Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Is Subtle Prejudice Really Prejudice - Pettigrew y Meertens

Cargado por

Manu Luna RodríguezDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Is Subtle Prejudice Really Prejudice - Pettigrew y Meertens

Cargado por

Manu Luna RodríguezCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

American Association for Public Opinion Research

Is Subtle Prejudice Really Prejudice?

Author(s): Roel W. Meertens and Thomas F. Pettigrew

Source: The Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 61, No. 1, Special Issue on Race (Spring, 1997), pp.

54-71

Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Association for Public Opinion Research

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2749511 .

Accessed: 10/09/2013 23:33

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Association for Public Opinion Research and Oxford University Press are collaborating with JSTOR

to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Public Opinion Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

IS SUBTLE PREJUDICE

REALLY PREJUDICE?

ROELW. MEERTENS

THOMASF. PETTIGREW

A more subtleform of out-groupprejudicehas emergedin recentyears.

Observershave describedit in similartermsin France,Germany,Great

Britain,the Netherlands,andNorthAmerica(Barker1984;Bergmannand

Erb 1986; Essed 1984; Freriks1990; McConahay1983; Pettigrew1989;

PettigrewandMeertens1995; Sears 1988). Blatantprejudiceis the tradi-

tional form; it is hot, close, and direct. In contrast,subtle prejudiceis

cool, distant,and indirect.Blatantprejudiceremains,but proponentsof

the subtle-prejudiceconcept maintainthat a conceptualdistinctionbe-

tween the two is useful.

Despite this convergence of observations,Snidermanand Tetlock

(1986a, 1986b; Snidermanet al. 1991; Tetlock 1994) questionwhether

subtle prejudiceis distinctfrom traditionalforms or even whetherit is

prejudiceat all. They ignore other conceptualizations(Pettigrew1989)

andfocus on Sears's(1988) symbolicracism.Theyregardit as "a flawed

idea" (Snidermanand Tetlock 1986b, p. 130). Centralto their host of

criticismsis theirconcernthatsymbolicracismis confoundedby political

conservatismand indicts conservativesas racists.

In response,this paperemploys extensive survey data from Western

Europeto test these criticalpoints andtheirimplications.We seek to an-

swer the basic question:Is subtleprejudicereally prejudice?We question

the SnidermanandTetlock(1986a, 1986b;Snidermanet al. 1991;Tetlock

1994) contentionsand work from a differentperspective.We posit the

following: (1) Subtleprejudiceagainstout-groupscan be measuredreli-

ably and separatelyfrom the more traditionalform of blatantprejudice.

ROEL W. MEERTENS is a professorof social psychology at the Universityof Amster-

dam, the Netherlands.THOMAS F. PETTIGREW is a researchprofessorof social psychol-

ogy at the Universityof California,SantaCruz.They wish to thanktheir colleagues in

the WorkingGroupon InternationalPerspectiveson Race and EthnicRelationsfor their

help and intellectualstimulation:JamesJackson,JeanneBen Brika,GerardLemaine,Ul-

richWagner,andAndreasZick.An earlierversionof this articlewas presentedto thejoint

meetingof the EuropeanAssociationof ExperimentalSocial Psychologyand the Society

for ExperimentalSocial Psychology,Washington,DC, October1995.

Public Opimon Quarterly Volume 61:54-71 ? 1997 by the American Association for Public Opinion Research

All nghts reserved. 0033-362X/97/6101-0003$02.50

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Is Subtle Prejudice Really Prejudice? 55

(2) Subtle prejudicewill relate closely to blatantprejudicebut is quite

distinctfrom political conservatism.(3) Moreover,we hold that subtle

prejudiceis an outgrowthof the establishmentof norms that proscribe

blatantexpressionsof prejudiceanddiscrimination.These normsarejust

developingin WesternEurope,as they are in NorthAmerica.Thus, the

blatant-subtledistinctionshouldprove especiallyuseful for those groups

and societies wheresuch an antiblatantnormhas takenroot-among the

well educated,the young, and the politicallyliberal.

Data and Measures

This researchexploits an unusuallyrich survey data source. These data

derive from 3,806 respondentsdrawn from seven nationalprobability

samples of four WesternEuropeannations.A variety of minoritiesare

the targetsof a wide rangeof prejudicemeasures.

The surveyswere conductedas partof the EuropeanCommunity'sEu-

robarometer30 surveyduringthe fall of 1988 in France,the Netherlands,

GreatBritain,andthen-WestGermany.Turkishimmigrantsservedas the

targetout-groupfor the entireWest Germansample.However,the study

drew two separatesamplesin each of the othercountries,so a varietyof

minoritiescouldserveas targetout-groups.In France,one samplefocused

on NorthAfricans,the otheron Asians(largelyVietnameseandCambodi-

ans). In the Netherlands,one focused on Surinamers,the otheron Turks.

In GreatBritain,one focusedon WestIndians,the otheron Asians(largely

Pakistanisand Indians).

We removedall minorityrespondents.This left a totalof 3,806 respon-

dents: 455 Frenchwere asked about North Africans;475 Frenchwere

askedaboutAsians;462 Dutchwere askedaboutSurinamers;476 Dutch

were askedaboutTurks;471 Britishwere askedaboutWest Indians;482

BritishwereaskedaboutAsians;and985 WestGermanswereaskedabout

Turks.Details of the samplingproceduresand the full schedule of the

Eurobarometer30 survey are availablein Reif and Melich (1991).

We used 10-itemLikertscales to measureBLATANTand SUBTLE

PREJUDICE(Pettigrewand Meertens 1995). The appendixshows the

scales in English.'StandardLikert-scalescoringwas used, with item re-

sponses scored 1, 2 (no 3), 4, and 5 as stronglydisagree,somewhatdis-

agree, somewhat agree, and strongly agree, respectively, dimension.

Higherscoresindicategreaterprejudice.Five items arereversalsin which

disagreementis scoredin theprejudiceddirection(items2-4 of the ANTI-

1. The Dutch,French,and Germanversionswere carefullyconstructedequivalentsusing

back-translation

methods.Copies of these scales are availablefrom Roel W. Meertens.

