Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

The Intergenerational Transmission of Corporal Punishment

Cargado por

Andrew KendallDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

The Intergenerational Transmission of Corporal Punishment

Cargado por

Andrew KendallCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Pergamon

Child Abuse& Neglect,Vol. 19, No. II, pp. 1323-1335, 1995

Copyright 1995 ElsevierScience Ltd

Printed in the USA. All rightsreserved

0145-2134/95 $9.50 + .00

0145-2134(95)00103-4

THE INTERGENERATIONAL TRANSMISSION OF

CORPORAL PUNISHMENT: A COMPARISON OF

SOCIAL LEARNING AND TEMPERAMENT MODELS

ROBERT T. M U L L E R

Psychology Department, University of Massachusetts at Boston, Boston, MA, USA

JOHN E . H U N T E R AND G A R Y S T O L L A K

Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA

Abstract--This family study examined two models regarding the intergenerational transmission of corporal punishment. The model based on social learning assumptions asserted that corporal punishment influences aggressive child

behavior. The model based on temperament theory suggested that aggressive child behavior impacts upon parental

use of corporal punishment. Participants were 1,536 parents of 983 college students. Corporal punishment was assessed

from father, mother, and child perspectives. Path analyses revealed that the social learning model was most consistent

with the data.

Key Words--Child abuse, Child maltreatment, Corporal punishment, Temperament, Social learning.

INTRODUCTION

O N E O F T H E most c o m m o n l y reported characteristics o f physically punitive parents is that

o f history o f maltreatment. It is often asserted that there is a high concordance between being

a recipient of severe corporal punishment and carrying out similar behavior on o n e ' s own

children (e.g., Carroll, 1977; Gillespie, Seaberg, & Berlin, 1977; Isaacs, 1981; L i e h - M a k ,

Chung, & Liu, 1983; Webster-Stratton, 1985), the so-called " c y c l e o f a b u s e " ( K e m p e &

Kempe, 1978). It is important to note that the " c y c l e o f a b u s e " m a y be s o m e w h a t overstated.

Quinton and Rutter (1984a, 1984b) studied parents with serious and persistent parenting difficulties. O f these parents, 61% had experienced four or more childhood adversities such as

frequent beatings, while 16% of controls suffered such adversities. Kaufman and Z i g l e r (1987)

noted that only one third o f adults who had received rigorous corporal punishment went on

to do so with their own children. Furthermore, Simons, Whitbeck, Conger, and Chyi-In (1991)

found correlations b e l o w .31 between grandparent harsh discipline and parent harsh discipline.

C o m i n g out o f the research tradition that e m p h a s i z e d the intergenerational transmission o f

p h y s i c a l l y punitive parenting were several studies demonstrating the relationship between

experiencing corporal punishment in o n e ' s childhood and manifesting subsequent aggressive

This research was funded by fellowships granted to the first author from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research

Council of Canada (grants 452-89-0451 and 452-90-0226).

Received for publication September 15, 1994; final revision received April 14, 1995; accepted April 17, 1995.

Reprint requests should be addressed to Robert T. Muller, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Psychology, Psychology

Department, University of Massachusetts at Boston, 100 Morrissey Boulevard, Boston, MA 02125-3393.

1323

1324

R. T. Muller, J. E. Hunter, and G. Stollak

behaviors. These investigations typically have assumed the operation of social learning principles. In that view, aggressive actions and use of corporal punishment are behaviors learned

from one's parents. Several studies indicated that children who receive severe corporal punishment are more likely to demonstrate aggressive responses toward others (e.g., McCord, 1988;

Trickett & Kuczynski, 1986). Kratcoski and Kratcoski (1982) found formerly maltreated adolescents were more likely to direct violence toward significant others. Muller, Fitzgerald,

Sullivan, and Zucker (1994) found that severe physical punishment of children predicted

those children's aggressiveness among alcoholic families. Simons and colleagues (199 I) found

evidence for a path model suggesting that harsh parental discipline would lead to a hostile

personality in the survivor, predicting survivor's use of harsh discipline.

All of the studies on aggressive behavior cited above make certain implicit assumptions.

They are based on an environmental model of behavior. Specifically, it is assumed that if

physically punitive parents end up with aggressive children, it is because the child has learned

some pattern of response. It may be suggested, alternatively, that the child had a predisposition

toward aggressive behavior, and that the punitive parental behavior is a response to the child.

Several investigations suggested that children that are more difficult to manage end up

receiving greater levels of severe corporal punishment. Smith (1984) proposed that verbally

aggressive children may be at high risk for physical punishment. Investigating 570 German

families, Engfer and Schneewind (1982) found that having a child that is rated by the parent

as difficult to handle, and who manifests conduct disorder problems in school (problem child)

is the best predictor of mothers' use of corporal punishment. Herrenkohl, Herrenkohl, and

Egolf (1983) studied case records of 825 physical maltreatment incidents, occurring in 328

families. Parents were asked for the reason the incident took place. Parents cited child misbehaviors such as refusals, fighting, "immoral" behaviors, and aggressiveness as leading to

greater use of severe corporal punishment.

The studies cited above assume that corporal punishment can be a response to aggressive child

behavior, rather than its cause. The two sets of studies described here use very different assumptions

to explain the same associations. However, these prior studies have failed to test the causal pathway

of the intergenerational transmission of corporal punishment and aggressive behavior.

