Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Cultures Matter - A Review Article of Books by Harrison and Huntin

Cargado por

xrosspointTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Cultures Matter - A Review Article of Books by Harrison and Huntin

Cargado por

xrosspointCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture

ISSN 1481-4374

Purdue University Press Purdue University

Volume 5 (2003) Issue 1

Article 7

Cultur

ultures

es M

Maatttteer: A R

Rev

eview

iew A

Arrticle of BBoook

okss bbyy H

Haarrison aand

nd H

Hun

unttin

inggton

on,, SSeges

egesvvr y, aand

nd BBrreck

eckeenr

nrid

idge

ge,, PPol

ollo

lock

ck,, BBhhabh

bhaa,

and C

Chhakr

akraabarty

Williliaam H. Thor

Thornnton

National Cheng Kung University

Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb

Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons

Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and

distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business,

technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences.

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the

humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and

the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the

Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index

(Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the

International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is

affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact:

<clcweb@purdue.edu>

Recommended Citation

Thornton, William H. "Cultures Matter: A Review Article of Books by Harrison and Huntington, Segesvry, and Breckenridge,

Pollock, Bhabha, and Chakrabarty." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 5.1 (2003): <http://dx.doi.org/10.7771/

1481-4374.1184>

This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field.

The above text, published by Purdue University Press Purdue University, has been downloaded 3475 times as of 06/01/15. Note:

the download counts of the journal's material are since Issue 9.1 (March 2007), since the journal's format in pdf (instead of in html

1999-2007).

UNIVERSITY PRESS <http://www.thepress.purdue.edu>

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture

ISSN 1481-4374 <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb>

Purdue University Press Purdue University

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the

humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative

literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." In addition to the

publication of articles, the journal publishes review articles of scholarly books and publishes research material in its

Library Series. Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and

Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities

Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <clcweb@purdue.edu>

Volume 5 Issue 1 (March 2003) Book Review Article

William H. Thornton,

"Cultures Matter: A Review Article of Books by Harrison and Huntington, Segesvry, and

Breckenridge, Pollock, Bhabha, and Chakrabarty"

<http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol5/iss1/7>

Contents of CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 5.1 (2003)

<http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol5/iss1>

William H. Thornton, Cultures Matter: A Book Review Article

page 2 of 4

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 5.1 (2003): <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol5/iss1/7>

William H. Thornton

Cultures Matter: A Review Article of Books by Harrison and Huntington, Segesvry, and

Breckenridge, Pollock, Bhabha, and Chakrabarty

This book review article is about new work published by Lawrence E. Harrison and Samuel P.

Huntington, eds., Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress (New York: Basic Books, 2000),

Victor Segesvary, Dialogue of Civilizations: An Introduction to Civilizational Analysis (Lanham:

University Press of America, 2000), and Carol A. Breckenridge, Sheldon Pollock, Homi Bhabha, and

Dipesh Chakrabarty, eds., Cosmopolitanism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002).

In many respects Culture Matters was dated on the day it went to press. Its unifying concern -- the

salient role of culture in economic development and underdevelopment -- heavily favors one cultural

model while treating all others as developmental impediments. To say that "culture matters,"

therefore, is not to say that "cultures matter." For roughly a decade, from the mid 1980s to the mid

1990s, that singular usage held sway in world affairs, drawing support from the ongoing "Asian

miracle," post-Cold War globalism, the American New Economy, and the Right turn of Latin America.

Unfortunately for Culture Matters, history did not end on that triumphal note. After the Asian Crash,

the collapse of the U.S. market, the Enron debacle, and the rebound of Left populism in Latin America,

Culture Matters finds itself marching on an empty parade ground. It entirely misses, moreover, the

most pressing question of them all: the cultural provenance of jihadic terrorism. It turns out that

Culture Matters' principal editor, Lawrence Harrison, is something of a one trick pony, not to mention

a one-culture culturalist. Since 1985 he has been mired in a rearguard defense of his neomodernist

classic, Underdevelopment is a State of Mind: The Latin American Case. All of Culture Matters'

contributors, even those few who are out of step in Harrison's parade, are forced to march to its music.

From this perspective East Asia's economic success and Latin America's failure are twin lessons in a

cultural morality tale whereby the capitalist West is set up as the obligatory model for global

emulation. Harrison et al. bear glad tidings for underdeveloped countries: salvation is close at hand.