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

56 Roel W. Meertens and Thomas F. Pettigrew

INTIMACYsubscaleandthe two items of the AFFECTIVEPREJUDICE

subscale).2

From a pool of more than 50 separateitems, we chose 10 items to

measureeach type of prejudiceon the basis of our conceptualizationof

the two forms and exploratoryfactoranalyses.Ourconceptualizationof

BLATANTPREJUDICEfollows the standardsocial psychologicalprac-

tice of viewing it as involvingthreatcombinedwith bothformalandinti-

mate rejectionof the out-group.

Our conceptualizationof SUBTLEPREJUDICEfollows the findings

of both field and laboratoryexperimentson the subjectsummarizedby

Crosby,Bromley,and Saxe (1980) andGaertnerandDovidio (1986). In-

deed, experimentalfindingsdirectlyinspiredtwo of the subscalesof our

subtle measure. The cultural differences subscale exploits Rokeach's

(1960) workon belief dissimilarity.He foundthatthe assumptionof belief

and value differenceswith the out-groupimportantlyreflectedprejudice.

Our four items in the appendixmeasuringthe perceived CULTURAL

DI'FFRENCESwith the out-grouptap this dimension.

The AFFECTIVEPREJUDICEsubscale combinesfindingsfrom the

experimentalwork of Dijker (1987) and Dovidio, Mann, and Gaertner

(1989). Dijkerdemonstrated thatrespondentson the streetsof Amsterdam

could easily reporton their emotionalreactionsto out-groups.Dovidio,

Mann,and Gaertnershowedhow subtleprejudiceinvolves the denial of

negativeattributesof out-groups.Theirsubjectsrejectednegativestereo-

types of the out-groupbut readilyassignedmore positive stereotypesto

their in-group.Thus, the out-groupwas seen as not worse than the in-

group,butthe in-groupwas seen as betterthanthe out-group.The appen-

dix's two AFFECTIVEPREJUDICEitems ask respondentswhetherthey

have ever experiencedtwo positive emotions-admiration and sympa-

thy-toward the out-group.3

The commoningredientin all 10 of the SUBTLEPREJUDICEitems

is theircovertness-their ostensiblynonprejudicialcharacter.Indeed,as

Kovel (1970) argues,the prejudicialnatureof subtleprejudiceis typically

hiddenfromthosewho adoptthesebeliefs.Thiskey ingredientis precisely

what disturbscritics.Yet it is how this modem form of prejudiceevades

proscriptivenorms against blatantexpressionsof intergroupprejudice.

The subtle items are socially acceptableways to expressprejudice.Not

perceivedas revealingbias,subtleprejudiceslipsin underantiblatantprej-

udice norms. Thus, the critical distinctionbetween blatantand subtle

2. "Don't know" or missingresponseswereassignedthe individual'smeanon those scale

questionsanswered.This procedurewas used only for those answeringat least 4 of the

scale's 10 questions.Removingrespondentswith less thanfouranswersto the BLATANT

or SUBTLEscales resultedin samplelosses of less than 3 percent.

3. Consistentwith the findingsof Dovidio, Mann, and Gaertner(1989), two equivalent

items using negativeemotions-fear and irritation-did not scale.

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Is Subtle Prejudice Really Prejudice? 57

forms of prejudiceinvolves the differencebetween overt expressionof

norm-breakingviews againstminoritiesand the covertexpressionof so-

cially acceptableantiminorityviews.

We used as controlsseven variablesthathave, over years of research,

significantlypredictedprejudice(Allport 1954). The first controlis that

stressedby SnidermanandTetlock(1986a, 1986b;Snidermanet al. 1991;

Tetlock1994). Self-placementon a 10-pointscale rangingfromthe politi-

cal left to right assessed POLITICALCONSERVATISM.High scorers

are more conservative.To measureINTERGROUPFRIENDS,respon-

dentswere showna list: "Peopleof anothernationality,Peopleof another

race,Peopleof anotherreligion,Peoplewith anotherculture,"and "Peo-

ple belongingto anothersocial class." Interviewersaskedfor each item,

:'Are theremany such people" (scored3), "a few" (2), "or none" (or

no answer,scored 1) "thatcount amongyour friends?"

GROUPRELATIVEDEPRIVATION(GRD)is measuredby a single

item drawnfromVannemanand Pettigrew(1972): "Wouldyou say that

overthe last five yearspeoplelike yourselfin [France]havebeen econom-

ically a lot betteroff, betteroff, the same, worse off, or a lot worse off

thanmost [NorthAfricans]living here." High scorersfeel relativelyde-

privedin groupterms.

Two POLITICALINTERESTitems ask respondentshow interested

they are in politics generallyand in EuropeanCommunitypolitics spe-

cifically. High scorers report keen interest in both. To measure NA-

TIONALPRIDE,respondentsreportedhow proudtheywereto be British,

Dutch, French,or German.EDUCATIONreflects the respondent'sre-

portedage duringthe last year of schooling. We calculatedAGE from

reportedbirthdate.

Policy preferencesaboutimmigration,a key minorityissue in Europe,

providedependentvariablesfor ouranalyses.Definingimmigrantsas peo-

ple who reside in the nation but are citizens of neitherthe nation nor

the EuropeanCommunity,the surveysprovidea varietyof items about

immigration.One asks about the RIGHTS OF IMMIGRANTS:"we

should extend their rights" (scored 1), "restricttheir rights" (3), or

"leave things as they are" (2). Anotherasks whetherthe "presence"of

immigrantsis "a good thing" (1), "good to some extent" (2), "bad to

some extent" (3), "or a bad thingfor the futureof our country?"(4). A

thirdquestionaskswhethertherespondentthinks"thegovernmentshould

make every effort to improvethe social and economicpositionof [West

Indians] living in [Britain]-agree strongly" (1), "agree" (2), "dis-

agree" (4)" or "disagreestrongly" (5).

