Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Caasi-Lit, Merdelyn T., and Dulce Blanca T. Punzalan

Cargado por

Deo DoktorDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Caasi-Lit, Merdelyn T., and Dulce Blanca T. Punzalan

Cargado por

Deo DoktorCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

10th

World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

Bamboo Shoots as Food Sources in the Philippines: Status and

Constraints in Production and Utilization

Merdelyn T. Caasi-Lit1 and Dulce Blanca T. Punzalan2

1

Institute of Plant Breeding, Crop Science Cluster, College of Agriculture, University of the Philippines,

Los Baos (UPLB), 4031 College, Laguna, Philippines; binglit610429@gmail.com.

2

President & COO / Director, Filbamboo Exponents Inc. and Executive Director/Proprietor, Crea 8 Innov

8 Marketing; dulzbtp@yahoo.com

Abstract

Bamboo biodiversity and conservation in these times of natural and man-made disasters and

calamities is very important. The dwindling number of bamboo species in the forests and natural

waterways is already unabated. This is coupled with increasing human population that not only continues

to contribute to pollution of the environment, but also extract resources, thus natural bamboo groves are

disappearing. Because of this, use of bamboo shoots as food source is limited especially where there are

no more bamboo stands. This is also the result of its status as a poor mans timber and a minor forest and

natural resource in the past decades. This paper generally aims to disseminate the back to basics

importance of bamboo and bamboo shoots, campaign for its continued planting and advocate for better

appreciation of its use as food especially to a generation that has been alienated from traditional food

items. Genetic conservation for this crop species is being promoted not only for food and wellness but

also for its vital role in the environment. It specifically presents the status and prospect of bamboo shoots

as potential food source in the Philippines. Some unpublished data and observations on shoot

characteristics and plantation establishment of some local bamboo species are also presented as well as

the economic benefits of bamboo shoot farming based on previous studies. Problems in bamboo shoot

R&D, constraints in production and utilization are also enumerated. The paper also encouraged the

continuous and reinvigorated use of bamboo shoots as food source in the Philippines. The current

prospects of bamboo initiatives are also discussed. With the above aims, bamboo will be the renewable

resource in this most vulnerable time of climate change.

Introduction

Bamboo, with its thousand uses, is now becoming more popular in the Philippines especially for

multiple benefits for humans and the environment. Popularly known before as the poor mans timber,

it is now hailed as the climate change grass and retaining its famous descriptive line the tallest grass of

life. Stands of bamboos are everywhere in the country, the Philippines being endowed with many native

(including endemic) bamboo species that are naturally growing in different habitats. Several species have

also been introduced and are now acclimated or well adapted to local conditions.

However, the natural stands of bamboo have dwindled and so have the bamboo shoots. With the

onslaught of natural and man-made calamities especially soil erosion and flooding, the acreage of bamboo

had significantly decreased in the whole archipelago in the last centuries. As a consequence, bamboo

shoots for food has also decreased. Recent findings also showed that this underutilized food source is also

unpopular to the new generation of Filipinos, who have been more accustomed to Western cuisine, often

less healthy, fast food style. With this scenario, there is a great challenge to educate our young people to

patronize the use of bamboo shoot as food.

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

Bamboo shoots from all bamboo species can be used as vegetable shoots. From the shoots of the

giant bamboo (Dendrocalamus asper) which can feed the whole of the barrio folks to the thin shoots of

anos (Schizostachyum lima) which is asparagus-like and can be used as ingredients for any delicacy.

Popularly known as labong in Southern Tagalog and the Bicol region, rabung in the Ilocandia and

northern regions, dabung in Cebu and mostly in the Visayas and Mindanao provinces. or tambo in

Iloilo and other regions, and many other names by indigenous people (hubwal, harepeng, uvug, etc.) are

evidence that bamboo shoots are widely used as food for most Filipinos. Dinengdeng, lumpia,

paklay, ginataan, adobo, atsara, kilawen, chopsuey, and many more commonly cooked

recipes can have bamboo shoots as the main ingredients (Caasi-Lit 1999).

As the tree of life, the longest and fastest growing grass species, an emblem of longevity,

resilience and endurance, bamboo shoots are highly valued as food in China and Japan and other Asian

countries. Bamboo shoots are very nutritious, an organic, renewable and sustainable resource, the health

food of the modern century. Researches on bamboo shoots and reviews were also conducted specifically

on the survey of bamboo shoot resources in the Philippines and the cyanide content of several bamboo

species with quality shoots (Caasi-Lit et al. 2010a; Caasi-Lit et al. 2010b). References for the basic aspect

of the bamboo shoot are those of Santos (1986), Dransfield and Widjaja (1995), Rojo et al. (2000) and

Virtucio & Roxas (2003).

However, only few studies have been done for bamboo shoot research and development (R&D)

under Philippine conditions. Most of the work focused on culm propagation, production, harvesting and

marketing. As such, with the lack of basic information on shoot characteristics, it will be difficult to

formulate a business venture on bamboo shoot production. The lack of funds for basic research on

bamboo shoots is also a major reason for the lack of baseline information.

With the recent awareness of the importance of the environment, bamboo is now an emerging and

very promising commodity. This is demonstrated by the banner program of the government for bamboo

reforestation targeting 500,000 hectares as its contribution to ASEAN commitment of 20 million hectares

of new forest by 2020. Bamboo can be the anchor renewable resource that can be tapped for commercial

production, community livelihood and environmental protection initiatives.

This paper aims to: 1) assess the status and prospects of bamboo shoots as potential food source

or as vegetable in the Philippines; 2) enumerate the problems in bamboo shoot R&D and constraints in

production and utilization; 3) present some unpublished data and observations on shoot characteristics

and plantation establishment of some local bamboo species; and 4) document the economic benefits of

bamboo shoot farming based on previous studies and promote the continuous use of bamboo shoots as

food source in the Philippines.

Status of Bamboo Shoots as Food

In the Philippines, bamboo shoots are underutilized as food sources. The supply remains very

limited especially during the dry season. In a survey conducted in late 1990s, there was a lack of

information on the importance of bamboo shoots as food especially among the young generation and on

the aspect of bamboo shoot research and development (Caasi-Lit 1999, 2000). Deforestation and land

conversion had limited the supply of bamboo shoots in the local market. However, due to increasing

human population that not only continues to contribute to pollution of the environment, but also extract

resources, the natural bamboo groves are disappearing. Flooding, landslides and other natural calamities

also contributed to the limited supply of bamboo shoots.

An estimate by the Bureau of Agricultural Statistics in 2002-2007 showed an annual average of

7,722 ha of bamboo was harvested for bamboo shoots (BAS 2007). Supply of bamboo shoots in the local

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

market in different provinces are mostly from fresh whole bamboo shoot, sliced fresh shoots, and cooked

sliced shoots. Canned bamboo shoots from China and Japan are available in the supermarkets and most

food stores in the business district of Divisoria, Metro Manila. As of this writing, all bamboo shoots are

manually processed and there is no available factory for bamboo shoot processing. Canned bamboo

shoots and other bamboo shoot products are mostly traded from China.

