Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Final

Final

Cargado por

api-3377007230 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

54 vistas25 páginasThis document summarizes a research paper that assesses the effect of two aspects of education on political development in lesser-developed countries. It analyzes the effect of civic education programs and the level of general education. It summarizes three studies on civic education programs - one in Argentina that used newspapers in schools, one in South Africa called "Democracy for All", and found they increased students' political knowledge, tolerance and support for democratic values and institutions. The level of education is also likely to impact political development factors like participation, support for democracy and political knowledge.

Descripción original:

Título original

final

Derechos de autor

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoThis document summarizes a research paper that assesses the effect of two aspects of education on political development in lesser-developed countries. It analyzes the effect of civic education programs and the level of general education. It summarizes three studies on civic education programs - one in Argentina that used newspapers in schools, one in South Africa called "Democracy for All", and found they increased students' political knowledge, tolerance and support for democratic values and institutions. The level of education is also likely to impact political development factors like participation, support for democracy and political knowledge.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

0 calificaciones0% encontró este documento útil (0 votos)

54 vistas25 páginasFinal

Final

Cargado por

api-337700723This document summarizes a research paper that assesses the effect of two aspects of education on political development in lesser-developed countries. It analyzes the effect of civic education programs and the level of general education. It summarizes three studies on civic education programs - one in Argentina that used newspapers in schools, one in South Africa called "Democracy for All", and found they increased students' political knowledge, tolerance and support for democratic values and institutions. The level of education is also likely to impact political development factors like participation, support for democracy and political knowledge.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponibles

Descargue como PDF, TXT o lea en línea desde Scribd

Está en la página 1de 25

Running head: THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

The Effect of Education on Political Development

Aaron Carlson

Minnesota State University Moorhead

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

The Effect of Education on Political Development

This paper assesses the effect of two aspects of education on the political

development of lesser-developed countries. It begins by analyzing the effect of civic

education programs on the development of newly emerging democracies, and proceeds to

assess the effect of level of education on various political development factors.

It is worth noting that this analysis employs a political definition of development

rather than an economic one. It defines a developed country as a stable functioning

democracy that holds open democratic elections, is widely supported and participated in

by an informed electorate, and upholds democratic principles such as free speech,

freedom of religion, and equality under the law. Thus, development constitutes any gain

made to such desirable political factors as participation in the democratic process, support

for democratic attitudes and values, identification with the nation as opposed to the tribe

or ethnic group, and general political knowledge and skills among the electorate.

Economic factors are outside the scope of this analysis. It is the aim of this paper to

assess the direct effect of civic education programs and level of education on the

development of a mature democratic political culture in newly emerging democracies,

separate from economic concerns.

Civic Education and Development

It is well established that the effectiveness of a democratic state hinges to a

significant extent upon its possession of legitimacy. The citizenry must believe in its

governments responsiveness, openness, and general positive intent in order to want to

participate. History demonstrates that without legitimacy, states tend to fester with

discontent and ill will, become ineffective, unstable, and potentially revolutionary. An

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

effective democratic state also requires an informed electorate, which is equipped with

the skills and knowledge required to participate in democratic processes and institutions.

In the absence of an informed electorate, incompetent leaders may be elected, effective

parties may not gain the support they require to flourish, narrow interest groups may be

allowed to gain unhealthy levels of power, and government will stand little chance of

growing into a mature functioning democracy. The question this raises is what can be

done to promote participation in functioning democratic regimes, encourage support for

democratic ideals, and increase knowledge and political skills among the electorate in

newly developing democracies. One potential answer is the instituting of civic education

programs, the goal of which would be to disseminate information and ideas that would

lead to political development in these areas.

Such civic education programs are abundant in lesser-developed countries, and a

significant body of research exists that assesses their effectiveness (Finkel & Ernst,

2005). Three such assessments are reviewed here. The studies were chosen to represent

the range of civic education programs that have been instituted throughout the third

world. Two of the studies assess African civic education programs, while the third study

assesses a program implemented in South America. Each of the three studies focuses its

analysis on a different age group, and examines different factors related to civic

education and political development. It is believed that these three studies provide a

representative sample of civic education programs instituted throughout newly emerging

democracies, and enable an accurate analysis of the effect of such programs on the

political development of third world countries.

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

Bell, Catterberg, Morduchowicz, and Niemi (1996) conduct an assessment of

Newspapers in the Schools, an Argentine civic education program implemented in

1987. The goal of the program is to bring civic material to six and seventh graders in a

way that promotes political knowledge, political tolerance, and open political discussion.

As of 1996, 40,000 teachers had received training from one of the programs regional

workshops, and 125,000 students had participated in the program (Bell et al., 1996).

Newspapers in the Schools has a somewhat novel structure, which differs from a

typical government or social studies class, and also differs from the structure of the other

two programs assessed here. The program uses newspapers rather than textbooks, and

teacher-led classroom discussions based on the newspaper readings, rather than a lecture

based pedagogical method (Bell et al., 1996). Newspapers in the Schools also makes

use of different newspapers with competing viewpoints, and teachers are trained to

encourage students to express conflicting opinions and controversial ideas in discussion

(Bell et al., 1996).

Bell et al. (1996) obtain their results using data from a paper and pencil

questionnaire administered to 4,000 Argentine students, half of whom participated in the

Newspapers in the Schools program, and half of whom did not and serve as a control

group. The authors match the two groups for demographic factors and control for various

variables such as prior political interest and media exposure. They then measure the

effect of the program on students factual political knowledge, political tolerance, and

democratic attitudes. Results for engagement and participation are not applicable due to

the young age of the demographic (Bell et al., 1996).

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

The results of the study are conclusive and find that students who participate in

the program are more politically knowledgeable and have attitudes that are more

supportive of democratic ideas than the control group (Bell et al., 1996). The authors find

the greatest gains to be made in factual political knowledge. The magnitude of the

programs effect in this area is sufficient to be considered highly successful by the

authors, particularly given that students participate in the Newspapers in the Schools

program once a week. Students who participated in the program are found to more often

give a correct answer than control group students to every one of the six factual questions

asked, with increases ranging from 5 to 12 percentage points over the control group. 11.5

percent more program students than control group students were able to name an

Argentine public service that was privatized, and 12.4 percent more were able to name a

country in Europe where there is a war (Bell et al., 1996).