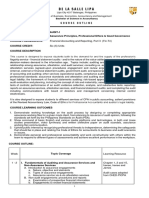

In Figure 1, two models with very different assumptions are presented as explanations of

the intergenerational transmission of corporal punishment. Model A assumes that aggressive

behavior is an individual difference characteristic that is based in temperament. As such,

"parent's lifetime aggressive behavior" is the initial variable in the causal chain. Further, the

model posits that aggressive behavior is a factor that leads to the response of corporal punishment on the part of one's parents. Thus, for people who are currently parents, their former

aggressive behaviors influenced the likelihood of their receiving corporal punishment from

their own parents. Children's aggressive behaviors influenced the likelihood of their receiving

corporal punishment from their own parents.

Model B proposes directly the opposite, and it assumes the operation of social learning

principles. The model asserts that an individual's tendency to manifest aggressive behavior

across the lifespan is a consequence of the observational learning that takes place when

receiving corporal punishment from the parents. Thus, for people who are currently parents,

greater levels of corporal punishment given by their own parents influenced greater manifestation of their own aggressive behaviors. Similarly, children who received corporal punishment

from their parents are more likely to manifest subsequent aggressive behaviors.

It is important to note that these two models are based on assumptions that are diametrically

opposed. They represent philosophical positions (temperament and social learning theory) that

are on two ends of a spectrum. The purpose of this research was to assess the legitimacy of

these two contrasting models, and to assess the extent to which each of these two positions

contributes in greater measure to the child maltreatment process.

Models of corporal punishment

1325

MODEL A

MODEL B

Figure 1. Two models of the intergenerational transmission of corporal punishment.

The data were gathered on 983 families, allowing for capitalization on multiple perspectives.

The fathers, mothers, and college-age children each reported the extent of corporal punishment

used upon the child. Analyses made use of these multiple perspectives in coding variables.

METHOD

Participants

Parents consisted of 1,536 persons (732 fathers, 804 mothers), who were parents of 983

college students. Median age was 47 years. Ethnic background for Caucasian, Black, and

Hispanic subjects was 90.4%, 3.6%, and 1.3% respectively. The largest religious categories

endorsed were Roman Catholic (n = 689), Presbyterian (n = 156), and Lutheran (n = 145).

The median respondent considered him/herself to be "fairly" religious. Average level of

schooling completed was "some high school." The modal occupation category endorsed was

"skilled manual employee."

College students consisted of 983 participants (295 males, 688 females) in psychology

classes at Michigan State University. Median age was 18.0 years. Ethnic background for

Caucasian, Black, and Hispanic subjects was 86.8%, 6.1%, and 1.9% respectively. The largest

religious categories endorsed were Roman Catholic (n = 414), Presbyterian (n = 88), and

Lutheran (n = 74). The median respondent considered him/herself to be "somewhat" religious.

Average level of schooling completed was "some college." The modal occupation category

endorsed was "clerical or sales worker, technician, or proprietor of a very little business."

1326

R.T. Muller, J. E. Hunter, and G. Stollak

Materials

Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS; Straus, 1989; Straus & Gelles, 1989). In order to provide an

indication of the respondent's childhood experience with physically punitive parenting, an

adapted version of the CTS was used. Several items were taken from the Assessing Environments III Questionnaire (AEIII; Berger, Knutson, Mehm, & Perkins, 1988). Subjects were

asked to indicate their parents' behaviors or tactics toward them in conflict situations. The

measure used in this study listed 16 ways to deal with conflict ranging from discussing the

issue calmly to using a knife or gun. Conflict tactics were reported separately for each parent.

Frequencies were reported on a 4-point intensity scale ranging from " n e v e r " to "three times

or more." All subjects (college students and parents) were asked to indicate each of their own

parents' conflict tactics during the course of their entire childhood (32 items in total). Parents

were also asked to rate their own conflict tactics toward their own children. Thus, the Conflict

Tactics Scales were used to define two variables. They are "parent's corporal punishment

from own parents" and "parent's use of corporal punishment upon student."

There is some evidence in prior literature that given certain conditions, self-report questionnaires may be a valid method of reporting histories of severe physical punishment. The research

of Berger and colleagues (1988) demonstrated that if parental punitiveness is broken down in

terms of specific behaviors, subjects are able to provide self-reports that are reliable and valid

measures of their childhood experiences of corporal punishment. Similar results were found

in sexual abuse (Elliot & Briere, 1992).

The CTS was used in such a manner, for the purposes of assessing childhood experience

of child maltreatment in a study by Muller, Caldwell, and Hunter (1994). That is, prior parental

punitiveness was broken down in terms of specific behaviors. The authors demonstrated a

reliability coefficient of r = .77 for the CTS. Also, the construct validity of the CTS has been

reasonably well-documented. For example, there is broad consensus that stress increases the

risk of child maltreatment. Research using the CTS has yielded results consistent with that

theory (Straus, 1989).

Using the CTS, the extent to which each parent used corporal punishment upon the child

was evaluated from multiple perspectives (the parents' and the children's).

The Aggressive Behavior Scale (ABS), developed for this study. This scale measures lifetime

aggressive behavior. One 9-item subscale measured the respondent's history of aggressive

behavior above age 11. A second 10-item subscale measured the respondent's aggressive

behavior below age 11. Many items from the first subscale were derived from the Antisocial

Behavior Checklist (Zucker, Noll, & Fitzgerald, 1986), for which Fitzgerald, Jones, Maguin,

Sullivan, Zucker, and Noll (1991) reported reliability coefficients of r = .90 among prison

inmates, and r = .80 to .85 for undergraduate students. Many items on the second subscale

were derived from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983) and

the Child Behavior Rating Scale (CBRS; Hops, 1985); one item was taken from Malarnuth,

Sockloskie, Koss, and Tanaka (1991).

