Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

First Amendment 2011

Cargado por

DavidFriedmanDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

First Amendment 2011

Cargado por

DavidFriedmanCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

1

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

I.

GENERAL..............................................................................................................................2

A.

B.

C.

TEXT OF THE FIRST AMENDMENT........................................................................................2

THEORIES UNDERLYING FREEDOM OF SPEECH.....................................................................2

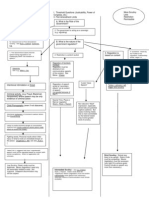

FLOWCHART OF FREE SPEECH INQUIRY...............................................................................3

II. RESTRICTIONS BASED ON COMMUNICATIVE IMPACT........................................4

A.

B.

C.

D.

E.

F.

G.

H.

I.

J.

K.

INCITEMENT..........................................................................................................................4

FALSE STATEMENTS.............................................................................................................6

OBSCENITY...........................................................................................................................9

VAGUENESS........................................................................................................................10

PRIOR RESTRAINTS.............................................................................................................11

SPEECH AS INTEGRAL PART OF CRIMINAL CONDUCT........................................................12

1. Child Pornography........................................................................................................12

2. Integral Part of [another] Crime..................................................................................13

OFFENSIVE SPEECH............................................................................................................14

SYMBOLIC EXPRESSION.....................................................................................................16

COMMERCIAL SPEECH/ADVERTISING.................................................................................17

STRICT SCRUTINY..............................................................................................................19

CONTENT DISCRIMINATION WITHIN UNPROTECTED SPEECH.............................................22

III. CONTENT-NEUTRAL RESTRICTIONS........................................................................24

A.

RESTRICTIONS ON SPEECH & EXPRESSIVE CONDUCT........................................................24

IV. SPECIAL BURDENS ON FREE SPEECH......................................................................27

A.

B.

C.

D.

V.

FORCED ASSOCIATION........................................................................................................27

SPEECH-RELATED SPENDING & CONTRIBUTIONS...............................................................29

SPEECH COMPULSIONS: DIRECT INTERFERENCE W/SPEAKERS OTHER SPEECH................31

SPEECH COMPULSIONS: INDIRECT INTERFERENCE W/SPEAKERS OTHER SPEECH.............34

GOVERNMENT ACTING IN SPECIAL CAPACITIES................................................36

A.

B.

C.

D.

GOVERNMENT AS EMPLOYER.............................................................................................36

GOVERNMENT AS POSTMASTER.........................................................................................38

GOVERNMENT AS LANDLORD: FORUM ANALYSIS.............................................................38

GOVERNMENT AS SUBSIDIZER/SPEAKER............................................................................40

VI. RELIGION CLAUSES.......................................................................................................44

A.

FREE EXERCISE..................................................................................................................46

1. Non-Discrimination Principle (Free Exercise).............................................................46

2. Compelled Exemptions & RFRA...................................................................................48

B.

ESTABLISHMENT CLAUSE...................................................................................................52

1. Non-Discrimination Principle (Establishment).............................................................53

2. Non-Discrimination Extended (No Endorsement Principle).........................................54

3. No Primary Religious Purpose Principle......................................................................56

4. No Coercion Principle...................................................................................................58

1

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

5.

Compelled Exclusions: Facially Even-Handed Funding Programs.............................59

I.

GENERAL

A.

TEXT OF THE FIRST AMENDMENT

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free

exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people

peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

B.

THEORIES UNDERLYING FREEDOM OF SPEECH

Why we value freedom of speech

Search for truth through the marketplace of ideas

Self-government and democracy

Autonomy, Self-Actualization, Self-Expression

Benefits of tolerance

Why we dont restrict speech

No Law means no law. Justice Black.

So many alternatives to suppressing speech that restrictions are unnecessary

If speech is harmless or restrictions dont work, theres no need to restrict

Best remedy for bad speech is good counter-speech

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

C.

FLOWCHART OF FREE SPEECH INQUIRY

1. State Action?

a. If not, First Amendment does not apply.

b. Is the state acting in a special capacity?

i. If acting toward the public as a sovereign, continue to #2

ii. If acting in a special capacity (employer, landlord, speaker,

subsidizer), go to #6

2. Does it restrict Speech or Expressive Conduct?

a. If not, First Amendment does it interfere with speech in some other

way? See #5.

b. Vagueness & Overbreadth: Is it unclear whether speech or expression

would be restricted? Or would some protected speech be impacted?

i. chilling effect

ii. Look to previous constructions of the statute

iii. Ask Court to create a limiting instruction

c. Expressive Conduct: Would someone know what the conduct means

without a sign or explanation? Rumsfeld v. FAIR; Texas v. Johnson.

