Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Offshoring and Its Effects On The Labour Market and Productivity: A Survey of Recent Literature

Cargado por

osefresistanceDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Offshoring and Its Effects On The Labour Market and Productivity: A Survey of Recent Literature

Cargado por

osefresistanceCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Offshoring and Its Effects on the

Labour Market and Productivity:

A Survey of Recent Literature

Calista Cheung and James Rossiter, International Department, Yi Zheng, Research

Department

Firms relocate production processes ver the past couple of decades, the lower-

internationally (offshore) primarily to achieve

cost savings. As offshoring becomes an

increasingly prominent aspect of the

O ing of trade and investment barriers as well

as technological progress in transportation

and communications have facilitated the

globalization of production processes. Firms increas-

globalization process, understanding its effects ingly take advantage of the cost savings and other

on the economy is important for handling benefits that result from making or buying inputs

the policy challenges that arise from structural where they can be produced more efficiently. This

phenomenon of production relocation across national

changes induced by globalization in general. boundaries is generally known as offshoring.1 Under-

In advanced economies, offshoring of materials standing the implications of offshoring in the current

context is an important step towards handling the

used in manufacturing has risen steadily over opportunities and challenges of globalization as it

the past two decades. The scale of offshoring matures. This article contributes to such understand-

in services is much smaller, but has grown ing by summarizing some key findings in the litera-

faster than that of materials since the mid- ture on the impact of offshoring on employment,

1990s. The intensity of offshoring in Canada wages, and productivity in developed economies.

Note that while offshoring of services is still in its

has been higher than in many other advanced infancy, it merits as close a study as that of manufac-

economies, probably because of our close turing offshoring, given its unique characteristics and

economic relationship with the United States. greater potential for growth.

Offshoring has not exerted a noticeable impact While offshoring can help businesses improve their

profitability, and host countries (i.e., providers of off-

on overall employment and earnings growth shored goods and services) generally welcome the

in advanced economies, but it has likely resulting creation of jobs, its macroeconomic effect on

contributed to shifting the demand for home countries (i.e., importers of offshored inputs)

labour towards higher-skilled jobs. remains a subject of debate. There has long been

concern that labour markets in developed economies

There appear to be some positive effects of have faced adjustment challenges associated with

offshoring on productivity consistent with

theoretical expectations, but such effects 1. This broad definition holds regardless of whether the counterparty to the

offshoring firm is an independent firm or a foreign affiliate. Outsourcing, on

differ by country. the other hand, emphasizes the relocation of production processes across firm

boundaries.

BANK OF CANADA REVIEW AUTUMN 2008 15

offshoring to low-wage countries, first in the manu- are used as intermediate inputs.2 For example, between

facturing sector and then services. The concerns are 2000 and 2006, world exports of intermediate goods

summarized as follows: If you can describe a job grew at an annual rate of 14 per cent, compared with a

precisely, or write rules for doing it, it's unlikely to 9 per cent rate for final goods (Chart 1).3

survive. Either we'll program a computer to do it, or Following common practice, we quantify the intensity

we'll teach a foreigner to do it (Wessel 2004). of offshoring by country and by industry using two

The gains to the overall economy as a result of offshor- ratios: (a) imported intermediate inputs over gross

ing, on the other hand, have received less publicity, output, and (b) imported intermediate inputs over

partly because they usually do not occur immediately their total usage. Both are calculated from standard

and thus are more difficult to associate directly with industry datasets maintained by national statistical

offshoring. Nevertheless, research suggests that off- agencies and thus allow for international and cross-

shoring may contribute to productivity gains, promote industry comparisons. While measures based on

skills upgrading, enhance the purchasing power of import content are derived under some restrictive

consumers via lower import prices, and reduce the assumptions and do not convey a complete picture of

exposure of exporters to exchange rate fluctuations by

providing a natural hedge. Chart 1

Offshoring has likely played an important role in World Exports of Intermediate and Final Goods and

shifting the composition of industries in favour of Services

those more aligned with the comparative advantages

of the home economy. Furthermore, the widening of 2000 = 100

the global supply base as a result of offshoring tends 250 250

to raise competitive pressures and leads to changes in Intermediate

relative prices, such as those of standardized manu- goods

200 200

factured goods versus metals and oil, or those of call

centre services versus architectural design. Despite

their still limited impact, such changes have the 150 150

potential to grow in prominence and thus warrant Intermediate Final goods

services

careful consideration, along with domestic circum-

100 100

stances, in conducting effective economic policies. For

example, the productivity effect from offshoring could

influence the growth potential of the economy, while 50 50

persistent relative price movements could affect infla-

tion expectationsand both may lead to changes in

0 0

inflationary pressure that need to be taken into 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006

account by monetary policy-makers (Carney 2008).

Note: Intermediate goods: agricultural raw material, fuel and

The remainder of the article begins with some recent mining products, iron and steel, chemicals and other semi-

finished goods

developments in offshoring in both the international Final goods: all merchandise except intermediate goods

and Canadian context. This leads to a discussion of Intermediate services: commercial services excluding travel

and transportation

what drives offshoring. A survey of the empirical evi- Source: World Trade Organization

dence regarding the impact of offshoring on labour

markets and productivity follows, highlighting find- 2. Throughout this article, the term intermediate inputs means goods (mate-

ings for Canada. Finally, the article concludes with a rial inputs) and services (service inputs) that undergo further processing

summary of the key results and a brief discussion of before being sold as final. For example, rolled steel and car engines are mate-

rial inputs to motor vehicle manufacturing, while call centre services and

the future of offshoring. accounting are typical examples of service inputs to many industries.

3. The globalization of production has also led to multiple border crossings of

Recent Trends in Offshoring semi-finished goods with incremental value added at each production stage

(Yi 2003), further boosting the share of intermediate goods in overall trade.

Growth in offshoring on a global scale is evident in the Indeed, as of 2006, 40 per cent of world merchandise exports consisted of

steady expansion of trade in goods and services that intermediate goods.

16 BANK OF CANADA REVIEW AUTUMN 2008

the globalization of production (see Box), they are Chart 2

likely indicative of the general trends. G-7 Offshoring of Non-Energy Inputs

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF Per cent of gross output

2007), imports of material and service inputs in 2003

14 14

represented about 5 per cent of gross output in

advanced economies belonging to the Organisation 12 Canada 12

for Economic Co-operation and Development

(OECD).4 Within the G-7, a wide dispersion of scale 10 United 10

exists, ranging from 2 to 3 per cent in the United Kingdom

States and Japan, to more than 10 per cent in Can- 8 8

Italy

ada (Chart 2). In addition, starting in the 1990s, Can-

6 6

ada, Italy, and Germany saw a noticeable increase in

the degree of offshoring. Germany France

4 4

United States

2 2

Japan

The manufacturing sector is most 0 0

1980 1985 1990 1995 2000

affected by offshoring because of its

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook

greater openness to trade and high (April 2007)

intermediate-input content.

The manufacturing sector is most affected by offshor-

ing because of its greater openness to trade and high

intermediate-input content in the production process.

In the advanced OECD economies, the weighted Chart 3

average share of imported material inputs in manu- Offshored Material Inputs in the Manufacturing

facturing gross output rose from 6 per cent in 1981 to Sector

10 per cent in 2001 (Chart 3).5 The ratio in Canada is

almost three times as high. Canadian manufacturers Per cent of manufactured gross output

engage intensively in trade in intermediate inputs 30 30

with the United States, given the existence of a tightly

knit cross-border supply chain arising from the geo- 25 25

graphical proximity of the two countries and the

Canada

signing of trade agreements that have fostered a large 20 20

volume of regional investment and trade flows.6, 7 A

15 15

4. Advanced OECD economies in IMF (2007) include Australia, Canada, Canada excluding motor

France, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the 10 vehicles and parts 10

United States.

