Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Contours of Conversion: The Geography of Islamization in Syria 600-1500

Cargado por

AbbasTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Contours of Conversion: The Geography of Islamization in Syria 600-1500

Cargado por

AbbasCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Contours of Conversion:

The Geography of Islamization in Syria, 6001500

Thomas A. Carlson

Oklahoma State University

The Islamization of Syria, a multi-faceted social and cultural process not limited

to demography, was slow and highly variable across different locales. This article

analyzes geographical worksten in Arabic, one in Persian, and one in Hebrew

as well as the earliest Ottoman defters of the province to outline the process of

Islamization in Syria from the Islamic conquest in the seventh century to the Ottoman conquest in the sixteenth. Geographical texts cannot be mined as databases,

but when interpreted as literature they provide often detailed information regarding the foundation of mosques, the slow conversion of multi-religious shrines, and

areas within Syria known for particular religious affiliations.

introduction

When Khlid b. al-Wald invaded Syria in 13/634, the region was inhabited by a religiously

mixed population with multiple kinds of Christianity present alongside Judaism and paganism. When the Ottoman sultan Selim I conquered Mamluk Syria nine centuries later in

922/1516, the regions religious diversity looked distinctively more Muslim, with Sunnis of

four legal schools sharing the land with Druze, Nuayrs, Ismailis, and Twelver Shiites, in

addition to reduced populations of Christians and Jews. The process of Islamization whereby

regions such as Syria slowly shifted from areas without Muslims to those where Muslims

formed the majority is one of the more dramatic transformations of the medieval world.

Both the mechanisms and the contours of Syrias Islamization are poorly understood.

In part this is due to the absence of surviving demographic data before the Ottoman tax

census records of the sixteenth century. After Selim Is conquest, the bulk of Syria was

divided between provincial governments (sg. eyalet) based in Aleppo, Tripoli, and Damascus, although portions of eastern Syria around al-Raqqa were assigned to Ruh (modern

Urfa), while areas historically regarded as northern Syria were incorporated into the eyalet of

Dlqdir or the Ramanid principality.1 The tax registers (sg. defter) produced by the new

provincial governments, many of which survive, identify religious minorities due to the differential taxation applied to non-Muslims.2 These records demonstrate that in the sixteenth

century the Muslim population of Syria formed an overwhelming majority in the countryside

Earlier versions of this article were greatly improved by suggestions from Michael Cook, the late Patricia Crone,

Peter Brown, Christian Sahner, the Princeton Islamic Studies Colloquium, and the JAOS anonymous reviewers.The

author records his gratitude for their corrections and recommendations, while acknowledging that all remaining

errors are his own.

1. An account of the Ottoman conquest is found in Bakhit 1982b: 134.

2. Scholarship on the Ottoman defters remains uneven. The 1536 census records of Aleppo have been published

(ener and Dutolu 2010); I have not found any edition or analysis of defters from Tripoli. Analyses of the defters

from Damascus and Ajln, two of the nine districts (sg. sanjak) of the province of Damascus, have been published

in Bakhit 1982b; Bakhit and Hamud 1989 and 1991. Fifteen defters for four additional sanjaks of the province of

Damascus were analyzed in Cohen and Lewis 1978. Finally, Bakhit 1982a is a synthesis of the Christian portion of

the non-Muslim population of the province of Damascus as a whole.

Journal of the American Oriental Society 135.4 (2015)

791

792

Journal of the American Oriental Society 135.4 (2015)

and a large majority in most towns and cities.3 Much scholarly debate centers upon how

quickly the majority of the population adopted Islam.

But demographic change was only one component of a multi-faceted process of Islamization in Syria. Many medieval Muslim jurists seem to have regarded widespread conversion to

Islam as irrelevant to Islamic society, while increased enforcement of regulations upon nonMuslims to demonstrate the superiority of Islam appears more important to their notion of

Islamization. The Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik b. Marwn (r. 6586/685705) is generally

credited with replacing Byzantine coins with aniconic Islamic coins and with building the

Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, showing that state-sponsored Islamization had numismatic

and architectural implications. Governmental Islamization was only one component of the

broader, and far slower, process by which Syria became in some sense more Islamic. That

process transformed urban environments, as mosques replaced churches, synagogues, and

temples as the foci of cities.4 Islamization included the conversion of landscapes, as monasteries fell into ruin and Muslim shrines sprang up instead.5 Concepts of areas as primarily

one religion or another shifted with Islamization, as did social expectations regarding typical

relationships between members of different religious groups. Islamization was a complex and

multi-dimensional process that spanned many centuries.

This lengthier process was also not one-directional. Muslims converted to Christianity as well as vice versa. Ruined non-Muslim religious sites could sometimes be rebuilt.6

Al-Muqaddas (fl. late tenth century) acknowledged that despite his high praise for Syrias

many advantages, some [of its people] have apostasized.7 Yqt al-amaw (d. 626/1229)

mentioned a village named Imm between Aleppo and Antioch, in which today everyone is

Christian, but he quotes the Risla of Ibn Buln from the eleventh century to say that two

centuries earlier it had a mosque.8 In certain contexts Islam was not the only religion supported by the state, as Muslim rulers sometimes provided stipends to Jewish and Christian

religious authorities in addition to the ulema.9 Furthermore, the Byzantine reconquest and

the Crusades reintroduced non-Muslim rule to portions of Syria from 358/969 to 690/1291,

so that even state support for Islam could not be taken for granted. Indeed, under Frankish

rule a large enough number of Muslims sought to become Christian that canon law needed

3. Multiple tax registers were compiled at different times for different portions of Syria, making it impossible to

speak of proportions of the total population of the region at one time. Tapu defteri 401 for the district of Damascus

in ca. 950/1543 seems to indicate a population approximately 90% Muslim, 9% Christian, and 1% Jewish, based

on tables in Bakhit 1982b: 3789. The tax registers do not record total population, but rather households (khna)

and bachelors (mujarrad) for each religious group. Thus, proportions of the population are necessarily approximate,

depending on the unknown average number of people per household in each community. Most scholars use a figure

of about five people per household to estimate total population, but as long as the household size did not vary significantly across religious boundaries, the precise multiplier should not greatly affect calculations of the proportion

of a population that was non-Muslim.

4. The classic studies of urbanism in Islamic society are Kennedy 1985; Lapidus 1967. For a more complete

historiography to 1994, and a critique of Islamic city as a category, see Haneda and Miura 1994.

5. The lengthy process of the conversion of holy sites is discussed by Talmon-Heller 2007b: 18890.

6. The twelfth-century Andalusi traveler Ibn Jubayr (1981: 25354; 1952: 32324) reported the conversion of a

traveling companion in Syria to Christianity. A fifteenth-century Trkmen ruler of the qqyunl confederation is

credited with building a church in eastern Anatolia (Sanjian 1969: 205).

7. Al-Muqaddasi 1994: 139; 1906: 152.

8. Yaqut al-Hamawi 1990, 4: 177 (the date of 540/1145 for the Risla is incorrect, being about a century too

late).

9. For an example of Fimid financial support for Palestinian Jews in the late tenth century, see Gil 1992: 551. For

an example of Zang giving a pair of church bells to a Syrian Orthodox church in al-Ruh, see Chabot 1917, 2: 136.

Carlson: The Geography of Islamization in Syria, 6001500

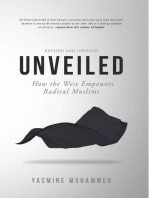

Fig.1. Cities, towns, and villages of medieval Syria.

793

794

Journal of the American Oriental Society 135.4 (2015)

to be developed in order to handle difficult social questions regarding marriage and slavery

in such cases.10 As Benjamin Kedar concludes, in the Frankish Levant, passages from Islam

to Christianity and vice versa were not rare at all.11

The boundaries of Syria in medieval Arabic geographical thought were different from

today. Yqt presented the most common definition of this region as extending from the

Euphrates to the town of al-Arsh on the Egyptian coastline southeast of Gaza, and from the

Arabian desert to the Mediterranean Sea (see map on previous page).12 This definition leaves

open how far into modern Turkey the region was thought to extend, and before the Byzantine reconquest of the tenth century the northwestern border of Syria was simply considered

to be the boundary of Byzantine control, sometimes even including Malaya on the upper

Euphrates as the northern edge of Syria.13 On the other hand, Yqt does not include any

major city north of Manbij and Aleppo, noting only in passing the border regions (thughr)

of al-Maa, arss, Adhana, and Marash.14 This article will take as the northern border

of Syria the Taurus Mountains of southeastern Anatolia, excluding Malaya but including the

border towns mentioned by Yqt.