Bell et al. (1996) note that factual knowledge is a necessary but not sufficient

condition for mature political culture, and go on to assess the programs effect on

political tolerance and support for democratic ideas. The program is found to cause less

significant but still conclusive gains in these areas. 6.8 percent more program students

than control students expressed support for freedom of religion, 6.3 percent more

indicated that they would, Oppose a bad government project, and 2.7 percent more

agreed with the statement, All right for women to work (Bell et al., 1996).

Bell et al. (1996) conclude that civic education programs have an effect on the

knowledge and attitudes of pre-adults. Students who took part in the program are found

to uniformly possess greater factual knowledge than those who did not, and have attitudes

more indicative of a democratic orientation (Bell et al., 1996).

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

Finkel and Ernst (2005) perform an assessment of Democracy for All, a South

African civic education program implemented in the early 1990s. The program sends

trained university students into South African high schools to teach 16,000 eleventh and

twelfth graders per year about issues related to democracy, human rights, elections,

conflict resolution, and how citizens can participate responsibly in democratic politics

(Finkel & Ernst, 2005). The frequency with which participating students attend the

program varies across schools, with classes being taught a minimum of once a week and

a maximum of once a day. Teachers are encouraged to use active teaching methods in the

classroom, such as group discussions, role playing exercises, field trips, and mock trials,

though the extent to which such methods are employed varies by teacher (Finkel & Ernst,

2005).

Finkel and Ernst (2005) use data gleaned from a survey administered to 600 South

African high school students, 385 of whom participated in either the Democracy for All

program or their normal school-instituted civic education programs, and 215 of whom

had no formal civic education exposure. The three groups are controlled for demographic

factors, family political background, media exposure, and prior political interest, and

measured on political knowledge, civic duty, tolerance, institutional trust, civic skills, and

approval of legal forms of political participation. Independent variables related to the

program include frequency of instruction, teacher quality, and activity of teaching

methods (Finkel & Ernst, 2005).

The results of the research align with those of Bell et al. (1996). The authors find

that the program most significantly affects political knowledge, with Democracy for

All students who received daily instruction providing an average of 10 percent more

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

correct answers to factual questions than control group students. The authors note that the

magnitude of this increase is twice that of a study conducted by Niemi and Junn (1998) in

the United States, which seems to indicate that civic education programs may have a

more significant effect on political knowledge in lesser developed countries, where the

messages received through civic education are less likely to be redundant (Finkel &

Ernst, 2005). Finkel and Ernst (2005) also find that there is no difference in political

knowledge between students receiving Democracy for All training and civic education

training in their normal classrooms. Rather, the variable that causes increases in political

knowledge is frequency of civic education of any kind.

Finkel and Ernst (2005) go on to assess the programs effect on attitude, value,

and behavioral change, and find that frequency of civic education exposure has no effect

on these variables. Students who underwent daily civic education training are found to be

no more politically tolerant, trusting of government institutions, or skillful civically than

students who underwent training only once a week. Two factors are found to have a

significant bearing upon the success of change in these areas: teacher likability, and

activity and openness of teaching methods (Finkel & Ernst, 2005). The authors theorize

that the mechanism underlying this phenomenon is one rooted in social psychology

research, which suggests that a significant source of attitude change is role-playing

behavior. Activities such as mock trials, field trips, and group debates increase student

participation in role-playing behavior, particularly when aided by a likeable and credible

teacher, and thus, lead to greater attitude change (Finkel & Ernst, 2005). The research

indicates that in the absence of both credible, likeable teachers and open, activity-based

teaching methods, negligible effects were made on student attitude or behavioral change.

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

With the presence of both credible, likeable teachers, and open, activity-based teaching

methods, modest, but significant changes were made to student attitudes, values, and

sense of civic duty, with results being higher than those of Bell et al. (1996).

Finkel and Ernst (2005) conclude that civic education has a significant impact on

factual political knowledge and relatively weaker effects on democratic values, skills, and

participatory orientations. Changes in these areas are not caused by giving students more

civic education. Rather, change in these areas is best accomplished when credible,

likeable teachers lead students in activities that encourage role-playing behavior. When

these beneficial pedagogical conditions are met, civic education has the potential to cause

gains in political knowledge, political skills, and democratic values among students in

newly emerging democracies (Finkel & Ernst, 2005).

Finkel and Smith (2011) assess the effectiveness of the Kenyan National Civic

Education Program, a major Kenyan initiative implemented during the run-up to Kenyas

2002 democratic election. The program consisted of 50,000 workshops, lectures, plays,

and puppet shows aimed at promoting civic skills, democratic values, and engagement in

the democratic regime among adult Kenyan citizens. 4.5 million Kenyans participated in

the program, which amounts 15 percent of the total population of Kenya, and the program

affected almost half of all Kenyan citizens either directly or indirectly through discussion

with participants (Finkel & Smith, 2011).

One of the questions Finkel and Smith (2011) raise is whether or not such

programs can disseminate democratic skills and orientations among an electorate in the

short term. They note that it has long been thought that the acquisition of such skills and

orientations would be a long-term process for citizens of newly developing democracies,

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

which would occur along with social modernization and generational replacement (Finkel

& Smith, 2011). Kenyas 2002 elections raised the question of what could be done to

enhance democratic political culture in the year or so leading up to the election. Finkel

and Smiths (2011) results suggest that such short-term acquisition of democratic skills

and orientations can be aided by civic education programs, and provide the most

significant evidence of the three studies reviewed that civic education aids political

development (Finkel & Smith, 2011).