Advanced OECD economies

5. Shares are weighted using share of nominal gross domestic product 5 5

denominated in U.S. dollars. Data from IMF (2007).

6. These were the Canada-United States Auto Pact (1965), the Canada-United

0 0

States Free Trade Agreement (1989), and the North American Free Trade

1981 1986 1991 1996 2001

Agreement (1994).

Note: Advanced economies include Australia, Canada, France,

7. While the trade and investment linkages among European countries are

Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and

also strong, these countries have, on average, a lower offshoring intensity the United States

than Canada. This is somewhat puzzling. One possible explanation is the OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Devel-

labour market rigidity in some of these countries, which has prevented firms opment

from reaping the expected benefits of offshoring, thus dampening the motiva- Source: International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook

tion to offshore. (April 2007), Bank of Canada

BANK OF CANADA REVIEW AUTUMN 2008 17

Issues with Imputed Import-Based Measures of Offshoring

Since official statistics do not separate an industrys could be delegated under contract to a different coun-

intermediate inputs into domestic and imported com- try so that the final product is sent directly from that

ponents, virtually all measures of offshoring are con- location to serve its consumers. These situations gen-

structed from national input-output (I-O) tables, erate productivity and labour market effects that are

under the assumption that the import share of a com- not captured by the intermediate-import-based meas-

modity used as an intermediate input is the same as ures of offshoring.

the share of imports in total domestic consumption of

this commodity (following Feenstra and Hanson 1996,

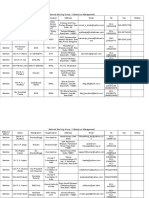

Table B1

1999).1 As such, the differences in offshoring among

industries largely reflect different commodity compo- Share of Material Inputs Imported into Canada

sition by industry, since no inter-industry variation in Percentage

import propensity is allowed, by construction. How

Industries Shares reported by

accurate are such imputations? Table B1 illustrates the

potential measurement bias for the manufacturing Innovation Input-output Difference

industries.2 The second column shows the average Survey 2005 tables

share of material inputs imported, as reported by (200204) (2003)

plants responding to a Statistics Canada survey.3 The

Computer and electronics 49.9 71.8 21.9

third column lists the imputed share from the I-O

Transportation equipment 42.6 65.4 22.8

table. The imputed value exceeds the survey-based Textile mills and textile

value for almost all industries. For the manufacturing products 53.3 62.5 9.2

sector as a whole, the discrepancy amounts to 16 per- Plastics and rubber 42.7 57.2 14.5

centage points. While the survey-based direct meas- Miscellaneous

ure is subject to sampling bias (among other things), manufacturing 30.9 55.4 24.5

the comparison serves as a reminder of the data chal- Apparel and leather 43.6 54.3 10.7

lenges faced by researchers. Electrical equipment 42.2 53.5 11.3

Machinery 31.8 53.3 21.5

Even with the availability of industry data that sepa- Petroleum and coal 24.0 47.7 23.7

rately quantify imported inputs, a complete account Chemical 39.7 44.1 4.4

of the extent of international production relocation Printing 25.6 43.2 17.6

may still be difficult. Trade-based offshoring measures Primary metal 30.3 40.8 10.5

rely on the assumption that all offshored inputs will Furniture 17.8 37.0 19.2

be imported by the home country before being inte- Fabricated metal 24.0 33.7 9.7

grated into the final product. However, this misses Non-metallic mineral 22.6 26.9 4.3

those cases where the final link in the global value Paper 31.6 26.9 -4.7

Food and beverage

chain is not located in the home country. For example,

and tobacco 16.4 19.8 3.4

a final stage of production could be carried out in an Wood 10.8 11.9 1.1

offshore location before the product is imported in its Total manufacturing 29.0 44.7 15.7

final form. Alternatively, the entire production process

Source: Statistics Canada: Survey of Innovation 2005 as reported in Tang

and do Livramento (2008), and input-output tables 2003; authors own

1. The annual I-O tables provide time series of detailed information on the

calculations

flows of goods and services that comprise industry production processes.

2. For an evaluation pertaining to business services, see Yuskavage, Strass-

ner, and Medeiros (2008).

3. Statistics Canada, Survey of Innovation (2005), reported in Tang and

do Livramento (2008); table statistics based on a sample of 5,653 manufac-

turing plants, or 36 per cent of the population.

18 BANK OF CANADA REVIEW AUTUMN 2008

Chart 4 recent study finds that roughly 70 per cent of the

Offshored Service Inputs in the Overall Economy Canada-U.S. bilateral merchandise trade is in compo-

nents within the same industry (Goldfarb and Beck-

Per cent of gross output man 2007). The North American motor vehicle and

1.8 1.8

parts industry offers a prime example in this regard,

1.6 1.6 with 45 per cent of its gross output represented by

Canada imports and accounting for some 30 per cent of all the

1.4 1.4

material inputs imported by the entire manufacturing

1.2 1.2 sector. As demonstrated in Chart 3, however, the high

1.0 1.0 propensity to import is also evident in other Canadian

Advanced OECD

economies manufacturing industries.

0.8 0.8

Imports of service inputs by the overall economy, on

0.6 0.6 the other hand, constitute a fairly low share of gross

0.4 0.4 output, reaching 1 per cent only after 1995. Nevertheless,

since the mid-1990s, this share has grown at a faster

0.2 0.2

rate than its materials counterpart. The ratio in Canada

0 0 is just slightly higher than the average of advanced

1981 1986 1991 1996 2001

OECD economies (Chart 4).

Note: Advanced economies include Australia, Canada, France,

Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and A more detailed examination of industry-level data

the United States for Canada reveals three industries with an above-

OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Devel-

opment average share of imported material: transportation

Source: International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook and warehousing, manufacturing, and information

(April 2007), Bank of Canada.

Chart 5

Imported Share of Material Inputs, by Industry*

%

60 60

1980

50 50

1990

40

2003 40

30 30

20 20

10 10

0 0

To

A ishi

M xtra

Co

Re

Tr are

In ultu

FI

Pr chn

A dr

A dr

A od

O exc ini an

gr ng

til

dm e

rts e

cc s

th ep st

fo ra

in ct

an

RE

of ic

ho

an ho

f

te

an

an

fo

( m

ta

ta

ns

er t p ra

ic ,

iti

om erv

in io

rm l i

es al

, e re

lb

uf

il

sp us

le

in ed

ad atio [72

tru

L

ul an

es

g n

se ub tio

sio se

tra

ac

sa

nt at

or in

at nd

ist ia

us

m ce

[5

tu d

ct

an [2

rv li n)

er io

[2

c

le

io us

tu

ta g

od s

de

na rv

ra ti

in

re hu

2

io

d 1]

ic c [8

ta n

n tr

2]

rin

tio [4

tra

tio on

es

,f n

l, ice

i

53

oi

[4

es

in [7

an ie

ss

n 8

[2

or tin

sc s

d

n, se

la

m 1]

]

d s[

e

an 49

n ]

[3

3]

es g

ie [5

ec

en

w

nd

[4

45

nt 4]

1

d ]

try [1

to

t,

1]

ste ice

ifi

d

ga

33

r

, 1]

r

c,

51

s

v

]

m s [5

1]

an

]

an 6]

d

ag

em

en

t,

* Numbers in brackets represent North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes.