Anotherset of questionsconcernsPREFERREDMEANS "to improve

relationsbetweenthe [British]and [non-British]living here." Interview-

ers askedrespondentsif they thoughtit a "a good idea" or "a badidea"

to adopteach of nine differentactions.The mostcontroversialalternatives

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

58 Roel W. Meertens and Thomas F. Pettigrew

concernedmaking "naturalizationeasier," "learn[ing]the languageof

others,"and "know[ing]the culturalcustomsof others."Othersinvolved

nominalremediesthatrequireno effortby the respondentandwereuncon-

troversial- "promotethe teachingof tolerance... in schools," "encour-

age (intergroup)contact,""insurethatpeople ... treat[British]and[non-

British]equally,"and "expandinternationalexchangeprograms."Using

the entiresampleof 3,806 respondents,we formeda NOMINALREME-

DIES scale of these four items. High scorerssupportedall four modest

actions;the scale yields a marginalalphaof .70.

Again with the entiresample,we formeda six-itemmeasureof OPPO-

SITIONTO IMMIGRATION. The highestscorersbelieve thatimmigra-

tionis a badthing,immigrants'rightsshouldbe restricted,andthe govern-

mentshouldneithermakeeffortsto improvethe immigrants'positionnor

make naturalizationeasier.High scorersalso thinkit is "a bad idea" to

learnthe immigrants'languageandculturalcustoms.For the entiresam-

ple, the alphafor the OPPOSITIONTO IMMIGRATIONscale is .75.

A finalitem focuses on IMMIGRATION POLICY:"Thereare a num-

ber of policy options concerningthe presenceof [Turkish]immigrants

living here. In your opinion which is the one policy that the government

should adopt in the long run?" The respondent selected from six alterna-

tives listed on a card.4They rangedfromnot sending "backto theirown

country"any of the out-groupto sendingthemall back.The intermediate

choices varied who should be sent back: those "not born" here, those

"not contributing"to the economy,those "who have committedserious

criminaloffenses," or those "who have no immigrationdocuments."

Results

We pose eight empiricalquestionsrelevantto ourhypothesesconcerning

subtleprejudice:

1. Cansubtleprejudicebe effectivelymeasuredacrossnationalsamples

andfor a varietyof out-grouptargets?The scalingsuccess of the identical

BLATANTand SUBTLEPREJUDICEscales acrossseven samples,six

targetgroups,and four nationsoffers an affirmativeanswerto this ques-

tion. The median alphas for the BLATANT (.90) and SUBTLE (.77)

scales acrossthe seven samplesreach acceptablelevels.

The clarityof our factoranalyticresultsoffers additionalsupport.By

use of principle-components analyses, exploratoryfactor analysesyield

similarresultsacrossthe total sampleandthe seven nationalsamples.For

the BLATANTscale with the total sample,two primaryfactorsemerged

4. Since some of the alternatives are not mutually exclusive, more than one response was

allowed. The respondents averaged 1.6 responses each.

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Is Subtle Prejudice Really Prejudice? 59

Table 1. Correlations between Blatant and Subtle Prejudice

and Political Conservatism

Correlations

Partial

Blatant-

Subtlewith

Blatant- Conservatism Blatant- Subtle-

Subtle Controlled Conservatism Conservatism

Britishon Asians +.65 +.63 +.21 +.20

Britishon West

Indians +.69 +.65 +.25 +.24

Dutch on Surinamers +.53 +.50 +.26 +.19

Dutch on Turks +.48 +.45 +.25 +.16

Frenchon North

Africans +.70 +.63 +.32 +.33

Frenchon Asians +.65 +.61 +.24 +.22

Germanson Turks +.63 +.62 +.26 +.15

Total sample +.60 +.58 +.25 +.20

after varimax rotation: the four INTIMACY items (eigenvalue = 3.85)

and the six THREAT AND REJECTION items (eigenvalue = 1.09) listed

in the appendix. The same patternemerged in four of the national samples,

while one factor emerged in two samples and three in one sample. For

the SUBTLE scale with the total sample, three primary orthogonal factors

emerged after varimax rotation in the total sample: the four TRADI-

TIONAL VALUES items (eigenvalue = 1.69), the four CULTURAL

DIFFERENCES items (eigenvalue = 2.52), and the two AFFECTIVE

PREJUDICE items (eigenvalue = 1.13) of the appendix. This patternalso

emerged in all seven national samples.

2. How are the BLATANT and SUBTLE PREJUDICE measures re-

lated? Table 1 shows that the SUBTLE and BLATANT PREJUDICE

scales yield moderately high relationships in all samples-ranging from

+.48 to +.70. Controls for CONSERVATISM barely reduce this associa-

tion. The correlations between SUBTLE and BLATANT, with CONSER-

VATISM partialed out, still range between +.45 and +.65. This same

level emerges in American studies using diverse measures (+.49 by Ja-

cobson [1985], +.58 by McConahay [1982], and +.65 by McClendon

[1985]).

These results provide solid convergent validity for SUBTLE PREJU-

DICE. Yet, beyond measurement error, there is still room for differences

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

60 Roel W. Meertens and Thomas F. Pettigrew

Mean Effect Size (Pearson's r)

0.3

0.2

0. 1

0

EDUCATION FRIENDS AGE G.R.D. POL.INTERESTNAT.PRIDE

| Blatant Prejudice Subtle Prejudice

Figure 1. Predictorsof blatantand subtleprejudice.Source:Euro-

Barometer 30 survey, 1988.

between the two prejudicetypes to justify their delineation.But these

correlationscannot settle the issue. We must turnto their relationships

with both independentand dependentvariablesas well as confirmatory

factoranalyticevidence.

3. Do the samevariablespredictbothprejudicescales?Thereis a close

parallelbetweenthe predictorsof BLATANTandSUBTLEPREJUDICE

in figure 1. On both measures,those scoringhigh tend to be poorly edu-

cated,older,have only in-groupfriends,experiencegroupdeprivationrel-

ativeto the out-group,lack politicalinterest,andboastconsiderablepride

in theirnationality.

4. How do the prejudicescales relateto politicalconservatism?In table

1, conservativerespondentsscore significantlyhigheron both prejudice

scalesin all samples.Contraryto SnidermanandTetlock's(1986a, 1986b;

Snidermanet al. 1991; Tetlock 1994) concerns, however, BLATANT

PREJUDICEis more closely relatedto CONSERVATISM(r = +.25)

thanis SUBTLEPREJUDICE(r = +.20) in the totalsampleandin three

of the nationalsamples.Moreover,this relationshipemergeswith or with-

out controlsfor the six predictorsof figure 1.