Finkel and Smith (2011) gauge the effect of the Kenyan National Civic Education

Program on participants using a longitudinal design, with data being taken from three

waves of interviews. They also gauge the indirect effects of the program on Kenyan

society at large through the use of questions relating to political discussion among both

participants and non-participants in the program. The studys dependent variables are

political knowledge, participation, tolerance, and sense of national versus tribal

identification. Knowledge is measured using four factual questions related to Kenyan

politics. Participation is measured by asking subjects whether they had worked for a

political party or candidate, participated in community problem solving efforts, attended

a local council meeting, met with government officials, contacted a local or national

official, protested, marched on issue, or contacted local chief or traditional leader (Finkel

& Smith, 2011). Tolerance is gauged by asking subjects whether certain people should be

allowed to speak or stage a peaceful protest. Ethnic or tribal versus national identification

is assessed by asking subjects, How important is being Kenyan? and, How important

is being member of your tribe or ethnic group? (Finkel & Smith, 2011). These factors

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

are then measured both as they are affected by direct exposure to the National Civic

Education Program, and as they are affected by post-program discussion.

The results for effects on political knowledge align with those of Bell et al. (1996)

and Finkel and Ernst (2005), with participants in the National Civic Education Program

giving correct answers to 12 percent more factual political questions than non

participants. The findings for effects on political tolerance and national versus tribal

identification are also conclusive, and are more significant than the two studies

previously reviewed. Finkel and Smith (2011) find that only political participation is not

significantly affected by civic education when compared to other factors, such as group

membership and political interest. The authors note that this may be due the programs

lack of direct appeals to increase participationthe program encouraged participants to

vote, but little beyond that. Finkel and Smith (2011) view these results as strong evidence

that adult civic education programs are able to affect orientations relevant to democratic

political culture. Finkel and Smith (2011) also find that gains to political knowledge were

greatest among individuals with the lowest levels of education, and that increases in

tolerance and national versus tribal identification were twice as significant for rural

individuals than urban. Thus, the programs effects seem to have been concentrated

among those who needed them the most (Finkel & Smith, 2011).

Findings for post-program discussion effects are also conclusive. This is to be

expected, as a large body of literature suggests that political discussion has an effect on

political development factors. Delli Carpini and Keeter (1996) and Eveland, Hayes, Shah,

and Kwak (2005), find that political discussion promotes general political knowledge.

Mutz (2006) finds that political discussion increases political tolerance and awareness of

10

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

the reasons behind others views. Gibson (2001) finds that political discussion increases

support for democratic institutions and processes. And Lake and Huckfeldt (1998) find

that political discussion increases political participation. Based on such research, Finkel

and Smith (2011) theorize that civic education may lead to more political discussion,

which should in turn lead to further increases in political knowledge, participation, and

democratic orientations. Finkel and Smiths (2011) data substantiates their hypothesis.

They find that over half of all people who participated directly in the National Civic

Education Program discussed workshop experiences with at least three other individuals,

and that individuals who participated in the program were also likely to discuss the

experiences of other participants in the program. This led to 25 percent of all non-NCEP

treated individuals discussing the NCEP experiences of three or more people who had

participated in the program, and 40 percent of control group individuals discussing the

civic education experiences of at least one participant. Thus, the program affected more

individuals who did not participate in the National Civic Education Program than it did

participants. These results are significant considering that discussion affects political

development factors. Finkel and Smith (2011) find that discussing workshop experiences

with three or more people has a greater effect on knowledge, tolerance, and national

identification than attending only one workshop and not engaging in discussion. In light

of how many individuals were indirectly affected by the program, Finkel and Smith

(2011) posit that discussion likely produced more democratic change than direct program

exposure.

Finkel and Smith (2011) conclude that between 40 and 50 percent of all Kenyan

citizens were exposed either directly or indirectly to the messages transmitted by the

11

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

National Civic Education Program during the run-up to the 2002 democratic elections,

which led to increases in political knowledge, tolerance, national versus tribal

identification, and participation throughout the country. The program disproportionately

benefited those who were disadvantaged in education and social resources, and caused

significant post-program discussion, which led to secondary effects that were equal in

magnitude, if not larger in magnitude than the effects of direct exposure. Finkel and

Smith (2011) believe that their results suggest that the potential impact of adult civic

education on strengthening democratic political culture in transition societies is far

beyond what had previously been estimated.

Research producing similar results abounds. Finkel (2002) finds that adults in

nine programs in the Dominican Republic, Poland and South Africa were nearly twice as

likely as control group individuals to attend municipal meetings or participate in

community problem solving activities. In developed countries, studies such as Niemi and

Junns (1998) find that civic education programs bring about somewhat smaller, but still

significant increases in knowledge, participation, and tolerance. Particularly when civic

education programs are taught by likeable, credible teachers, and using open activity

based pedagogical methods, civic education programs have the potential to cause

increases in political knowledge, democratic attitudes, and political engagement, and

ultimately fuel political development in third world countries.

Level of Education and Political Development

Civic education programs with the specific goal of increasing political

knowledge, participation, tolerance, and democratic attitudes succeed in their aims. The

second question addressed here is the effect of years of general education on similar

12

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

factors, with a particular emphasis on participation. One of the most well documented

relationships in education and political science literature is the positive correlation

between years of education and political participation (Meyer & Rubinson, 1975). More

highly educated people are more likely to vote, to participate in campaigns, to attend

meetings, and to contact government officials. Years of education is in many cases the

single best predictor of an individuals engagement with the political system, level of

political tolerance, and adherence to democratic political attitudes (Meyer & Rubinson,

1975). One question this relationship begs is whether the content of education directly

causes these gains, or whether such gains are caused by a confounding variable. It is a

practical policy question if the goal is political development. If education raises absolute

levels of political participation and enlightenment, measures should be taken to keep

students in school and send more students to attend college, as this would raise a

societys absolute level of political engagement and enlightenment. If education is shown

not to cause such gains, then money would better be invested in other institutions and

processes that could better raise levels of political participation, knowledge, and

tolerance.

