Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Malnutrition and Infection

Cargado por

sobanDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Malnutrition and Infection

Cargado por

sobanCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

DEFENCE AGAINST INFECTION

normally ingested together in food, macronutrient deficiency is

an indicator of likely micronutrient deficiency. The converse may

not be true, however; specific micronutrient deficiencies may arise

despite an adequate proteinenergy intake.

Malnutrition may be defined in several ways, of which weight

loss is the most common. Weight loss may be dynamic (I have lost

6 kg over 2 months), relative (I am 5 kg less than my usual body

weight) or static (I am badly underweight). Static measures are

best related to an absolute scale, but weight must be normalized for

body size before a meaningful comparison may be made, otherwise

small and wasted may be confused. In adults, normalization

is best achieved using BMI (span may be used if height is not

available), which has a normal range of 2025 kg/m2. Degrees of

malnutrition defined by BMI are shown in Figure 2. In children,

weight-for-height/length or height/length-for-age are alternative

indices.

Malnutrition and infection

Derek Macallan

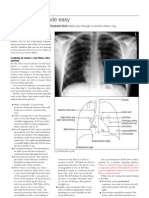

There are two aspects to the interaction between malnutrition and

infection (Figure 1):

the effect of nutritional state on susceptibility to and severity

of infective episodes

the effect of infection on metabolism and nutritional state.

Malnutrition is a major problem worldwide. Children are most

affected (see MEDICINE 31:4, 18), though this contribution focuses

on adults. The extent of malnutrition in hospitalized adult patients

in Western countries is largely unappreciated. In one study, about

40% of a sample of UK hospital patients were undernourished

on admission (body mass index, BMI < 20 kg/m2) and most

patients lost further weight during their stay (mean change

5.4%); weight loss was greatest in those who were initially most

undernourished.

Assessment of nutritional state

Assessment of nutritional state is easily neglected in the acute

medical setting. Appearances may be misleading, particularly

when oedema is present. For example, cushingoid patients may

have marked depletion of lean body tissue but not appear malnourished. Other parameters may be helpful in addition to weight

and BMI.

Anthropometric parameters include skin-fold thickness at

defined sites, muscle circumference and waist:hip ratio. Mid-upper

arm circumference (MUAC) is a useful indicator of malnutrition

that can be used in ill patients (normal MUAC > 23 cm in males,

> 22 cm in females).

Bioelectrical impedance analysis is an easy-to-use bedside test

that predicts the mass of different body compartments from resistance and reactance to the passage of a small alternating electric

current.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and CT may be used to

measure fat and lean compartments, but are essentially research

tools.

Malnutrition

Defining malnutrition

The term malnutrition refers primarily to deficiency of macronutrients (carbohydrate, protein and lipid), which manifests as

wasting, though it may also refer to specific deficiencies of vitamins

or trace elements. Because macronutrients and micronutrients are

Assessment in children: the most sensitive marker of nutritional

deprivation in children is failure to grow; this is because children

initially conserve energy and protein by slowing growth rather

than using reserves. Specific measures include weight-for-age and

Derek Macallan is Reader and Honorary Consultant in Infectious Diseases

at St Georges Hospital Medical School, London, UK.

Malnutrition and infection

Compromised barrier defences

Impaired cellular immunity

Impaired humoral immunity

Increased risk

Increased severity

Malnutrition

Infection

Negative energy balance

Anorexia

Increased

metabolic rate

Protein catabolism

Acute-phase response

MEDICINE 33:3

14

2005 The Medicine Publishing Company Ltd

DEFENCE AGAINST INFECTION

height-for-age. Severe proteinenergy malnutrition may result in

kwashiorkor with marked oedema.

Nutritional deficiency may turn a relatively mild illness into

a severe disease. In many developing countries, for example,

vitamin A deficiency dramatically increases the morbidity and

mortality caused by measles in children, and in China, Coxsackie

virus infection in children with selenium deficiency leads to severe

endemic juvenile cardiomyopathy (Keshan disease). Conversely,

acute infection can precipitate clinical deficiency in those with

borderline vitamin A status, resulting in visual loss.