The classic study of Islamization remains Richard Bulliets Conversion to Islam in the

Middle Period (1979). Bulliet analyzed biographical dictionaries to graph the adoption of

specifically Muslim names in several different regions across the Islamic world, making certain approximate assumptions about length of generations and age of conversion. He argued

that these distinctively Islamic names first appear within a lineage for a convert to Islam or

for his children, and graphing the incidence of Islamic names for the ulema in a biographical

dictionary gives a curve (p. 19) that can be taken as the conversion curve for the region as

a whole.15 The result is a summative S-curve that displays the Muslim proportion of the

population as monotonically increasing, whose slope represents the rate of conversion, first

slow, then increasing to a midpoint, and then decreasing to level off again as the number of

late adopters decrease. He suggests (pp. 109, 112) that conversions peaked from the lateeighth to the mid-tenth century, and that the rise of Shiite groups such as Druze, Nuayrs,

and Ismailis was occasioned by the late conversion of mountain Christians. Nevertheless, he

acknowledges (pp. 110, 112) that his proposed conversion curve is difficult to correlate with

the political, social, or religious history of Syria, and he concludes, Syria does not present

a tidy, easily understandable picture.

10. Kedar 1985: 326.

11. Kedar 1997a: 196.

12. Yaqut al-Hamawi 1990, 3: 355.

13. Ibn Hawqal 1964a: 154; 1964b, 1: 16465.

14. Yaqut al-Hamawi 1990, 3: 354.

15. Alwyn Harrison (2012: 38) suggested that Bulliets graphs are often misunderstood to refer to the total

population, when in fact they refer only to the percentages of those who would convertof the ultimate unquantifiable total of converts and therefore There is thus no way to extrapolate any quantifiable data regarding conversion,

or to identify the point at which Muslims became a numerical majority and the ahl al-dhimma a minority. This

interpretation picks up on certain nuances of Bulliets language, but Bulliet himself (1979: 1) seems to slip into

identifying the conversion curve with broader demographics, for example in his conclusion of a causal relationship

between the conversion of a majority of a regions population and the dissolution of central Islamic government in

that region (emphasis mine). It is also unclear how the stage in the conversion process to which Bulliet frequently

ascribes causal force would be comparable across countries if in one region it represented a large majority of the

population and in another conversion rates dwindled after the Muslim population reached around 20%. Michael

Morony (1990: 13637, 138) critiques Bulliets use of the conversion curve as a cause rather than a consequence,

but asserts that Bulliets curves represent the conversion of the population as a whole, albeit with some reservations.

Carlson: The Geography of Islamization in Syria, 6001500

795

Somewhat more recently, Nehemia Levtzion (1990: 290) summarized what is known

about the contours of the Islamization of Syria and Palestine before the Ottoman conquest,

based primarily on secondary scholarship with reference to primary sources by al-Baldhur

(d. 279/892) and Michael the Syrian (d. 1199). This account derives primarily from narrative historical sources, whether used by Levtzion or by the other scholars he cites, and

although narrative sources are helpful for connecting otherwise isolated data, their interests are typically circumscribed in ways that limit their utility for the purpose of describing

regional Islamization. Michael the Syrian, for example, is interested almost exclusively in

the secular rulers and in his own denomination of Christianity, and thus says very little

about other Christian groups such as the Chalcedonians, much less the Jewish population of

Syria. Al-Baldhurs Fut al-buldn primarily collects traditions about the seventh-century

conquests, and only mentions non-Muslims to the degree that they figure in such traditions,

without any attempt to discuss the state of non-Muslims in Syria in his own lifetime. Narrative sources need to be supplemented by additional evidence to provide a wider picture of

the Islamization of Syria.

Studies of Islamization in Syria since 1990 have focused on specific themes, restricted

source materials, and narrower time frames. Bethany Walker (2013) synthesized the archaeological evidence for Islamization into the ninth century at a site in central Jordan. Uri

Simonsohn (2013) examined legal sources from the early Islamic period to clarify the process of personal conversions, especially reversed and repeated conversions. Nancy Khaleks

Damascus after the Muslim Conquest (2011) focuses on the transformation of a capital city

to the end of the Umayyad dynasty, while Amikam Elad (1995) examined pilgrimage to

holy places in Jerusalem, primarily but not exclusively in the first couple of centuries of

Islam. R. Stephen Humphreys (2010a) argued that Christianity continued to prosper under

the Umayyad dynasty, bringing together a range of literary, economic, and archaeological

sources. For a later period, the conversion of Syrias religious topography was analyzed

by Daniella Talmon-Heller (2007a) for the eleventh to thirteenth centuries, indicating that

Islamization was not merely an early Islamic phenomenon. These studies, each important for

its scope, do not provide or permit the synthesis of a trajectory of Islamization, especially

after the Umayyad period ending in 132/750.

One body of evidence that allows us to provide a first sketch of the contours of the Islamization in Syria over the longue dure, from the conquests of the seventh century to the

Ottoman annexation of Syria in the sixteenth century, consists of the geographical texts composed by administrators, travelers, and belles-lettrists describing the region of Syria in the

medieval period. An eclectic body of Islamic geographical literature, primarily in Arabic but

partly in Persian, preserves indications of the progress of Islamization at different periods.

The complexity of this literature requires methodological nuance to interpret it, but properly

understood it is a valuable body of evidence for the development of Syrian society.

This article analyzes ten Arabic geographical works, as well as one work in Persian and

one in Hebrew. On the basis of these works it sketches a trajectory of Islamization in Syria

until the Ottoman conquest. The Islamic conquest of Syria began the process of Islamization

with the rapid installation of mosques and garrisons in the major cities and along the coastline, while the first inhabitants of Syria to adopt Islam were many of the Arabs who already

lived in the region before the seventh century. By contrast, there is little evidence for rural

Islamization before the tenth century, and the evidence that exists suggests that before this

period rural Islam in Syria was primarily a nomads religion. The Byzantine conquests of the

tenth to eleventh centuries and the subsequent Crusades reintroduced Christian rule in Syria,

which resulted in certain segments of this region being known for Christian populations more

796

Journal of the American Oriental Society 135.4 (2015)

than others, such as the area north of the Gha around Damascus and the coastline. Rule by

Christians and the confiscation of certain urban mosques may also have lent urgency to the

process of founding Muslim rural shrines, although in many cases the earliest shrines that

are known to have interested Muslims were dedicated to pre-Muslim figures, and in some

cases were maintained by Jews or Christians. When the Mamluks from Cairo expelled the

last Crusaders, they also devastated the coastline, leaving Christianity primarily attested in

northern Syria.16 Even under Mamluk rule, however, certain villages located along major

roads north of Damascus which were still entirely or predominantly Christian would have

reminded Muslim travelers that Syria was not an exclusively Muslim territory.

arabic geographical literature

The geographical literature that describes Syria under Muslim rule is an important body

of sources for the long process of Islamization.17 This literature does not form a single genre,

but rather exists in several forms. Al-Baldhurs Fut al-buldn is primarily a work of

history and traditions that describes places only by virtue of their having been conquered

by the Muslims. The geographers of the Balkh school, such as Ibn awqal (d. ca. 362/973)

and al-Muqaddas, divided their works by regions, each provided with a map. By far the

most extensive geographical work is the Mujam al-buldn of Yqt al-amaw, arranged

as a dictionary with place names in alphabetical order. The works of Benjamin of Tudela (d.

1173), Ibn Jubayr (d. 614/1217), and Ibn Baa (d. 770s/1370s) are travelogues intended

to convey geographical information. Nevertheless, the authors in the geographical discourse

utilized earlier works in different genres and freely quoted other authors, as is typical for

medieval Islamic scholarship.

Methodological Challenges

The evidence provided by the geographical literature is complicated by several factors.

Geographical works pay selective attention to certain non-Muslim groups more than others,

and therefore cannot be used to infer relative demographic strength. Thus al-Baldhurs

Fut al-buldn only mentions Syrian Jews briefly with respect to Damascus, Tripoli, im,

and Qaysriyya,18 but even after the massacre ordered by the Byzantine emperor Heraclius

in 629, Tiberias was an important center of the Jewish population.19 The greater interest in

Christians than in Jews, in al-Baldhur and later Muslim geographers, is probably due to

political opposition with the Christian empire of Constantinople rather than to demographic

realities. On the other hand, the Samaritan population of Filasn is singled out for attention

by al-Baldhur and later geographers, which likely reflects their presence exclusively in this

region.20 No indication of the relative strength between Jews, Samaritans, and Christians can

be inferred from these references.

Other features of literary texts also complicate the use of geographical works. Geographical literature often lists places, but lists of villages are necessarily not comprehensive, nor

can these lists be presumed to be representative. Furthermore, different authors have diverse

interests that influence the selection criteria, so unless the author has a clear interest in

16. The adverb is necessary: Arabic geographical texts do not devote much space to Mount Lebanon, which

continued to have a substantial Maronite Christian population to the present; see Levtzion 1990: 3067.