5. Do CONSERVATISMand SUBTLEPREJUDICEsharethe same

predictors?Anotherway to test the Snidermanand Tetlock contention

(1986a, 1986b;Snidermanet al. 1991;Tetlock1994) concerningthe con-

founding of political conservatismwith subtle prejudiceis to compare

theirpredictors.As shownin figure2, SUBTLEPREJUDICEand CON-

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Is Subtle Prejudice Really Prejudice? 61

Mean Effect Size (Cohen's D)

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4-

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

DIVERSE FRIENDS EDUCATION POLITICAL INTEREST GRD

_ Subtle Prejudice Polit. Conservatism

Figure 2. Predictorsof subtleprejudiceand conservatism.Source:

Euro-Barometer 30 survey, 1988.

SERVATISMdiffer sharplyon many variables.The prejudicemeasure

is far more closely associatedthan CONSERVATISMwith less EDU-

CATION, less POLITICALINTEREST,not having INTERGROUP

FRIENDS,and feeling more GROUPRELATIVEDEPRIVATION.

6. By use of confirmatoryfactoranalyses,do the BLATANTandSUB-

TLE PREJUDICEmeasuresfit betterwith one-factoror two-factormod-

els? Criticshold thata one-factormodelis sufficient,while the distinction

between the blatantand subtleforms requiresa two-factormodel. Con-

firmatoryfactor analyses supportthe distinction.In all seven samples,

two-factormodelsprovidesignificantlybetterfits thanone-factormodels

(Pettigrewand Meertens1995, pp. 65-66). Given the tentativenesswith

whichstructuralmodelsmustbe evaluated(Bollen 1989,chap.7), replica-

tion acrossthe seven samplesis vital for comparingthe models.

We testedfourmodels. (1) A one-factormodeltests whetherthe corre-

lationalmatrixof the 20 items fromthe BLATANTand SUBTLEscales

is best representedby one latentfactor-prejudice. (2) An uncorrelated

two-factormodel tests whetherthe dataform two separate,uncorrelated

latent factors-BLATANT and SUBTLE PREJUDICE.(3) The corre-

latedtwo-factormodel tests whetherthe item matrixis best describedby

two separateandcorrelatedlatentfactors.Finally(4), a second-orderfac-

tor model tests whetherthe matrixcan be best accountedfor by two first-

orderfactors(blatantand subtle) that are subordinateto a second-order

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

62 Roel W. Meertens and Thomas F. Pettigrew

Table 2. Predicting Attitudes toward Immigration with Blatant

Prejudice, Subtle Prejudice, and Political Conservatism

RegressionResults

Standardized

Beta t p R

Oppositionto Immigrationscale: .61

BlatantPrejudice .4250 26.12 <.0001

SubtlePrejudice .2170 13.50 <.0001

Conservatism .0953 7.19 <.0001

NominalRemediesscale: .39

BlatantPrejudice -.4250 -21.10 <.0001

SubtlePrejudice .0114 0.61 n.s.

Conservatism .0207 1.34 n.s.

NOTE.-Total sample;N = 3,806.

latent factor (prejudice).For three of the samples, the correlatedtwo-

factor model provided the closest fit. For the remainingsamples, the

second-orderfactormodelprovedbest.Forourpresentpurposes,the most

importantresultis thatboththe one-factorandthe uncorrelatedtwo-factor

models provideinferiorfits in all samples.

7. Is the blatant versus subtle distinction useful? Does it sharpen the

specificationbetweenprejudiceandvariousdependentvariables?We test

these questionsin two interrelatedways. First,we use the entiresample

andpredictthe OPPOSITIONTO IMMIGRATION andNOMINALRE-

MEDIALscales with BLATANTPREJUDICE,SUBTLEPREJUDICE,

andPOLITICALCONSERVATISM. Thenwe look at how the two preju-

dice measuresform three types of respondentswho responddifferently

with our variousmeasuresof attitudestowardimmigrationpolicy.

Table2 providesthe multipleregressionresultsforpredictingimmigra-

tion andremedyattitudeswith our threecriticalmeasuresusing all 3,806

respondents.Forthe OPPOSITIONTO IMMIGRATION scale, the BLA-

TANTPREJUDICEmeasureis the dominantpredictor,butnote thatboth

SUBTLEPREJUDICEand CONSERVATISMsignificantlyadd to the

prediction.Withonly minorexceptions,thispatternis repeatedthroughout

theresultsof the nationalsamples.5Forthe NOMINALREMEDIESscale,

however,only BLATANTPREJUDICEnegativelyrelatesto these mod-

5. In six samples the BLATANT scale was the dominant predictor of OPPOSITION TO

IMMIGRATION. In one sample SUBTLE PREJUDICE was the dominant predictor, and

in two samples CONSERVATISM failed to predict.

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Is Subtle Prejudice Really Prejudice? 63

PERCENTAGE AGREEMENT

100

80

60

40

20

0

Extend Rights Leave As Is Restrict Citizenship Nominal Remedies

| Equalitarians Subtles Z Bigots

Figure 3. Threeprejudicetypes and attitudeson immigrants'rights

and remedies.Source:Euro-Barometer30 survey, 1988.

est proposals.6Conservativesand the subtleyprejudicedtend not to op-

pose these noncommnitting actions.

Anotherway to analyzethesedatais to formthreetypesof respondents.

SUBTLEscalemeansareconsistentlyhigherthanthoseof theBLATANT

scale, because the former's items are more socially acceptable.This

allows an analysis of three types of prejudice.We separatedhigh from

low prejudiceat the centralpoint of the scales, not the empiricalmeans.

One quadrantdropsout, with less than 1 percentof the respondentsscor-

ing high on BLATANTandlow on SUBTLE.Those low or high on both

prejudicescales arethe familiar"equalitarians"and "bigots" long stud-

ied in social psychology.It is the "subtles" who areof specialinterest-

those who score high on the SUBTLEbut low on the BLATANTmea-

sures.Theyrejectcrudeexpressionsof prejudice.Still, they view the new

minoritiesas "a people apart" who violate traditionalvalues and for

whomthey feel no sympathyor admiration.Withthese operationaldefini-

tions, bigots compriseone-sixthof the total sample,subtlesone-half,and

equalitariansone-third.