Hillygus (2005) identifies three diverging explanations for the positive correlation

between level of education and desirable political factors such as political participation

and knowledge. The first is the Civic Education Hypothesis, which posits that the

observed increases in desirable political factors that correspond with rising levels of

education are caused by the content of the education itself. Social studies and political

science courses provide students with the knowledge required to participate in democratic

processes, and language courses provide students with the verbal skills required to

13

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

communicate political ideas, research political candidates and parties, and follow current

events (Hillygus, 2005). The second hypothesis Hillygus identifies is the Social

Network Hypothesis, which points out that if the Civic Education Hypothesis is

correct, then increasing levels of education should lead to a corresponding increase in

levels of political participation. Yet this has been shown not to be the case in some

developed countries. The United States, for example, has experienced dramatic increases

in educational attainment over the past fifty years, and a simultaneous decrease in

political engagement (Hillygus, 2005). The Social Network Hypothesis explains this

observation by concluding that it is not the content of education that increases political

engagement. Rather, increased education confers social status, which leads to social

network centrality, and social network centrality is the largest cause of political

participation. Thus, political participation can only occur through winning a zero-sum

competition for social status, and education helps people win. This implies that more

education does not mean more people will participate, but rather that more education will

make participating more difficult, by requiring individuals to attain higher educational

status if they want to participate (Hillygus, 2005). The third hypothesis identified by

Hillygus (2005) is what he calls the Political Meritocracy Hypothesis, which proposes

that democratic enlightenment and political participation are correlated with educational

attainment, but not caused by it. Rather, both are caused a confounding variable, namely,

intelligence. Intelligence produces both educational attainment and high levels of

political participation and knowledge, and education can do little to increase either innate

intelligence or political development.

14

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

Numerous studies assessing the relationship between educational attainment and

political enlightenment and participation have been conducted in the United States. Such

studies have produced contradictory results. Four such studies are briefly reviewed here,

with the goal of laying a theoretical groundwork. Following this, three studies using data

from developing countries are reviewed, each of which looks at education and political

development on a different continent. It is believed that such a review will provide the

information necessary to accurately assess the relationship between level of education

and political development in lesser-developed countries.

Nie, Junn, and Stehlik-Barrys 1996 book, Education and Democratic Citizenship

in America is the leading study that supports the Social Network Hypothesis, which

suggests that education does not cause increases in political participation by bestowing

necessary knowledge and skills. Rather, education is a sorting mechanism, which gives

people access to politics by giving them social status and social network centrality (Nie et

al., 1996). Nie et al. (1996) look at the 1990 United States Citizen Participation Survey

and analyze the effect of education on two separate variables: democratic enlightenment,

which consists of political knowledge and values, and political participation, which

includes voting, working on a political campaign, protesting, etc. Nie et al.s (1996)

results suggest that democratic enlightenment is primarily influenced by cognitive

proficiency, with verbal skills being particularly important. Thus, they conclude that

democratic enlightenment is to an extent determined by innate intelligence, but that

education can also have a net positive effect on democratic enlightenment by increasing

verbal skills and transmitting political knowledge and ideas (Nie et al., 1996). Less

optimistically, Nie et al. (1996) conclude that education can do little to increase net

15

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

political participation, as political access for new groups always means less access for

others (Nie et al., 1996). Increased education levels will not lead to net increases in

political participation due to the limited capacity of political elites to respond to demands.

Rather, increased educational attainment will merely lead political power holders to make

more fine-grained decisions in regards to who deserves their attention (Nie et al.,1996).

Berinsky and Lenz (2011) obtain results that substantiate Nie et al.s claims. They

begin their argument by pointing to the marked increase in educational attainment that

has occurred in the United States over the past sixty years, and the simultaneous drop in

levels of political participation. They hypothesize that education is less a measure of

ones civic skills than it is an index of status in society, cognitive skills, and personality

traits that leads to civic engagement (Berinsky & Lenz, 2011). The authors proceed to

summarize two studies that suggest opposing conclusions. The first study tracks

individuals who participated in three studies designed to increase high school graduation

rates, and finds that in all three studies, exogenously induced changes in high school

graduation rates led to higher voter turnout. The second study explores the effect of

variation in compulsory education laws, and proximity from an individuals high school

to a 2-year community college, and concludes that educational attainment has a large and

significant impact on levels of engagement. When compulsory education laws require

students to stay in school longer, students are more likely to go on to vote, and when

students live closer to a 2-year community college, and are therefore more likely to attend

some college, they are similarly more likely to vote. Berinsky and Lenz (2011) do not

present an explanation for why the results of these studies differ from their own, and go

on to present their results. Berinsky and Lenz (2011) find that Vietnam War-era men who

16

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

had some college voted 19 percent more than men with no college, without controlling

for variables, but that when variables such as prior political interest are controlled for, the

estimation for the effect of education itself is 6 to 8 percent. This data causes Berinksy

and Lenz (2011) to conclude that education itself has little reliable causal effect on voter

turnout.

Hillygus (2005) assesses a set of data gleaned from the Baccalaureate and Beyond

Longitudinal study, a study that looks at the political participation of American college

students, and finds the civic education hypothesis to be best supported by the data. He

finds that future political participation and enlightenment is related to social science

curriculums in colleges, as well as verbal SAT scores, which suggests that the content of

higher education itself causes increased political participation by increasing verbal skills

and political knowledge. Social Science curriculums, with their emphasis on politics and

history, and language courses, with their emphasis on improving verbal skills, provide

students with the knowledge and skills they need to participate in democratic processes

(Hillygus, 2005).

