Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Van Paasschen 2014 - Consistent Emotions Evoked by Abstract Art PDF

Cargado por

Olumuyiwa OjoTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Van Paasschen 2014 - Consistent Emotions Evoked by Abstract Art PDF

Cargado por

Olumuyiwa OjoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

See

discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261436948

Consistent Emotions Elicited by

Low-Level Visual Features in

Abstract Art

Article January 2014

DOI: 10.1163/22134913-00002012

CITATION

READS

195

4 authors, including:

Jorien van Paasschen

Universit degli Studi di Tre

8 PUBLICATIONS 280 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

David Melcher

Universit degli Studi di Tre

114 PUBLICATIONS 1,552

CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Available from: Jorien van Paasschen

Retrieved on: 05 September 2016

Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

brill.com/artp

Consistent Emotions Elicited by Low-Level Visual

Features in Abstract Art

Jorien van Paasschen 1 , Elisa Zamboni 1 , Francesca Bacci 2 and David Melcher 1,

1

Center for Mind/Brain Sciences (CIMeC), University of Trento, Palazzo Fedrigotti,

Corso Bettini 31, 38068 Rovereto, Italy

2

Museo dArte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, Italy

Received 12 April 2013; accepted 2 September 2013

Abstract

It is often assumed that works of art have the ability to elicit emotion in their observers. An emotional response to a visual stimulus can occur as early as 120 ms after stimulus onset, before object

categorisation can take place. This implies that emotions elicited by an artwork may depend in part

on bottom-up processing of its visual features (e.g., shape, colour, composition) and not just on object recognition or understanding of artistic style. We predicted that participants are able to judge

the emotion conveyed by an artwork in a manner that is consistent across observers. We tested this

hypothesis using abstract paintings; these do not provide any reference to objects or narrative contexts, so that any perceived emotion must stem from basic visual characteristics. Nineteen participants

with no background in art rated 340 abstract artworks from different artistic movements on valence

and arousal on a Likert scale. An intra-class correlation model showed a high consistency in ratings

across observers. Importantly, observers used the whole range of the rating scale. Artworks with a

high number of edges (complex) and dark colours were rated as more arousing and more negative

compared to paintings containing clear lines, bright colours and geometric shapes. These findings

provide evidence that emotions can be captured in a meaningful way by the artist in a set of low-level

visual characteristics, and that observers interpret this emotional message in a consistent, uniform

manner.

Keywords

Aesthetic experience, perception, emotion, aesthetic viewing

To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: david.melcher@unitn.it

Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2014

DOI:10.1163/22134913-00002012

100

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

1. Introduction

It is often assumed that works of art have the ability to elicit emotion in

their observers, and indeed, people often ascribe emotional valence to artworks (Cskszentmihlyi and Robinson, 1990). However, little is known as

to whether artworks are able to induce similar, shared emotions in spectators

(comparable to, for example, the response to an emotional face), or whether

observers experience a divergent range of emotions when viewing the same

artwork (rendering the experience of the artwork purely subjective). A comprehensive theory of emotion perception would need to take into account this

affective response to visual art, music and other stimuli. Here, we start by

investigating whether there are commonalities in emotional responses to abstract artworks or whether instead, there is truth in the old adage that theres

no accounting for taste when it comes to art.

We begin by discussing the neuropsychological basis underlying emotional

and aesthetic experiences. We then consider why it is plausible that at least

some aspects of the experience of emotions conveyed by artworks may be

homogenous across observers. Next we will present theories from artists and

art historians regarding the ways in which art, in particular abstract paintings,

might evoke emotion. Finally, we present our hypotheses regarding emotional

cues in abstract artworks and explain how we mean to test these empirically.

1.1. The Role of Emotion in Aesthetic Perception

Art has the power to disturb us, agitate us, or make us weep (Ellis, 1999,

p. 163). But how is an artwork able to trigger such a response, and when in

the viewing process do these emotions occur? Inherent to it being a visual

stimulus, it follows that visual art must initially be processed based on early

visual properties (e.g., shape, colour) in the primary visual areas within the

occipital cortex. An emotional response to a visual stimulus (e.g., a face) can

occur as early as 120 ms after stimulus onset (Pizzagalli et al., 1999, 2002),

before object categorisation can take place. Barrett and Bar (2009) have suggested that before object recognition takes place, gist-level visual information

(in the case of a visual artwork this could include low spatial frequency information, colour and some aspects of composition) engages fronto-parietal

attention circuits, which in turn relay affective information about the stimulus

back to the dorsal stream as an initial estimate of its affective and motivational

value. Heightened attention to a given stimulus then modulates object recognition within the ventral stream (e.g., Pessoa et al., 2003; Shulman et al., 1997)

and allows for the stimulus to be experienced more vividly. Thus, this affective

information guides our vision.

The notion that emotional responses already occur during the very first

stages of vision implies that emotions elicited by an artwork may depend at

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

101

least in part on bottom-up processing of its visual features such as shape and

colour, in addition to higher cognitive processes such as object recognition or

understanding of artistic style (for review, see Melcher and Cavanagh, 2011).

Abstract artworks provide an interesting case study for attempts to understand

perception of emotion in artworks. Contrary to most artistic movements, abstract art is a category that defines paintings which do not intend to give a

faithful imitation of visual reality. There are no recognizable objects or contexts that could evoke emotion, in contrast to most of the existing studies

of emotion expression. In this sense, the emotional response to abstract artworks might be compared to that of music, where explicit reference to real

objects or scenes is rare (Blood and Zatorre, 2001; for review, see Koelsch,

2010; Melcher and Zampini, 2011). Since most of what we know about visual

emotion perception is based on studies of responses to stimuli like faces and

photographs, abstract artworks provide a unique and valuable stimulus set for

studying perception of emotion in visual stimuli.

Indeed, many artists have claimed that their abstract artworks are, in the

words of Jackson Pollock, expressing . . . feelings rather than illustrating

(OConnor, 1967, p. 79). Mark Rothko argued that his works expressed basic human emotions . . . tragedy, ecstasy, doom (Baal-Teshuva, 2003, p. 56).

As described below in more detail, artists have in many cases provided specific, testable claims about how and why their works evoke these emotions.

Implicit in most of these claims is the idea that there are commonalities in the

emotional response of different viewers of abstract artworks. Thus, in addition

to more narrative or top-down influences on emotion perception for artworks,

visual properties such as colour and form, which are dominant in abstract art

but also important in representational art, may play a role in the emotional

response to some artworks.

Some evidence for agreement when it comes to the emotion expressed by

abstract art comes from a study showing that children were able to correctly

match one of two abstract paintings to a representational target painting in

terms of conveyed emotion (Blank et al., 1984). This indicates that even young

children have the ability to detect emotion in an artwork, despite probably not

having a very developed concept of artistic style. A different study, also including (preschool) children, has shown that children as young as three are able to

distinguish different artistic styles (Hasenfus et al., 1983), which suggests that

nave observers tend to decode or understand works of art at a deeper level

than might be assumed (p. 861). A behavioural study comparing representational and indeterminate art (paintings which contain strong suggestions of

natural shapes, but no actual formal objects) found no difference in scores reflecting how much the artworks affected participants emotionally (Ishai et al.,

2007). The authors concluded that emotional and aesthetic judgments (which

were comparable for representational and indeterminate artworks) appeared

102

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

to be based on low and intermediate visual features, independent of semantic

meaning. A similar finding was observed by Takahashi (1995) in an intriguing

study in which participants who had no specific background in art were asked

to produce abstract line drawings reflecting a particular topic (e.g., anger, joy,

femininity, illness). Next, the drawings were grouped according to topic and a

larger group of different participants was asked to pick the five drawings that

best expressed the topic. Takahashi found considerable agreement in the top

five drawings chosen for each category, with 3555% of participants agreeing on the most appropriate drawing for each topic. Takahashi concluded that

there may be a . . . shared intuition that contributes visually to ones understanding of the concept that a drawing means to express (p. 675). Although

both the study design and results are intriguing, it remains unclear to what extent participants truly agreed on the representative value of the drawings. For

example, the drawings were already grouped according to theme when participants selected the most representative drawing for that theme. This is quite

different to asking people to pick the most representative drawing for a particular theme out of all available drawings there may have been considerable

crossing over of drawings and categories.

