Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Ccam N Bps Management PDF

Cargado por

Ethan AmalTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Ccam N Bps Management PDF

Cargado por

Ethan AmalCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

DIAGNOSIS AND mANAGemeNt UPDAte

Congenital Cystic Lesions of the

Lung: Congenital Cystic Adenomatoid

Malformation and Bronchopulmonary

Sequestration

Anna K. Sfakianaki, MD, MPH, Joshua A. Copel, MD

Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, & Reproductive Sciences,

Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

Congenital cystic lesions of the lung in fetuses are rare. The most common malforma-

tions of the lower respiratory tract are congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation

and bronchopulmonary sequestration. With the increased use of obstetric ultrasound,

cystic lung lesions are detected more often antenatally, which allows for proper

planning of peripartum and neonatal management. This article discusses a range of

diagnostic and management options.

[Rev Obstet Gynecol.2012;5(2):85-93doi:10.3909/riog0183a]

2012 MedReviews , LLC.

Key words

Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation Bronchopulmonary sequestration Congenital

pulmonary airway malformation Pulmonary hypoplasia

C

ongenital cystic lesions of the lung are rare. and bronchopulmonary sequestration (BPS).

The most common malformations of the With the increased use of obstetric ultrasound,

lower respiratory tract are congenital cystic cystic lung lesions are detected more often, which

adenomatoid malformation (CCAM), also known allows for proper planning of peripartum and

as congenital pulmonary airway malformation, neonatal management.

Vol. 5 No. 2 2012 Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology 85

40041700003_RIOG0183A.INDD 85 6/29/12 5:38 PM

Congenital Cystic Lesions of the Lung: CCAM and BPS continued

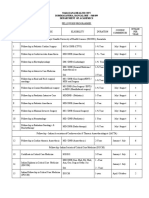

TABLe 1

Differences Between CCAM and BPS

CCAM BPS

Intralobar Extralobar

Incidence 1/11,000-1/35,000 Rare

Vascular supply Pulmonary Systemic: lower thoracic or Systemic: thoracic aorta

upper abdominal aorta

Laterality 80%-95% unilateral, either lobe 60% left sided 90% left sided

Sex Male . Female Male 5 Female Male . Female

Tracheobronchial Present, constricted/anomalous None None

communication

Associated anomalies Rare except for Type 2 (60%) 17% 40%

BPS, bronchopulmonary sequestration; CCAM, congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation.

Incidence and of tissues, airway obstruction, another (Table 1). Classification

Pathogenesis and dysplasia and metaplasia of schemes for CCAM have evolved,

The reported incidence of CCAM normal tissues.7 In most cases, it and there are currently five main

ranges from 1 in 11,000 to 1 in seems that the insult occurs dur- types, which differ based on the

35,000 live births, with a higher ing the pseudoglandular phase of embryologic level of origin and the

incidence in the midtrimester due lung development, which spans 7 histologic features (Figure 1).8,9

to spontaneous resolution.1,2 BPS is to 17 weeks of gestation.

Type 0

Type 0 CCAM is the rarest form

CCAM is a hamartomatous lesion containing tissue from different pul-

monary origins. BPS is made of extraneous and nonfunctioning lung and arises from the trachea or bron-

tissue that has separated itself from the normal pulmonary structure. chus. The presentation is severe and

usually lethal.10 Cysts are small.

even more rare, with no published

population incidence. CCAM Key Diagnostic Features Type 1

and BPS represent abnormalities There is significant overlap in the Type 1 CCAM is the most common

that occur during the branching findings and course of CCAM and form, representing 50% to 70% of

and proliferation of the bronchial BPS; however, a number of key fea- cases, and it arises from the distal

structures. CCAM is a hamarto- tures distinguish them from one bronchus or proximal bronchiole.

matous lesion containing tissue Figure 1. Congenital cystic adenomatoid

from different pulmonary origins. malformation classification based on pre-

BPS is made of extraneous and sumed site of development of the malfor-

mation. 0 5 tracheobronchial, 1 5 bronchial/

nonfunctioning lung tissue that bronchiolar, 2 5 bronchiolar, 3 5 bronchiolar/

has separated itself from the nor- alveolar, 4 5 distal acinar. Stocker JT, Fetal

Pediatr Pathol. 2009;28:155-184, copyright

mal pulmonary structure. Both 2009, Informa Healthcare. Reproduced

lesions have malignant potential.3 with permission from Informa Healthcare.9

In addition, hybrid lesions exist

that contain features of both.4,5

Thus, although the pathogenesis

of these lesions is poorly under-

stood, they may have a common

origin.6 Theories of their pathogen-

esis include abnormal proliferation

86 Vol. 5 No. 2 2012 Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology

40041700003_RIOG0183A.INDD 86 6/29/12 5:16 PM

Congenital Cystic Lesions of the Lung: CCAM and BPS

Figure 2. Case 1. Type 2 congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM). A, Sagittal image of a fetus at 24 weeks with Type 2 CCAM located

in the posterior chest (arrows). B, Transverse image with measurements showing the inferior extent of the lesion. The mass is multicystic and

located inferior and posterior to the heart. Arrowhead indicates the stomach.

There are usually a small number Figure 3. Computed tomography scan

of the neonate in Case 1, performed

of large echolucent cysts, measur- on day of life 1. There is a 0.9 3 0.9 cm

ing 3 to 10 cm.10 A single dominant mass with several cysts within the medial

segment of the right lower lobe. No

cyst may also be seen. Cyst walls are systemic vessels can be seen supplying

thin and are lined by ciliated pseu- the mass. Findings are consistent with a

Type 2 congenital cystic adenomatoid

dostratified epithelium, although malformation.

other cell types such as cartilage

may be found between the cysts.

Because these CCAMs may be large,

they may have significant mass

effect, which can lead to hydrops.

