Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Estimating The Costs of Medicalization 2010 Social Science Medicine

Cargado por

Renata VilelaTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Estimating The Costs of Medicalization 2010 Social Science Medicine

Cargado por

Renata VilelaCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Social Science & Medicine 70 (2010) 1943e1947

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Social Science & Medicine

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/socscimed

Short report

Estimating the costs of medicalization

Peter Conrad a, *, Thomas Mackie a, Ateev Mehrotra b

a

b

Department of Sociology, MS-71, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA 02454, United States

Rand Corporation, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

a r t i c l e i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Available online 10 March 2010

Medicalization is the process by which non-medical problems become dened and treated as medical

problems, usually as illnesses or disorders. There has been growing concern with the possibility that

medicalization is driving increased health care costs. In this paper we estimate the medical spending in

the U.S. of identied medicalized conditions at approximately $77 billion in 2005, 3.9% of total domestic

expenditures on health care. This estimate is based on the direct costs associated with twelve medicalized conditions. Although due to data limitations this estimate does not include all medicalized

conditions, it can inform future debates about health care spending and medicalization.

2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Medicalization

Cost of health care

Health spending

USA

Introduction

The percent of the U.S. gross domestic product spent on health

care has risen from 4.5% in 1950 to 16% in 2006 (Congressional

Budget Ofce, 2008). Numerous explanations have been offered

for this increase including the development and use of medical

technology (Rettig, 1994), the aging population (Reinhardt, 2003),

and particular reimbursement mechanisms (Bodenheimer, 2005).

Critics have suggested medicalization as another potential explanation for increasing health care costs (Budetti, 2008; Hadler, 2008;

Szasz, 2007), but to our knowledge no previous studies have

systematically tried to estimate the costs of medicalization. In this

paper we dene medicalization, present a strategy for estimating

the cost burden of medicalized conditions, and estimate 2005 US

spending on medicalized conditions.

For more than three decades numerous scholars have described

the process of medicalization and how an increasing number of

conditions has come under medical jurisdiction (Conrad &

Schneider, 1992; Zola, 1972). Medicalization is a process by which

non-medical problems become dened and treated as medical

problems, usually in terms of illnesses or disorders. Examples

include menopause, alcoholism, attention decit hyperactivity

disorder (ADHD), post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anorexia,

infertility, obesity, sleep disorders, erectile dysfunction (ED), among

others (14). The growing interest in medicalization is seen in the

number of symposiums about medicalization in places such as the

British Medical Journal (Special Issue on Medicalization, 2007), the

Presidents Council of Bioethics (Kass, 2003), PLoS (Moynihan &

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: conrad@brandeis.edu (P. Conrad).

0277-9536/$ e see front matter 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.019

Henry, 2006), and Lancet (Metzl & Herzig, 2007). In both the

social science and medical literature, the major focus has been on

documenting the rise in medicalization, debating conditions which

constitute medicalization, and identifying the implications for

patients, medicine and society.

An underlying theme in this literature is the concern about

overmedicalization. While medicalization describes a social

process, like globalization or secularization, it does not imply that

a change is good or bad. Some observers have raised the concerns

that medicalization is an over-expansion of medicines professional

jurisdiction and is a mechanism by which the pharmaceutical

industry can increase markets, thus contributing to rising health

care costs (Moynihan & Cassels, 2005). While these issues have

been raised repeatedly, to our knowledge, no analysis of medicalization has attempted to estimate the scal impact on health care

spending. Recognizing that there are many difculties in such

a task, not the least of which is dening what conditions are forms

of medicalization, we believe such an estimate would be an

important addition to the literature. While it is clear that in the last

three decades there has been a signicant growth in the number of

medicalized conditions as well as number of patients treated for

those conditions (Conrad, 2007), we seek to address what contribution this trend has had on the societal problem of spiraling health

care costs.

Methods

Identifying medicalized conditions

A key issue in this study was to identify medicalized conditions.

Selection of medicalized conditions was based on two criteria: 1)

1944

P. Conrad et al. / Social Science & Medicine 70 (2010) 1943e1947

a published study identied the condition as an example of medicalization since 1950 (Ballard & Elston, 2005; Barsky & Boros, 1995;

Conrad, 1992, 2007) and 2) the availability of reasonably valid and

current data on US national medical expenditures for that condition. In the end, we included 12 conditions (see Table 1). Schizophrenia and bipolar illness (manic depressive disorder) were

deemed a medical problem before 1950 (even as bipolar illness has

become a more common diagnosis in recent years). We were

unable to nd reliable national estimates for medicalized conditions such as eating disorders, idiopathic short stature, chronic

fatigue syndrome, and bromyalgia (Conrad, 2007). Due to the

limited availability of data, we only included costs of pharmaceutical drugs for erectile dysfunction and male pattern baldness, and

for obesity we only estimated the costs of bariatric surgery and

weight loss medication, excluding medical visits.