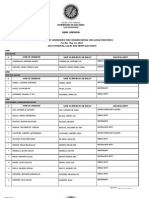

Bamboo Species Commonly Used as Food Source

As mentioned in our previous studies, all bamboo species can be used as food as long as the

cyanide content is removed or diminished. In the Philippines, the most common species of bamboo for

food are enumerated by Batugal (1975), Caasi-Lit (1999); Virtucio and Roxas (2003), Caasi-Lit et al.

(2010). The most common species listed in Table 1 are the spiny bamboo or Kawayang tinik or

(Bambusa blumeana), Bayog (Bambusa merrilliana), Laak (Bambusa philippinensis), Common bamboo

or Kiling (Bambusa vulgaris var. vulgaris), Giant bamboo (Dendrocalamus asper), Machiku

(Dendrocalamus latiflorus), Kayali (Gigantochloa atter), Bolo (Gigantochloa levis). Bayog and Laak

are the two endemic species in the country. Bayog is found in almost all parts of the country with the

original samples taken from Palo, Leyte. Laak is abundant in Mindanao and was originally found only in

Mati, Davao Oriental. Based on the survey in 1999-2000, the most predominant local bamboo species in

different parts of the country was B. blumeana followed by B. vulgaris.

Comparison of Young Shoots

Only the young shoots of seven local species (B. merrilliana and B. philippinensis) are

qualitatively described below (Fig. 1-7). A preliminary study on the detailed morphological

characteristics of young shoots of some local bamboo species for identification is presented in a separate

paper by Ricohermoso et al. (2014).

B. blumeana (Fig. 1a & b). The shoots are light grayish green and smooth with few trichomes on

leaf sheaths. The blades are appressed from base to tip.

B. merrilliana (Fig. 1c & d). Almost similar to B. blumeana except for the blade posture being

appressed at the base and middle and reflexed toward the tip.

B. philippinensis (Fig. 2a & b). Young shoots are light green and largely covered with thick black

trichomes. The blades are enlarged from the neck especially extending the whole structure at the tip of the

shoots

G. atter (Fig. 2c & d). Young shoots are light orange brown and covered with thick light grayish

trichomes (tufted). The blades are relatively extended and reflexed and get enlarged at the apex of the

shoots.

G. levis (Fig. 3a & b). Young shoots are brick brown and almost similar to G. atter except that the

culm sheaths are covered with very thick hairs. The blades are extended and reflexed and enlarged

towards the apex.

D. asper (Fig. 3c). The shoots of the giant bamboo are light grayish light brown with dull purple

outline of the culm sheaths. The blades generally resemble that of the genera Gigantochloa. The blades

are reflexed from the base to the tip of the shoots.

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

D. latiflorus (Fig. 4a & b). The shoots are light green, smooth with very fine unnoticeable hairs.

The culm sheaths do not have a marked outline like D. asper but with only fine outline and light yellow

patches. The blades are reflexed from the base to the tip.

Exterior and interior sections of the young shoots

Figure 5 shows the external features of fresh whole young shoots (a) and the peeled fresh shoots

(b) of the different local bamboo species. The exterior appearance of bamboo shoots can already serve as

a guide to identify the different species of bamboo. This is through the color of the young shoots, the

nature of the culm sheaths with the distinct blade at the apex. The blade is the most prominent identifying

mark. All of the shoots are generally shaped like a pyramid, stupa, pagoda, cone, bell or polygon and

variation of the sizes at the base middle and tip of the shoot.

Peeled fresh shoots are also shaped like pyramid or pagoda (Fig. 5). The shape of the peeled

shoots of Bambusa are like the dome-shaped top of churches that tapers at the tip. The shoots of

Gigantochloa spp are acutely conical with distinct pointed tip. The shape of the shoots of Dendrocalamus

spp are like the Aztec pyramids in Mexico heavy and solid at the base with the prominent sharp tip.

When cut longitudinally, the interior of the shoots is hollow showing the tapering hollow portion

(internode) and the filled layers or solid plates (nodes) as shown in Fig. 6 and Fig. 7. The interior of most

Bambusa species (Laak and Kiling) have tapering solid layers and thick culms while the Gigantochloa

spp. have two layers, the thin upper layer and the thicker lower layer (Fig. 6). On the other hand, young

shoots of Dendrocalamus spp. have solid and almost without the characteristic hollow at the central

portion of the shoots (Fig. 7).

Fig. 1 (a, b, c & d).

Fig. 2 (a, b, c & d)

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

Fig. 3 (a, b, & c)

Fig 4. (a & b).

Fig. 5 (a & b)

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

Table 1. Commonly used species of locally grown bamboo as food source in the Philippines (modified

from Caasi-Lit 1999).

Scientific name Common name Tagalog/Filipino Other languages

Commonly used

Bambusa blumeana Spiny bamboo Kawayang tinik Siitan (Ilocano); Batakan,

Tunukon (Bisaya); Dugian,

Kabugauan, Marurugi,

Rugian (Bikol)

Bambusa merrilliana None Bayog

Bambusa philippinensis Laak

Bambusa vulgaris Common bamboo Kiling, Taring, Tiling, Limas (Panay);

Tewanak Sinamgang (Cebu); Maribal

(Bikol)

Dendrocalamus asper Giant bamboo Giant bolo Botong (Bikol); Butong

(Bisaya); Patong (Bisaya)

Dendrocalamus latiflorus Machiku Buntong (Cebu); Botong

(Davao)

Gigantochloa atter Kayali

Gigantochloa levis Poring bamboo; Bolo, Kawayan tsina, Bolo, Botong (Panay); Buton

smooth-shoot Bongsina, Buhong- (Cebu); Kabolian, Patong

gigantochloa china (Bikol)

Not commonly used

Cephalostachyum Bagto Bagtok, Bikal (Bikol)

mindorense

Dinochloa luconiae Osiu, Timak, Usiu Bika, Bikal (Ibanag);

Bolokaui (Bisaya); Malilit

(Sambali)

Dinochloa pubiramea Bukao (Yakan)

Schizostachyum lima Anos Bagakai (Bisaya; Bikol);

Sumibiling (Tagbanua); Bitu

(Pampangan); Lakap

(Bukidnon); nao-nap (Cebu)

Schizostachyum lumampao Buho, Lumampao Bagakan (Bisaya)

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

Fig. 6 (a, b, c, & d).

Fig. 7 (a & b).

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

Cyanide content of local bamboo species

The bitter chemical of fresh bamboo shoots is called hydrocyanic acid or cyanide (CN).

Cyanide occurs widely in nature and it is even present in human blood at low concentrations

(Montgomery 1980). Among bamboos as in many other grasses and plants, they are released from

cyanogenic glucosides in plant tissues, which have evolved as mechanisms to counter herbivore attacks.