FIREL = Finance, insurance, and real estate

Source: Statistics Canada

BANK OF CANADA REVIEW AUTUMN 2008 19

Chart 6 and cultural industries (Chart 5).8 Within manufac-

Offshoring of Material Inputs by Manufacturing turing, computers and electronics, transportation

Industries equipment, and textile products are the most offshore-

intensive industries. Interestingly, while the motor

1961 = 100 vehicle and parts industry drove the upward trend in

250 250 material offshoring in Canada in the 1960s and early

Computers and

Other

electronics

1970s, its import share of material inputs has remained

manufacturing

200 200

flat in the past three decades, while a broad-based

surge in offshoring has taken place in other manufac-

Motor vehicle turing industries (Chart 6).

and parts

150 150

100 100

Textile mills and Since the mid-1990s, the share of

textile products

Other transportation imports of service inputs in gross output

50 50

equipment

has grown at a faster rate than

its materials counterpart.

0 0

1961 1966 1971 1976 1981 1986 1991 1996 2001

Source: Statistics Canada

For service inputs, the import proportion in the

Canadian business sector increased to 7.6 per cent in

8. All industries shown in the chart are at the 2-digit level, the highest level of

aggregation according to the North American Industry Classification System.

Chart 7

Imported Share of Service Inputs, by Industry

%

12 12

1980

10 1990 10

2003

8 8

6 6

4 4

2 2

0 0

To

A hi

M xtra

Co

Re

Tr are

In ultu

FI

Pr chn

A dr

A dr

A od

O exc ini and

gr ng

til

dm e

rts e

cc s

th ep st

fo ra

in ct

an

RE

of ic

ho

an ho

fis

te

an

an

fo

( dm

ta

ta

ns

er t p ra

ic ,

iti

om erv

in io

rm l i

es al

, e re

lb

uf

il

sp us

le

in ed

a

tru

L

ul an

es

g n

se ub tio

sio se

tra

ac

sa

nt at

or in

at nd

ist ia

us

m ice

[5

tu d

ct

an [2

rv li n)

er io

c

[2

m

le

io us

tu

ta g

od s

de

na rv

ra ti

in

re hu

2

io

d 1]

ic c [8

t

n tr

2]

rin

tio [4

tra

tio on

a

es

,f n

l, ice

at 7

5

oi

[4

es

i

an ie

n

ss

3]

n 8

io 2]

[2

or tin

sc s

de

n

la

m 1]

d s[

,

an 49

n

[3

n

3]

es g

ie [5

ec

en

w

[

nd

[4

45

[

nt 4]

1

d ]

try [1

7

to

t,

1]

s

ste ce

ifi

ga

33

r

e

, 1]

r

c,

51

s

vi

]

m s [5

1]

an

]

an 6]

d

ag

em

en

t,

* Numbers in brackets represent North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) Codes.

FIREL = Finance, insurance, and real estate

Source: Statistics Canada

20 BANK OF CANADA REVIEW AUTUMN 2008

Chart 8 when the cost to do so is lower than the cost of domestic

Origin of Imported Industrial Intermediate Inputs production, enhancing the profits of home-country

firms. This section discusses the recent drivers of

% offshoring and presents survey evidence on the benefits

100 100 and costs associated with it.

90 90 Improvements in information and communications

80 80 technology (ICT), especially since the 1990s, have

70 70

reduced the adjustment and transactions costs faced

by offshoring firms (Abramovsky and Griffith 2005). As

60 60

ICT has fallen in price, it has been widely adopted by

50 50 firms that are offshoring material inputs, resulting in

40 40 immensely improved transportation logistics, inven-

tory management, and production coordination. Off-

30 30

shoring of ICT hardware itself has contributed

20 20

significantly to price declines of ICT, which has in turn

10 10 facilitated the offshoring process in general (Mann

0 0 2003). Service offshoring has become more feasible in

1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 the past decade, owing to advances in ICT. The

United deployment of fast global telecommunications infra-

States Others Mexico

European Asia excluding Middle

structure, digital standardization (which facilitates the

Union East and China China sharing of structured data across different information

systems), and broadened access to lower-cost ICT

Source: Industry Canada equipment has enabled instant interaction between

parties across the globe, reducing the importance of

2003, from 4.6 per cent in 1980 (Chart 7). In 2003, busi-

physical proximity in service delivery. The importance

ness services, finance, and insurance accounted for

of ICT to service offshoring is emphasized by van Wel-

more than 70 per cent of imported service inputs,

sum and Vickery (2005), who specify four criteria that

while the share of software development and compu-

make a service occupation offshorable: intensive use

ter services was only 3 per cent (Baldwin and Gu

of ICT; producing an output that can be traded or

2008).

transmitted via the Internet; highly codifiable knowl-

Canadian firms have traditionally imported most of edge content; and no face-to-face contact require-

their intermediate inputs from the United States ments.

(Chart 8). In recent years, however, more imports have

originated from the European Union, China, and

other countries, leading to a decline in the U.S. share

from 67 per cent in 1998 to 51 per cent in 2007.9 Improvements in ICT have reduced

the adjustment and transactions

Factors Facilitating Offshoring costs faced by offshoring firms.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of offshoring.

The first involves offshoring of labour-intensive inter-

mediate inputs to developing countries, where cheaper

labour abounds. The second entails offshoring of Aside from ICT, a global shift towards more open

sophisticated inputs to industrialized economies to trade and investment policies, reductions in transpor-

benefit from more advanced technologies or economies tation costs, and improvements in transportation

of scale. The latter type of offshoring lowers the costs logistics (such as containerization and coordination

of capital-intensive goods and services for firms in the among different modes of transportation) has expe-

home country. Regardless of the type, firms offshore dited offshoring in recent years (Trefler 2005). For

instance, the accession of China to the World Trade

9. The increase in Chinas share is largely offset by a corresponding decline in

Organization in 2001 following decades of increasingly

the share of other Asian countries. open trade policies led to an important shift in the

BANK OF CANADA REVIEW AUTUMN 2008 21

global labour supply. In addition, the reduction of Chart 9

trade tariffs and quotas by the Canada-United States Source of G-7 Imports of Material Inputs

Free Trade Agreement (1989) and the North American

Free Trade Agreement (1994) substantially decreased %

the cost of offshoring between member countries. 0.7 0.7

1992

A wealth of survey evidence exists on the factors that 0.6 0.6

drive firms to offshore.10 The most commonly cited 2006

motive is cost reduction. Other reasons include firms 0.5 0.5

desire to focus on core business, to expand capacity, to

improve quality, and to create 24-hour operational 0.4 0.4

flexibility for services. Firms might also expect to ben-

0.3 0.3

efit from access to a skilled workforce, expansion into

rapidly growing markets, and a closer proximity to

0.2 0.2

customers (Trefler 2005).