From a cognitive neuroscience perspective, neuroimaging studies suggest

that there are central, supramodal neural mechanisms that underlie emotional

evaluation and experience. The dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, for example,

has been implicated in the representation of emotions independent of modality

(Adolphs, 2009; Peelen et al., 2010) and in peoples appraisal and experience

of emotions as well as the evaluation of emotional content of a stimulus, irrespective of the nature of the emotion (Kober et al., 2008; Lee and Siegle,

2012; Reiman et al., 1997). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that

there are neural mechanisms in the brain that are involved in the cross-modal

representation of different emotion categories.

1.2. Artists and Art Theorists on Emotion Perception in Abstract Art

One important question, before starting any study of the perception of abstract

artwork, is which works to choose for study. For the present study, we adopted

a stylistic criterion in order to create two stimulus sets. As proposed by Alfred

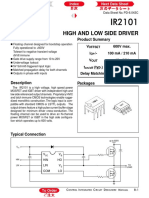

H. Barr on the occasion of the exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art (1936),

we can think of abstract paintings as falling in one of two broad categories:

geometrical abstract art and non-geometrical abstract art (see Fig. 1).

Barrs stylistic analysis outlines the presence of a scientific attitude that is

found in Geometrical Abstract Art: the analytical use of colour by the Pointillists, and the methodical breakdown of space into basic geometrical units by

Cubists and Constructivists. Geometrical Abstract Art is characterized by a

well-planned design that is based on the use of uniform colours and geometrical elements such as lines and shapes. Non-Geometrical Abstract Art, instead,

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

103

Figure 1. Depiction of the historical developments in art leading to two main tendencies in

abstract art. From Albert H. Barr Jrs exhibition catalogue for the MoMA show Cubism and

Abstract Art (1936). This figure is published in color in the online version.

uses elements chosen for their symbolic and subjective value. Gauguin and the

Fauve artists chose to represent reality through non-imitative colours, in order

to augment the symbolic content of their paintings. The Expressionists and

Futurists exploited colours expressive potential, and the Dada and Surrealist

artists incorporated chance effects of doodling marks, which were believed

to stem from a persons unconscious. Non-Geometrical abstract art can thus

be characterised by the presence of fluid curved lines and sweeping strokes,

104

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

gestural spreading of colours in hasty marks or splashes and drippings and,

generally speaking, an intense, almost sloppy execution, as if they were made

because of an inner necessity of the artist rather than being the result of careful

planning or theoretical reasoning.

In the current study we explored whether the emotional response to paintings from these two art movements shows a meaningful difference in arousal

or valence traceable to the artworks intrinsic characteristics. We included

paintings from Abstract Expressionism (AbEx) and Geometric Abstraction

(Geom). Abstract Expressionism paintings are arguably non-geometric and

are characterised by apparently random strokes and splashes of paint; there

is a complete absence of recognisable forms (examples are works by Hans

Hartung and Antonio Corpora, see Fig. 2A). Geometric Abstraction paintings,

instead, are characterised by distinct geometric shapes and clear lines (for example, works by Aldo Schmid and Luigi Senesi, see Fig. 2B).

1.3. Rationale for the Current Study

As discussed above, there might be general principles that help explain why art

evokes an emotional response in viewers, and these principles have a neurological basis, hence are common to all observers. We predict that nave observers

with no formal background in arts would be able to pick up the emotion conveyed by an artwork, and that they would do so in a manner that is consistent

across observers. We tested this hypothesis using images of abstract paintings.

One distinct advantage of this class of stimuli is that they do not provide any

reference to objects or narrative contexts as a site of emotional expression,

so that any perceived emotion must stem from basic visual features such as

colour, shape, and composition. To ensure participants could not place the artworks in any semantic context, it was especially important to include only

nave subjects in the study. We compared ratings from nave participants on

valence (happy/sad) and arousal (exciting/calm) dimensions for 170 Abstract

Expressionism and 170 Geometric Abstraction paintings.

Unlike previous studies on this topic, we have included a much larger set

of artworks (n = 340) to be rated. As a comparison, Takahashi (1995) used

46 line drawings per emotional category, while Blank et al. (1984) used 16

abstract artworks. In addition, participants in the current study had the option

to rate the artwork as neutral if they felt the artwork was not particularly

emotional, as opposed to the forced choice method employed by Takahashi

and Blank and colleagues, where artworks had to be matched to emotional

labels or categories. Furthermore, our participants rated to what extent they

felt an artwork corresponded to a particular emotional category. Using this

approach, we were able to calculate reliability in scoring patterns between

the different raters for all artworks, instead of assessing whether a particular

painting was chosen to represent an emotional label above chance level.

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

105

(A)

(B)

Figure 2. (A) Examples of Abstract Expressionism works (Hans Hartung T 1963-H13, 1963;

and Antonio Corpora Notturno, 1952). (B) Examples of Geometric Abstraction works (Aldo

Schmid No title (from the Sequenze cycle), 19651966; and Luigi Senesi Percorsocromatico (verde-rosso), 1974).

106

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

We predicted that ratings would be consistent across observers for paintings

from both art movements. We were also interested in whether artworks from

one movement may be experienced as more positive and/or more exciting than

the other. Given that these artworks cannot differ on semantic content, subjects

must base their evaluation on low-level perceptual features such as colour,

composition, shape, and style. Our participants knew equally little about the

backgrounds of either art movement. Therefore, any differences in affective

ratings between the two art streams are unlikely to be the result of successfully

mastering one style but not the other. Instead, such a result would support the

idea that particular visual features that characterise one art movement but not

the other evoke emotions in their observers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Nineteen participants (6 men, 13 women, mean age 23.5 4.8 years, range

1938) took part in the study. Participants were students from the University

of Trento or residents from the local community (Rovereto, Italy), recruited

through advertisements on the internet. All participants had normal or corrected to normal vision. Participants had no specific background or training

in art or art history. Most participants visited a modern arts museum at least

once a year (mean 1.9 1.3). All were paid for their participation. All participants gave written informed consent prior to participation. The experimental

procedures were in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the University of

Trento and Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Materials

Participants were asked to rate digital images of abstract artworks from two

major abstract art movements (Abstract Expressionism and Geometric Abstraction). We used digitalised images of paintings from the MART collection (Museo dArte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto), and

freely available images through the websites of the Guggenheim museum, the

MoMA, the Whitney museum, and Tate Modern. Furthermore, artwork reproductions in books were scanned in by the researchers.

Out of this larger collection of digital images, FB, EZ and JVP selected 170

paintings from each art movement for the rating experiment. The suitability

of each artwork was discussed and artworks were selected only if all three

authors reached consensus on the suitability of the painting for a particular

category (AbEx or Geom). A further 12 paintings were selected for a practice

run. For Abstract Expressionism we included paintings that had no clear lines

or forms. For Geometric Abstraction, we chose paintings that had clearly defined lines and recognisable shapes. Paintings were excluded if they were part

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

107

of a composition of different paintings, if they depicted an actual figure or object, if there were any letters or numbers (or signs that appeared as such) on the

painting, if they displayed formal characteristics belonging to both categories,

or if there was a three-dimensional object attached to the painting.

