Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Impact 2.0 - The Production of Subjectivity, Expertise, and The Responsibility in A Necrogeographical World

Cargado por

Jay GasonTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Impact 2.0 - The Production of Subjectivity, Expertise, and The Responsibility in A Necrogeographical World

Cargado por

Jay GasonCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Impact 2.

0: The Production of Subjectivity,

Expertise, and Responsibility in a

Necrogeographical World

Lakhbir K. Jassal1

Institute of Geography,

School of GeoSciences,

The University of Edinburgh,

L.Jassal@sms.ed.ac.uk

Impact 2.0: The Transformation of the Postgraduate Subject

In the postgraduate world some are fearful or indifferent in thinking about the

impact of their research project. My own experience of impact was brought on by

my PhD research on governance and death. That research investigates matter out of

place (and on the move), particularly how what I refer to as the technique of

necropower and its opposite, the art(s) of not being governed, are manifest in

funeral and disposal practices amongst non-Abrahamic Indian and Chinese

residents in Great Britain.2 In all, the study traces the ways in which necropower

operates over the doubly abject (raced and culturally different dead), specifically

the corpse, the dead body and bodily remains in institutional and social contexts

structured by the logics of care, and the extent people will go to towards

challenging the clutches of the state.3 It was through this project I encountered both

a fearful and indifferent attitude towards this thing called impact.

Published under Creative Commons licence: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works

Disposal refers to the action or process of getting rid of something. The term has become contentious of late

however it remains a popular expression (coupled with scattering or dispersal) to describe the action involved

in sending-off the decomposing corpse/body and bodily remains in a manner that is both scientifically and

culturally safe.

3

The concept of necropower takes Michel Foucaults (1978, 2008) notion of biopower, usefully extended by

Nikolas Rose (1999), and applies it to the dead. To this end I also expand a concept of necropolitics identified

2

ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 2014, 13(1), 62-66

63

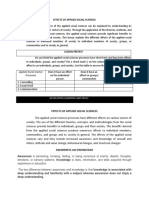

Death is not an altogether fashionable topic, although it is powerfully

impactful in and of itself. How to make necrogeography impactful, and for whom,

is something that concerns me. It is the kind of question that concerns all PhD

students. It is one of the norms which shapes postgraduate subjectivity, imposed

upon our bodies and souls (and our research) by those with vested interest in us and

our findings. Here I argue that impactful research operates with what Jane M.

Jacobs (2011, 412) refers to as irreconcilable grammars, and in many respects

impact is irreconcilable to the expectations and meaning of PhD research. I refer to

this type of outward facing effect as a governmental technology, a conceptual tool,

known as Impact 1.0. In 2011 Noel Castree described how the impact agenda

includes issues of public engagement and training undergraduates. This outward

facing Impact 1.0 ignores postgraduates who go out to take up external positions.

Indeed, I propose that the impact of postgraduate research should be framed by

different parameters, and calibrated by distinctive inward facing measures. I refer

to this alternative, as Impact 2.0 a conceptual tool that can facilitate an

understanding of how postgraduate subjectivity is shaped by diverse actors. Most

striking about this version is the assumption that training a PhD student is in itself

an impact. The criterion and parameters of Impact 2.0 include personal growth as

postgraduate students, the development of expertise in training, and the cultivation

of responsible citizens. Impact 2.0 calls for research assessment exercises to

recognize new forms of postgraduate subjectivity.

Postgraduate subjectivity is shaped by a variety of institutional academic

norms. We are governed experts-in-training in this sense. Many of us are in areas

that are not by their nature high profile. Take my own sub-field of research, that of

necrogeography; this was, to use a pun, a dying field in cultural (and political)

geography. My taking an interest in this area at the start of 2009 created an impact,

resuscitating necrogeography as a sub-disciplinary field and bringing to it questions

of governance. The cultural and political geographies of death, dying and disposal

warrant attention in order to survive in the discipline.4 So the very first act of

creating impact with my own research was to make the case for its relevance in the

discipline.

Postgraduate subjectivity and its impact potentials are further shaped by

institutions and organizations with whom we deal in the course of our research. In

my case, the Death Care Industry was a significant stakeholder with respect to the

funeral and disposal practices I was researching.5 These industry professionals

positioned themselves as experts yet they often viewed me as the expert in their

field. They looked to me for very practical information about how their services

by Mbembe (2003). My PhD study introduces necropower as a concept where state power is exercised not

through violence or explicit violation, but through the logics of care; whereas, counter-strategies are what I

called after Foucault (1997) and Scott (2009) the art of not being governed.