3. Speech restricted for its Content or Communicative Impact?

a. If yes, is the speech unprotected? Less protected Commercial Speech?

i. If unprotected, is this restriction content-based discrimination

within an exception, banned under R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul?

ii. If protected, does the restriction pass strict scrutiny?

b. If not, continue

4. Speech restricted for reasons unrelated to the content or communicative

impact?

a. Apply forum analysis (Part III of textbook)

5. Interference with Speech other than through Direct Suppression?

a. Expressive Association

b. Spending Money on Speech

c. Compelled Speech

6. Government in special capacity? Possible lower level of scrutiny

a. Employer

b. Landlord/Postmaster

c. Subsidizer/Speaker (consider forum analysis)

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

II.

RESTRICTIONS BASED ON COMMUNICATIVE IMPACT

A

INCITEMENT

Blackletter: p.3

Incitement (Brandenburg v. Ohio p5): Advocacy of the use of force or violation of a law is

unprotected incitement when it is

1. Directed at inciting or producing

a. Subjective intent

2. Imminent lawless action

a. Within hours, or at most days

b. NOT some indefinite time in the future (Hess v. Indiana)

3. And is likely to incite such action

a. Objective likelihood

Solicitation (US v. Williams p7): A proposal to engage in illegal activity (not just abstract

advocacy of illegality) is unprotected, even if it is not imminent. Speech that is a crime unto

itself.

Cases:

Brandenburg (1969) p5

Rule: Advocacy of the use of force or of law violation is incitement when it is (a) directed to

inciting or producing (b) imminent lawless action (c) and is likely to produce such action.

Facts: KKK leader convicted under Ohio Criminal Syndicalism statute for advocating the

duty, necessity, or propriety of crime . . . as a means of accomplishing industrial or political

reform and voluntarily assembling with any society . . . formed to teach or advocate the

doctrines of criminal syndicalism. Speaker suggested that revengeance might be necessary if

the U.S. continues to suppress the white, Caucasian race.

Holding: This statute is unconstitutional because it fails to draw the distinction between abstract

advocacy of violence and preparing a group for violent action and steeling it to such action.

But see Yates, Dennis (1950s), Communist cases, which allowed restrictions on concrete action

even when it wasnt imminent. Technically not overruled.

US v. Williams (2008) p7

Facts: In an internet chat room, Williams offered pictures of his daughter engaging in sexually

explicit conduct for trade. Agent got a search warrant and found pictures of real minors engaging

in sexually explicit conduct or displaying their genitals. Williams pled guilty to pandering and

possession of child pornography, but challenged constitutionality of the pandering charge.

Holding: Offers to engage in illegal transactions are categorically excluded from First

Amendment protection. Draws a distinction between promotion or advocacy of child porn

and recommendation of a particular piece of purported child pornography with the intent of

initiating a transaction.

Older Tests, limited by Brandenburg to imminent lawless action:

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

Wartime Espionage Act Cases: Limited by Brandenburg to imminent lawless action test

Schenck (1919) convicted under the Espionage Act for conspiracy to obstruct military

recruiting in war time, for sending out pamphlets encouraging young men to oppose the

war and recruitment. The test is whether the words used are used in such circumstances

and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about

the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. Basically knowledge +

likelihood of illegal action (no imminence requirement).

Debs (1919, later) convicted under the Espionage Act for giving a speech praising people

who were convicted of obstructing the recruiting effort. Jury told that they cannot convict

unless the words used has as their natural tendency and reasonably probable effect to

obstruct the recruiting service, and unless the defendant has the specific intent to do so in

his mind.

Abrams (1919, later) convicted under the Espionage Act, for conspiring to print language

intended to incite, provoke and encourage resistance to the United States in said war.

They created 2 pamphlets encouraging workers to strike (up to fight!, stop creating

bullets, etc.), because they would be used against socialist revolutionaries in Russia.

Court holds that this intent isnt enough to save them, because they were aware that their

pamphlets would be likely to hinder the war effort in Germany. Strongly worded dissent,

saying this mens rea isnt enough for an attempt to hinder the war effort, so conviction is

unconstitutional.

Gilbert (1920), convicted under a Minnesota statute making unlawful oral or written

speech advocating that men should not enlist or assist the US in war. Conviction upheld.

Advocating Crime:

Gitlow (1925) was convicted of speech advocating the overthrow of organized

government by unlawful means. He wrote a Manifesto for the Left Wing of the Socialist

Party, advocating struggle and revolutionary mass action. Conviction upheld for

abuse of the freedom of speech. Basically, held that this is incitement (but the

likelihood of lawless action was small and there was little or no imminence/present

danger). Incorporates First Amendment against the States under the 14th Amendment.

Whitney (1927) conviction upheld under CA Criminal Syndicalism Act for organizing a

group assembled to advocate crime or violence to accomplish political change.