17. For a recent study of the literary aspects of this discourse of place, see Antrim 2012.

18. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 170, 174, 183, 187, 192; 1916: 19091, 195, 206, 211, 217.

19. Gil 1992: 810, 7071.

20. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 21517; 1916: 24445.

Carlson: The Geography of Islamization in Syria, 6001500

797

recording religion, the absence of a reference to a particular religious community or expected

religious edifice does not indicate its absence from the location. For example, while Ibn

Baa frequently mentions mosques in his descriptions of the places he visited, no matter

how briefly, Yqt only infrequently refers to mosques in his geographical dictionary. The

late ninth-century historian and geographer al-Yaqb (1918: 8687) does not mention any

mosque in Syria other than the Umayyad mosque of Damascus, being primarily interested

in recording the tribal affiliations of the various Arab populations. By contrast, Benjamin of

Tudela (1907) is principally interested in recording the distance between cities and the size

of the Jewish populations that lived there. Finally, as with most fields of medieval scholarship, information included in the geographical work may have been borrowed from an earlier

source without attribution, which makes it challenging to identify the period to which any

given assertion may pertain.21 The result is that these works cannot simply be transformed

into a database on which statistical analysis can be performed; rather, each text must be read

as a literary and linguistic performance, yet one intended to communicate certain facts about

the world.22

In a way, some of these challenges turn out to be surprising opportunities for writing the

history of Islamization. Literary geographical texts sometimes indicate whether the authors

regarded certain details as surprising or typical, which partially compensates for the lack of

comprehensive or representative data. Even the adoption of earlier texts words without modification or attribution, although bearing a different relationship to the authors experience

than new composition, typically reveals what the author regards as well said and plausible

enough. Such literary phenomena provide hints to the evolving expectations and assumptions regarding the religious landscape of Syria, which are as much a part of the process of

Islamization as progressive personal conversions or architectural repurposing; yet such attitudes and conceptions would be largely absent from census records. With a nuanced literary

approach, geographical texts can be useful sources for a full-orbed account of Islamization.

the earliest stage: rural arabs and major cities

The earliest stage of Islamization of Syria reported by the geographical texts is the conversion of nomadic Arabs, resulting in a distinction between often nomadic Muslims and

primarily sedentary non-Muslims. The core of the first Muslim community in Syria was

formed by the conquering Arab armies. Al-Baldhur reported that the Muslim commanders appealed to the largely Christian Arabs who already lived in Syria on the basis of their

common ancestry, with mixed results. Jabala, the chief of the Ban Ghassn, rejected Islam

(although one account says he converted and then apostasized) and moved to territory still

under Byzantine control, while the Arabs near Qinnasrn and Aleppo proved more agreeable,

with many of them accepting Islam.23 The degree to which the Islam of the conquest period

was viewed as an Arab society is perhaps indicated by the account of the Ban Taghlib

in the region of Diyr Raba to the northeastthe tribe remained Christian, but instead of

21. Antrim (2012: 72) indicates that some geographers use sources without acknowledgment after having specifically criticized them elsewhere.

22. The performative aspect of geographical literature is cogently stated by Antrim 2012: 3. Antrim critiques

Miquel 1967 for neglecting this literary dimension and simply mining the sources for information. Guy Le Strange

(1890) had earlier synthesized the geographical literature with regard to Syria, but in dicing up the sources, he

rendered it impossible to engage with the texts as literature. In the latter trait, however, he merely follows in the

footsteps of Yqt al-amaw.

23. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 18586, 198; 1916: 209, 224.

798

Journal of the American Oriental Society 135.4 (2015)

paying jizya it paid double the normal Muslim adaqa.24 Al-Baldhur presented the ruler as

saying, Since it is not the tax of the unbelievers (alj), we shall pay it and retain our faith.25

The chief of the Ban Ghassn is said to have made a similar offer to pay adaqa instead of

jizya, but in his case it was rejected.26 Syrian Arabs who had accepted Islam were already

sufficiently numerous for the military commander Ab Ubayda to station a garrison of them

in the city of Blis on the Euphrates within three years of the battle of Yarmk.27 It is unclear

how quickly the nomadic and semi-sedentary Arabs of Syria converted to the new religion,

but the swifter adoption of Islam by Arabs than by non-Arabs likely caused the religious

boundaries between Muslims and non-Muslims in the countryside to approximate the divide

between nomads and sedentary farmers.28

The Islamization of the sedentary population seems to have begun in major cities and

coastal towns, due to the presence of Muslim governors and garrisons.29 As presented by the

geographers of subsequent centuries, the circumstances of many cities surrender or conquest

provided a location to be used for the mosque, whether part of the citys cathedral or a new

site.30 A quarter of the main church of im was made into a mosque,31 while the cathedral

of St. John the Baptist in Damascus had a portion set aside for Muslim prayers.32 Aleppos

mosque was a new construction,33 as was that of Latakia on the coast.34 The link between

coastal garrisons and mosques is made explicit by an account reported by al-Baldhur that

the caliph Uthmn directed his cousin Muwiya, then governor of Syria, to garrison the

coastal towns, to build new mosques, and to enlarge existing mosques.35 Thus, al-Baldhur

referred to mosques in the cities of Asqaln in the days of Ibn al-Zubayr (d. 73/692), the

newly founded district capital al-Ramla by 101/720, al-Maa by 84/703, and arss by

172/788.36 He also indicated that Muwiya transferred Muslim populations to the coastal

cities of Tyre, Acre, and Antioch.37 Later geographers mentioned Jerusalems Dome of

the Rock, built by the caliph Abd al-Malik b. Marwn in 72/691-2,38 although a sizeable

24. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 24952; 1916: 28486. Richard Bulliet (1979: 106) also suggests that the early Syrian

ulema included in later biographical dictionaries were mostly Arab. However, his conclusion is based upon the

preponderance of ulema from inland as opposed to coastal Syria, and he assumes that people from an area including

Damascus should be presumed to be Arab. The precedence of the Bedouin in conversion to Islam is also indicated,

with bibliography, by Humphreys (2010a: 49).

25. Al-Baladhuri 1916: 285; 1957: 250. I have emended ittis translation.

26. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 185; 1916: 209.

27. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 205; 1916: 232.

28. Early Muslim aversion to farming is indicated by a number of hadith analyzed by M. J. Kister (1997, 4:

27086). That nomads did not overwhelmingly adopt Islam at the time of the initial conquests is indicated by the

existence of a Syrian Orthodox bishop of the Arabs consecrated in 686 who died in 724 (Tannous 2008).

29. For example, regarding the garrisons of the sea coast under Umar b. al-Khab or Uthmn b. Affn, see

al-Baladhuri 1957: 173; 1916: 195. In this regard it is revealing that several of the hadith analyzed by Kister (1997,

4: 28690) presume that Muslims are urban dwellers.

30. Walker (2013: 14849) indicates that the conversion of a church into a mosque was quite rare in central

Jordan; abandoned churches would become private residences far more commonly.

31. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 189; 1916: 201; al-Muqaddasi 1906: 156; 1994: 144; Yaqut al-Hamawi 1990, 2: 348.

32. Khalek 2011: 9697. Joseph Nasrallah (1992) cites the standard sources for the received narrative, although

with no critical engagement.

33. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 200; 1916: 226.

34. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 181; 1916: 204.

35. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 175; 1916: 196.

36. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 195, 226, 232; 1916: 220, 255, 262.

37. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 16061, 201; 1916: 180, 228.

38. For example, al-Muqaddasi 1906: 169; 1994: 154. A recent architectural history of the building is Grabar

2006.

