Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Asd

Cargado por

SuperfixenDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Asd

Cargado por

SuperfixenCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Identifying, Screening, & Assessing Acknowledgement

Autism at School

Adapted from

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP Brock, S. E., Jimerson, S. R., & Hansen,

California State University Sacramento R. L. (2006). Identifying, assessing,

and treating autism at school. New

NASP & AHI Summer Conference York: Springer.

Chicago, IL - July 28, 2006

Presentation Outline Introduction: Reasons for Increased Vigilance

z Introduction: Reasons for Increased Vigilance z Autistic spectrum disorders are much more

z Diagnostic Classifications and Special common than previously suggested.

Education Eligibility 60 (vs. 4 to 6) per 10,000 in the general population

(Chakrabarit & Fombonne, 2001).

z School Psychologist Roles, Responsibilities,

600% increase in the numbers served under the

and Limitations

autism IDEA eligibility classification (U.S. Department of Education,

z Case Finding 2003).

z Screening and Referral 95% of school psychologists report an increase in the

number of students with ASD being referred for

z Assessment: Diagnostic and Psycho-educational assessment (Kohrt, 2004).

Evaluation

Explanations for Changing ASD Increased Prevalence in Special

Rates in the General Population Education (U.S. Department of Education, 2003)

z Changes in diagnostic criteria. Total Number of Student Classified as Autistic and Eligible for

Special Education Under IDEA by Age Group

z Heightened public awareness of autism.

100,000

z Increased willingness and ability to diagnose

80,000

autism.

60,000

z Availability of resources for children with 40,000

autism. 20,000

z Yet to be identified environmental factors. 0

1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

6 11 years 12 17 years 18 21 years

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 1

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Explanations for Changing ASD Increased Prevalence in Special

Rates in Special Education Education (U.S. Department of Education, 2005)

School Population Rates of Mental Retardation and Autism

z Classification substitution Special Education Eligibility Classifications: 1991 to 2004

IEP teams have become better able to identify 12

Rate per 1,000 Students

students with autism. 10 4

3 9.9 5 2 6

9 9.4 9.5 9.4 9.4 9.3

8 7 1

9.3 9.1 9.2

Autism is more acceptable in todays schools than is 8

9.1 9.0 8.8

1

8.6

7

8.4

3

the diagnosis of mental retardation. 6

The intensive early intervention services often made 4

available to students with autism are not always

2.51

2.13

1.79

2

1.49

1.21

offered to the child whose primary eligibility

1.01

0.84

0.67

0.55

0.48

0.38

0.32

0.25

0.09

0

classification is mental retardation.

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

Year

Mental Retardation Autism

Reasons for Increased Vigilance Reasons for Increased Vigilance

z Autism can be identified early in development, z Not all cases of autism will be identified before

and school entry.

Average Age of Autistic Disorder identification is 5 1/2

z Early intervention is an important determinant years of age.

of the course of autism. Average Age of Aspergers Disorder identification is

11 years of age Howlin and Asgharian (1999).

Reasons for Increased Vigilance Presentation Outline

z Most children with autism are identified by school z Introduction: Reasons for Increased Vigilance

resources. z Diagnostic Classifications and Special

Only three percent of children with ASD are identified Education Eligibility

solely by non-school resources.

z School Psychologist Roles, Responsibilities,

All other children are identified by a combination of

school and non-school resources (57 %), or by school

and Limitations

resources alone (40 %) Yeargin-Allsopp et al. (2003). z Case Finding

z Screening and Referral

z Assessment: Diagnostic and Psycho-educational

Evaluation

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 2

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Evolution of the Term Autism Evolution of the Term Autism

z First used by Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler in 1911. z In 1980, infantile autism was first included in the third

Derived from the Greek autos (self) and ismos (condition), Bleuler edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

used the term to describe the concept of turning inward on ones

self and applied it to adults with schizophrenia. (DSM), within the category of Pervasive

z In 1943 Leo Kanner first used the term infantile autism to Developmental Disorders.

describe a group of children who were socially isolated, were z Also occurring at about this time was a growing

behaviorally inflexible, and who had impaired communication. awareness that Kranners autism (also referred to a

z Initially viewed as a consequence of poor parenting, it was not classic autism) is the most extreme form of a

until the 1960s, and recognition of the fact that many of these spectrum of autistic disorders.

children had epilepsy, that the disorder began to be viewed as

having a neurological basis. z Autistic Disorder is the contemporary classification

used since the revision of DSMs third edition (APA,

1987).

Special Education Eligibility:

Diagnostic Classifications Proposed IDEIA Regulations

Pervasive Developmental Disorders z IDEIA 2004 Autism Classification

P.L. 108-446, Individuals with Disabilities Education

Autistic Disorder In this workshop the Improvement Act (IDEIA), 2004

Proposed USDOE Regulations for IDEA 2004 [ 300.8(c)(1)]

terms Autism, or

z Autism means a developmental disability significantly affecting

Asperger's Disorder Autistic Spectrum verbal and nonverbal communication and social interaction,

generally evident before age three, that adversely affects a childs

Disorders (ASD) will be education performance. Other characteristics often associated with

PDD-NOS used to indicate these autism are engagement in repetitive activities and stereotypical

PDDs. movements, resistance to environmental change or change in daily

routines, and unusual responses to sensory experiences. (i)

Rett's Disorder Autism does not apply if a childs educational performance is

adversely affected primarily because the child has an emotional

disturbance, as defined in paragraph (c)(4) of this section. (ii) A

Childhood Disintegrative child who manifest the characteristics of autism after age three

Disorder could be identified as having autism if the criteria in paragraph

(c)(1)(i) of this section are satisfied.

Special Education Eligibility Special Education Eligibility

z For special education eligibility purposes distinctions z However, it is less clear if students with milder forms

among PDDs may not be relevant. of ASD are always eligible for special education.

z While the diagnosis of Autistic Disorder requires z Adjudicative decision makers almost never use the

differentiating its symptoms from other PDDs, DSM IV-TR criteria exclusively or primarily for

determining whether the child is eligible as autistic

Shriver et al. (1999) suggest that for special (Fogt et al.,2003).

education eligibility purposes the federal definition

z While DSM IV-TR criteria are often considered in

of autism was written sufficiently broad to hearing/court decisions, IDEA is typically

encompass children who exhibit a range of acknowledged as the controlling authority.

characteristics (p. 539) including other PDDs. z When it comes to special education, it is state and

federal education codes and regulations (not DSM

IV-TR) that drive eligibility decisions.

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 3

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

School Psychologist Roles,

Presentation Outline Responsibilities, and Limitations

z Introduction: Reasons for Increased Vigilance 1. School psychologists need to be more

z Diagnostic Classifications and Special vigilant for symptoms of autism among the

Education Eligibility students that they serve, and better

prepared to assist in the process of

z School Psychologist Roles, Responsibilities,

identifying these disorders.

and Limitations

z Case Finding

z Screening and Referral

z Assessment: Diagnostic and Psycho-educational

Evaluation

School Psychologist Roles, School Psychologist Roles,

Responsibilities, and Limitations Responsibilities, and Limitations

2. Case Finding 3. Screening

All school psychologists should be expected to All school psychologists should be prepared to participate

in the behavioral screening of the student who has risk

participate in case finding (i.e., routine factors and/or displays warning signs of autism (i.e., able to

developmental surveillance of children in the general conduct screenings to determine the need for diagnostic assessments).

population to recognize risk factors and identify All school psychologists should be able to distinguish

warning signs of autism). between screening and diagnosis.

z This would include training general educators to identify the 4. Diagnosis

risk factors and warning signs of autism. Only those school psychologists with appropriate training and

supervision should diagnose a specific autism spectrum

disorder.

