Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Archie, Marlene M - An Afrocentric Critique of Mudimbes

Cargado por

Diego MarquesDescripción original:

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Archie, Marlene M - An Afrocentric Critique of Mudimbes

Cargado por

Diego MarquesCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

1

AN AFROCENTRIC CRITIQUE OF MUDIMBES BOOK,

THE INVENTION OF AFRICA: GNOSIS, PHILOSOPHY, AND THE

ORDER OF KNOWLEDGE

MARLENE M. ARCHIE

Temple University

INTRODUCTION

The focus of this analysis is chapter I: DISCOURSE OF POWER AND

KNOWLEDGE OF OTHERNESS, in Mudimbe's The Invention of Africa(TIOA). The

aim is to provide an understanding of the elements Mudimbe borrows from his

culture and tradition and how he is situated in that culture and tradition. Through

this analysis I seek to locate the author making an Afrocentric assessment of this

work based on the three paradigmatic approaches in the discipline of Africology:

functional, categorical and etymological. Location theory will also be used as a basis

of this assessment. Asante, as cited in Welsh-Asante (l993p.57), expounds on

Considerations of Location Theory when he asserts: "Location theory is a branch of

centric theory and reflects the same interest as centric theory on the question of

place. It is essentially a process of explaining how human beings come to make

decisions about the external world which takes into consideration all of the attitudes

and behaviors which constitute psychological and cultural place."

PURPOSE

The book attempts a kind of archaeology of African gnosis as a system of

knowledge in which important or major philosophical questions have arisen

concerning first the form, the content, and the style of "Africanizing" knowledge; and

second, the status of traditional systems of thought and their possible relation to the

normative genre of knowledge (TIOA, 1988,p.x). Mudimbe's intent is to investigate

and discuss the themes of the foundations of discourse about Africa. Therefore, what

he attempts is a critical synthesis of the complex questions about knowledge and

power in and of Africa. What is being asked is "What is the basis for discussions

about Africa, and from where and whom did it come?" According to Dr. Mudimbe,

"discourses have not only sociohistorical origins but also epistemological contexts."

Since epistemology is a branch of philosophy that investigates the origin, nature,

methods and limits of human knowledge, one should consider, as Dr. Mudimbe

contends, "the origins of the philosophies which support or negate these discourses to

be the catalyst which makes these discourses possible and which can also account for

them in an essential way."

Mudimbe argues that the various discourses themselves

establish the worlds of thought in which people conceive

their identity. Western anthropologist and missionaries

have introduced distortions not only for outsiders but also

for Africans trying to understand themselves (TIOA,

backcover).

What Mudimbe does is try to combine diverse conceptions into

a coherent whole; he goes on an intellectual voyage of discovering who he is from a

position outside his culture. He views his culture as Other.

CHAPTER I: DISCOURSE OF POWER AND KNOWLEDGE OF

OTHERNESS

An epistemological analysis of Africanism is offered---an examination of the limits

and validity of African tradition and cultural knowledge. The focus is on the

European and Africanist interpretations of African history and African philosophy;

Mudimbe contends, the colonial experience manifest a new historical form and the

possibility of radically new types of discourses on African traditions and cultures

(VJM,1988,p.1). What he does, however, is address the issue from an other than

Afrocentric perspective.

Structure of Argument

Mundimbe constructs his argument around themes. In this chapter, the

purpose is to discuss the theme: The restructuring of Africa. Mudimbe attempts an

illustration of how the basis for discussion of Africa comes from the genesis of

philosophies that deny or affirm discourse on Africa. The subtopics of the chapter

are: Colonizing structure and marginality; Discursive formations and otherness; and

African genesis.

Discussion

The colonizing structure is significant to Mudimbe's analysis of discourse; I

believe his view of the structure is addressed from a Eurocentric perspective:

The two words derive from the Latin word colere, meaning

to cultivate or to design. Indeed the historical colonial

experience does not and obviously cannot reflect the

peaceful connotations of these words (colonization and

colonialism). But it can be admitted that the colonists, as

well as the colonialist have all tended to organize and

transform non-European areas into fundamentally

European constructs (p.1).

His discussion places the African and the interest of the African as object of the

inquiry. Africa is referred to from an imperialistic perspective. In order to address

an issue from a Afrocentric perspective the African should be subject.