4

This was also pointed out by Kniffen (1967) and Kong (1999).

5

In recent times the funeral profession is euphemistically called the Death Care Industry (funeral parlours,

morticians, and commercial enterprises etc.).

Impact 2.0

64

might better meet the needs of their targeted clients. They wanted my research to

have impact on their global operations, however, there were limits on what I could

or could not do as a result of my position as a postgraduate research student. Thus,

the management of subjectivity is central to organisational cultures, such as the

Death Care Industry, which seeks to transform postgraduate subjectivity through a

variety of professional norms.

Research participants also shape postgraduate subjectivity. In my fieldwork

phase there was mutual reciprocity: my respondents helped me and they did so with

no explicit or immediate benefit to their lives. They took part in my research for a

range of indefinite returns, which included the belief that they were helping a

student move forward and simultaneously contributing to social change. They also

participated because they thought it would make a difference to how their own and

others practices and preferences of funeral and disposal would be recognized and

accommodated. For instance, one participant commented no matter how hard to

implement that practice [the right to funeral and disposal specific to all minority

and marginalised groups] its part of human rights. Yeah. If you make that part of

human rights policy, world policy, international laws that would help (Interview,

Chinese Community Member, 31/08/2010). For the diverse participants being a

research subject was an attempt to have an impact. For me, this faith and

expectation created additional responsibilities and worries that my research

circulates beyond the academy.

The impact effect is a technology of state institutional landscapes associated

with the academy and new cultures of auditing and accountability, as hinted in the

editorial introduction (Rogers et al., this issue). This impact agenda inevitably will

shape postgraduate subjectivity and research, but to what extent and by what moral

compass? Creating an impact-o-sphere depends a great deal on how we, as

postgraduates, transform ourselves through a variety of institutional and cultural

norms which steer our bodies and souls into productive subjects. I believe

postgraduates should strive for achieving impact, but for myself and the

participants in my research the question of what is impact? has many answers.

This multiplicity is part of the irreconcilable grammars of impact talk (Jacobs,

2011, 412). Impact 1.0, is in many ways an outward facing tool, which connects

academics with the aspirations of research assessment authorities. Impact 2.0 is

an inward facing tool which allows postgraduates to create space for user-friendly

connectivity. This includes recognising and being conscious of the fact that we are

governed by different vectors of power. So rather than just subscribing to the

demands of state authorities, Impact 2.0, is a conceptual tool that can help facilitate

a creative platform to connect with the lives of participants, organisations and

others.

This alternative 2.0, tool allows postgraduates to create impact through

creative engagement. In order to facilitate active engagement with those who

govern our research lives the ideas below offer a way to bring together practices of

self-management with the rendering of creativity.

ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, 2014, 13(1), 62-66

65

1) Being emotionally equipped

- self-reflection on the delicate networks that connect us to

different lives

- develop an inventive plan and have the flexibility to adapt it

based on diverse encounters to achieve your personal goals

2) Reset button

- continuously reinvent yourself through personal and politically

engaging practices. This will help one think differently about

who we are becoming as subjects governed by different vectors

of power

3) Cocktail recipe

- there are a range of ways to conduct [or improve] ourselves

(Rose, 1998, 159) through a mixture of self-governing techniques

that cultivate new forms of knowing

Although it is a great affirmation for people to know who you are by creating a

publication record, that in my view is not the sole point of the PhD journey. Instead

we need to be equipped to create our own impact-o-spheres and Impact 2.0 allows

us to do that.

Impact 2.0 is a conceptual tool that always measures personal growth as

postgraduate students, expertise in training, and responsiblization as citizens, active

in the lives of others. This is one way of navigating through the rich complexity of

expertise and responsibility shaped by a variety of disciplinary norms in an impact

driven age.

Acknowledgments

I wish to express sincere thanks to my supervisors Jane M. Jacobs, Elizabeth

Olson and Eric Laurier for their support and encouragement to think outside Impact

1.0.

References

Castree, Noel. 2011. Commentary the future of geography in English universities.

Geographical Journal 177, 294-299.

Foucault, Michel. 2008. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collge de

France, 1978-1979. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Foucault, Michel. 1997. The Politics of Truth. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Foucault, Michel. 1978. The History of Sexuality: An Introduction. London:

Penguin.

Jacobs, Jane M. 2011. Urban geographies I: still thinking cities relationally.

Progress in Human Geography 36, 412-422.

Impact 2.0

66

Kniffen, Fred B. 1967. Necrogeography in the United States. Geographical Review

57, 426-427.

Kong, Lily. 1999. Cemeteries and columbaria, memorials and mausoleums:

narrative and interpretation in the study of deathscapes in geography.