The ABS listed various behaviors, and subjects indicated the number of times they acted

in such a fashion ranging from 0 to 3 or more occurrences, in the respondent's life. Sample

items from the first subscale include the following: "Been arrested for any nontraffic police

offense" and "Said very cruel or humiliating things to someone." Sample items from the

second subscale include: "Teased other children" and "Destroyed property such as tearing

books or breaking toys."

The Demographic Questionnaire (DQ), developed for this study. This questionnaire asked

subjects about their parents' occupations (Hollingshead Index; Mueller & Parcel, 1981), educa-

Models of corporal punishment

1327

tion, and income. Subjects were asked to provide similar socioeconomic information about

themselves. They were asked about their age, their gender, and their racial and religious

backgrounds.

Scales

Constructs hypothesized to be unidimensional were tested using confirmatory factor analysis

(Anderson & Gerbing, 1982; Hunter & Gerbing, 1982). The full confirmatory factor analyses

for these data are not included here in the interest of length. However, they may be found in

Muller (1993). The final clusters from the confirmatory factor analyses are displayed in Tables

1 and 2 for parents and children respectively. Tables present the scale means, standard deviations, and standardized alpha reliabilities.

Procedure

For extra credit, 983 psychology undergraduates elected to sign up in the "Family Attitudes

Survey." In group format, students received three envelopes. Envelope 1 contained the Conflict

Tactics Scales (CTS) (referring to the child's father and mother separately); also, it contained

the Aggressive Behavior Scale (ABS), and the Demographic Questionnaire (DQ). Envelopes

2 and 3 respectively contained the complete packet of questionnaires for the respondent's

father and mother to complete. Each of those packets contained the Conflict Tactics Scales

(CTS) (referring to the parent's own father and mother separately); also, they contained the

Aggressive Behavior Scale (ABS), and the Demographic Questionnaire (DQ).

Envelopes 1 - 3 had the same ID number. Students were informed of the voluntary, confidential, and anonymous nature of this research. They were told that they may elect to discontinue

participation at any time, and that they indicate their voluntary consent to participate by

returning the completed questionnaires. Next, they were invited to open the first envelope and

complete the enclosed measures on the bubble sheets provided. Responses were collected.

Students were then informed that they have earned credit for research participation. Next, they

were told that if they wish, they may continue participation for further credit by addressing

the two envelopes (each containing a set of questionnaires for their parents to complete) and

returning these materials to the researchers for mailing. They were told that their parents will

have no access to information the students have given us so far, that their parents will receive

no other information other than what is in the packet, that all parents are receiving these

questionnaires regardless of what the children say about them, that they should feel free to

look through the packet of questionnaires to make sure they feel comfortable with the questionnaires, and that the only thing linking them to their parents is a random ID number.

Parents receiving questionnaires were also informed of the voluntary, confidential, and

anonymous nature of this research, that they may discontinue participation at any time, that

Table 1. Scale Means, Standard Deviations, and Alpha Reliabilities for Parents

Scale

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Conflict Tactics

ConflictTactics

ConflictTactics

Conflict Tactics

ConflictTactics

Conflict Tactics

AggressiveBehavior Scale

Hollingshead Index

Construct Measured

SD

Alpha

Minor Violence from Own Father

Minor Violence from Own Mother

Very Severe Violence from Own Father

Very Severe Violence from Own Mother

Minor Violence Toward Own Child

Very Severe Violence Toward Own Child

Aggressive Tendencies

Socio-econ.3mic Status

.82

.87

.09

.06

.56

.04

.95

5.48

.79

.82

.32

.25

.23

.10

.58

1.11

.72

.72

.81

.82

.63

.67

.79

.76

1328

R . T . Muller, J. E. Hunter, and G. Stollak

Table 2. Scale Means, Standard Deviations, and Alpha Reliabilities for College-Age Children

Scale

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Conflict Tactics

Conflict Tactics

Conflict Tactics

Conflict Tactics

Aggressive Behavior Scale

Hollingshead Index

Construct Measured

SD

Alpha

Minor Violence from Own Father

Minor Violence from Own Mother

Very Severe Violence from Own Father

Very Severe Violence from Own Mother

Aggressive Tendencies

Socio-economic Status

.79

.82

.07

.08

1.06

5.80

.82

.84

.24

.30

.71

1.04

.77

.78

.82

.75

.81

.76

all parents involved in the study are completing identical questionnaires, that parents and

children will be given no information about the responses made by the other, and that they

indicate their voluntary consent to participate by returning the completed questionnaire. Parents

completed answers on the bubble sheets provided in each packet. Packets had an accompanying

self-addressed, business reply envelope. All students received full research participation credit

regardless of the extent of their parents' participation.

Following family participation, students were given a location and time to pursue in order

to receive a full explanation of the results of this study. This consisted of a summary distributed

by the MSU psychology department, and a phone number to call if they had further questions.

Students were encouraged to share this handout with their parents.

Response Rates

The response rates are presented separately for fathers and mothers, and furthermore separately for parents on the two extreme ends of the corporal punishment scale. Parents at either

end of the scale will be referred to as " a b u s i v e " and "nonabusive." Parents were defined as

abusive if the child reported that the parent carried out any of the behaviors from the " V e r y

Severe Violence Index" of the CTS (Straus, 1989; Straus & Gelles, 1989). Response rates

were calculated separately for the abusive and nonabusive groups in order to confirm the

assumption that both groups of parents were equally likely to participate.

First, we calculated the percentage of students who agreed to have questionnaires sent to

their parents. Out of a base of 983 students and 1,928 parents, the percentage of students

allowing the participation of their fathers and mothers were 86.2% and 91.9% respectively.