However, high concentration of cyanide is lethal to humans. Oral lethal dose for humans ranges from 0.5-

3.5 mg/kg body weight (Bradbury and Holloway 1998).

Gonzalez and Apostol in 1968 reported the chemical properties and eating qualities of some local

bamboo species. Their study showed that B. blumeana was most preferred for eating. In the study of

Batugal (1975), the young shoots of some uncommon local bamboo species were also edible such as

Anos, Bagto, Bagakan and Kalbang. In 1995, studies from the Ecosystem Research Development Bureau

of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources listed three bamboo species which were

primarily utilized as shoots namely Bayog (earlier identified as B. blumeana var. luzonensis), Kawayang

tinik (B. blumeana) and Kayali (G. atter).

Percent reduction in cyanide content (ppm) of fresh shoots after boiling for 15 minutes from a

bamboo plantation in Sta.Cruz (Laguna Province) and another in Davao was significant for all bamboo

species (Caasi-Lit et al. 2010). The highest cyanide content in fresh samples was observed in B. vulgaris

followed by B. philippinensis while the lowest was observed on D. latiflorus. Comparison of the cyanide

content (pooled means from the two sites) among the three genera of common bamboos in the Philippines

showed that Bambusa had the highest content followed by Gigantochloa and the least on Dendrocalamus.

Plantation Establishment for Bamboo Shoot Production

As of this date, no large bamboo plantations have been established for bamboo shoot production

in the Philippines except for small scale production from existing plantations originally intended for

banana propping pole production. The following observations and data on bamboo plantation

establishment for shoot production were derived from two field studies conducted in Tagum, Davao and

Sta. Cruz, Laguna (Caasi and Caasi-Lit 1999).

Common Practices and Cultural Management

Depending on the bamboo species that will be used, mulching is recommended several months

after the clumps are ready for harvesting. Machiku (D. latiflorus), a fast growing species as reported by

Pao-cahng Kuo (1978) was observed to produce shoots after two years under Philippine conditions

especially in Davao Province. This area has a Philippine Type IV weather where it rains for almost ten

months giving enough moisture for shoot development. In Laguna and Davao conditions, Gigantochloa

species can be harvested after three years (Caasi-Lit et al., 1999).

The regular cultivation in between clumps and around the bamboo grove can initially improve the

soil and eventually loosen the soil for better shoot production. Very old clumps that have not produced

any shoots during the first year are removed. Cleared spaces allow underground shoots to emerge. Cutting

the top shoot of the bamboo clump can induce shooting.

Important Notes Relevant to the Establishment of Bamboo Shoot Farm

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

Rhizomes versus Cuttings

Depending on the kind of planting propagules to be used, Table 2 compares the production of shoots

using the rhizomes and cuttings as the mother plant. Using rhizomes, shoots can be harvested already even

after only two years of establishment; using cuttings, shoots can be harvested only on the third year.

Generally, planting matured rhizomes can generate more shoots after a year because they contain several

growing points or shoots located at the base of the stump. The major disadvantage of using rhizomes is the

difficulty in harvesting the stump and this demands higher price. If cuttings are considered for the operation

during the first year, it is also feasible to do the propagation activities in the Bamboo Nursery during the first

six months. This will lessen the cost of production in the establishment of the bamboo shoot plantation.

However, the only disadvantage of using bamboo cuttings for planting is the longer time (at least three years)

to produce quality shoots. Since this figure is based on natural rainfall (6 months rain and 6 months dry), the

number of shoots produced will be different if drip irrigation will be available the whole year round.

Table 2. Estimated number of shoots (average) produced using rhizomes and culm/branch cuttings

(Laguna/Davao conditions).

Type of planting materials Year 1 Year 2 Year 3

Rhizomes 6 18 40

Cuttings 3 12 30

Shoot production

Based on previous observations by Caasi & Caasi-Lit (1999) and Caasi (2012) in the different

bamboo plantations in Laguna and Davao, the estimated number of shoots produced by several species of

bamboo is shown in Table 3. Virtucio et al. (1994) reported the actual shoots produced by the endemic

species Laak at 35 shoots on the third year.

Table 3. Estimated number of shoots (average) produced by several bamboo species (Laguna/Davao

conditions).

Bamboo species Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Reference

Tinik 4 8-10 25 Caasi & Caasi-Lit, 1999;

Caasi, 2012 PC

Laak 5-7 18-20 50 Caasi & Caasi-Lit 1999;

Caasi, 2012 PC

Laak 5-7 18 35 44 Virtucio et al. 1991

Kayali 5-7 20-24 50 Caasi & Caasi-Lit 1999;

Caasi, 2012 PC

Bolo 5-7 18 35 Caasi & Caasi-Lit 1999;

Caasi, 2012 PC

Giant 5 8-10 25 Caasi & Caasi-Lit 1999;

Caasi, 2012 PC

Machiku 5-7 20-24 50 Caasi & Caasi-Lit 1999;

Caasi, 2012 PC

PC - Personal Communication

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

Cost Benefit Analysis in Bamboo Shoot Farming

Table 4 shows the cost of propagating 10,000 pieces one-node bamboo culm/branch cuttings using

the Caasi Method of bamboo propagation (Incubation Method). With this method, a single plant propagule or

cutting will cost Php34.80. The cost of establishing a hectare of bamboo shoot farm using the different

bamboo species is shown in Table 5. Based on previous research done in Laguna Province (Caasi & Caasi-Lit

1999), the return on investment for the production of bamboo shoots after three years using different bamboo

species is shown on Table 6. The number of shoots produced after three years is also indicated as this gives an

estimate of the total shoot production. More shoots in the succeeding years will come out as the bamboo plant

matures especially when irrigation and plant maintenance are properly performed. Based on our estimate, it is

therefore practical to engage the three species (Giant bamboo, Machiku and Kayali) into bamboo shoot

production for greater profit.

Table 4. COST AND RETURN ANALYSIS for propagating one-node bamboo culm/branch cuttings using

the Caasi method of bamboo propagation.