We recognize that medicalization is dimensional and on

a continuum; there are degrees of medicalization from conditions

that are thought to be minimally medicalized (e.g. sexual addiction

or multiple chemical sensitivity disorder) to almost completely

medicalized (e.g. childbirth or major depression). Once established,

medicalized categories can be exible, expanding or contracting.

For example, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) emerged in the

1970s as an ailment among Viet Nam veterans (Young, 1995) but

now PTSD includes survivors of all kinds of trauma (e.g., physical,

sexual, environmental, etc.) and even witnesses to traumatic

events. Medicalization has variable involvement from the medical

profession. For example, alcoholism treatment involves relatively

few physicians, while physicians play a central role in surgeries

such as gastric bypass for obesity. Finally, medicalization is bidirectional. While the trend has been overwhelmingly toward

increased medical categories and interventions in the past four

decades, there are a few examples of demedicalization, such as the

demedicalization of homosexuality since the 1973 APA decision

(Bayer, 1985). Thus the selected conditions were, at the time of data

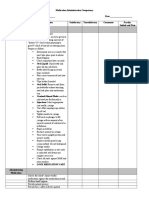

Table 1

Medicalized conditions.

Medical condition

Dened by diagnosis of the following condition or use

of the indicated health services or pharmaceutical

Anxiety disorders

Social phobia, anxiety states, dissociative, conversion

and factitious disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder,

neurasthenia, depersonalization disorder.

Behavioral disorders

Attention decit disorder without and with mention of

hyperactivity, conduct disorder, and oppositional

deant disorder.

Body image

Cosmetic procedures and surgeries (does not include

bariatric surgery.)

Erectile dysfunction

Pharmaceutical use of Viagra, Cialis, Levitra.

Infertility

Includes primary and secondary female infertility and

primary male infertility.

Male pattern baldness Pharmaceutical use of Propecia, Rogaine, and Minoxidil.

Menopause

Pharmaceutical use of Premarin family.

Normal pregnancy

In-patient deliveries, excludes all non in-patient

and/or delivery

deliveries and those with complications (e.g.,

hypertensions or diabetes complicating childbirth,

early labor or prolonged delivery, and malpositioned,

obstructed, or foreign deliveries). Caesarean sections

are included in this analysis unless they had been coded

as a complication of birth.

Normal sadness

Expansion of depression to include normal sadness

between 1990 and 2000.

Obesity

Bariatric surgery and weight loss medications.

Sleep disorders

Treatment for insomnia.

Substance related

Treatment for alcohol, amphetamine, cannabis, cocaine,

disorders

inhalant, nicotine, opioid, phencyclidine, and sedative

dependence.

Table 1 lists the 12 medicalized conditions included in this study. The table also

species the way in which each condition is dened for the purposes of this study.

collection, predominantly under medical jurisdiction being both

dened and treated medically.

Estimating the cost of the twelve conditions

Cost-of-illness studies use a systematic method to identify and

to calculate direct and indirect costs of treating and managing

a particular condition or illness (Rice, 1994). In this study, our focus

is specically on how medicalized diagnostic categories increase

national health care expenditures. Medical direct costs are dened

as payments to hospitals, pharmacies, physicians, and other health

care providers. These costs may be paid by the individual and their

family, private and public insurance, or other payment sources. We

therefore exclude non-medical direct and indirect costs such as

transportation costs and decreased productivity or missed work.

This study uses multiple data sources that were ranked

according to the empirical strength of each data source. Our use of

multiple data sources is similar to how the federal government

estimates national health expenditures yearly (Mehrotra, Dudley, &

Luft, 2003). Our primary source was 2005 data from the Medical

Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), released by the Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality AHRQ, 2008. MEPS is a nationally

representative dataset of the non-institutionalized population in

the United States (Cohen, 1997). The dataset has been widely used

to estimate the medical expenditure related to different types of

conditions or types of care (Chan, Zhan, & Homer, 2002; Sturm,

2002; Trogdon & Hylands, 2008). For each household in their

panel, MEPS regularly collects detailed information for each person

in the household on the following: demographic characteristics,

health conditions, health status, use of medical services, charges

and source of payments, access to care, satisfaction with care,

health insurance coverage, income, and employment. MEPS then

goes to each of the individuals identied providers and collects

data on dates of visits/services, use of medical care services, charges

and sources of payments and amounts, and diagnoses and procedure codes for medical visits/encounters (AHRQ, 2008).