Carlson: The Geography of Islamization in Syria, 6001500

799

earlier mosque in the city was mentioned by a Latin pilgrim who visited the city around

680.39 Al-Haraw and Yqt al-amaw would include Bethlehem outside Jerusalem as a

city that acquired a mosque under the second caliph Umar b. al-Khab, but the fact that

al-Muqaddas did not mention such an edifice, although he was a native of the area and seems

disposed to mention all the mosques he knew, suggests that it was a more recent creation.40

How long did Christians and Muslims share sanctuaries? According to al-Baldhur,

the transformation of the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Damascus into the Umayyad

Mosque took place during the reign of the caliph al-Wald b. Abd al-Malik (d. 96/715), indicating that the mosque in the capital city of the caliphate was shared for a few generations,

continuing even after the construction of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.41 The cathedral

of im was divided between Christians and Muslims even longer, although it is not possible to say with certainty exactly how long on the basis of the geographical literature. Ibn

awqals statement, In [im] is a church, part of which is the Friday mosque, and half

of it belongs to the Christians,42 may indicate that it was still divided in the middle of the

tenth century. On the other hand, his pupil al-Muqaddas later in the century only refers to

the division at the time of the conquest.43 A story reported later by Yqt refers to a young

Muslim playing in the church with a ball, and it happened that the ball entered the mosque,

showing that the building was certainly divided, perhaps as late as the 170s/ca. 790.44 The

early construction of mosques in the major cities of Syria added an Islamic focus to urban

centers, but did not necessarily exclude or replace non-Muslims.45

expanding into the countryside: village mosques and rural shrines

Outside of the major cities, the slower progress of Islamization is shown by the delayed

diffusion of rural mosques and Muslim shrines. In the tenth century Ibn awqal remarked

that the region of Filasn had around twenty minbars [i.e., mosques] despite its small size.46

On the one hand, twenty mosques would cover all the major cities but only a few of the

many villages. That only very large villages possessed mosques is indicated not long afterward by al-Muqaddas, who said of Filasn, In this district are large villages with their

own mosques, and these are more populous and more flourishing than most of the cities

of al-Jazra.47 Indeed, al-Muqaddas listed twenty-one mosques in the region of Filasn.48

39. Adamnan 1958: 4243.

40. Al-Muqaddasi 1906: 172; 1994: 156; al-Harawi 1953, 1: 29; 2: 70; 2004: 7677; Yaqut al-Hamawi 1990,

1: 618.

41. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 171; 1916: 19192.

42. Ibn Hawqal 1964a: 162; 1964b, 1: 173.

43. Al-Muqaddasi 1906: 156; 1994: 144.

44. Yaqut al-Hamawi 1990, 2: 349.

45. Lapidus (1969: 57) asserted that in this period across the Muslim-ruled world Muslim cities were isolated

in Christian, Zoroastrian, or pagan countrysides, but this view neglects both the nomadic Arab Muslims and the

fact that cities taken over by Muslim conquerors continued to have a non-Muslim majority for an indeterminate

period.

46. Ibn Hawqal 1964a: 159; 1964b, 1: 169.

47. Al-Muqaddasi 1906: 176; 1994: 160, where al-Jazra is translated as the Arabian Peninsula, but the

region referred to by this phrase is more commonly upper Mesopotamia. Andr Miquels French translation (1963:

208) likewise rendered al-Jazra with reference to Arabia, and while it is the more likely interpretation, I have

reverted to transliterating the Arabic to preserve the ambiguity.

48. Al-Muqaddas mentioned mosques in al-Ramla, Djn nearby, Jerusalem, Jabal Zayt (Mount of Olives)

outside Jerusalem, Hebron, al-Yaqn outside Hebron, Gaza, Asqaln, Yf, Arsf nearby, Qaysriyya, Nbulus,

Jericho, Ammn, Ludd outside al-Ramla, Kafr Sb on the road to Damascus, qir on the road to Mecca, Yubn

800

Journal of the American Oriental Society 135.4 (2015)

Of these, it is clear that only two (Jabal Zayt and al-Yaqn) are properly rural, and seven

are described as being in villages (qur), namely, Hebron, Ludd, Kafr Sb, qir, Yubn,

Amaws, and Kafr Sallm.

On the other hand, Ibn awqals concessive clause (despite its small size) seems to indicate that in the diffusion of mosques Filasn was more Islamized than Ibn awqal expected,

which may hint that throughout the rest of Syria at that time there were not many village or

rural mosques. Since the number of Muslims that a mosque could serve might range from

tens to thousands, it is impossible to estimate the Muslim population of Filasn based on this

figure, but it does suggest that in the mid-tenth century only the largest villages would have

had a Muslim architectural presence.49 This suggests that after the initial conquests Islamization was a process of diffusion from the cities to the villages and countryside.

Away from the coast, the roads connecting major cities overland were meeting-places for

Muslims and non-Muslims, and thus conduits of Islamization. Al-Muqaddas listed six large

villages possessed of their own mosques, of which he located three (Kafr Sb, qir, and

Kafr Sallm) on main roads.50 Of the other three, two were also on important roads: Yubn

is between Yf and Asqaln on the coastal road, and Amaws is between al-Ramla and

Jerusalem. Of the six villages, only Ludd is not on a major road, but in the late tenth century

it was essentially a suburb of the district capital al-Ramla; according to al-Muqaddas, it

lies about a mile from al-Ramla. There is here a great mosque wherein large numbers of

people assemble from the capital, and from the villages around.51 By contrast, he reported

no mosques in villages or cities away from roads, the coast, or the outskirts of the capital

al-Ramla.

If the district of Filasn was probably the Syrian district with the greatest concentration

of mosques, al-Muqaddas is explicit that it also had a greater number of rural shrines than

other districts, especially in the neighborhood of Jerusalem, and he asserted that he had listed

most of them.52 The most striking feature of the list he gave, however, is how few of them

celebrate specifically Muslim figures.53 The majority of these shrines and holy sites pertain

to figures of ancient Jewish history who were venerated in common by Jews, Christians, and

Muslims (although often not Samaritans): Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Rachel, Job, Moses, Saul,

David, Uriah, Solomon, and Jeremiah, some with multiple sites. A smaller number pertain to

Jesus, Mary, and John the Baptists father Zakariyy.54 Of distinctively Muslim sites possibly outside of major cities, he referred only to Umars mosques, which presumably would

include the mosque in commemoration of the caliph on Jabal Zayt outside Jerusalem and

al-Yaqn Mosque outside Hebron. Even his vague reference to the shrines of the prophets

near the coast, Amaws between al-Ramla and Jerusalem, and Kafr Sallm near Qaysriyya on the coastal road; see

al-Muqaddasi 1906: 16566, 16877, 182; 1994: 151, 15360, 165.

49. Humphreys (2010b: 53334) suggests a more rapid Islamization of Syria south of im than in the north or

in al-Jazra. While this may be the case, the restriction of mosques to cities and a few large villages implies regions

devoid of Muslim inhabitants. If al-Muqaddass list of mosques is comprehensive, then the city of Bayt Jibrl

between Hebron and Asqaln not only lacked a mosque, but was not within 20 km of a mosque. The hill country

between Jerusalem and Nbulus also lacked any mosques, in precisely the area found by Ellenblum (1998: 283) to

be dominated by Christian settlements two centuries later.

50. Al-Muqaddasi 1906: 17677; 1994: 160.

51. Al-Muqaddasi 1994: 160; 1906: 176.

52. Al-Muqaddasi 1906: 184; 1994: 167.

53. His list is found in al-Muqaddasi 1906: 151; 1994: 138.

54. Josef Meri (2002: 195201, 21012, 24350) discusses such shared shrines; Christopher MacEvitt (2008:

12630, 13234) discusses the sharing of churches between Franks and Middle Eastern Christians, which could be

every bit as awkward.

Carlson: The Geography of Islamization in Syria, 6001500

801

shows a Muslim approach to pre-Islamic history. It is therefore unclear whether the many

shrines to pre-Islamic personages were in any way distinctively Islamic, or whether they

were shared between Muslims and non-Muslims, perhaps even in the possession of the latter.

Later geographical sources record increasing numbers of shrines.55 The Persian poet and

philosopher Nir-i Khusraw, whose account of his travels tends toward brevity, indicated

that he turned aside from his travels down the coastal road in order to visit a mountain

where various prophets shrines are located between Acre and Tiberias.56 But the majority

of these religious sites were dedicated to historical figures shared by Jews, Christians, and

Muslims alike: Esau, five sons of Jacob, the father-in-law and wife of Moses, the mother of

Moses, Joshua b. Nun, Jonah, and Ezra.57 Another shrine was dedicated to the legendary

founder of Acre, namely Akk, while two others of presumably Muslim origin were dedicated

to the pre-Islamic figures Hd and Dh l-Kifl. A mosque known as the Jasmine Mosque

was situated to the west of Tiberias, while the only shrine dedicated to an earlier Muslim was

the tomb of Ab Hurayra south of Tiberias, and the Persian traveler indicated that pilgrimages to it were impossible because the children of the local Shiite population harassed wouldbe visitors.58 Even more significantly, he described and explained the Spring of the Cows

(ayn al-baqar) outside Acre without mentioning the mashhad of Al, which geographers

from Al al-Haraw onward mention there.59

Over a century later, Al al-Haraw recorded clear instances of shrines shared between

Muslims and non-Muslims. For example, he mentioned outside of the Jewish Gate of Aleppo

a stone at which votive offerings are made and upon which rosewater and sweet fragrances

are poured. Muslims, Jews and Christians hold it in regard. It is said that beneath it is the

tomb of one of the prophets ... or the saints. God knows best.60 He also referred to shrines

dedicated to pre-Islamic figures such as Joshua b. Nun, Alexander the Great, and the mother

of John the Baptist, in greater number than indicated by al-Muqaddas.61 On the other hand,

in his record of the pilgrim shrines he encountered in his travels through Syria in the late

twelfth century, shrines to figures of early Islamic history have greatly increased. In the countryside around Damascus he recorded the tombs of Diya al-Kalb (who also has a tomb near

Tiberias and a tomb at al-Fus), ujr b. Ad, Zumayl b. Raba, Raba b. Amr, Khlid b.