Type 2

Type 2 CCAMs account for 15% or columnar epithelium, and ele- which include most organ systems

to 30% of cases and arise from ments of bronchioles or alveoli may (Figures 2-7).10

terminal bronchioles. They are be seen. Frequently the cysts are

composed of smaller cysts, mea- more evenly spaced than in Type1 Type 3

suring 0.5 to 2 cm, as well as solid CCAMs. Type 2 CCAMs have the Type 3 CCAMs account for 5% to

areas that may be difficult to dis- highest incidence of associated 10% of cases and are thought to

tinguish from surrounding tissue. anomalies, up to 60%, and prog- arise from acinar-like tissue. Type3

These are lined by ciliated cuboidal nosis depends on these findings, CCAMs are composed of cysts that

Figure 4. Gross image of the Type 2 congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation seen in Figure 1. The ascites resolved by 24 weeks and the fetus

was stable until delivery. The neonate underwent right lower lobe lobectomy on day of life 2 due to persistent mediastinal shift.

Vol. 5 No. 2 2012 Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology 87

40041700003_RIOG0183a.INDD 87 6/26/12 5:46 PM

Congenital Cystic Lesions of the Lung: CCAM and BPS continued

Figure 5. Case 2. A, Transverse image of a fetus at 22 weeks with Type 2 congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM). The heart has been displaced into the

right thorax due to the large CCAM. Note the two cysts within the echogenic mass of the CCAM. B, Sagittal image of the fetus demonstrating ascites. Note the liver

with surrounding fluid. The ascites resolved 3 weeks later and the mass was resected on day of life 2 due to persistent mediastinal shift.

Figure 6. Computed tomography scan

of the neonate in Case 2 on day of

life 1. Findings are compatible with

cystic adenomatoid malformation of

the left upper lobe with associated

marked hyperinflation causing right-

ward mediastinal shift and deviation

of the descending thoracic aorta. Note

less marked involvement of the basilar

segments of the left lower lobe. The

patient underwent left upper lobe

lobectomy at 4 months of life (see

Figure 7).

Figure 7. Gross and histologic specimens of the patient in Case 2; the patient underwent left upper lobe lobectomy at 4 months of life. Histology

shows several small evenly spaced cystic structures of relatively uniform size are present in the area illustrated. The cysts are lined by ciliated

cuboidal to columnar epithelium that overlies a fine fibromuscular layer, barely visible at this magnification. Image courtesy of A. Brian West,

MD, FRCPath, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT.

88 Vol. 5 No. 2 2012 Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology

40041700003_RIOG0183a.INDD 88 6/26/12 5:46 PM

Congenital Cystic Lesions of the Lung: CCAM and BPS

macrocystic lesions and as such On ultrasound, Types 1 and 2

have been associated with poorer CCAM are usually easier to dis-

prognosis.12 Types 1, 2, and 4 tinguish from BPS because of

CCAMs are classified as macro- their more macrocystic appear-

cystic or both macrocystic and ance. Type 3 CCAM and BPS have

microcystic. Type 3 CCAMs are similar sonographic appearances

microcystic. and are therefore classically distin-

BPS can be either intralobar guished by their location (ie, BPS

(ILS) or extralobar (ELS) depend- is intra-abdominal) and through

ing on whether the mass is within their vascular supply using Doppler

Figure 8. Case 3. Sagittal image of a fetus at or outside of a normal lung lobe.13 interrogation. CCAM are supplied

20 weeks with Type 3 congenital cystic adeno-

matoid malformation demonstrating its position

posterior and to the left of the heart. The heart is BPS can be either intralobar or extralobar depending on whether

displaced to the right.

the mass is within or outside of a normal lung lobe.

ILS are contained within the lung and drained through the pulmo-

and do not have their own pleura, nary circulation, whereas BPS has

whereas EPS are completely cov- arterial flow directly from the

ered with pleura. Although this aorta. However, as mentioned pre-

distinction cannot usually be viously, CCAMs supplied through

made on ultrasound, ELS is more the systemic circulation have been

common in the fetus and may reported,4 and ultimately histologic

even be extrathoracic, with 10% diagnosis cannot be made ante-

of lesions noted below the dia- natally.5 In addition, the normal

phragm, usually on the left side.14 fetal lung becomes more echogenic

Figure 9. Case 3. Severe Type 3 congenital cystic Both ILS and ELS appear as solid, through gestation, and therefore

adenomatoid malformation. The lesion has

become large enough to compress the cardiac well-circumscribed and echogenic these lesions may become more dif-

anatomy. This fetus is at risk for hydrops. masses on ultrasound, similar to ficult to visualize over time.

Type 3 CCAM (Figures 10-12). Depending on the size of the

The major differences between lesion, other possible findings

are so small the mass appears to ILS and ELS are summarized in include polyhydramnios, medi-

be solid and highly echogenic on Table 1. astinal shift, pleural effusions,

ultrasound (Figures 8 and 9). The

tissue is acinar and shows adeno-

matoid elements consistent with

distal airway. These masses may be

large and may distort the thoracic

contents; prognosis depends on the

extent to which they do so.

Type 4

Type 4 CCAMs account for 5% to

15% of cases. These CCAMs con-

tain large cysts that may be as large

as 10 cm and have been associated

with malignancy, specifically pleu-

ropulmonary blastoma.11 They are

alveolar in origin.

Antenatally, CCAMs have been

classified as microcystic (, 5 mm)

versus macrocystic (. 5 mm).

Figure 10. Case 4. Axial image of a fetus with bronchopulmonary sequestration demonstrating the four-

Microcystic lesions are fre- chamber view and the proximity to the descending aorta. The fetus never developed hydrops and the mass

quently significantly larger than was resected electively at age 3 months.