Consequently, the total number of parents mailed questionnaires was n = 1,750. Among

abusive and nonabusive fathers, the percentages were 81.1% and 88.7% respectively. Among

abusive and nonabusive mothers, the percentages were 94.1% and 91.7% respectively.

Next, of parents who were mailed questionnaires, what proportion completed and returned

them? For fathers and mothers the percentages were 88.3% and 90.9% respectively. The total

number of parents who returned completed questionnaires was n = 1,569. Among abusive

and nonabusive fathers, the percentages were 84.2% and 89.5% respectively. Among abusive

and nonabusive mothers, the percentages were 82.1% and 92.1% respectively. Thus, there did

not appear to be a systematic bias in which students and parents from abusive homes elected

not to participate.

It is important to note that some parents and students chose not to participate. Since data were

only collected on those who did choose to participate, information on subject characteristics is

limited to that group.

RESULTS

The goal of these analyses was to assess the extent to which the two models (A & B)

demonstrated consistency with the data. In this study, we chose a method of analysis that was

1329

Models of corporal punishment

Table 3. Correlations Used in the Path Analyses (Father and Child Data)

Fathers (n = 732)

Measure

I.

2.

3.

4.

Father's Corporal Punishment from Own Parents

Father's Lifetime Agressive Behavior

Father's use of Corporal Punishment Upon Child

Child's Lifetime Aggressive Behavior

1.00

.45

.40

.03

1.00

.34

.17

1.00

.36

1.00

Note. For all correlations in this table (except for r = .03), p < .05. Variables 1 and 2: Father as data source. Variable

3: Father and child as data sources. Variable 4: Child as data source.

based upon the work of Anderson and Gerbing (1982). This approach differs from the more

popular Full Information Maximum Likelihood method (LISREL) developed by Joreskog

(1978). Our method consisted of a two-step approach in which confirmatory factor analyses

were conducted prior to the path analyses. For the confirmatory factor analyses, cluster solutions

were sought by successively repartitioning the items until the criteria of unidimensionality

was achieved for each cluster. Clusters were considered unidimensional only when they met

criteria for both internal and external consistency. One of the advantages of this technique

over LISREL is that measurement error is removed prior to executing the path analysis.

Following the confirmatory factor analyses, path analyses using ordinary least squares were

conducted. A detailed discussion of these statistical issues is beyond the scope of this article,

and the interested reader is directed toward Anderson and Gerbing (1982).

Several path analyses were carried out. The path coefficients were estimated using the

traditional procedure of ordinary least squares. The correlations derived from the confirmatory

factor analyses were used as input into the path analysis program. Correlations were corrected

for attenuation. The relevant correlations are presented in Tables 3, 4, and 5. The correlations

are presented separately for fathers, mothers, and all parents (fathers and mothers). Since the

data used in these analyses were gathered for several members of the same family, it was

possible to use multiple perspectives to define certain variables. In particular, the extent of

corporal punishment used upon the child was assessed from the father's, mother's, and child's

points of view. Thus, for Tables 3, 4, and 5, extent of corporal punishment used upon the

child was calculated using these multiple perspectives. At the bottom of these tables are listings

of whose perspectives went into defining each variable.

Path Analyses Results

The results of the path analyses are presented for fathers first. The findings indicated that

Model A was not consistent with the data. The chi square test for overall goodness of fit

Table 4. Correlations Used in the Path Analyses (Mother and Child Data)

Mothers (n = 804)

Measure

1.

2.

3.

4.

Mother's Corporal Punishment from Own Parents

Mother's Lifetime Aggressive Behavior

Mother's Use of Corporal Punishment Upon Child

Child's Lifetime Aggressive Behavior

1.00

.55

.46

.15

1.00

.48

.20

1.00

.34

1.00

Note. For all correlations in this table, p < .05. Variables I and 2: Mother as data source. Variable 3: Mother and

child as data sources. Variable 4: Child as data source.

1330

R. T. Muller, J. E. Hunter, and G. Stollak

Table 5. Correlations Used in the Path Analyses (Parent and Child Data)

Parents (n = 1536)

Measure

I. Parent's Corporal Punishment from

Own Parents

2. Parent's Lifetime Aggressive

Behavior

3. Parent's Use of Corporal Punishment

4. Child's Lifetime Aggressive

Behavior

1.00

.55

1.00

.36

.11

.29

.20

1.00

.50

1.00

Note. For all correlations in this table, p < .05. Variables 1 and 2: Father and Mother as data sources. Variable 3:

Father, Mother, and Child as data sources. Variable 4: Child as data source.

indicated a significant difference between the model and the data X2(2) = 14.39, p < .001.

For Model B, the chi-square test for overall goodness of fit did not indicate a significant

difference between the model and the data X2(2) -- 3.83, p < . 147. The correlations and path

coefficients for these path analyses are shown in Figure 2. Using the goodness of fit technique

discussed in Bentler and Bonett (1980), it was possible to assess the extent to which Model

B represented an improvement over Model A. For fathers, Model B represented an improvement

as follows: NFI = .73; NNFI = .85.

Next, the results of the path analysis are presented for mothers. The findings indicated that

JIJlODEL A

MODEl. B

I~37)

Figure 2. The path models for fathers with correlations and path coefficients between constructs. [ ] = correlation;

( ) = path coefficient.

Models of corporal punishment

1331

Model A was not consistent with the data. The chi-square test for overall goodness of fit

indicated a significant difference between the model and the data X2(2) = 9.53, p < .009. For

Model B, the chi-square test for overall goodness of fit did not indicate a significant difference

between the model and the data X2(2) = .30, p < .860. The correlations and path coefficients

for these path analyses are shown in Figure 3. The Bentler and Bonett (1980) goodness of fit

index indicated that for mothers, Model B represented an improvement over Model A as

follows: N F I = .97; N N F I = 1.23.