Priority was given to these data for multiple reasons. First, the

database allows for primary analyses of national expenditures for

many of the identied medicalized conditions. The use of these data

as our primary data set aimed to strengthen this study by reducing

variation in the design and estimation techniques. Second, MEPS

uses person level weights to generate a nationally representative

sample and to correct for selection bias. Finally, numerous other

studies have used the MEPS data to document the cost of health

conditions ranging from pregnancy to pediatric behavioral health

care (Guevara, Mandell, Rostain, Zhao, & Hadley, 2003; Machlin &

Rohde, 2007). While data from MEPS were used when available,

estimates were next selected from peer-reviewed publications,

technical reports, annual sales reports from pharmaceutical companies, and lastly newspaper articles. The reliability of technical reports,

annual sales reports, and newspapers are limited as these data points

have not undergone scholarly review. We recognize that these data

have limitations, but felt they were necessary for an initial estimation

for the cost of medicalization that will require further renement.

Table 2 provides a list of the data sources used in this study, specifying

the type of data source, type of health service utilization, medical

conditions, and the payers of these services, when available.

This study implements three estimation techniques to ascertain

the impact of medicalization on national health care spending.

First, medicalized diagnostic conditions are used to identify relevant costs for medical care and treatment. This estimation technique is the strongest, by assuring that all medical expenditures are

linked to the medicalized condition. As described in Table 2, this

strategy is used for uncomplicated pregnancy, anxiety disorder,

substance related disorder, behavioral disorders, and infertility.

P. Conrad et al. / Social Science & Medicine 70 (2010) 1943e1947

1945

Table 2

Description of data sources and estimation techniques.

Data source (citation)

Type of data Type of health

source

service utilization

Medical

conditions

Medical expenditure panel survey

(AHRQ, 2008)

Primary data * In-patient visits

* Out-patient

analysis &

peerofce visits

* Emergency

reviewed

journal

department

visits

* Pharmaceutical

drugs

* Uncomplicated * Private and

public sector

pregnancy

* Out-of-pocket

* Anxiety

expenditures

disorder

* Substance

related

disorder

* Behavioral

disorders

* Female

infertility

* Male infertilitya

* Normal sadness * Private and

public sector

* Out-of-pocket

expenditures

* In-patient visits

* Out-patient

ofce visits

* Emergency

department

visits

* Pharmaceutical

drugs

* In-patient visits

National ambulatory and medical

Peer* Out-patient

care survey (Walsh & Engelhardt, 1999)

reviewed

journal

ofce visits

* Emergency

department

visits

* Long-term care

* Pharmaceutical

drugs

Pharmaceutical companies (Berenson, 2007; Annual sales * Pharmaceutical

Eli Lilly & Company, 2006; Glaxo Smith

report

use, including

Kline, 2005; Pzer, 2005; Wyeth, 2007, p. 2)

Viagrac, Levitra,

& Cialis

* Pharmaceutical

use, including

Premarin family

* Pharmaceutical

Medical bulletin (Anonymous, 1998)

Technical

report

use, including

Propecia,

Rogaine, &

Minoxidil

National comorbidity study

(Greenberg et al., 2003)

Healthcare Utilization and Cost Project and

Medstat 2002 market-scan commercial

claims and encounter database (Encinosa,

Bernard, Steiner, & Chen, 2005)

Peerreviewed

journal

Peerreviewed

journal

American society for aesthetic plastic surgery Technical

survey (ASAPS) (American Society for

report

Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 2008)

Payer

Estimation techniques

For primary analysis of MEPS data, conducted

a weighted analysis for each medicalized

condition to reect complex sampling design of

the survey. Used Statistical Analysis Software

(SAS), Version 9.1.3TM.

Acquired estimate for annual medical

expenditure on sadness at 1990 and 2000 from

Greenberg et al., 2003. Adjusted both the 1990

and 2000 to 2005 dollars, and then subtracted to

arrive at an estimate for normal sadnessb.

* Insomnia

* Private and

public sector

* Out-of-pocket

expenditures

Acquired estimates for direct medical costs for

insomnia from Walsh and Engelhardt study, and

then adjusted the 1994 to 2005 US dollars.