To obtain some uniformity in size of the stimuli without distorting the original proportions of the paintings, the largest dimension on each painting was

resized to 600 pixels; the smaller dimension was then resized in relation to

that. Paintings were shown on a Toshiba Satellite Pro L500-1VZ laptop using

NBS Presentation software (version 16.0, www.neurobs.com).

2.3. Measures

For the rating task, participants were required to rate each artwork on one of

two dimensions: Arousal (ranging from calm to excited) and Valence (ranging

from sad to happy), in a fashion similar to the instructions given to participants

who rated pictures for the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang

et al., 2008). There was one question per trial, so that each painting was viewed

twice in total (one viewing per question). The order of the questions (Arousal

or Valence) and paintings was randomised.

Following the example of the IAPS, in the instructions provided at the

start of the experiment, the Arousal dimension was explained as the extent

to which the painting made participants feel stimulated, excited, frenzied, jittery, wide-awake, aroused, or rather completely relaxed, calm, sluggish, dull,

sleepy, unaroused. During the actual experiment, we only presented the labels

calm and excited. The Arousal scale consisted of five figures taken from

the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM; Hodes et al., 1985) that depicted a little man ranging from eyes closed (calm) to exploding with eyes wide open

(excited). The Valence dimension was explained as the extent to which each

painting made subjects feel happy, pleased, satisfied, contented, hopeful, or on

the other end of the scale, completely unhappy, annoyed, unsatisfied, melancholic, despaired. Again, during the actual experiment we only presented the

simplified labels sad and happy. The Valence scale consisted of five faces

from the WongBaker faces pain scale (Wong and Baker, 1988). The faces

were similar to cartoon style smiley faces and ranged from an inverted Ushape mouth and hanging eyebrows (sad) to a big smile with raised eyebrows

(happy).

The rating scale was depicted on the screen, and pictures of each rating

option were attached to buttons on the keyboard using five buttons to the right

of the U key and five buttons to the right of the J key. The position of

the two rating scales (top row or bottom row of keys) was counterbalanced

between participants.

108

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

2.4. Procedure

All participants performed a practice run with a different subset of paintings

before engaging in the actual experiment. Each trial started with a fixation

cross (500 ms) along with printed information on the dimension that the participant would be rating the painting on. For Arousal, it said calm/excited

and for Valence it said sad/happy. A painting was then shown for 2000 ms.

During this presentation no rating could be made. Immediately following presentation, a screen appeared with the word rating and the appropriate scale.

Participants were instructed to make their response as fast as possible and not

to think too long about their response. There was a 1000 ms blank screen before the start of the next trial. The experiment was self-paced and lasted about

50 min, depending on the speed with which participants gave their rating.

3. Results

3.1. Rating Consistency

Rating scores were first converted to standardised z-scores to correct for any

bias in rating across subjects. In order to assess whether participants rated the

paintings in a consistent way, we analysed the standardised rating scores from

each participant for each painting using a two-way random effects intra-class

correlation (ICC) model to test consistency for each dimension separately.

The ICC coefficient for Valence was very high (ICC = 0.845; 95% CI =

0.820.87), suggesting a consistent pattern of valence ratings for different

paintings across participants. Consistency in valence rating was slightly higher

for AbEx paintings (ICC = 0.844; 95% CI = 0.800.88) than for Geom paintings (ICC = 0.786; 95% CI = 0.730.83). The ICC coefficient for Arousal

was also high (ICC = 0.854; 95% CI = 0.830.88). In contrast to the valence

ratings, ratings for arousal were more consistent for Geom paintings (ICC =

0.866; 95% CI = 0.830.90) than for AbEx paintings (ICC = 0.757; 95%

CI = 0.700.81).

To test whether the consistency in scores does not simply reflect a vast

amount of neutral ratings, we calculated the frequency of the mean rating

awarded to each artwork. These results are summarised in Table 1. Frequency

tables showed that about 50% of the AbEx and 30% of Geom artworks received a mean Valence rating that was either lower than 2.5 (sad) or higher

than 3.5 (happy). On the Arousal dimension, 38% of AbEx paintings and

60% of Geom paintings received scores that clearly reflected calm or excited. This means that especially with regards to the Valence ratings for the

Geom artworks, the majority of artworks was rated as neutral. To check that

the consistency was not merely driven by these neutral ratings, we repeated the

intraclass correlation but excluded the neutrally rated artworks from the anal-

109

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

Table 1.

Number of paintings with mean high, neutral, and low Arousal and Valence ratings. AbEx:

Abstract Expressionism; Geom: Geometric Abstraction

Mean rating

Low (<2.5)

Neutral (2.53.5)

High (>3.5)

Valence

Arousal

AbEx

Geom

AbEx

Geom

75

85

10

18

120

32

22

105

43

86

69

15

yses. Consistency in ratings remained high for both Valence (AbEx: ICC =

0.749; 95% CI = 0.660.83; Geom: ICC = 0.895; 95% CI = 0.840.94) and

Arousal (AbEx: ICC = 0.871; 95% CI = 0.820.92; Geom: ICC = 0.910;

95% CI = 0.880.94).

3.2. Differences Between the Two Art Types

To explore whether there were differences in ratings between AbEx and Geom

paintings, standardised ratings were entered into a repeated measures analysis of variance using Art Type (AbEx, Geom) as a between-group factor

and Dimension (Arousal, Valence) as a within-group factor. There was a significant interaction between Art Type and Dimension (F (1, 338) = 238.149,

p < 0.001). No other effects were found. A follow-up independent samples

t-test showed that AbEx paintings were rated as significantly more negative

(mean raw score 2.69 0.54; note that raw scores are used in the text for

meaningfulness; for the analyses standardised z-scores were used) than Geom

paintings (mean raw score 3.17 0.44) (t (338) = 8.978, p < 0.001). Geom

paintings were rated as significantly more calm (mean raw score 2.53 0.64)

(t (338) = 8.519, p < 0.001) than AbEx paintings (mean raw score 3.09

0.49). Figure 3 illustrates these results.

There was a highly significant positive relationship between standardised

ratings for valence and arousal for Geom paintings (r = 0.547, p < 0.001), as

well as for AbEx paintings (r = 0.177, p = 0.021).

To see whether AbEx and Geom paintings differed significantly in terms

of basic visual features, we compared saturation (vividness of colour, where

lower saturation colours contain more grey), brightness (luminance; or the

black/white quality), and complexity (as assessed by an index of the number of

edges detected in each artwork) in an independent samples t-test. Assumptions

for equality of the variances were not met for all three features; hence the degrees of freedom were adjusted. AbEx and Geom paintings did not differ significantly on saturation (t (316.565) = 1.914, p = 0.168 (Bonferroni corrected

for multiple comparisons); mean saturation AbEx: 31.18% 17.06; mean sat-

110

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

Figure 3. Mean standardised ratings for Arousal and Valence for 340 paintings. AbEx: Abstract

Expressionism; Geom: Geometric Abstraction. This figure is published in color in the online

version.

uration Geom: 35.31% 22.21). However, Geom paintings were significantly

brighter than AbEx artworks (t (323.348) = 5.217, p < 0.001 (Bonf.corr.);

mean brightness AbEx: 53.49% 17.41; mean brightness Geom: 64.59%

21.43), while works in the AbEx category were significantly more complex

than in the Geom group (t (317.550) = 4.618, p < 0.001 (Bonf.corr)).

We also sampled the mean hue (i.e., wavelength) in degrees for each artwork and calculated a mean hue for each art stream by converting the degrees

to radians (mean hue AbEx: 30.71; mean hue Geom: 11.32). The coordinates

for the vectors making up each radian were entered into a bootstrap procedure

with 10 000 iterations and a threshold of = 0.05. The bootstrap procedure

showed that the set of AbEx and Geom artworks significantly differed in mean

hue (p = 0.006). Overall the AbEx works tended to golden orange, while the

Geom set leaned to more red.