Communist, advocating strikes and the overthrow and conquest of capitalist rule.

Concurrence lays out something similar to Brandenburg (clear and present danger), but

determines that the acts here met that test.

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

D.

FALSE STATEMENTS

Theory: no constitutional value in false statements of fact; however, error is inevitable. First

Amendment require4s that we protect some falsehood in order to protect speech that matters.

Gertz, p 76

Blackletter: p 57

Must be a false statement of FACT (provably false factual connotation).

Not opinion, or parody

Can be an implicit statement of fact

Mens Rea requirement: False Statements of fact can be punished if they have a sufficiently

culpable mental state.

Deliberate lies

o okay if theyre about the government (seditious libel), as long as no particular

person is defamed. NY Times v. Sullivan.

o False statements about History, Science, or Current Events may be protected.

Knowingly (or recklessly) false statements of fact are usually punishable

o Malice standard, NY Times v. Sullivan

Negligence (Gertz)

o Private individuals, public concern

Strict Liability for matters of private concern? (Dun & Bradstreet)

Types of punishment that are constitutional (with the right mens rea)

Libel & Slander

Fraud

Perjury

False inducement of fear (Fire! or calling 911 and lying)

Flowchart for determining mens rea requirement for the speech to be unprotected: Chart p 62

(1) Public Figure, Public Concern

a. Actual Malice (knowledge of falsity or recklessness). NY Times v. Sullivan.

b. What is reckless disregard?

i. Publishing while actually entertaining doubts as to the truth

ii. Purposeful avoidance of the truth

(2) Private Figure, Public Concern

a. Negligence. Gertz.

(3) Anyone, Private Concern

a. Unclear. Maybe strict liability

b. See Dun & Bradstreet.

Who is a public figure? Pretty much anyone worth making statements about.

Government officials, unless WAY down on the totem pole

6

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

People who have assumed an influential role in society (beyond involvement in

community and professional affairs). Gertz.

People who have achieved pervasive fame or notoriety

Those who have voluntarily injected themselves (or been drawn into) a particular public

controversy

o Limited Purpose public figures, only as to that controversy

o Must be of public importance

o Low-profile criminal prosecution & high profile divorce case are not enough to

become a public figure.

What is of Public Concern? Anything worth printing.

Anything about an officials fitness for office

Anything article with a broad public purpose, even if the individual named in it is not a

matter of public concern. Florida Star v. BJF.

Speech in the interest of the speaker and a small audience is probably not a matter of

public concern. Esp. if it isnt likely to be deterred. Dun & Bradstreet.

Remedies: Punitive & Presumed damages available

Public Concern? only if actual malice is proved (knowledge or reckless)

Private Concern? Yes, even without actual malice (negligence)

Criminal Liability for Libel: Okay, within confines of rules applicable to civil suits

Burden of Proof: Public Concern? Burden is on the plaintiff (the one who got defamed)

Quantum of Proof: Proof of Knowledge or Recklessness must be Clear & Convincing

Cases:

New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) p 63

Facts: Police commissioner sues for libel based on a full-page ad accusing the police of abuse in

a Montgomery, AL, school in response to a protest against segregation. Plaintiff claims that the

word police and they refers to him.

Analysis: Puts burden on the government official to show that the false statement (against him

specifically) was made with actual malice (knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard of the truth

or falsity of the statement).

Holding: The Times was at most negligent, and the false statements were not of and

concerning the police commissioner personally. Goes on to say that For good reason, no court

has ever held, or even suggested, that prosecutions for libel on government have any place in

the American system of jurisprudence. Preserves liability for knowing/reckless falsehoods, and

seems to protect all falsehoods that address matters of public concern.

Dissent: Misinformation frustrates the values of the first amendment in criticism and assessment

of public officials. Information is polluted, and the public official remains defamed unless he can

prove knowledge or recklessness. (Mad about burden shifting)

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

[More cases over]

Gertz (1974) p 76 (damages, p 83)

Private Individual, Public Concern.

Facts: Gertz represented a youths estate in civil litigation against a police officer who shot and

killed the youth. A crazy newspaper published a false story about Gertz, claiming she is part of a

conspiracy to discredit police and replace them with a Communist dictatorship.

Analysis: False statements of fact are inevitable in free debate. Creating strict liability would

chill the press. Private citizens have little or no access to self-help through the media, so they

cant fight speech with speech, and the state has a greater interest in protecting them.

Held: So long as it is not strict liability, the states can create libel laws that allow for recovery for

false statements made against a private individual, even on a matter of public concern. But there

can only be recovery for actual injury; no presumed or punitive damages without knowledge or

recklessness.

Dun & Bradstreet (1985) Majority, p 87. Concurrence, White, p 72

Public Individual, Private Concern

Facts: Recklessly sent out reports to 5 individuals stating that a company filed for bankruptcy

(mistake imputed bankruptcy of a former employee to the company).