Sad, Sad b. Ubda al-Anr (although al-Haraw rejected the validity of this tomb), Umm

Kulthm, Mudrik, Kannz, Shaykh Sulaymn al-Drn, Ab Muslim al-Khawln, Umm

tika, and uhayb al-Rm (the last two likewise rejected by al-Haraw).62 By al-Haraws

time in the late twelfth century, the Gha around Damascus had the highest concentration of

rural shrines. By contrast, he complained that due to Crusader rule, in Ascalons cemetery

are many saints, and Successors whose tombs are unknown; the same with Gaza, Acre, Tyre

and Sidon and all of the towns of the coastal plain.63 And it is noteworthy that he was

55. For discussion of the increasing number of Muslim shrines in medieval Syria, see Talmon-Heller 2007b:

19095; Meri 2002: 25762.

56. Nasir-i Khusraw 1986: 17; 1975: 26.

57. Nasir-i Khusraw 1975: 2631; 1986: 1719.

58. Nasir-i Khusraw 1975: 2931; 1986: 1819.

59. Nasir-i Khusraw 1975: 2526; 1986: 17.

60. Al-Harawi 2004: 1213; 1953, 1: 4; 2: 9.

61. Al-Harawi 1953, 1: 7, 23; 2: 14, 16, 59; 2004: 16, 66.

62. Al-Harawi 1953, 1: 1113; 2: 2732; 2004: 2430. For Diya al-Kalbs other tombs, see al-Harawi 1953,

1: 20, 37; 2: 52, 87; 2004: 40, 98.

63. Al-Harawi 2004: 82; 1953, 1: 33; 2: 76.

802

Journal of the American Oriental Society 135.4 (2015)

unable to list any Muslim shrine in the hinterland around Aleppo, despite wishing to exalt

the city of his final patron.64

Muslim devotion to pre-Islamic figures and prayers at shrines devoted to them were not

problematic, as from a common Muslim perspective the prophets of old had preached Islam,

but the Jews and Christians had corrupted the message. Far from a religious difficulty, shared

shrines provided an opportunity for Muslims to have pilgrimage sites maintained by nonMuslims, and an opportunity for non-Muslims to convert more easily to Islam without forsaking the loca sancta and past holy figures upon which they relied. The progression of

reports from al-Muqaddas to Nir-i Khusraw to al-Haraw, however, seems to indicate that

the creation of specifically Muslim holy sites in rural areas was a slow process, perhaps only

beginning in the tenth century around the time of the Byzantine reconquest, and by no means

complete by the end of the Crusader period. In particular, the late appearance of the tombs

of Companions in rural areas even around Damascus, and often with questions regarding

their authenticity, suggests that funereal veneration of the Companions was a late stage in

the development of a specifically Islamic landscape.65 The dedication of shrines to figures

revered by multiple religions was an important step in the conversion of the rural population,

but it was five centuries before distinctively Islamic shrines are attested in most of Syrian

countryside.

syria divided: byzantine reconquest and crusader states

When Nikephoros Phokas entered Syria at the head of a Byzantine army in 350/962,

establishing Antioch as a Byzantine outpost in 358/969, Syria was already accustomed to

marauding armies. Neglected as a province after the caliphal capital moved from Damascus to Baghdad in the eighth century, by the later ninth century central Abbsid authority

was waning and Syria was contested between various Muslim rulers such as the lnids,

Ikhshdids, and amdnids. The new element introduced by the Byzantine reconquest of

northern Syria was rule by Christians in a territory from which it had been absent for over

three centuries. From the 350s/960s until the Crusader stronghold at Acre was captured by

the Mamluk armies of Egypt in 690/1291, Syria was divided between multiple Muslim and

Christian rulers, with a brief hiatus between the Byzantine loss of Antioch in 477/1084 and

the Crusader conquest of the same city in 491/1098. This division of Syria widened the gap

in Islamization between different portions of the region, reversing the coastal cities early

adoption of mosques while perhaps encouraging the development of rural Islamic shrines.

The earliest geographers to observe the Byzantine reconquest painted the invaders as little

more than raiders and deplored the sorry state of Islam that permitted them to succeed. Ibn

awqal recorded Greek attacks on im, Aleppo, Qinnasrn, Jabala, in Barzya, Antioch,

al-adath, Marash, al-Hrniyya, al-Iskandarna, and he blamed the enemys success on

failures of Muslim religious zeal.66 He lamented over Antioch,

64. Al-Harawi (1953, 1: 56; 2: 1011; 2004: 1214) mentioned various Muslim shrines in and around Aleppo

itself, but apart from a tomb in the village of Rn that he identified as belonging to Quss b. Sida al-Iyd, all of

the other shrines were dedicated to Jewish or Christian figures. Indeed, he reported that even the shrine of Rn was

alternatively identified as belonging to Christian figures.

65. For a contrary view, Nancy Khalek (2011: 123) acknowledges that a specifically Islamic sacred landscape

was slowly being built up over centuries, but contends that Tombs of fallen Companions who had served in the

conquests were the first elements of that new environment. Meri (2002: 25758) suggests that early monuments to

fallen Companions had very little connection to later medieval pilgrimage shrines.

66. Ibn Hawqal 1964a: 16265, 167; 1964b, 1: 17377, 17980.

Carlson: The Geography of Islamization in Syria, 6001500

803

The enemy has overcome it and possessed it, and before its conquest it had become disordered in

the hands of the Muslims, and now it is more severely disordered and abased.... Around it there

are sultans, Bedouin, lords, and kings, for each of whom his today distracts him from attention

to his tomorrow, and what is forbidden him and his vanities distract him from what God Most

High enjoined and the governance and leadership incumbent upon him.67

The Byzantine invasion of im he credited to their confusion (khabl) and luxury

(yasr), while in Barzyas surrender he ascribed to, among other factors, their lack of

faith (qillat al-mn).68 Al-Muqaddas devoted less space to the presence of Byzantines

than his predecessor, because he consciously excluded from his description those portions

of Syria ruled by the Christians,69 but he described a climate of fear among the Muslims in

Syria: The people live in dread of the [Byzantine army], as if they were in a foreign land,

for their frontiers have been ravaged, and their border defenses shattered.70 The Muslim

geographers of the tenth century depicted the division of Syria between Christian and Muslim rulers as a religious catastrophe.

Nevertheless, these same geographers indicated that most Muslims in the areas now under

Christian rule were content to accept the new system. Ibn awqal concluded his section on

Syria with a pessimistic prediction that Byzantine rule and the jizya levied on Muslims would

lead many of the people of Syria to abandon Islam: Most of its people remained, while they

accepted jizya from them, and I think they will convert to Christianity, disdaining the humiliation of the jizya and greedy to obtain provisions for honor and comfort.71 Al-Muqaddas

confirmed Ibn awqals dire predictions: Some [of the people] have apostasized, while

others pay tribute (jizya), putting obedience to created man before obedience to the Lord

of Heaven. The general public is ignorant and churlish, showing no zeal for the [struggle],

no rancour towards enemies.72 The new Christian rulers were evidently inclined to treat

their Muslim subjects much as their Muslim predecessors had treated Christian subjects: the

term jizya probably refers to a Muslim-specific head tax, analogous to the poll tax on nonMuslims levied by the caliphs. Although the Byzantine army reportedly destroyed mosques,

such attacks seem to have occurred as an element of capturing and plundering a city, and

there is no indication that the new Christian overlords prevented local Muslim rulers from

repairing mosques.73

Muslim travelers through the Crusader states in the twelfth century adopted a curiously mixed attitude toward the Frankish rulers.74 Christian rule in lands formerly under

Muslim control was clearly regarded as a shameful fact, as Al al-Haraw complained to

Prophet Muammad when the latter appeared to him in a dream in the mosque in Asqaln

in 570/1174, before al al-Dns conquest of the city.75 Ibn Jubayr polemicized against

67. Ibn Hawqal 1964a: 165.

68. Ibn Hawqal 1964a: 162, 164; 1964b, 1: 173, 176.

69. Al-Muqaddasi 1906: 152; 1994: 140.

70. Al-Muqaddasi 1994: 139; 1906: 152.

71. Ibn Hawqal 1964a: 172.

72. Al-Muqaddasi 1994: 139; 1906: 152. The translators rendering of jihd as holy strife is problematic and

has been changed here to the more neutral term struggle. Andr Miquel (1963: 154 n. 52) interpreted this sentence

as an allusion aux Juifs et au Chrtiens, sujets protgs, in defiance of the context.