The results of the path analysis are presented for parents in general (i.e., fathers and mothers

combined). The findings indicated that Model A was not consistent with the data. The chi

square test for overall goodness of fit indicated a significant difference between the model and

the data X2(2) = 9.76, p < .008. For Model B, the chi square test for overall goodness of fit

did not indicate a significant difference between the model and the data X2(2) = 1.92, p <

.382. The correlations and path coefficients for these path analyses are presented in Figure 4.

The Bentler and Bonett (1980) goodness of fit index indicated that for parents in general,

Model B represented an improvement over Model A as follows: N F I = .80; N N F I = 1.01.

DISCUSSION

The result of this project indicated the following. When using classic goodness of fit indices,

Model B represented greater consistency with the data than did Model A. While the results

may have been somewhat stronger for mothers than for fathers, both were in the same direction.

MODEL A

MODEL B

Figure 3. The path models for mothers with correlations and path coefficients between constructs. [ ] = correlation;

( ) = path coefficient.

1332

R. T. Muller, J. E. Hunter, and G. Stollak

\~ ~.29"1(.20")~

MODEL B

Figure 4. The path models for parents (mothers and fathers) with correlations and path coefficients between

constructs. [ ] = correlation; ( ) = path coefficient.

This indicates that the assumptions made in the social learning approach to the intergenerational

transmission of corporal punishment are consistent with the data gathered in the current study.

A number of prior investigations of the intergenerational transmission of corporal punishment, have assumed the underlying operation of social learning principles (Kratcoski & Kratcoski, 1982; Malamuth et al., 1991; McCord, 1988; Muller et al., 1994; Simons et al., 1991;

Trickett & Kuczynski, 1986). However, these assumptions had generally not been tested

directly against alternate perspectives. The current investigation directly tested and provided

some corroboration for the social learning position.

One may ask what the theoretical implications of this study are. The current investigation

does not dispute temperament theory. There is clear evidence from previous studies that infants

display significant individual differences at birth. Among the most significant of these studies

was Thomas and Chess's (1977) longitudinal (over 25 year) investigation. The authors were

able to define several dimensions of child behavior that differentiated among children as young

as 2 to 3 months of age, and were assumed to reflect biologically based characteristics.

The current study does not refute the concept of temperament p e r se. However, this investigation does suggest that temperament does not adequately explain the process by which corporal

punishment is passed on intergenerationally.

Theoretically, one might argue that the child maltreatment process is not due either to

temperament or to social learning factors, but rather child maltreatment is a dynamic process

in which both behavioral components play a significant role. The position would assert that

there is a dynamic interaction between biological variables and social environment upon

behavior. This more integrative approach can be corroborated through the use of longitudinal

data. Using several waves of data collection, one could examine simultaneously the process

by which aggressive chiId temperament and parental use of corporal punishment unfolds over

time. For example, aggressive child behavior at time 1 might predict parental use of corporal

punishment at time 2, which might predict aggressive child behavior at time 3.

Models of corporal punishment

1333

The findings of this investigation are also interesting when they are linked to some of the

earlier research on child victim blame. Muller, Caldwell, and Hunter (1993) gave physically

abusive parenting scenarios to 897 college students. These scenarios varied in the extent to

which the children demonstrated provocative (aggressive) behaviors. The authors found that

when responding to such vignettes, subjects blamed provocative children much more than

nonprovocative. Linking the current study to Muller and colleagues (1993), one may speculate

that children growing up in abusive homes may be in a particularly difficult bind, where they

learn from parents to act out in an aggressive manner, but then are blamed by others for their

behaviors.

Clinical relevance. The theoretical issues raised in this research may have bearing upon clinical

practice. Corroboration of the social learning view, suggests that prevention and treatment of

child maltreatment should have far reaching effects. Helping parents change their behaviors

should lead to changes in child behavior down the road.

A clinician assuming the social learning view may be concerned with training parents in

alternative disciplining methods, and helping parents develop strategies to manage their children, other than losing control. Such a therapist may assume that the parents' children would

otherwise pick up the parents' problematic coping methods, and that the parents could learn

new ways to manage intense affect, and model those to the children. The intervention may be

a cognitive-behavioral anger management therapy group for parents; or the clinician may

utilize a solution-based "problem-solving" approach such as that advocated by Haley (1987).

A number of clinical psychologists have developed treatment programs in order to prevent

the practice of child maltreatment or to treat families in which child abuse takes place. In one

such program, Wolfe (1991) established an approach designed to address a broad population

with a wide variety of parenting deficits. In his program, parents are taught child management

and parental sensitivity techniques. They are also encouraged to take part in the establishment

of peer group supports. Parents are educated on methods of discipline and anger management

as well. In a study conducted by Olds and Henderson (1989), the authors put together a home

visitation program grounded in ecological theory. Parental involvement began during pregnancy

and continued into infancy. Parent education by nurses was an important component. Informal

supports were increased for mothers. Also, parents were educated regarding services such as

planned parenthood.

Limitations and strengths of this project. First, this study did not utilize a wide range of racial

and ethnic groups. Black parents comprised only 3.6% of the parent sample. Only a handful

of parents were Native American. Consequently, results should be limited primarily to Caucasians. Also, representation by Roman Catholic subjects was high. Cross-cultural replication is

recommended.