Figure3 shows for the total samplehow the threetypes respondto the

questionaboutimmigrants'rights-differences thatare consistentacross

6. In two samplesCONSERVATISMaddedsignificantlyto the predictionof the NOMI-

NAL REMEDIESscores-once as a positivepredictorand once as a negativepredictor.

SUBTLEPREJUDICEcontributedpositivelyin only one sample.

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

64 Roel W. Meertens and Thomas F. Pettigrew

PERCENTAGEAGREEMENT

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Send All BackForeignBorn Uneconomic Criminals No Documents All Stay

: Equalitarians 1 Subtles [ Bigots

Figure 4. Threeprejudicetypes and preferredimmigrationpolicies.

Source: Euro-Barometer 30 survey, 1988.

all seven national samples. Bigots are disproportionatelyamong those

who wish to restrictimmigrants'rightsfurther.Equalitariansdispropor-

tionatelyfavorextendingthe rightsof immigrants.By contrast,a plurality

of subtlesassumea middle,ostensiblynonprejudicialposition;they sim-

ply wish to leave the issue as it is. Similarly,the subtlesarefarless likely

than the equalitariansto supportmakingnationalizedcitizenshipeasier

but do join with them in supportingall four of the merely NOMINAL

REMEDIES.

Figure 4 relates the three prejudicetypes to the immigrationpolicy

question.Only bigots in any numberssupportsuch drasticmeasuresas

"sendingback" massive numbersof immigrants-all of them or those

notbornin the countyor arenot contributingto the economy.But a major-

ity of subtlesjoin the bigots in wantingto send "home" those for whom

thereis an ostensiblynonprejudicial reasonto do so-criminals andthose

withouttheirimmigrationdocuments.Moreover,they sharplyreject the

policy of allowing all immigrantsto remainin the country.Note how

many subtles requirea reason to express their oppositionto immigra-

tion-criminality or no documents.We regardthis featureof SUBTLE

PREJUDICEto be crucial.Subtlesfollow the normsagainstblatantex-

pressionof prejudice.But when offeredan ostensiblynonprejudicialrea-

son to express their attitudes,their thresholdfor prejudiceproves lower

than thatof equalitarians.

8. Is theblatantversessubtledistinctionespeciallymeaningfulforthose

groupswhere an antiblatantnormhas takenroot?We take our cue from

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Is Subtle Prejudice Really Prejudice? 65

two recentstudies,both of which used the sameprejudicescales detailed

in the appendix.In theirstudyof educationaleffects on prejudicein Ger-

many, Wagnerand Zick (1995) uncovereda significantinteractionbe-

tweenthe two types of prejudiceandthe educationallevel of theirrespon-

dents. Using a repeated-measuresanalysis of variance with the two

prejudicescales as dependentvariables,they found the differencesbe-

tween the educationalgroupswere significantlylargerfor the BLATANT

thanfor the SUBTLEscale scores.The poorlyeducatedevincedconsider-

ableprejudiceon bothscales,while the well educatedexposedtheirpreju-

dice primarilyon the SUBTLEscale.

In Italy, Arcuriand Boca (1996) used the BLATANTand SUBTLE

scales in their study of the relationshipbetween prejudiceand political

affiliation.They askeda sampleof 500 Italiancitizens for theirattitudes

towardNorthAfricanimmigrantsanduncovereda similarinteraction.On

BLATANTPREJUDICE,left-wingrespondentswere far less prejudiced

thanright-wingrespondents,but, on the SUBTLEPREJUDICEmeasure,

there was no significantdifferencebetweenthe two groups.

We conductedsimilaranalyseson our total sampleas well as each of

the seven nationalsamples.Ourresultsparallelthose of the Germanand

Italianstudies.Younger,well-educated,and left-wing respondentsin all

samplesare distinctivefor theirrelativelylow means on the BLATANT

scale. But their SUBTLEmeans more closely approachthose of older,

less well-educated,and conservativerespondents.Note that this finding

is the oppositeof the Snidermanand Tetlock (1986a, 1986b;Sniderman

et al. 1991;Tetlock 1994) expectations.The SUBTLEPREJUDICEscale

is most useful for detectingthe covertprejudiceof the politicalleft, not

the politicalright.

To displaytheseconsistentresultsgraphically,we dividedthe EDUCA-

TION,AGE andPOLITICALCONSERVATISMvariablesat theirmedi-

ans for each sample.GroupA in figure5 includesthe less-educated,older,

more conservativerespondents;group B comprisesthe bettereducated,

younger,and more left-wing respondents.In every comparisonof figure

5, groupA's meanson bothprejudicescales are significantlyhigherthan

those of groupB. Yet in every case the meandifferencebetweenthe two

groups on SUBTLEPREJUDICEis markedlysmallerthan that of the

mean differenceon BLATANTPREJUDICE.Thus, groupB shows the

widest and groupA the narrowestdiscrepanciesbetweentheirSUBTLE

and BLATANTPREJUDICEscores.7

These findingssupporta normativeinterpretation of the two forms of

prejudice.We posit the existenceamongwell-educated,younger,andleft-

wing Europeansof a strongnormthatproscribesblatantforms of preju-

7. Also observethe large averagediscrepanciesbetween the scale score means for both

Dutch samples.Elsewherewe explorethis findingin detail in orderto shed light on the

uniqueintergrouprelationsof the Netherlands(Pettigrewand Meertens1996).

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

66 Roel W. Meertens and Thomas F. Pettigrew

SUBTLE-BLATANTSCALE MEANS

3-

2

o

0

Total German Dutch:T Dutch:S French:NA French:A UK:Asians UK:W.lnd.

Group A: Blatant Group B: Blatant

[I Group A. Subtle = Group B. Subtle

Figure S. Two normativetypes and subtle-blatantprejudicemeans.

Source:Euro-Barometer 30 survey, 1988.

dice and discriminationagainstoutsiders.Such overtexpressionsviolate

what these groupsconsideracceptable.Yet these groupsdo not perceive

the less directitems of the SUBTLEPREJUDICEscale as invokingthe

anti-BLATANTPREJUDICEnorm.In short,these groupsrejectcrude,

blatantexpressionsof intergrouphostility.Nonetheless,they expressindi-

rect, subtle forms of prejudicethat predictout-grouprejectionin ways

similarto thatof BLATANTPREJUDICE.Note how the cleardistinction

between the two forms of prejudice,blatantand subtle, allows a more

precise descriptionof intergroupattitudesamong such groups.