School Psychologist Roles,

Responsibilities, and Limitations Presentation Outline

5. Special Education Eligibility z Introduction: Reasons for Increased Vigilance

All school psychologists should be expected to

conduct the psycho-educational evaluation that is a z Diagnostic Classifications and Special

part of the diagnostic process and that determines Education Eligibility

educational needs.

NOTE: z School Psychologist Roles, Responsibilities,

z The ability to conduct such assessments will require school and Limitations

psychologists to be knowledgeable of the accommodations

necessary to obtain valid test results when working with the z Case Finding

child who has an ASD.

z Screening and Referral

z Assessment: Diagnostic and Psycho-educational

Evaluation

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 4

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Case Finding Case Finding

z Known Risk Factors z Currently there is no substantive evidence

High Risk supporting any one non-genetic risk factor for

z Having an older sibling with autism. ASD.

Moderate Risk z However, given that there are likely different

z The diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis, fragile X, or epilepsy. causes of ASD, it is possible that yet to be

z A family history of autism or autistic-like behaviors.

identified non-heritable risk factors may prove

to be important in certain subgroups of

individuals with this disorder.

Case Finding Case Finding

z Infant & Preschooler Warning Signs z Infant & Preschooler Warning Signs

Absolute indications for an autism screening Absolute indications for an autism screening

No big smiles or other joyful expressions by 6 months.b No 2-word spontaneous (nonecholalic) phrases by 24

months.a, b

No back-and-forth sharing of sounds, smiles, or facial

Failure to attend to human voice by 24 months.c

expressions by 9 months.b

Failure to look at face and eyes of others by 24 months.c

No back-and-forth gestures, such as pointing, showing,

Failure to orient to name by 24 months.c

reaching or waving bye-bye by 12 months.a,b

Failure to demonstrate interest in other children by 24

No babbling at 12 months.a, b months.c

No single words at 16 months.a, b Failure to imitate by 24 months.c

Any loss of any language or social skill at any age.a, b

Sources: aFilipek et al., 1999; bGreenspan, 1999; and cOzonoff, 2003. Sources: aFilipek et al., 1999; bGreenspan, 1999; and cOzonoff, 2003.

Case Finding Case Finding

z School-Age Children Warning Signs z School-Age Children Warning Signs

Social/Emotional Concerns Communication Concerns

z Poor at initiating and/or sustaining activities and friendships with

z Unusual tone of voice or speech (seems to have an accent or

peers

monotone, speech is overly formal)

z Play/free-time is more isolated, rigid and/or repetitive, less interactive

z Overly literal interpretation of comments (confused by

z Atypical interests and behaviors compared to peers

sarcasm or phrases such as pull up your socks or looks can

z Unaware of social conventions or codes of conduct (e.g., seems

kill)

unaware of how comments or actions could offend others)

z Excessive anxiety, fears or depression z Atypical conversations (one-sided, on their focus of interest or

on repetitive/unusual topics)

z Atypical emotional expression (emotion, such as distress or

affection, is significantly more or less than appears appropriate for z Poor nonverbal communication skills (eye contact, gestures,

the situation) etc.)

Sources: Adapted from Aspergers Syndrome A Guide for Parents and Professionals (Attwood, 1998), Sources: Adapted from Aspergers Syndrome A Guide for Parents and Professionals (Attwood, 1998), Diagnostic

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (APA, 1994), and The Apserger Syndrome and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (APA, 1994), and The Apserger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale

Diagnostic Scale (Myles, Bock and Simpson, 2000) (Myles, Bock and Simpson, 2000)

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 5

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Case Finding Presentation Outline

z School-Age Children Warning Signs

z Introduction: Reasons for Increased Vigilance

Behavioral Concerns

z Excessive fascination/perseveration with a particular topic, z Diagnostic Classifications and Special

interest or object Education Eligibility

z Unduly upset by changes in routines or expectations

z School Psychologist Roles, Responsibilities,

z Tendency to flap or rock when excited or distressed

z Unusual sensory responses (reactions to sound, touch,

and Limitations

textures, pain tolerance, etc.) z Case Finding

z History of behavioral concerns (inattention, hyperactivity,

aggression, anxiety, selective mute) z Screening and Referral

z Poor fine and/or gross motor skills or coordination z Assessment: Diagnostic and Psycho-educational

Sources: Adapted from Aspergers Syndrome A Guide for Parents and Professionals (Attwood, 1998), Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (APA, 1994), and The Apserger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale Evaluation

(Myles, Bock and Simpson, 2000)

Adaptation of Filipek et al.s (1999) Algorithm

for the Process of Diagnosing Autism Screening and Referral

Case

Finding z Screening is designed to help determine the

YES Screening Indicated NO Continue to monitor development

need for additional diagnostic assessments.

z In addition to the behavioral screening (which

Autism

Screening at school should typically be provided by the

school psychologist), screening should

Autism Inicated Refer for assessment as indicted

YES NO

include medical testing (lead screening) and

Diagnostic

a complete audiological evaluation.

Assessment

Psych-educational

Assessment

Behavioral Screening of Infants

Behavioral Screening for ASD and Preschoolers

z School psychologists are exceptionally well qualified z CHecklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT)

to conduct the behavioral screening of students Designed to identify risk of autism among 18-month-olds

suspected to have an ASD. Takes 5 to 10 minutes to administer,

z Several screening tools are available Consists of 9 questions asked of the parent and 5 items

z Initially, most of these tools focused on the that are completed by the screeners direct observation of

identification of ASD among infants and the child.

preschoolers. 5 items are considered to be key items. These key items,

z Recently screening tools useful for the identification assess joint attention and pretend play.

of school aged children who have high functioning If a child fails all five of these items they are considered to

autism or Aspergers Disorder have been developed. be at high risk for developing autism.

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 6

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

CHecklist for Autism in Toddlers CHecklist for Autism in Toddlers

CHAT Section B: general practitioner or health visitor observation

CHAT SECTION A: History: Ask parent

i. During the appointment, has the child made eye contact with your? YES NO

1. Does your child enjoy being swung, bounced on your knee, etc.? YES NO

ii. Get childs attention, then point across the room at an interesting object YES NO*

2. Does your child take an interest in other children? YES NO and say Oh look! Theres a [name of toy]. Watch childs face. Does the

child look across to see what you are point at?

3. Does your child like climbing on things, such as up stairs? YES NO iii. Get the childs attention, then give child a miniature toy cup and teapot YES NO

and say Can you make a cup of tea? Does the child pretend to pour out

4. Does your child enjoy playing peek-a-boo/hide-and-seak? YES NO tea, drink it, etc.?

iv. Say to the child Where is the light?, or Show me the light. Does the YES NO

child POINT with his/her index finger at the light?

5. Does your child ever PRETEND, for example to make a cup of tea using YES NO

v. Can the child build a tower of bricks? (if so how many?) (No. of YES NO

a toy cup and teapot, or pretend other things?

bricks:)

6. Does your child ever use his/her index finger to point to ASK for something? YES NO * To record Yes on this item, ensure the child has not simply looked at your hand, but has

actually looked at the object you are point at.

7. Does your child ever use his/her index finger to point to indicate YES NO

If you can elicit an example of pretending in some other game, score a Yes on this item.