The expected benefits from offshoring may not always 0.1 0.1

materialize, however. For example, firms offshoring

to developing countries must weigh the savings on 0 0

OECD Emerging Emerging Other

wages against coordination costs that would not oth- Asia Europe

erwise be incurred (Baldwin 2006). This is especially Note: The G-7 countries are Canada, France, Germany, Italy,

important for offshoring in services where the coordi- Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

nation between tasks is crucial. Other common chal- OECD = Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Devel-

opment

lenges faced by offshoring firms include uncertainty Source: OECD International Trade Statistics

surrounding the enforceability of contracts, issues

with quality control, poor communication with the

vendor, high costs of searching for the right partner,

and weak protection for proprietary rights. The diffi- Effects on the labour market

culty of learning how to offshore might also temporar-

Overall impact

ily mask some of the gains from offshoring.11 These

negative aspects may limit the scale of offshoring. The impact of offshoring on the labour markets of the

home country depends to a large extent on where the

inputs are imported from. While most G-7 economies

The Effects of Offshoring on continue to import the majority of their material inputs

Advanced Economies from other advanced economies, the share of imports

The global economy has experienced an important from emerging economies with abundant labour supply

shift in production arrangements and the composition has roughly doubled since the early 1990s (Chart 9). In

of labour supply. The ease with which firms are now terms of service inputs, Indias development as an

able to employ workers in foreign countries has important provider of offshore information technol-

increased the degree of job competition on a global ogy and call centre services illustrates the same point.

scale. This has the potential to significantly affect Given the rising share of imported inputs from low-

employment, wages, and productivity in countries wage countries, standard trade theory would suggest

involved in offshoring. These issues are the focus of that labour demand and wages in the import-compet-

the remainder of the article. ing industries of the home country would decline.12

Beyond what standard trade theory would predict,

trade in intermediate inputs may have more wide-

spread effects on employment and wages than trade

10. See, for example, Accenture (2004); Bajpai et al. (2004); Gomez and

Gunderson (2006); PriceWaterhouseCoopers (2005, 2008); and Gomez (2005).

11. Bajpai et al. (2004) note that 26 per cent of their survey respondents, 12. According to Bhagwati, Panagariya, and Srinivasan (2004), offshoring is

almost all of which had been in such arrangements for one year or less, were fundamentally a trade phenomenon that should therefore generate employ-

unsatisfied with their service outsourcing experience (four out of five involve ment and wage effects qualitatively similar to those from conventional trade

a foreign provider). in final goods.

22 BANK OF CANADA REVIEW AUTUMN 2008

Chart 10 Chart 11

Advanced Economies: Employment and Earnings Advanced Economies: Employment

Growth

1980 = 100

Percentage growth 140 140

3.0 3.0

130 130

2.5 2.5

Employment

Total

2.0 2.0 120 120

1.5 1.5

110 110

1.0 1.0

100 100

0.5 0.5 Low-skilled

sectors

0 0 90 90

Real labour

compensation

-0.5 -0.5

per worker

80 80

-1.0 -1.0 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005

1981 1986 1991 1996 2001 Note: Advanced economies = Australia, Canada, France,

Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and

Note: Advanced economies = Australia, Canada, France,

the United States

Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook

the United States

(2007)

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook

(2007)

in final goods and services, since it affects labour high-skilled labour when high-skilled tasks are off-

demand not only in import-competing sectors but also shored could prove temporary, since importing skill-

in sectors that use the imported inputs (Feenstra and intensive inputs typically leads to technological spillo-

Hanson 2003).13 Furthermore, to the extent that low- ver from more advanced host countries to the home

skilled activities are increasingly offshored to low- country and eventually boosts demand for skills.

wage countries, labour demand in the home country Chart 10 illustrates that it is indeed difficult to detect

is expected to be shifted towards high-skilled activi- any sustained slowdown in overall employment or

ties within industries, raising the skill premium for earnings growth in the advanced economies. In addi-

wages (Feenstra and Hanson 1996).14 tion, there appears to be no systematic association

In the long term, the offshoring of low-skilled tasks between cross-country differences in trade openness

should not affect aggregate employment levels, barring and labour market outcomes (OECD 2005). Granted,

impediments to the adjustment of relative wages and labour market developments at the aggregate level

demand for skilled versus unskilled labour. Moreover, mask the adjustment costs that can occur in the short

the initial loss of low-skilled jobs could be offset by the run, in the form of job displacement or earnings loss

creation of new jobs made possible by cost savings for certain workers. Several studies suggest that

resulting from offshoring (Bhagwati, Panagariya, and industries with increased exposure to international

Srinivasan 2004). Likewise, the decrease in demand for competition are associated with higher rates of tempo-

rary unemployment (see OECD 2005 for a review).

The loss in earnings is found to be significantly larger

13. Egger and Egger (2005) also find that offshoring in one industry may have

important spillover effects arising from sectoral input-output interdependen- for trade-displaced manufacturing workers who

cies and worker flows triggered by expanding or contracting production in change industry (Kletzer 2001).

different sectors.

Shifts in the skill composition of labour demand and

14. Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg (2006a, 2006b) propose that the offshoring

of low-skilled tasks generates cost savings to sectors most reliant on low- wages

skilled labour, allowing output to expand in these sectors. The authors argue

that, if sufficiently large, this productivity effect may even push up the wages Many studies find evidence for OECD countries that

of low-skilled labour. increased offshoring is associated with slower growth

BANK OF CANADA REVIEW AUTUMN 2008 23

Chart 12 Chart 13

Advanced Economies: Real Labour Compensation Chinas Export Composition

per Worker

US$ billions

1980 = 100 700 700

130 130 High skill-intensive products

600 600

125 125 Low skill-intensive products

Total

120 120 500 500

115 115

400 400

110 Low-skilled 110

sectors 300 300

105 105

100 100

200 200

95 95

100 100

90 90

85 85 0 0

1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004

80 80

1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005

Source: OECD International Trade by Commodity Statistics

Note: Advanced economies = Australia, Canada, France,

Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and

the United States

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook

(2007)

in employment and wages of low-skilled labour rela- general, while offshoring has been found to affect both

tive to their high-skilled counterparts in the manufac- labour shares and wages significantly, the impact of

turing sector.15 Charts 11 and 12 show that, for the technological progress has been larger (IMF 2007;

advanced economies, growth in employment and Feenstra and Hanson 1999).

earnings in low-skilled intensive sectors has stagnated Furthermore, the overall influence of offshoring on the

relative to total employment and earnings growth.16 skill structure of labour demand and wages in the home

Although the relatively slower growth observed in country may evolve over time, along with changes in

low-skilled employment and earnings is consistent the composition of host countries (advanced versus

with the expected effects of increased offshoring of emerging economies), the nature of offshored opera-

low-skilled tasks, it may also be attributable to techno- tions (high-skilled versus low-skilled), and the skill

logical progress that favours high-skilled jobs.17In structure of the host country. On the last point, Chart 13

illustrates that low-wage countries such as China have

15. For example, Feenstra and Hanson (1996, 1999) conclude that offshoring shifted increasingly towards skill-intensive exports in

can account for 3050 per cent of the increase in relative demand for skilled

labour in U.S. manufacturing industries during the 1980s, and about 15 per recent years. As offshored inputs move up the skill

cent of the increase in their relative wages between 1979 and 1990. Using the ladder, the effect of offshoring on a home countrys

same method for the United Kingdom, Hijzen (2003) attributes 12 per cent of

labour demand by type of skills may become more

the increase in the relative wage gap during the 1990s to offshoring. For Can-

ada, Yan (2005) finds that a 1 percentage point increase in the use of imported difficult to quantify.

material inputs leads to an average 0.026 percentage point increase in the

wage share of skilled workers in the manufacturing sector.

Is service offshoring different?