PROCESSES AMOUNT IN DAY

PHILIPPINE PESO

A.Acquisition of Materials

1. Cuttings 10,000 pcs x P5/cutting 50,000 1

2. Transport 15,000

3. Treatment (Fungicide) x 2 packs + labor 2,400

Sub-total 67,400

B.Incubation site

1. Materials for shed (bamboo nursery,optional) (35,000) 1-5

2. Labor for incubation site (4 mp x 5 da x 250/da) 5,000

3. Drums (for soaking) 15,000

Sub-total 55,000

C. Incubation process

1. Labor for planting (5 mp x 5 da x 250/da) 6,250 6-21

2. Treatment (4kgs fungicide x 800/kg) 3,200

(4 bottles Growth Enhancer x 400) 1,600

3. Water bill (for 10 cu. m x 15 days x 40/cu. m) 6,000

4. Insecticide (1bottle x 1200) 1,200

5. Labor for watering for 15 days

(1 mp x 15 da x 250) 3,750

Sub-total 22,000

D.Bagging/transplanting

1. Soil mix = 1 part soil: 1 part coir dust

(1liter/bag) (1cu. m : 100 bags) 22-30

(10,000 planting = 10 cu.m x 500) 5,000

(coir dust = 10 cu.m x 400) 4,000

2. Labor for soil mix and planting

(10,000 pcs x 4/bag) 40,000

3. Plastic bags 6x8 (10,000 x 3/bag) 30,000

4. Punching plastic bag (3 md x 250) 750

5. Puncher (3 units x 500/unit) 1,500

Sub-total 81,250

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

E. Maintenance

1. Insecticide/Fungicide (every 7 days, 6 x)

2 bots Plant Enhancer x 400) = 800 x 6 = 4,800 4,800 31-70

1 bot Insecticide x 1,200 = 1,200 x 6 = 7,200 7,200

1 kg Fungicide x 800 = 800 x 6 = 4,800 16,800

2. Labor for everyday watering

21-60 = 40 days x 2 md x 250 20,000

4. Water requirement

1 cu.m/da x 40 da = 40 cu.m x 100 4,000

Sub-total 52,800

TOTAL EXPENSES 278,450

Less 20% Mortality from different causes

COST PER SEEDLING (MATERIALS & LABOR) 34.80

THROUGHPUT TIME 60-70 DAYS

Table 5. Cost of establishing one-hectare bamboo shoot farm using the different bamboo species (In Peso).

INPUT COSTS

Tinik Laak Kayali Bolo Giant Machiku

Population per Hectare (4x4) 625 625 625 625 625 625

A. Site Preparation

Line brushing/weeding/ 10,000 10,000 10,000 10,000 10,000 10,000

staking/sticking/lay-outing

(Labor: 5mp x 8da x 250/da

B. Digging, basal fertilizer

application, planting, 12,000 12,000 12,000 12,000 12,000 12,000

mulching, watering

C. Cost of Fertilizer (complete) 1,200 1,200 1,200 1,200 1,200 1,200

D. Cost of Planting Materials 1.

(Rhizomes) Tinik, Machiku, 37,500 37,500 50,000 50,000 50,000 37,500

Laak@60; Giant, Kayali,

Bolo @80

D2. Cuttings @34.80 21,750 21,750 21,750 21,750 21,750 21,750

E. Cost of Hauling to planting

site 20,000 20,000 20,000 20,000 20,000 20,000

Truck+Barge (approximate

only)

F. Maintenance

Labor (after 2nd, 6th and 12th 40,500 40,500 40,500 40,500 40,500 40,500

month)1

(After planting ring weeding,

cultivating, fertilizing, return 12,000 12,000 12,000 12,000 12,000 12,000

mulch, and other operations)

Replanting of dead plants

(=5% mortality)2 2,812.50 2,812.50 3,437.50 3,437.50 3,437.50 2,812.50

Clearing/Rejuvenating of

clumps after 12 months3 4,500 4,500 4,500 4,500 4,500 4,500

G. Supervision, technical fee and

other miscellaneous expenses 78,000 78,000 78,000 78,000 78,000 78,000

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

Total Cost Per Hectare Using 218,512.50 218,512.50 231,637.50 231,637.50 231,637.50 218,512.50

Rhizomes

Total Cost Per Hectare Using 202,762.50 202,762.50 207,887.50 207,887.50 207,887.50 202,762.50

Cuttings

1

Labor cost is computed at the rate of PHP250/day

2

Computation to get cost and replanting: 5% of 625 = 31.25 x 60 & 80 (cost of rhizome) + Labor [(PHP30@

x 31.25) = PHP 937.50]; For Rhizome=[2,812.50 @ 60 and 3,437.50 @80]; For Cuttings= 34.80 per cuttings.

3

Clearing/Rejuvenating means the removal of small and old dry culms to allow faster development of

more shoot.

Table 6. Return on investment for production of bamboo shoots in one hectare after

three years for several species of Philippine bamboos (Laguna/Davao conditions).

ITEMS TINIK LAAK KAYALI BOLO GIANT MCKU

Population density per hectare

(4x4) 625 625 625 625 625 625

Estimated number of shoots

per clump after 3 years* 25 50 50 40 40 50

Total shoots produced 15,625 31,250 31,250 25,000 25,000 31,250

Mortality rate 20% 20% 20% 20% 20% 20%

Number of mortality 3,125 6,250 6,250 5,000 5,000 6,250

Number of survival 12,500 25,000 25,000 20,000 20,000 25,000

Approximate

Weight of peeled shoots 0.8 0.45 0.8 0.8 1.5 0.8

(Average of Laguna and

Davao conditions)

Total kilos 10,000 11,250 20,000 16,000 30,000 20,000

Estimated Market Price per

kilo of bamboo shoots

(only the least estimate,

possible to be different among 50 50 50 50 50 50

species)

GROSS INCOME 555,000 562,500 1M 800,000 1.5M 1M

Less

Estimated Cost of

218,512.50 218,512.50 231,637.50 231,637.50 231,637.50 218,512.50

investment

(using figures from Table 5)

Less

Estimated Cost of harvest,

transport & other

miscellaneous expenses 180,000 180,000 180,000 180,000 180,000 180,000

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

GROSS INCOME

3rd Year

(Estimate without capital 156,487.50 163,987.50 588,362.50 388,362.50 1.08M 601,487.50

outlay, and all other expenses)

GROSS INCOME

4th year onwards

(does not include the first year 375,000 382,000 820,000 620,000 1.32M 820,000

cost of investment, capital

outlay, etc.

Challenges in Bamboo Shoot R& D

Bamboo shoot production is a very promising venture. However, it is beset with problems and

difficulties especially the insufficient bamboo shoot R & D that will serve as the backbone for appropriate,

locally adapted farming and production technologies.

1. Lack of basic knowledge and information on bamboo shoots, including identification, shelf life

cyanide content, nutritional properties, etc.

2. Difficulty in propagating the species which produce quality shoots such as Dendrocalamus spp,

and Gigantochloa spp.