Estimate of male infertility, arrived from National

Ambulatory Care Society, adjusted estimation to

2005 dollars from 2000 dollars.

* Erectile

dysfunction

* Menopause

* Not available

(pharmaceutical sales)

Acquired annual sales reports for US sales of

Levitra, Cialis, and the Premarin Family. Viagra

estimate arrived from a 2007 New York Times

article, which reported annual sales in 2006 US

dollars. The estimate in 2006 US dollars was

adjusted to 2005 US dollars.

* Male pattern

baldness

* Not available

(pharmaceutical sales)

Acquired estimate from the Medical Bulletin,

which acquired estimates from the annual sales

reports of the respective distributors for US sales

of Propecia, Rogaine, and Minoxidil. All estimates

were adjusted from 1998 US dollars to 2005 US

dollars.

* Obesity,

* Obesity (Bari- * Private and

Acquired estimate for direct medical costs

including bariatric surgery

public sector associated with bariatric surgery and prescription

atric surgery and and weight loss * Out-of-pocket weight-loss medication from study by Encinosa

weight loss

medication)

expenditures et al. Estimates were adjusted from 2002 US

medication

dollars to 2005 US dollars.

* Body image,

* Body image

* Private and

Acquired 2005 estimate for invasive and nonincluding

(cosmetic

public sector invasive cosmetic surgeries and procedures.

cosmetic proceprocedures and * Out-of-pocket ASAPS provided survey to board-certied

dures and

surgeries)

expenditures physicians, across specialties with weighted

surgeries

analysis to derive national estimates.

Table 2 identies each data source, with specicity provided to the type of data source, the measures, the medicalized conditions, and the payer.

a

In addition to the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, the quotation for male infertility arrives from the National Ambulatory and Medical Care Survey, National Hospital

and Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, and the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (Meacham et al., 2007).

b

As stated in the text, we theorize this gure for normal sadness is likely as an overestimate, as not all increases between these two time periods can be attributable to the

rise in medicalizing normal sadness. Although hypothesized as an overestimate, our attribution of the difference in expenditure from 2000 to 1990 to normal sadness does

reect an empirical understanding articulated in the work of Horwitz and Wakeeld (2007).

c

The gure for U.S. sales of Viagra was found in a 2006 New York Times citation (Berenson, 2007).

Second, certain treatments were strongly enough associated with

a medicalized diagnostic condition that the treatments, themselves, are used to provide an estimate for the condition. This

estimation technique is used for menopause, male pattern baldness, erectile dysfunction, and obesity. Third, calculations of the

difference in expenditure over time are used to estimate the cost of

medicalized categories that have undergone expansion. This estimation technique is implemented for estimating the medicalization of normal sadness. Horwitz and Wakeeld identify the

expansion of clinical depression to include normal sadness

(Horwitz & Wakeeld, 2007). Sadness is used as a generic label for

normal mild to moderate depressive responses to various losses,

such as bereavement, severe physical illness, romantic betrayal or

rejection, economic misfortune, among others (Horwitz &

Wakeeld, 2007; Wakeeld, Schmitz, First, & Horwitz, 2007).

Therefore, we use the difference of ination-adjusted costs

between 2000 and 1990 to estimate the medical expenditure

associated with normal sadness. To adjust for ination in this paper,

this study uses the 2005 Consumer Price Index, issued by the

Bureau of Labor Statistics (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2008).

1946

P. Conrad et al. / Social Science & Medicine 70 (2010) 1943e1947

Results

Our estimate of the total direct health care costs in 2005

attributable to the twelve medicalized conditions was $77.1 billion.

This is 3.9% of the $1.97 trillion in total national health spending for

the United States in 2005 (Catlin, Cowan, Hefer, & Washington,

2007).

The two types of conditions that together make up almost half of

these expenditures are uncomplicated pregnancy and body image

services. Together the size of this bill is substantial, generating

a notable cost to the private and public sector, as well as consumers

themselves (Table 3).

Discussion and implications

There have been concerns that medicalization has been a major

driver of increased health care costs in the United States. We

estimate that the medicalized conditions we could identify make

up $77.1 billion in annual health care spending. This is a relatively

minor portion of national health care expenditures (<4%) and

therefore medicalization is unlikely to be a key driver of spiraling

health care costs. Yet, $77.1 billion represents a substantial dollar

sum. In comparison, $56.7 billion was spent on heart disease and

$39.9 billion was spent on cancer in the United States for 2000

(Thorpe, Florence, & Joski, 2004). The almost four percent of

health spending on medicalization is greater than the three

percent estimated to be spent on public health in 2005 (Budetti,

2008).