Colonization changed the constructs of Africa from Afrocentric to

Eurocentric. The restructuring of Africa according to Mudimbe encompasses three

general areas: exploitation of the physical land and space; the domination of the

mind and body; and the infusion of western ideas into a civilization that was already

established.

Mudimbe's reference to discussions on colonialism and its inconsistency with

economic development, emphasizes his point of Africa not having an economic

system. His choice of various discourses about the colonial experience of Africa

seemed to be a bit confusing. While his notion of colonialism where economic growth

is concerned is accurate, his comment on colonialism as an historical accident, is not

approached Afrocentrically. Mundimbe has this to say in response to Fieldhouse's

view that colonialism was a "largely unplanned and ...transient phase in the evolving

relationship between more and less developed parts of the world":

Thus colonialism has been some kind of historical accident which on the

whole, according to this view, was not the worst thing that could have

happened to the black continent.(p.3)

This remark indicates dislocation. Although I did not find Mudimbe to declare

to be an Afrocentrist, I'm aware Mudimbe is an African writing about African

phenomena. This is an instance where he discusses data about Africans from the

perspective of the European, not the African.

Although Dr. Midumbe depicts the negative ramifications of European

intervention in Africa and points out that the colonizing structure is responsible for

marginality, I do not believe he is addressing the issue from an Afrocentric

perspective. His discussion places the African and the interests of the African as

object of the inquiry. The context of views presented----the environment which is

history seems to place Mudimbe outside his own historical experiences. According to

Asante (l990), "the decapitated text is the contribution of the author who writes with

no discernible African element; the aim appears to be to distance herself or himself

from the African cultural self."

Although the author's philosophical support leans toward the European, he

has obvious creative abilities as demonstrated in the multidisciplinary scope of his

work. However, he shows less concern with disciplinary issues than with the

arrangement of forces that account for the establishment and transfiguration of

discourses. Additionally, the complexity of Mudimbe's subjects does not yield a clear

direction. His concern is not with determining if the discourses of history and

anthropology reflect an objective African reality but with looking at the conditions

that allow for their possibility. And in so doing he indicates a direction away from the

African experience. In order to address an issue from an Afrocentric perspective the

African should be subject.

In an attempt to show how marginality----underdevelopment is derived from

colonial structure, Mudimbe describes what he refers to as the intermediate space.

His reference to discourse is offered in support of his contention that this "space could

be viewed as the major signifier of underdevelopment. It reveals the strong tension

between a modernity that often is an illusion of development, and a tradition that

sometimes reflects a poor image of a mythical past" (TIOA, pg.5). He asserts, that

this space and the apparent contradictions to modernization forces one to look at the

models and meanings of renewing Africa. Although what Mudimbe offers is a view of

how this "marginal space" functions as evidence of the pressure which encourages

social scientist to reevaluate modernization programs, he brings his view and the

views of others from the point of the anthropologist, not the African. He chooses

terms not created by the African; his language denotes the author is not placed in

his own center. Mundimbe contends: "Marginality designates the intermediate

space between the so-called African tradition and the project modernity of

colonialism. It is apparently an urbanized space in which, as noted by S. Amin,

"vestiges of the past..that are still living realities (tribal ties, for example), often

continue to hide the new structures." His reference to African tradition as "so-called"

is perceived in a deprecatory sense. Several choices of reference, including Amin and

his use of pejorative terms (tribal ties), urges one to consider also the direction of

Mudimbe's interest. There seems to be a tendency along the lines of Eurocentric

space.

Mudimbe seems to choose language and a style which corresponds with a

Europe centered approach; he portrays the situation of the colonizing structure from

the perspective of the colonist----the European.

Several factors influence my determination of Mudimbe's dislocation. The

author borrows elements from outside his culture and tradition. Those borrowed

elements as depicted herein, seem to have a common influence on the way Mudimbe

expresses himself in this work. Asante (l990), informs us of the elements of locating a

text; a text must be seen in the light of language, attitude, and direction when the

serious reader wants to locate it. From the writers' own textual expression the

Afrocentric critic is able to ascertain the cultural address of the author (Asante,l990).

In Mudimbe's discussion of Discursive formations and Otherness, he cites, P.