Campbell (2009) responds to the work of Nie et al. (1996). He begins by

hypothesizing that the claims of Nie et al. (1996) overestimate the extent to which

political participation is competitive. Nie et al. (1996) argue that all forms of political

engagement, including campaign activity, voting, political attentiveness, knowledge of

candidates, and even membership in voluntary organizations, are zero-sum games,

bounded by finite resources and conflict, where ones gain will necessarily be anothers

loss. Campbell (2009) argues that group membership, voting, and expressive activities

such as protesting and signing petitions, should not driven by a zero-sum competition

17

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

over social position, and that the only aspect of participation that should be driven by

competition to a significant extent is electoral activity, which he defines as membership

in political campaigns. Campbell (2009) performs his analysis using data from the 2002

National Civic Engagement Study, and concurs with Nie et al. (1996) that electoral

activity is bounded. His results suggest that participation in political campaigns is largely

dictated by social status, and that the relative nature of social status prevents net gains in

levels of electoral activity from occurring. Campbells (2011) results also align with Nie

et al.s in regards to educations effect on democratic enlightenment. In contrast to

participation in electoral activities, where increased education makes it more difficult for

an individual to participate, democratic enlightenment is universally increased by gains in

educational attainment. Campbell (2011) diverges from Nie et al. in his estimation of the

extent to which voting, group membership, and expressive activities such as protesting

are bounded. His regression analysis of the National Civic Engagement Study data

indicates that increased education causes absolute increases in group membership and

expressive political activities.

The American studies reviewed agree that more education leads to increased

levels of democratic enlightenment, but do not come to a consensus on the precise effect

of increased education on political participation. Nie et al. argue that the majority of

forms of political participation are bounded and competitive, and that net levels of

political participation cannot be increased by increasing levels of education. Campbell

(2011) argues that only participation in campaign activities is a zero-sum game that

cannot be increased by education. Now that a theoretical groundwork has been laid, three

18

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

studies that have been conducted in the third world will be reviewed, and an attempt will

be made to gauge which theory applies to lesser-developed countries.

Syal (2012) looks at the effect of level of education on political development

factors in India, and finds, through a statistical analysis of data gleaned from the 2004

National Election Studies, that increases in education levels cause increased political

participation and interest. Indian citizens have experienced increasing education levels

and literacy rates throughout the 1990s and 2000s, and these gains correspond with

increases in political participation and political interest, particularly in economically

depressed sectors of society. Syals (2012) regression analysis suggests that the

relationship is causal in nature. She finds that 27 percent of Indian citizens who have no

formal education express an interest in politics, 50 percent with a middle school

education express an interest in politics, and 62 percent of Indians with post-graduate or

professional degrees express an interest in politics. Similarly, she finds that 22 percent of

uneducated Indian citizens participate in electoral activities, 37 percent of Indians with a

middle school education participate in electoral activities, and 40 percent of Indians with

at least some college participate in Indian electoral activities. Syal (2012) controls for

demographic factors such as family income and media exposure, and suggests that more

education has increased absolute levels of political interest and participation in India,

primarily through providing citizens with verbal skills and political knowledge, which are

in turn tools that Indian citizens use to understand and participate in politics (Syal, 2012).

Klesner (2007) looks at the effect of various forms of social capital, including

education, on political engagement in Argentina, Chile, Mexico, and Peru, and finds that

social capital, especially in the form of nonpolitical organizational involvement and

19

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

volunteering, promotes political participation in Latin America. While this seems to

substantiate the Social Network Hypothesis, which suggests that social capital is the

primary predictor of political participation, Klesner (2007) goes on to note that,

Education and subjective political engagement, measured by levels of interest in politics

and the sense that politics is important, also matter, maybe every bit as much as social

capital (Klesner, 2007, p. 27). Klesner obtains data for the effect size of having had at

least some exposure to higher education on various forms of participation such as signing

a petition, volunteering for a party, and participating in a lawful demonstration, and finds

that it is greater than the effect sizes for other social capital factors such as spending time

socializing with friends, participating in a labor union, or being a member of a church or

professional organization. Klesners (2007) results suggest that while social capital and

social network centrality play a part in determining political participation in the four

Latin American countries studied, education plays a large part as well. Education seems

to have its positive effect on participation in Latin America not only by conferring social

capital, but also by providing individuals with other factorslikely verbal skills and

political knowledgethat enable them to better participate.

Kuenzi (2006) looks at both formal and informal education in rural Senegal, and

obtains results for formal education that are similar to Syals (2012), with increased

formal education causing increased electoral and community participation. Even more

significant are the effects of additional years of non-formal education, or education that is

not government led, but rather instituted by NGOs, with specific educational goals aimed

at specific groups. Kuenzi (2006) assesses four such programs, none of which are directly

aimed at increasing civic participation or political knowledge. Rather, they are

20

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

implemented with the primary goal of increasing literacy among rural Senegalese

villagers. It is found that each year of education in these nonformal education programs

increases participants community leadership, community participation, and the

likelihood that they will vote and contact a government official. 51 percent of rural

Senegalese villagers who received 0 years of non-formal education voted in the 2000

Senegalese election, 60 percent who received 1 to 2 years of non-formal education voted,

and 66 percent who received 2 to 3 years voted. Similarly, 8 percent of rural Senegalese

individuals with 0 years of non-formal education exhibited high levels of community

participation, 22 percent of those with 1 to 2 years of non-formal education exhibited

high levels of community participation, and 35 percent of those with 2 to 3 years

exhibited high levels of community participation (Kuenzi, 2006). These numbers are

obtained controlling for confounding variables such as prior political engagement and

media exposure, and a causal mechanism, as opposed to a proxy or social network

mechanism is hypothesized. Similar to the other studies of lesser-developed countries, the

results indicate that the effects of education are absolute, and that the content of the

education increases citizens ability to participate, primarily by increasing their verbal

skills and political knowledge. Kuenzi (2006) also notes that the effects are concentrated

among those with the lowest levels of formal education and social capital, and women,

who, the author notes, are often excluded from the formal education process.

A review of the literature suggests that education plays a different role in

developed and lesser-developed countries. In the American studies reviewed, there is

debate as to whether the content of education causes increased participation through

providing political knowledge and verbal skills, or whether education merely confers

21

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

social status. In the third world studies reviewed, there is little debate; the civic education

hypothesis applies. Increased educational attainment in lesser-developed countries causes

pronounced net gains in political interest and participation, particularly among those with

the lowest levels of social capital, and it is hypothesized that education is accomplishing

this by improving verbal skills and providing political knowledge, which leads

individuals to develop an interest in politics, better understand political ideas, and

ultimately, participate in political processes.