Analysis: This case is different from New York Times and Gertz because this is purely private

speech: No potential interference with open debate, no problems with criticizing the government,

no risk of self-censorship by the press. Therefore, there can be punitive and presumed damages

even without actual malice. A credit report is not a public concern: Those who read were

contractually obligated to not disseminate it, there is no public interest in a credit report (but

what about in the health of the company?), and this commercial speech, so it is naturally hardy.

Holding: This is a matter of private concern, and is unprotected.

Concurrence by White, p72: Critical of New York Times. Erroneous information does not further

First Amendment values because they detract from debate and confidence in government. The

actual malice test is too strong, and the burden is in the wrong place.

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

E.

OBSCENITY

Blackletter: p 114

Miller test: Speech is obscene (and unprotected) if:

1. The average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find that the

work, taken as a whole [and with respect to minors], appeals to the prurient interest, and

a. Prurient means lustful excitement, deviant, shameful or morbid interest in sex, or

too great of an interest in sex

2. The work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way [with respect to minors] under

contemporary community standards, sexual conduct specifically defined by the

applicable state law, and

3. The work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value

[for minors].

a. Based on a reasonable person, not an ordinary person in the community

Cases:

Miller v. California (1973): p116, p126, p128.

Facts: Unsolicited brochure with explicit images and a movie.

Held: Rejects the utterly without redeeming social value test (Roth, Memoirs). Remanded.

Paris Adult Theatre (1973): p124

Companion case to Miller. Upholds Georgia law prohibiting adult movie theatres.

Analysis: Legislature reached a conclusion that there is a correlation between obscene materials

and crime; court defers.

Dissent p 126: Consent (and age of majority) is what matters; these theatres are limited to willing

adults.

Roth (1957): p120

Presumed that obscene material was utterly without redeeming social importance.

Nine years later, Memiors v. MA held that to prohibit allegedly obscene material, it had to be

affirmatively proven to be utterly without redeeming social value.

10

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

F.

VAGUENESS

Blackletter: p. 133 & p. 168

Policy: Chilling effect on protected speech if a law restricting speech is vague or overbroad; must

give notice to citizens (due process) and guidance to police (preventing arbitrary enforcement)

Vagueness: p133; in Obscenity cases, p 128

A speech restriction can be unconstitutionally vague if it fails to provide an ascertainable

standard of conduct.

o If courts have interpreted the law in way that makes it less vague, then the court

considering the vagueness argument will look at the law as construed.

o Goguen: Notice plus Guidance (bottom p 137)

Overbreadth: p 133, 168-69

Can challenge a law for overbreadth under the First Amendment (restricts protected

speech), even if the law is constitutional as applied to that person. (unlike all other law)

o The overbreadth must be substantial

o Looks to the law as construed by the courts

Can also ask for a limiting instruction in the case at hand to preserve the

statute

o The overbreadth must relate to noncommercial speech

Policy: Three evils of overbreadth:

Need to know what is illegal to avoid the activity

Arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement

Chilling effect

Notes: Overbreadth can lead to vagueness. Jews for Jesus (p 503).

Cases:

Miller & Paris Adult Theatre (1973): p 128-29 Notice & Vagueness problems in obscenity laws

Grayned v. City of Rockford (1972) p 134

Facts: An Illinois law prohibits noise and disturbance near schools. The Illinois Supreme Court

interpreted tends to disturb as imminent interference with the peace and order of the school.

Analysis: The law, as interpreted by the state court, is not overly broad.

Smith v. Goguen (1974) p 137

Facts: Conviction under Flag Misuse statute for treat[ing] contemptuously the US flag, for

wearing it on the seat of pants.

Analysis: No definition of contempt. Need NOTICE and GUIDANCE to law enforcement.

Selective law enforcement is a due process denial.

[more cases over]

10

11

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

Board of Airport Commrs v. Jews for Jesus (1987) p 139

Facts: LAX purports to ban all First Amendment activities and suggests a limiting instruction

to only cover non-airport-related speech.

Analysis: Even if LAX were a nonpublic forum, this seems an absolute prohibition on speech.

Gives too much leeway to airport officials to decide what is airport-related. Gives police

unrestrained power.

Reno v. ACLU (1997) p 140

Facts: The Communications Decency Act (CDA) prohibits transmitting obscene material to

minors over the internet.

Analysis: Vagueness uses inconsistent terms (indecent v. offensive); leaves out safeguards from

Miller test (limiting obscenity to sexual conduct, required definitions of proscribed speech,

appeal to prurient interest, lack of value). [Ultimately ruled on overbreadth grounds]

Held: Overly broad.

Child Pornography (see below, under Speech as Integral Part of Criminal Conduct)

G.