Boulle, Seidman, and Turgot in his treatment of the African aesthetic. His view on

the issues that come from paintings from the 15 century on, and the allocation of an

"African object" to 19th century anthropology, is offered from the perspective of the

anthropologist. In his discussion of African art, and his references, Mudimbe relies

heavily on Foucault as well as Levi-Strauss. If Mudimbe buys into the

anthropological constructs of Levi-Strauss, one must consider the direction of his

interest to be toward Euro-centric constructs.

Mudimbe's reference to African objects, and his choice of quotes reflect a

western view of art forms. The discourse presented in this section, which is

demeaning to the African, is purely in the interest of what African art symbolizes to

the European. Mudimbe's reference to African art forms is consistent with those in

his European citations. For example, "These objects, which perhaps are not art at all

in their "native context," become art by being given simultaneously an aesthetic

character and a potentiality for producing and reproducing other artistic forms"

(TIOA,p.10). When he discusses standards for art that come from "inside the powerknowledge field of cultures" in his reference to African art, he seems to distance

himself from African culture. His identification with the African aesthetic seems to

be minimized while he seems to embrace the notion of a European aesthetic view.

There is no affirmation of the African aesthetic. His attitude leans toward a

Eurocentric range of influence.

According to Welsh-Asante (1993), even though Mudimbe's work....will

undoubtedly continue to have influence among those who study the aesthetic of

Africa, it does not make a major contribution to our understanding of aesthetics. She

further adds, "it is truly disconcerting for an African scholar to be so pre-occupied

with seeking approval from the European community" (Welsh-Asante,1993p.252).

Mudimbe's contention that anthropological discourses on human varieties

forms a power-knowledge political system which opposes the "other" or the African

may be accurate but is done so from other than an Afrocentric perspective. The

subtle quality of the author's expression of ideas about Africa, and the various

choices of reference, places doubt on his view of the world, and his place in it. The

African seems to be viewed as the object or phenomenon of discussion as opposed to

the subject or theme of discussion. To be Afrocentric is to understand/portray African

people as subjects in human experiences (Asante,l990).

In the final part of Mundimbe's discussion in this chapter, he uses what he

says is: "Frobenius's expression, African Genesis"(p.16). He considers the expansion

of scientific models by social scientists and locality of the theory of the nature of

Africa's invention, and its meaning for African discourse and Africa gnosis.

Mudimbe seems to uphold the European perspective as well as use deprecatory

language toward the African in his choice of references and variety of words. For

example: Mudimbe emphasizes that selective Europe-centered philosophies,

theories, and consequently scientific models and policies developed to suit ---maintain colonial structures, and brought with them interpretations and

designations for original beings and things. In his emphasis, he associates "colonies,"

material value, and the "mother country" with "savages" and "primitives"

(TIOA,p.17). Although the author maintains that the "idea of history" and therefore

the ideology of Africa is rooted in the Western experience and stems from those in

power and the controlling forces, i.e., European economies and structures, he

maintains his reference to the "dependent colonies" and to the African from an other

than Afrocentric perspective.

Mudimbe suggests that levels and types of interpretations of Africa were

distinguished by Western inventors of an "African genesis." He illustrates the

necessity of distinguishing kinds of African knowledge. He cites the academic

achievements of scholars to validate the point of the knowledge of Africa coming from

a European construct. He states that it is a problem that African scholars base their

knowledge and methods on the European constructs. Therefore, he charges the

scholar who seeks a new understanding of human history with posing philosophical

questions of method in the face of contradictory reports.

Although Mudimbe depicts the negative ramifications of European

intervention in Africa and points out the mind control strategies of the European, I

feel that he is writing from a European perspective. It is just a sympathetic

European perspective. The African, as I see it, is not the subject of his discussion.

Although the focus of this analysis is on chapter one of the book where I

indicated dislocation, on the whole, the author concerns himself with various themes

of which, in at least one, I believe he writes Afrocentrically. The themes addressed

include: the foundations of discourse about Africa; the articulation between

missionary language and its African echo or negation, and the ultimate

consequences of this relationship for the anthropologist; a gnosis philosophy on the

order of things in African civilization; the fundamental theme in Blyden's writings;

and anthropology.

The fundamental theme in Blyden's writings is that Africans, from a historical

point of view, constitute a universe apart (from Europe), and have their own history

and traditions. The discussion on Blyden indicates Afrocentric thinking. Without

the benefit of the historical research about African history which we have available

today, there is a discussion of critical issues from an African point of view. In this

part of the text, I believe that the author writes from an Afrocentric perspective.