All it requires is the total forfeiture of your cultural identity and every trace of resistance, especially

dependency theory.

Strangely, for a book published in 2000, this developmental "state of mind" takes little account of

the Asian Crash of 1997-98. Although three articles are nominally assigned to the subject, only Lucian

Pye is bold enough to say the emperor never had any clothes: the "Asian miracle" is and always has

been a tendentious myth. Stranger still, the famous cultural admonition of Culture Matters' other

editor, Samuel Huntington, is kept on the bench throughout the game. This is most unfortunate, for

Huntingtons concept of "civilizational clash" has been at the cutting edge of debate after 9/11.

Regretfully Culture Matters suits him up for promotional purposes only (see Huntington's confession to

this effect xv). Henderson's oppositional selections are equally duplicitous. Although his main target is

the Left, none of Culture Matters' dissenting voices are actually on the Left. One suspects that Richard

Schweder's fleeting complaint about Harrison's developmentalism got in by accident. True to his

anthropological calling, Schweder was primarily interested in defending cultural difference against the

ravages of Harrison's cultural unilateralism. This was no doubt expected, but in the heat of argument

Schweder struck at least a glancing blow for the Left.

Several contributors with Third World backgrounds took umbrage at Schweder's charge that they

had been used to stack the deck with pseudo-insiders. But the patent fact is they were put there to

confirm Henderson's thesis on "native grounds." A more forthright title for this book, therefore, would

have been Western Capitalist Culture Matters. Not surprisingly the contrary voices in Culture Matters

make for the best reading. In addition to Schweder and the inimitable Pye, a different slant on cultural

matters is provided by Jeoffrey Sachs, Jared Diamond, and Nathan Glazer. While these antithetic or at

least qualifying chapters are a welcome diversion, Culture Matters keeps its thematic house in order.

William H. Thornton, Cultures Matter: A Book Review Article

page 3 of 4

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 5.1 (2003): <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol5/iss1/7>

It fails, however, in its larger purpose of proving the undiminished relevance of Henderson's Reagan

era thesis for the twenty-first century. That is because Culture Matters lacks any compelling sense of

how much things have changed since 1985. There is no serious attention, for example, to the cultural

maelstrom unleashed by the end of the Cold War. Instead we get a full blast of New Economy hubris.

Nonetheless Culture Matters should be required reading in any cultural studies program -- not for the

light it sheds on global development, but as an icon of Roaring 1990s economism and Washington

consensus globalism.

A balanced if somewhat ethereal corrective is available in Victor Segesvary's "civilizational

pluralism." Here Harrison's Culture Matters gives way, in effect, to Cultures Matter. For Sevesvary

cultures are rooted in existence and thus are incommensurable. But far from seeing cultures as

monadic, he considers intercultural dialogue all the more imperative in the face of globalization. The

worst case scenario from this pluralist vantage is the kind of monocultural imperialism that Harrison

advances in the name of development. In Dialogue of Cultures, Segesvary addresses the core problem

that Henderson manages to evade: the cultural homogenization that globalism enforces. This

civilizational onslaught has thrown non-capitalist cultures into a struggle (the proper Koranic meaning

of contemporary jihad) for their very survival. The Moslem world is especially prone to this crisis

because religion is such an integral part of daily life under Islam. Secularization, even on the most

benign terms, becomes threatful to this ethos; and today's globalization is anything but benign. The

problem is compounded by the fact that Western secularism is itself a sacralized ideology. Resting as

it does on purely material modes of social interaction, globalization cannot answer questions of

ultimate concern. Religious fundamentalism, Islamic and otherwise, responds to this threat by

retreating even farther into a lair of security and certainty. This is its answer to globalization's myth of

the market and the prima facie value (as opposed to virtue) of consumerist culture. The irony is that

fundamentalism, in rejecting the cultural revolution that globalization requires, foments a reactionary

cultural revolution that is anti-modern but hardly traditional. Segesvary does not, however, see Islam

as inherently reactionary. He includes in his appendix the 1999 "Tehran Declaration on Dialogue

Among Civilizations," which calls for human diversity, tolerance, and mutual respect among cultures.

Such civil (as opposed to secularist) Islam is only "anti-Western" insofar as it rejects all cultural

domination, whether from Washington or Al Qaeda. It was in this spirit that Iran's president Khatami,

at the Eighth Islamic Summit, endorsed the plan for a UN Year of Dialogue Among

Civilizations. Paradoxically, that year was to be 2001. History, one could say, is what happens while

we make other plans.