Vol. 5 No. 2 2012 Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology 89

40041700003_RIOG0183a.INDD 89 6/26/12 5:46 PM

Congenital Cystic Lesions of the Lung: CCAM and BPS continued

Figure 11. Computed tomography scan of Teratoma tend to be more vascular

the neonate in Case 4 on day of life 2.

There is a solid soft tissue density within and may create more ultrasound

the left lower lobe measuring approxi- shadowing.

mately 3 cm 3 2 cm. A small vessel arising

from the descending aorta is seen sup- A bronchogenic cyst is usually

plying this solid mass (arrows); findings isolated and originates from the

are consistent with sequestration. The

baby underwent resection of the mass at

upper airway, with which a direct

3 months of age. connection can sometimes be visu-

alized. However, if the cyst is more

removed from the airway, differ-

entiating it from a macrocystic

CCAM may be difficult.

ELS and ILS cannot usually be

distinguished, but a pleural effu-

sion would suggest the former.

Figure 12. Histology slide from the resec- Intra-abdominal ELS are usually

tion in Case 4. Dilated airways in this

part of the specimen are filled with pale-

located on the left and must be dis-

staining mucin secondary to obstruction. tinguished from adrenal and renal

Image courtesy of A. Brian West, MD, lesions such as neuroblastoma and

FRCPath, Yale School of Medicine, New

Haven, CT. mesoblastic nephroma. Another

diagnosis to consider is enteric

duplication cysts, which are also

more common but have a more cys-

tic appearance.

MRI may be useful in distin-

guishing these lesions; however,

the technique has not been studied

extensively.16,17

and hydrops. Large lesions may connections cannot be visualized.

compress residual tissue, thus Other diagnoses such as congeni- Associated Anomalies

increasing the risk of pulmonary tal diaphragmatic hernia (CDH), CCAMs are usually isolated and

hypoplasia, which cannotat this congenital lobar emphysema, sporadic, although they have been

timebe predicted by antenatal and bronchogenic cyst should be associated with other anomalies

imaging. considered. (most commonly cardiac and renal)

In CDH, the lung mass is intes- in 15% to 20% of cases.18 An impor-

tine, which may appear cystic and tant exception is Type 2 CCAM, in

Differential Diagnosis thus mimic CCAM and/or BPS. which a majority of cases (~ 60%)

The differential diagnosis of a The presence of peristalsis sug- are associated with other findings,

thoracic mass is broad. Specific gests CDH. The stomach may also including cardiac anomalies, renal

lesions and clues to refine their be intrathoracic, in which case it agenesis/dysgenesis, gastrointesti-

differential diagnoses are dis- may fill and empty. Absence of an nal atresia, and skeletal anomalies.10

cussed next. intra-abdominal stomach bubble Specific cardiac anomalies include

Differentiating Type 3 CCAM also suggests CDH. Depending on truncus arteriosus and tetralogy of

from intrathoracic BPS may be the size of the CDH, the herniated Fallot.

challenging. Both Type 3 CCAM organs may move from intratho- BPS is more commonly associ-

and BPS are solid-appearing echo- racic to intra-abdominal. CDH ated with other anomalies than

genic masses with well-defined and both CCAM and BPS have CCAM. Abnormalities of the chest

borders. They are primarily dis- also been reported in the same wall, lung, diaphragm, spine, intes-

tinguished through their blood patient, further complicating the tine, and heart have been reported

supply, with BPS having direct sys- diagnosis.15 in 40% to 50% of ELS cases.19 ELS

temic vascularization off the aorta. Mediastinal masses such as cys- and Type 2 CCAM have been

However, differentiation may be tic hygroma and teratoma must reported to occur together in 50%

difficult, especially if the vascular be considered in the differential. of ELS cases.20 The incidence of

90 Vol. 5 No. 2 2012 Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology

40041700003_RIOG0183a.INDD 90 6/26/12 5:46 PM

Congenital Cystic Lesions of the Lung: CCAM and BPS

associated anomalies is much less with BPS, unless pleural effusions improved with drainage or resec-

with ILS, ranging around 15%.21 or hydrops develops. In that case, tion in the setting of hydrops, but

Connections to the gastrointestinal antenatal intervention is recom- not in fetuses without hydrops.26

system (stomach, esophagus) are mended because prognosis is poor. Both thoracocentesis and thora-

most common and may affect man- Possible interventions include coamniotic shunting allow for

agement due to risk of infection.19 thoracocentesis, thoracoamniotic decompression of the cyst and/or

There is no known association shunt, and laser ablation or injec- the thoracic cavity with relief of

with chromosome abnormalities in tion of a sclerosing agent into the both cardiac and pulmonary com-

either CCAM or BPS.19,22 feeding artery. Experience with pression. However, cysts may accu-

these therapies is limited to case mulate fluid again rapidly and

reports and case series. A system- shunts may become dislodged, so

Obstetrical Management atic review that summarized this repeat placement is often necessary.

Suspicion of a lung mass should experience reported prenatal sur- The more definitive option is open

trigger referral to a center special- vival of 100% in published cases; fetal surgery, which is associated

izing in prenatal diagnosis. Initial neonatal survival was 92%.23 with both fetal and maternal com-

evaluation should include detailed Hydrops develops more com- plications. Therefore, open surgery

ultrasound to assess for associ- monly in CCAM than in BPS, with is reserved for cases with the poor-

ated anomalies. Fetal echocardio- reported rates up to 40%.24 Hydrops est prognosis and to those prior to

gram is important to fully assess is more common in microcystic 32 to 34 weeks of gestation.25 After

cardiac anatomy and function. CCAM, CCAM with a dominant that point, the fetus should be

delivered and treated accordingly.