Funtionally, Mudimbe's general direction of thought leans toward Europe.

Categorically, there is a problem as, Mudimbe deals with themes that focus on the

marginal detachment from "place" that Europeans historical realities have used to

form "universal" theories and concepts.

Although Mundimbe is aware of the deep-seated ethnocentric European structure of

knowledge, whereas in the formal bodies of academic knowledge, only the European

knowledge is considered universal, he works in part within the confines of a

European episteme.

Mudimbe also addresses one way or another the scheme issue in his treatment

of the various recognitions, philosophies and methods, and the systems of knowledge

in and of Africa.

Etymologically, there is another problem; Mundimbe uses words and phrases which

bear derogatory meanings from our perspective as Africologist. Words and phrases

such as, tribe, savage, Bantu, barbarous, etc. are in Mundimbe's book. There is

evidence of dislocation. However, there were instances where Mudimbe places the

African in the subject position rather than object position and writes from an

Afrocentric perspective.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, and in terms of location, I have considered Mundimbe to be bipositional. I believe the following statement Mudimbe makes in the book exemplifies

his position: "Western tradition of science, as well as the trauma of slave trade and

colonization, are part of Africa's present day heritage" (p.79) He believes, as he

states, that he has a right to exploit any part of this heritage (TIOAp.79).

Although, as stated herein, Mudimbe, to my knowledge, does not verbally

declare to be an Afrocentrist, I believe he is a person who pursues things of interest

to the intellect; Mudimbe has authored over 20 books, some on Africa and some in

the "traditional" disciplines, specifically philosophy; sociology; linguistics; and

philology. He received the Herskovits Award for the outstanding English language

scholarly work on Africa for the Invention of Africa. He was the recipient of many

other honors including Senior Fulbright Scholar, University Center of International

Studies, University of Pittsburgh. He is co-author of many books and publications,

and he has written reviews of book on a regular basis. He also speaks several

languages. Therefore, in an intellectual sense, Mudimbe has declared to be an

Afrocentrist, who has worked in many fields, and since 1991 has worked in the field of

Cultural Anthropology, at Duke University. For insight on the Africanist from

"traditional" fields Asante (l992) offers a view:

There are two general fields in which the Afrocentrist

works: cultural/aesthetics and social/behavioral. This

means that the person who declares in an intellectual

sense to be an Afrocentrist commits traditional discipline

suicide because one cannot, to be consistent, remain a

traditional Eurocentric intellectual and an Afrocentrist.

Of course, there are those who might be bi-positional or

multi-positional under given circumstances (Asante,

l992p.17).

In view of the forgoing statements, and under the circumstances, I believe the

"control" element of the environment might influence the author's position. Because

Mudimbe has been trained in the Western tradition, and he is dislocated in this work,

he seeks acceptance from the "dominant culture" (the oppressor) to which this work is

directed. And he also received academic recognition for this work from the oppressor

(honor presented by the U.S. African Studies Assoc.). Academic recognition may

empower Mudimbe to adjust his position toward a more centered approach in

subsequent intellectual work; Therefore, the potential for Mundimbe's attempt at relocation has not been ruled out by this critic. While I am reminded his work is the

product of his social milieu, I presume that this intellectual African may have

positioned himself in such a way as a strategic attempt at impending relocation.

Asante(l990), expounds on the concept of Location:

Relocation occurs when a writer who has been dislocated rediscovers

historical and cultural motifs that serve as sign-posts in the intellectual

or creative pursuit. (Asante, l990p.136).

REFERENCES

Asante, M. (1992). Locating a Text; Implications of Afrocentric Theory. In Bely-Blackshire CA (Ed),

Language and Literature in the African-American Imagination. (pp. 2-20).

Asante, M. K. (1993), Location Theory and African Aesthetics, In Welsh-Asante, K.

(Ed). The African Aesthetic. (pp. 53-62). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Asante, M. K. (August 1992), Afrocentric Systematics. Black Issues in Higher

Education. (pp. 16-22).

Asante, M. K. (l990). Afrocentricity and the Critique of Drama The Western

Journal of Black Studies, 14, 136-141.