By granting that their topic is not "a known entity existing in the world," but "something awaiting

realization" (1), the editors of Cosmopolitanism inadvertently cast their culture model as one more

utopian plan awaiting history's axe. Still, this is a big improvement over past cosmopolitanisms, which

as Ackbar Abbas notes were merely extensions of First World culture (210). That is to say they

marched in the same modernist parade that Harrison would have us revive. By contrast, postmodern

cosmopolitanism, as advanced by Ulf Hannerz, undertakes to engage the cultural "other" rather than

expunge it. In the spirit of other compradorist projects -- the "Third Way," "glocalization,"

"hybridization," etc. -- today's cosmopolitans seek a place for the "other" within rather than against

globalization. This retreat from direct resistance does not, in Sheldon Pollock's view, involve simple

"mongrelization" or mlange. Rather it counters cultural domination by way of strategic appropriation

(47). That is enough, in Dipesh Chakrabarty's opinion, to get us past the morass of totalistic

universalism versus absolute relativism (82), which would be no small accomplishment.

In a richly nuanced exposition of Bombay's cultural resilience, Arjun Appaduri illustrates how the

local can make its mark in a globalized world. Mamadou Diouf further explores this question in the

context of his study of a Senegalege religious group, the Murid Brotherhood. He concludes that such

remodeled traditions hold their own against the homogenizing forces of modernization and now

globalization (114). So too, in another Sengalese study, Tiki Biaya concludes that traditional African

William H. Thornton, Cultures Matter: A Book Review Article

page 4 of 4

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 5.1 (2003): <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb/vol5/iss1/7>

values are alive and well in local Islamic culture (154). In one way or another, all the chapters in

Cosmopolitanism support the proposition that distinct cultures -- locally rooted but not static or

territorially bounded -- still thrive in our globalized world. That is good news for the future of cultural

anthropology, and cultural studies generally, but it sheds little light on the cultural enmity that

erupted in the 1990s and culminated in 9/11. For all their profound differences, the three cultural

models under examination in this review share one dubious feature: a happy ending. They all tell us,

in effect, that the cultural inroads of globalization are manageable. Since cultural imperialism is no

real threat, radical action is not required, and indeed would be counterproductive.

Such complacence is the cultural complement of economic TINAism -- the view that "there is no

alternative" to current globalization. We are given to believe that while "culture matters," cultural

imperialism does not; for the impositions of the global can easily be foiled by the local. This good news

not only enjoins us to forget Seattle, but to rule out cultural aggression as a motive for global

terrorism. Thanks in part to this blackout, the tragic dialectic that Benjamin Barber adumbrated in

Jihad vs. McWorld (1995) was left to fester unattended for another six years. Suffice it to say that the

cultural studies establishment was caught entirely off guard on 9/11. Along with the general public,

but with far less excuse, these advocates of shore-to-shore cultural confluence found themselves

asking, "Why?" They had long neglected to ask if the so-called underdeveloped world, and the Muslim

world in particular, wanted any part of their vaunted cultural hybridity. Like the editors of Culture

Matters and Cosmopolitanism, they brought in a host of putative "insiders" -- well educated, well

traveled, well funded, yet "Third World" -- to assure themselves that residents of the periphery were

relishing the cultural choices that globalization affords. It may well be that cultural appropriation is the

closest thing to real resistance that most on the global periphery can muster. But that is nothing to

celebrate. No one thought to ask these "peripherals" if they might prefer a less placid form of

resistance -- perhaps something more like 9/11. That oversight has consequences not only for foreign

affairs but for the question of how "cultures matter." Segesvary's recourse to "civilizational pluralism"

has a nice ring, but it ultimately amounts to star gazing on the deck of the Titanic. It never gets

around to advising the captain to reduce his speed through the ice fields. If 9/11 does not get that

point across, nothing will.

Reviewer's profile: William H. Thornton teaches literary and cultural theory at National Cheng Kung University,

Tainan, Taiwan. He is the author of Cultural Prosaics: The Second Postmodern Turn (1998) and Fire on the Rim:

The Cultural Dynamics of East/West Power Politics (2002) as well as several dozen journal articles in literary and

cultural studies and on political culture. Thornton has published "A Postmodern Solzhenitsyn?" in CLCWeb 1.3

(1999) and "Analyzing East/West Power Politics in Comparative Cultural Studies" in CLCWeb: Comparative

Literature and Culture 2.3 (2000). E-mail: <william.thornto@msa.hinet.net>.