16. The sector classification by skill level used here is from the IMF study Service offshoring has expanded rapidly in recent

(2007), which is based on calculations in Jean and Nicoletti (2002) on the aver- years. Unlike their manufacturing counterparts, the

age share of skilled workers in each sector across 16 OECD economies. The

study defines skilled workers as those having attained at least upper second-

service occupations that can be offshored are not usu-

ary education. Consequently, the trends illustrated do not capture possible ally characterized by low skill requirements. In the

within-sector shifts in skill level, but only shifts from low-skilled sectors to United States, displaced workers in tradable service

high-skilled sectors. This sector classification would also not capture the off-

shoring of low-skilled occupations that may have occurred within high-skilled

jobs tend to have greater educational attainment, as

sectors. Data at the sectoral level were only available up to 2001. well as higher skills and earnings, than those in manu-

17. It is also difficult to know whether these changes result from a shift in

final demand towards high-skilled-intensive products and services.

24 BANK OF CANADA REVIEW AUTUMN 2008

facturing (Jensen and Kletzer 2005).18 Its perceived ductivity, but also that highly productive firms take

threat to domestic high-skilled jobs in which the advantage of offshoring more than less-productive

United States has traditionally had a comparative ones. Despite this bias, empirical studies find evidence

advantage may be the reason that offshoring of serv- of productivity gains from offshoring, but the results

ice jobs has generated greater public concern in the differ somewhat by country. For example, in the

United States than has the offshoring of manufactur- United States, the offshoring of service inputs accounts

ing jobs. for a larger fraction of manufacturing productivity

The OECD (2005) finds limited evidence, however, gains than does the offshoring of material inputs

that the offshoring of business services has under- (Amiti and Wei 2006). Offshoring firms in the United

mined employment in industries providing such serv- States also tend to be outstanding in many regards

ices, although this may be because of generally (including productivity growth) prior to offshoring,

smaller trade flows and the relatively healthy employ- but continue to experience higher productivity gains

ment performance of this sector. After examining a once offshoring has begun (Kurz 2006). In Canada,

vast dataset by industry and occupation, Morissette material offshoring has significantly contributed to

and Johnson (2007) conclude that offshoring does not multifactor productivity gains, while there is no such

appear to be correlated with the evolution of employ- evidence from service offshoring (Baldwin and Gu

ment and layoff rates in Canada. Jensen and Kletzer 2008). Other evidence suggesting a causal link between

(2005) find that tradable service occupations in the offshoring and productivity growth is discussed in

United States experienced employment growth similar Olsen (2006).

to that of non-tradable service activities, although, at

the lowest skill levels, employment in tradable service

industries and occupations has declined. In other

words, the majority of displaced service workers are Technology has played a complex

at the bottom end of the skill distribution, consistent role in the recent rise

with a movement away from low-skilled tasks in

in offshoring.

which the United States has a comparative disadvan-

tage.

Effects on productivity

Offshoring may enhance productivity growth for sev- Technology has played a complex role in both the

eral reasons. First, offshoring firms can specialize. This recent rise in offshoring and in more generalized

reduces the scope of work done in-house, so firms can productivity gains, making it difficult to isolate the

focus on their core functions. Second, offshoring may effects of ICT within the scope of offshore-induced

accompany business restructuring; the change in the productivity gains. It has been found in the United

composition of the firms labour force and the adop- Kingdom, for example, that plants owned by U.S.-

tion of new best practices may be productivity based multinational firms make better use of ICT than

enhancing. Third, low-cost offshored inputs may free plants owned by other countries multinational firms

up firm resources that can then be invested in produc- (Bloom, Sadun, and Van Reenen 2005). In principle,

tivity-enhancing capital and technology. Finally, some this more effective use of ICT by U.S. affiliates should

tasks may be offshored to more technologically lead to greater productivity growth from their offshor-

advanced firms, allowing final-goods producers to ing activities. Technological improvements and soft-

learn productivity-enhancing production processes ware standardization have also further enhanced

from foreign suppliers. productivity gains from offshoring because they allow

Measuring productivity gains from offshoring is chal- firms to buy services based on advanced technologies

lenging, owing to the so-called self-selection bias. Not without having to incur the sunk costs of acquiring

only is it possible that offshoring improves firms pro- those technologies; Bartel, Lach, and Sicherman (2005)

make this case for outsourcing in general. Finally, it

has been shown that as the price of offshoring-related

18. Service occupations classified as most tradable were those in the follow- ICT falls, firms may invest in more of this technology,

ing sectors: management; business and financial; computer and mathemati- which increases the productivity of workers using it

cal; architecture and engineering; physical and social sciences; legal; and art,

design, and entertainment. (Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg 2006b).

BANK OF CANADA REVIEW AUTUMN 2008 25

Going forward, offshoring of service inputs may have labour in developing countries is still relatively low,

a greater effect on productivity growth than material it is rising rapidly, partly as a result of strong eco-

inputs. Over the past two decades, it is possible that nomic growth that will likely persist for some time

the marginal benefit of material offshoring has declined yet. Third, the ongoing global realignment of

considerably, as firms have long realized its greatest exchange rates could shift the distribution of offshoring

advantages. Given the recent improved affordability activities among countries, with those featuring a

of ICT, however, the offshoring of services is a newer depreciating currency more likely to become a host.20

phenomenon. It thus has much more room to grow, as Finally, changes in some countries environmental

technological frontiers expand and service providers policies could alter a firms decision to offshore.

in host countries develop. The incremental benefits

accrued to service offshoring may therefore be expected

to increase over time.

Offshoring has affected the Canadian

Conclusions economy in much the same way

In summary, the balance of empirical evidence suggests as it has other industrialized

a linkage between improved productivity and off- economies, despite the countrys

shoring. While offshoring has not exerted a noticeable above-average offshoring intensity.

influence on overall employment and earnings growth

in advanced economies, it has likely contributed to a

shift in the demand for labour towards higher-skilled

jobs, although this effect is often difficult to disentangle As the offshoring phenomenon evolves, it may have

from that of technological change and more general ramifications for other branches of economic studies

trade expansion.19 as well. In particular, the potential for rapid expansion

Offshoring has affected the Canadian economy in in the offshoring of services could have profound

much the same way as it has other industrialized effects on how an economy is modelled. Yet, typically,

economies, despite the countrys above-average off- the service sector is assumed to be untradable. Clearly,

shoring intensity. In the case of employment and such an assumption needs to be revisited, and more

wages, this outcome attests to the flexibility and resil- effort should be devoted to designing, monitoring,

ience of Canadas labour market in adjusting to the and analyzing indicators that are suitable for the

challenges of globalization. It could also mean that service sector.

Canadian businesses have taken advantage of the

opportunities presented by a more open world market.

It remains to be seen, however, to what extent a further

diversification of Canadas trading partners away

from the United States to emerging economies would

change this finding.

Continued technological improvements and labour

shortages resulting from population aging in many

industrialized countries could further encourage off-

shoring. At least four factors create some uncertainty

about the future of offshoring, however, particularly

for material inputs. First, if energy prices reach very

high levels, as they have done recently, certain activi-

ties that have been offshored may be brought back

to the home country. Second, although the cost of

19. Many studies cited in this article include offshoring in regressions with-

out controlling for other globalization indicators such as export orientation

and import competition that likely also influence productivity and labour 20. On the other hand, Ekholm, Moxnes, and Ulltveit-Moe (2008) find that

market outcomes. Accounting for these variables appropriately in light of Norwegian exporting firms increased offshoring as a natural hedge against

their high correlation with offshoring could be a challenge. the appreciation of the Norwegian krone in the early 2000s.

26 BANK OF CANADA REVIEW AUTUMN 2008

Literature Cited

Abramovsky, L. and R. Griffith. 2005. Outsourcing Egger, H. and P. Egger, 2005. Labor Market Effects of

and Offshoring of Business Services: How Impor- Outsourcing under Industrial Interdependence.

tant Is ICT? Institute for Fiscal Studies Working International Review of Economics and Finance 14 (3):

Paper No. 05/22. 34963.