PRIOR RESTRAINTS

Blackstone: believed that Prior Restraints were the only thing protected by Freedom of Speech.

You can print whatever you want, as long as youre prepared to take the consequences.

11

12

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

H.

SPEECH AS INTEGRAL PART OF CRIMINAL CONDUCT

1.

Child Pornography

Blackletter: p 142

Unprotected if (NY v. Ferber)

visually protects children below the age of majority

performing sexual acts or lewdly exhibiting their genitals

Supplants Miller when children are involved.

Concern is for children involved in production, not impact on society: the conduct is a violation

of the law, and the distribution is ongoing abuse of the child. (But, consider though that taping

other illegal acts is protected.)

Note: A person is only liable for distribution or possession if he knows or has reason to know that

the porn features an underage minor. Reasonable mistake of fact is a defense.

Only material using actual children is unprotected (Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition)

Cases:

NY v. Ferber (1982) p 144

Creates an exception to First Amendment protection for child porn. In that case, the speech is the

record of the crime of sexual abuse. Does NOT apply Mitchell (e.g. social value), because the

problem isnt the viewers reaction; its the abuse of children.

Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition (2002) p149

Court strikes down the CPPA because it is overbroad: prohibits any visual depiction of a minor

(or what appears to be a minor) engaging in sexually explicit activity, without regard to whether

any minors were involved OR whether it is obscene under Miller.

12

13

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

2.

Integral Part of [another] Crime

Blackletter: p156

The mere tendency of speech to encourage unlawful acts is not a sufficient reason for banning

it (Ferber)

Burden of proof remains on the government to show that the speech will lead to harm

States can prohibit unlawful action or conspiracy, even when it is carried out using speech, as

long as the speech is intrinsically related to the criminal conduct.

E.g. Here are the blueprints and secret combination to the bank. Now, go! or Your

money or your life!

Threats p 208: There is a threat exception to the First Amendment

o But, if it is obviously hyperbole, then it is not a threat

o On the other hand, some types of ambiguous activities will be held to be threats

depending on the history between the parties

E.g., in Virginia v. Black, the Court upheld a Virginia statute that outlawed

burning a cross with intent to intimidate, but struck down a provision that

treated burning a cross as prima facie evidence of intent to intimidate; a

threat has to be aimed at someone

o some types of threats are protected

E.g., threats of social ostracism, or of politically-motivated boycotts

Verbal acts: perjury, conspiracy, assault

Intellectual Property (Speech owned by Others): p221 copyright violations

Cases:

US v. Stevens (2010): p 156.

Facts: Man who ran a dogfighting website convicted under a law that prohibits possession,

distribution, and production of visual depictions of illegal animal cruelty. The law was adopted in

response to crush videos, where state cant prosecute the actor because the video hides her

identity.

Holding: The law is unconstitutionally broad because it proscribes videos describing even legal

activities, such as hunting. (Unlike in other areas of the law, the overbreadth of the law can be

challenged even by someone whose actions are actually proscribable).

Note: Court rejects any idea of a balancing test for First Amendment restrictions. Recharacterized the exception for child porn as one for speech that is intrinsically related to the

criminal conduct of child abuse.

Giboney v. Empire Ice (1949): p 165

Relied upon in Rumsfeld v. FAIR, US v. Williams, US v. Stevens.

Facts: Union pickets Empire to try to force it to abide by union rules (dont sell to non-union)

Held: State may prohibit picketing that interferes with trade.

Chaplinsky: See below, Offensive Speech.

13

14

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

I.

OFFENSIVE SPEECH

Blackletter: p 169

Fighting Words

Abusive Words

IIED on matters of private concern

Speech is unprotected fighting words if:

(1) It tends to incite an immediate breach of the peace by provoking a fight, so long as

(Chaplinsky)

(2) It is a personally abusive epithet which, when addressed to the ordinary citizen, is, as

a matter of common knowledge, likely to provoke a violent reaction (Cohen), and

(3) Is directed at the hearer and thus likely to be seen as a direct personal insult (Cohen).

Offensive Speech Exception:

May only apply to Low-Value speech epithets and vulgarities (Chaplinsky)

o but could also implicate political speech if it fits the other requirements of

fighting words (TX v. Johnson)

Never upheld a fighting words law since Chaplinsky. (Its reasoning, involving the

balancing of the social value of the speech and the countervailing social interests, might

have won the day in 1900; today, it wouldnt get a single vote)

What about Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress?

Not enforceable if the words are on a matter of public concern, Snyder v. Phelps.

Notes: Pages 170-73 list other possible rules based on dicta in cases. Offensive speech seems to

be based in part on the personal targeting of someone, and in part on whether the audience is

captive.