También podría gustarte

- Globalization and IdentyDocumento4 páginasGlobalization and IdentyxrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Plan Melbourne May 2014Documento220 páginasPlan Melbourne May 2014xrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- How To Make A City GreatDocumento44 páginasHow To Make A City GreatSyed Shah Ali HussainiAún no hay calificaciones

- Mind - Society and BehaviourDocumento236 páginasMind - Society and BehaviourxrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Integrated Governance Follow Up Report DraftDocumento23 páginasIntegrated Governance Follow Up Report DraftxrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Shanghai MasterplanDocumento2 páginasShanghai MasterplanxrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Metropolitanhierarchy DefDocumento11 páginasMetropolitanhierarchy DefxrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Regional Growth Strategy - Final Report Sept 21 2010Documento49 páginasRegional Growth Strategy - Final Report Sept 21 2010xrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Regional Growth Strategy - Final Report Sept 21 2010Documento49 páginasRegional Growth Strategy - Final Report Sept 21 2010xrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- ScenarioanalysisDocumento26 páginasScenarioanalysisxrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Regionale Sustainable StrategyDocumento124 páginasRegionale Sustainable StrategyxrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Asian Green City IndexDocumento63 páginasAsian Green City IndexregAún no hay calificaciones

- Scenario Planning Building Scenarios at Roland Berger 20130826Documento33 páginasScenario Planning Building Scenarios at Roland Berger 20130826xrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Corporative LearningDocumento18 páginasCorporative LearningxrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Casey FDN - Theory of Change Manual 2004Documento49 páginasCasey FDN - Theory of Change Manual 2004_sdpAún no hay calificaciones

- History Dengue Outbreaks Americas 2012Documento10 páginasHistory Dengue Outbreaks Americas 2012xrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Environment and Urbanization 2014 Satterthwaite 3 10Documento9 páginasEnvironment and Urbanization 2014 Satterthwaite 3 10xrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Urbanisme - Conferentie Leuven 2009Documento544 páginasUrbanisme - Conferentie Leuven 2009xrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Corporatief LerenDocumento20 páginasCorporatief LerenxrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Human Development Report 2013Documento216 páginasHuman Development Report 2013Kamala Kanta DashAún no hay calificaciones

- Adult Learning Theories and PracticesDocumento8 páginasAdult Learning Theories and PracticesModini BandusenaAún no hay calificaciones

- Knowledge Is Power: Measuring The Competitiveness of Global SydneyDocumento12 páginasKnowledge Is Power: Measuring The Competitiveness of Global SydneyxrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Liveability Ranking and Overview PDFDocumento9 páginasLiveability Ranking and Overview PDFxrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Global Power City Index 2011 PDFDocumento20 páginasGlobal Power City Index 2011 PDFxrosspoint100% (1)

- Measuring City Competitiveness Report May 2013 3 PDFDocumento17 páginasMeasuring City Competitiveness Report May 2013 3 PDFxrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- MGI Urban World Mapping Economic Power of Cities Full Report PDFDocumento62 páginasMGI Urban World Mapping Economic Power of Cities Full Report PDFxrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- Ukeo Largest City Economies in The World Sectioniii PDFDocumento15 páginasUkeo Largest City Economies in The World Sectioniii PDFxrosspointAún no hay calificaciones

- World Happiness Report 2013Documento156 páginasWorld Happiness Report 2013sofiabloemAún no hay calificaciones

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2102)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- HR LAW List of CasesDocumento2 páginasHR LAW List of Caseslalisa lalisaAún no hay calificaciones

- Tamil Nadu District Limits Act, 1865Documento2 páginasTamil Nadu District Limits Act, 1865Latest Laws TeamAún no hay calificaciones

- Macalintal Vs PET - DigestDocumento1 páginaMacalintal Vs PET - DigestKristell FerrerAún no hay calificaciones

- Working Paper For The ResolutionDocumento3 páginasWorking Paper For The ResolutionAnurag SahAún no hay calificaciones

- Undoing Monogamy by Angela WilleyDocumento38 páginasUndoing Monogamy by Angela WilleyDuke University Press100% (2)

