyDocumento7 páginasThe European Dimension of The Digital EconomyHải Yến NguyễnAún no hay calificaciones

- Topic SteeplDocumento13 páginasTopic SteeplAsad UllahAún no hay calificaciones

- E1 - McKinsey - Technology 2018Documento29 páginasE1 - McKinsey - Technology 2018lucasAún no hay calificaciones

- Modernisation Theory: A 60 Second Guide To - .Documento1 páginaModernisation Theory: A 60 Second Guide To - .Ronie Enoc SugarolAún no hay calificaciones

- TNO - Connecting Changing Accelerating - TNO Strategy 2022 - 2025 - CompressedDocumento104 páginasTNO - Connecting Changing Accelerating - TNO Strategy 2022 - 2025 - CompressedJosue FamaAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is The Future of WorkDocumento5 páginasWhat Is The Future of Worked matsuAún no hay calificaciones

- Chap 5 - Fostering The Economic and Social Benefits of ICT PDFDocumento10 páginasChap 5 - Fostering The Economic and Social Benefits of ICT PDFsandhya eshwarAún no hay calificaciones

- Digital Infrastructure Management ChallengesDocumento4 páginasDigital Infrastructure Management ChallengesFarah LimAún no hay calificaciones

- DIAZ, TORRENSModelacion de Las Relaciones Entre Empleo Industrial e Informacion y Tecnologia de ComunicacionDocumento5 páginasDIAZ, TORRENSModelacion de Las Relaciones Entre Empleo Industrial e Informacion y Tecnologia de ComunicacionAnonymous lAUAvlAún no hay calificaciones

- Newsletterelac18eng enDocumento12 páginasNewsletterelac18eng enStartup AcademyAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is ProductivityDocumento5 páginasWhat Is ProductivitySatakshi SinghAún no hay calificaciones

- Educating The Industry 4.0 WorkforceDocumento3 páginasEducating The Industry 4.0 WorkforceDhillukshanAún no hay calificaciones

- Digital Risk Governance: Security Strategies for the Public and Private SectorsDe EverandDigital Risk Governance: Security Strategies for the Public and Private SectorsAún no hay calificaciones

- Conclusion and RecommendationsDocumento3 páginasConclusion and Recommendationsstore_2043370333% (3)

- Stem Whitepaper Developing Academic VocabDocumento8 páginasStem Whitepaper Developing Academic VocabKainat BatoolAún no hay calificaciones

- Checklist For Portfolio Evidence (426 & 501) (Final)Documento1 páginaChecklist For Portfolio Evidence (426 & 501) (Final)undan.uk3234Aún no hay calificaciones

- WendyDocumento5 páginasWendyNiranjan NotaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Rup VolvoDocumento22 páginasRup Volvoisabelita55100% (1)

- English Balbharati STD 1 PDFDocumento86 páginasEnglish Balbharati STD 1 PDFSwapnil C100% (1)

- School-Based Telemedicine For AsthmaDocumento9 páginasSchool-Based Telemedicine For AsthmaJesslynBernadetteAún no hay calificaciones

- The Impact of Integrating Social Media in Students Academic Performance During Distance LearningDocumento22 páginasThe Impact of Integrating Social Media in Students Academic Performance During Distance LearningGoddessOfBeauty AphroditeAún no hay calificaciones

- Civil Engineering Colleges in PuneDocumento6 páginasCivil Engineering Colleges in PuneMIT AOE PuneAún no hay calificaciones

- MAMBRASAR, S.PDDocumento2 páginasMAMBRASAR, S.PDAis MAún no hay calificaciones

- Jennifer Valencia Disciplinary Literacy PaperDocumento8 páginasJennifer Valencia Disciplinary Literacy Paperapi-487420741Aún no hay calificaciones

- 07 - FIM - Financial Inclusion and MicrofinanceDocumento3 páginas07 - FIM - Financial Inclusion and MicrofinanceNachikethan.mAún no hay calificaciones

- REVIEW of Reza Zia-Ebrahimi's "The Emergence of Iranian Nationalism: Race and The Politics of Dislocation"Documento5 páginasREVIEW of Reza Zia-Ebrahimi's "The Emergence of Iranian Nationalism: Race and The Politics of Dislocation"Wahid AzalAún no hay calificaciones

- Assignment 2Documento2 páginasAssignment 2CJ IsmilAún no hay calificaciones

- English Vi October 29Documento3 páginasEnglish Vi October 29Catherine RenanteAún no hay calificaciones

- Laser Coaching: A Condensed 360 Coaching Experience To Increase Your Leaders' Confidence and ImpactDocumento3 páginasLaser Coaching: A Condensed 360 Coaching Experience To Increase Your Leaders' Confidence and ImpactPrune NivabeAún no hay calificaciones

- Approach Method TechniqueDocumento2 páginasApproach Method TechniquenancyAún no hay calificaciones

- Samuel Christian College: 8-Emerald Ms. Merijel A. Cudia Mr. Rjhay V. Capatoy Health 8Documento7 páginasSamuel Christian College: 8-Emerald Ms. Merijel A. Cudia Mr. Rjhay V. Capatoy Health 8Jetlee EstacionAún no hay calificaciones

- Suchita Srivastava & Anr Vs Chandigarh Administration On 28 August 2009Documento11 páginasSuchita Srivastava & Anr Vs Chandigarh Administration On 28 August 2009Disability Rights AllianceAún no hay calificaciones

- Child Development in UAEDocumento6 páginasChild Development in UAEkelvin fabichichiAún no hay calificaciones

- Exposición A La Pornografía e Intimidad en Las RelacionesDocumento13 páginasExposición A La Pornografía e Intimidad en Las RelacionespsychforallAún no hay calificaciones

- 3 20 Usmeno I Pismeno IzrazavanjeDocumento5 páginas3 20 Usmeno I Pismeno Izrazavanjeoptionality458Aún no hay calificaciones

- Osborne 2007 Linking Stereotype Threat and AnxietyDocumento21 páginasOsborne 2007 Linking Stereotype Threat and Anxietystefa BaccarelliAún no hay calificaciones

- The Public Stigma of Birth Mothers of Children With FASDDocumento8 páginasThe Public Stigma of Birth Mothers of Children With FASDfasdunitedAún no hay calificaciones

- Sumulong College of Arts and Sciences: High School DepartmentDocumento5 páginasSumulong College of Arts and Sciences: High School DepartmentShaira RebellonAún no hay calificaciones