Second, the data were collected by means of self-report questionnaires. Since subjects were

conveying information that was of a relatively personal nature, one may posit that they might

have been more honest in interview settings (Wyatt & Peters, 1986). However, others disagree

with this position (Berger et al., 1988). Furthermore, in the current study, self-report data were

collected from multiple sources. This allowed for the variable of corporal punishment toward

the child to be defined from more than one perspective. The majority of research studies in

this area have defined this variable from only one perspective, which is problematic (Femina,

Yeager, & Lewis, 1990; Robins, 1966).

A third limitation is that the current study was cross-sectional in design. Consequently, it

is somewhat limited in the extent to which it can address questions of causality. The technique

of path analysis was used in order to partially circumvent that limitation. With cross-sectional

data on individual difference variables, it is more appropriate to make causal interpretations

1334

R. T. Muller, J. E. Hunter, and G. Stollak

with path analysis than with traditional techniques, such as analysis of variance or multiple

regression. Furthermore, with cross-generational data (as in the current study), frequently there

is a natural ordering to many of the variables. Nevertheless, use of longitudinal data in the

context of a path analysis, would allow for the greater naturalness of individual difference

(nonexperimental) variables along with the greater ability to draw causal inferences from the

data. It is suggested that the current study be replicated using a longitudinal design.

Several strengths are worth note. The first of these is the large sample size. The sample of

1,536 parents meant that the standard error of correlation coefficients was very low, yielding

greater confidence in the accuracy of rs. Second, this study investigates the issue of corporal

punishment not just among mothers, but among fathers too. Several theorists (Phares, 1992;

Phares & Compas, 1992) have argued that fathers are dramatically under-represented in clinical

child and adolescent research. The current study allows for a comparison of findings for fathers

with those for mothers, in a way that many previous studies do not.

REFERENCES

Achenbach, T., & Edelbrock, C. (1983). Manual for the child behavior checklist and revised child behavior profile.

New York: Queen City Printers.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1982). Some methods for respecifying measurement models to obtain unidimensional construct measurement. Journal of Marketing Research, 19, 453-460.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures.

Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588-606.

Berger, A. M., Knutson, J. F., Mehm, J. G., & Perkins, K. A. (1988). The self-report of punitive childhood experiences

of young adults and adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 12, 251-262.

Carroll, J. C. (1977). The intergenerational transmission of family violence: The long-term effects of aggressive

behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 3, 289-299.

Elliot, D. M., & Briere, J. (1992). Sexual abuse trauma among professional women: Validating the trauma symptom

checklist-40 (TSC-40). Child Abuse & Neglect, 16, 391-398.

Engfer, A., & Schneewind, K. A. (1982). Causes and consequences of harsh parental punishment: An empirical

investigation in a representative sample of 570 German families. Child Abuse & Neglect, 6, 129-139.

Femina, D. D., Yeager, C. A., & Lewis, D. O. (1990). Child abuse: Adolescent records vs. adults recall. ChildAbuse &

Neglect, 14, 227-231.

Fitzgerald, H. E., Jones, M-A., Maguin, E., Sullivan, L. A., Zucker, R. A., & Noll, R. B. (1991). The antisocial

behavior inventory: Assessing antisocial behavior in alcoholic and nonalcoholic adults. Unpublished manuscript,

Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI.

Gillespie, D. F., Seaberg, J. R., & Berlin, S. (1977). Observed causes of child abuse. Victimology, 2, 342-349.

Haley, J. (1987). Problem-solving therapy (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Herrenkohl, R. C., Herrenkohl, E. C., & Egolf, B. P. (1983). Circumstances surrounding the occurrence of child

maltreatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 424-431.

Hops, H. (1985). The child behavior rating scale. Unpublished manuscript. Oregon Research Institute, Eugene, OR.

Hunter, J. E., & Gerbing, D. W. (1982). Unidimensional measurement, second order factor analysis, and causal

models. In B. M. Straw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 267-320).

Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

lsaacs, C. (1981). A brief review of the characteristics of abuse-prone parents. Behavior Therapist, 4, 5-8.

Joreskog, K. G. (1978). Structural analysis of covariance and correlation matrices. Psychometrika, 43, 444-447.

Kaufman, J., & Zigler, E. (1987). Do abused children become abusive parents? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry,

57, 186-192.

Kempe, R. S., & Kempe, C. H. (1978). Child abuse. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kratcoski, P. C., & Kratcoski, L. D. (1982). The relationship of victimization through child abuse to aggressive

delinquent behavior. Victimology: An International Journal, 7, 199-203.

Lieh-Mak, F., Chung, S. Y., & Liu, Y. W. (1983). Characteristics of child battering in Hong Kong: A controlled

study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 142, 89-94.

Malamuth, N. M., Sockloskie, R. J., Koss, M. P., & Tanaka, J. S. (1991). Characteristics of aggressors against women:

Testing a model using a national sample of college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59,

670-681.

McCord, J. (1988). Parental behavior in the cycle of aggression. Psychiatry, 51, 14-23.

Muller, R. T. (1993). Shame and aggressive behavior in corporal punishment. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation.

Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI.

Models of corporal punishment

1335

Muller, R. T., Caldwell, R. A., & Hunter, J. E. (1993). Child provocativeness and gender as factors contributing to

the blaming of victims of physical child abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 17, 249-260.

Muller, R. T., Caldwell, R. A., & Hunter, J. E. (1994). Factors predicting the blaming of victims of physical child

abuse or rape. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 26, 259-279.

Muller, R. T., Fitzgerald, H. E., Sullivan, L. A., & Zucker, R. A. (1994). Social support and stress factors in child

maltreatment among alcoholic families. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 26, 438-461.