3. Rampant pilferage of young shoots during the conduct of studies and research implementation.

4. Lack of information on other local bamboo species with potential shoot quality because shoot

production techniques are very specific and species-specific

5. Dearth of information on the R&D on bamboo shoot production

6. Limited knowledge and information on site preparation, cultural management practices, suitable

bamboo species for food, propagation techniques; harvesting and product development, socio-

economics of utilization and marketing

7. Insect pests and diseases of bamboo shoots should be continuously studied especially yield loss

assessment

8. Lesser appreciation on the potential of bamboo shoots as a viable small scale industry for rural

farmers or even larger business ventures

9. Only few researchers are working on R&D of bamboo shoot production which need careful study

and a lot of expertise, practice and experience

10. Lack of funding for basic research on bamboo shoots and low priority by funding agency

Current Prospects in Bamboo Shoot Initiatives

In the Philippines, there is now a growing movement towards innovative, healthy, nutritious and

affordable food enriched with bamboo shoots such as native delicacies, viands, breads, pastries, desserts,

pasta, snacks and beverages. Like-minded individuals, environmental advocates, academe, cooperatives,

private organizations, NGOs and public institutions actively take part in sustainable livelihood and

inclusive growth for poor & marginalized communities through bamboo agri-ecotourism and training of

communities in social entrepreneurship, propagation, plantation management, food safety and quality,

good manufacturing processes, fair trade, processing, production, packaging, marketing and

development of food products made from bamboo combined with indigenous materials. These

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

endeavors are featured online and via multimedia (TV/radio/print), cooking demos, local & international

expos/trade fairs/conferences, arts and cultural events, educational scholarships, feeding programs,

medical missions, healthcare, peacebuilding initiatives, disaster relief/ reduction/risk management and

rehabilitation programs. Some financial institutions have opened credit facilities for community based-

micro and small bamboo enterprises. A draft Philippine Bamboo Industry Roadmap has been submitted

and stakeholders roundtable discussions/consultations are ongoing. There is also a huge potential for

global Halal certified bamboo shoot food & beverages.

Summary and Recommendations

This paper presents the status and prospects of bamboo shoots as potential food source or as

vegetable in the Philippines. Bamboo shoots are undoubtedly one of the nutritious food source available

in the country. There are several local bamboo species with quality vegetable shoots in different regions

with B. blumeana as the predominant species and preferred by most consumers. Bamboo shoot farming

is a potential business venture especially in the rural areas and this can be a source of livelihood for the

rural folks. Some unpublished data and observations based from previous studies in Davao and Laguna

on shoot characteristics and plantation establishment of some local bamboo species are also presented.

Aspects on the economic benefits of bamboo shoot farming using the locally available bamboo species

are shown. Among the bamboo species, Giant bamboo and Machiku are the most profitable for bamboo

shoot farming. Problems in bamboo shoot R&D and constraints in production and utilization are also

enumerated with lack of funding for basic studies on bamboo shoots cited as the major constraint. The

paper also encouraged the continuous use of bamboo shoots as food source in the Philippines and

discussed the current prospects in bamboo shoots initiatives as demonstrated in recent activities among

public, private and academic agencies.

To date, research and development on bamboo shoots as food as well as production of bamboo

shoots for food are very limited. In this light, there is a need to study and strengthen bamboo shoots R &D.

The potential of bamboo shoots as food source is an area that needs a lot of scientific experimentation and

financial support. It is hoped that the government and private companies will consider bamboo shoot

R&D, extension and technology as important vehicle for food security, poverty alleviation, environmental

protection and climate change mitigation. Priorities in the following aspects are recommended:

1. Continue survey of more species with bamboo shoot potential and evaluation of their cyanide

content and nutritive properties

2. Research and development on off-season bamboo shoot production to cater the supply of

bamboo shoots during the dry season

3. More funding and investments for bamboo shoot R&D and capacity building of

community based- bamboo agri-social enterprises in various aspects of the value chain

4. Include bamboo shoot as vegetable crop in agricultural system and disseminate its importance

as food and as a climate change crop.

5. Approval of the upgraded Philippine Bamboo Industry Roadmap.

References

[BAS] Bureau of Agricultural Statistics. 2007. Performance of Philippine Agriculture. Bamboo Shoots

2002-2007. http://www.bas.gov.ph.

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

Batugal, P. 1975. Non-conventional food sources. Depthnews. Permafor Forest and Farms, 8(1), 8.

Bradbury, J.H. and Holloway, W.D. 1998. Chemistry of Tropical Root Crops: Significance for Nutrition

and Agriculture in the Pacific. Australian Center for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR)

Monograph No. 6, 201 p.

Caasi, M.C. and Caasi-Lit, M.T. 1999. Bamboo farming and plantation establishment: learning from two

decades of experience in Davao and Laguna. Paper presented during the 3rd National Bamboo

Conference The Philippines Bamboo Industry in the Next Milennium. June 25-26, 1999,

Cadlan, Pili, Camarines Sur, Philippines. (may be accessed from the file of Dr. Merdelyn T.

Caasi-Lit of the Institute of Plant Breeding, UPLB, College, Laguna).

Caasi-Lit M.T. 1999. Bamboo as Food. In: Bamboo + Coconut [Kawayan + Lubi]. Philippine Coconut

Research and Development Foundation, Inc., Pasig City, 82 p.

Caasi-Lit, M.T. 2000. Bamboo Shoots as Substitute Vegetable During La Nia. Terminal Report. UPLB-

PCARRD Research Funds El Nio R & D Program and the Agricultural Research Management

Division, 72 p.

Caasi-Lit, M.T., Mabesa, L.B. and Candelaria, R.A. 2010. Bamboo shoot resources in the Philippines: I.

Edible shoots and the status of local bamboo shoot industry, Philippine Journal of Crop Science,

35(2), 54-68.

Caasi-Lit, M.T., Mabesa, L.B. and Candelaria, R.A.. 2010. Bamboo shoot resources in the Philippines: II.

Proximate analysis, cyanide content, shoots characteristics and sensory evaluation of local

bamboo species, Philippine Journal of Crop Science, 35(3), 9-18.

Caasi-Lit, M.T., Maghirang, R.G. and Mabesa, L.B. 1999. Potential of bamboo shoots as food for the

new millennium. Paper presented during the 3rd National Bamboo Conference The Philippines

Bamboo Industry in the Next Milennium. June 25-26, 1999, Cadlan, Pili, Camarines Sur,

Philippines. (may be accessed from the file of Dr. Merdelyn T. Caasi-Lit of the Institute of Plant

Breeding, UPLB, College, Laguna).

Dransfield, S.and Widjaja, E.A. (eds). 1995. Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 7. Bamboos,

Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, 189 p.

Gonzales, E.V.and Apostol, I. 1968. Chemical properties and eating qualities of bamboo of different

species. Final Report. Philippine Council for Agriculture and Resources Research. PCARR

Project 283, Study 4, FORPRIDECOM Library, College, Laguna.

Montgomery, R.D. 1980. Cyanogens. In: Toxic Constituents of Plant Foodstuffs. Liener IE (ed)

Academic Press, New York, 143-160.

Pao-chang Kuo. 1978. Machi-ku, a Taiwan bamboo as source of vegetable food. Canopy International,

4(4), 7.

Philippine Bamboo Industry Development Council Technical Working Group (eds.). April 2013.

Philippine Bamboo Congress Conference Proceedings 02 October 2012. World Trade Center

Manila

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

10th World Bamboo Congress, Korea 2015

Ricohermoso, A.L., Caasi-Lit, M.T. and Hadsall, A.S. 2014. Taxonomic study of young shoots of

bamboo species (Subfamily Bambusoideae: Family Poaceae) from the Philippines Unpublished .

BS Thesis. University of the Philippines Los Baos, College, Laguna.