INTEREST in something? Repeat this with Wheres the teddy? or some other unreachable object, if child does not

8. Can your child play properly with small toys (e.g., cars or bricks) without YES NO understand the word light. To record Yes on this item, the child must have looked up at your

just mouthing, fiddling or dropping them? face around the time of pointing.

9. Does your child ever bring objects over to you (parent) to SHOW your YES NO

something? Scoring: High risk for Autism: Fails A5, A7, Bii, Biii, and Biv

Medium risk for autism group: Fails A7, Biv (but not in maximum risk group)

Low risk for autism group (not in other two risk groups)

From Baron-Cohen et al (1996, p. 159).

Behavioral Screening of Infants

CHecklist for Autism in Toddlers and Preschoolers

z Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-

http://www.autisticsociety.org/article136.html CHAT)

Designed to screen for autism at 24 months of age.

More sensitive to the broader autism spectrum.

Uses the 9 items from the original CHAT as its basis.

Adds 14 additional items (23-item total).

Unlike the CHAT, however, the M-CHAT does not require

the screener to directly observe the child.

Makes use of a Yes/No format questionnaire.

Yes/No answers are converted to pass/fail responses by

the screener.

A child fails the checklist when 2 or more of 6 critical

items are failed or when any three items are failed.

Behavioral Screening of Infants Modified Checklist for Autism in

and Preschoolers Toddlers

Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT)

z Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) Please fill out the following about how your child usually is. Please try to answer every question. If the

behavior is rare (e.g., youve seen it once or twice), please answer as if the child does not do it.

The M-CHAT was used to screen 1,293 18- to 30- 1. Does your child enjoy being swung, bounced on your knee, etc.? Yes No

2. Does your child take an interest in other children? Yes No

month-old children. 58 were referred for a

3. Does your child like climbing on things, such as up stairs? Yes No

diagnostic/developmental evaluation. 39 were 4. Does your child enjoy playing peek-a-boo/hide-and-seek? Yes No

diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (Robins 5. Does your child ever pretend, for example, to talk on the phone or No

take care of

et al., 2001). 6. Does your child ever use his/her index finger to point, to ask for No

something?

Does your child ever use his/her index finger to point, to indicate

Will result in false positives. 7.

interest in

No

8. Can your child play properly with small toys (e.g. cars or bricks) No

without just

Data regarding false negative is not currently 9. Does your child ever b ring objects over to you (parent) to show No

you something?

available, but follow-up research to obtain such is 10. Does your child look you in the eye for more than a second or two? Yes No

currently underway. 11. Does your child ever seem oversensitive to noise? (e.g., plugging ears) Yes No

Robins et al. (2001, p. 142)

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 7

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Modified Checklist for Autism in Modified Checklist for Autism in

Toddlers Toddlers

Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT)

Please fill out the following about how your child usually is. Please try to answer every question. If the M-CHAT Scoring Instructions

behavior is rare (e.g., youve seen it once or twice), please answer as if the child does not do it.

13. Does your child imitate you? (e.g., you make a face-will your child No A child fails the checklist when 2 or more critical items are failed OR when any three items are

imitate it?)

failed. Yes/no answers convert to pass/fail responses. Below are listed the failed responses for each

14 Does your child respond to his/her name when you call? Yes No

item on the M-CHAT. Bold capitalized items are CRITICAL items.

15. If you point at a toy across the room, does your child look at it? Yes No

Not all children who fail the checklist will meet criteria for a diagnosis on the autism spectrum.

16. Does your child walk? Yes No

Howev er, children who fail the checklist should be evaluated in more depth by the physician or

17. Does your child look at things you are looking at? Yes No referred for a developmental evaluation with a specialist.

18. Does your child make unusual finger movements near his/her face? Yes No

1. No 6. No 11. Yes 16. No 21. No

19. Does your child try to attract your attention to his/her own activity? Yes No 2. NO 7. NO 12. No 17. No 22. Yes

3. No 8. No 13. NO 18. Yes 23. No

20. Have you ever wondered if your child is deaf? Yes No

4. No 9. NO 14. NO 19. No

21. Does your child understand what people say? Yes No 5. No 10. No 15. NO 20. Yes

22. Does your child sometimes stare at nothing or wander with no No

purpose?

23. Does your child look at your face to check your reaction when faced No

with

Robins et al. (2001, p. 142) Robins et al. (2001)

Modified Checklist for Autism in Behavioral Screening of School

Toddlers Age Children

z Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ)

The 27 items rated on a 3-point scale.

http://www.firstsigns.org/downloads/m-chat.PDF Total score range from 0 to 54.

Items address social interaction, communication,

restricted/repetitive behavior, and motor clumsiness and other

associated symptoms.

The initial ASSQ study included 1,401 7- to 16-year-olds.

z Sample mean was 0.7 (SD 2.6).

z Asperger mean was 26.2 (SD 10.3).

A validation study with a clinical group (n = 110) suggests the

ASSQ to be a reliable and valid parent and teacher screening

instrument of high-functioning autism spectrum disorders in a

clinical setting (Ehlers, Gillber, & Wing, 1999, p. 139).

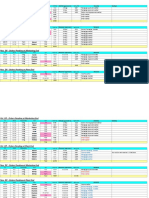

Behavioral Screening of School Autism Spectrum Screening

Age Children Questionnaire

Different parent and teacher ASSQ cutoff scores with true positive rate (% of children with an ASD

z Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ) who were rated at a given score), false positive rate (% of children without an ASD who we re rated

at a given score), and the likelihood ratio a given score predicting and ASD.

Two separate sets of cutoff scores are suggested.

z Parents, 13; Teachers, 11: = socially impaired children Cutoff Score True Positive Rate (%) False Positive Rate (%) Likelihood Ratio

Low risk of false negatives (especially for milder cases of ASD). Parent

7 95 44 2.2

High rate of false positives (23% for parents and 42% for teachers). 13 91 23 3.8

Not unusual for children with other disorders (e.g., disruptive behavior 15 76 19 3.9

disorders) to obtain ASSQ scores at this level. 16 71 16 4.5

Used to suggest that a referral for an ASD diagnostic assessment, 17 67 13 5.3

while not immediately indicated, should not be ruled out. 19 62 10 5.5

20 48 8 6.1

z Parents, 19; Teachers, 22: = immediate ASD diagnostic referral. 22 42 3 12.6

False positive rate for parents and teachers of 10% and 9 % Teacher

respectively. 9 95 45 2.1

The chances are low that the student who attains this level of ASSQ 11 90 42 2.2

cutoff scores will not have an ASD. 12 85 37 2.3

15 75 27 2.8

Increases the risk of false negatives. 22 70 9 7.5

24 65 7 9.3

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 8

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Behavioral Screening of School Childhood Asperger Syndrome

Age Children Test

Childhood Asperger Sy ndrome Test (CAST)

z Childhood Asperger Syndrome Test (CAST) 1. Does s/he join in playing g ames with other children easily? YES NO

Scott, F. A., Baron-Cohen, S., Bolton, P., & Brayne, C. (2002). 2. Does s/he co me up to you spontaneou sly for a chat? YES NO

The CAST (Childhood Asperger Syndrome Test). Autism, 6, 9- 3. Was s/he speaking by 2 yea rs old? YES NO

4. Does s/he en joy sports? YES NO

31.