Mudimbe, V. Y. (1988). The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the order.

of knowledge, Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press

Welsh-Asante, K. (1993). A Bibliographic Essay on African Aesthetics in The

African Aesthetic. (pp. 249-255). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

También podría gustarte

- Mudimbe and The Invention of Africa (And Latin America) : Which Ways For Pan-Africanism (And Latin-Americanism) Today?Documento8 páginasMudimbe and The Invention of Africa (And Latin America) : Which Ways For Pan-Africanism (And Latin-Americanism) Today?fabriciopereira31Aún no hay calificaciones

- Johs12059 Gurminder Bhamra Contesting Imperial EpistemologiesDocumento9 páginasJohs12059 Gurminder Bhamra Contesting Imperial EpistemologiesSarban MalhansAún no hay calificaciones

- Rob GaylardDocumento18 páginasRob Gaylardmunaxemimosa69Aún no hay calificaciones

- Oral Tradtion Myth and EducationDocumento12 páginasOral Tradtion Myth and EducationSamori Camara100% (1)

- Epistemic Freedom in Africa: Deprovincialization and DecolonizationDocumento42 páginasEpistemic Freedom in Africa: Deprovincialization and DecolonizationClarisbel Gomez vasallo100% (1)

- Claude Sumner and The Quest For An Ethiopian Philosophy: Fasil MerawiDocumento14 páginasClaude Sumner and The Quest For An Ethiopian Philosophy: Fasil MerawiLove IsAún no hay calificaciones

- The Invention of Africa by Mudimbe V.YDocumento20 páginasThe Invention of Africa by Mudimbe V.YAkin DolapoAún no hay calificaciones

- We Are All Postmodernist SnowDocumento27 páginasWe Are All Postmodernist Snowنعمان احسانAún no hay calificaciones

- African Philosophy and The Future of Africa PDFDocumento216 páginasAfrican Philosophy and The Future of Africa PDFSamuel UrbinaAún no hay calificaciones

- pls1502 MCQDocumento7 páginaspls1502 MCQmushAún no hay calificaciones

- ConceptualizingBelongingFinal Summary 1Documento5 páginasConceptualizingBelongingFinal Summary 1Zakaria AbdessadakAún no hay calificaciones

- Thematic Changes in Postcolonial African PDFDocumento10 páginasThematic Changes in Postcolonial African PDFEuphoric NBAún no hay calificaciones

- L5, Leclant El Imperio de KushDocumento23 páginasL5, Leclant El Imperio de KushMarco ReyesAún no hay calificaciones

- Mbembe, On The Power of The False (2002)Documento13 páginasMbembe, On The Power of The False (2002)Francois G. RichardAún no hay calificaciones

- On Achille Mbembe - Subject-Subjection - and Subjectivitythesis - Sithole - TDocumento450 páginasOn Achille Mbembe - Subject-Subjection - and Subjectivitythesis - Sithole - TJosé Manuel Bueso FernándezAún no hay calificaciones

- Ana M Ferreira (2014) Cap 1 - AfrocentricityDocumento12 páginasAna M Ferreira (2014) Cap 1 - Afrocentricitymafy.peguinhoAún no hay calificaciones

- AfrocentricityDocumento10 páginasAfrocentricityArtist MetuAún no hay calificaciones

- The African Value SystemDocumento47 páginasThe African Value SystemEdward MitoleAún no hay calificaciones

- Critical Authors Unit5Documento3 páginasCritical Authors Unit5Rachel LopezAún no hay calificaciones

- Afrocentricity PDFDocumento6 páginasAfrocentricity PDFchveloso100% (2)

- Postcolonial Theory On The Brink: A Critique of Achille Mbembe's On The PostcolonyDocumento20 páginasPostcolonial Theory On The Brink: A Critique of Achille Mbembe's On The PostcolonyJeremy WeateAún no hay calificaciones

- Wai 2015Documento28 páginasWai 2015Paulo Anós TéAún no hay calificaciones

- PhiloDocumento5 páginasPhiloSmoky RubbishAún no hay calificaciones

- Emmanuel Eze in MemoriumDocumento4 páginasEmmanuel Eze in MemoriumbbjanzAún no hay calificaciones

- Distinguishing Between Ontology and DecolonisatioDocumento7 páginasDistinguishing Between Ontology and DecolonisatioThabiso EdwardAún no hay calificaciones

- David Mills, Mustafa Babiker and Mwenda Ntarangwi: Introduction: Histories of Training, Ethnographies of PracticeDocumento41 páginasDavid Mills, Mustafa Babiker and Mwenda Ntarangwi: Introduction: Histories of Training, Ethnographies of PracticeFernanda Kalianny MartinsAún no hay calificaciones