Subsequently, we correlated ratings for valence and arousal with saturation, brightness and complexity indices (a meaningful correlation with hue

was not possible since the values were either vectors or degrees). Valence

ratings were positively correlated with arousal ratings for both art streams

(AbEx: r = 0.177, p = 0.021; Geom: r = 0.547, p < 0.001). For AbEx artworks, valence ratings increased as paintings became more colourful, bright,

and complex (saturation: r = 0.231, p = 0.003; brightness: r = 0.610, p <

0.001; complexity: r = 0.233, p = 0.002). AbEx artworks were rated as

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

111

more arousing the more complex (r = 0.330, p < 0.001) and dark they were

(r = 0.183, p = 0.019), but we found no significant correlation between

arousal ratings and saturation (r = 0.083, p = 0.288). Interestingly, a different pattern was found for Geom artworks: these were rated more positively

the brighter they were (r = 0.503, p < 0.001), while there was no relation

between valence ratings and saturation (r = 0.064, p = 0.406) or complexity (r = 0.145, p = 0.058). On the other hand, arousal ratings were higher

for more colourful and complex paintings (saturation: r = 0.204, p = 0.008;

complexity: r = 0.230, p = 0.002) whereas no significant correlation existed

between arousal ratings and brightness (r = 0.085, p = 0.268).

4. Discussion

The current study obtained valence and arousal ratings for a large set of abstract artworks. We hypothesised that observers who are nave to art are able to

pick up emotion conveyed by abstract artworks in a consistent manner. Indeed

we found highly consistent ratings on both valence and arousal for artworks

from Abstract Expressionism and Geometric Abstraction, suggesting that the

artworks evoked common emotional processes across observers. Importantly,

observers placed artworks consistently along either dimension, showing that

the agreement in scoring is not simply due to all works being rated as neutral.

We also explored whether there were differences in ratings between the two

art movements. Overall, ratings were more positive and calm for paintings belonging to Geometric Abstraction compared to Abstract Expressionism, which

were judged as sadder and more exciting.

Because our participants were nave to art, they were not able to base their

valence and arousal judgments on anything other than the basic visual features

presented to them by an artwork. Given that the artworks bear no reference to

real-life objects, we pose that an emotional response to such stimuli is based to

a large part on bottom-up visual features. Similar ideas have been proposed by

some of the artists producing art these artworks, and indeed affective reactions

have been reported previously for single visual stimuli such as simple geometric shapes (e.g., Larson et al., 2007, 2011) and colours (e.g., Kaya and Epps,

2004; Moller et al., 2009; Ou et al., 2004). However, to date there is little empirical evidence for consistent affective reactions across different observers in

response to visual art. Many models of aesthetic viewing emphasise the individuality of aesthetic experiences and affective reactions to art these are

regarded as the interplay between an observer and the situation (e.g., Jacobsen

et al., 2006; Leder et al., 2004). Our findings complement studies of the role

of context and top-down factors by showing also the existence of a consistent

interpretation of emotion for abstract artworks by nave participants.

112

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

4.1. Bottom-up Emotion Cues

The idea that colour can trigger an emotional response is generally accepted,

but the precise relationship between colour and affective reaction is complex and context-dependent (for review, see Elliot and Maier, 2007; Gage,

1999). Colour includes hue, saturation, and brightness. The relationship between colours may be as important as the colours themselves, and the finding

that many of the most positive images contained a combination of bright yellow and blue is consistent with the long-standing idea that complementary

colours hold a special place in visual art (Gage, 1999).

When looking at the presence of specific colours, and ignoring the role of

the interactions between colours, it is possible to compare the current findings

to previous studies using single colour patches. The AbEx and Geom artworks

in the present study did not differ significantly on saturation, an indication of

the intensity of colours used. Moreover, valence ratings for Geom artworks

did not correlate with saturation, suggesting that colour intensity does not explain the higher proportion of happy ratings for Geom artworks. The two

sets of artworks in the current study differed on mean hue, with AbEx artworks overall containing more golden-orange and Geom works overall more

red. As mentioned above, the previous literature on colour and emotion (or

preference) contains contradictory findings regarding specific hues. In one

study investigating peoples emotional reaction to colours, a red-purple hue

was among the most pleasant hues whereas a yellow hue was rated as least

pleasant (Valdez and Mehrabian, 1994). A red-purple hue was also rated as

less dominant than a green-yellow hue. Similarly, a different study comparing 20 colours on a likedislike scale found that purplish blue was the most

liked whereas muddy yellow was the most disliked (Ou et al., 2004), a finding

corroborated by a different study comparing male and female participants

although the men seemed to prefer blue-green to purplish blue (Hurlbert and

Ling, 2007). However, colours that are liked or disliked when seen on their

own may be combined in a particular artwork. Ou and colleagues (2004)

pointed out that although there is a strong correlation between preference for

individual colours and perceived harmony of a colour pair, there are colours

for which this does not hold. The relationship between colour preference and

combinations of more than one colour has not been properly investigated, but

is presumably more complex.

One possibility is that the presence of certain colours in abstract artworks

would directly influence emotion ratings. Using computer vision techniques,

Yanulevskaya and colleagues (2012) trained a classifier to recognise which

statistical patterns in abstract paintings predict whether that painting was rated

as positive or negative by human observers. The algorithm was able to predict

human emotion ratings based on colour (CIELAB) and form (SIFT: Lowe,

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

113

2004) information. They also found that brighter yellow, blue and red were

associated with positive emotions, while dark colours were related to negative

emotions. In the current study, the Geom artworks as a set were brighter than

the AbEx artworks, which received more sad ratings. This is in line with the

study by Yanulevskaya and colleagues, who found that darker colours were

predictive of a negative rating.

Another possibility for the difference in ratings between the two art streams

is that the presence of clearly discernible shapes in the Geom artworks may

have resulted in more well-defined uniform planes. As described above, a classifier trained on form and texture features (SIFT) was able to predict whether

human judgments of the emotion of an abstract artwork were positive or negative (Yanulevskaya et al., 2012). It has been previously demonstrated that

when using simple geometric shapes, people prefer stimuli with a high figureground contrast, presumably because this facilitates processing fluency (Reber

et al., 2004). Reber and colleagues further argue that stimuli with less information are more pleasing to the observer, again because this is easier to

process. The finding that Geom artworks were on average brighter and less

complex than AbEx artworks may indicate that Geom paintings contain more

large contrasting sections. Complexity was assessed using an index of edge

detection; AbEx paintings were found to contain more edges and were thus

more fragmented, containing more angles than Geom paintings. An earlier

study demonstrated that people preferred large abstract geometrical shapes and

characters over smaller versions of the same stimulus, supposedly because biologically speaking larger specimens convey a sense of power, attractiveness,

and physical strength (Silvera et al., 2002).

Bar and Neta (2006) showed that if given a choice, people prefer the rounder

version of neutral everyday objects (a sofa, a watch, and so on). They attributed this to a potential sense of threat that is conveyed by sharp angles.

This sense of threat is even conveyed by simple geometric shapes such as

triangles, a finding that was traced back to threatening facial features such

as downward pointing eyebrows in an angry face (Aronoff, 2006; Larson et

al., 2007). A downward pointing triangle was perceived as particularly threatening, as expressed by heightened brain activity in the amygdala (Larson et

al., 2009), a subcortical structure involved in basic emotional processing and

threat detection (e.g., LeDoux, 2000; Vuilleumier et al., 2003). Larson and colleagues (2009) pointed out that circles, one of the control stimuli in their study,

were not threatening but elicited greater activation in visual processing areas

compared to other geometric shapes and thus can be regarded as more potent

and salient visual stimuli. Similarly, statistical patterns in abstract paintings

corresponding to straight lines and smooth curves were associated with positive emotions while chaotic patterns were associated with negative emotions,

even if these arrays appeared in positive colours (Yanulevskaya et al., 2012).