73. For example, in the city of Aleppo; see Ibn Hawqal 1964a: 163; 1964b, 1: 174.

74. For one synthesis of the evidence for Muslim subjects of the Crusader states, see Kedar 1990. Kedar (p. 145)

presumes that the majority of the population under Frankish rule was Muslim, while Christopher MacEvitt (2008:

12), who analyzes the Frankish treatment of their Eastern Christian subjects, asserts without citation that Christians

were the majority of the population in northern Syria, a term that for him includes northwestern Mesopotamia.

75. Al-Harawi 1953, 1: 32; 2: 76; 2004: 82.

804

Journal of the American Oriental Society 135.4 (2015)

Muslims who chose to remain in lands ruled by non-Muslims: There can be no excuse in the

eyes of God for a Muslim to stay in any infidel country.76 On the other hand, both al-Haraw

and Ibn Jubayr often emphasized how little the Franks had interfered with Muslim religious

practice. Thus, al-Haraw indicated three times that the Crusaders did not damage various

aspects of the Muslim sanctuaries in Jerusalem and Bethlehem.77 Ibn Jubayr, for his part,

ascribed to Gods intervention the preservation of part of the main mosque at Acre and part

of Ayn al-Baqar outside the city.78 He also indicated that the Muslims of Tyre were treated

better than those of Acre, and that they lived under a written guarantee of safety (amn),79

while Muslim peasants enjoyed greater security under Frankish rule than they would in lands

ruled by Muslims.80 Both of these authors clearly expected greater harassment from the

Franks than they received.81

Ibn Jubayr in particular laid out the Crusaders treatment of their Muslim subjects, and

his description mirrors the treatment of Christians by Muslim rulers. When the Franks captured Acre, Mosques became churches and minarets bell-towers, but just as the Byzantine

cathedrals of Damascus and im were divided between Christians and Muslims in the seventh century, so Acres Friday mosque and the shrine at Ayn al-Baqar were shared after the

Crusaders conquest of the city.82 He explicitly likened the tax levied upon Muslims under

Frankish rule with that levied upon Christians under Muslim rule: The Christians impose a

tax on the Muslims in their land which gives them full security; and likewise the Christian

merchants pay a tax upon their goods in Muslim lands. Agreement exists between them, and

there is equal treatment in all cases.83 In his polemic against Muslims choosing to dwell

in lands ruled by non-Muslims, Ibn Jubayr alluded to the head-tax upon Muslims as the

abasement and destitution of the capitation.84 He gave the rate of the jizya as 1.25 dinars, as

well as half of the crops.85 However, a lighter tax could be assessed on travelers: Ibn Jubayr

indicated that when he first entered lands under Crusader rule, the jizya he paid was levied

primarily upon Muslims from the Maghrib, due to a prior attack by a group of western Muslims on a castle of the Franks, and that other Muslims were not taxed in this manner.86 The

Andalusi traveler had earlier marveled at the security of both Christian and Muslim travelers

despite the ongoing wars between al al-Dn and the Crusaders,87 and he was surprised,

76. Ibn Jubayr 1952: 321; 1981: 252.

77. Al-Harawi 1953, 1: 2526, 29; 2: 6365, 70; 2004: 72, 76.

78. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 249; 1952: 31819.

79. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 250, 252; 1952: 319, 321.

80. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 24748; 1952: 31617.

81. These views counterbalance the evidence of Usma Ibn Munqidh, whose Kitb al-Itibr mentions nonMuslims primarily in narratives of battles with Franks. But his book is almost exclusively concerned with elites,

whether Muslim or Frankish, and battles loom large among the anecdotes related. Even Ibn Munqidh, however,

indicated that the Franks who had been in Syria longer harassed Muslims less; see Ibn Munqidh 1930: 13435, 140;

2008: 147, 153.

82. Ibn Jubayr 1952: 318; 1981: 249. Ibn Jubayrs description of sharing the mosque over Ayn al-Baqar seems

to refute al-Haraws contention (1953, 1: 22; 2: 57; 2004: 44) that the Franks intended to make it a church, but were

thwarted by Al b. Ab lib mystically killing their night-watchmen. Yqt (1990, 4: 199) likewise alluded to the

fact that Ayn al-Baqar was venerated by Muslims and non-Muslims alike, including Jews in his list of worshippers

there.

83. Ibn Jubayr 1952: 301; 1981: 235.

84. Ibn Jubayr 1952: 322; 1981: 252.

85. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 247; 1952: 316.

86. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 247; 1952: 316.

87. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 23435; 1952: 300301.

Carlson: The Geography of Islamization in Syria, 6001500

805

and horrified, at the level of social integration that could be achieved between Christians and

Muslims in Syria.

Despite Ibn Jubayrs assertions of the security of non-combatants in Syria even with the

ongoing wars, geographical texts written during Syrias divided period frequently mention

raiding by both Muslims and Christians. Ibn awqal complained of raids not only by the

Byzantine army, but also by the Bedouin who surrounded im after the Byzantine invasion.88 He indicated that Byzantine incursions led to an increased use of the inland route

from Damascus northward, where a sign of the degeneracy of the age was the dominance

of the Bedouin over the governors, and he expected all travel to cease.89 Ibn Jubayr himself

noted that the khns where travelers lodged in Syria were all heavily fortified, and that the

road between im and Damascus was largely uninhabited except for a few large villages at

the caravan stops.90 He mentioned Frankish raiding possibilities from in al-Akrd to im

or am, as well as on the road from Damascus to the coast.91 Although he presented al

al-Dns capture of Nbulus in 580/1184 as a glorious conquest for Islam, the attack on the

unwalled village was clearly more in the nature of a plundering raid.92 While both Muslim

and Crusader rulers may have avoided plundering merchant caravans, on which they found it

easier to assess commercial taxes, the rural and semi-rural settled population probably fared

worse at their hands.

Nevertheless, significant demographic shifts happened during Syrias divided period.

The Byzantine reconquest brought Greek rule back to Syria, but it also brought Armenians

who settled in northern Syria and along the Cilician coast. Ibn awqal already mentioned

that when the Byzantines conquered Malaya in 319/931, they peopled it with Armenians.93

Al-Muqaddas noted Armenian control of Jabal al-Lukkm on the northern edge of Syria.94

Two centuries later Yqt indicated Armenian control not only over Cilician cities such as

Ayn Zarb, al-Hrniyya, Ssiyya, and arss, but also a dominantly Armenian population

in the fortress of Tal Bshir two days north of Aleppo and the surrounding district of Nahr

al-Jawz between Aleppo and al-Bra (modern Birecik) on the Euphrates.95 Armenians would

remain a substantial portion of the population in this region throughout Ottoman times.

On the other hand, the Shiite population of Syria grew during and after the Shiite century, in part due to Fimid interests in Syria. Writing after the first invasions but before the

Fimid dynasty held any possessions there, al-Muqaddas mentioned Shiite populations only

in Tiberias, Ammn, half of Nbulus, and half of Qadas north of Tiberias.96 A half-century

later Nir-i Khusraw referred to the Shiite population and Egyptian garrison in Tripoli, as

well as other Shiite groups in Tyre and in the countryside west of Tiberias, where they prevented Sunni pilgrims from visiting the tomb of Ab Hurayra.97 Ibn Jubayr remarked on the

Ismaili castles in Mount Lebanon, and formerly in al-Bb between Aleppo and the Euphrates.98 Indeed, he indicated the broad diffusion of Shiites in Syria: They are more numerous

88. Ibn Hawqal 1964a: 16263; 1964b, 1: 173.

89. Ibn Hawqal 1964a: 165; 1964b, 1: 176.

90. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 205, 20910; 1952: 264, 269.

91. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 206, 209, 246; 1952: 265, 268, 315.

92. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 245; 1952: 314.

93. Ibn Hawqal 1964a: 166; 1964b, 1: 179.

94. Al-Muqaddasi 1906: 189; 1994: 172.

95. Yaqut al-Hamawi 1990, 2: 47, 213; 3: 338; 4: 33, 201; 5: 446.

96. Al-Muqaddasi 1906: 179; 1994: 16263.

97. Nasir-i Khusraw 1975: 21, 24, 3031; 1986: 13, 16, 19.

98. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 202, 206; 1952: 25960, 264.