- Makoni - 2004 Western Perspectives On Applied LinguisticsDocumento29 páginasMakoni - 2004 Western Perspectives On Applied Linguisticsxana_sweetAún no hay calificaciones

- Implementing AfrocentricityDocumento17 páginasImplementing AfrocentricityHubert Frederick PierreAún no hay calificaciones

- KMT: in The House of Life. DR M'BRA KouakouDocumento2 páginasKMT: in The House of Life. DR M'BRA KouakouKouame AdjepoleAún no hay calificaciones

- African PhilosophyDocumento8 páginasAfrican Philosophydrago_rossoAún no hay calificaciones

- AfrocentricityDocumento22 páginasAfrocentricityInnocent T SumburetaAún no hay calificaciones

- Africa in The Indian Imagination by Antoinette BurtonDocumento43 páginasAfrica in The Indian Imagination by Antoinette BurtonDuke University PressAún no hay calificaciones

- qt4ph014jj NosplashDocumento31 páginasqt4ph014jj NosplashHanna PatakiAún no hay calificaciones

- Comaroff Comaroff. Theory From The SouthDocumento20 páginasComaroff Comaroff. Theory From The SouthJossias Hélder HumbaneAún no hay calificaciones

- Afrocentricity and Africology. Brooklyn, NY: Universal WriteDocumento4 páginasAfrocentricity and Africology. Brooklyn, NY: Universal WritejakilaAún no hay calificaciones

- Paulin J. Hountondji: Keywords: African Studies Research Knowledge Southern EpistemologiesDocumento11 páginasPaulin J. Hountondji: Keywords: African Studies Research Knowledge Southern EpistemologiescharlygramsciAún no hay calificaciones

- African PhilosophyDocumento6 páginasAfrican Philosophymaadama100% (1)

- African Philosophy and IdentityDocumento18 páginasAfrican Philosophy and IdentityGetye Abneh100% (1)

- On Ethnographic Authority (James Clifford)Documento30 páginasOn Ethnographic Authority (James Clifford)Lid IaAún no hay calificaciones

- Article African LiteraturesDocumento23 páginasArticle African LiteraturesJennifer WheelerAún no hay calificaciones

- Post ColonialismDocumento10 páginasPost ColonialismKhadidjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Shaken Wisdom: Irony and Meaning in Postcolonial African FictionDe EverandShaken Wisdom: Irony and Meaning in Postcolonial African FictionAún no hay calificaciones

- Race and Racial Thinking: Africa and Its Others in Heart of Darkness and Other StoriesDocumento11 páginasRace and Racial Thinking: Africa and Its Others in Heart of Darkness and Other StoriesIOSRjournalAún no hay calificaciones

- Beyond the Doctrine of Man: Decolonial Visions of the HumanDe EverandBeyond the Doctrine of Man: Decolonial Visions of the HumanAún no hay calificaciones

- Indiana University PressDocumento16 páginasIndiana University PresskurkocobAún no hay calificaciones

- Pol Exam Prep 2.0Documento22 páginasPol Exam Prep 2.0bhebhevuyaniAún no hay calificaciones

- The Hermeneutical Paradigm in African Philosophy: NokokoDocumento26 páginasThe Hermeneutical Paradigm in African Philosophy: NokokomarcosclopesAún no hay calificaciones

- Postcolonial Theory and African Literature: by Babatunde E. ADIGUNDocumento15 páginasPostcolonial Theory and African Literature: by Babatunde E. ADIGUNHabes NoraAún no hay calificaciones

- Memories of Africa: Home and Abroad in the United StatesDe EverandMemories of Africa: Home and Abroad in the United StatesAún no hay calificaciones

- The Research Proposal HoubanDocumento10 páginasThe Research Proposal HoubanIbtissam La100% (1)

- Research Skills Course Reseach ProposalDocumento31 páginasResearch Skills Course Reseach ProposalMukuh MthethwaAún no hay calificaciones

- Bodunrin The Question of African PhilosophyDocumento19 páginasBodunrin The Question of African Philosophymichaeldavid0200Aún no hay calificaciones

- José CossaDocumento26 páginasJosé CossaIzabela CristinaAún no hay calificaciones