Blood tests: measurement of blood nutrient levels is seldom a

good indicator of overall body status in patients with infection. The

main reason is the presence of the acute-phase response, which,

by sequestration of nutrients, may be an adaptive mechanism to

create an internal environment less conducive to the proliferation of invading organisms. For example, the increased levels of

iron-binding proteins and reduced availability of iron seen in the

acute-phase response may inhibit growth of some micro-organisms

with a high requirement for iron (e.g. malaria). In this situation,

improving iron status may exacerbate the pathology and increase

morbidity and mortality. Similarly, the up-regulation of circulating

lipid levels seen in infection may have a nonspecific binding effect

on both bacteria and viruses.

Albumin levels also contribute little to nutritional assessment.

Albumin is a negative acute-phase reactant, production of which

is specifically down-regulated as part of the acute-phase reaction.

Furthermore, albumin concentrations are profoundly affected

by changes in capillary permeability, which are common in

infection.

Effect of infection on nutrition

Chronic severe infection has been recognized for centuries as a

cause of wasting. Infection impinges on nutritional state in three

principal ways anorexia, increased metabolic rate and catabolism of protein.

Anorexia is a common feature of many infective processes and

is probably the most important contributor to the wasting that

accompanies chronic infections such as HIV and tuberculosis. Proinflammatory cytokines are thought to be the primary mediators

of such anorexia and probably act via neuropeptides such as NPY.

Resting (basal) energy expenditure is usually increased by acute

infection, partly as a consequence of fever. However, this increase

in energy expenditure is often more than offset by conservation of

energy as a consequence of reduced activity. Thus, total energy

expenditure may be reduced in sick, inactive patients, and energy

requirements are easily overestimated in such situations. Although

negative energy balance is common, the usual cause is reduced

intake, not increased expenditure.

Clinical assessment tools: several tools are available for clinical assessment of nutritional risk. The British Association for

Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition has recently produced a Malnutrition Screening Tool based largely on BMI.1

Relationship between nutritional state and infection

Protein metabolism: specific changes in protein metabolism occur

in infection. Net protein balance in muscle (the largest protein

reservoir in the body) is shifted towards protein breakdown, and

liberated amino acids are used partly to fuel the acute-phase

response. However, there is a net excess of breakdown over

utilization, resulting in increased nitrogen excretion, which may

exacerbate renal failure. The net effect on muscle is loss of functional tissue, resulting in weakness and fatiguability. This may

be sufficiently severe to compromise muscle groups essential for

respiration, coughing and posture, putting the patient at risk of

further infectious complications.

Malnutrition and susceptibility to infection

There are multiple mechanisms by which malnutrition increases

susceptibility to infection. The barrier functions of skin and mucosa

are the first line of defence against infection and are compromised

by malnutrition. Cellular and humoral immune function are markedly impaired in individuals with energy or protein deficiency.

These effects are more marked at the extremes of age. The perinatal

period is a crucial period when the developing immune system,

particularly the thymus, is susceptible to nutritional deprivation.

Elderly individuals may already have age-related immune dysfunction (immunosenescence) and are at greater risk of both infection

and malnutrition.

As a consequence, malnourished patients experience more

frequent and more severe infective episodes, as has been shown

for postoperative infective complications in malnourished patients

admitted for surgery.

Nutritional management

Macronutrients

The key approach to nutritional support in infection is provision

of adequate but not excessive nutrients. Processing of excess

Levels of malnutrition defined by body mass index

Normal

Marginal

Mild malnutrition

Moderate malnutrition

Severe malnutrition

BMI (kg/m2)

> 20

18.520

1718.5

1617

< 16

MEDICINE 33:3

15

2005 The Medicine Publishing Company Ltd

DEFENCE AGAINST INFECTION

nutrients may use essential substrates, and this may be the reason

why excessive nutritional support (hyperalimentation) can increase

morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients. Excess energy

tends to be accumulated as fat rather than useful lean tissue and

probably contributes little to the clinical outcome. Furthermore,

potent anabolic agents (e.g. growth hormone) increase mortality

in severely ill ICU patients, possibly by redirection of substrate

metabolism towards tissue anabolism and away from the acutephase response.