Conclusions

We have tested the empiricalviability of the subtle prejudiceconcept

with one of the most extensive,cross-nationaldatasets on prejudiceever

collected,andwe have shownthatit can be reliablymeasuredanddistin-

guishedfromblatantprejudice.OurSUBTLEPREJUDICEscaleprovides

consistentfactorialstructuresacross the seven samples.The BLATANT

and SUBTLEscales correlatebetween +.48 and +.70 and are similarly

relatedto predictorvariables.

We consideredin detailclaimsthatsubtleprejudiceis confoundedwith

politicalconservatism.Contraryto such claims, we show thatCONSER-

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Is Subtle Prejudice Really Prejudice? 67

VATISMrelateseitherequallyor more positively with BLATANTthan

SUBTLEPREJUDICEand does not sharethe same predictorswith the

SUBTLE scale. We also used confirmatoryfactor analyses across the

seven samplesto test the one-factormodel called for by critics and two-

factormodels requiredby the blatant-subtledistinction.In every sample,

two-factormodels provedsuperior.

We then demonstratedthe usefulnessof the blatant-subtledistinction.

First, we saw that both prejudicescales, as well as POLITICALCON-

SERVATISM,predictedOPPOSITIONTO IMMIGRATION.But only

BLATANTPREJUDICEpredictedrejectionof NOMINALREMEDIES,

with neitherconservativesnorthe subtletyprejudicedresistingthesenon-

committingactions.

Next we analyzedthe datawith a typologyof respondents:bigots (high

scorerson both prejudicescales), subtles(low scorerson the BLATANT

scale but high on the SUBTLEscale), and equalitarians(low scorerson

both scales). Bigots tendedto favor the restrictionof immigrants'rights,

andequalitarians typicallyfavoredextendingtheirrights,butsubtlesoften

optedfor no change.Only equalitariansin substantialnumberssupported

makingnaturalizationof citizenshipeasier, while subtlesjoined them in

favoringNOMINALREMEDIES.And while bigotspreferredharshpoli-

cies of immigrantexclusion, subtlespreferredostensiblynondiscrimina-

tory methodsof exclusion.

Then we saw how the distinctionsharpensour understandingof in-

tergroupprejudiceamongwell-educatedGermans,left-wingItalians,and

the younger,better-educated, left-wingrespondentsin each of our seven

nationalsamples.Whileeach of thesegroupsis significantlyless blatantly

prejudicedthancomparisongroups,this differencenarrowswhen SUB-

TLE PREJUDICEis measured.This repeatedfindingsuggests a norma-

tive basis for what is seen as socially acceptableand unacceptablein in-

tergroupbeliefs.

Fromtheseconsistentresults,we concludethatsubtleprejudiceis genu-

ine prejudiceand that the distinctionbetweenit and blatantprejudiceis

highly useful. These findingspresenta strikingexample of the conver-

gence of experimentaland surveyevidence.

Two issues remainbefore we can fully conceptualizethis newer type

of prejudice.The first concernsits structuralrelationshipwith the long-

studied,traditionalformof prejudice.Ouranalysessuggestthreepossible

relationships:(1) a second-orderfactormodelwith BLATANTandSUB-

TLE PREJUDICEfirst-orderlatent factorsundera more generallatent

factorof prejudice;(2) a correlatedtwo-factormodel; or (3) a Guttman-

like cumulativemodelin whichSUBTLEPREJUDICEactsas aninterme-

diate level between BLATANTPREJUDICEand tolerance.More work

is neededto evaluatethese possibilities.

A second and relatedissue concernsdifferentforms of the nontradi-

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

68 Roel W. Meertens and Thomas F. Pettigrew

tional types of prejudice (Brown 1995, pp. 232-33). Investigators have

advanced competing terms and operational definitions for the phenome-

non-aversive racism (Kovel 1970; Gaertnerand Dovidio 1986), modem

racism (McConahay 1983; Pettigrew 1989), and symbolic racism (Sears

1988) as well as subtle prejudice (Pettigrew and Meertens 1995). These

various forms are overlapping in content and positively intercorrelated,

yet they appear to tap different levels of subtlety and severity.

A Dutch study suggests that the modem and symbolic racism forms

are the least subtle and aversive racism, epitomized by the avoidance of

out-groups, the most subtle (Kleinpenning and Hagendoom 1993). We

suggest that our measure of SUBTLE PREJUDICE lies between these

other forms. More research, however, is needed.

Appendix

The Blatant and Subtle Prejudice Scales and Their

Five Subscales

THREAT AND REJECTION FACTOR ITEMS: THE BLATANT SCALE

1. West Indianshave jobs thatthe Britishshouldhave (stronglyagree to

stronglydisagree).

2. Most West Indiansliving here who receive supportfrom welfarecould

get along withoutit if they tried (stronglyagree to stronglydisagree).

3. Britishpeople and West Indianscan never be really comfortablewith

each other,even if they are close friends(stronglyagree to stronglydis-

agree).

4. Most politiciansin Britaincare too much aboutWest Indiansand not

enoughaboutthe averageBritishperson(stronglyagree to stronglydis-

agree).

5. West Indianscome from less able races and this explainswhy they are

not as well off as most Britishpeople (stronglyagree to stronglydis-

agree).

6. How differentor similardo you thinkWest Indiansliving here are to

otherBritishpeople like yourself-in how honest they are? (very differ-

ent, somewhatdifferent,somewhatsimilar,or very similar)

INTIMACY FACTOR ITEMS: THE BLATANT SCALE

1. Supposethat a child of yours had childrenwith a personof very differ-

ent color and physicalcharacteristicsthanyour own. Do you thinkyou

would be very bothered,bothered,bothereda little, or not botheredat

all, if your grandchildrendid not physicallyresemblethe people on your

side of the family?

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Is Subtle Prejudice Really Prejudice? 69

2. I would be willing to have sexual relationshipswith a West Indian

(stronglyagree to stronglydisagree)(reversedscoring).