- Reading Ibn Khaldun in Kampala-Mamdani-2017-Journal - of - Historical - SociologyDocumento20 páginasReading Ibn Khaldun in Kampala-Mamdani-2017-Journal - of - Historical - SociologyGhulam MustafaAún no hay calificaciones

- Cultural and Social Relevance of Contemporary African Philosophy Olukayode Adesuyi Filosofia Theoretica 3-1 2014Documento13 páginasCultural and Social Relevance of Contemporary African Philosophy Olukayode Adesuyi Filosofia Theoretica 3-1 2014FILOSOFIA THEORETICA: JOURNAL OF AFRICAN PHILOSOPHY, CULTURE AND RELIGIONSAún no hay calificaciones

- Anthony Chennells Essential Diversity: Post-Colonial Theory and African Litera Ture1Documento18 páginasAnthony Chennells Essential Diversity: Post-Colonial Theory and African Litera Ture1Stefano A E LeoniAún no hay calificaciones

- How Europe Underdeveloped AfricaDocumento15 páginasHow Europe Underdeveloped AfricaAdaeze IbehAún no hay calificaciones

- Global Migration Perspectives: No. 18 January 2005Documento17 páginasGlobal Migration Perspectives: No. 18 January 2005Diego MarquesAún no hay calificaciones

- Tomàs, Jordi - La Paix Et La Tradition Dans Le Royaume D'oussouye (Casamance)Documento29 páginasTomàs, Jordi - La Paix Et La Tradition Dans Le Royaume D'oussouye (Casamance)Diego MarquesAún no hay calificaciones

- Development and GlobalizationDocumento416 páginasDevelopment and GlobalizationMegan RoseAún no hay calificaciones

- Writing Histories of Contemporary Africa - Stephen EllisDocumento2 páginasWriting Histories of Contemporary Africa - Stephen EllisDiego MarquesAún no hay calificaciones

- Swarup, Ram - Understanding The Hadith 2002Documento230 páginasSwarup, Ram - Understanding The Hadith 2002Diego Marques100% (1)

- Abou, Sélim - The Metamorphoses of Cultural Identity, 1997Documento14 páginasAbou, Sélim - The Metamorphoses of Cultural Identity, 1997Diego MarquesAún no hay calificaciones

- Ajana, Btihaj - Disembodiment and Cyberspace - A Phenomenological Approach 2005Documento12 páginasAjana, Btihaj - Disembodiment and Cyberspace - A Phenomenological Approach 2005Diego MarquesAún no hay calificaciones

- Diane Lewis - Anthropology and ColonialismDocumento23 páginasDiane Lewis - Anthropology and ColonialismDiego MarquesAún no hay calificaciones

- Wasserman, Herman - The Possibilities of ICT For Social Activism in AfricaDocumento22 páginasWasserman, Herman - The Possibilities of ICT For Social Activism in AfricaDiego MarquesAún no hay calificaciones

- Znepolski, Boyan - On The Strenghts and Weaknesses of Academic Social CritiqueDocumento12 páginasZnepolski, Boyan - On The Strenghts and Weaknesses of Academic Social CritiqueDiego MarquesAún no hay calificaciones

- Ahmed, Leila - Western Ethnocentrism and Perceptions of The HaremDocumento15 páginasAhmed, Leila - Western Ethnocentrism and Perceptions of The HaremDiego MarquesAún no hay calificaciones

- Verdery, Ed - Property in Question - Value Transformation in A Global Economy PDFDocumento336 páginasVerdery, Ed - Property in Question - Value Transformation in A Global Economy PDFDiego MarquesAún no hay calificaciones

- Adam Kuper - Lineage TheoryDocumento25 páginasAdam Kuper - Lineage TheoryDiego MarquesAún no hay calificaciones

- Amin, Samir - How Capitalism Went SenileDocumento8 páginasAmin, Samir - How Capitalism Went SenileDiego MarquesAún no hay calificaciones

- State Space ModelsDocumento19 páginasState Space Modelswat2013rahulAún no hay calificaciones

- CATaclysm Preview ReleaseDocumento52 páginasCATaclysm Preview ReleaseGhaderalAún no hay calificaciones

- PDFDocumento3 páginasPDFAhmedraza123 NagdaAún no hay calificaciones

- Magic Bullet Theory - PPTDocumento5 páginasMagic Bullet Theory - PPTThe Bengal ChariotAún no hay calificaciones