806

Journal of the American Oriental Society 135.4 (2015)

than the Sunnis, and have filled the land with their doctrines.99 As an exception in northern

Syria he praised Manbij, whose population he indicated was entirely Sunni, so that through

them the town is undefiled by those dissident sects and corrupt beliefs that are found in most

of this country.100 The Ismaili castles in the mountains of western Syria and Lebanon would

become a refrain of later geographers.101

Although most Muslim geographers pay little attention to the Jewish population, the travelogue of Benjamin of Tudela gives approximate Jewish populations for many cities of Syria.

Although no other geographical work documents the presence of Jewish communities so

extensively, such indications as do exist seem to indicate a marked decline in the Jewish

population of Filasn and the coastlands in this period, relative to much larger Jewish populations in the inland portions of central and northern Syria. Thus, al-Muqaddas had complained of the greater numbers of Jews and Christians than Muslims in his native Jerusalem

in the late tenth century, but two centuries later Benjamin of Tudela indicated a population

of only 200 Jewish men in the city.102 Al-Baldhur mentioned that Muwiya had settled

Tripoli with Jews in the seventh century, but Benjamin of Tudela in the twelfth century

only indicated that a recent earthquake had killed many Jews and gentiles; his text does not

indicate how many Jews remained in the city.103 Al-Baldhurs figure of 20,000 Jews in

Qaysriyya, alongside 700,000 soldiers and 30,000 Samaritans, is clearly exaggerated even

beyond the extent of the likely influx of rural refugees, but Benjamin of Tudelas indication of about 10 Jewish men in the city still indicates a dramatic decline.104 No city under

Crusader rule had a larger Jewish population than Tyre, with about 500 Jewish households.105

The figures given for Jewish populations of cities still under Muslim rule stand in stark

contrast: 3,000 for Damascus, 5,000 for Aleppo, even 2,000 each for Tadmur on the edge of

the desert and Raba on the Euphrates.106 This discrepancy and the fact that the Yeshiva of

Jerusalem was headquartered in Damascus indicate a preference for medieval Syrian Jews

to relocate outside of Crusader control, resulting in a much smaller Jewish population for

coastal cities and Filasn.107

The religious character of the rural population also shifted markedly in this period. Ibn

Jubayrs remarks on Crusader rule over Muslims presumed that many of the Muslims were

peasants, a point he made explicit with regard to the population around Bniys between

Damascus and Tyre.108 Ibn Jubayrs remarks should not be taken to indicate that the rural

population throughout Syria had largely converted to Islam, however; the contrary is indicated by his reference to the entirely Christian town of Qra south of im, as well as his

99. Ibn Jubayr 1952: 291; 1981: 227.

100. Ibn Jubayr 1952: 259; 1981: 201.

101. Yaqut al-Hamawi 1990, 2:77, 119; 3: 243; 4: 535; 5: 168; al-Dimashq 1866: 200, 2023, 208, 209; 1874:

269, 274, 28284, 286; Ibn Baa 1964, 1: 4445; 1958, 1: 106; Abu l-Fida 1840, 1: 22930; 2,2: 7.

102. Al-Muqaddasi 1906: 167; 1994: 152; Benjamin of Tudela 1907: 22, . As for the latter, the numbers given

in the Hebrew are usually of yhm, which is ambiguous as to whether it includes women or refers only to Jewish

men. Despite the term being translated as Jews throughout, it is suggested (1907: 16 n. 2) that only male heads

of households were in view.

103. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 174; 1916: 195; Benjamin of Tudela 1907: 17, .

104. Al-Baladhuri 1957: 192; 1916: 217; Benjamin of Tudela 1907: 20, .

105. Benjamin of Tudela 1907: 18, .

106. Benjamin of Tudela 1907: 3032, 34, ,.

107. Benjamin of Tudela 1907: 30, .

108. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 24648; 1952: 31517.

Carlson: The Geography of Islamization in Syria, 6001500

807

description of the respect with which Christian peasants treated Muslim hermits.109 The

peasants veneration for Muslim holy men no doubt contributed to their progressive conversion to Islam, as did the rural shrines shared between Muslims and non-Muslims, such as

Ayn al-Baqar outside Acre mentioned by Ibn Jubayr and Yqt, the tomb of the unknown

prophet outside Aleppo, and the shrines visited by Nir-i Khusraw between Acre and Tiberias.110 The proliferation of shrines dedicated to specifically Muslim figures during this

period, such as those enumerated by al-Haraw, may have been partly due to the loss of

many urban mosques to Byzantine and Crusader conquests, but it was also partly due to

the increase of Shiite Muslims who sometimes took over an urban mosque and sometimes

dedicated rural shrines to Al b. Ab lib.111 Nir-i Khusraw described specifically Shiite

shrines around Tripoli: The people of this city are all Shiites, and the Shiites have built

nice mosques in every land. They have edifices there like caravanserais, which they call

mashhads, but no one lives in them. Outside the city of Tripoli there is not a single structure

except for a couple of mashhads.112

Nor was the convergence of religious topography limited to rural settings. Ibn Jubayr

mentioned that the main mosque of Acre was shared between Christians and Muslims,113 and

al-Haraw noted that the shrine around the tombs of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Sarah was

administered by Greek Christians in the days of Frankish rule, although he as a Muslim

visited it.114 Earlier Nir-i Khusraw had commented that Muslims as well as Christians

and Jews came as pilgrims to Jerusalem.115 During Crusader rule the Dome of the Rock in

Jerusalem was converted into a church, and al-Haraws account of his visit to the building

mentions icons of Solomon and Christ.116 Despite, or perhaps because of, this sharing of the

Umayyad edifice, al-Haraw is the earliest geographer to describe the Rock as the place from

which Muammad ascended on his night journey; Ibn awqal and al-Muqaddas had identified the stone as the Rock of Moses.117

109. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 209, 23334; 1952: 269, 300. Ellenblum (1998: 283) also concluded on the basis of

archaeological evidence that in the twelfth century Palestine still had large rural areas dominated by Christians

and other rural areas dominated by Muslims. The former included western Galilee around Acre and the hill country north of Jerusalem, while the latter included eastern Galilee and central Samaria. Kedar (1997b: 138) pointed

out that Ellenblums finding of religious segregation in Crusader-ruled Palestine is consistent with the absence of

evidence for personal ties between Muslim peasants and the Franks according to an Islamic hagiographic text. It

may, however, be objected that Kedars interpretation is an argument from silence; reporting such relationships may

not have served the hagiographers purpose.

110. See nn. 5758, 60, and 82, above. Although Ibn Jubayr (1981: 254; 1952: 324) mentions very few shrines,

he likewise mentions tombs dedicated to ancient Jewish figures around Tiberias.

111. Ayn al-Baqar outside Acre was dedicated to Al b. Ab lib, for example (al-Harawi 1953, 1: 22; 2: 57;

2004: 44). Ibn Baa (1964, 1: 39; 1958, 1: 94) mentioned a Shiite mosque in the village of Sarmn southwest of

Aleppo.

112. Nasir-i Khusraw 1986: 13; 1975: 21.

113. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 249; 1952: 318.

114. Al-Harawi 1953, 1: 3031; 2: 7273; 2004: 78.

115. Nasir-i Khusraw 1975: 3435, 6263; 1986: 21, 3738.

116. Al-Harawi 1953, 1: 2425; 2: 6263; 2004: 70; Grabar 2006: 16069. The Dome of the Rock is likely the

small mosque that the Franks had converted into a church mentioned by Usma Ibn Munqidh (2008: 147; 1930:

13435), in which he would pray with permission from the Templars.

117. Ibn Hawqal 1964a: 158; 1964b, 1: 168; al-Muqaddasi 1906: 151; 1994: 138; al-Harawi 1953, 1: 24; 2: 62;

2004: 70. Miquel (1963: 14748 n. 15) supplied other possible identifications of the Rock of Moses, without ruling

out the identification as the Dome of the Rock. Indeed, al-Muqaddas (1906: 169; 1994: 154) identified a separate

Dome of the Ascent (sc. of Muammad; qubbat al-mirj) near the Dome of the Rock, while Nir-i Khusraw

(1975: 43; 1986: 26) claimed that Muammad ascended from al-Aq Mosque, which he distinguished from the

Dome of the Rock.

808

Journal of the American Oriental Society 135.4 (2015)

If the appearance of Muslim peasants broke down the older division between Muslim

nomads and the non-Muslim sedentary population, the partition of Syria between Christian

and Muslim rule generated new axes of Islamization between different regions within Syria.