Inadequate nutrition leads to wasting, however, and such wasting increases morbidity, delays recovery, and predisposes patients

to further infective episodes. Dietary advice may be helpful and has

been the subject of a recent Cochrane review.2 When oral intake is

possible but inadequate, supplements may be helpful in achieving

weight gain or limiting weight loss. Enteral nutrition is the route

of choice whenever possible. In severely ill patients, energy is

usually provided at a rate of 2530 kcal/kg/day. Optimal protein

intakes are probably about 11.5 g/kg/day, though fixed-proportion

enteral feeds are often used, usually giving about 40 g protein per

1000 kcal energy. Protein losses associated with dialysis or drainage of ascites may demand greater protein intakes. Fluid volume,

electrolyte (particularly phosphate) and glycaemic control are also

of paramount importance in severely ill malnourished patients.

In famine situations, severely malnourished adults (BMI

< 13 kg/m2) have a very high mortality rate, primarily as a result

of infection. The presence of oedema, perhaps analogous to

kwashiorkor in children, is a poor prognostic sign, and mortality

in such patients is lower if the initial refeeding diet is relatively

low in protein.

Garrow J S, James W P T, Ralph A. Human nutrition and dietetics.

Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1999.

Macallan D C. Nutrition and immune function in human

immunodeficiency virus infection. Proc Nutr Socc 1999; 58: 7438.

(Review of interactions between HIV and nutrition, with particular

emphasis on mechanisms of wasting.)

McWhirter J P, Pennington C R. Incidence and recognition of malnutrition

in hospital. BMJJ 1994; 308: 9458.

Management of severe malnutrition: a manual for physicians and other

senior health workers. Geneva: WHO, 1999.

(Primarily focused on children and developing countries.)

Schwenk A, Macallan D C. Tuberculosis, malnutrition and wasting. Curr

Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2000; 3: 28591.

Villamor E, Fawzi W W. Vitamin A supplementation: implications for

morbidity and mortality in children. J Infect Dis 2000; 182: (Suppl. 1):

S12233.

Micronutrients

Micronutrients should be considered in all acutely unwell patients

who are unable to maintain adequate intake or are losing weight.

They may be given as part of complete nutritional formulas or

as separate supplements. Some nutrients (e.g. glutamine) may be

conditionally essential; that is, they become a requirement in

conditions of excessive demand. Use of specific nutrient formulations has been proposed for infective illnesses, but there is currently no evidence for this approach. However, future approaches

to nutritional management are likely to include disease-specific

supplementation or foodstuffs (so-called nutriceuticals).

Practice points

Measure weight regularly to predict malnutrition before it

becomes clinically apparent

Include a height measure or estimate to calculate BMI

Use a clinical malnutrition screening tool

Negative energy balance leads to wasting and must be

corrected whenever possible

Avoid excessive nutritional support it may harm rather than

benefit

Blood tests for nutrient status may be misleading in the

presence of infection

REFERENCES

1 British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Malnutrition

screening tool. www.bapen.org.uk/the-must.htm

2 Baldwin C, Parsons T, Logan S. Dietary advice for illness-related

malnutrition in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Revv 2001; 2:

CD002008. www.cochrane.org/cochrane/revsabstr/AB002008.htm

FURTHER READING

Calder P C, Field C J, Gill H S. Nutrition and immune function. Wallingford:

CABI, 2002.

(A comprehensive book on nutrient-immune interactions.)