5. Is it important to him/her to fit in with the peer group? YES NO

z A screening for mainstream primary grade (ages 4 through 11 6. Does s/he app ear to notice unusual details that others miss? YES NO

years) children. 7. Does s/he tend to take things literally? YES NO

z Has 37 items, with 31 key items contributing to the childs total 8. When s/he was 3 yea rs old, did s/her spend a lot of time pretending (e.g. p lay-

acting begin a superhero, or holding a teddys tea parties)?

YES NO

score. 9. Does s/he like to do things over and over aga in, in the same way all the time? YES NO

z The 6 control items assess general development. 10. Does s/he find it easy to interact with other children? YES NO

11. Can s/he keep a two-way conve rsation go ing? YES NO

z With a total possible score of 31, a cut off score of 15 NO

12. Can s/he read approp riately for his/her age? YES NO

responses was found to correctly identify 87.5 (7 out of 8) of the

13. Does s/he mostly have the same interest as his/her peers? YES NO

cases of autistic spectrum disorders. 14. Does s/he hav e an interest, which takes up so much time that s/he does little

YES NO

else?

z Rate of false positives is 36.4%. 15. Does s/he hav e friends, rather than just acquaintances? YES NO

z Rate of false negatives is not available 16. Does s/he often bring you things s/he is interested in to show you? YES NO

From Scott et al. (2002, p. 27)

Childhood Asperger Syndrome Childhood Asperger Syndrome

Test Test

17. Does s/he en joy joking around? YES NO

18. Does s/he have difficulty understanding the rules for polite behavior? YES NO

19. Does s/he appear to have an unusual memory for details? YES NO

http://www.autismresearchcentre.com/tests/cast_test.asp

20. Is his/her voice unusual (e.g., ove rly adult, flat, or very monotonous)? YES NO

21. Are people important to him/her? YES NO

22. Can s/he dress him/herself? YES NO

23. Is s/he good a t turn-taking in conve rsation? YES NO

24. Does s/he play imaginatively with other children, and engage in role-play? YES NO

25. Does s/he often do or say things that are tactless or so cially inappropriate? YES NO

26. Can s/he coun t to 50 without leaving out any numbers? YES NO

27. Doe s s/he make normal eye -contact? YES NO

28. Doe s s/he have any unusu al and rep etitive move ments? YES NO

29. Is his/her social behaviour very one -sided and always on his/her own terms? YES NO

30. Doe s s/he sometimes say youor s/hewhen s/he means I? YES NO

31. Doe s s/he prefer imaginative activities such as play-acting or story-telling,

YES NO

rather than numbers or lists of facts?

32. Doe s s/he sometimes lose the listener bec ause of no t explaining what s/he is

YES NO

talking about?

33. Can s/he ride a bicycle (even if with stabilizers)? YES NO

34. Doe s s/he try to impose routines on h im/herself, or on others, in such a way

YES NO

that is causes problems?

35. Doe s s/he care how s/he is perceived by the rest of the group? YES NO

36. Doe s s/he often turn the conversations to his/her favo rite subject rather than

YES NO

following wha t the other person wants to talk about?

37. Doe s s/he have odd or unusua l phrases? YES NO

From Scott et al. (2002, pp. 27-28)

Behavioral Screening of School Behavioral Screening of School

Age Children Age Children

z Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) z Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ)

Two forms of the SCQ: a Lifetime and a Current form.

z Current ask questions about the childs behavior in the past 3-

months, and is suggested to provide data helpful in

understanding a childs everyday living experiences and

evaluating treatment and educational plans

z Lifetime ask questions about the childs entire developmental

history and provides data useful in determining if there is need

for a diagnostic assessment.

Consists of 40 Yes/No questions asked of the parent.

The first item of this questionnaire documents the childs

ability to speak and is used to determine which items will be

used in calculating the total score.

Rutter, M., LeCouteur, A., & Lord, C. (2003). Social Communication Questionnaire. Los Angeles, CA:

Western Psychological Services.

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 9

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Behavioral Screening of School Behavioral Screening of School

Age Children Age Children

z Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) z Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ)

An AutoScore protocol converts the parents While it is not particularly effective at distinguishing among

Yes/No responses to scores of 1 or 0. the various ASDs, it has been found to have good

discriminative validity between autism and other disorders

The mean SCQ score of children with autism including non-autistic mild or moderate mental retardation.

was 24.2, whereas the general population mean The SCQ authors acknowledge that more data is needed to

was 5.2. determine the frequency of false negatives (Rutter et al.,

The threshold reflecting the need for diagnostic 2003).

assessment is 15. This SCQ is available from Western Psychological Services.

A slightly lower threshold might be appropriate if

other risk factors (e.g., the child being screened

is the sibling of a person with ASD) are present.

Presentation Outline Autistic Disorder Diagnostic Criteria

z Introduction: Reasons for Increased Vigilance A. A total of six (or more) items for (1), (2), and (3), with

at least two from (1), and one each for (2) and (3):

z Diagnostic Classifications and Special (1) qualitative impairment in social interaction, as manifested

Education Eligibility by at least two of the following:

a) marked impairment in the use of multiple nonverbal

z School Psychologist Roles, Responsibilities, behaviors such as eye-to-eye gaze, facial expression, body

postures, and gestures to regulate social interaction

and Limitations b) failure to develop peer relationships appropriate to

developmental level

z Case Finding c) a lack of spontaneous seeking to share enjoyment,

interests, or achievements with other people (e.g., by lack

z Screening and Referral of showing, bringing, or pointing out objects of interest)

z Assessment: Diagnostic and Psycho-educational d) lack of social or emotional reciprocity

Evaluation

Autistic Disorder Diagnostic Criteria Autistic Disorder Diagnostic Criteria

A. A total of six (or more) items for (1), (2), and (3), with A. A total of six (or more) items for (1), (2), and (3), with at

at least two from (1), and one each for (2) and (3): least two from (1), and one each for (2) and (3):

(2) qualitative impairments in communication as manifested (3) restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior,

by at least one of the following: interests, and activities, as manifested by at least one of

a) delay in, or total lack of, the development of spoken the following:

language (not accompanied by an attempt top compensate a) encompassing preoccupation with one or more stereotyped

through alternative modes of communication such as and restricted patterns of interest that is abnormal either in

gesture or mime) intensity or focus

b) in individuals with adequate speech, marked impairment in b) apparently inflexible adherence to specific, nonfunctional

the ability to initiate or sustain a conversation with others routines or rituals

c) stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic c) stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms (e.g., hand or

language finger flapping or twisting, or complex whole-body

d) lack of varied, spontaneous make-believe play or social movements)

imitative play appropriate to developmental level d) persistent preoccupation with parts of objects

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 10

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Autistic Disorder Diagnostic Criteria Other ASDs

B. Delays or abnormal functioning in at least one of the z Aspergers Disorder

following areas, with onset prior to age 3 years: (1) social The criteria for Aspergers Disorder are essentially

interaction, (2) language as used in social communication, the same as Autistic Disorder with the exception that

or (3) symbolic or imaginative play. there are no criteria for a qualitative impairment in

communication.

C. The disturbance is not better accounted for by Retts In fact Aspergers criteria require no clinically

Disorder or Childhood Disintegrative Disorder. significant general delay in language (e.g., single

words used by 2 years, communicative phrases used

by 3 years).