- Rethinking Identity in The Age of Globalization - A Transcultural PerspectiveDocumento9 páginasRethinking Identity in The Age of Globalization - A Transcultural PerspectiveGustavo Menezes VieiraAún no hay calificaciones

- John Locke Gen GoDocumento11 páginasJohn Locke Gen GoragusakaAún no hay calificaciones

- Young 1996Documento19 páginasYoung 1996Thiago SartiAún no hay calificaciones

- UTTAR PRADESH UP PCS UPPSC Prelims Exam 2009 General Studies Solved PaperDocumento24 páginasUTTAR PRADESH UP PCS UPPSC Prelims Exam 2009 General Studies Solved PaperRishi Kant SharmaAún no hay calificaciones

- The LetterDocumento10 páginasThe Letterderrick marfoAún no hay calificaciones

- 201438755Documento74 páginas201438755The Myanmar TimesAún no hay calificaciones

- JOURNAL ARTICLE, VOLUME, 1 (1) - 24, MARCH, 2019, Author: Onesmo Daniel Mkepule. Title: Tanu'S Supremacy and Patriotism of Mwalimu J.K NyerereDocumento22 páginasJOURNAL ARTICLE, VOLUME, 1 (1) - 24, MARCH, 2019, Author: Onesmo Daniel Mkepule. Title: Tanu'S Supremacy and Patriotism of Mwalimu J.K NyerereAnonymous wApEsk4Aún no hay calificaciones

- Should The Philippines Turn Parliamentary by Butch AbadDocumento19 páginasShould The Philippines Turn Parliamentary by Butch AbadBlogWatch100% (1)

- 5 6131838952102954994Documento32 páginas5 6131838952102954994raj chinnaAún no hay calificaciones

- (Bassiouney,-Reem) - Language-And-Identity-In-Modern Egypt PDFDocumento418 páginas(Bassiouney,-Reem) - Language-And-Identity-In-Modern Egypt PDFmarija999614350% (2)

- List Del 1 1 enDocumento108 páginasList Del 1 1 enElena PutregaiAún no hay calificaciones

- Issue 14Documento4 páginasIssue 14dzaja15Aún no hay calificaciones

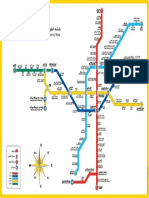

- Tehran Urban & Suburban Railway (Metro) Map: TajrishDocumento1 páginaTehran Urban & Suburban Railway (Metro) Map: TajrishthrashmetalerAún no hay calificaciones

- Atal Bihari Horo by KN RaoDocumento13 páginasAtal Bihari Horo by KN RaoRishu Sanam GargAún no hay calificaciones

- CollaborationDocumento16 páginasCollaborationDarleneAún no hay calificaciones

- Wahhabi' Influences, Salafi Responses: Shaikh Mahmud Shukri and The Iraqi Salafi Movement, 1745-19301Documento22 páginasWahhabi' Influences, Salafi Responses: Shaikh Mahmud Shukri and The Iraqi Salafi Movement, 1745-19301Zhang Hengchao100% (1)

- Final-Final-Thesis 2Documento74 páginasFinal-Final-Thesis 2Daniel DimanahanAún no hay calificaciones

- Legal Forms Legal Memorandum: Atty. Daniel LisingDocumento7 páginasLegal Forms Legal Memorandum: Atty. Daniel LisingAlyssa MarañoAún no hay calificaciones

- Bastiat CaucusDocumento2 páginasBastiat CaucusRob PortAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 1. Statutes: A. in GeneralDocumento18 páginasChapter 1. Statutes: A. in GeneralMarco RamonAún no hay calificaciones

- Domestic Violence Act Misused - Centre - The HinduDocumento8 páginasDomestic Violence Act Misused - Centre - The Hinduqtronix1979Aún no hay calificaciones

- Spousal Collection - Part 2Documento248 páginasSpousal Collection - Part 2Queer OntarioAún no hay calificaciones

- Parks v. Province of TarlacDocumento1 páginaParks v. Province of TarlaccarmelafojasAún no hay calificaciones

- Buchi Emecheta BiographyDocumento20 páginasBuchi Emecheta Biographyritombharali100% (1)

- Case Studies Report Final 2013Documento135 páginasCase Studies Report Final 2013wlceatviuAún no hay calificaciones