3. I would not mind if a suitablyqualifiedWest Indianpersonwas ap-

pointedas my boss (stronglyagree to stronglydisagree)(reversed

scoring).

4. I would not mind if a West Indianpersonwho had a similareconomic

backgroundas mine joined my close family by marriage(stronglyagree

to stronglydisagree)(reversedscoring).

TRADITIONAL VALUES FACTOR ITEMS: SUBTLE SCALE

1. West Indiansliving here shouldnot push themselveswherethey are not

wanted(stronglyagree to stronglydisagree).

2. Many othergroupshave come to Britainand overcomeprejudiceand

workedtheir way up. West Indiansshoulddo the same withoutspecial

favor (stronglyagree to stronglydisagree).

3. It is just a matterof some people not tryinghardenough.If West Indi-

ans would only try harderthey could be as well off as Britishpeople

(stronglyagree to stronglydisagree).

4. West Indiansliving here teach theirchildrenvalues and skills different

from those requiredto be successfulin Britain(stronglyagree to

stronglydisagree).

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES FACTOR ITEMS: SUBTLE SCALE

How differentor similardo you thinkWestIndiansliving hereareto otherBritish

people like yourself (very different,somewhatdifferent,somewhatsimilar,or

very similar)....

1. In the values that they teach theirchildren?

2. In theirreligiousbeliefs and practices?

3. In their sexual values or sexual practices?

4. In the languagethatthey speak?

AFFECTIVE PREJUDICE FACTOR ITEMS: SUBTLE SCALE

Have you ever felt the following ways about West Indiansand their families

living here (very often, fairly often, not too often, or never)?

1. How often have you felt sympathyfor West Indiansliving here? (re-

versed scoring)

2. How often have you felt admirationfor West Indiansliving here? (re-

versed scoring)

References

Allport,GordonW. 1954. TheNatureof Prejudice.Reading,MA: Addison-Wesley.

Arcuri,Luciano,and StepanoBoca. 1996. "Pregiudizioe affiliazionepolitica:Destrae

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

70 Roel W. Meertens and Thomas F. Pettigrew

sinistradi fronteall'immigrazionedal terzo mondo" (Prejudiceand political

affiliation:Right and left confrontedwith immigrationfrom the ThirdWorld).In

Psicologia e Politica, ed. Paolo Legrenziand VittorioGirotto,pp. 241-74. Milan,

Italy:RaffaelloCortina.

Barker,Martin.1984. TheNew Racism:Conservativesand the Ideologyof the Tribe.

Frederick,MD: Aletheia.

Bergmann,Werner,and RainerErb. 1986. "Kommunikationslatenz: Moralund

OffentlicheMeining" (Latentcommunication:Moraland public meaning).Kolner

Zeitschriftfur Soziologieund Sozialpsychologie38:223-46.

Bollen, KennethA. 1989. StructuralEquationswith LatentVariables.New York:

Wiley.

Brown,Rupert.1995. Prejudice:Its Social Psychology.Oxford:Blackwell.

Crosby,Faye J., SusanBromley,and LeonardSaxe. 1980. "RecentUnobtrusive

Studiesof Black and White Discriminationand Prejudice:A LiteratureReview."

PsychologicalBulletin87:546-63.

Dijker,AntonJ. M. 1987. "EmotionalReactionsto EthnicMinorities."European

Journalof Social Psychology 17:305-25.

Dovidio, JohnF., JeffreyA. Mann,and SamuelL. Gaertner.1989. "Resistanceto

AffirmativeAction:The Implicationsof AversiveRacism." In AffirmativeAction in

Perspective,ed. FletcherA. Blanchardand Faye J. Crosby,pp. 83-102. New York:

Springer.

Essed, Philomena.1984. AlledaagsRacisme(Everydayracism).Amsterdam:Sara.

Freriks,Paul. 1990. "FranseAnti-RacistenWillen HandenVuil Maken" (French

antiracistswant to take action).De Volkskrant,May 1, p. 2.

Gaertner,SamuelL., and JohnF. Dovidio. 1986. "The AversiveFormof Racism." In

Prejudice, Discrimination, and Racism: Theory and Research, ed. John F. Dovidio

and SamuelL. Gaertner,pp. 61-89. New York:AcademicPress.

Jacobson,CardellK. 1985. "Resistanceto AffirmativeAction." Journalof Conflict

Resolution29:306-29.

Kleinpenning,Gerard,and Louk Hagendoorn.1993. "Formsof Racismand the

CumulativeDimensionof EthnicAttitudes."Social PsychologyQuarterly56:21-36.

Kovel, Joel. 1970. WhiteRacism:A Psychohistory.New York:Pantheon.

McClendon,McKee J. 1985. "Racism,RationalChoices, and White Oppositionto

Racial Change:A Case Studyof Busing." Public OpinionQuarterly49:214-33.

McConahay,JohnB. 1982. "Is It the Buses or the Blacks?Self-Interestversus

SymbolicRacismas Predictorsof Oppositionto Busing in Louisville." Journalof

Politics 44:692-720.

. 1983. "Modem Racismand Modem Discrimination:The Effects of Race,

RacialAttitudes,and Contexton SimulatedHiringDecisions." Personalityand

Social PsychologyBulletin9:551-58.

Pettigrew,ThomasF. 1989. "The Natureof Modem Racismin the U.S." Revue

Internationalede PsychologieSociale 2:291-303.

Pettigrew,ThomasF., and Roel W. Meertens.1995. "Subtleand BlatantPrejudicein

WesternEurope."EuropeanJournalof Social Psychology25:57-75.

. 1996. "The VerzuilingPuzzle:UnderstandingDutchIntergroupRelations."

CurrentPsychology 15:3-13.

Reif, Karlheinz,and Anna Melich. 1991. Eurobarometer30: Immigrantsand Out-

Groupsin WesternEurope,October-November 1988. Ann Arbor,MI: Inter-

UniversityConsortiumfor Politicaland Social Research.

Rokeach,Milton. 1960. The Openand ClosedMind.New York:Basic.

Sears,David 0. 1988. "SymbolicRacism." In EliminatingRacism:Profiles in

Controversy,ed. Phyllis A. Katz and DalmasA. Taylor,pp. 53-84. New York:

Plenum.

