Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Judge Throws Out Cinemark Lawsuit

Cargado por

9newsTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Judge Throws Out Cinemark Lawsuit

Cargado por

9newsCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Case 1:12-cv-02514-RBJ-MEH Document 337 Filed 06/24/16 USDC Colorado Page 1 of 8

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO

Judge R. Brooke Jackson

Civil Action No. 12-cv-02517-RBJ-MEH

JOSHUA R. NOWLAN,

Plaintiff,

v.

CINEMARK HOLDINGS, INC.,

CINEMARK USA, INC., and

CENTURY THEATERS, INC.,

Defendants.

________________________

Civil Action No. 12-cv-02687-RBJ-MEH

DION ROSBOROUGH,

TONY BRISCOE,

JON BOIK, next friend of Alexander Boik,

EVAN FARIS,

RICHELE HILL, and

DAVID WILLIAMS,

Plaintiffs,

v.

CINEMARK HOLDINGS, INC.,

CINEMARK USA, INC., and

CENTURY THEATERS, INC.,

Defendants.

________________________

Civil Action No. 13-cv-00046-RBJ-MEH

MUNIRIH F. GRAVELLY,

Plaintiff,

v.

CINEMARK HOLDINGS, INC.,

CINEMARK USA, INC., and

CENTURY THEATERS, INC.,

Defendants.

________________________

Civil Action No. 13-cv-01995-RBJ-MEH

ASHLEY MOSER,

Plaintiff,

v.

CINEMARK HOLDINGS, INC.,

CINEMARK USA, INC., and

CENTURY THEATERS, INC.,

1

Case 1:12-cv-02514-RBJ-MEH Document 337 Filed 06/24/16 USDC Colorado Page 2 of 8

Defendants.

________________________

Civil Action No. 13-cv-02988-RBJ-MEH

NICK GALLUP,

Plaintiff,

v.

CINEMARK HOLDINGS, INC.,

CINEMARK USA, INC., and

CENTURY THEATERS, INC.,

Defendants.

________________________

Civil Action No. 13-cv-03316-RBJ-MEH

STEFAN MOTON,

Plaintiff,

v.

CINEMARK HOLDINGS, INC.,

CINEMARK USA, INC., and

CENTURY THEATERS, INC.,

Defendants.

________________________

Civil Action No. 14-cv-01923-RBJ-MEH

CHANTEL L. BLUNK,

MAXIMUS T. BLUNK, and

HAILEY M. BLUNK,

Plaintiffs,

v.

CINEMARK HOLDINGS, INC.,

CINEMARK USA, INC., and

CENTURY THEATERS, INC.,

Defendants.

________________________

Civil Action No. 14-cv-01976-RBJ-MEH

JAMISON TOEWS

Plaintiff,

v.

CINEMARK HOLDINGS, INC.,

CINEMARK USA, INC., and

CENTURY THEATERS, INC.,

Defendants.

Case 1:12-cv-02514-RBJ-MEH Document 337 Filed 06/24/16 USDC Colorado Page 3 of 8

ORDER

These cases 1 are before the Court on a motion for summary judgment [ECF No. 321]

filed by defendants Cinemark Holdings, Cinemark USA, and Century Theaters. The Court

exercises jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1332. For the following reasons, the motion is

granted.

BACKGROUND

This is the third dispositive motion the Court has considered in this case. The previous

two orders thoroughly outlined the factual background. See ECF Nos. 49, 245. The Court

incorporates the facts by reference and does not repeat the details here. This case arises from the

horribly tragic mass shooting at the Century Aurora 16 theater complex in Aurora, Colorado on

July 20, 2012 where James Holmes killed 12 individuals and wounded many others. The

plaintiffs are individuals who were injured and survivors of those who were killed. Defendants

Cinemark, USA and Century Theatres, Inc. are wholly owned subsidiaries of defendant

Cinemark Holdings, Inc., and the Court refers to them collectively as Cinemark or

defendants.

The Colorado Premises Liability Act governs plaintiffs claim. This statute establishes

the possible liability of a landowner when someone is injured on his property by reason of the

condition of such property, or activities conducted or circumstances existing on the property.

C.R.S. 1321115(2). A movie-theater patron is considered an invitee who may recover for

damages caused by the landowners unreasonable failure to exercise reasonable care to protect

1

The cases have been consolidated such that all filings can be found in the docket for the lowest

numbered case: 12-cv-02514-RBJ-MEH. The plaintiffs in that earliest-filed case are no longer parties to

this matter. However, all references to docket numbers are references to 12-cv-02514-RBJ-MEH.