Laser ablation and injection of scle-

Fetal echocardiogram is important to fully assess cardiac anatomy

and function.

rosing agents have also been

described in the treatment of

Amniocentesis for karyotype is cyst, and CCAM with a higher vol- microcystic CCAM, in which cysts

not absolutely indicated, but is use- ume as measured by the CCAM are too small for decompression;

ful especially if it will help guide volume ratio.12,24 However, none of however, these reports are limited

treatment decisions. Consultation these markers is sensitive enough to cases.23

should be arranged with the neo- to allow accurate prediction of Small series suggest that there

natology and pediatric surgery hydrops, and even CCAMs in the may be a benefit to steroid ther-

services in order to fully counsel presence of hydrops have been apy in the setting of hydrops

patients on possible outcomes. reported to resolve; therefore, close CCAM and this should be con-

Depending on gestational age, follow-up of all fetuses with CCAM sidered if other fetal interventions

termination of pregnancy should is suggested. Hydrops is unlikely to are not available, or perhaps as a

be discussed, especially in the develop after 28 weeks, given the first-line agent prior to open sur-

setting of associated anomalies, natural course of CCAM growth to gery.23,27 Cesarean delivery is the

abnormal karyotype, or early-onset plateau at 25 weeks. Mortality in usual obstetric indication for both

circulatory compromise. Patients the setting of hydrops is high, and lesions.

whose fetuses have small lesions, or

those fetuses in whom lesions seem Mortality in the setting of hydrops is high, and fetal intervention for

to regress, may likely deliver in CCAM with hydrops is recommended depending on gestational age.

their usual facility. Care should be

transferred to a facility with expert fetal intervention for CCAM with Antenatal Monitoring

neonatal services and a range of hydrops is recommended depend- Serial ultrasound monitoring of

pediatric surgery options in cases ing on gestational age.3 Similar to congenital cystic lung lesions has

of fetuses with large lesions, or BPS, options include thoracocente- demonstrated that a significant

those with evidence of fetal com- sis, thoracoamniotic shunts, and proportion of these lesions decrease

promise. In these cases, significant open fetal surgery with CCAM in size and may regress spontane-

respiratory support and even extra- resection.25 Data regarding the ously; therefore, antenatal treat-

corporeal membrane oxygenation effectiveness of these procedures ment is not usually required.18 It

may be required. are limited to observational stud- appears that the natural course of

Intervention during pregnancy ies. A systematic review of these CCAM is growth until 25 weeks of

is rarely required for the fetus studies found that survival was gestation, after which it may plateau

Vol. 5 No. 2 2012 Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology 91

40041700003_RIOG0183a.INDD 91 6/29/12 12:14 PM

Congenital Cystic Lesions of the Lung: CCAM and BPS continued

in size or even regress.24 Given 3.2% of patients became symptom- Survival to delivery is reported

that the fetus continues to grow, it atic in the period of follow-up, and in . 95% of cases of CCAM and

appears that the CCAM is resolv- this occurred within 10 months in BPS.23,29 In fetuses who do not

ing. However, although the lesions the majority of cases. Expectant develop hydrops, postnatal sur-

may seem to disappear antenatally, management could be considered vival has been reported at nearly

a significant proportion persist on but if surgery is elected it should be 100%.23,25 In fetuses with hydrops

postnatal imaging and therefore performed in the first 10 months of who undergo prenatal intervention,

follow-up is suggested regardless of life. Data were not analyzed sepa- survival has been reported at a mean

the prenatal ultrasound course.28 rately for CCAM and BPS. of 80%, with rates up to 100% for

We monitor patients at 1- to Another argument for resection those treated with thoracocentesis.23

3-week intervals until stability of of all lesions, regardless of symp- Neonatal survival was 69%. Only

the lesion has been established, and tomatology, is the discordance in two small studies have reported on

then typically monthly thereafter. radiologic and histologic diagnosis, long-term neurodevelopmental fol-

Antenatal testing with nonstress which may occur in a significant low-up after fetal surgery for micro-

test or biophysical profile has not number of patients.30 Finally, early cystic CCAM, and outcome was

been studied prospectively. If there resection may allow for compen- favorable in those 10 patients.25,31

are signs of hydrops, more intensive satory lung development in the Type 0 CCAM is considered

monitoring, possibly in the inpa- remaining tissue.18 lethal. Resection of Type 1 CCAM

tient setting, is indicated. Surgical management of CCAM is considered to be curative and out-

and BPS involves lobectomy comes are excellent.18 Outcomes for

Neonatal Management or nonanatomical segmentectomy. Type 2 CCAM depend largely on

Treatment of CCAM and BPS Lobectomy is suggested for CCAM the presence of associated anoma-

depends on location and neonatal and ILS because of risks of incom- lies, as just reviewed. The risk of

status. In the case of respiratory plete resection, which occurs in 15% pulmonary hypoplasia is highest

compromise, resection is indicated of cases.29 In both ILS and ELS, the with Type 3 CCAM, given its ten-

and is curative. Minimally invasive vascular supply may be difficult to dency for growth and mass effect.

Pulmonary hypoplasia cannot, at

In the case of respiratory compromise, resection is indicated and is this time, be predicted antenatally.

curative. Similar to Type 3 CCAM, the

prognosis for BPS depends on the

surgery is quickly becoming the identify and bleeding is a risk. ILS degree of pulmonary hypoplasia.

standard of care for these patients. has been associated with chronic Intra-abdominal ELS seems to have

At least half of patients diag- infections due to connections improved outcomes over ILS

nosed with CCAM antenatally are with the gastrointestinal tract and because of decreased risk for pul-

asymptomatic at birth. Because many authors recommend resec- monary hypoplasia.

of the risk of infection and of tion regardless of the presence or

malignant transformation, most absence of symptoms.18 ELS has References

authors recommend resection of not been associated with infection 1. Laberge JM, Flageole H, Pugash D, et al. Outcome of

the prenatally diagnosed congenital cystic adenoma-

all antenatally diagnosed CCAMs, or malignant transformation and toid lung malformation: a Canadian experience. Fetal

although often the surgery can be therefore many authors recommend Diagn Ther. 2001;16:178-186.