- The Chemistry of The Colorful FireDocumento9 páginasThe Chemistry of The Colorful FireHazel Dela CruzAún no hay calificaciones

- Five Reasons Hazards Are Downplayed or Not ReportedDocumento19 páginasFive Reasons Hazards Are Downplayed or Not ReportedMichael Kovach100% (1)

- Smart Door Lock System Using Face RecognitionDocumento5 páginasSmart Door Lock System Using Face RecognitionIJRASETPublicationsAún no hay calificaciones

- I M Com QT Final On16march2016Documento166 páginasI M Com QT Final On16march2016Khandaker Sakib Farhad0% (1)

- Carnegie Mellon Thesis RepositoryDocumento4 páginasCarnegie Mellon Thesis Repositoryalisonreedphoenix100% (2)

- European Asphalt Standards DatasheetDocumento1 páginaEuropean Asphalt Standards DatasheetmandraktreceAún no hay calificaciones

- Acting White 2011 SohnDocumento18 páginasActing White 2011 SohnrceglieAún no hay calificaciones

- Genuine Fakes: How Phony Things Teach Us About Real StuffDocumento2 páginasGenuine Fakes: How Phony Things Teach Us About Real StuffGail LeondarWrightAún no hay calificaciones

- Multinational MarketingDocumento11 páginasMultinational MarketingraghavelluruAún no hay calificaciones

- Img 20150510 0001Documento2 páginasImg 20150510 0001api-284663984Aún no hay calificaciones

- Caring For Women Experiencing Breast Engorgement A Case ReportDocumento6 páginasCaring For Women Experiencing Breast Engorgement A Case ReportHENIAún no hay calificaciones

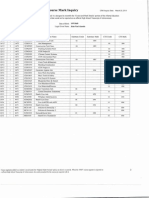

- W.C. Hicks Appliances: Client Name SKU Item Name Delivery Price Total DueDocumento2 páginasW.C. Hicks Appliances: Client Name SKU Item Name Delivery Price Total DueParth PatelAún no hay calificaciones

- View All Callouts: Function Isolation ToolsDocumento29 páginasView All Callouts: Function Isolation Toolsمهدي شقرونAún no hay calificaciones

- (20836104 - Artificial Satellites) Investigation of The Accuracy of Google Earth Elevation DataDocumento9 páginas(20836104 - Artificial Satellites) Investigation of The Accuracy of Google Earth Elevation DataSunidhi VermaAún no hay calificaciones

- Breastfeeding W Success ManualDocumento40 páginasBreastfeeding W Success ManualNova GaveAún no hay calificaciones

- Contemporary Strategic ManagementDocumento2 páginasContemporary Strategic ManagementZee Dee100% (1)

- Borges, The SouthDocumento4 páginasBorges, The Southdanielg233100% (1)

- Application of The Strain Energy To Estimate The Rock Load in Non-Squeezing Ground ConditionDocumento17 páginasApplication of The Strain Energy To Estimate The Rock Load in Non-Squeezing Ground ConditionAmit Kumar GautamAún no hay calificaciones

- Instant Download Business in Action 7Th Edition Bovee Solutions Manual PDF ScribdDocumento17 páginasInstant Download Business in Action 7Th Edition Bovee Solutions Manual PDF ScribdLance CorreaAún no hay calificaciones

- Worst of Autocall Certificate With Memory EffectDocumento1 páginaWorst of Autocall Certificate With Memory Effectapi-25889552Aún no hay calificaciones

- Caterpillar Cat C7 Marine Engine Parts Catalogue ManualDocumento21 páginasCaterpillar Cat C7 Marine Engine Parts Catalogue ManualkfsmmeAún no hay calificaciones

- Full Project LibraryDocumento77 páginasFull Project LibraryChala Geta0% (1)

- Sample REVISION QUESTION BANK. ACCA Paper F5 PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENTDocumento43 páginasSample REVISION QUESTION BANK. ACCA Paper F5 PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENTAbayneh Assefa75% (4)

- Arithmetic QuestionsDocumento2 páginasArithmetic QuestionsAmir KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Best Mutual Funds For 2023 & BeyondDocumento17 páginasBest Mutual Funds For 2023 & BeyondPrateekAún no hay calificaciones

- The Linguistic Colonialism of EnglishDocumento4 páginasThe Linguistic Colonialism of EnglishAdriana MirandaAún no hay calificaciones