Accenture. 2004. Driving High-Performance Out- Ekholm, K., A. Moxnes, and K.-H. Ulltveit-Moe. 2008.

sourcing: Best Practices from the Masters in Con- Manufacturing Restructuring and the Role of

sumer Goods and Retail Services Companies. Real Exchange Rate Shocks: A Firm Level Analy-

Available at <http://www.accenture.com/NR/ sis. Centre for Economic Policy Research Discus-

rdonlyres/C625415D-5E2B-4EDE-9B65- sion Paper No. 6904.

77D635365211/0/driving_outsourcing.pdf>. Feenstra, R. C. and G. H. Hanson. 1996. Globaliza-

Amiti, M. and S.-J. Wei. 2006. Service Offshoring and tion, Outsourcing, and Wage Inequality. National

Productivity: Evidence from the United States. Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working

National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Paper No. 5424.

Working Paper No. 11926. . 1999. The Impact of Outsourcing and High-

Bajpai, N., J. Sachs, R. Arora, and H. Khurana. 2004. Technology Capital on Wages: Estimates for the

Global Services Sourcing: Issues of Cost and United States, 19791990. Quarterly Journal of Eco-

Quality. The Earth Institute at Columbia Univer- nomics 114 (3): 90740.

sity, Center on Globalization and Sustainable . 2003. Global Production Sharing and Rising

Development Working Paper No. 16. Inequality: A Survey of Trade and Wages. In

Baldwin, J. R. and W. Gu. 2008. Outsourcing and Off- Handbook of International Trade, 14685, edited by

shoring in Canada. Statistics Canada Economic E. K. Choi and J. Harrigan. Oxford: Blackwell

Analysis (EA) Research Paper Series No. 055. Publishing.

Baldwin, R. 2006. Globalisation: The Great Unbun- Goldfarb, D. and K. Beckman. 2007. Canadas Chang-

dling(s). Globalisation Challenges for Europe and Fin- ing Role in Global Supply Chains. Conference

land. Available at <http://hei.unige.ch/~baldwin/ Board of Canada Report, March 2007.

PapersBooks/Unbundling_Baldwin_06-09-20.pdf>. Gomez, C. 2005. Offshore Outsourcing of Services

Bartel, A. P., S. Lach, and N. Sicherman. 2005. Out- Not Just a Passing Fad. TD Economics Executive

sourcing and Technological Change. Centre for Summary. Available at <http://www.td.com/

Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper economics/special/outsource05.jsp>.

No. 5082. Gomez, R. and M. Gunderson. 2006. Labour Adjust-

Bhagwati, J., A. Panagariya, and T. N. Srinivasan. ment Implications of Offshoring of Business Serv-

2004. The Muddles over Outsourcing. Journal of ices. In Offshore Outsourcing: Capitalizing on

Economic Perspectives 18 (4): 93114. Lessons Learned: A Conference for Thought Leaders.

Ottawa: Industry Canada.

Bloom, N., R. Sadun, and J. Van Reenen. 2005. It Aint

What You Do, Its the Way You Do I.T. Testing Grossman, G.M. and E. Rossi-Hansberg. 2006a. The

Explanations of Productivity Growth Using U.S. Rise of Offshoring: Its not Wine for Cloth Any-

Affiliates. Available at <http://www.statis- more. In The New Economic Geography: Effects and

tics.gov.uk/articles/nojournal/ Policy Implications, 59102. Proceedings of a con-

sadun_bvr25.pdf>. ference held by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kan-

sas City, Kansas City, MO.

Carney, M. 2008. The Implications of Globalization

for the Economy and Public Policy. Remarks to . 2006b. Trading Tasks: A Simple Theory of

the British Columbia Chamber of Commerce and Offshoring. National Bureau of Economic

the Business Council of British Columbia. Vancou- Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 12721.

ver, BC, 18 February.

BANK OF CANADA REVIEW AUTUMN 2008 27

Literature Cited (Contd)

Hijzen, A. 2003. Fragmentation, Productivity and . 2008. Global Sourcing: Shifting Strategies.

Relative Wages in the UK: A Mandated Wage A Survey of Retail and Consumer Companies.

Approach. GEP Research Paper No. 2003/17. Available at <http://www.pwc.com/extweb/

University of Nottingham, Nottingham. pwcpublications.nsf/docid/

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2007. The Glo- E40FDD13038526A58525745E0070B343/$File/

balization of Labour. In IMF World Economic global-sourcing_2008.pdf>.

Outlook (April): 16192. Washington: International Statistics Canada. 2005. Innovation Survey. See Tang

Monetary Fund. and do Livramento (2008).

Jean, S. and G. Nicoletti. 2002. Product Market Regu- Tang, J. and H. do Livramento. 2008. Offshoring and

lation and Wage Premia in Europe and North Productivity: A Micro-data Analysis. Industry

America: An Empirical Investigation. OECD Canada Working Paper. Forthcoming.

Economics Department Working Paper No. 318.

Trefler, D. 2005. Policy Responses to the New Off-

Jensen, J. B. and L. G. Kletzer. 2005. Tradable Serv- shoring: Think Globally, Invest Locally. Prepared

ices: Understanding the Scope and Impact of Serv- for Industry Canadas Roundtable on Offshoring.

ices Outsourcing. Peterson Institute for Ottawa: Industry Canada.

International Economics Working Paper No. 059.

van Welsum, D. and G. Vickery. 2005. Potential

Kletzer, L. G. 2001. Job Loss from Imports: Measuring the Offshoring of ICT-Intensive Using Occupations.

Costs. Washington: Institute for International Eco- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

nomics. Development. Available at <http://

Kurz, C. J. 2006. Outstanding Outsourcers: A Firm- www.oecd.org/dataoecd/35/11/34682317.pdf>.

and Plant-Level Analysis of Production Sharing. Wessel, D. 2004. The Future of Jobs: New Ones Arise,

Federal Reserve Board Finance and Economics Wage Gap Widens. Wall Street Journal, p. A1,

Discussion Series Paper No. 2006-04. 2 April.

Mann, C. L. 2003. Globalization of IT Services and Yan, B. 2005. Demand for Skills in Canada: The Role

White Collar Jobs: The Next Wave of Productivity of Foreign Outsourcing and Information-Commu-

Growth. Peterson Institute for International Eco- nication Technology. Statistics Canada Economic

nomics, International Economics Policy Briefs Analysis Research Paper No. 035.

No. 0311.

Yuskavage, R. E., E. H. Strassner, and G. W.Medeiros.

Morissette, R. and A. Johnson. 2007. Offshoring and 2008. "Domestic Outsourcing and Imported

Employment in Canada: Some Basic Facts. Statis- Inputs in the U.S. Economy: Insights from Inte-

tics Canada Analytical Studies Research Branch grated Economic Accounts." U.S. Bureau of Eco-

Research Paper Series No. 300. nomic Analysis. Paper prepared for the 2008

Olsen, K. B. 2006. Productivity Impacts of Offshoring World Congress on National Accounts and Eco-

and Outsourcing: A Review. OECD Science, nomic Performance Measures for Nations, Arling-

Technology and Industry Working Paper ton, VA.

No. 2006/1. Yi, K.-M. 2003. Can Vertical Specialization Explain

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Devel- the Growth of World Trade? Journal of Political

opment. 2005. OECD Employment Outlook 2005. Economy 111 (1): 52102.

Washington, D.C.: OECD.