Other ASDs Other ASDs

z Childhood Disintegrative Disorder (CDD) z Retts Disorder

Criteria are essentially the same as Autistic Disorder. z Both Autistic Disorder and Retts Disorder criteria include

Difference include that in CDD there has been delays in language development and social engagement

(a) Apparently normal development for at least the first 2 years after (although social difficulties many not be as pervasive).

birth as manifested by the presence of age-appropriate verbal z Unlike Autistic Disorder, Retts also includes

and nonverbal communication, social relationships, play, and (a) head growth deceleration,

adaptive behavior; and that there is (b) loss of fine motor skill,

(b) Clinically significant loss of previously acquired skills (before age (c) poorly coordinated gross motor skill, and

10 years) in at least two of the following areas: (d) severe psychomotor retardation.

1. expressive or receptive language;

2. social skills or adaptive behavior;

3. bowel or bladder control;

4. play;

5. motor-skills.

Symptom Onset Developmental Course

z Autistic Disorder is before the age of three years. z Autistic Disorder:

Before three years, their must be delays or abnormal Parents may report having been worried about the

functioning in at least one of the following areas: (a) social childs lack of interest in social interaction since or

interaction, (b) social communicative language, and/or (c) shortly after birth.

symbolic or imaginative play.

In a few cases the child initially developed normally

z Aspergers Disorder may be somewhat later. before symptom onset. However, such periods of

z Childhood Disintegrative Disorder is before the age of 10 normal development must not extend past age three.

years. Duration of Autistic Disorder is typically life long, with

Preceded by at least two years of normal development. only a small percentage being able to live and work

z Retts Disorder is before the age of 4 years. independently and about 1/3 being able to achieve a

Although symptoms are usually seen by the second year of partial degree of independence. Even among the

life. highest functioning adults symptoms typically continue

to cause challenges.

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 11

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Developmental Course Associated Features

z Aspergers Disorder:

Motor delays or clumsiness may be some of the first symptoms z Aspergers Disorder is the only ASD not typically associated

noted during the preschool years. with some degree of mental retardation.

Difficulties in social interactions, and symptoms associated with z Autistic Disorder is associated with moderate mental

unique and unusually circumscribed interests, become apparent retardation. Other associated features include:

at school entry. unusual sensory sensitivities

Duration is typically lifelong with difficulties empathizing and abnormal eating or sleeping habits

modulating social interactions displayed in adulthood.

unusual fearfulness of harmless object or lack of fear for real

z Retts and Childhood Disintegrative Disorders: dangers

Lifelong conditions. self-injurious behaviors

Retts pattern of developmental regression is generally z Childhood Disintegrative Disorder is associated with severe

persistent and progressive. Some interest in social interaction mental retardation.

may be noted during later childhood and adolescence.

The loss of skills associated with Childhood Disintegrative

z Retts Disorder is associated with severe to profound mental

Disorder plateau after which some limited improvement may retardation.

occur.

Age Specific Features Gender Related Features

z Chronological age and developmental level

influence the expression of Autistic Disorder.

z With the exception of Retts Disorder,

Thus, assessment must be developmentally sensitive. which occurs only among females, all other

For example, infants may fail to cuddle; show indifference or ASDs appear to be more common among

aversion to affection or physical contact; demonstrate a lack

of eye contact, facial responsiveness, or socially directed males than females.

smiles; and a failure to respond to their parents voices.

On the other hand, among young children, adults may be

The rate is four to five times higher in males

treated as interchangeable or alternatively the child may than in females.

cling to a specific person.

Differential Diagnosis Differential Diagnosis

Retts Disorder z Affects only girls Schizophrenia z Years of normal/near normal

z Head growth deceleration development

z Loss of fine motor skill z Symptoms of hallucinations/delusions

z Awkward gait and trunk movement z Loss of fine motor skill

z Mutations in the MECP2 gene z Awkward gait and trunk movement

Childhood z Regression following at least two years z Mutations in the MECP2 gene

Disintegrative Disorder of normal development Selective Mutism z Normal language in certain situations or

Aspergers Disorder z Expressive/Receptive language not settings

delayed z No restricted patterns of behavior

z Normal intelligence Language Disorder z No severe impairment of social

z Later symptom onset interactions

z No restricted patterns of behavior

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 12

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Differential Diagnosis Developmental and Health History

ADHD z Distractible inattention related to external

(not internal) stimuli

z Prenatal and perinatal risk factors

z Deterioration in attention and vigilance Greater maternal age

over time Maternal infections

Mental Retardation z Relative to developmental level, social z Measles, Mumps, & Rubella

interactions are not severely impaired z Influenza

z No restricted patterns of behavior z Cytomegalovirus

z Herpes, Syphilis, HIV

OCD z Normal language/communication skills

z Normal social skills Drug exposure

Obstetric suboptimality

Reactive Attachment z History of severe neglect and/or abuse

Disorder z Social deficits dramatically remit in

response to environmental change

Developmental and Health History Developmental and Health History

z Postnatal risk factors z Developmental Milestones

Infection Language development

z Case studies have documented sudden onset of ASD z Concerns about a hearing loss

symptoms in older children after herpes encephalitis.

z Infections that can result in secondary hydrocephalus, such as Social development

meningitis, have also been implicated in the etiology of ASD. z Atypical play

z Common viral illnesses in the first 18 months of life (e.g., z Lack of social interest

mumps, chickenpox, fever of unknown origin, and ear infection)

have been associated with ASD. Regression

Chemical exposure?

MMR?

Developmental and Health History Developmental and Health History

z Medical History z Diagnostic History

Vision and hearing ASD is sometimes observed in association other

Chronic ear infections (and tube placement) neurological or general medical conditions.

Immune dysfunction (e.g., frequent infections) z Mental Retardation (up to 80%)

Autoimmune disorders (e.g., thyroid problems, z Epilepsy (3-30%)

arthritis, rashes) May develop in adolescence

Allergy history (e.g., to foods or environmental EEG abnormalities common even in the absence of seizures

triggers) z Genetic Disorders

10-20% of ASD have a neurodevelopmental genetic syndrome

Gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., diarrhea,

z Tuberous Sclerosis (found in 2-4% of children with ASD)

constipation, bloating, abdominal pain)

z Fragile X Syndrome (found in 2-8% of children with ASD)

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 13

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Developmental and Health History Diagnostic Assessments

z Family History z Indirect Assessment

Epilepsy Interviews and Questionnaires/Rating Scales

Mental Retardation z Easy to obtain

Genetic Conditions z Reflect behavior across settings

z Subject to interviewee/rater bias

z Tuberous Sclerosis Complex

z Fragile X Syndrome z Direct Assessment

z Schizophrenia Behavioral Observations

z Anxiety z More difficult to obtain

z Depression z Reflect behavior within limited settings

z Bipolar disorder z Not subject to interviewee/rater bias

Other genetic condition or chromosomal

abnormality

Indirect Assessment: Rating Scales Indirect Assessment: Rating Scales

z The Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS) z The Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS)

Normative group, 1092 children, adolescents, and young adults

Gilliam, J. E. (1995). Gilliam autism rating scale. reported by parent or teacher to be a person with autism.

Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. Age range 3 to 22.

Designed for use by parents, teachers, and professionals

56 items, 4 scales.

Social Interaction, Communication, and Stereotyped Behavior

scales assesses current behavior.

Developmental Disturbances scale assesses maladaptive behavior

history.

Behaviors are rated on a 4-point scale (Never Observed to

Frequently Observed).