114

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

However, there is a limit to the role of bottom-up features like shape, since topdown factors must play an important role in judging the emotional content of

an object or scene. For example, objects that were round but carried a negative

valence (e.g., a bomb, or a snake) were not preferred over negative sharp objects (Leder et al., 2011). Round objects were only preferred over sharp angles

if their valence was neutral or positive, showing that object associations also

play an important role in emotion perception. Similarly, it is unlikely that the

ratings of the IAPS pictures is determined largely by bottom-up visual cues,

but instead depends on recognition of specific objects and situations.

Overall, the idea that visual characteristics such as brightness, low visual

complexity, and round shape tend to be regarded as more positive may help to

explain why participants in our study were so consistent in their higher happy and calm ratings for the Geom artworks compared to AbEx artworks.

As shown in the study by Yanulevskaya and colleagues (2012), at least some

of the visual features in abstract artworks are basic enough that they can be

used by computational vision algorithms to predict human emotion ratings.

Thus, although the identity of objects and other forms of top-down knowledge

undoubtedly influence emotional responses, artists are also able to manipulate

basic visual features such as colour, shape and brightness in order to modulate

the respone of viewers.

4.2. Limitations of the Current Study and Directions for Future Research

Although consistency in ratings in the current study was high even when the

neutrally rated paintings were excluded from the analysis, it should be noted

that a large proportion of the Geometric Abstraction artworks (70%) was rated

as neutral. This could be the result of the particular artworks that we selected,

but it may also suggests that for this set of artworks perhaps the happysad

scale was not the best possible dimension to assess affective responses (as a

comparison, on the calmexcited scale, less than half (40%) of the Geom

artworks received a neutral rating). One aim of the current study was to test

the feasibility of developing a dataset of abstract artworks, similar to the International Affection Picture Scale (Lang et al., 2008), for use in studying the

neural correlates of emotional responses to a range of visual stimuli such as

faces, pictures and abstract paintings. The valence and arousal measures allow for making such direct comparisons, but future research could consider a

wider spectrum of emotions and obtain ratings for different facets of emotion.

For example, a study investigating emotions evoked by music, Zentner et al.

(2008) identified nine factors, each including two or more items. For example,

agitated and nervous relate to the factor tension, while energetic and

fiery relate to the factor power. Moreover, this study took into account ratings for perceived and felt emotion, i.e., what emotion was expressed by the

music, and what emotion was felt by the subject. An open question for future

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

115

research is the extent to which the complex mechanisms involved in creating

emotional responses to music, which changes dynamically over time (for review, see Juslin and Vstfjll, 2008), are similar to methods used for static

images.

In addition to including more specific emotional labels to characterise what

emotions abstract art evokes, future research could focus on supramodal emotional processes that viewing abstract art shares with viewing emotional scenes

or faces. If evoked emotions through abstract art are indeed highly consistent,

it should be possible, for example, to classify brain activity related to viewing a

happy artwork in a similar way to viewing a happy scene. If there are brain

areas that respond to happy stimuli, irrespective of presentation type, then

we would expect to find supramodal areas of activation regardless of whether

the participants are shown abstract artworks, faces, or scenes.

4.3. Conclusions

We report here consistent emotional evaluations of abstract artworks. Our results support the idea that artists can use low-level visual characteristics to

influence the emotional perception of observers. Participants rated the Geometric Abstraction artworks as more calm and more positive compared to

those belonging to Abstract Expressionism. The Geometric Abstraction artworks were overall brighter, contained discernible, more rounded shapes, and

more figure-ground contrast compared to the Abstract Expressionism artworks. Previous research has demonstrated that such visual features are

individually regarded as positive, which may explain why ratings in our

participants were so consistent. The observers in our study had no formal

training in art, yet awarded comparable emotional ratings to particular artworks. Hence, we conclude that affective reactions to viewing art may depend

at least in part on bottom-up visual features, and that these aspects of emotion

perception in art may be more universal than previously assumed.

Acknowledgement

This research was funded by a grant from the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio

di Trento e Rovereto awarded to FB and DM.

References

Adolphs, R. (2009). The social brain: Neural basis of social knowledge, Annu. Rev. Psychol. 60,

693716.

Aronoff, J. (2006). How we recognize angry and happy emotion in people, places, and things,

Cross-Cultural Res. 40, 83105.

Baal-Teshuva, J. (2003). Mark Rothko, 19031970: Pictures as Drama. Taschen, Cologne, Germany.

116

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

Bar, M. and Neta, M. (2006). Humans prefer curved visual objects, Psychol. Sci. 17, 645648.

Barr, A. H. Jr (1936). Papers [3146:1043]. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York,

NY, USA.

Barrett, L. F. and Bar, M. (2009). See it with feeling: Affective predictions during object perception, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 364(1521), 13251334.

Blank, P., Massey, C., Gardner, H. and Winner, E. (1984). Perceiving what paintings express,

in: Cognitive Processes in the Perception of Art, 19th edn. W. R. Crozier and A. J. Chapman

(Eds), pp. 127143. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Blood, A. J. and Zatorre, R. J. (2001). Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with

activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion, Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98,

1181811823.

Cskszentmihlyi, M. and Robinson, R. E. (1990). The Art of Seeing: An Interpretation of the

Aesthetic Encounter. Getty Publications, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Elliot, A. J. and Maier, M. A. (2007). Color and psychological functioning, Curr. Dir. Psychol.

Sci. 16, 250254.

Ellis, R. D. (1999). The dance form of the eyes: What cognitive science can learn from art,

J. Conscious. Stud. 6, 161175.

Gage, J. (1999). What Meaning had colour in early societies? Cambridge Archaeol. J. 9, 109

126.

Hasenfus, N., Martindale, C. and Birnbaum, D. (1983). Psychological reality of cross-media

artistic styles, J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 9, 841863.

Hodes, R. L., Cook, E. W. and Lang, P. J. (1985). Individual differences in autonomic response:

conditioned association or conditioned fear? Psychophysiology 22, 545560.

Hurlbert, A. C. and Ling, Y. (2007). Biological components of sex differences in color preference, Curr. Biol. 17, R623R625.

Ishai, A., Fairhall, S. L. and Pepperell, R. (2007). Perception, memory and aesthetics of indeterminate art, Brain Res. Bull. 73, 319324.

Jacobsen, T., Schubotz, R. I., Hfel, L. and Cramon, D. Y. V. (2006). Brain correlates of aesthetic judgment of beauty, Neuroimage 29, 276285.

Juslin, P. N. and Vstfjll, D. (2008). Emotional responses to music: The need to consider

underlying mechanisms, Behav. Brain Sci. 31, 559575; discussion 575621.

Kaya, N. and Epps, H. H. (2004). Relationship between color and emotion: A study of college

students, Coll. Stud. J. 38, 396405.

Kober, H., Barrett, L. F., Joseph, J., Bliss-Moreau, E., Lindquist, K. and Wager, T. D. (2008).

Functional grouping and cortical-subcortical interactions in emotion: A meta-analysis of

neuroimaging studies, Neuroimage 42, 9981031.

Koelsch, S. (2010). Towards a neural basis of music-evoked emotions, Trends Cogn. Sci. 14,

131137.

Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M. and Cuthbert, B. N. (2008). International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Affective Ratings of Pictures and Instruction Manual. Technical Report A-8.

University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA.