PriceWaterhouseCoopers. 2005. Offshoring in the

Financial Services Industry: Risks and Rewards.

Available at <http://www.pwc.com/extweb/

pwcpublications.nsf/docid/

2711A28073EC82238525706C001EAEC4/$FILE/

offshoring.pdf>.

28 BANK OF CANADA REVIEW AUTUMN 2008

También podría gustarte

- Areo 0415 C 2 PDFDocumento20 páginasAreo 0415 C 2 PDFNehaAún no hay calificaciones

- Benefiting From Export Competitiveness: ConclusionsDocumento6 páginasBenefiting From Export Competitiveness: ConclusionsDarkest DarkAún no hay calificaciones

- Unit 3.5 Notes (ANS)Documento6 páginasUnit 3.5 Notes (ANS)Szeman YipAún no hay calificaciones

- Effects of Current and Capital Account ConvertibilityDocumento4 páginasEffects of Current and Capital Account ConvertibilityNasrin LubnaAún no hay calificaciones

- Is Services Sector Output Overestimated? An Inquiry: R NagarajDocumento6 páginasIs Services Sector Output Overestimated? An Inquiry: R Nagarajsaif09876Aún no hay calificaciones

- Is Services Sector Output OverestimatedDocumento6 páginasIs Services Sector Output Overestimatedapi-3852875Aún no hay calificaciones

- Finals ECONDEVDocumento28 páginasFinals ECONDEVNicolette EspinedaAún no hay calificaciones

- Service Sector Productivity and International CompetitivenessDocumento17 páginasService Sector Productivity and International CompetitivenessvijayrajumAún no hay calificaciones

- International Production: A Decade of Transformation AheadDocumento82 páginasInternational Production: A Decade of Transformation AheadAngel Lopez HzAún no hay calificaciones

- International Production: A Decade of Transformation AheadDocumento60 páginasInternational Production: A Decade of Transformation AheadSunil ChoudhuryAún no hay calificaciones

- Roland Berger Building Industry WinnersDocumento32 páginasRoland Berger Building Industry WinnersbranerAún no hay calificaciones

- Disrupt or Die Transforming Australia S Construction Indus 1667719560Documento16 páginasDisrupt or Die Transforming Australia S Construction Indus 1667719560campoutlineAún no hay calificaciones

- AssignmentDocumento13 páginasAssignmentchathuri50% (2)

- (Finance & Development) Industrial Restructuring in Developing Countries - The Need and The MeansDocumento4 páginas(Finance & Development) Industrial Restructuring in Developing Countries - The Need and The MeansTuong Van PhamAún no hay calificaciones

- Industry FINALDocumento38 páginasIndustry FINALakshatkharcheAún no hay calificaciones

- 111 Struct1Documento8 páginas111 Struct1Tamar LaliashviliAún no hay calificaciones

- Are Global Value Chains Receding The Jury Is Still Out Key 2020 InternatioDocumento18 páginasAre Global Value Chains Receding The Jury Is Still Out Key 2020 InternatioRetno Puspa RiniAún no hay calificaciones

- 2021 Global Powers of ConstructionDocumento46 páginas2021 Global Powers of ConstructionLiora Vanessa DopacioAún no hay calificaciones

- Impact of Trade On Labour Market OutcomesDocumento28 páginasImpact of Trade On Labour Market OutcomesDarya GoryninaAún no hay calificaciones

- Pestel and Scenario Analysis of VW Group (Up2216669)Documento2 páginasPestel and Scenario Analysis of VW Group (Up2216669)junaidmuzamil40Aún no hay calificaciones

- Benefit From Export CompetitivenessDocumento7 páginasBenefit From Export CompetitivenessDarkest DarkAún no hay calificaciones

- Best Practices in MergerDocumento47 páginasBest Practices in MergerAileen ReyesAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 2Documento20 páginasChapter 2bimaka3527Aún no hay calificaciones

- 2011 - Topalova - TRade Liberalization and Firm ProductivityDocumento15 páginas2011 - Topalova - TRade Liberalization and Firm ProductivitychipAún no hay calificaciones

- Market Seller Concentration in PakistanDocumento7 páginasMarket Seller Concentration in PakistanVania ShakeelAún no hay calificaciones

- Globalization: A Force To Economic GrowthDocumento22 páginasGlobalization: A Force To Economic GrowthPeabeeAún no hay calificaciones

- Trade and Theory of Development IGNOUDocumento20 páginasTrade and Theory of Development IGNOUTaranjit BatraAún no hay calificaciones

- 04 Chap1 Gvcdevreport Bprod eDocumento13 páginas04 Chap1 Gvcdevreport Bprod eGervine Scola Mbou LekibiAún no hay calificaciones

- Manufacturing Trends Globalization1Documento15 páginasManufacturing Trends Globalization1Rogers PalamattamAún no hay calificaciones

- Development Unit 3Documento18 páginasDevelopment Unit 3VAIBHAV VERMAAún no hay calificaciones

- Global-Economic-Prospects-June-2021-High Trade CostsDocumento26 páginasGlobal-Economic-Prospects-June-2021-High Trade CostsRonanAún no hay calificaciones

- What Does The Research Say ?: PapersDocumento16 páginasWhat Does The Research Say ?: PaperssercalsaAún no hay calificaciones

- 1Documento21 páginas1Joshua S MjinjaAún no hay calificaciones

- OR MNC ArticleDocumento12 páginasOR MNC ArticleSwaty GuptaAún no hay calificaciones

- Firm DynamicDocumento7 páginasFirm DynamickahramaaAún no hay calificaciones

- 13 International CompetitivenessDocumento7 páginas13 International Competitivenesssaywhat133Aún no hay calificaciones

- Growth of International ProductionDocumento11 páginasGrowth of International ProductionAncyAún no hay calificaciones

- Modelling Local Content RequirementsDocumento18 páginasModelling Local Content RequirementsraedAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 12 - Macroeconomic and Industry AnalysisDocumento8 páginasChapter 12 - Macroeconomic and Industry AnalysisMarwa HassanAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 12 - Macroeconomic and Industry AnalysisDocumento8 páginasChapter 12 - Macroeconomic and Industry AnalysisMarwa HassanAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 12 - Macroeconomic and Industry AnalysisDocumento8 páginasChapter 12 - Macroeconomic and Industry AnalysisMarwa HassanAún no hay calificaciones

- The British Columbia Input-Output Model: What Are Input-Output Models? How Are Input-Output Models Used?Documento3 páginasThe British Columbia Input-Output Model: What Are Input-Output Models? How Are Input-Output Models Used?Giuseppe BurtiniAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 Regional Development Innovation Systems and ServiceDocumento14 páginas1 Regional Development Innovation Systems and ServiceRaoniAún no hay calificaciones

- 1/ The Authors Are Grateful To Willem Buiter, Jonathan Eaton, JacobDocumento42 páginas1/ The Authors Are Grateful To Willem Buiter, Jonathan Eaton, JacobAgni BanerjeeAún no hay calificaciones

- Manufacturing Transformation 130607Documento20 páginasManufacturing Transformation 130607Tanja AshAún no hay calificaciones

- Next-Shoring: A CEO's GuideDocumento11 páginasNext-Shoring: A CEO's GuideRuchi AgrawalAún no hay calificaciones

- McKinsey - Creating Value in Semiconductor IndustryDocumento10 páginasMcKinsey - Creating Value in Semiconductor Industrybrownbag80Aún no hay calificaciones

- Countries by Manufacturing Output Using The Most Recent Known DataDocumento1 páginaCountries by Manufacturing Output Using The Most Recent Known DataGokul KrishAún no hay calificaciones