Our estimate could be, on aggregate, an underestimation of the

costs associated with medicalization. As discussed in the methodology, we have been conservative in our selection of medicalized

conditions and excluded conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar

disorder, or bromyalgia, and distinguished normal sadness from

Table 3

Estimated direct cost for select medicalized conditions in 2005.

Medical condition (citation)

Estimated direct

Year of original

medical cost 2005 data source

(in millions)

Anxiety Disorders (AHRQ, 2008)

Behavioral Disorders (AHRQ, 2008)

Body Image (Cosmetic procedures and

surgery) (American Society for

Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 2008)

Erectile Dysfunction (Berenson, 2007; Eli

Lilly and Company, 2006; Glaxo Smith

Kline, 2005; Pzer, 2005)

Infertility (AHRQ, 2008; Machlin & Rohde,

2007)

Male Pattern Baldness (Anonymous,

1998)

Menopause (Wyeth, 2007)

Normal Pregnancy and/or Delivery

(AHRQ, 2008)

Normal sadness (Greenberg et al., 2003)

Obesity (Bariatric surgery and weight loss

medication) (American Society for

Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 2008;

Encinosa et al., 2005)

Sleep Disorders (Walsh & Engelhardt,

1999)

Substance Related Disorders

(AHRQ, 2008)

Total

10,878.3

4657.5

12,376.0

2005

2005

2005

1112.1

2005; 2006

1104.2

2005; 2000

1055.1

1999

914.3

18,290.5

2006

2005

6204.0

1341.1

2000; 1990

2005; 2002

1,7684.5

1995

1468.7

2005

77,086.30

Table 3 provides the nal estimation cost for all medicalized conditions in 2005

dollars, disaggregated by condition. All data originally collected in a year other than

2005 have been adjusted for ination the 2005 Consumer Price Index, issued by the

Bureau of Labor Statistics (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2008).

clinical depression. On the other hand it is possible that our estimate could be also seen as an overestimate because in some cases

not all the costs related to a given condition are due to medicalization. For example, some might exclude the costs of treatment for

insomnia that is secondary to other medical therapy. Additionally,

the gure for normal sadness may be an overestimate, since not all

increases between these two time periods are likely attributable to

the rise in medicalizing normal sadness alone. Although other

factors may also contribute to the difference in medical expenditures on depression between 1990 and 2000, our attribution of the

difference in expenditure for increased medical treatment to

normal sadness aligns with the analysis of Horwitz and Wakeeld

(2007).

More important than whether our estimate is low or high is with

the policy implications of the cost estimate. As we noted above,

medicalization in itself does not connote whether this is good or

bad for health and society, only that problems have moved into

medical jurisdiction. But by estimating a dollar sum the obvious

question is raised as to whether this spending is inappropriate.

Taking this scal concern a step further, it raises the question of

whether policies should be in place to curb the growth or even

decrease the amount of spending on medicalized conditions. While

such policies could be introduced for particular conditions, we

believe such policies are generally not applicable to medicalization

overall. The individual and societal benets would need to be

carefully considered prior to any policy decision to curb or decrease

spending on these conditions.

These policy implications draw attention to the importance of

the economic, social, and political dimensions of health and health

care in the United States. First, there is a notable distinction

between spending by individuals and by employers, insurers, or

government. There is likely less societal concern when individuals

are paying out of pocket for cosmetic surgery or infertility treatment. Second, despite potential societal agreement that normal

childbirth has become too medicalized, we suspect there is unlikely

any societal desire for a wholescale move to the starkest alternative

of childbirth at home with no medical attention. Third, some

analysts have suggested that the pharmaceutical industry is the

major driver of medicalization in an effort to expand the potential

market for their drugs (Horwitz & Wakeeld, 2007; Moynihan &

Cassels, 2005). But individuals with these conditions may

perceive benet from and therefore desire medicalization because

external sources of payment become available when a problem is

dened as a medical ailment.

A next step would be to quantify further the economic and

societal consequences of medicalization. For example, one could try

and estimate the QALYs gained from treatment of erectile

dysfunction or insomnia. In such a cost-benet calculation, medicalized conditions might even be viewed as cost-effective. Future

research might elaborate on these important questions to shed

greater light on the intersections between the social, economic, and

political consequences of medicalization.