3

Case 1:12-cv-02514-RBJ-MEH Document 337 Filed 06/24/16 USDC Colorado Page 4 of 8

against dangers of which he actually knew or should have known. C.R.S. 1321115(3)(c)(I)

(emphasis added).

Early on in this case, on October 18, 2012, defendants filed a motion to dismiss.

Cinemark argued that plaintiffs complaints failed to state a claim on which relief could be

granted. ECF No. 15. On April 17, 2013 the Court denied that motion. When considering a

motion to dismiss, the Court is required to accept plaintiffs allegations of fact as true and

construe inferences in their favor. Having done so, I agreed with United States Magistrate Judge

Hegartys recommendation and determined that plaintiffs had stated a claim. ECF No. 49.

After the parties had engaged in pre-trial discovery defendants filed their first motion for

summary judgment on November 1, 2013. ECF No. 108. Defendants argued that Cinemark

neither knew nor should have known of the danger of a mass shooting because the danger was

unforeseeable as a matter of law. Id. at 2. On August 15, 2014 the Court denied the motion.

ECF No. 245. The Courts order focused narrowly on whether a jury should decide if defendants

knew or should have known of the danger on the premises. The Court expressly noted that it

was in no way holding as a matter of law that Cinemark should have known of the danger of

someone entering one of its theaters through the back door and randomly shooting innocent

patrons. Id. at 16. The Court held only that plaintiffs had presented enough evidence to create

a genuine dispute of fact as to whether defendants knew or should have known of security risks,

rendering the knowledge element of the claim a jury issue. Id. at 1617. The Court reserved all

other issues. Id. at 17.

Defendants now move for summary judgment on the element of causation. ECF No. 321

at 2. The pending motion poses the ultimate question of whether the Court should dismiss the

case as a matter of law or whether the finder of fact should decide the issue of causation.

Case 1:12-cv-02514-RBJ-MEH Document 337 Filed 06/24/16 USDC Colorado Page 5 of 8

SUMMARY JUDGMENT STANDARD

The purpose of a trial, whether by the court or a jury, is to resolve disputed issues of fact.

Summary judgment simply means that the Court can decide the case, for either party, if there is

no genuine dispute of fact that needs to be resolved at a trial. Summary judgment is appropriate

if the pleadings, the discovery and disclosure materials on file, and any affidavits show that

there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the movant is entitled to judgment as a

matter of law. Utah Lighthouse Ministry v. Found. for Apologetic Info. & Research, 527 F.3d

1045, 1050 (10th Cir. 2008) (quoting Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(c)).

When deciding a motion for summary judgment, the Court considers the factual record,

together with all reasonable inferences derived therefrom, in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party . . . . Id. The moving party has the burden of producing evidence showing the

absence of a genuine issue of material fact. Celotex Corp. v. Catrett, 477 U.S. 317, 325 (1986).

In challenging such a showing, the non-movant must do more than simply show that there is

some metaphysical doubt as to the material facts. Matsushita Elec. Indus. Co. v. Zenith Radio

Corp., 475 U.S. 574, 586 (1986). Only disputes over facts that might affect the outcome of the

suit under the governing law will properly preclude the entry of summary judgment. Anderson

v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 248 (1986). A dispute about a material fact is genuine if

the evidence is such that a reasonable jury could return a verdict for the nonmoving party. Id.

Case 1:12-cv-02514-RBJ-MEH Document 337 Filed 06/24/16 USDC Colorado Page 6 of 8

ANALYSIS

In Colorado, in order to prevail on a negligence theory the plaintiff must prove that the

defendants tortious actions were a proximate cause of the plaintiffs injury. City of Aurora v.

Loveless, 639 P.2d 1061, 1063 (Colo. 1981) (internal citations omitted). The duty of a

landowner under the Colorado Premises Liability Act to exercise reasonable care to protect

invitees against dangers of which he actually knew or should have known similarly requires

proof of proximate cause. Proximate cause is often understood as the legal cause of an injury.

See Moore v. Western Forge Corp., 192 P.3d 427, 436 (Colo. App. 2007).