- Paper 13 PDFDocumento13 páginasPaper 13 PDFDevika ToliaAún no hay calificaciones

- Paper 13 PDFDocumento13 páginasPaper 13 PDFDevika ToliaAún no hay calificaciones

- Central Asian Regional Cooperation and Global Value Chains (George Abonyi, 2007)Documento8 páginasCentral Asian Regional Cooperation and Global Value Chains (George Abonyi, 2007)a2b159802Aún no hay calificaciones

- Big Sten 2016Documento17 páginasBig Sten 2016masresha addisuAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 6 Industrialization and Structural ChangeDocumento44 páginasChapter 6 Industrialization and Structural ChangeJuMakMat Mac100% (1)

- ColombiaDocumento67 páginasColombiaMarco MarksterAún no hay calificaciones

- Is Malaysia Deindustrializing For The Wrong Reasons?Documento3 páginasIs Malaysia Deindustrializing For The Wrong Reasons?fatincameliaAún no hay calificaciones

- The United States Electronics Industry in International TradeDocumento7 páginasThe United States Electronics Industry in International TradeK60 Lê Ngọc Minh KhuêAún no hay calificaciones

- University of International Business and Economics: AssignmentDocumento7 páginasUniversity of International Business and Economics: AssignmentNabeel Safdar100% (1)

- Globalize or Customize: Finding The Right Balance: Global Steel 2015-2016Documento32 páginasGlobalize or Customize: Finding The Right Balance: Global Steel 2015-2016Aswin Lorenzo GultomAún no hay calificaciones

- CRH Case & QuestionDocumento9 páginasCRH Case & QuestionStariun0% (2)

- Distributional Consequences of Direct Foreign InvestmentDe EverandDistributional Consequences of Direct Foreign InvestmentAún no hay calificaciones

- Accounting and Disclosure of Football Player RegistrationsDocumento63 páginasAccounting and Disclosure of Football Player RegistrationsosefresistanceAún no hay calificaciones

- Wa0001Documento3 páginasWa0001osefresistanceAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 - F. RobertDocumento78 páginas1 - F. RobertosefresistanceAún no hay calificaciones

- Corrigee Td3 CAE-1Documento5 páginasCorrigee Td3 CAE-1osefresistanceAún no hay calificaciones

- Offshoring (Or Offshore Outsourcing) and Job Loss Among U.S. WorkersDocumento12 páginasOffshoring (Or Offshore Outsourcing) and Job Loss Among U.S. WorkersosefresistanceAún no hay calificaciones

- Offshore Outsourcing and Productivity: Preliminary and Incomplete. Please Do Not QuoteDocumento28 páginasOffshore Outsourcing and Productivity: Preliminary and Incomplete. Please Do Not QuoteosefresistanceAún no hay calificaciones

- Offshoring: Threats and OpportunitiesDocumento33 páginasOffshoring: Threats and OpportunitiesosefresistanceAún no hay calificaciones

- The Manuals Com Cost Accounting by Matz and Usry 9th Edition Manual Ht4Documento2 páginasThe Manuals Com Cost Accounting by Matz and Usry 9th Edition Manual Ht4ammarhashmi198633% (12)

- Ds Lm5006 en Co 79839 Float Level SwitchDocumento7 páginasDs Lm5006 en Co 79839 Float Level SwitchRiski AdiAún no hay calificaciones

- Contact List For All NWGDocumento22 páginasContact List For All NWGKarthickAún no hay calificaciones

- G M CryocoolerDocumento22 páginasG M CryocoolerJaydeep PonkiyaAún no hay calificaciones

- Fiesta Mk6 EnglishDocumento193 páginasFiesta Mk6 EnglishStoicaAlexandru100% (2)

- Lab 11 12 ECA HIGH AND LOW PASSDocumento32 páginasLab 11 12 ECA HIGH AND LOW PASSAmna EjazAún no hay calificaciones

- Non Domestic Building Services Compliance GuideDocumento76 páginasNon Domestic Building Services Compliance GuideZoe MarinescuAún no hay calificaciones

- Tiger SharkDocumento2 páginasTiger Sharkstefanpl94Aún no hay calificaciones

- MKDM Gyan KoshDocumento17 páginasMKDM Gyan KoshSatwik PandaAún no hay calificaciones

- Nyuszi SzabásmintaDocumento3 páginasNyuszi SzabásmintaKata Mihályfi100% (1)

- Differences Between Huawei ATCA-Based and CPCI-Based SoftSwitches ISSUE2.0Documento46 páginasDifferences Between Huawei ATCA-Based and CPCI-Based SoftSwitches ISSUE2.0Syed Tassadaq100% (3)

- TDS - Masterkure 106Documento2 páginasTDS - Masterkure 106Venkata RaoAún no hay calificaciones

- Competitive Products Cross-Reference GuideDocumento30 páginasCompetitive Products Cross-Reference GuideJeremias UtreraAún no hay calificaciones

- Workshop Manual Group 21-26 - 7745282 PDFDocumento228 páginasWorkshop Manual Group 21-26 - 7745282 PDFabdelhadi houssinAún no hay calificaciones

- Questions Supplychain RegalDocumento2 páginasQuestions Supplychain RegalArikuntoPadmadewaAún no hay calificaciones

- Darcy Friction Loss Calculator For Pipes, Fittings & Valves: Given DataDocumento2 páginasDarcy Friction Loss Calculator For Pipes, Fittings & Valves: Given DataMSAún no hay calificaciones

- 7GCBC PohDocumento75 páginas7GCBC PohEyal Nevo100% (1)

- Using Gelatin For Moulds and ProstheticsDocumento16 páginasUsing Gelatin For Moulds and Prostheticsrwong1231100% (1)

- Thrust Bearing Design GuideDocumento56 páginasThrust Bearing Design Guidebladimir moraAún no hay calificaciones

- Literature Study Nift ChennaiDocumento5 páginasLiterature Study Nift ChennaiAnkur SrivastavaAún no hay calificaciones

- C9 Game Guide For VIPsDocumento62 páginasC9 Game Guide For VIPsChrystyanoAún no hay calificaciones

- Sell Sheet Full - Size-FinalDocumento2 páginasSell Sheet Full - Size-FinalTito BustamanteAún no hay calificaciones

- Vsphere Esxi Vcenter Server 50 Monitoring Performance GuideDocumento86 páginasVsphere Esxi Vcenter Server 50 Monitoring Performance GuideZeno JegamAún no hay calificaciones

- Denr Administrative Order (Dao) 2013-22: (Chapters 6 & 8)Documento24 páginasDenr Administrative Order (Dao) 2013-22: (Chapters 6 & 8)Karen Feyt Mallari100% (1)

- Manual Instructions For Using Biometric DevicesDocumento6 páginasManual Instructions For Using Biometric DevicesramunagatiAún no hay calificaciones

- GTGDocumento4 páginasGTGSANDEEP SRIVASTAVAAún no hay calificaciones

- Filtration 2Documento5 páginasFiltration 2Ramon Dela CruzAún no hay calificaciones

- Brahmss Pianos and The Performance of His Late Works PDFDocumento16 páginasBrahmss Pianos and The Performance of His Late Works PDFllukaspAún no hay calificaciones

- EN - 61558 - 2 - 4 (Standards)Documento12 páginasEN - 61558 - 2 - 4 (Standards)RAM PRAKASHAún no hay calificaciones

- PS User Security SetupDocumento30 páginasPS User Security Setupabhi10augAún no hay calificaciones