There are numerous limitations to our analyses. First and foremost, there is controversy about what is and what is not a medicalized condition. We have attempted to partly resolve this

controversy by using other published studies as a basis for choosing

conditions. Nonetheless, we suspect there will be debate among

readers on whether the twelve conditions were correctly chosen.

Another limitation is that potential off-sets may exist between the

use of health-related direct costs and other non-medical interventions. For example, the provision of medicalized services for

ADHD may deter costs for school-based interventions. These cost

savings to other stakeholders in child health are not accounted for

in this study and remains an area for additional study. Finally, the

quality of the data on direct costs was the best available but is not

P. Conrad et al. / Social Science & Medicine 70 (2010) 1943e1947

without biases due to varied data sources, estimation techniques,

and multiple years of data. Future research would benet from

constructing a stronger cost estimate, specically direct costs for

medicalized conditions from a single data source in the same scal

year.

While we recognize the limitations of this work and the need for

future work to rene our estimates, this initial analysis sheds new

light on the scal impact of medicalization on health care. Although

we nd that these medicalized conditions constitute a small fraction of total health care spending, the expenditures of just over 77

billion dollars provides considerable reason for further attention to

the medicalization process. We offer our cost estimate to advance

the continuing debate and scholarship on the societal and

economic impacts of medicalization.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to the reviewers and editor for comments on an

earlier draft of this paper.

Appendix. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in

the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.019.

References

American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. (2008). Cosmetic Surgery National

Data bank.

Anonymous. (1998). Advances in the battle against male pattern baldness. Medical

Sciences Bulletin.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2008). Medicalization: a multidimensional concept. Medical Expenditure Survey 2005 [Data le]. Retrieved from

http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data_les.jsp.

Ballard, K., & Elston, M. (2005). Medicalization: a multi-dimensional concept. Social

Theory and Health, 3, 228e241.

Barsky, A., & Boros, J. (1995). Somatization and medicalization in the era of managed

care. JAMA, 274, 131e134.

Bayer, R. (1985). Homosexuality and American psychiatry: The politics of diagnosis.

Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Berenson, A. (2007). Minky viagra? Pzer doesnt want you to understand it, just

buy it. New York Times (Business/Financial Desk) New York, Section C, 1.

Bodenheimer, T. (2005). High and rising health care costs. Part 3: the role of health

care providers. Annals of Internal Medicine, 142(12), 996e1002.

Budetti, P. (2008). Market justice and U.S. health care. JAMA, 299(1).

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2008). Consumer price index. United States Department

of Labor.

Catlin, A., Cowan, C., Hefer, S., & Washington, B. (2007). National health spending

in 2005: the slowdown continues. Health Affairs, 26(1), 142e153.

Chan, E., Zhan, C., & Homer, C. (2002). Health care use and costs for children with

attention-decit/hyperactivity disorder: national estimates from the medical

expenditure panel survey. Archives Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 156(5),

504e511.

Cohen, J. (1997). Methodology report #1: Design and methods of the medical expenditure panel survey household component. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care

Policy and Research.

Congressional Budget Ofce. (2008). Key issues in analyzing major health insurance

proposals. Congress of the United States.

1947

Conrad, P. (1992). Medicalization and social control. Annual Review of Sociology, 18,

209e232.

Conrad, P. (2007). The medicalization of society: On the transformation of human

conditions into treatable disorders. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

Conrad, P., & Schneider, J. (1992). Deviance and medicalization: From badness to

sickness (expanded ed.). Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Eli Lilly, & Company, I. (2006). 2005 annual report, notice of 2006 meeting. Indianapolis, IN: Proxy Statement.

Encinosa, W., Bernard, D., Steiner, C., & Chen, C. (2005). Use and costs of Bariatric surgery

and prescription weight-loss medications. Health Affairs, 24(4), 1039e1046.

Glaxo Smith Kline. (2005). Q4 results announcements 2005. Brentford: Glaxo Smith

Kline.

Greenberg, P., Kessler, R., Birnbaum, H., Leong, S., Lowe, S., Berglund, P., et al.

(2003). The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it

change between 1990 and 2000? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64(12),

1465e1475.

Guevara, J., Mandell, D., Rostain, A., Zhao, H., & Hadley, T. (2003). National estimates

of health services expenditure for children with behavioral disorders: an

analysis of the medical expenditure survey. Pediatrics, 112, e440ee446.

Hadler, N. (2008). Worried sick: A prescription for health in overtreated Amercia.

Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Horwitz, A., & Wakeeld, J. (2007). The loss of sadness: How psychiatry transformed

normal sorrow into depressive disorder. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kass, L. (2003). Medicalization: its nature, causes and consequences. June 12

session of the Presidents Council on Bioethics.

Machlin, S., & Rohde, F. (2007). Health care expenses for uncomplicated pregnancies.

Research Findings No. 27. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and

Quality.

Meacham, R., Joyce, G., Wise, M., Kparker, A., Niederberger, C., & Urologic Diseases in

America Project. (2007). Male infertility. The Journal of Urology, 177(6),

2058e2066.

Mehrotra, A., Dudley, R., & Luft, H. (2003). Whats behind the health expenditure

trends? Annual Review of Public Health, 24(1), 385e412.

Metzl, J., & Herzig, R. (2007). Medicalisation in the 21st century: introduction.

Lancet, 369(9562), 697e698.

Moynihan, R., & Cassels, A. (2005). Selling sickness: How the worlds biggest pharmaceutical companies are turning us all into patients. New York: Nation Books.

Moynihan, R., & Henry, D. (2006). The ght against disease mongering: Generating

knowledge for action. Public Library of Science Medicine, 3(4), e191.

Pzer, I. (2005). 2005 Financial report.

Reinhardt, U. (2003). Does the aging of the population really drive demand for

health care? Health Affairs, 22(6), 227e239.

Rettig, R. (1994). Medical innovation duels cost containment. Health Affairs, 13(3),

7e27.

Rice, D. (1994). Cost-of-illness studies: fact or ction? Lancet, 344(8936),

1519e1520.

Special Issue on Medicalization. (2007). British Medical Journal, 234(7342),

859e926.

Sturm, R. (2002). The effects of obesity, smoking, and drinking on medical problems

and costs. Health Affairs, 21(2), 245e253.

Szasz, T. (2007). The medicalization of everyday life. Syracuse: Syracuse University

Press.

Thorpe, K., Florence, C., & Joski, P. (2004). Which medical conditions account for the

rise in health care spending? Health Affairs, 23. w437ew445.

Trogdon, J., & Hylands, T. (2008). Nationally representative medical costs of diabetes

by time since diagnosis. Diabetes Care, 31(12), 2307e2311.

Wakeeld, J., Schmitz, M., First, M., & Horwitz, A. (2007). Extending the bereavement exclusion for major depression to other losses. Archive General Psychiatry,

64, 433e440.

Walsh, J., & Engelhardt, C. (1999). The direct economic costs of insomnia in the

United States for 1995. Sleep, 22(Suppl 2), S386eS393.

Wyeth. (2007). 4Q net revenue report. Madison, NJ: Wyeth Research.

Young, A. (1995). The harmony of illusions: Inventing post-traumatic stress disorder.

Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Zola, I. K. (1972). Medicine as an institution of social control. Sociological Review, 20

(4), 487e504.

También podría gustarte

- Fundações de Torres Eólicas - Estudo de Caso: January 2013Documento13 páginasFundações de Torres Eólicas - Estudo de Caso: January 2013Renata VilelaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Alienation of BodyDocumento30 páginasThe Alienation of BodyRenata VilelaAún no hay calificaciones

- TextsLaw Topology and ComplexityDocumento10 páginasTextsLaw Topology and ComplexityJorge Castillo-SepúlvedaAún no hay calificaciones

- Foucault As Theorist of TechnologyDocumento9 páginasFoucault As Theorist of TechnologyRenata VilelaAún no hay calificaciones

- Cord Blood in Vitro Growth of Granulocytic Colonies From Circulating Cells in HumanDocumento6 páginasCord Blood in Vitro Growth of Granulocytic Colonies From Circulating Cells in HumanRenata VilelaAún no hay calificaciones

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5795)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2104)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- Rules and Guidelines For Mortality and Morbidity CodingDocumento5 páginasRules and Guidelines For Mortality and Morbidity Codingzulfikar100% (2)

- Remifentanil Versus Propofol/Fentanyl Combination in Procedural Sedation For Dislocated Shoulder Reduction A Clinical TrialDocumento5 páginasRemifentanil Versus Propofol/Fentanyl Combination in Procedural Sedation For Dislocated Shoulder Reduction A Clinical TrialerinAún no hay calificaciones

- Nursing Care Plan For Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseDocumento17 páginasNursing Care Plan For Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseLyka Joy DavilaAún no hay calificaciones

- 12 Questions To Help You Make Sense of A Diagnostic Test StudyDocumento6 páginas12 Questions To Help You Make Sense of A Diagnostic Test StudymailcdgnAún no hay calificaciones