As part of the proximate cause inquiry, plaintiffs must prove that the alleged tortious

conduct constitutes a substantial factor in producing the injury. See North Colo. Medical Ctr.

v. Comm. on Anticompetitive Conduct, 914 P.2d 902, 908 (Colo. 1996) (Colorados proximate

cause [law] is intended to ensure that casual and unsubstantial causes do not become

actionable.). One factor may have such a predominant effect in causing the [harm] as to

make the effect of [another factor] insignificant and, therefore, to prevent it from being a

substantial factor. Smith v. State Compensation Ins. Fund, 749 P.2d 462, 464 (Colo. App.

1987). While proximate cause is typically a question of fact reserved to the jury, the Court may

conclude, as a matter of law, that such a predominant cause exists, and that there can be no other

substantial factors.

Two of my colleagues have addressed the issue of proximate cause in mass-shooting

cases where the defendant is an entity rather than the shooter. In two separate cases involving

the Columbine High School shootings, Judge Babcock considered whether there could be

another substantial factor in causing plaintiffs injuries beyond the actions of the two

assailantsEric Harris and Dylan Klebold. First, in Castaldo v. Stone, plaintiffs sued the

Case 1:12-cv-02514-RBJ-MEH Document 337 Filed 06/24/16 USDC Colorado Page 7 of 8

Jefferson County School District, the Jefferson County Sheriffs Department, and various

individuals associated with those entities. 92 F.Supp.2d 1124, 1133 (D. Colo. 2001). The court

held that Harris and Klebolds actions on April 20, 1999 were the predominant, if not sole,

cause of Plaintiffs injuries. Id. at 1171. Later, in Ireland v. Jefferson County Sheriffs

Department, the court dismissed plaintiffs negligence claim against the organizer of a gun show

at which Harris and Klebold purchased a shotgun. 193 F.Supp.2d 1201, 123132 (D. Colo.

2002). Mirroring the analysis in Castaldo, the court reasoned that [e]ven if [the gun show

organizers] actions contributed in some way to Plaintiffs injuries, the shooters actions were

the predominant, if not sole cause of the injuries. Id. at 1232.

More recently, in Phillips v. Lucky Gunner, LLC, Judge Matsch addressed this issue in

the context of the Holmes shootings. 84 F.Supp.3d 1216, 1228 (D. Colo. 2015). Plaintiffs sued

various gun shops where Holmes had purchased ammunition and other equipment that he used in

the mass shooting. Id. Plaintiffs daughter died in the attack, and plaintiffs alleged, among other

claims, that the gun-shop entities were liable on negligence grounds. Id. Judge Matsch

dismissed the negligence claim, holding that, even if he were to find that defendants owed a duty

of care, defendants sales of ammunition and other items to Holmes did not proximately cause

the plaintiffs daughters death. Id. The court reasoned:

There can be no question that Holmess deliberate, premeditated criminal acts

were the predominant cause of plaintiffs daughters death. Holmes meticulously

prepared for his crime, arriving at the theater equipped with multiple firearms,

ammunition, and other gear allegedly purchased from several distinct business

entities operating both online and through brick and mortar locations. Neither the

web nor the face-to-face sales of ammunition and other products to Holmes can

plausibly constitute a substantial factor causing the deaths and injuries in this

theater shooting.

Id.

Case 1:12-cv-02514-RBJ-MEH Document 337 Filed 06/24/16 USDC Colorado Page 8 of 8

I agree with my colleagues analysis of the proximate cause issue. Here, plaintiffs claim

that defendants failed to provide certain safety measures such as placing an alarm on the exit

door or employing security officers on the evening in question. Even if such omissions

contributed in some way to the injuries and deaths, the Court finds that Holmes premeditated

and intentional actions were the predominant cause of plaintiffs losses. See North Colo.

Medical Ctr., 914 P.2d at 908 (if a combination of reasons could have produced the harm, but

one such reason demonstrates prominence, then only the predominant cause can constitute a

substantial factor satisfying the proximate cause standard). The Court concludes that a

reasonable jury could not plausibly find that Cinemarks actions or inactions were a substantial

factor in causing this tragedy. Therefore, as a matter of law, defendants conduct was not a

proximate cause of plaintiffs injuries.

ORDER

For the reasons described above, the motion for summary judgment, ECF No. 321, is

GRANTED. These consolidated civil actions are hereby dismissed with prejudice.

DATED this 24th day of June, 2016.