Australian Geographical Studies 37, 1-10.

Mbembe, Achille. 2003. Necropolitics. Public Culture 15, 11-40.

Rose, Nikolas. 1998. Inventing Our Selves: Psychology, Power, and Personhood.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rose, Nikolas. 1999. Governing the Soul: The Shaping of the Private Self. London:

Free Association Books.

Scott, James C. 2009. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of

Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

También podría gustarte

- Journey into Social Activism: Qualitative ApproachesDe EverandJourney into Social Activism: Qualitative ApproachesAún no hay calificaciones

- Taking Stock in The Interim: The Stuck, The Tired, and The ExhaustedDocumento5 páginasTaking Stock in The Interim: The Stuck, The Tired, and The ExhaustedPNirmalAún no hay calificaciones

- Content ServerDocumento15 páginasContent ServerBarbara muñozAún no hay calificaciones

- Sao Paulo, Salud PublicaDocumento12 páginasSao Paulo, Salud PublicaDocentes Ciudad CartagoAún no hay calificaciones

- The Importance of Research in The Advancement of Knowledge and SocietyDocumento3 páginasThe Importance of Research in The Advancement of Knowledge and SocietykkurtbrylleAún no hay calificaciones

- Jones 2018 Mediated Self CareDocumento22 páginasJones 2018 Mediated Self CareRodney Jones100% (1)

- Sciencedirect: An Empirical Study On Media Literacy From The Viewpoint of MediaDocumento7 páginasSciencedirect: An Empirical Study On Media Literacy From The Viewpoint of MediaHafid Muhammad RafdiAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Adaptation ThesisDocumento6 páginasSocial Adaptation ThesisAshley Hernandez100% (2)

- Chapter 15: Transdisciplinarity For Environmental LiteracyDocumento32 páginasChapter 15: Transdisciplinarity For Environmental LiteracyGloria OriggiAún no hay calificaciones

- Good Research Paper Topics Social WorkDocumento7 páginasGood Research Paper Topics Social Workgvyns594100% (1)

- Katz Busy Bodies 2000Documento18 páginasKatz Busy Bodies 2000Alexei70Aún no hay calificaciones

- Deborah Avant The Ethics of Engaged Scholarship in ADocumento22 páginasDeborah Avant The Ethics of Engaged Scholarship in AVespa SugioAún no hay calificaciones

- Disciplines and Ideas of Social SciencesDocumento5 páginasDisciplines and Ideas of Social SciencesAlthea DimaculanganAún no hay calificaciones

- Structural FuncionalismDocumento5 páginasStructural Funcionalismzerihun ayalewAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Work Research Paper TopicsDocumento5 páginasSocial Work Research Paper Topicsaflbojhoa100% (1)

- Scientific Research and Social ResponsibilityDocumento11 páginasScientific Research and Social ResponsibilityTesis LabAún no hay calificaciones

- Deconstructing DisseminationDocumento29 páginasDeconstructing DisseminationJeremiahOmwoyoAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Work Research Paper FormatDocumento7 páginasSocial Work Research Paper Formatxdhuvjrif100% (1)

- Theory-Practice Gap in Foresight FieldDocumento12 páginasTheory-Practice Gap in Foresight FieldRajesh KalarivayilAún no hay calificaciones

- Changing Social Relations of Disability ResearchDocumento15 páginasChanging Social Relations of Disability ResearchDenisson Gonçalves ChavesAún no hay calificaciones

- Implications of Social Constructionism To Counseling and Social Work PracticeDocumento26 páginasImplications of Social Constructionism To Counseling and Social Work PracticeWahyuYogaaAún no hay calificaciones

- Blackmann, L. AffectDocumento23 páginasBlackmann, L. Affectpriscila_cedilloAún no hay calificaciones

- Week 004 - Contextual Research in Daily Life 1 - Qualitative Research and Its Importance in Daily LifeDocumento6 páginasWeek 004 - Contextual Research in Daily Life 1 - Qualitative Research and Its Importance in Daily LifeJoana MarieAún no hay calificaciones

- Research paradigms: ontology, epistemology and methodologyDocumento27 páginasResearch paradigms: ontology, epistemology and methodologyHany A AzizAún no hay calificaciones

- Importance of Qualitative Research Across FieldsDocumento20 páginasImportance of Qualitative Research Across FieldsOmairah S. MalawiAún no hay calificaciones

- Human AspirationDocumento21 páginasHuman Aspirationchikakai11Aún no hay calificaciones

- Ali Yu Ontology Paper 9Documento27 páginasAli Yu Ontology Paper 9JV BernAún no hay calificaciones