Rojo, J.P., Roxas, C.A., Pitargue, F.C. Jr. and Brias, C.A. 2000. Philippine Erect Bamboos: A Field

Identification Guide. Forest Products Research and Development Institute, Los Baos, Laguna,

Philippines, xii + 162p.

Santos, J.V. 1986. Philippine bamboos. In Guide to Philippine Flora and Fauna. Natural Resources

Management Center and the University of the Philippines. 43 p.

Virtucio, F.D. and Roxas, C.A. 2003. Bamboo Production in the Philippines. Ecosystems Research and

Development Bureau, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, College, Laguna,

202p.

Virtucio, F.D., Manipula, B.M. and Schlegel, F.M. 1994. Culm yield and biomass productivity of Laak

(Sphaerobambos philippinensis). In Proceedings 4th International Bamboo Workshop on Bamboo

in Asia and the Pacific, Chiangmai, Thailand, November 27-30, 1991. FORSPA Publication 6,

IDRC, FAO/UNDP, 95-99 p.

Figure Captions

Figure 1. Shoot characteristics (a) and clump (b) of Bambusa blumeana (Kawayang tinik) and shoot

characteristics (c) and clump (d) of the endemic species, Bambusa merrilliana (Bayog).

Figure 2. Shoot characteristics (a) and clump (b) of the endemic species, Bambusa philippinensis (Laak)

and shoot characteristics (c) and clump (d) of Gigantochloa atter (Kayali).

Figure 3. Shoot characteristics (a) and clump (b) of Gigantochloa levis (Bolo) and shoot characteristics

(a) of Dendrocalamus asper (Giant bamboo).

Figure 4. Shoot characteristics (a) and clump (b) of Dendrocalamus latiflorus (Machiku).

Figure 5. Comparison of the external features of fresh whole young shoots (a)

and peeled fresh shoots (b) of the different local bamboo species.

Figure 6. Longitudinal sections of pagoda-shaped young shoots of Gigantochloa spp. (a. Kayali, b.Bolo)

and Bambusa spp. (c. Laak, d,Kiling) showing the tapering hollow portion (internode) and the filled

layers (nodes).

Figure 7. Longitudinal sections of pagoda-shaped young shoots of Dendrocalamus spp. (Giant bamboo,

Machiku) showing the solid and with very small hollow central portion of the shoots.

Theme: Food and Pharmaceuticals

También podría gustarte

- Socio-Economic Importance of BambooDocumento15 páginasSocio-Economic Importance of BambooAkindele FamurewaAún no hay calificaciones

- Bamboo Research in The Philippines - Cristina ADocumento13 páginasBamboo Research in The Philippines - Cristina Aberigud0% (1)

- Feasibility StudiesDocumento3 páginasFeasibility StudiesKelvin John Sajulan Cabaniero50% (2)

- Guidelines 2.0Documento4 páginasGuidelines 2.0Hansel TayongAún no hay calificaciones

- Philippine National Report On Bamboo and RattanDocumento57 páginasPhilippine National Report On Bamboo and RattanChristine Mae C. Almendral80% (5)

- Spatial Distribution of Buri Mother Plant (Corypha Elata Roxb) in The 1 District of Bohol, PhilippinesDocumento23 páginasSpatial Distribution of Buri Mother Plant (Corypha Elata Roxb) in The 1 District of Bohol, PhilippinesCheann PlazaAún no hay calificaciones

- Growing Bamboo for Food and Erosion ControlDocumento50 páginasGrowing Bamboo for Food and Erosion ControlDante Lepe GallardoAún no hay calificaciones

- Philippine National Report On Bamboo and RattanDocumento50 páginasPhilippine National Report On Bamboo and Rattanwcongson100% (1)

- IntroductionDocumento3 páginasIntroductionRodel MarataAún no hay calificaciones

- Biochemistry of Bitterness in Bamboo ShootsDocumento8 páginasBiochemistry of Bitterness in Bamboo ShootsKuo SarongAún no hay calificaciones

- Philippine National Report On Bamboo and RattanDocumento57 páginasPhilippine National Report On Bamboo and RattanolaAún no hay calificaciones

- Phytochemical Screening, Antimicrobial and Cytotoxicity Properties ofDocumento48 páginasPhytochemical Screening, Antimicrobial and Cytotoxicity Properties ofRyan HermosoAún no hay calificaciones

- Peta Research Group 5 EnscieDocumento4 páginasPeta Research Group 5 EnscieNaina NazalAún no hay calificaciones

- Vol 12 No 2 4 Bamboo ShootsDocumento8 páginasVol 12 No 2 4 Bamboo ShootsAllanAún no hay calificaciones

- Cahulugan J. Revised Thesis ProposalDocumento19 páginasCahulugan J. Revised Thesis ProposalJonna CahuluganAún no hay calificaciones

- Bamboo's Economic and Ecological BenefitsDocumento4 páginasBamboo's Economic and Ecological BenefitsBLADE LiGerAún no hay calificaciones

- Bamboo Biodiversity AsiaDocumento72 páginasBamboo Biodiversity AsiaEverboleh ChowAún no hay calificaciones

- Ielts Reading A Wonder PlantDocumento5 páginasIelts Reading A Wonder PlantDimpleAún no hay calificaciones

- Nutritional Properties of BambooDocumento17 páginasNutritional Properties of BambooCosmin M-escuAún no hay calificaciones

- Bamboo Cultivation Provides Sustainable Livelihood for Poor FarmersDocumento10 páginasBamboo Cultivation Provides Sustainable Livelihood for Poor Farmersanashwara.pillaiAún no hay calificaciones

- Underutilized Plant Resources in Tinoc, Ifugao, Cordillera Administrative Region, Luzon Island, PhilippinesDocumento15 páginasUnderutilized Plant Resources in Tinoc, Ifugao, Cordillera Administrative Region, Luzon Island, Philippinespepito manalotoAún no hay calificaciones

- The Cultivation of White Oyster MushroomsDocumento17 páginasThe Cultivation of White Oyster MushroomsJohn Mark NovenoAún no hay calificaciones

- Reading Passage 1: Bamboo, A Wonder PlantDocumento11 páginasReading Passage 1: Bamboo, A Wonder PlantLinh NhiAún no hay calificaciones

- EFYI Shajarkari: Diminishing Indigenous Tree Species in PunjabDocumento10 páginasEFYI Shajarkari: Diminishing Indigenous Tree Species in PunjabEco Friends Youth InitiativeAún no hay calificaciones

- Thesis About Bamboo ShootsDocumento5 páginasThesis About Bamboo Shootsuwuxovwhd100% (2)

- Bamboo Biodiversity Asia PDFDocumento72 páginasBamboo Biodiversity Asia PDFGultainjeeAún no hay calificaciones

- Bamboo PropagationDocumento7 páginasBamboo PropagationHamid SellakAún no hay calificaciones

- Actual Test 3Documento10 páginasActual Test 3trantruonggiabinhAún no hay calificaciones

- Group 18 - Literature Review - Coconut FiberboardDocumento13 páginasGroup 18 - Literature Review - Coconut FiberboardIsrael Pope100% (1)