Mueller, C. W., & Parcel, T. L. (1981). Measures of socioeconomic status: Alternatives and recommendations. Child

Development, 52, 13-30.

Olds, D. L., & Henderson, C. R. (1989). The prevention of maltreatment. In D. Cicchetti & V. Carlson (Eds.), Child

maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect (pp. 722-763).

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Phares, V. (1992). Where's poppa? The relative lack of attention to the role of fathers in child and adolescent

psychopathology. American Psychologist, 47, 656-664.

Phares, V., & Compas, B. E. (1992). The role of fathers in child and adolescent psychopathology: Make room for

daddy. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 387-412.

Quinton, D., & Rutter, M. (1984a). Parents with children in care: 1. Current circumstances and parenting. Journal of

Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 25, 211-229.

Quinton, D., & Rutter, M. (1984b). Parents with children in care: 11. Intergenerational continuities. Journal of Child

Psychology and Psychiatry, 25, 231-250.

Robins, L. N. (1966). Deviant children grown up. Baltimore, MD: Wilkins.

Simons, R. L., Whitbeck, L. B., Conger, R. D., & Chyi-in, W. ( 1991 ). Intergenerational transmission of harsh parenting.

Developmental Psychology, 27, 159-171.

Smith, J. E. (1984). Nonaccidental injury to children: A review of behavioral interventions. Behavior Research and

Therapy, 22, 331-347.

Straus, M. A. (1989). Manual for the Conflict Tactics Scales. Durham, NH: Family Research Laboratory.

Straus, M. A., & Gelles, R. J. (1989). Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence

in 8,145 families. New Brunswick, N J: Transaction Books.

Thomas, A., & Chess, S. (1977). Temperament and development. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Trickett, P. K., & Kuczynski, L. (1986). Children's misbehaviors and parental discipline strategies in abusive and

nonabusive families. Developmental Psychology, 22, I 15-123.

Webster-Stratton, C. (1985). Comparison of abusive and nonabusive families with conduct-disordered children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 55, 59-69.

Wolfe, D. A. ( 1991 ). Preventing physical and emotional abuse of children. New York: Guilford.

Wyatt, G. E., & Peters, S. D. (1986). Methodological considerations in research on the prevalence of child sexual

abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 10, 241-251.

Zucker, R. A., Noll, R. B., & Fitzgerald, H. E. (1986). Risk and coping in children of alcoholics. NIAAA grant A A 07065, Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI.

R6sum6---Dans cette 6tude, les auteurs ont examin6 deux modbles qui expliqueraient comment les punitions corporelles

sont transmises d'une g6n6ration a l'autre. Le module qui s'appuye sur la thdorie de I'apprentissage social indique

que les punitions corporelles influencent le comportement agressif chez I'enfant. Par contre, la th6orie du temp6rament

comme facteur explicatif sugg~re que le comportement agressif de I'enfant influence les parents b. avoir recours aux

punitions corporelles. L'6tude a engag6 la participation de 1.536 parents et 983 coll6giens et coll6giennes. On a 6tudi6

la question des punitions corporelles tant du point de vue du pbre que de la m~re et de l'enfant. Selon I'analyse, le

module de l'apprentissage social est celui qui s'avere le plus coh6rent avec les donn6es.

R e s u m e n - - E s t e estudio familiar examin6 dos modelos en cuanto a la transmisi6n intergeneracional del maltrato

corporal. El modelo hasado en fundamentos del aprendizaje social afirmo que el castigo corporal influye en la conducta

agresiva del nifio/a. El modelo basado en la teoria del temperamento sugiri6 que la conducta agresiva del nifio/a

influye en el uso parental del castigo fisico. Participaron 1,536 padres de 983 estudiantes universitarios. Se evalu6 el

castigo corporal desde la perspectiva del padre, la madre y el nifio/a. Los amilisis revelaron que el modelo de

aprendizaje social era m~is consistente con los datos.

También podría gustarte

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2104)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Film-Literature Encounters MA FilmLit Core ModuleDocumento9 páginasFilm-Literature Encounters MA FilmLit Core ModuleAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Theories of Moral Development PDFDocumento22 páginasTheories of Moral Development PDFZul4Aún no hay calificaciones

- 2019 Audit-1 Course OutlineDocumento5 páginas2019 Audit-1 Course OutlineGeraldo MejillanoAún no hay calificaciones

- Pronunciation PairsDocumento2 páginasPronunciation PairsFerreira Angello0% (1)

- HillErroll Caribbean Theatre 1991Documento7 páginasHillErroll Caribbean Theatre 1991Andrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- S - Team: Daily Lesson LogDocumento4 páginasS - Team: Daily Lesson LogJT SaguinAún no hay calificaciones

- Final Essay Teaching Indigenous Australian StudentsDocumento3 páginasFinal Essay Teaching Indigenous Australian Studentsapi-479497706Aún no hay calificaciones

- Nutrition ReflectionsDocumento13 páginasNutrition Reflectionsapi-252471038Aún no hay calificaciones

- THTR 1009 2177 Crowe Kevin Syllabus Not UpdatedDocumento6 páginasTHTR 1009 2177 Crowe Kevin Syllabus Not UpdatedAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Matthew ArnoldDocumento31 páginasMatthew ArnoldAndrew Kendall100% (1)