The Byzantine reconquest and the accompanying influx of Armenians probably resulted in

the northern edges of Syria containing a higher proportion of Christians than areas further

south, such as the Gha around Damascus. Ibn Jubayr noted that most villages of the Gha

had a bathhouse, while Yqt described the village of Imm between Aleppo and Antioch as

entirely Christian in his day, although he quoted Ibn Bulns statement that it had a mosque

in the eleventh century.118 If the Byzantine reconquest introduced a north-south axis, the

Crusades resulted in an east-west distinction between coastal areas and inland. This is particularly significant since in the earlier centuries of Islam, the garrisons on the Syrian coast had

resulted in an earlier Islamization in precisely the areas where the Crusaders now ruled. But

al-Haraw complained of the inability to identify the tombs of early Muslims in the coastal

cities due to the Frankish regime.119 The noteworthiness of the level of rural Islamization in

the Gha to Ibn Jubayr may reflect the fact that Damascus was one of the few cities of Syria

not sacked by the Byzantines or the Crusaders.

the return to muslim rule in mamluk syria

The Mamluk conquests of the last Crusader states on the Levantine coast reunited Syria

under Muslim rule, although the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia continued to exist as a troublesome vassal of the sultans in Cairo until 776/1375. But three centuries of divided rule

had left Syria much more regionally diverse and the non-Muslim populations much reduced.

While Crusader rule of the coast had encouraged Christian residence there, the Mamluk

conquests were accompanied by deliberate destruction of the coastal settlements. As a result,

most references to Christians in the geographical works of the Mamluk period situate them

in northern Syria, whether in urban or rural settings. Most cities of northern Syria had a

non-Muslim population, and some large towns on major roads continued to be entirely or

primarily Christian at least into the fourteenth century.

Unlike the first Muslim conquerors of Syria over six centuries earlier, the new Mamluk

rulers did not fortify the coast, but rather depopulated it to a significant degree and rendered

it indefensible. The purpose was evidently not to prevent a new Crusader invasion, but to

prevent the Crusaders from being able to hold anything on the mainland. Thus, according to

Ibn Baa, the Mamluk sultan Baybars (r. 658676/12601277) destroyed the walls around

Antioch when he captured the city in 666/1268.120 Tripoli was demolished by the Mamluks

in 688/1289 and refounded away from the coast.121 Jubayl and Beirut may have fared somewhat better, with Ab l-Fid indicating that the former had a Friday mosque and Ibn Baa

indicating the same for the latter.122 On the other hand, the ports that were the last Crusader

strongholds, Tyre and Acre, were completely ruined after the Mamluk conquest, according

118. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 224; 1952: 288; Yaqut al-Hamawi 1990, 4: 177.

119. He made a similar complaint regarding Crusader-ruled Jerusalem, which he visited before it was conquered by al al-Dn (al-Harawi 1953, 1: 28, 33; 2: 68, 76; 2004: 74, 82).

120. Ibn Baa 1964, 1: 43; 1958, 1: 103.

121. Al-Dimashq 1866: 207; 1874: 282; Abu l-Fida 1840, 1: 253; 2,2: 30; Ibn Baa 1964, 1: 37; 1958,

1: 88. Sources disagree as to how far inland the new foundation was, between one mile (Ab l-Fid) and five miles

(al-Dimashq), which indicates that these reports are not all copied from the same source.

122. Abu l-Fida 1840, 1: 247; 2,2: 26; Ibn Baa 1964, 1: 36; 1958, 1: 85. Ab l-Fid mentioned Beirut, but

only to quote from older sources, so his text gives no indication of its current size.

Carlson: The Geography of Islamization in Syria, 6001500

809

to Ab l-Fid, who participated in the capture of the latter.123 Between them, the formerly

important port of ayd was in the fourteenth century merely a small village, while further

south Qaysriyya, Arsf, and Asqaln were also ruined.124 Ab l-Fid seems to indicate that

the main beneficiaries of this coastal destruction were Gaza, which became the main port

for traders from the ijz, and the Cilician port of ys in the Armenian kingdom, which

became the preferred port for Christian merchants from Europe; between them, Yf was

the only port he identified as still active.125 The coastal areas, where the early Islamization

was most thoroughly reversed by the period of Crusader rule, were devastated rather than

reconverted by the conquerors from Cairo, who generally moved their governmental centers

inland.

Under Greek and Crusader rule, the coastline and northern Syria probably had a higher

proportion of Christians than other regions. After the Mamluk devastation of the coastline,

northern Syria remained the place where Christians were most frequently mentioned by

geographers. One interesting exception is al-Shawbak between Ammn and Ayla in southeastern Syria (today part of Jordan), which Ab l-Fid described as mostly inhabited by

Christians still in the fourteenth century.126 Otherwise, references to Christian populations in

Syria in the geographical works of the Mamluk period all refer to northern Syria. It is indicative in this regard that al-Dimashq describes the wildest party he knew of as Easter at am,

for which Christians would gather from all over northern Syria: im, Shayzar, Salamiyya,

Kafr b, Ab Qubays, Mayf, Maarrat al-Numn, Tzn, al-Bb, Buza, al-Fa, and

Aleppo.127 The annual festival at Dayr al-Frs outside Latakia likewise made an impression

on al-Dimashq, Ab l-Fid, and Ibn Baa.128 Urban Christian populations are indicated

at Anarss on the coast and in Damascus, where Ibn Baa recounted the combined prayer

procession of Jews, Muslims, and Christians in response to the arrival of the Black Death.129

It thus appears that most if not all of the urban centers of northern Syria had, or were plausibly reputed to have, Christian segments of the population into the fourteenth century.

Particular rural areas also became known for Christians, such as the Lake of the Christians north of Fmiya (ancient Apamea), whose eels were enjoyed by Christians, according

to al-Dimashq.130 On the other hand, Ibn Baa adapted Ibn Jubayrs description of the

villages in the Gha around Damascus, adding Friday mosques and markets to the earlier

travelers bathhouses as indicative of what most villages near Damascus possessed in the

fourteenth century.131 In rural areas, roads were important locations of non-Muslim visibility

to the Muslim population. One of the main roads from Iraq to Damascus passed through alSukhna, east of im, and when Ibn Baa passed that way in the mid-fourteenth century

123. Abu l-Fida 1840, 1: 243; 2,2: 20, 22; Ibn Baa 1964, 1: 35; 1958, 1: 83.

124. Abu l-Fida 1840, 1: 239, 249; 2,2: 17, 26; Ibn Baa 1964, 1: 34; 1958, 1: 81.

125. Abu l-Fida 1840, 1: 239, 249; 2,2: 16, 17, 27.

126. Yaqut al-Hamawi 1990, 3: 420; Abu l-Fida 1840, 1: 247; 2,2: 25.

127. Al-Dimashq 1866: 280; 1874: 408.

128. Al-Dimashq 1866: 209; 1874: 285; Abu l-Fida 1840, 1: 257; 2,2: 35; Ibn Baa 1964, 1: 49; 1958,

1: 115.

129. Al-Dimashq 1866: 2078; 1874: 283; Ibn Baa 1964, 1: 6061; 1958, 1: 144. A major textual variant in

the text of al-Dimashq questions whether the church and monastery are in Anarss or in Anafa, a coastal village.

The translator followed a Paris manuscript that ascribed them to the coastal village of Anafa northeast of Jubayl but

still placed another early monastery in Anarss.

130. Al-Dimashq 1866: 205; 1874: 279; Abu l-Fida 1840, 1: 41; 2,1: 51. Certain manuscripts of al-Dimashq

omit the reference to Christian fishermen, only referring to the eels.

131. Ibn Jubayr 1981: 224; 1952: 288; Ibn Baa 1964, 1: 63; 1958, 1: 148.

810

Journal of the American Oriental Society 135.4 (2015)

he described it as a fine town, most of whose inhabitants are Christian infidels.132 Closer

to Damascus, the town of Qra was described by Yqt as the first stopping point on the

straight road from im to Damascus, which is the main north-south road of central Syria.133

Yqt also indicated tersely that all of its people are Christians, while a generation earlier

Ibn Jubayr had said at greater length that the village belongs to Christians who dwell there

under treaty and in which there are no Muslims.134 In the fourteenth century Ab l-Fid

modified the description of Qras population to predominantly Christian, indicating that

this large town on a main road probably had its first Muslim inhabitants under Mamluk rule.135

Further north, the same author indicated the need to pass through the entirely Christian village of Yaghr near Antioch in order to reach the towns of Darbask and Baghrs, the former

of which had a mosque and minbar.136 As late as the middle of Mamluk rule, Muslim travelers in central and northern Syria might be forced to spend the night in villages with only a

small Muslim presence.

Following the Ottoman conquest of the early sixteenth century, tax registers survive that

permit a more detailed summary of the state of religious diversity in Syria. These records

indicate a small and almost exclusively urban Jewish population, comprising perhaps 2.6% of

the population of Aleppo in 924/1518, 6% of Damascus in ca. 950/1543, and around twenty

years earlier 11% of Sidon, 1.7% of Beirut, and 2% of Balabakk, northwest of Damascus.137