Larson, C. L., Aronoff, J., Sarinopoulos, I. C. and Zhu, D. C. (2009). Recognizing threat: A simple geometric shape activates neural circuitry for threat detection, J. Cogn. Neurosci. 21,

15231535.

Larson, C. L., Aronoff, J. and Stearns, J. J. (2007). The shape of threat: Simple geometric forms

evoke rapid and sustained capture of attention, Emotion 7, 526534.

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

117

Larson, C. L., Aronoff, J., Steuer, E. L. and Threat, I. A. T. . (2011). Simple geometric shapes

are implicitly associated with affective value, Motiv. Emot. 36, 404413.

Leder, H., Belke, B., Oeberst, A. and Augustin, D. (2004). A model of aesthetic appreciation

and aesthetic judgments, Br. J. Psychol. 95, 489508.

Leder, H., Tinio, P. P. L. and Bar, M. (2011). Emotional valence modulates the preference for

curved objects, Perception 40, 649655.

LeDoux, J. E. (2000). Emotion circuits in the brain, Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 23, 155184.

Lee, K. H. and Siegle, G. J. (2012). Common and distinct brain networks underlying explicit

emotional evaluation: A meta-analytic study, Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 7, 521534.

Lowe, D. G. (2004). Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints, Int. J. Comput.

Vis. 60, 91110.

Melcher, D. P. and Cavanagh, P. (2011). Pictorial cues in art and in visual perception, in: Art

and the Senses, F. Bacci and D. P. Melcher (Eds), pp. 359394. Oxford University Press,

Oxford, UK.

Melcher, D. P. and Zampini, M. (2011). The sight and sound of music: Audio-visual interactions

in science and the arts, in: Art and the Senses, F. Bacci and D. Melcher (Eds), pp. 265292.

Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Moller, A. C., Elliot, A. J. and Maier, M. A. (2009). Basic hue-meaning associations, Emotion

9, 898902.

OConnor, F. V. (1967). Jackson Pollock. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

Ou, L.-C., Luo, M. R., Woodcock, A. and Wright, A. (2004). A study of colour emotion and

colour preference. Part I: Colour emotions for single colours, Color Res. Appl. 29, 381389.

Peelen, M. V., Atkinson, A. P. and Vuilleumier, P. (2010). Supramodal representations of perceived emotions in the human brain, J. Neurosci. 30, 1012710134.

Pessoa, L., Kastner, S. and Ungerleider, L. G. (2003). Neuroimaging studies of attention: From

modulation of sensory processing to top-down control, J. Neurosci. 23, 39903998.

Pizzagalli, D., Lehmann, D., Hendrick, A. M., Regard, M., Pascual-Marqui, R. D. and Davidson,

R. J. (2002). Affective judgments of faces modulate early activity (160 ms) within the

fusiform gyri, Neuroimage 16, 663677.

Pizzagalli, D., Regard, M. and Lehmann, D. (1999). Rapid emotional face processing in the

human right and left brain hemispheres: An ERP study, Neuroreport 10, 26912698.

Reber, R., Schwarz, N. and Winkielman, P. (2004). Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure:

is beauty in the perceivers processing experience? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 8, 364382.

Reiman, E. M., Lane, R. D., Ahern, G. L., Schwartz, G. E., Davidson, R. J., Friston, K. J., Yun,

L. S. and Chen, K. (1997). Neuroanatomical correlates of externally and internally generated

human emotion, Am. J. Psychiatry 154, 918925.

Shulman, G. L., Corbetta, M., Buckner, R. L., Raichle, M. E., Fiez, J. A., Miezin, F. M. and

Petersen, S. E. (1997). Top-down modulation of early sensory cortex, Cereb. Cortex 7, 193

206.

Silvera, D. H., Josephs, R. A. and Giesler, R. B. (2002). Bigger is better: The influence of

physical size on aesthetic preference judgments, J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 15, 189202.

Takahashi, S. (1995). Aesthetic properties of pictorial perception, Psychol. Rev. 102, 671683.

Valdez, P. and Mehrabian, A. (1994). Effects of color on emotions, J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 123,

394409.

Vuilleumier, P., Armony, J. L., Driver, J. and Dolan, R. J. (2003). Distinct spatial frequency

sensitivities for processing faces and emotional expressions, Nat. Neurosci. 6, 624631.

118

J. van Paasschen et al. / Art & Perception 2 (2014) 99118

Wong, D. and Baker, C. (1988). Pain in children: Comparison of assessment scales, Pediatr.

Nurs. 14, 917.

Yanulevskaya, V., Uijlings, J., Bruni, E., Sartori, A., Zamboni, E., Bacci, F., Melcher, D. and

Sebe, N. (2012). In the Eye of the Beholder: Employing statistical analysis and eye tracking

for analyzing abstract paintings categories and subject descriptors, in: Proceedings of the

20th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM12. ACM, New York, USA.

Zentner, M., Grandjean, D. and Scherer, K. R. (2008). Emotions evoked by the sound of music:

characterization, classification, and measurement, Emotion 8, 494521.

También podría gustarte

- Kinesthetic Empathy in Creative and Cultural PracticesDe EverandKinesthetic Empathy in Creative and Cultural PracticesDee ReynoldsAún no hay calificaciones

- The Emotionally Evocative Effects of PaintingsDocumento12 páginasThe Emotionally Evocative Effects of PaintingschnnnnaAún no hay calificaciones

- Cognitive Processes in the Perception of ArtDe EverandCognitive Processes in the Perception of ArtCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1)

- 2016 - Aesthetic Emotions Across Arts A Comparison Between Painting and Music - Miu, Piţur, Szentágotai-TatarDocumento9 páginas2016 - Aesthetic Emotions Across Arts A Comparison Between Painting and Music - Miu, Piţur, Szentágotai-TatarFabian MaeroAún no hay calificaciones

- The Perception and Evaluation of Visual ArtDocumento22 páginasThe Perception and Evaluation of Visual ArtFranchesca Dyne RomarateAún no hay calificaciones

- Neuroesthetics - A Step Toward The Comprehension of Human CreativityDocumento4 páginasNeuroesthetics - A Step Toward The Comprehension of Human CreativityrosarioareAún no hay calificaciones

- Attachment Theory - Affect Regulation Mirror Neurons and The Third HandDocumento9 páginasAttachment Theory - Affect Regulation Mirror Neurons and The Third Handapi-320676174Aún no hay calificaciones

- Art KnowledgeDocumento3 páginasArt KnowledgeChirag HablaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Porter Institute For Poetics and SemioticsDocumento17 páginasPorter Institute For Poetics and SemioticsRozika NervozikaAún no hay calificaciones

- Aesthetics of Visual Expressionism PDFDocumento28 páginasAesthetics of Visual Expressionism PDFleninlingaraja100% (1)

- (Consciousness, Literature and The Arts) Tone Roald, Johannes Lang-Art and Identity - Essays On The Aesthetic Creation of Mind-Rodopi (2013)Documento219 páginas(Consciousness, Literature and The Arts) Tone Roald, Johannes Lang-Art and Identity - Essays On The Aesthetic Creation of Mind-Rodopi (2013)PifpafpufAún no hay calificaciones

- Affect Regulation Mirror Neurons and The Third Hand Formulating Mindful Empathic Art InterventionsDocumento9 páginasAffect Regulation Mirror Neurons and The Third Hand Formulating Mindful Empathic Art Interventionsjagui1Aún no hay calificaciones

- Logos, Ethos, PathosDocumento9 páginasLogos, Ethos, Pathosjean constantAún no hay calificaciones

- Understanding Humor in Instrumental Music. Beethoven's RondoDocumento14 páginasUnderstanding Humor in Instrumental Music. Beethoven's RondoIvana VuksanovićAún no hay calificaciones