Indirect Assessment: Rating Scales Indirect Assessment: Rating Scales

z The Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS) z The Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS)

South, M., Williams, B. J., McMahon, W. M. Owlye, T.,

Yields an Autism Quotient (AQ) Filipek, P. A., Shernoff, E., Corsello, C. C., Lainhart, J. E.,

AQs are classified on an ordinal scale ranging Landa, R., & Ozonoff, S. (2002). Utility of the Gilliam autism

rating scale in research and clinical populations. Journal of

from Very Low to Very High probability of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32, 593-599.

autism. A score of 90 or above specifies that the z Among a sample of 119 children with strict DSM-IV diagnoses

child is probably autistic. of autism, the GARS consistently underestimated the

likelihood that autistic children in this sample would be

classified as having autism.

z The South et al. (2002) sample mean (90.10) was significantly

below the GARS mean (100).

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 14

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Indirect Assessment: Rating Scales Indirect Assessment: Rating Scales

z The Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS) z The Asperger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale

Gilliam, J. E. (2005). Gilliam autism rating scale (ASDS)

(2nd ed.). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Indirect Assessment: Rating Scales Indirect Assessment: Interview

z The Asperger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale (ASDS) z The Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R)

Age range 5-18. Rutter, M., Le Couteur, A., & Lord, C. (2003). Autism

50 yes/no items. diagnostic interview-revised (ADI-R). Los Angeles, CA:

10 to 15 minutes. Western Psychological Services.

Normed on 227 persons with Asperger Syndrome, autism,

learning disabilities, behavior disorders and ADHD.

ASQs are classified on an ordinal scale ranging from Very

Low to Very High probability of autism. A score of 90 or

above specifies that the child is Likely to Very Likely to have

Aspergers Disorder.

Indirect Assessment: Interview Indirect Assessment: Interview

z The Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R)

z The Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R)

The 93 items that comprise this measure takes approximately 90 to

Semi-structured interview 150 minutes to administer.

Designed to elicit the information needed to diagnose Solid psychometric properties.

autism. z Works very well for differentiation of ASD from nonautistic

Primary focus is on the three core domains of autism (i.e., developmental disorders in clinically referred groups, provided that the

language/communication; reciprocal social interactions; and mental age is above 2 years.

restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped behaviors and z False positives very rare,

interests). z Reported to work well for the identification of Aspergers Disorder.

Requires a trained interviewer and caregiver familiar with However, it may not do so as well among children under 4 years

both the developmental history and the current behavior of of age.

the child. According to Klinger and Renner (2000): The diagnostic interview

The individual being assessed must have a developmental that yields the most reliable and valid diagnosis of autism is the

level of at least two years. ADIR (p. 481).

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 15

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Direct Assessments: ADOS Direct Assessments: ADOS

z The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule z A standardized, semi-structured, interactive play

(ADOS) assessment of social behavior.

Uses planned social occasions to facilitate observation of the

Lord, C., Rutter, M., Di Lavore, P. C., & Risis, S. (). Austims social, communication, and play or imaginative use of material

diagnostic observation schedule. Los Angeles, CA: Western behaviors related to the diagnosis of ASD.

Psychological Services.

z Consists of four modules.

Module 1 for individuals who are preverbal or who speak in

single words.

Module 2 for those who speak in phrases.

Module 3 for children and adolescents with fluent speech.

Module 4 for adolescents and adults with fluent speech.

Direct Assessments: ADOS Direct Assessments: CARS

z Administration requires 30 to 45 minutes. z The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS)

z Because its primary goal is accurate diagnosis, the Schopler, E., Reichler, R., & Rochen-Renner, G.

authors suggest that it may not be a good measure of

(1988). The Childhood Autism Rating Scale

treatment effectiveness or developmental growth

(especially in the later modules). (CARS). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological

Services.

z Psychometric data indicates substantial interrater and

test-retest reliability for individual items, and excellent

interrater reliability within domains and internal

consistency.

z Mean test scores were found to consistently

differentiate ASD and non-ASD groups.

Direct Assessments: CARS Direct Assessments: CARS

z 15-item structured observation tool. z Data can also be obtained from parent interviews and student

z Items scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (normal) to 4 record reviews.

(severely abnormal). z When initially developed it attempted to include diagnostic

z In making these ratings the evaluator is asked to compare the criteria from a variety of classification systems and it offers no

child being assessed to others of the same developmental level. weighting of the 15 scales.

Thus, an understanding of developmental expectations for the 15 z This may have created some problems for its current use

CARS items is essential. z Currently includes items that are no longer considered essential

z The sum ratings is used to determine a total score and the for the diagnosis of autism (e.g., taste, smell, and touch

severity of autistic behaviors response) and may imply to some users of this tool that they are

Non-autistic, 15 to 29 essential to diagnosis (when in fact they are not).

Mildly-moderately autistic 30-37 z Psychometrically, the CARS has been described as

Severely autistic, 37 acceptable, good, and as a well-constructed rating scale.

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 16

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Psycho-educational Assessment Testing Accommodations

z Purposes z The core deficits of autism can significantly impact

test performance.

Develop goals and objectives (which are similar Impairments in communication may make it difficult to

to those developed for other children with special respond to verbal test items and/or generate difficulty

needs). understanding the directions that accompany nonverbal

tests.

z To make progress in social and cognitive proficiencies,

verbal and nonverbal communication abilities, and Impairments in social relations may result in difficulty

adaptive skills. establishing the necessary joint attention.

z To minimize behavioral problems. z Examiners must constantly assess the degree to

which tests being used reflect symptoms of autism

To generalize competencies across multiple

and not the specific targeted abilities (e.g.,

environments. intelligence, achievement, psychological processes).

Testing Accommodations Testing Accommodations

z It is important to acknowledge that the autistic z Prepare the student for the testing experience.

population is very heterogeneous. z Place the testing session in the students daily

z There is no one set of accommodations that will schedule.

work for every student with autism.

z It is important to consider each student as an

individual and to select specific accommodations to

meet specific individual student needs.

Pictures from Stephanie Soloman

Testing Accommodations Testing Accommodations

z Minimize distractions. z Make use of powerful external rewards.

z Make use of pre-established physical structures and z Carefully pre-select task difficulty.

work systems. z Modify test administration and allow nonstandard

responses.

One-on-one work area Sample work systems

Pictures from Stephanie Soloman

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 17

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Testing Accommodations Behavioral Observations

z Carefully pre-select task difficulty. z Students with ASD are a very heterogeneous group,

z Modify test administration and allow nonstandard and in addition to the core features of ASD, it is not

responses. unusual for them to display a range of behavioral

symptoms including hyperactivity short attention span

impulsivity, aggressiveness, self-injurious behavior,

and (particularly in young children) temper tantrums.

z Observation of the student with ASD in typical

environments will also facilitate the evaluation of test

taking behavior.

z Observation of test taking behavior may also help to

document the core features of autism.

Choice of Assessment Instruments Cognitive Functioning

z Childs level of verbal abilities. z Assessment of cognitive function is essential given that,

z Ability to respond to complex instructions and social with the exception of Aspergers Disorder, a significant

expectations. percentage (as high as 80 percent) of students with

z Ability to work rapidly. ASD will also be mentally retarded.

z Ability to cope with transitions during test activities. z Severity of mental retardation can also provide some

guidance regarding differential diagnosis among ASDs.

z IQ is associated with adaptive functioning, the ability to

z In general, children with autism will often perform learn and acquire new skills, and long-term prognosis.

best when assessed with tests that require less social Thus, level of cognitive functioning has implications for determining

engagement and verbal mediation. how restrictive the educational environment will need to be.