2. Gornall AS, Budd JL, Draper ES, et al. Congenital cys-

deferred until several months after expectant management with serial tic adenomatoid malformation: accuracy of prenatal

birth. All removed tissue should be imaging in asymptomatic patients. diagnosis, prevalence and outcome in a general popu-

lation. Prenat Diagn. 2003;23:997-1002.

examined histologically. In stable 3. Bianchi DW, Crombleholme TM, DAlton ME, Malone

patients, the timing of elective sur- FE, eds. Fetology. Diagnosis and Management of the Fetal

gery is controversial. A systematic Prognosis 4.

Patient. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2010.

Cass DL, Crombleholme TM, Howell LJ, et al. Cystic

review and meta-analysis of cases Prognosis of antenatally detected lung lesions with systemic arterial blood supply: a

hybrid of congenital cystic adenomatoid malforma-

of congenital cystic lung lesions cystic lung lesions depends mainly tion and bronchopulmonary sequestration. J Pediatr

was performed in order to answer on specific histology of the lesion, Surg. 1997;32:986-990.

5. Davenport M, Warne SA, Cacciaguerra S, et al.

this question of timing.29 A total of associated anomalies, presence or Current outcome of antenally diagnosed cystic lung

41 reports including 1070 patients absence of hydrops or other signs of disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:549-556.

6. Shanti CM, Klein MD. Cystic lung disease. Semin

were studied and it was found that cardiovascular compromise, and risk Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:2-8.

elective surgery was associated of pulmonary hypoplasia based on 7. Langston C. New concepts in the pathology of con-

genital lung malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg.

with improved outcomes. Only degree of residual lung compression. 2003;12:17-37.

92 Vol. 5 No. 2 2012 Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology

40041700003_RIOG0183a.INDD 92 6/26/12 5:46 PM

Congenital Cystic Lesions of the Lung: CCAM and BPS

8. Stocker JT, Madewell JE, Drake RM. Congenital cystic 16. Hubbard AM, Adzick NS, Crombleholme TM, 24. Crombleholme TM, Coleman B, Hedrick H, et al.

adenomatoid malformation of the lung. Classification et al. Congenital chest lesions: diagnosis and char- Cystic adenomatoid malformation volume ratio pre-

and morphologic spectrum. Hum Pathol. 1977;8: acterization with prenatal MR imaging. Radiology. dicts outcome in prenatally diagnosed cystic adeno-

155-171. 1999;212:43-48. matoid malformation of the lung. J Pediatr Surg.

9. Stocker JT. Cystic lung disease in infants and children. 17. Matsuoka S, Takeuchi K, Yamanaka Y, et al. 2002;37:331-338.

Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2009;28:155-184. Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and 25. Adzick NS, Harrison MR, Crombleholme TM, et al.

10. Priest JR, Williams GM, Hill DA, et al. Pulmonary ultrasonography in the prenatal diagnosis of con- Fetal lung lesions: management and outcome. Am J

cysts in early childhood and the risk of malignancy. genital thoracic abnormalities. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2003; Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:884-889.

Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44:14-30. 18:447-453. 26. Knox EM, Kilby MD, Martin WL, Khan KS. In-utero

11. MacSweeney F, Papagiannopoulos K, Goldstraw P, 18. Laje P, Liechty KW. Postnatal management and out- pulmonary drainage in the management of primary

et al. An assessment of the expanded classification come of prenatally diagnosed lung lesions. Prenat hydrothorax and congenital cystic lung lesion: a system-

of congenital cystic adenomatoid malformations and Diagn. 2008;28:612-618. atic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;28:726-734.

their relationship to malignant transformation. Am J 19. Azizkhan RG, Crombleholme TM. Congenital cystic 27. Tsao K, Hawgood S, Vu L, et al. Resolution of hydrops

Surg Pathol 2003;27:1139-1146. lung disease: contemporary antenatal and postnatal fetalis in congenital cystic adenomatoid malforma-

12. Adzick NS, Harrison MR, Glick PL, et al. Fetal cystic management. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24:643-657. tion after prenatal steroid therapy. J Pediatr Surg.

adenomatoid malformation: prenatal diagnosis and 20. Conran RM, Stocker JT. Extralobar sequestration with 2003;38:508-510.

natural history. J Pediatr Surg. 1985;20:483-488. frequently associated congenital cystic adenomatoid 28. Blau H, Barak A, Karmazyn B, et al. Postnatal man-

13. Berrocal T, Madrid C, Novo S, et al. Congenital malformation, type 2: report of 50 cases. Pediatr Dev agement of resolving fetal lung lesions. Pediatrics.

anomalies of the tracheobronchial tree, lung, and Pathol. 1999;2:454-463. 2002;109:105-108.

mediastinum: embryology, radiology, and pathology. 21. Van Raemdonck D, De Boeck K, Devlieger H, et al. 29. Stanton M, Njere I, Ade-Ajayi N, et al. Systematic

Radiographics. 2004;24:e17. Pulmonary sequestration: a comparison between review and meta-analysis of the postnatal manage-

14. Laje P, Martinez-Ferro M, Grisoni E, Dudgeon D. pediatric and adult patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. ment of congenital cystic lung lesions. JPediatr Surg.