Sniderman,Paul M., ThomasPiazza, PhilipE. Tetlock,and Ann Kendrick.1991. "The

New Racism."AmericanJournalof Political Science 35:423-47.

Sniderman,Paul M., and Philip E. Tetlock. 1986a. "Reflectionson AmericanRacism."

Journalof Social Issues 42:173-87.

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Is Subtle Prejudice Really Prejudice? 71

. 1986b. "SymbolicRacism:Problemsof Motive Attributionin Political

Debate." Journal of Social Issues 42:129-50.

Tetlock,PhilipE. 1994. "PoliticalPsychologyor PoliticizedPsychology:Is the Road

to Hell Paved with Good MoralIntentions?"Political Psychology 15:509-30.

Vanneman,Reeve, and ThomasF. Pettigrew.1972. "Race and RelativeDeprivationin

the UrbanUnited States." Race 13:461-86.

Wagner,Ulrich, and AndriasZick. 1995. "The Relationof FormalEducationto Ethnic

Prejudice:Its Reliability,Validity,and Explanation."EuropeanJournalof Social

Psychology 25:41-56.

This content downloaded from 131.94.16.10 on Tue, 10 Sep 2013 23:33:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

También podría gustarte

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2104)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Ebook PDF Business Analytics 4th Edition by Jeffrey D Camm PDFDocumento41 páginasEbook PDF Business Analytics 4th Edition by Jeffrey D Camm PDFshirley.gallo35795% (42)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- A Conservative Revolution in Publishing - BourdieuDocumento32 páginasA Conservative Revolution in Publishing - BourdieuManuel González PosesAún no hay calificaciones

- S2 Mark Scheme Jan 2004 - V1Documento4 páginasS2 Mark Scheme Jan 2004 - V1Shane PueschelAún no hay calificaciones

- Research 2 - Lesson 1Documento41 páginasResearch 2 - Lesson 1yekiboomAún no hay calificaciones

- Rph-Historical Critism Lesson 2Documento3 páginasRph-Historical Critism Lesson 2Rosmar AbanerraAún no hay calificaciones

- A Y A: I I D A F S P ?: Gility in Oung Thletes S TA Ifferent Bility ROM Peed and OwerDocumento9 páginasA Y A: I I D A F S P ?: Gility in Oung Thletes S TA Ifferent Bility ROM Peed and OwerVladimir PokrajčićAún no hay calificaciones

- Kapl Internship File EditedDocumento39 páginasKapl Internship File EditedDilip ShivshankarAún no hay calificaciones

- A Framework For Hybrid Warfare Threats Challenges and Solutions 2167 0374 1000178Documento13 páginasA Framework For Hybrid Warfare Threats Challenges and Solutions 2167 0374 1000178Tuca AlinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Ndamba Project ProposalDocumento15 páginasNdamba Project ProposalCharity MatibaAún no hay calificaciones

- COM668 - 07 Assessment Overview - Semester 1Documento29 páginasCOM668 - 07 Assessment Overview - Semester 1leo2457094770Aún no hay calificaciones

- Item Analysis and Validation: Ed 106 - Assessment in Learning 1 AY 2022-2023Documento8 páginasItem Analysis and Validation: Ed 106 - Assessment in Learning 1 AY 2022-2023James DellavaAún no hay calificaciones

- Portakabin Emerging MarketDocumento2 páginasPortakabin Emerging MarketWint Wah Hlaing100% (1)

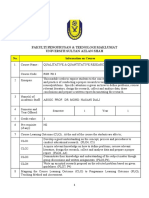

- Fakulti Pengurusan & Teknologi Maklumat Universiti Sultan Azlan ShahDocumento4 páginasFakulti Pengurusan & Teknologi Maklumat Universiti Sultan Azlan ShahAlice ArputhamAún no hay calificaciones

- Travel Demand ForecastingDocumento11 páginasTravel Demand ForecastingJosiah FloresAún no hay calificaciones

- Math 30210 - Introduction To Operations ResearchDocumento7 páginasMath 30210 - Introduction To Operations ResearchKushal BnAún no hay calificaciones

- Cognitive ObjectivesDocumento9 páginasCognitive ObjectivesJennifer R. JuatcoAún no hay calificaciones

- MB0048 Operation Research Assignments Feb 11Documento4 páginasMB0048 Operation Research Assignments Feb 11Arvind KAún no hay calificaciones

- Industry Perspective FDA Draft ValidationDocumento6 páginasIndustry Perspective FDA Draft ValidationOluwasegun ModupeAún no hay calificaciones

- A Study On Consumer Awareness On Amway ProductsDocumento8 páginasA Study On Consumer Awareness On Amway ProductsSenthilkumar PAún no hay calificaciones

- Artificial Intelligence in Breast ImagingDocumento10 páginasArtificial Intelligence in Breast ImagingBarryAún no hay calificaciones

- Curr - DevDocumento13 páginasCurr - DevPaulAliboghaAún no hay calificaciones

- Conception of A Manual Brick Machine PDFDocumento57 páginasConception of A Manual Brick Machine PDFamanuel admasuAún no hay calificaciones

- Impact of Celebrity Endorsement....... 1Documento87 páginasImpact of Celebrity Endorsement....... 1Amar RajputAún no hay calificaciones

- Educ 6 Prelim Module 1Documento18 páginasEduc 6 Prelim Module 1Dexter Anthony AdialAún no hay calificaciones

- Braza FinalDocumento38 páginasBraza FinalGemver Baula BalbasAún no hay calificaciones

- 05classification Rule MiningDocumento56 páginas05classification Rule Mininghawariya abelAún no hay calificaciones

- Coherent Modeling and Forecasting of Mortality Patterns ForDocumento14 páginasCoherent Modeling and Forecasting of Mortality Patterns ForAldair BsAún no hay calificaciones

- EDID 6503 Assignment 3Documento12 páginasEDID 6503 Assignment 3Tracy CharlesAún no hay calificaciones

- Fidia Oktarisa, 2023Documento14 páginasFidia Oktarisa, 2023AUFA DIAZ CAMARAAún no hay calificaciones

- FinalDocumento8 páginasFinalMelvin DanginAún no hay calificaciones