Cognitive Functioning Cognitive Functioning

z A powerful predictor of ASD symptom severity. z Regardless of the overall level of cognitive functioning,

z However, given that children with ASD are ideally first it is not unusual for the student being tested to display

evaluated when they are very young, it is important to an uneven profile of cognitive abilities.

acknowledge that it is not until age 5 that childhood IQ z Thus, rather that simply providing an overall global

correlates highly with adult IQ. intelligence test score, it is essential to identify these

Thus, it is important to treat the IQ scores of the very young cognitive strengths and weaknesses.

child with caution when offering a prognosis, and when making z At the same time, however, it is important to avoid the

placement and program planning decisions.

temptation to generalize from isolated or splinter skills

However, for school aged children it is clear that the

appropriate IQ test is an excellent predictor of a students when forming an overall impression of cognitive

later adjustment and functioning in real life (Frith, 1989, p. 84). functioning, given that such skills may significantly

overestimate typical abilities.

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 18

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Cognitive Functioning Cognitive Functioning

z Selection of specific tests is important to z On the other hand, for students who have more

obtaining a valid assessment of cognitive severe language delays measures that

functioning (and not the challenges that are

minimize verbal demands are recommended

characteristic of ASD).

(e.g., the Leiter International Performance

z The Wechsler and Stanford-Binet scales are

Scale Revised, Raven Coloured Progressive

appropriate for the individual with spoken

language. Matrices)

Functional/Adaptive Behavior Functional/Adaptive Behavior

z Given that diagnosing mental retardation requires examination z Profiles of students with ASD are unique.

of both IQ and adaptive behavior, it is also important to Individuals with only mental retardation typically display flat

administer measures of adaptive behavior when assessing profiles across adaptive behavior domains

students with ASD.

Students with ASD might be expected to display relative

z Other uses of adaptive behavior scales when assessing strengths in daily living skills, relative weaknesses in

students with ASD are: socialization skills, and intermediate scores on measures of

a) Obtain measure of childs typical functioning in familiar communication abilities.

environments, e.g. home and/or school.

b) Target areas for skills acquisition. z To facilitate the use of the Vineland Adaptive

c) Identifying strengths and weaknesses for educational planning Behavior Scales in the assessment of individuals

and intervention with ASD, Carter et al. (1998) have provided special

d) Documenting intervention efficacy norms for groups of individuals with autism

e) Monitoring progress over time.

Functional/Adaptive Behavior Social Functioning

z Tools that provide an overview of social functioning (i.e.,

z Other tools with subtests for assessing social needs and current repertoire)

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales.

functional/adaptive behaviors:

Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised.

Brigance Inventory of Early Development. z Typical problem areas/issues:

Early Learning Accomplishment Profiles. Understanding facial expressions and gestures

Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised. Knowing how and when to use turn-taking skills, including

focusing on the interest of others

AAMD Adaptive Behavior Scale. Interpreting non-literal language such as idioms and metaphors

Learning Accomplishments Profile. Recognizing that others intentions do not always match their

verbalizations

Developmental Play Assessment Instrument.

Understanding the hidden curriculum those complex social rules

that often are not directly taught (Myles & Simpson, 2001, p. 6)

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 19

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Language Functioning (AACAP, 1999) Language Functioning

z Measures of single word vocabulary z Specific Tests (Myles & Adreon, 2001)

(receptive and expressive). Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals

z Actual use of language (receptive and Third Edition

expressive). Comprehensive Receptive and Expressive

Vocabulary Test

z Articulation and Oral-Motor skills as indicated

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test Third Edition

z Pragmatic Skills ( the childs capacities for Test of Language Competence Expanded

use of whatever level of communication skills Edition (Level 2)

he/she has in relation to the social context). Test of Pragmatic Language

Test of Problem Solving - Adolescent

Psychological Processes Academic/Developmental Assessment

z Helps to further identify learning strengths and weakness. z Assessment of academic functioning will often reveal a profile of

strengths and weaknesses.

z Depending upon age and developmental level, traditional

measures of such processes may be appropriate. It is not unusual for students with ASD be hyperverbal/hyperlexic,

while at the same time having poor comprehension and difficulties

z It would not be surprising to find relatively strong rote, mechanical, with abstract language. For others, calculation skills may be well

and visual-spatial processes; and deficient higher-order conceptual developed, while mathematical concepts are delayed.

processes, such as abstract reasoning. z For students functioning at or below the preschool range and with

z While IQ test profiles should never be used for diagnostic a chronological age of 6 months to 7 years, the

purposes, it would not be surprising to find the student with Autistic Psychoeducational Profile Third Edition may be an appropriate

Disorder to perform better on non-verbal (visual/spatial) tasks than choice.

tasks that require verbal comprehension and expression. z For students who are very severely cognitively delayed, the

The student with Aspergers Disorder may display the exact opposite Adolescent and Adult Psychoeducational Profile (AAPEP) may be

profile. an appropriate choice.

Academic/Developmental Assessment Academic/Developmental Assessment

z For older, higher functioning students, the Woodcock-Johnson z Curriculum-based assessment

Tests of Achievement and the Wechsler Individual Achievement Reading decoding (often a strength) should be compared to

Test would be appropriate tools. comprehension (often a weakness).

Comprehension may be related to

z Subject matter

z Instructional setting (large group vs. individual work)

z Stress level

Written language skills to be assessed

z Organization and coherence

z Provision of sufficient background

z Creativity

Computer generated writing samples should be compared to

handwritten samples (fine motor often weak).

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 20

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Emotional Functioning Emotional Functioning

z 65% present with symptoms of an additional z There are occasional reports of schizophrenia developing in

psychiatric disorder such as AD/HD, oppositional adolescence.

defiant disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder and z Given these possibilities, it will also be important for the school

other anxiety disorders, tics disorders, affective psychologist to evaluate the students emotional/behavioral status.

disorders, and psychotic disorders. z Traditional measures such as the Behavioral Assessment System

z AH/HD is the most common comorbid diagnosis for Children would be appropriate as a general purpose screening

among adolescents and adults. tool, while more specific measures such as The Childrens

Depression Inventory and the Revised Childrens Manifest Anxiety

z Disorders of mood (both depression and mania) are Scale would be appropriate for assessing more specific presenting

the second most common co-existing diagnosis and concerns.

are seen particularly in higher-functioning individuals

among individuals latency age and beyond.

16.9% of CBCL (parent) ratings have elevated depression

subscales.

Emotional Functioning Sensory Assessments

When to consider comorbidity in ASD (Hendren, 2003, p. 39) z Occupational Therapy Assessments

1. When signs of problems outside the autism spectrum Particularly if there is some degree of sensory

are apparent. hyper or hyposensitivity or difficulties in motor

2. When there is an abrupt change in behavior from development.

baseline. z The Sensory Profile (Dunn, 1999)

3. When there is a severe and incapacitating problem z Short Sensory Profile (McIntosh et al., 1999)

behavior. z Sensory Integration Inventory Revised (Reisman &

4. When there is a worsening of symptoms already Hanschu, 1992)

present

5. When student does not respond as expected to

intervention.

Special Education Report

Functional Behavioral Assessment Recommendations

z Identify and describe target behavior z Target specific areas of need and strive to

z Describe establishing operations and immediate build upon learning assets.

antecedents z Sample recommendations

z Collect baseline data/work samples

z Determine the function of the behavior

z Develop a behavior intervention plan

z Assessment tools

z http://www.csus.edu/indiv/b/brocks/Courses/EDS%20240/student_materials.htm

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 21

Identifying, Screening, and Assessing Autism at School NASP & AHD Summer Conference

July 28, 2006

Contact Information

z Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D.