Intraabdominal pulmonary sequestration. A case 2001;19:388-395. 2009;44:1027-1033.

series and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 22. Wilson RD, Hedrick HL, Liechty KW, et al. Cystic ade- 30. Tsai AY, Liechty KW, Hedrick HL, et al. Outcomes

2006;41:1309-1312. nomatoid malformation of the lung: review of genet- after postnatal resection of prenatally diagnosed

15. Ryan CA, Finer NN, Etches PC, et al. Congenital dia- ics, prenatal diagnosis, and in utero treatment. Am J asymptomatic cystic lung lesions. J Pediatr Surg.

phragmatic hernia: associated malformationscystic Med Genet A. 2006;140:151-155. 2008;43:513-517.

adenomatoid malformation, extralobular sequestra- 23. Witlox RS, Lopriore E, Oepkes D, Walther FJ. Neonatal 31. Cass DL, Olutoye OO, Cassady CI, et al. Prenatal diag-

tion, and laryngotracheoesophageal cleft: two case outcome after prenatal interventions for congenital nosis and outcome of fetal lung masses. J Pediatr Surg.

reports. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:883-885. lung lesions. Early Hum Dev. 2011;87:611-618. 2011;46:292-298.

MAIN PoINTs

Congenital cystic lesions of the lung are rare. The most common malformations of the lower respiratory tract

are congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM) and bronchopulmonary sequestration (BPS). Although

the pathogenesis of these lesions is poorly understood, they may have a common origin.

There is significant overlap in the findings and course of CCAM and BPS; however, a number of key features

distinguish them from one another. CCAMs are currently classified into one of five main types.

Serial ultrasound monitoring of congenital cystic lung lesions has demonstrated that a significant proportion

of these lesions decrease in size and may regress spontaneously; therefore, antenatal treatment is not usually

required.

Treatment of CCAM and BPS depends on location and neonatal status. In the case of respiratory compromise,

resection is indicated and is curative. Minimally invasive surgery is quickly becoming the standard of care for

these patients.

Vol. 5 No. 2 2012 Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology 93

40041700003_RIOG0183a.INDD 93 6/26/12 5:46 PM

También podría gustarte

- Lung Metabolism: Proteolysis and Antioproteolysis Biochemical Pharmacology Handling of Bioactive SubstancesDe EverandLung Metabolism: Proteolysis and Antioproteolysis Biochemical Pharmacology Handling of Bioactive SubstancesAlain JunodAún no hay calificaciones

- Ards 2Documento7 páginasArds 2LUCIBELLOT1Aún no hay calificaciones

- Central Line PlacementDocumento49 páginasCentral Line PlacementAndresPimentelAlvarezAún no hay calificaciones

- General AnaesthesiaDocumento53 páginasGeneral Anaesthesiapeter singal100% (2)

- Suppurative Lung Diseases: DR Faisal Moidunny Mammu Department of PaediatricsDocumento39 páginasSuppurative Lung Diseases: DR Faisal Moidunny Mammu Department of PaediatricsFaisal MoidunnyAún no hay calificaciones

- Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale PediaDocumento30 páginasCanadian Triage and Acuity Scale PediaPrince Jhessie L. AbellaAún no hay calificaciones

- Problem-based Approach to Gastroenterology and HepatologyDe EverandProblem-based Approach to Gastroenterology and HepatologyJohn N. PlevrisAún no hay calificaciones

- A Simple Guide to Hypovolemia, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsDe EverandA Simple Guide to Hypovolemia, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsAún no hay calificaciones

- Report EmpyemaDocumento32 páginasReport EmpyemaMylah CruzAún no hay calificaciones

- Abdominal Organ Transplantation: State of the ArtDe EverandAbdominal Organ Transplantation: State of the ArtNizam MamodeAún no hay calificaciones

- Atls Approach To Pediatric TraumaDocumento8 páginasAtls Approach To Pediatric TraumaMakoto KyogokuAún no hay calificaciones

- Diagnosis and Management of Shock: Dr. Nurkhalis, SPJP, FihaDocumento51 páginasDiagnosis and Management of Shock: Dr. Nurkhalis, SPJP, FihaHilmaAún no hay calificaciones

- Chest Tube and Water-Seal DrainageDocumento25 páginasChest Tube and Water-Seal DrainageGhadaAún no hay calificaciones

- Wound de His Cence FinalDocumento26 páginasWound de His Cence Finaldanil armandAún no hay calificaciones

- Diagnostic Thoracoscopy (VATS) in Lung CancerDocumento18 páginasDiagnostic Thoracoscopy (VATS) in Lung CancerlmdarlongAún no hay calificaciones

- DR Lily - Resp Distress in Newborn Infants PDFDocumento45 páginasDR Lily - Resp Distress in Newborn Infants PDFM Ilham MAún no hay calificaciones

- Laryngeal ObstructionDocumento59 páginasLaryngeal ObstructionpravinAún no hay calificaciones

- ICU Scoring Systems A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionDe EverandICU Scoring Systems A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionAún no hay calificaciones

- Endocrine Surgery: Butterworths International Medical Reviews: SurgeryDe EverandEndocrine Surgery: Butterworths International Medical Reviews: SurgeryI. D. A. JohnstonAún no hay calificaciones

- Update On The Management of LaryngospasmDocumento6 páginasUpdate On The Management of LaryngospasmGede Eka Putra NugrahaAún no hay calificaciones

- Vascular Responses to PathogensDe EverandVascular Responses to PathogensFelicity N.E. GavinsAún no hay calificaciones

- CHD2 - DR Shirley L ADocumento74 páginasCHD2 - DR Shirley L ARaihan Luthfi100% (1)

- Endotracheal Intubation: Oleh: Dr. Natalia Rasta M Pembimbing: Dr. Eko Widya, Sp. EMDocumento22 páginasEndotracheal Intubation: Oleh: Dr. Natalia Rasta M Pembimbing: Dr. Eko Widya, Sp. EMNatalia RastaAún no hay calificaciones

- ARDS LectureDocumento58 páginasARDS LecturedrjaikrishAún no hay calificaciones

- Midgut Volvulus 2018Documento2 páginasMidgut Volvulus 2018zzzAún no hay calificaciones

- Anesthesia For Tracheoesophageal Fistula RepairDocumento29 páginasAnesthesia For Tracheoesophageal Fistula RepairArop AkechAún no hay calificaciones