- Constraints in Sustainable Bamboo Development in KeralaDocumento139 páginasConstraints in Sustainable Bamboo Development in Keralac_surendranathAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Draft 2.1Documento6 páginasResearch Draft 2.1shariagmamergaAún no hay calificaciones

- ACTUAL TEST-A Wonder PlantDocumento6 páginasACTUAL TEST-A Wonder PlantKishi GamerAún no hay calificaciones

- Feasibility of Banana Stem Fiber As An Ecobag - Chapter 1Documento9 páginasFeasibility of Banana Stem Fiber As An Ecobag - Chapter 1Rubilee Ganoy100% (1)

- Bamboo Shoot ProcessingDocumento38 páginasBamboo Shoot Processingपार्थिव चौधरी100% (1)

- Proposal Non-Timber Forest ProductDocumento13 páginasProposal Non-Timber Forest ProductJessiemaeAún no hay calificaciones

- Proposal Non-Timber Forest ProductDocumento13 páginasProposal Non-Timber Forest ProductJessiemae100% (1)

- Development, Quality Characteristics and Consumer Testing of Pie Utilizing Pili Pulp (Canarium Ovatum), Saba Banana (Musa Balbisiana) and Young Coconut Meat (Cocos Nucifera L)Documento14 páginasDevelopment, Quality Characteristics and Consumer Testing of Pie Utilizing Pili Pulp (Canarium Ovatum), Saba Banana (Musa Balbisiana) and Young Coconut Meat (Cocos Nucifera L)International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyAún no hay calificaciones

- BAMBOARD: Dried Bamboo Leaves (Bambusa Bambos) and Cassava Paste (Manihut Esculenta) CorkboardDocumento18 páginasBAMBOARD: Dried Bamboo Leaves (Bambusa Bambos) and Cassava Paste (Manihut Esculenta) Corkboardmy accountAún no hay calificaciones

- Bamboo: Polytechnic University of The Philippines Industrial Engineering DepartmentDocumento18 páginasBamboo: Polytechnic University of The Philippines Industrial Engineering DepartmentClydelle Garbino PorrasAún no hay calificaciones

- Ethnic Fermented Foods of The Philippines With Reference To Lactic Acid Bacteria and YeastsDocumento19 páginasEthnic Fermented Foods of The Philippines With Reference To Lactic Acid Bacteria and YeastsIssa AvenaAún no hay calificaciones

- Benefit Cost Analysis of Bamboo Plantations in The PhilippinesDocumento12 páginasBenefit Cost Analysis of Bamboo Plantations in The PhilippinesBloom EsplanaAún no hay calificaciones

- Group 1 PR2 C2Documento18 páginasGroup 1 PR2 C2antonialmasco786Aún no hay calificaciones

- Constraints in sustainable development of bamboo resources in KeralaDocumento139 páginasConstraints in sustainable development of bamboo resources in KeralaevanyllaAún no hay calificaciones

- Sip - Sample (Utilization of Peanut Shells As An Alternative Pencil Body)Documento32 páginasSip - Sample (Utilization of Peanut Shells As An Alternative Pencil Body)Jeremiah IldefonsoAún no hay calificaciones

- Sip - Sample (Utilization of Peanut Shells As An Alternative Pencil Body)Documento32 páginasSip - Sample (Utilization of Peanut Shells As An Alternative Pencil Body)Jiirem Arocena50% (2)

- Bamboo Tissue Culture Green GoldDocumento13 páginasBamboo Tissue Culture Green GoldVishnu Varthini BharathAún no hay calificaciones

- Rhean Jay.132,, KamagongDocumento21 páginasRhean Jay.132,, KamagongJunalyn Villafane50% (2)

- Bamboo Shoots' Biochemistry of BitternessDocumento7 páginasBamboo Shoots' Biochemistry of BitternessKuo SarongAún no hay calificaciones

- Field Manual For Propagation of Bamboo in North-East IndiaDocumento18 páginasField Manual For Propagation of Bamboo in North-East IndiamobyelectraAún no hay calificaciones

- Trends in Cassava Leaf NutritionDocumento12 páginasTrends in Cassava Leaf NutritionAlejandra OspinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Research PapaerDocumento6 páginasResearch PapaerChris TengAún no hay calificaciones

- PlantpeoplepaperfinalDocumento11 páginasPlantpeoplepaperfinalapi-256107840Aún no hay calificaciones

- Banana Peels As Paper Final OutputDocumento20 páginasBanana Peels As Paper Final OutputA - CAYAGA, Kirby, C 12 - HermonAún no hay calificaciones

- Assignment 9 - SAGSAGAT, SHAIRA JOYCE A. BSHM2ADocumento4 páginasAssignment 9 - SAGSAGAT, SHAIRA JOYCE A. BSHM2AShaira Arrocena SagsagatAún no hay calificaciones

- Bamboo A Wonder PlantDocumento4 páginasBamboo A Wonder Planthongpk.2006Aún no hay calificaciones

- Potential uses of banana by-products as renewable resourcesDocumento19 páginasPotential uses of banana by-products as renewable resourcesIsmail RahimAún no hay calificaciones

- Bamboo ChipsDocumento1 páginaBamboo ChipsSuave RevillasAún no hay calificaciones

- Avila - STS Activity 2Documento5 páginasAvila - STS Activity 2Jannine AvilaAún no hay calificaciones

- Young Bamboo Culm FlourDocumento6 páginasYoung Bamboo Culm FlourBoodjieh So ImbaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Whys of Behaviour PDFDocumento30 páginasThe Whys of Behaviour PDFmar8a8bel8n8pyrihAún no hay calificaciones

- Bicycle Frame Building Techniques in the USADocumento45 páginasBicycle Frame Building Techniques in the USARam ShewaleAún no hay calificaciones

- Botanical Actions Reference Sheet: Botanical Action Description Physiology ExamplesDocumento2 páginasBotanical Actions Reference Sheet: Botanical Action Description Physiology ExamplesDeo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- Ubi production guide covers harvesting, postharvest handling and storageDocumento3 páginasUbi production guide covers harvesting, postharvest handling and storageDeo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- Medicines 03 00025Documento16 páginasMedicines 03 00025Syed Iftekhar AlamAún no hay calificaciones

- The History of Animal WelfareDocumento49 páginasThe History of Animal WelfareRicardo GamboaAún no hay calificaciones

- Animal Parasites PDFDocumento730 páginasAnimal Parasites PDFDeo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- Animal Parasites PDFDocumento730 páginasAnimal Parasites PDFDeo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- UBI-Vegetable Production Guide - Beta - 356402Documento3 páginasUBI-Vegetable Production Guide - Beta - 356402Deo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- Bamboo Farm September 1 2020 1Documento15 páginasBamboo Farm September 1 2020 1Deo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- Ube Production GuideDocumento13 páginasUbe Production GuideAmante Malabago Neths100% (3)