- Effects of Applied Social SciencesDocumento6 páginasEffects of Applied Social SciencesJhona Rivo Limon75% (4)

- Ciencia y AccionDocumento18 páginasCiencia y AccionLuis Jesus Malaver GonzalezAún no hay calificaciones

- 154-170 DopieralaDocumento17 páginas154-170 DopieralathuydunghotranAún no hay calificaciones

- Functionalist ThesisDocumento4 páginasFunctionalist Thesisggzgpeikd100% (2)

- Social Worker Research PaperDocumento8 páginasSocial Worker Research Paperqirnptbnd100% (1)

- Sociology Lecture NotesDocumento5 páginasSociology Lecture Notesc6pbzf4mdrAún no hay calificaciones

- Sociology Senior Thesis IdeasDocumento4 páginasSociology Senior Thesis Ideasmarcygilmannorman100% (2)

- STS 1 - Module 2 ReviewerDocumento4 páginasSTS 1 - Module 2 ReviewerPatrick Angelo Abalos SorianoAún no hay calificaciones

- Gauttier (2019) ExosenseDocumento24 páginasGauttier (2019) ExosenseAndré AlexandreAún no hay calificaciones

- A Reflexive Look at Reflexivity in Environmental SociologyDocumento12 páginasA Reflexive Look at Reflexivity in Environmental SociologynikitaAún no hay calificaciones

- Sample Research Paper Social WorkDocumento7 páginasSample Research Paper Social Worklrqylwznd100% (1)

- Management Research After Modernism, Andrew M. PettigrewDocumento10 páginasManagement Research After Modernism, Andrew M. PettigrewAngelo Brigato ÉstherAún no hay calificaciones

- Assignment 1: Muhammad Ali AsifDocumento4 páginasAssignment 1: Muhammad Ali AsifAli PuriAún no hay calificaciones

- Artikel 1Documento16 páginasArtikel 1feren ditaAún no hay calificaciones

- A Critical Theory of Medical DiscourseDocumento21 páginasA Critical Theory of Medical DiscourseMarita RodriguezAún no hay calificaciones

- Understanding The Socialized Body-Libre PDFDocumento16 páginasUnderstanding The Socialized Body-Libre PDFWishUpikAún no hay calificaciones

- The Systemic Dimension of GlobalizationDocumento290 páginasThe Systemic Dimension of Globalizationnithin_v90Aún no hay calificaciones

- Community Participation Literature ReviewDocumento4 páginasCommunity Participation Literature Reviewhpdqjkwgf100% (1)

- Problems of Social Research in NigeriaDocumento8 páginasProblems of Social Research in Nigeriacephaspeter123Aún no hay calificaciones

- E) Engagement - We Don't Exclude The K But Policy Relevance Is Key To Change Campbell, 02Documento8 páginasE) Engagement - We Don't Exclude The K But Policy Relevance Is Key To Change Campbell, 02yesman234123Aún no hay calificaciones

- Nisbet-What's Next For Science CommunicationDocumento13 páginasNisbet-What's Next For Science Communicationstefan.stonkaAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Methods NotesDocumento122 páginasResearch Methods NotesSunguti KevAún no hay calificaciones

- A Dimensional Model For Cultural BehaviorDocumento24 páginasA Dimensional Model For Cultural BehaviorNihalGawwadAún no hay calificaciones

- Jalpp00507 Jones F (SS) 1Documento38 páginasJalpp00507 Jones F (SS) 1Rodney JonesAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Paper Topics For Social WorkDocumento7 páginasResearch Paper Topics For Social Worktijenekav1j3100% (1)

- Challenge of Power Sharing ArticleDocumento8 páginasChallenge of Power Sharing ArticleVelaniAún no hay calificaciones

- How Empowering Is Social Innovation? Identifying Barriers To Participation in Community Driven InnovationDocumento17 páginasHow Empowering Is Social Innovation? Identifying Barriers To Participation in Community Driven InnovationNesta100% (6)

- The Future of Public Organizations: Burhan Aykac, Hatice MetinDocumento5 páginasThe Future of Public Organizations: Burhan Aykac, Hatice MetinLy DLunaAún no hay calificaciones

- Research Concepts, Nature, and Scope of CommunicationDocumento13 páginasResearch Concepts, Nature, and Scope of CommunicationNiraj kumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Gerontology As Public Sociology in ActionDocumento18 páginasSocial Gerontology As Public Sociology in ActionVARSHA MOHANAún no hay calificaciones