BY THE COURT:

___________________________________

R. Brooke Jackson

United States District Judge

También podría gustarte

- Mental Health Transitional Living (MHTL) Homes Frequently Asked QuestionsDocumento5 páginasMental Health Transitional Living (MHTL) Homes Frequently Asked Questions9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- Knock-Off Seat WarningDocumento2 páginasKnock-Off Seat Warning9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- 2023annualreport CobDocumento38 páginas2023annualreport Cob9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- Case 1 CPO 2022 6373 CDHS Response Washington December 7 2023 FINALDocumento10 páginasCase 1 CPO 2022 6373 CDHS Response Washington December 7 2023 FINAL9news100% (1)

- 23SA300Documento213 páginas23SA300Brandon Conradis100% (5)

- EEOC Charge With SignaturesDocumento35 páginasEEOC Charge With Signatures9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- In The Supreme Court of The United States: Petition For Writ of CertiorariDocumento43 páginasIn The Supreme Court of The United States: Petition For Writ of CertiorariAaron ParnasAún no hay calificaciones

- Complaint Filed in Colorado Supreme Court Regarding Misconduct by Chaffee County DA Linda StanleyDocumento20 páginasComplaint Filed in Colorado Supreme Court Regarding Misconduct by Chaffee County DA Linda Stanley9news100% (1)

- Nuggets Parade Route InvoiceDocumento1 páginaNuggets Parade Route Invoice9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- Colorado Medical Board - Non-Disciplinary Interim Practice Agreement For Geoffrey S. Kim, M.D.Documento4 páginasColorado Medical Board - Non-Disciplinary Interim Practice Agreement For Geoffrey S. Kim, M.D.9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- DPS Slavens LawsuitDocumento37 páginasDPS Slavens Lawsuit9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- Invoice For Portable Toilets - Nuggets ParadeDocumento1 páginaInvoice For Portable Toilets - Nuggets Parade9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- People Exhibits Prelim HearingDocumento92 páginasPeople Exhibits Prelim Hearing9news100% (1)

- Complaint Filed in Colorado Supreme Court Regarding Misconduct by Chaffee County DA Linda StanleyDocumento20 páginasComplaint Filed in Colorado Supreme Court Regarding Misconduct by Chaffee County DA Linda Stanley9news100% (1)

- Executive Summary and Recommendations HB 22-1327 9.1.23Documento16 páginasExecutive Summary and Recommendations HB 22-1327 9.1.239news0% (1)

- Order Denying Defendant's Motion To StayDocumento14 páginasOrder Denying Defendant's Motion To Stay9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- Washington County Child Welfare ConcernsDocumento10 páginasWashington County Child Welfare Concerns9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- CDOC Offender Assignment and Pay 2023Documento19 páginasCDOC Offender Assignment and Pay 20239newsAún no hay calificaciones

- Wet Mountain Tribune Federal LawsuitDocumento10 páginasWet Mountain Tribune Federal Lawsuit9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- Union Letter To Aurora Mayor Mike CoffmanDocumento1 páginaUnion Letter To Aurora Mayor Mike Coffman9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- Lakewood Police Statement On The Death of Robert RiggDocumento1 páginaLakewood Police Statement On The Death of Robert Rigg9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- 2022-06-22 Mayor Hancock Letter To Commissioner Teal Re Daniels ParkDocumento1 página2022-06-22 Mayor Hancock Letter To Commissioner Teal Re Daniels Park9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- Ruby Johnson v. Detective Gary Staab - Complaint For Damages - 12-01-2022Documento15 páginasRuby Johnson v. Detective Gary Staab - Complaint For Damages - 12-01-20229newsAún no hay calificaciones

- Order Denying Defendant's Motion To StayDocumento14 páginasOrder Denying Defendant's Motion To Stay9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- 76 - Amended ComplaintDocumento46 páginas76 - Amended Complaint9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- Adams & Broomfield Counties Office of The Coroner ResponseDocumento5 páginasAdams & Broomfield Counties Office of The Coroner Response9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- Redacted - 5380 Worchester ST Warrant AffidavitDocumento6 páginasRedacted - 5380 Worchester ST Warrant Affidavit9newsAún no hay calificaciones

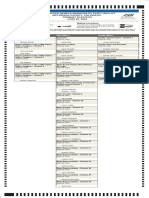

- Democratic State Sample Primary BallotDocumento1 páginaDemocratic State Sample Primary Ballot9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- Element PPP Forgiveness App RedactedDocumento14 páginasElement PPP Forgiveness App Redacted9newsAún no hay calificaciones