Conclusions

Both civic education programs and level of education affect political

development. Civic education programs in newly emerging democracies increase

individuals levels of political knowledge, political participation, adherence to democratic

attitudes, and national versus tribal identification. Additionally, more general education

causes gains to be made in similar areas by increasing verbal skills and political

knowledge. The conclusion to be drawn from this is that civic education programs and

increased levels of education promote political development in lesser-developed

countries by providing citizens with the skills and knowledge required to participate and

function in a democratic society. It is clear that education can be a vital tool for

democratization and political development.

22

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

References

Arnove, R. (1973). Education and political participation in rural areas of Latin

America. Comparative Education Review, 17(2), 198-215.

Bell, F., Catterberg, E., Morduchowicz, R., & Niemi, R. (1996). Teaching political

information and democratic values in a new democracy: An Argentine experiment.

Comparative Politics, 28(4), 465-476. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/422053

Berinsky, A. J., & Lenz, G. S. (2011) Education and Political Participation: Exploring the

Causal Link. Political Behavior, 33(1), 357373. DOI 10.1007/s11109-010-9134-9

Campbell, D. (2009). Civic engagement and education: An empirical test of the sorting

model. American Journal of Political Science, 53(4), 771-786. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/20647950

Delli Carpini, M., & Keeter, S. (1996) What Americans know about politics and why

it matters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Eveland, W., Hayes, A., Shah, D., & Kwak, N. (2005). Understanding the relationship

between communication and political knowledge: A model comparison approach

using panel data. Political Communication 22(4), 423-46.

Finkel, S. (2002). Civic education and the mobilization of political participation in

developing democracies. Journal of Politics, 64(4), 994-1020.

Finkel, S. & Ernst, H. (2005) Civic education in post-apartheid South Africa:

Alternative paths to the development of political knowledge and democratic values.

Political Psychology, 26(3), 333-364. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/3792601

23

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

Finkel, S., & and Smith, A. (2011). Civic education, political discussion, and the social

transmission of democratic knowledge and values in a new democracy: Kenya

2002. American Journal of Political Science, 55(2), 417-435. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/23025060

Gibson, J. L. (2001). Social networks, civil society, and the prospects for consolidating

Russias democratic transition. American Journal of Political Science 45(1), 5168.

Hillygus, D. S. (2005). The missing link: Exploring the relationship between higher

education and political engagement. Political Behavior, 27(1), 25-47.

Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4500183

Klesner, J. L. (2007). Social capital and political participation in Latin America:

Evidence from Argentina, Chile, Mexico, and Peru. Latin American Research

Review, 42(2), 1-3. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4499368

Kuenzi, M.T. (2006). Nonformal education, political participation, and democracy:

findings from Senegal. Political Behavior, 28(1), 1-31. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/4500208

Lake, R., & Huckfeldt, R. (1998). Social capital, social networks, and political

participation. Political Psychology 19(3), 567-584.

Meyer, J., & Rubinson, R. (1975). Education and political development. Review of

Research in Education, 3(1), 134-162. Retrieved from

http://www.jstor.org/stable/1167257

Mutz, D. (2006). Hearing the other side: Deliberative versus participatory democracy.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

24

THE EFFECT OF EDUCATION ON POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

Nie, N., Junn, J., & Stehlik-Barry, K. (1996). Education and democratic citizenship in

America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Niemi, R., & Junn, J. (1998). Civic education: What makes students learn. New Haven,

CT: Yale University Press.

Syal, R. (2012). What are the effects of educational mobility on political interest and

participation in the Indian electorate? Asian Survey, 52(2), 423-439. Retrieved

from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/as.2012.52.2.423

25

También podría gustarte

- Reapportionment WebQuest Companion Worksheet FillableDocumento2 páginasReapportionment WebQuest Companion Worksheet FillableShauna VanceAún no hay calificaciones

- The Public School Advantage: Why Public Schools Outperform Private SchoolsDe EverandThe Public School Advantage: Why Public Schools Outperform Private SchoolsCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (3)

- The SAGE Handbook of Political CommunicationDocumento16 páginasThe SAGE Handbook of Political CommunicationMireia PéAún no hay calificaciones

- An Analysis of The Social Media Contents in Forming The Political Attitudes of Social Media UsersDocumento326 páginasAn Analysis of The Social Media Contents in Forming The Political Attitudes of Social Media UsersWimble Begonia Bosque100% (1)

- Finkel-2014-Public Administration and DevelopmentDocumento13 páginasFinkel-2014-Public Administration and DevelopmentCarmen NelAún no hay calificaciones

- Nelsen-Research Statement (7:15:19)Documento11 páginasNelsen-Research Statement (7:15:19)Matthew NelsenAún no hay calificaciones

- Nelsen-Research StatementDocumento11 páginasNelsen-Research StatementMatthew NelsenAún no hay calificaciones

- Political SocializationDocumento3 páginasPolitical Socializationglory vie100% (1)

- Jurnal PKN 1Documento11 páginasJurnal PKN 1Indahnovia DwiputriAún no hay calificaciones

- Results and Discussions PrefinalDocumento7 páginasResults and Discussions PrefinalEdward Kenneth DragasAún no hay calificaciones

- Civic EducationDocumento21 páginasCivic Educationjudith patnaanAún no hay calificaciones

- ResearchDocumento4 páginasResearchEryy CuiAún no hay calificaciones

- A Review On The Political Awareness of Senior High School Students of St. Paul University ManilaDocumento34 páginasA Review On The Political Awareness of Senior High School Students of St. Paul University ManilaAloisia Rem RoxasAún no hay calificaciones

- A Review On The Political Awareness of SDocumento34 páginasA Review On The Political Awareness of SAERELLA LOU NICORAún no hay calificaciones

- Latest Researches On Education and DemocracyDocumento5 páginasLatest Researches On Education and DemocracyFuchu AmatyaAún no hay calificaciones

- Policy Science - 06 - Chapter 1 - ShodhGangaDocumento34 páginasPolicy Science - 06 - Chapter 1 - ShodhGangaAnonymous j8laZF8Aún no hay calificaciones