Associate Professor

Department of Special Education, Rehabilitation,

and School Psychology

CSU, Sacramento

916-278-5919

brock@csus.edu

http://www.csus.edu/indiv/b/brocks/

Stephen E. Brock, Ph.D., NCSP 22

También podría gustarte

- Brochure - Adult Sensory ToolkitDocumento2 páginasBrochure - Adult Sensory ToolkitSuperfixenAún no hay calificaciones

- Article - OT For Adults W SPDDocumento5 páginasArticle - OT For Adults W SPDSuperfixenAún no hay calificaciones

- 2: Hand Skills: Occupational Therapy: Children, Young People & Families DepartmentDocumento54 páginas2: Hand Skills: Occupational Therapy: Children, Young People & Families DepartmentSuperfixenAún no hay calificaciones

- Articulos BJOTDocumento1 páginaArticulos BJOTSuperfixenAún no hay calificaciones

- Sensory Curriculum For Individuals On The Autism SpectrumDocumento5 páginasSensory Curriculum For Individuals On The Autism SpectrumSuperfixen100% (1)

- Functional and Life Skills Curriculum PDFDocumento9 páginasFunctional and Life Skills Curriculum PDFSuperfixen100% (1)

- Comprehensive Social Skills Taxonomy: Development and ApplicationDocumento10 páginasComprehensive Social Skills Taxonomy: Development and ApplicationSuperfixenAún no hay calificaciones

- PNAS 2015 Aug 112 (31) 9585-90, Fig. S1Documento1 páginaPNAS 2015 Aug 112 (31) 9585-90, Fig. S1SuperfixenAún no hay calificaciones

- PNAS 2015 Aug 112 (31) 9585-90, Fig. 1Documento1 páginaPNAS 2015 Aug 112 (31) 9585-90, Fig. 1SuperfixenAún no hay calificaciones

- Investigacion en DentistasDocumento3 páginasInvestigacion en DentistasSuperfixenAún no hay calificaciones

- Theories and Theorists: Erik EricksonDocumento1 páginaTheories and Theorists: Erik EricksonSuperfixenAún no hay calificaciones

- PNAS 2015 Aug 112 (31) 9585-90, Fig. 4Documento1 páginaPNAS 2015 Aug 112 (31) 9585-90, Fig. 4SuperfixenAún no hay calificaciones

- PNAS 2015 Aug 112 (31) 9585-90, Fig. S2Documento1 páginaPNAS 2015 Aug 112 (31) 9585-90, Fig. S2SuperfixenAún no hay calificaciones

- Time - How First Nine MonthsDocumento6 páginasTime - How First Nine MonthsSuperfixenAún no hay calificaciones

- State of ClinicalDocumento29 páginasState of ClinicalSuperfixenAún no hay calificaciones

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2104)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- M.K.Jayaraj ReportDocumento176 páginasM.K.Jayaraj ReportMas Thulan100% (5)

- Autism Spectrum Disorder AssessmentDocumento150 páginasAutism Spectrum Disorder Assessmentthinkzen100% (3)

- C A R S - PDF - AutismDocumento1 páginaC A R S - PDF - AutismLaura RodriguezAún no hay calificaciones

- The Elevated SquareDocumento2 páginasThe Elevated SquareFakhriAún no hay calificaciones

- Autism Fact Sheet EnglishDocumento1 páginaAutism Fact Sheet Englishapi-332835661Aún no hay calificaciones

- Andrea Crespo - StimmingDocumento21 páginasAndrea Crespo - Stimmingmanuel arturo abreuAún no hay calificaciones

- CĂRȚI Despre AutismDocumento5 páginasCĂRȚI Despre AutismBancoș Eva100% (1)

- The History of AutismDocumento10 páginasThe History of AutismAleksandra GabrielaAún no hay calificaciones

- Komorbiditas Anak Gangguan Spektrum AutismeDocumento6 páginasKomorbiditas Anak Gangguan Spektrum AutismeIrvan Wahyu PutraAún no hay calificaciones

- Vicky Slonims Distinguishing ASD SLI PDFDocumento16 páginasVicky Slonims Distinguishing ASD SLI PDFsandrmrAún no hay calificaciones

- Presentation For PROPOSALDocumento12 páginasPresentation For PROPOSALNikko MelencionAún no hay calificaciones

- Tony Attwood, Asperger GirlsDocumento2 páginasTony Attwood, Asperger GirlsEla Nata100% (1)

- Aba Therapy For Autistic Children The Benefit of Using ABA Therapy at HomeDocumento2 páginasAba Therapy For Autistic Children The Benefit of Using ABA Therapy at HomeCristina MogosAún no hay calificaciones

- Research in Autism Spectrum DisordersDocumento7 páginasResearch in Autism Spectrum DisordersPriscila FreitasAún no hay calificaciones

- Autism Spectrum DisorderDocumento27 páginasAutism Spectrum DisorderFrenstan Tan100% (2)

- Autism AspergerDocumento24 páginasAutism AspergerusavelAún no hay calificaciones

- Pending Indent ReportDocumento64 páginasPending Indent ReportANIL SINGHAún no hay calificaciones

- Autism Spectrum Disorders The Role of Genetics in Diagnosis and TreatmentDocumento210 páginasAutism Spectrum Disorders The Role of Genetics in Diagnosis and TreatmentBryan Kaufman100% (1)

- مصادر المشكلات النفسية الاجتماعية لدى أسر الأطفال التوحديين من وجهة نظر الأمهاتDocumento19 páginasمصادر المشكلات النفسية الاجتماعية لدى أسر الأطفال التوحديين من وجهة نظر الأمهاتManar BIADAún no hay calificaciones

- References Assignment 2 Spe3002Documento2 páginasReferences Assignment 2 Spe3002api-238596576Aún no hay calificaciones

- Designing Affective Video Games To Support The Social-Emotional Development of Teenagers With Autism Spectrum DisordersDocumento3 páginasDesigning Affective Video Games To Support The Social-Emotional Development of Teenagers With Autism Spectrum DisordersMitu Khandaker-KokorisAún no hay calificaciones

- School For Autism-SynopsisDocumento23 páginasSchool For Autism-Synopsisvaishus93Aún no hay calificaciones

- AdosDocumento11 páginasAdoseducacionchileAún no hay calificaciones

- Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Hsu-Min Chiang, Immanuel WinemanDocumento13 páginasResearch in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Hsu-Min Chiang, Immanuel WinemaneaguirredAún no hay calificaciones

- Autism SpectrumDocumento4 páginasAutism Spectrumapi-165286810Aún no hay calificaciones

- Autismo e Hiperlexia: J. Martos-Pérez, R. Ayuda-PascualDocumento4 páginasAutismo e Hiperlexia: J. Martos-Pérez, R. Ayuda-PascualTom HernandezAún no hay calificaciones

- The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ) - Adolescent VersionDocumento8 páginasThe Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ) - Adolescent VersionMaria Clara RonquiAún no hay calificaciones

- Making Art AutismDocumento6 páginasMaking Art Autismapi-280252266Aún no hay calificaciones

- Fact Sheet Asperger SyndromeDocumento6 páginasFact Sheet Asperger SyndromeAnonymous Pj6OdjAún no hay calificaciones

- Table 2 ASD Specific ScreeningDocumento7 páginasTable 2 ASD Specific ScreeningJovanka SolmosanAún no hay calificaciones