- University of Illinois PressDocumento15 páginasUniversity of Illinois PressMonica PnzAún no hay calificaciones

- Tuningintoart BBS InPressDocumento4 páginasTuningintoart BBS InPressfraneksiejekAún no hay calificaciones

- Motion, emotion and empathy in aesthetic experienceDocumento8 páginasMotion, emotion and empathy in aesthetic experienceMelchiorAún no hay calificaciones

- Art and EmotionDocumento65 páginasArt and Emotionazman bin hilmiAún no hay calificaciones

- BAYLEN, CLEO, C.-Unit II - LESSON 3 - Art Appreciation and The Human FacultiesDocumento13 páginasBAYLEN, CLEO, C.-Unit II - LESSON 3 - Art Appreciation and The Human FacultiesCLEO BAYLENAún no hay calificaciones

- The Effect of Picture-Formations On Emotional Moods: Ruth HampeDocumento10 páginasThe Effect of Picture-Formations On Emotional Moods: Ruth Hampedaria antoniaAún no hay calificaciones

- Art and The Ineffable - W. E. Kennick (1961)Documento13 páginasArt and The Ineffable - W. E. Kennick (1961)vladvaideanAún no hay calificaciones

- Thought Is A Material - Talking With Mel Bochner About Space, Art and Language - Alexander KranjecDocumento10 páginasThought Is A Material - Talking With Mel Bochner About Space, Art and Language - Alexander KranjecHalisson SilvaAún no hay calificaciones

- What Does The Brain Tell Us About Abstract Art?: Human NeuroscienceDocumento4 páginasWhat Does The Brain Tell Us About Abstract Art?: Human NeuroscienceENRIQUEAún no hay calificaciones

- Guy Rohrbaugh - Ontology of ArtDocumento13 páginasGuy Rohrbaugh - Ontology of ArtkwsxAún no hay calificaciones

- Art ExperienceDocumento10 páginasArt ExperienceJ LarsenAún no hay calificaciones

- The Aesthetic Experience With Visual Art "At First Glance": Paul J. LocherDocumento14 páginasThe Aesthetic Experience With Visual Art "At First Glance": Paul J. LocherFaizan Akram -169-sec-DAún no hay calificaciones

- Read To A Conference "Filmbuilding," Held at Ryerson in 1999. Published As A CD-Rom, Titled FilmbuildingDocumento24 páginasRead To A Conference "Filmbuilding," Held at Ryerson in 1999. Published As A CD-Rom, Titled FilmbuildingBailey FensomAún no hay calificaciones

- Seth BEHOLDERSSHARE 070817Documento36 páginasSeth BEHOLDERSSHARE 070817Fatou100% (1)

- Art Appreciation: Mt. Carmel College of San Francisco, IncDocumento12 páginasArt Appreciation: Mt. Carmel College of San Francisco, IncKriza mae alvarezAún no hay calificaciones

- Ramos - Toward A Phenomenological Psychology of Art AppreciationDocumento20 páginasRamos - Toward A Phenomenological Psychology of Art AppreciationLeila CzarinaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Correspondences Between Sound and Light and Colour-Music: SKB "Prometei"Documento22 páginasThe Correspondences Between Sound and Light and Colour-Music: SKB "Prometei"olazzzzzAún no hay calificaciones

- Art Neuro ZekiDocumento9 páginasArt Neuro ZekichainofbeingAún no hay calificaciones

- 2b Enacting-Musical-EmotionsDocumento25 páginas2b Enacting-Musical-EmotionsYuri Alexndra Alfonso CastiblancoAún no hay calificaciones

- Juslin - Emotional Responses To MusicDocumento49 páginasJuslin - Emotional Responses To MusicVeruschka MainhardAún no hay calificaciones

- Daltrozzo Et Al 2011Documento14 páginasDaltrozzo Et Al 2011RaminIsmailoffAún no hay calificaciones

- Art, Meaning, and Perception: A Question of Methods For A Cognitive Neuroscience of ArtDocumento18 páginasArt, Meaning, and Perception: A Question of Methods For A Cognitive Neuroscience of ArtLuciano LeonAún no hay calificaciones

- Cognitive Neuroscience and ActingDocumento14 páginasCognitive Neuroscience and ActingMontse BernadAún no hay calificaciones

- Picasso AssignmentDocumento8 páginasPicasso AssignmentneyplayerAún no hay calificaciones

- Colour MusicDocumento42 páginasColour MusicVeronika ShiliakAún no hay calificaciones

- Art, Psychology, and Neuroaesthetics: Appreciate Art For Health and Well-BeingDocumento8 páginasArt, Psychology, and Neuroaesthetics: Appreciate Art For Health and Well-BeingDanys ArtAún no hay calificaciones

- s Davachi Looking InwardDocumento16 páginass Davachi Looking InwardŁukasz MorozAún no hay calificaciones

- Mapping Aesthetic Emotion Terms 2017Documento54 páginasMapping Aesthetic Emotion Terms 2017Chara VlachakiAún no hay calificaciones

- Cahier1 - When Is Research Artistic Research - PDFDocumento35 páginasCahier1 - When Is Research Artistic Research - PDFAlfonso Aguirre DergalAún no hay calificaciones

- Music and The Abstract MindDocumento9 páginasMusic and The Abstract MinddschdschAún no hay calificaciones

- A Sense of Connection - Synesthetic Metaphor, Inter Media, and The Possibility of Acquired SynesthesiaDocumento28 páginasA Sense of Connection - Synesthetic Metaphor, Inter Media, and The Possibility of Acquired SynesthesiaDave WallAún no hay calificaciones

- Sound Painting - Audio Description in Another Light - Josélia Nenes COM OCRDocumento4 páginasSound Painting - Audio Description in Another Light - Josélia Nenes COM OCRVeronicaMattosoAún no hay calificaciones

- NeuroaestheticsDocumento6 páginasNeuroaestheticsIvereck IvereckAún no hay calificaciones

- Enacting Musical ExperienceDocumento26 páginasEnacting Musical ExperienceДмитрий ШийкаAún no hay calificaciones

- How Art WorksDocumento15 páginasHow Art WorksAllan Jay NatividadAún no hay calificaciones

- Roles and Rabbits: Conceptual Blending of Theatrical Roles in White Rabbit Red RabbitDocumento24 páginasRoles and Rabbits: Conceptual Blending of Theatrical Roles in White Rabbit Red Rabbitlaine71Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Psychology of Entertainment Media Blurring The Lines Between Entertainment and PersuasionDocumento32 páginasThe Psychology of Entertainment Media Blurring The Lines Between Entertainment and PersuasionJoeAún no hay calificaciones

- arts notes finalsDocumento6 páginasarts notes finalsJam TabucalAún no hay calificaciones

- Zbikowski Des Herzraums AbschiedDocumento16 páginasZbikowski Des Herzraums AbschiedJuciara NascimentoAún no hay calificaciones

- Neuropsychology of Art Reviews Brain Damage in ArtistsDocumento3 páginasNeuropsychology of Art Reviews Brain Damage in ArtistsLoreto Alonso AtienzaAún no hay calificaciones

- MetaphorsInArt PetrenkoDocumento37 páginasMetaphorsInArt Petrenkovanag99152Aún no hay calificaciones

- What Is The Cognitive Neuroscience of ArDocumento20 páginasWhat Is The Cognitive Neuroscience of ArMario VillenaAún no hay calificaciones

- What Are Aesthetic Emotions Co-Author FiDocumento86 páginasWhat Are Aesthetic Emotions Co-Author FiHeoel GreopAún no hay calificaciones

- The Neuroscience of ArtDocumento3 páginasThe Neuroscience of ArtVivek Mahadevan100% (1)

- A Phenomenological Route To A Composer's Subjectivity'Documento13 páginasA Phenomenological Route To A Composer's Subjectivity'IggAún no hay calificaciones