- Quick Start Guide Par.3Documento12 páginasQuick Start Guide Par.3Andrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- AC+ For CA (iOS) v1.0 - English FrenchDocumento16 páginasAC+ For CA (iOS) v1.0 - English FrenchAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Trauma History and Memory in Farming of The BonesDocumento19 páginasTrauma History and Memory in Farming of The BonesAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Lecture14 DefenseDocumento8 páginasLecture14 DefenseAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Brooke - Stanley@stockton - Edu: Course Syllabus LITT 2306: Cultures of ColonialismDocumento11 páginasBrooke - Stanley@stockton - Edu: Course Syllabus LITT 2306: Cultures of ColonialismAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Literary Criticism: Course DescriptionDocumento2 páginasLiterary Criticism: Course DescriptionAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Project Muse 205457Documento30 páginasProject Muse 205457Andrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- The Specter of InterdisciplinarityDocumento21 páginasThe Specter of InterdisciplinarityAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Well, I'm Dashed! Jitta, Pygmalion, and Shaw's RevengeDocumento28 páginasWell, I'm Dashed! Jitta, Pygmalion, and Shaw's RevengeAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Miss Julie: NOTES: Setting The StageDocumento15 páginasMiss Julie: NOTES: Setting The StageAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Assignment-1 Noc18 hs31 15Documento3 páginasAssignment-1 Noc18 hs31 15Andrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- A Short Introduction To Literary Criticism: Saeed Farzaneh FardDocumento10 páginasA Short Introduction To Literary Criticism: Saeed Farzaneh FardAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Textual Pleasures and Violent Memories in Edwidge Danticat Farming of The BonesDocumento19 páginasTextual Pleasures and Violent Memories in Edwidge Danticat Farming of The BonesAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Terror and Violence in Who's Afraid of Virginia WoolfDocumento10 páginasTerror and Violence in Who's Afraid of Virginia WoolfAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Handout On TragedyDocumento3 páginasHandout On TragedyAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Sample Essay Truth and Illusion, PantomimeDocumento9 páginasSample Essay Truth and Illusion, PantomimeAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- A Golden Age Final EssayDocumento6 páginasA Golden Age Final EssayAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Character FoilsDocumento2 páginasCharacter FoilsAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- Ba Performing ArtsDocumento14 páginasBa Performing ArtsAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- 98 217 1 PB PDFDocumento7 páginas98 217 1 PB PDFAndrew KendallAún no hay calificaciones

- MAT 135: Final Project Guidelines and Grading GuideDocumento6 páginasMAT 135: Final Project Guidelines and Grading GuideKat MarshallAún no hay calificaciones

- Truancy Is The Most Common Problems Schools Face As StudentsDocumento2 páginasTruancy Is The Most Common Problems Schools Face As StudentsTiffany BurnsAún no hay calificaciones

- Department of Education: Quarter Identified Issues Action Taken/ RemarksDocumento1 páginaDepartment of Education: Quarter Identified Issues Action Taken/ Remarksai lyn100% (1)

- Clarke Book Review - Thinking Through Project-Based Learning - Guiding Deeper Inquiry Krauss, Jane and Boss, Suzie (2013) .Documento4 páginasClarke Book Review - Thinking Through Project-Based Learning - Guiding Deeper Inquiry Krauss, Jane and Boss, Suzie (2013) .danielclarke02100% (1)

- Curriculum Vitae: Sunil KumarDocumento2 páginasCurriculum Vitae: Sunil KumarDeepak NayanAún no hay calificaciones

- Lesson Plans - Catholic Schools' Week - Jan 29-Feb 3Documento2 páginasLesson Plans - Catholic Schools' Week - Jan 29-Feb 3Christi TorralbaAún no hay calificaciones

- Adtw722 eDocumento2 páginasAdtw722 ePaapu ChellamAún no hay calificaciones

- The Relationship Between Writing Anxiety and Students' Writing Performance at Wolkite University First Year English Major StudentsDocumento14 páginasThe Relationship Between Writing Anxiety and Students' Writing Performance at Wolkite University First Year English Major StudentsIJELS Research JournalAún no hay calificaciones

- Ghaf TreeDocumento2 páginasGhaf Treeapi-295499140Aún no hay calificaciones

- Eled 3223 - Lesson PlanDocumento4 páginasEled 3223 - Lesson Planapi-282515154Aún no hay calificaciones

- Nursing AuditDocumento28 páginasNursing Auditmarsha100% (1)

- 0620 s14 QP 61Documento12 páginas0620 s14 QP 61Michael HudsonAún no hay calificaciones

- Syllabus:: Course Information SheetDocumento4 páginasSyllabus:: Course Information SheetManoj SelvamAún no hay calificaciones

- Jean PiagetDocumento7 páginasJean Piagetsanjay_vany100% (1)

- Clinical Performance Assessments - PetrusaDocumento37 páginasClinical Performance Assessments - Petrusaapi-3764755100% (1)

- TIMSS and PISADocumento15 páginasTIMSS and PISASuher Sulaiman100% (1)

- Howard GardnerDocumento51 páginasHoward Gardnersyaaban69Aún no hay calificaciones

- Pub Rel 001 10139 Long StacyDocumento4 páginasPub Rel 001 10139 Long StacyDR-Nizar DwaikatAún no hay calificaciones

- Exemplar For Internal Achievement Standard Physical Education Level 1Documento13 páginasExemplar For Internal Achievement Standard Physical Education Level 1api-310289772Aún no hay calificaciones

- Mind The Gap: Co-Created Learning Spaces in Higher EducationDocumento15 páginasMind The Gap: Co-Created Learning Spaces in Higher Educationvpvn2008Aún no hay calificaciones

- Work EducationDocumento156 páginasWork EducationSachin BhaleraoAún no hay calificaciones

- Collaborative LearningDocumento11 páginasCollaborative LearningChristopher PontejoAún no hay calificaciones

- Dep Ed 4Documento26 páginasDep Ed 4dahlia marquezAún no hay calificaciones