Cases:

Chaplinsky (1942) p 174

Facts: D, taken away from site of demonstration by police to prevent violence against him, calls

the marshal a racketeer and fascist and is prosecuted.

Holding: Fighting words, those which by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an

immediate breach of the peace, are not protected under the First Am. Resort to epithets or

personal abuse is not communication of information or opinion; it is no essential part of any

exposition of ideas. The statute in question was limited to statements with a direct tendency to

causing acts of violence and that were offensive to a common sensibility.

Note: This is the only case upholding a fighting words conviction.

Rowan v. US Post Office Dept (1970) p 178, Summary p 171

Captive Audience Rationale.

Facts: A federal law allows residents to block the sending of erotic materials to their homes.

Analysis: Residents are captive audiences. Residences must take affirmative steps to block the

information.

14

15

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

Held: Constitutional.

Cohen v. California (1971) p 175, 179

Limits Captive Audience rationale in Rowan (Avert your eyes); limits Chaplinsky (must be

directed at the person suffering the harm)

Facts: D is convicted of maliciously disturbing the peace by wearing a jacket stenciled with

Fuck the Draft at the county courthouse.

Holding: Even if the fighting words exception still exists, Ds jacket was not employed in a

personally provocative fashion. The mere presumed presence of unwitting viewers does not

automatically justify curtailment of all speech capable of giving offense. Those present could

have avoided further offense simply by averting their eyes. So long as Ds speech was

otherwise protected, its offensive nature alone is insufficient to justify criminalizing it. So long

as the means are peaceful, the communication need not meet standards of acceptability.

FCC v. Pacifica (1978) p 181, Summary p 171

Captive Audience Problem with broadcast makes banning certain epithets constitutional.

Distinguishes Cohen (written v. spoken cant avert your eyes to the radio).

Texas v. Johnson (1989) p 188

Flag burning

Facts: D is convicted of desecration of a venerated object for burning a flag at a political

demonstration.

Holding: Speech may not be banned because an audience that takes serious offense at particular

expression is likely to disturb the peace. Allowing such restriction would eviscerate both

Brandenburg and Cohen; thus, the states interest in maintaining order is not implicated by this

statute. The state may not foster its own view of the flag by prohibiting expressive conduct

relating to it or otherwise prescribe what ideas shall be orthodox. The First Am does not

guarantee that other concepts sacred to the nation shall go unchallenged in the marketplace of

ideas; the flag is no exception to this rule. We do not consecrate the flag by punishing its

desecration, for in doing so we dilute the freedom that this cherished emblem represents.

Dissent: argues the flag is truly unique and not simply a point of view competing for recognition

in the marketplace of ideas and that flag burning is merely the equivalent of an inarticulate grunt

or roar, not an expression of an idea.

Snyder v. Phelps (2011) p 191

Facts: Westboro Baptist Church protests at a military funeral, combining attack on the deceased

(Thank God for your dead son) with more general attacks on US tolerance for LGBT people.

Held: IIED verdict overturned because speech was on a matter of public concern. Doesnt matter

if it was in a private location or directed at a private party public concern is protected.

Dissent/Counterarguments: Some of the speech was not of public concern; how much is too

much? Captive audience at a funeral (except they couldnt see or hear the protesters). Special

sphere for grieving where speech can be restricted?

15

16

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

J.

SYMBOLIC EXPRESSION

Blackletter: p 205

Rule: 1A protects symbols, defined as conduct that:

Test 1

Intends to convey a particularized

message

Likelihood is great that the message

would be understood by viewers

Message is created by conduct itself.

Test 2

OR

Traditionally a protected genre

(e.g., painting, music, etc.)

Various roads are not taken by SCOTUS:

First Amendment does not apply to anything that is not words. (Hugo Black's position)

o Yet, flag burning was meant to communicate something (in context). After all,

flags are destroyed humanely by the military without anyone thinking that the

military is protesting.

First Amendment applies to all conduct that has a symbolic element.

o Trouble is, even horrific crimes can have a symbolic element.

Rumsfeld v. FAIR's point: when you have to explain your symbolic conduct, its not really

symbolic conduct that is protected.

Rumsfeld v. FAIR (2006) p 206, p 387 (expressive association)

Facts: Law Schools challenge the Solomon Amendment as an infringement of expressive

association

Held: This is NOT expression. The Solomon Amendment regulates conduct, not speech.

16

17

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

K.

COMMERCIAL SPEECH/ADVERTISING

Blackletter: p 229

What is commercial speech?

Proposes a Commercial transaction = advertising

Indirectly promotes a product, even if it doesnt offer it for sale (fuzzy line)

What is not commercial speech?