- Substance Abuse and Traumatic Brain Injury: John D. Corrigan, PHDDocumento50 páginasSubstance Abuse and Traumatic Brain Injury: John D. Corrigan, PHDSilvanaPutriAún no hay calificaciones

- Haemostatic Support in Postpartum Haemorrhage A.5Documento10 páginasHaemostatic Support in Postpartum Haemorrhage A.5Sonia Loza MendozaAún no hay calificaciones

- Epidemiology of Mental IllnessDocumento30 páginasEpidemiology of Mental IllnessAtoillah IsvandiaryAún no hay calificaciones

- Syphilis Is An STD That Can Cause LongDocumento3 páginasSyphilis Is An STD That Can Cause LongPaulyn BaisAún no hay calificaciones

- (Antonella Surbone MD, PHD, FACP (Auth.), Antonell (B-Ok - Org) 2Documento525 páginas(Antonella Surbone MD, PHD, FACP (Auth.), Antonell (B-Ok - Org) 2Anonymous YdFUaW6fBAún no hay calificaciones

- Methodology and Project Design 4Documento4 páginasMethodology and Project Design 4api-706947027Aún no hay calificaciones

- Breast AugmentationDocumento2 páginasBreast AugmentationAlexandre Campos Moraes AmatoAún no hay calificaciones

- 41ST Annual Intensive Review of Internal Medicine PDFDocumento3817 páginas41ST Annual Intensive Review of Internal Medicine PDFSundus S100% (2)

- PaediatricTuina Elisa RossiDocumento7 páginasPaediatricTuina Elisa Rossideemoney3100% (1)

- Invitation: Symposium On "Promoting Self-Care and Mental Health"Documento2 páginasInvitation: Symposium On "Promoting Self-Care and Mental Health"Alwin JosephAún no hay calificaciones

- 10th Monthly Compliance Report On Parkland Memorial HospitalDocumento92 páginas10th Monthly Compliance Report On Parkland Memorial HospitalmilesmoffeitAún no hay calificaciones

- Introduction To Chemicals in MedicinesDocumento5 páginasIntroduction To Chemicals in MedicinesP balamoorthyAún no hay calificaciones

- Internship Report Pharma CompanyDocumento19 páginasInternship Report Pharma CompanyMuhammad Haider Ali100% (1)

- Medication AdministrationDocumento3 páginasMedication AdministrationMonika SarmientoAún no hay calificaciones

- Great Critical Care ReliefDocumento9 páginasGreat Critical Care ReliefBenedict FongAún no hay calificaciones

- Ankyloglossia in The Infant and Young Child: Clinical Suggestions For Diagnosis and ManagementDocumento8 páginasAnkyloglossia in The Infant and Young Child: Clinical Suggestions For Diagnosis and ManagementZita AprilliaAún no hay calificaciones

- Meyer Et Al 2001Documento38 páginasMeyer Et Al 2001MIAAún no hay calificaciones

- Engel 1980 The Clinical Application of of The Biopsychosocial Model PDFDocumento10 páginasEngel 1980 The Clinical Application of of The Biopsychosocial Model PDFDiego Almanza HolguinAún no hay calificaciones

- Polymyalgia Rheumatic Symptoms Diagnosis and TreatmentDocumento2 páginasPolymyalgia Rheumatic Symptoms Diagnosis and TreatmentHas SimAún no hay calificaciones

- Triple Airway ManoeuvreDocumento3 páginasTriple Airway ManoeuvresahidaknAún no hay calificaciones

- Stress Hyperglycemia: Anand MosesDocumento4 páginasStress Hyperglycemia: Anand MosesDaeng Arya01Aún no hay calificaciones

- Congenital Adrenal HyperplasiaDocumento30 páginasCongenital Adrenal HyperplasiaIrene Jordan100% (1)

- Kansas College Immunization WaiverDocumento1 páginaKansas College Immunization WaiverDonnaAún no hay calificaciones

- Esophageal Perforation: Diagnostic Work-Up and Clinical Decision-Making in The First 24 HoursDocumento7 páginasEsophageal Perforation: Diagnostic Work-Up and Clinical Decision-Making in The First 24 HourssyaifularisAún no hay calificaciones

- Eshre Guideline Endometriosis 2022Documento192 páginasEshre Guideline Endometriosis 2022Patricia100% (1)

- Epilepsy MCQDocumento7 páginasEpilepsy MCQko naythweAún no hay calificaciones