- Foreign Body AspirationDocumento3 páginasForeign Body AspirationAsiya ZaidiAún no hay calificaciones

- Interpretation Chest X RayDocumento127 páginasInterpretation Chest X RayVimal NishadAún no hay calificaciones

- FOM STUDY GUIDE 3rd Block 1Documento3 páginasFOM STUDY GUIDE 3rd Block 1Bernadine Cruz Par100% (1)

- FriS41700 PhlegmasiaCeruleaDolensisaLimbThreateningProblem BhendeDocumento54 páginasFriS41700 PhlegmasiaCeruleaDolensisaLimbThreateningProblem BhendeSuren VishvanathAún no hay calificaciones

- Foreign Bodies of The Ear and Nose - A Novel Technique of RemovalDocumento4 páginasForeign Bodies of The Ear and Nose - A Novel Technique of RemovalAnonymous lAfk9gNPAún no hay calificaciones

- 633815699386510632Documento123 páginas633815699386510632Muhammad FarisAún no hay calificaciones

- Bronchiectasis: Dr.K.M.LakshmanarajanDocumento238 páginasBronchiectasis: Dr.K.M.LakshmanarajanKM Lakshmana Rajan0% (1)

- MediastinumDocumento27 páginasMediastinumAndrei PanaAún no hay calificaciones

- DyspneaDocumento34 páginasDyspneaAlvin BrilianAún no hay calificaciones

- Pulmonary SequestrationDocumento15 páginasPulmonary SequestrationEmily EresumaAún no hay calificaciones

- Caseous Pneumonia: by Makarova Elena AlexandrovnaDocumento16 páginasCaseous Pneumonia: by Makarova Elena AlexandrovnaAMEER ALSAABRAWIAún no hay calificaciones

- 13Lec-Approach To Neonates With Suspected Congenital InfectionsDocumento56 páginas13Lec-Approach To Neonates With Suspected Congenital InfectionsMinerva Stanciu100% (1)

- Lung Development Biological and Clinical Perspectives: Biochemistry and PhysiologyDe EverandLung Development Biological and Clinical Perspectives: Biochemistry and PhysiologyPhilip FarrellAún no hay calificaciones

- AP WindowDocumento13 páginasAP WindowHugo GonzálezAún no hay calificaciones

- Dermatoscopy and Skin Cancer, updated edition: A handbook for hunters of skin cancer and melanomaDe EverandDermatoscopy and Skin Cancer, updated edition: A handbook for hunters of skin cancer and melanomaAún no hay calificaciones

- Gerry B. Acosta, MD, FPPS, FPCC: Pediatric CardiologistDocumento51 páginasGerry B. Acosta, MD, FPPS, FPCC: Pediatric CardiologistChristian Clyde N. ApigoAún no hay calificaciones

- Cor PulmonaleDocumento8 páginasCor PulmonaleAymen OmerAún no hay calificaciones

- 2013 ASA Guidelines Difficult AirwayDocumento20 páginas2013 ASA Guidelines Difficult AirwayStacey WoodsAún no hay calificaciones

- A Rare Case of Bochdalek Hernia in Adult: A Case ReportDocumento3 páginasA Rare Case of Bochdalek Hernia in Adult: A Case ReportAmbreen FatimaAún no hay calificaciones

- Air Leak SyndromesDocumento2 páginasAir Leak SyndromesIchalAzAún no hay calificaciones

- Bronchiectasis: By: Karunesh KumarDocumento21 páginasBronchiectasis: By: Karunesh KumarAnkan DeyAún no hay calificaciones

- Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis: Diagnostic and Therapeutic ChallengesDocumento51 páginasHypersensitivity Pneumonitis: Diagnostic and Therapeutic ChallengesskchhabraAún no hay calificaciones

- Guidelines On Management of Covid-19 Icu PatientDocumento32 páginasGuidelines On Management of Covid-19 Icu PatientBrainy LumineusAún no hay calificaciones

- Supraglottic Airway DevicesDocumento20 páginasSupraglottic Airway DevicesZac CamannAún no hay calificaciones

- Recovery Room Care: BY Rajeev KumarDocumento50 páginasRecovery Room Care: BY Rajeev Kumarramanrajesh83Aún no hay calificaciones

- Empyema 2Documento31 páginasEmpyema 2Michelle SalimAún no hay calificaciones

- European Consensus On The Management of RDSDocumento41 páginasEuropean Consensus On The Management of RDSDeddy Supriyadi100% (1)

- 766 - HPS - Emergency TKVDocumento82 páginas766 - HPS - Emergency TKVAdistyDWAún no hay calificaciones

- 8.the Atls ProtocolDocumento57 páginas8.the Atls ProtocolReuben DutiAún no hay calificaciones

- Infective Endocarditis: A Multidisciplinary ApproachDe EverandInfective Endocarditis: A Multidisciplinary ApproachArman KilicAún no hay calificaciones

- Parental Care and The Development of The Parent Offspring Conflict in Discus Fish (Symphysodon SPP.)Documento298 páginasParental Care and The Development of The Parent Offspring Conflict in Discus Fish (Symphysodon SPP.)Ethan AmalAún no hay calificaciones

- State of The Art Concepts in Aortic Valve Replacement: Please Join Us For The 90 MinutesDocumento1 páginaState of The Art Concepts in Aortic Valve Replacement: Please Join Us For The 90 MinutesEthan AmalAún no hay calificaciones

- Edwards iBAR Agenda 16thoct ThailandDocumento1 páginaEdwards iBAR Agenda 16thoct ThailandEthan AmalAún no hay calificaciones

- Narayana Health City Bommasandra, Bangalore - 560 099 Department of AcademicsDocumento2 páginasNarayana Health City Bommasandra, Bangalore - 560 099 Department of AcademicsEthan AmalAún no hay calificaciones