- Mattaini - 2019 - Out of The Lab Shaping An Ecological and Constructional Cultural Systems ScienceDocumento19 páginasMattaini - 2019 - Out of The Lab Shaping An Ecological and Constructional Cultural Systems ScienceCamila Oliveira Souza PROFESSORAún no hay calificaciones

- Haas - Pragmatic ConstructivismDocumento30 páginasHaas - Pragmatic ConstructivismBejmanjinAún no hay calificaciones

- Weld Re-5j School Calendar - 2021-2022Documento1 páginaWeld Re-5j School Calendar - 2021-2022api-523000881Aún no hay calificaciones

- IJSO Previous 10 Year PapersDocumento155 páginasIJSO Previous 10 Year PapersTanmoy GuptaAún no hay calificaciones

- PHD RegulationsDocumento17 páginasPHD RegulationsFrances DoloresAún no hay calificaciones

- BZU Multan Job Vacancies for Assistant Professors and LecturersDocumento15 páginasBZU Multan Job Vacancies for Assistant Professors and LecturersSaleem MirraniAún no hay calificaciones

- Sample Personal StatementDocumento1 páginaSample Personal StatementNimantha LakshanAún no hay calificaciones

- Anna Green ReviewDocumento5 páginasAnna Green ReviewMiguel Angel ChchamavAún no hay calificaciones

- Mahatma Gandhi University fee details for UG, PG, diploma coursesDocumento2 páginasMahatma Gandhi University fee details for UG, PG, diploma coursesSonu SinghAún no hay calificaciones

- All About ClatDocumento21 páginasAll About ClatShantamAún no hay calificaciones

- Understanding Culture, Society and PoliticsDocumento28 páginasUnderstanding Culture, Society and PoliticsJhaspher CasillanAún no hay calificaciones

- YVUCET 2019 ProspectusDocumento12 páginasYVUCET 2019 ProspectusprembiharisaranAún no hay calificaciones

- Fresno PortfolioDocumento3 páginasFresno Portfolioapi-349060944Aún no hay calificaciones

- BA (H) Political ScienceDocumento3 páginasBA (H) Political SciencerisameAún no hay calificaciones

- 9 Beryllium Academic Honesty ACRDocumento4 páginas9 Beryllium Academic Honesty ACRJerick SubadAún no hay calificaciones

- DR B.R.Ambedkar Open Ijnryers : Recognition To ProgrammesDocumento127 páginasDR B.R.Ambedkar Open Ijnryers : Recognition To ProgrammesmanivithAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Science CH 1 NotesDocumento6 páginasSocial Science CH 1 NotesHayley BarrettAún no hay calificaciones

- And Dissertations: Ffiffi - EstepafueaDocumento6 páginasAnd Dissertations: Ffiffi - EstepafueaCornelia FeraruAún no hay calificaciones

- Uom CoursesDocumento4 páginasUom Coursesdeepti_555Aún no hay calificaciones

- Global Experience Education: GeophysicistDocumento1 páginaGlobal Experience Education: GeophysicistgeoneroAún no hay calificaciones

- Academic CalendarDocumento1 páginaAcademic CalendarSudesh NairAún no hay calificaciones

- NHAYSLADITADocumento9 páginasNHAYSLADITAMakaldsaMacolJr.Aún no hay calificaciones

- Master of Arts in Education (MAED) degreeDocumento18 páginasMaster of Arts in Education (MAED) degreeBraiden ZachAún no hay calificaciones

- A Unit 1st Merit List Male Female JU 2019-20 (Updated)Documento12 páginasA Unit 1st Merit List Male Female JU 2019-20 (Updated)rifat azimAún no hay calificaciones

- Philosophy & Social Sciences RiseDocumento4 páginasPhilosophy & Social Sciences RiseDannah Gutierrez100% (1)

- Campus Map EnglishDocumento2 páginasCampus Map Englishjunaidtps1Aún no hay calificaciones

- New College News 2006Documento2 páginasNew College News 2006toobaziAún no hay calificaciones

- Downing College Cambridge Magazine 2012Documento134 páginasDowning College Cambridge Magazine 2012Fuzzy_Wood_PersonAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is Political Science All AboutDocumento3 páginasWhat Is Political Science All Aboutmingo quixoteAún no hay calificaciones

- (H) Result May2015Documento223 páginas(H) Result May2015gurjeetkaur1991Aún no hay calificaciones

- Academic Calendar 2013Documento3 páginasAcademic Calendar 2013tojinboAún no hay calificaciones

- 98th Annual Convocation Gold Medal P GDocumento161 páginas98th Annual Convocation Gold Medal P GMohan KumarAún no hay calificaciones