- Bamboo Farm September 1 2020 1Documento15 páginasBamboo Farm September 1 2020 1Deo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- Magnetic Attraction (Joseph R Plazo) .PDF - NLP Info CentreDocumento47 páginasMagnetic Attraction (Joseph R Plazo) .PDF - NLP Info CentreDeo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- Making Scents of Smell Manufacturing and ConsumingDocumento24 páginasMaking Scents of Smell Manufacturing and ConsumingDeo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- Ube Production GuideDocumento13 páginasUbe Production GuideAmante Malabago Neths100% (3)

- Essential Oils and Their Applications-A Mini Review: ArticleDocumento14 páginasEssential Oils and Their Applications-A Mini Review: ArticledeviAún no hay calificaciones

- The Therapeutic Benefits of Essential Oils: February 2012Documento25 páginasThe Therapeutic Benefits of Essential Oils: February 2012Syed Iftekhar AlamAún no hay calificaciones

- Updated Franchise PresentationDocumento51 páginasUpdated Franchise PresentationDeo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- Ijbbv13n2 04Documento8 páginasIjbbv13n2 04Deo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- Updated Franchise PresentationDocumento51 páginasUpdated Franchise PresentationDeo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- C. Calvin Jones - Big Blue Book of Bicycle Repair-Park Tool Company (2013) PDFDocumento228 páginasC. Calvin Jones - Big Blue Book of Bicycle Repair-Park Tool Company (2013) PDFHector Valdez93% (14)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocumento15 páginas6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Decoding Pet Food Full ReportDocumento32 páginasDecoding Pet Food Full ReportDeo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- Citronella Production: I. General Description of The CropDocumento6 páginasCitronella Production: I. General Description of The CropDeo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- PBSAI Membership Application Form MQMDocumento2 páginasPBSAI Membership Application Form MQMDeo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- The Therapeutic Benefits of Essential Oils: February 2012Documento25 páginasThe Therapeutic Benefits of Essential Oils: February 2012Syed Iftekhar AlamAún no hay calificaciones

- PBSAI Membership Application Form - TSUDocumento2 páginasPBSAI Membership Application Form - TSUDeo DoktorAún no hay calificaciones

- The History of Animal WelfareDocumento49 páginasThe History of Animal WelfareRicardo GamboaAún no hay calificaciones

- Medicines 03 00025Documento16 páginasMedicines 03 00025Syed Iftekhar AlamAún no hay calificaciones

- The History of Animal WelfareDocumento49 páginasThe History of Animal WelfareRicardo GamboaAún no hay calificaciones

- Timeline of Spanish Colonization of The PhilippinesDocumento8 páginasTimeline of Spanish Colonization of The Philippinesjulesubayubay542894% (36)

- PROMISED LAND The Cry of The Poor PeasantsDocumento78 páginasPROMISED LAND The Cry of The Poor PeasantsArmstrong BosantogAún no hay calificaciones

- Jordan Doy A. AdajarDocumento4 páginasJordan Doy A. AdajarGretchel PontilarAún no hay calificaciones

- Als Agreement or MOADocumento1 páginaAls Agreement or MOAchacha g.Aún no hay calificaciones

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocumento2 páginasCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsAún no hay calificaciones

- Final Industry ProfileDocumento2 páginasFinal Industry ProfileCharlie LebecoAún no hay calificaciones

- BRIEFER - Interpellation On Brgy Creation BillsDocumento23 páginasBRIEFER - Interpellation On Brgy Creation BillsJaye Querubin-FernandezAún no hay calificaciones

- History of The Philippine FlagDocumento12 páginasHistory of The Philippine FlagSer Loisse MortelAún no hay calificaciones

- Emilio Aguinaldo 1899-1901: 2. Manuel L. Quezon, 1935-1944Documento6 páginasEmilio Aguinaldo 1899-1901: 2. Manuel L. Quezon, 1935-1944LucasAún no hay calificaciones

- Group 2Documento14 páginasGroup 2desiree viernesAún no hay calificaciones

- Position Paper in RPH 2Documento3 páginasPosition Paper in RPH 2Mirely BatacanAún no hay calificaciones

- Ra 8042Documento9 páginasRa 8042vherny_corderoAún no hay calificaciones

- Certificates LayoutDocumento8 páginasCertificates LayoutJam R LoremaAún no hay calificaciones

- Rizal's Letter to Young Women of MalolosDocumento94 páginasRizal's Letter to Young Women of Malolosclint ford EspanolaAún no hay calificaciones

- FISH1016ra Davao e PDFDocumento9 páginasFISH1016ra Davao e PDFPhilBoardResultsAún no hay calificaciones

- Pasion Activity#1Documento2 páginasPasion Activity#1Camille PasionAún no hay calificaciones

- 2004-2005 Annual ReportDocumento40 páginas2004-2005 Annual ReportInggar PradiptaAún no hay calificaciones

- Reflection Paper Ambisyon 2040 &filipinas 2000Documento2 páginasReflection Paper Ambisyon 2040 &filipinas 2000Marjorie DodanAún no hay calificaciones

- Module 2 Lesson 6 - Content AnalysisDocumento12 páginasModule 2 Lesson 6 - Content AnalysisKyle Patrick MartinezAún no hay calificaciones

- Jinggoy EstradaDocumento9 páginasJinggoy EstradaJustine June DuranaAún no hay calificaciones

- 4.C. Certificate of EnrolmentDocumento4 páginas4.C. Certificate of EnrolmentJoseph Dominic L. LagulosAún no hay calificaciones

- History of Table Tennis and ArnisDocumento3 páginasHistory of Table Tennis and ArnisMarvin Lubongan DacuagAún no hay calificaciones

- Life and Works of RizalDocumento5 páginasLife and Works of RizalChrissa AranelaAún no hay calificaciones

- Kalayaan: By: Angelique Mae A. PlejeDocumento8 páginasKalayaan: By: Angelique Mae A. PlejeAngelique Mae PlejeAún no hay calificaciones

- Rio L. Magpantay, MD, Phsae, Ceso Iii Director IV Department of Health Carig Norte, Tuguegarao CityDocumento1 páginaRio L. Magpantay, MD, Phsae, Ceso Iii Director IV Department of Health Carig Norte, Tuguegarao CityMelizen Leones AddunAún no hay calificaciones

- Spanish & American Influence on Philippine ArchitectureDocumento33 páginasSpanish & American Influence on Philippine ArchitectureEdrick G. EsparraguerraAún no hay calificaciones

- Kwok PedroDocumento7 páginasKwok PedroRico Jay Musni100% (1)

- Juan de Plasencia: "Customs of The Tagalogs"Documento45 páginasJuan de Plasencia: "Customs of The Tagalogs"Rommel Soliven Estabillo0% (1)

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocumento2 páginasCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsAún no hay calificaciones

- Updated 2 Campo Santo de La LomaDocumento64 páginasUpdated 2 Campo Santo de La LomaRania Mae BalmesAún no hay calificaciones