- Mersch Dieter Epistemologies of AestheticsDocumento176 páginasMersch Dieter Epistemologies of AestheticsfistfullofmetalAún no hay calificaciones

- Elevator Traction Machine CatalogDocumento24 páginasElevator Traction Machine CatalogRafif100% (1)

- Product ListDocumento4 páginasProduct ListyuvashreeAún no hay calificaciones

- CG Module 1 NotesDocumento64 páginasCG Module 1 Notesmanjot singhAún no hay calificaciones

- 中美两国药典药品分析方法和方法验证Documento72 páginas中美两国药典药品分析方法和方法验证JasonAún no hay calificaciones

- Stability Calculation of Embedded Bolts For Drop Arm Arrangement For ACC Location Inside TunnelDocumento7 páginasStability Calculation of Embedded Bolts For Drop Arm Arrangement For ACC Location Inside TunnelSamwailAún no hay calificaciones

- Qualitative Research EssayDocumento9 páginasQualitative Research EssayMichael FoleyAún no hay calificaciones

- Patent for Fired Heater with Radiant and Convection SectionsDocumento11 páginasPatent for Fired Heater with Radiant and Convection Sectionsxyz7890Aún no hay calificaciones

- B. Pharmacy 2nd Year Subjects Syllabus PDF B Pharm Second Year 3 4 Semester PDF DOWNLOADDocumento25 páginasB. Pharmacy 2nd Year Subjects Syllabus PDF B Pharm Second Year 3 4 Semester PDF DOWNLOADarshad alamAún no hay calificaciones

- Tetracyclines: Dr. Md. Rageeb Md. Usman Associate Professor Department of PharmacognosyDocumento21 páginasTetracyclines: Dr. Md. Rageeb Md. Usman Associate Professor Department of PharmacognosyAnonymous TCbZigVqAún no hay calificaciones

- PC3 The Sea PeopleDocumento100 páginasPC3 The Sea PeoplePJ100% (4)

- Datasheet PDFDocumento6 páginasDatasheet PDFAhmed ElShoraAún no hay calificaciones

- Update On The Management of Acute Pancreatitis.52Documento7 páginasUpdate On The Management of Acute Pancreatitis.52Sebastian DeMarinoAún no hay calificaciones

- ASA 2018 Catalog WebDocumento48 páginasASA 2018 Catalog WebglmedinaAún no hay calificaciones

- MS For Brick WorkDocumento7 páginasMS For Brick WorkSumit OmarAún no hay calificaciones

- 3GPP TS 36.306Documento131 páginas3GPP TS 36.306Tuan DaoAún no hay calificaciones

- Lesson Plan: Lesson: Projectiles Without Air ResistanceDocumento4 páginasLesson Plan: Lesson: Projectiles Without Air ResistanceeltytanAún no hay calificaciones

- CAT Ground Engaging ToolsDocumento35 páginasCAT Ground Engaging ToolsJimmy Nuñez VarasAún no hay calificaciones

- Material and Energy Balance: PN Husna Binti ZulkiflyDocumento108 páginasMaterial and Energy Balance: PN Husna Binti ZulkiflyFiras 01Aún no hay calificaciones

- Embankment PDFDocumento5 páginasEmbankment PDFTin Win HtutAún no hay calificaciones

- RPG-7 Rocket LauncherDocumento3 páginasRPG-7 Rocket Launchersaledin1100% (3)

- Ro-Buh-Qpl: Express WorldwideDocumento3 páginasRo-Buh-Qpl: Express WorldwideverschelderAún no hay calificaciones

- OpenROV Digital I/O and Analog Channels GuideDocumento8 páginasOpenROV Digital I/O and Analog Channels GuidehbaocrAún no hay calificaciones

- Seed SavingDocumento21 páginasSeed SavingElectroPig Von FökkenGrüüven100% (2)

- ADIET Digital Image Processing Question BankDocumento7 páginasADIET Digital Image Processing Question BankAdarshAún no hay calificaciones

- Gotham City: A Study into the Darkness Reveals Dangers WithinDocumento13 páginasGotham City: A Study into the Darkness Reveals Dangers WithinajAún no hay calificaciones

- مقدمةDocumento5 páginasمقدمةMahmoud MadanyAún no hay calificaciones

- Proceedings of The 16 TH WLCDocumento640 páginasProceedings of The 16 TH WLCSabrinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Religion in Space Science FictionDocumento23 páginasReligion in Space Science FictionjasonbattAún no hay calificaciones

- The Templist Scroll by :dr. Lawiy-Zodok (C) (R) TMDocumento144 páginasThe Templist Scroll by :dr. Lawiy-Zodok (C) (R) TM:Lawiy-Zodok:Shamu:-El100% (5)

- LSUBL6432ADocumento4 páginasLSUBL6432ATotoxaHCAún no hay calificaciones

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionDe EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (402)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionDe EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (2475)

- The Art of Personal Empowerment: Transforming Your LifeDe EverandThe Art of Personal Empowerment: Transforming Your LifeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (51)

- The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentDe EverandThe Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (4121)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismDe EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismAún no hay calificaciones

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesDe EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1632)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeDe EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeAún no hay calificaciones

- Becoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonDe EverandBecoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (1477)

- Take Charge of Your Life: The Winner's SeminarDe EverandTake Charge of Your Life: The Winner's SeminarCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (174)

- The 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageDe EverandThe 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (7)

- The One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsDe EverandThe One Thing: The Surprisingly Simple Truth Behind Extraordinary ResultsCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (708)

- The 16 Undeniable Laws of Communication: Apply Them and Make the Most of Your MessageDe EverandThe 16 Undeniable Laws of Communication: Apply Them and Make the Most of Your MessageCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (72)

- The Motive: Why So Many Leaders Abdicate Their Most Important ResponsibilitiesDe EverandThe Motive: Why So Many Leaders Abdicate Their Most Important ResponsibilitiesCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (220)

- The Silva Mind Method: for Getting Help from the Other SideDe EverandThe Silva Mind Method: for Getting Help from the Other SideCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (51)

- Liberated Love: Release Codependent Patterns and Create the Love You DesireDe EverandLiberated Love: Release Codependent Patterns and Create the Love You DesireAún no hay calificaciones

- Uptime: A Practical Guide to Personal Productivity and WellbeingDe EverandUptime: A Practical Guide to Personal Productivity and WellbeingAún no hay calificaciones

- The Science of Self Discipline: How Daily Self-Discipline, Everyday Habits and an Optimised Belief System will Help You Beat Procrastination + Why Discipline Equals True FreedomDe EverandThe Science of Self Discipline: How Daily Self-Discipline, Everyday Habits and an Optimised Belief System will Help You Beat Procrastination + Why Discipline Equals True FreedomCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (865)

- Recovering from Emotionally Immature Parents: Practical Tools to Establish Boundaries and Reclaim Your Emotional AutonomyDe EverandRecovering from Emotionally Immature Parents: Practical Tools to Establish Boundaries and Reclaim Your Emotional AutonomyCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (201)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeDe EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (253)

- Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeDe EverandIndistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (4)

- Summary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisDe EverandSummary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (4)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDe EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (30)

- Quantum Success: 7 Essential Laws for a Thriving, Joyful, and Prosperous Relationship with Work and MoneyDe EverandQuantum Success: 7 Essential Laws for a Thriving, Joyful, and Prosperous Relationship with Work and MoneyCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (38)

- The Day That Turns Your Life Around: Remarkable Success Ideas That Can Change Your Life in an InstantDe EverandThe Day That Turns Your Life Around: Remarkable Success Ideas That Can Change Your Life in an InstantCalificación: 5 de 5 estrellas5/5 (93)