MEDICINE 33:3

16

2005 The Medicine Publishing Company Ltd

También podría gustarte

- Palliative CareDocumento4 páginasPalliative CaresobanAún no hay calificaciones

- The Immunocompromised Patient Primary ImmunodeficienciesDocumento2 páginasThe Immunocompromised Patient Primary ImmunodeficienciessobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Rome III Diagnostic Criteria FGIDsDocumento14 páginasRome III Diagnostic Criteria FGIDsPutu Reza Sandhya PratamaAún no hay calificaciones

- Vulval PainDocumento3 páginasVulval PainsobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Medicolegal Issues and STIsDocumento3 páginasMedicolegal Issues and STIssobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Gastroenterology and AnaemiaDocumento5 páginasGastroenterology and Anaemiasoban100% (1)

- Urinary Tract ObstructionDocumento3 páginasUrinary Tract ObstructionsobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Acr Omega LyDocumento3 páginasAcr Omega LysobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Antineoplastic SDocumento20 páginasAntineoplastic SsobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Antiphospholipid SyndromeDocumento4 páginasAntiphospholipid SyndromesobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Autonomic & NeuromuscularDocumento20 páginasAutonomic & Neuromuscularzeina32Aún no hay calificaciones

- Adolescent NutritionDocumento1 páginaAdolescent NutritionsobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Disorders of PubertyDocumento2 páginasDisorders of PubertysobanAún no hay calificaciones

- The Wheezing InfantDocumento4 páginasThe Wheezing InfantsobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Cara Membaca Foto Thoraks Yang BaikDocumento2 páginasCara Membaca Foto Thoraks Yang BaikIdi Nagan RayaAún no hay calificaciones

- Neuro DegenerativeDocumento11 páginasNeuro DegenerativesobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Analgesic & AntimigraineDocumento12 páginasAnalgesic & AntimigraineChin ChanAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Scenarios Nutrition Growth and DevelopmentDocumento4 páginasCase Scenarios Nutrition Growth and DevelopmentsobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Neuro DegenerativeDocumento11 páginasNeuro DegenerativesobanAún no hay calificaciones

- What's New in Respiratory DisordersDocumento4 páginasWhat's New in Respiratory DisorderssobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Drugs That Damage The LiverDocumento5 páginasDrugs That Damage The LiversobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Non Epileptic Causes of Loss of ConsciousnessDocumento3 páginasNon Epileptic Causes of Loss of ConsciousnesssobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Haemo Chroma To SisDocumento4 páginasHaemo Chroma To SissobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Contraception: What's New in ..Documento4 páginasContraception: What's New in ..sobanAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is DiabetesDocumento2 páginasWhat Is DiabetessobanAún no hay calificaciones

- AppendixC NutrientChartDocumento5 páginasAppendixC NutrientChartArianne Nicole LabitoriaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Management of Acute Renal FailureDocumento4 páginasThe Management of Acute Renal Failuresoban100% (1)

- Whats New in Asthma and COPDDocumento3 páginasWhats New in Asthma and COPDsobanAún no hay calificaciones

- Renal Disease and PregnancyDocumento4 páginasRenal Disease and PregnancysobanAún no hay calificaciones

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (119)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2099)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- (15th June - 21st June) Weekly Webinars ScheduleDocumento1 página(15th June - 21st June) Weekly Webinars ScheduleSahil DhamijaAún no hay calificaciones

- Directed Writing and Essays On HealthDocumento8 páginasDirected Writing and Essays On HealthAtiqah AzmiAún no hay calificaciones

- Essential Oils Ancient Medicine-eBook PDFDocumento511 páginasEssential Oils Ancient Medicine-eBook PDFAlina Serban Leahu100% (20)

- Exam Patient Safety AwarenessDocumento5 páginasExam Patient Safety AwarenessidzniAún no hay calificaciones

- FNCPDocumento2 páginasFNCPJaylove CastilloAún no hay calificaciones

- Community & Public HealthDocumento3 páginasCommunity & Public HealthPark GwynethAún no hay calificaciones

- Critical Appraisal Untuk Artikel Terapi Scenario 1Documento7 páginasCritical Appraisal Untuk Artikel Terapi Scenario 1Sumendhe Hayuning SukmaraniAún no hay calificaciones