Being sold doesnt make it commercial

Label as Advertisement doesnt make it commercial (NYT v. Sullivan)

Economic motivation doesnt make it commercial (union pay demands)

Less protected that noncommercial speech (four prong Central Hudson test)

(1) False or (2) misleading ads can be punished

o potentially (but not inherently or actually) misleading info cannot be banned if

the info could be presented in a way that is not deceptive. Peel, p 250.

o Disclosures can be required even if theyd be unconstitutional as to noncommercial speech. Zauderer.

(3) Ads concerning unlawful activities can be prohibited (even if advocating those

activities is protected speech, and even if Brandenburg incitement criteria are not met)

(4) Truthful ads for legal activities can be prohibited if government regulation meets a

three-part test (similar to heightened scrutiny) (p 230)

o Restriction justified by a Substantial government interest

Prevent offense is not substantial

Preventing undue pressure on customer is substantial (Ohralik)

Promoting Energy efficiency and fair prices is substantial (Ctrl. Hudson)

o Restriction directly advances that interest

o It is not more extensive than necessary to serve that interest (proportional)

Tailoring prong here is significantly different than in the strict scrutiny context.

Here, identifying a less restrictive speech alternative does not mean that the restriction

fails. The government looks to a Reasonable fit.

Prophylactic rules that may restrict un-harmful speech are okay if its hard to distinguish

which speech will be harmful (Ohralik), but not if you can identify the bad speech up

front (Central Hudson).

Shielding customers from information that would lead to unwise choices?

Per se impermissible? 44 Liquormart (Stevens + 2 plurality, Thomas

Concurrence)

But see Central Hudson: Okay to ban ads that would cause a net increase in

energy usage.

Central Hudson (1980) p 233

Facts: Commission blocks ads intended to stimulate the purchase of utility services.

17

18

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

Analysis: (1) not deceptive or criminal, (2) substantial interest in energy conservation, directly

advanced by blocking ads encouraging energy use. However, might be broad to the extent that it

blocks ads for products that have no effect (or a positive effect) on energy usage.

Concur: Blackmun: Government has no business regulating speech for its effect on the public,

absent clear and present danger. Stevens: Also adopts clear and present danger rationale (go

after the electricity usage, not the advertising). Dissent: Rehnquist: Majority Opinion is Lochner;

cant knock down reasonable regulation of commercial speech (distinguished from political).

Virginia St. Bd. Of Pharmacy (1976) p238

Facts: P challenged a VA law criminalizing publication or advertisement of the price for

prescription drugs by a licensed pharmacist.

Analysis: Speech does not lose protection because money is spent to project it, because it is

economically motivated, because it is carried in a form that is sold, or because it may involve a

solicitation to purchase goods or contribute money.

Held: Ban impermissible. The strength of the argument that aggressive price advertising will

corrode professional standards and relationships is undermined by the states licensing system.

The preferable alternative is to assume people will perceive their own best interests if well

enough informed.

Dissent: Rehnquist argues that this subject is properly the concern of the state legislature. The

difficulty of line-drawing between political and other forms of commentary does not excuse the

blurring of lines between protected non-commercial speech and regulateable commercial speech.

Ohralik (1978) p 243

Upholds ban on solicitation under circumstances where the potential customer is in danger of

fraud, intimidation, undue influence, etc. Inherent

44 Liquormart (1996) p 244

Facts: RI banned ads for liquor and on public display of liquor prices (outside the store).

Analysis: Keeping people in the dark for their own good = bad. Cannot have a blanket ban on

truthful, non-misleading, commercial messages for lawful products, without meeting the Cental

Hudson test; here, the wholesale ban on ads doesnt materially (or substantially) serve the states

interest in reducing alcohol consumption. Court suggests taxes or limiting purchases instead.

Banning speech may sometimes prove far more intrusive than banning conduct.

Thomas, concur: When the asserted interest is to keep people in the dark, it is per se invalid and

the Central Hudson test should not be applied.

18

19

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

L.

STRICT SCRUTINY

Blackletter: p259. Even protected speech can be restricted.

If the speech restriction attacks core speech (not commercial or exceptions), strong

presumption of unconstitutionality. Used for non-excepted speech involving content-based

distinctions

Government as sovereign, attacking speech for its communicative impact.

o Different test for government as employer, subsidizer, speaker, etc.

o Different test when its a content-neutral restriction

Test is very, very difficult to satisfy: Holder is the only one to make the cut so far

The test:

o (1) Compelling government interest (important enough to restrict speech?)

Not Compelling: p 259, 261.f.

Cant favor some protected speech over other (without some other

reason than favoritism) (Carey v. Brown, labor picketing)

Avoiding offense and restricting bad ideas (without more) is not ok

(TX v. Johnson, flag burning)

Underinclusiveness: signal that the interest isnt very important,

(Florida Star v. B.J.F.) or that its not the genuine reason for the

regulation (Carey)

Equalizing relative ability to influence the outcome of elections

(Buckley)

Compelling: p 260.e.