- Influnce of Social Media On Political Polarization Among StudentsDocumento21 páginasInflunce of Social Media On Political Polarization Among StudentsClara Blake'sAún no hay calificaciones

- Political Activism of Social Work Educators Nancy L. Mary, DSWDocumento21 páginasPolitical Activism of Social Work Educators Nancy L. Mary, DSWAmory JimenezAún no hay calificaciones

- Why Civic Engagement Should Be Implemented in The Education System - EditedDocumento9 páginasWhy Civic Engagement Should Be Implemented in The Education System - EditedCandy OpiyoAún no hay calificaciones

- Student Unity: Students UnionDocumento18 páginasStudent Unity: Students UnionMuhammad FarhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Guidelines For Citizenship Education inDocumento53 páginasGuidelines For Citizenship Education inPaula Josefa Neira MagliocchettiAún no hay calificaciones

- Civic Learning Opportunities and Civic CommitmentsDocumento58 páginasCivic Learning Opportunities and Civic CommitmentsVladankaAún no hay calificaciones

- Improving Civic Education in SchoolsDocumento3 páginasImproving Civic Education in SchoolsAleksandar PečenkovićAún no hay calificaciones

- Is Political Ideology A Determinant of Youth Development Policy in The American States?Documento20 páginasIs Political Ideology A Determinant of Youth Development Policy in The American States?maria laboAún no hay calificaciones

- Democratic Attitudes Among High School PDocumento22 páginasDemocratic Attitudes Among High School PJihan nafisa20Aún no hay calificaciones

- Political SocializationDocumento9 páginasPolitical SocializationkushAún no hay calificaciones

- Democracy in Action-High School Single PageDocumento82 páginasDemocracy in Action-High School Single PageChristian LindkeAún no hay calificaciones

- Level of Political Awareness of Grade 11 StudentsDocumento16 páginasLevel of Political Awareness of Grade 11 StudentsSheila Mae Antido100% (1)

- Group 2 12 HUMSS AristotleDocumento17 páginasGroup 2 12 HUMSS AristotleZyra Mae Antido100% (1)

- This Goal Coupled With The REFLECT Approach That Government HasDocumento3 páginasThis Goal Coupled With The REFLECT Approach That Government Hasmuna moonoAún no hay calificaciones

- Public Engagement for Public Education: Joining Forces to Revitalize Democracy and Equalize SchoolsDe EverandPublic Engagement for Public Education: Joining Forces to Revitalize Democracy and Equalize SchoolsAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Constructivism On The Culture of Senior High School Humss Students Towards Strengthening Voter'S EducationDocumento63 páginasSocial Constructivism On The Culture of Senior High School Humss Students Towards Strengthening Voter'S EducationguerrerosheenamaeAún no hay calificaciones

- Hilly Gus PBDocumento23 páginasHilly Gus PBLjubica NovovićAún no hay calificaciones

- Enhancing Active Citizenship and Political Literacy Among Young Voters in High SchoolDocumento5 páginasEnhancing Active Citizenship and Political Literacy Among Young Voters in High Schoolchocolate cupcakeAún no hay calificaciones

- Mayne & HakhverdianDocumento41 páginasMayne & HakhverdianAlberto CastanedaAún no hay calificaciones

- Shayne Lada - ReportDocumento11 páginasShayne Lada - Reportapi-697508540Aún no hay calificaciones

- Socialization PDFDocumento53 páginasSocialization PDFIrisha AnandAún no hay calificaciones

- Political Preferences of 3rd-5Documento11 páginasPolitical Preferences of 3rd-5Janette SumagaysayAún no hay calificaciones

- High Quality Civic Education:: What Is It and Who Gets It?Documento6 páginasHigh Quality Civic Education:: What Is It and Who Gets It?gpnasdemsulselAún no hay calificaciones

- Background of The Study 1 ParagraphDocumento6 páginasBackground of The Study 1 Paragraphtito cagangAún no hay calificaciones

- Lit ReviewDocumento8 páginasLit Reviewapi-399395069Aún no hay calificaciones

- Political EngagementDocumento10 páginasPolitical EngagementTanuja Sai MaddiAún no hay calificaciones

- Thesis Megan FountainDocumento22 páginasThesis Megan FountainchanNelVlog :Aún no hay calificaciones

- New Kind of Patriotism 1Documento16 páginasNew Kind of Patriotism 1api-399395069Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ej 887904Documento30 páginasEj 887904Sehat IhsanAún no hay calificaciones

- Role of Media in Political SocializationDocumento13 páginasRole of Media in Political SocializationZEEB KHANAún no hay calificaciones

- Advertising Chinese Politics: The Effects of Public Service Announcements in Urban ChinaDocumento53 páginasAdvertising Chinese Politics: The Effects of Public Service Announcements in Urban ChinaNgo KunembaAún no hay calificaciones

- Maryland 4-H: Reaching Underserved and Underrepresented Youth and Adults As A National PerspectiveDocumento19 páginasMaryland 4-H: Reaching Underserved and Underrepresented Youth and Adults As A National PerspectiveMeg McGhinAún no hay calificaciones

- High School Civic Ed. Linked To Voting Participation, No Effect On Partisanship or Candidate SelectionDocumento3 páginasHigh School Civic Ed. Linked To Voting Participation, No Effect On Partisanship or Candidate SelectionLuna Media GroupAún no hay calificaciones

- Criticial Discourse Analysis On The Embedded Meanings of News ReportsDocumento81 páginasCriticial Discourse Analysis On The Embedded Meanings of News ReportsJayson PermangilAún no hay calificaciones

- Anilaa 1Documento9 páginasAnilaa 1RohailAún no hay calificaciones

- Greek Pre-Schoolers Crayon The Politicians: A Semiotic Analysis of Children's DrawingDocumento12 páginasGreek Pre-Schoolers Crayon The Politicians: A Semiotic Analysis of Children's DrawingSelenaAún no hay calificaciones