- PUC HSD Decision March 2022Documento22 páginasPUC HSD Decision March 20229newsAún no hay calificaciones

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (119)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2099)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- New Fence Ordinance - Detroit LakesDocumento8 páginasNew Fence Ordinance - Detroit LakesMichael AchterlingAún no hay calificaciones

- Constable Market Definition FactorsDocumento5 páginasConstable Market Definition Factorssyahidah_putri88Aún no hay calificaciones

- Salient Features - ROCDocumento78 páginasSalient Features - ROCRon NasupleAún no hay calificaciones

- Utulo V PasionDocumento1 páginaUtulo V PasionElaizza ConcepcionAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is A Writ of Mandamus?: Key TakeawaysDocumento7 páginasWhat Is A Writ of Mandamus?: Key Takeawaysleonalopez30Aún no hay calificaciones

- Abdulla v. PeopleDocumento1 páginaAbdulla v. PeopleMarc VirtucioAún no hay calificaciones

- People Vs PajaresDocumento4 páginasPeople Vs PajaresDanny DayanAún no hay calificaciones

- Sun Insurance Vs AsuncionDocumento14 páginasSun Insurance Vs Asuncion_tt_tt_Aún no hay calificaciones

- Transnational Organized CrimeDocumento5 páginasTransnational Organized CrimeSalvador Dagoon JrAún no hay calificaciones

- Revised Code of ConductDocumento58 páginasRevised Code of ConductMar DevelosAún no hay calificaciones

- Contributor Agreement Form - AMPSDocumento10 páginasContributor Agreement Form - AMPSEntorque RegAún no hay calificaciones

- Cyber LawDocumento7 páginasCyber LawPUTTU GURU PRASAD SENGUNTHA MUDALIAR100% (4)

- Vivian B. Escoto's Reasons for PromotionDocumento23 páginasVivian B. Escoto's Reasons for PromotionVivian Escoto de Belen67% (3)

- CRPC ProjectDocumento23 páginasCRPC Projectbhargavi mishraAún no hay calificaciones

- Mark - Non Registrable Industrial DesignDocumento13 páginasMark - Non Registrable Industrial DesignHannah Keziah Dela CernaAún no hay calificaciones

- Canon 1-5 Legal Ethics DigestsDocumento26 páginasCanon 1-5 Legal Ethics DigestsCeedee RagayAún no hay calificaciones

- LABOR - Consolidated Case Digests 2012-2017Documento1699 páginasLABOR - Consolidated Case Digests 2012-2017dnel13100% (4)

- Textio v. OngigDocumento17 páginasTextio v. OngigNat LevyAún no hay calificaciones

- G.R. No. L-11002 Supreme Court Case on Omission of Taxable PropertyDocumento5 páginasG.R. No. L-11002 Supreme Court Case on Omission of Taxable PropertyCJ N PiAún no hay calificaciones

- Atty. Chico - Civil Law - Torts and DamagesDocumento56 páginasAtty. Chico - Civil Law - Torts and DamagesErick Paul de VeraAún no hay calificaciones

- Francisco-Vs - HouseDocumento4 páginasFrancisco-Vs - HouseRon AceAún no hay calificaciones

- (CLJ) Court TestimonyDocumento51 páginas(CLJ) Court TestimonyEino DuldulaoAún no hay calificaciones

- Professional Misconduct of Lawyers in IndiaDocumento9 páginasProfessional Misconduct of Lawyers in IndiaAshu 76Aún no hay calificaciones

- Competition LawDocumento15 páginasCompetition Lawminakshi tiwariAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Study of A BarangayDocumento5 páginasCase Study of A BarangayKourej Neyam Cordero100% (2)

- Moot 1 PDFDocumento15 páginasMoot 1 PDFVivek SinghAún no hay calificaciones

- Rule of EquityDocumento11 páginasRule of EquityNeha MakeoversAún no hay calificaciones

- TGA User ManualDocumento310 páginasTGA User Manualfco85100% (1)

- Hon. Geraldine R. Ortega: SP-014-Ø Re-Endorsement (RAB) No. 121-2020Documento46 páginasHon. Geraldine R. Ortega: SP-014-Ø Re-Endorsement (RAB) No. 121-2020Jane Tadina FloresAún no hay calificaciones

- Barbados road safety overviewDocumento1 páginaBarbados road safety overviewBarbi PoppéAún no hay calificaciones