- Intrauterine Insemination (IUI)Documento21 páginasIntrauterine Insemination (IUI)Chanta MaharjanAún no hay calificaciones

- Gardasil Contract FDA Merck and Norwegian Government2Documento7 páginasGardasil Contract FDA Merck and Norwegian Government2Dustin EstesAún no hay calificaciones

- Covid-19 Crew Travel SafetyDocumento11 páginasCovid-19 Crew Travel SafetyВладимир Швец100% (1)

- Sample FNCP For InfectionDocumento3 páginasSample FNCP For InfectionAnonymous gHwJrRnmAún no hay calificaciones

- WebpdfDocumento461 páginasWebpdfTatiana RoaAún no hay calificaciones

- Pregnancy Nausea and Vomiting GuideDocumento16 páginasPregnancy Nausea and Vomiting Guidezakariah kamalAún no hay calificaciones

- Human Health & DiseaseDocumento58 páginasHuman Health & DiseaseSujay TewaryAún no hay calificaciones

- ICDSDocumento30 páginasICDSMadhu Ranjan100% (1)

- (EPI) 2.06 Community Diagnosis - DR - ZuluetaDocumento4 páginas(EPI) 2.06 Community Diagnosis - DR - ZuluetapasambalyrradjohndarAún no hay calificaciones

- Donning and Doffing Personal Protective Eqquipment (Ppe) : PreparationDocumento2 páginasDonning and Doffing Personal Protective Eqquipment (Ppe) : PreparationPam RuizAún no hay calificaciones

- Guide to Breech Presentation DeliveryDocumento13 páginasGuide to Breech Presentation DeliveryRahmawati Dianing PangestuAún no hay calificaciones

- Risk Assessment Template For Multi-Task Activities: Office Work ExampleDocumento4 páginasRisk Assessment Template For Multi-Task Activities: Office Work ExampleGorack ShirsathAún no hay calificaciones

- Scutchfield and Kecks Principles of Public Health Practice 4th Edition Erwin Solutions ManualDocumento3 páginasScutchfield and Kecks Principles of Public Health Practice 4th Edition Erwin Solutions Manuala710108653Aún no hay calificaciones

- The Relationship Between The Number of People With Immunity Against Covid-19 and Achieving Herd Immunity in Bangkok and The Vicinitiesareaof ThailandDocumento9 páginasThe Relationship Between The Number of People With Immunity Against Covid-19 and Achieving Herd Immunity in Bangkok and The Vicinitiesareaof ThailandIJAR JOURNALAún no hay calificaciones

- PreviewDocumento47 páginasPreviewRosario De La CruzAún no hay calificaciones

- COVID Business Liability BillDocumento42 páginasCOVID Business Liability BillMichelle Rindels100% (1)

- Microbiology of Water by Huzaifa FarooqDocumento16 páginasMicrobiology of Water by Huzaifa FarooqZaifi KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- NSO Level 1 Class 5 Question Paper 2019 Set B Part 11Documento4 páginasNSO Level 1 Class 5 Question Paper 2019 Set B Part 11Anubhuti GhaiAún no hay calificaciones

- Abnormal Labor - ClinicalKeyDocumento32 páginasAbnormal Labor - ClinicalKeyJunior KenAún no hay calificaciones

- VaccinationsDocumento31 páginasVaccinationsحامد يوسفAún no hay calificaciones

- Menstrual Hygiene Among Adolescent Girls Studying.34Documento6 páginasMenstrual Hygiene Among Adolescent Girls Studying.34riniandayaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Kevin Norbury in A Buggy Built For Him As A ChildDocumento6 páginasKevin Norbury in A Buggy Built For Him As A Childvaccine truthAún no hay calificaciones

- Urban HEP in Ethiopia XDocumento19 páginasUrban HEP in Ethiopia Xበተግባር ግዛቸውAún no hay calificaciones