- Page Proof Instructions and Queries: Asian Cardiovascular & Thoracic Annals (AAN) 984097Documento6 páginasPage Proof Instructions and Queries: Asian Cardiovascular & Thoracic Annals (AAN) 984097Ethan AmalAún no hay calificaciones

- We Are Intechopen, The World'S Leading Publisher of Open Access Books Built by Scientists, For ScientistsDocumento35 páginasWe Are Intechopen, The World'S Leading Publisher of Open Access Books Built by Scientists, For ScientistsEthan AmalAún no hay calificaciones

- AA Issue-Article 9Documento11 páginasAA Issue-Article 9Ethan AmalAún no hay calificaciones

- Av Shunt Mabi XXDocumento33 páginasAv Shunt Mabi XXEthan AmalAún no hay calificaciones

- Safety of Temporary Pacemaker WiresDocumento20 páginasSafety of Temporary Pacemaker WiresEthan AmalAún no hay calificaciones

- A Last Resort?Documento942 páginasA Last Resort?SBS_NewsAún no hay calificaciones

- Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) Act: Implementing Rules and RegulationsDocumento44 páginasPantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) Act: Implementing Rules and RegulationsRyan ZaguirreAún no hay calificaciones

- Tolin Et Al. - 2010 - Course of Compulsive Hoarding and Its RelationshipDocumento11 páginasTolin Et Al. - 2010 - Course of Compulsive Hoarding and Its RelationshipQon100% (1)

- 13 Areas of Assessment Pedia DutyDocumento3 páginas13 Areas of Assessment Pedia DutyJoshua MendozaAún no hay calificaciones

- Assignment No 1 bt502 SeminarDocumento15 páginasAssignment No 1 bt502 SeminarMashal WakeelaAún no hay calificaciones

- Masker 1 2020 - Post Test (Edited)Documento12 páginasMasker 1 2020 - Post Test (Edited)Muhammad Ali MaulanaAún no hay calificaciones

- How Does Technology Lead To NeurosisDocumento3 páginasHow Does Technology Lead To Neurosisapi-347897735Aún no hay calificaciones

- Exercise Science Honours 2016Documento22 páginasExercise Science Honours 2016asdgffdAún no hay calificaciones

- Brad Blanton - Radical HonestyDocumento10 páginasBrad Blanton - Radical HonestyraduAún no hay calificaciones

- A Prospective Study On The Practice of Conversion of Antibiotics From IV To Oral Route and The Barriers Affecting ItDocumento3 páginasA Prospective Study On The Practice of Conversion of Antibiotics From IV To Oral Route and The Barriers Affecting ItInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyAún no hay calificaciones

- Presentation 2 Ptlls qrx0598Documento56 páginasPresentation 2 Ptlls qrx0598api-194946381100% (2)

- Difhtheria in ChildrenDocumento9 páginasDifhtheria in ChildrenFahmi IdrisAún no hay calificaciones

- Renfrew County Community Study Executive SummaryDocumento24 páginasRenfrew County Community Study Executive SummaryShawna BabcockAún no hay calificaciones

- Sehatvan Fellowship ProgramDocumento8 páginasSehatvan Fellowship ProgramShivam KumarAún no hay calificaciones

- ART THERAPY, Encyclopedia of Counseling. SAGE Publications. 7 Nov. 2008.Documento2 páginasART THERAPY, Encyclopedia of Counseling. SAGE Publications. 7 Nov. 2008.Amitranjan BasuAún no hay calificaciones

- Scheme of Work - Form 4: Week (1 - 3)Documento7 páginasScheme of Work - Form 4: Week (1 - 3)honeym694576Aún no hay calificaciones

- MAPEH 7 3rd Summative TestDocumento5 páginasMAPEH 7 3rd Summative TestFerlyn Bautista Pada100% (1)

- Emr408 A2 KL MarkedDocumento21 páginasEmr408 A2 KL Markedapi-547396509Aún no hay calificaciones

- Mitchell H. Katz-Evaluating Clinical and Public Health Interventions - A Practical Guide To Study Design and Statistics (2010)Documento176 páginasMitchell H. Katz-Evaluating Clinical and Public Health Interventions - A Practical Guide To Study Design and Statistics (2010)Lakshmi SethAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Study 2 2018Documento6 páginasCase Study 2 2018jigsawAún no hay calificaciones

- Anthropometric ResultDocumento2 páginasAnthropometric ResultNaveed AhmedAún no hay calificaciones

- Power of Plants 1Documento14 páginasPower of Plants 1api-399048965Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ngan 2018Documento9 páginasNgan 2018rafaelaqAún no hay calificaciones

- Ethical & Legal Issues in Canadian NursingDocumento950 páginasEthical & Legal Issues in Canadian NursingKarl Chelchowski100% (1)

- Puskesmas Wanggudu Raya: Dinas Kesehatan Kabupaten Konawe UtaraDocumento6 páginasPuskesmas Wanggudu Raya: Dinas Kesehatan Kabupaten Konawe UtaraicaAún no hay calificaciones

- Pengaruh Penambahan Kayu Manis TerhadapDocumento8 páginasPengaruh Penambahan Kayu Manis TerhadapIbnu SetyawanAún no hay calificaciones

- OT in The ICU Student PresentationDocumento37 páginasOT in The ICU Student PresentationMochammad Syarief HidayatAún no hay calificaciones

- GATS 2 FactSheetDocumento4 páginasGATS 2 FactSheetAsmi MohamedAún no hay calificaciones

- SITXWHS004 Assessment 1 - ProjectDocumento18 páginasSITXWHS004 Assessment 1 - Projectaarja stha100% (1)

- Essential Care of Newborn at BirthDocumento32 páginasEssential Care of Newborn at Birthastha singh100% (1)