- Raise Your VoicesDocumento11 páginasRaise Your VoicesBeah SomozoAún no hay calificaciones

- 1115 SumeDocumento2 páginas1115 SumefadligmailAún no hay calificaciones

- Political LiteracyDocumento9 páginasPolitical LiteracySarah Mae Sumawang CeciliaAún no hay calificaciones

- Of Patriotism and Good Citizenship.: by Lakshana KathiresanDocumento4 páginasOf Patriotism and Good Citizenship.: by Lakshana KathiresanCindy Tan Xin YueAún no hay calificaciones

- QUALITATIVE JOURNAL FORMAT. SampleDocumento5 páginasQUALITATIVE JOURNAL FORMAT. SampleIVA LEI PARROCHAAún no hay calificaciones

- Research of Group 5 For EditingDocumento33 páginasResearch of Group 5 For EditingLloyd BarroAún no hay calificaciones

- Teachingportfolio 2015Documento24 páginasTeachingportfolio 2015api-246015714Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ahak Na ThesisDocumento28 páginasAhak Na ThesisJames Vincent JabagatAún no hay calificaciones

- Politics of Interest: Interest Groups and Advocacy Coalitions in American EducationDocumento24 páginasPolitics of Interest: Interest Groups and Advocacy Coalitions in American EducationintemperanteAún no hay calificaciones

- Mondragon, Northern SamarDocumento2 páginasMondragon, Northern SamarSunStar Philippine NewsAún no hay calificaciones

- ANNUAL ReportDocumento61 páginasANNUAL ReportTuta ChkheidzeAún no hay calificaciones

- Letter To Harris County From FADDocumento7 páginasLetter To Harris County From FADRebecca HAún no hay calificaciones

- ASIS Standards ProceduresDocumento10 páginasASIS Standards ProceduresToCaronteAún no hay calificaciones

- Villanueva - Reaction Paper (Swing Vote)Documento2 páginasVillanueva - Reaction Paper (Swing Vote)Katricia Elaine VillanuevaAún no hay calificaciones

- Look Ahead America Wisconsin and Geogia Reports On Election IntegrityDocumento47 páginasLook Ahead America Wisconsin and Geogia Reports On Election IntegrityUncoverDCAún no hay calificaciones

- A Roadmap Towards The Implementation of An Efficient Online Voting System in BangladeshDocumento5 páginasA Roadmap Towards The Implementation of An Efficient Online Voting System in BangladeshNirajan BasnetAún no hay calificaciones

- Ked675-2013 Senatorial Election ResultsDocumento17 páginasKed675-2013 Senatorial Election ResultsAnonymous 6TruhjYTjAún no hay calificaciones

- Form-46 Ballot Paper AccountDocumento1 páginaForm-46 Ballot Paper AccountBasir UsmanAún no hay calificaciones

- Angono, RizalDocumento2 páginasAngono, RizalSunStar Philippine NewsAún no hay calificaciones

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocumento2 páginasCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsAún no hay calificaciones

- Nov 17 CT Voter RegistrationDocumento8 páginasNov 17 CT Voter RegistrationHelen BennettAún no hay calificaciones

- Electoral Commission of Ghana: Detailed Regional StatisticsDocumento75 páginasElectoral Commission of Ghana: Detailed Regional StatisticsOfosu AnimAún no hay calificaciones

- By: April Joy G. Ursabia Melody Gale S. Lagra Hershey Lou Sheena L. LagsaDocumento12 páginasBy: April Joy G. Ursabia Melody Gale S. Lagra Hershey Lou Sheena L. LagsaAjurs UrsabiaAún no hay calificaciones

- Lesson Plan Subject: Social Science-Political Science Class: X Month: August-September Chapter 6: Political Parties No of Periods: 9Documento5 páginasLesson Plan Subject: Social Science-Political Science Class: X Month: August-September Chapter 6: Political Parties No of Periods: 9rushikesh patilAún no hay calificaciones

- Evm - Vvpat Final Converted Compressed - 1Documento114 páginasEvm - Vvpat Final Converted Compressed - 1Ashwin DAún no hay calificaciones

- Ross Swartzendruber, Senate District 12 QuestionnaireDocumento6 páginasRoss Swartzendruber, Senate District 12 QuestionnaireStatesman JournalAún no hay calificaciones

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Provincial Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocumento2 páginasCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Provincial Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsAún no hay calificaciones

- Voting: The Mathematics of ElectionsDocumento34 páginasVoting: The Mathematics of ElectionsDaniel Luis AguadoAún no hay calificaciones

- Accents Magazine - Issue 01Documento28 páginasAccents Magazine - Issue 01accentsonlineAún no hay calificaciones

- 6 (A) Vice-President of IndiaDocumento10 páginas6 (A) Vice-President of IndiaIAS EXAM PORTALAún no hay calificaciones

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocumento2 páginasCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsAún no hay calificaciones

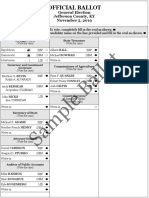

- Sample BallotsDocumento1 páginaSample BallotsCourier Journal50% (2)

- Electoral Board ManualDocumento55 páginasElectoral Board ManualCABARO NHORE100% (1)

- Election Law NotesDocumento20 páginasElection Law NotesChristian AbenirAún no hay calificaciones

- The Social Smart ContractDocumento27 páginasThe Social Smart ContractCésar G. Rincón GonzálezAún no hay calificaciones

- FACTS: Benito and Private Respondent Pagayawan Were 2 of 8 Candidates Vying For TheDocumento2 páginasFACTS: Benito and Private Respondent Pagayawan Were 2 of 8 Candidates Vying For TheCharles Roger RayaAún no hay calificaciones

- Voting Law Changes 2012: Brennan Center ReportDocumento124 páginasVoting Law Changes 2012: Brennan Center ReportCREWAún no hay calificaciones

- Lawsuit Filed Against Michigan's Independent Redistricting CommissionDocumento24 páginasLawsuit Filed Against Michigan's Independent Redistricting CommissionMLive.comAún no hay calificaciones