Combating terrorism (Holder, p 281)

Protecting minors from literature that is not obscene by adult

standards (Sable Comm. v. FCC)

Protecting votes from confusion or undue influence (Burson v.

Freeman plurality)

Preventing Vote-Buying (Buckley v. Valeo, p 446)

Protecting minorities right to live where they want in peace (dicta,

R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul, p 295; struck down on tailoring)

o (2) Narrowly Tailored

Regulation must materially advance the interest (persuasive commonsense foundation)

Not overinclusive (cant burden speech that falls outside the interest,

unless its hard to tell the difference; Buckley p 446, But see Schneider v.

NJ p322, overturning littering ban on leafleting)

Not underinclusive

Highly tied to the compelling interest prong

o Government sincerity

o Government accuracy

19

20

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

This could also lead, ironically enough, to greater government

regulation

o Think of Carey v. Brown, which prohibited picketing in

front of residences except for labor protests; this was struck

down largely based on underinclusivitylabor picketing is

just as invasive on privacy as other types of picketing

Least restrictive alternative

Restrict conduct instead of speech; limit speech instead of barring

it altogether

But must be an effective alternative to protect the interest

(Ashcroft v. ACLU II, p 268)

But see Florida Star v. B.J.F. p 264: There really is no less restrictive alternative to

forbidding publication of rape victims names (when the interest is protecting privacy and

encouraging others to come forward); however, Court rejected the argument, holding the

law unconstitutional even though it was necessary to a compelling interest just because

it didnt have an exception for public concern.

Cases:

Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project (2010) p 281

Facts: Crime to knowingly provide material support or resources to a foreign terrorist org. as

defined by Sec. of State. Definition of Material Support includes training, expert advice,

service, and personnel (under direction of the org.); challenged on free speech grounds as

preventing HLP from training these groups on peaceful alternatives to terrorism and political

advocacy.

Analysis: Compelling Interest of the highest order; Congress made a finding that these

organizations are so tainted by their criminal conduct that any contribution to such an

organization facilitates that conduct either through legitimization or fungibility. Court makes

much of the limiting factor that the support must be coordinated with or under the direction of

an org. Also points out that the challenge is pre-enforcement and very general; impossible to say

what are services (e.g. publications in support? Speaking in front of Congress?)

Dissent: Breyer +2. This prevents pure speech (petitioning Congress) and association (in

coordination with), and falls outside of Brandenburg incitement test. Theoretically could ban a

brief by a lawyer hired to represent such a group.

Carey v. Brown (1980) p 455

Facts: Picketing outside residences banned except for labor picketing. Plaintiffs picketed the

Mayors house demanding school integration.

Analysis: showing a preference for one topic of speech is impermissible.

[more cases over]

Ashcroft v. ACLU II (2004) p 268

20

21

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

Facts: Child Online Protection Act imposes penalties for posting (for commercial purposes)

anything that is obscene or violates Miller For Minors. Affirmative defense: website requires

proof of age through technology, etc.

Analysis: Concern about less restrictive alternatives. Filters are just as effective and less speechrestrictive.

Dissent: Chooses a different baseline Majority (is COPA more effective than filters), Dissent

(is COPA more effective than filters alone)?

Florida Star v. B.J.F (1989) p 275

Strict in theory, fatal in fact.

Facts: BJF reports sexual assault; police f- up and put the report (with victim name) in the press

room. Florida Star reporter printed a short article, including the victims name, which violated FS

policy as well as a local law making it unlawful to print the name of a sexual assault victim.

Interest in privacy and encouraging victims to come forward.

Analysis: Emphasis on how FS got the information. (1) government can prevent the publication

simply by preventing dissemination of the protected information. (2) if info is already in the

public domain, you cant punish people for disseminating it. (3) Self-censorship if press could

get in trouble for publishing press releases, reports, etc. (4) underinclusive b/c doesnt go after

small disseminators, just mass communication

Held: Cant prevent publication of the name, because publication was on a matter of public

concern (getting the perp) and they got the info lawfully. Also says that if it becomes a matter of

public concern because of potential fabrication of charges, the info is fair game. (UGH!)

Dissent: p 279 There were signs all over the press room saying that reporters were not to

disseminate the name of rape victims. This basically eliminates the tort of publication of private

facts. Biggest difference from majority: private (not public)

21

22

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

M.

CONTENT DISCRIMINATION WITHIN UNPROTECTED SPEECH

Blackletter: p 292 Even restrictions on unprotected speech can be unconstitutional

R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul: A restriction on unprotected speech must pass strict scrutiny if it

includes a specific content restriction within it, e.g. obscenity that includes flag burning; threats

against the President that mention his economic policy; commercial ads that depict men in a

demeaning fashion.

What is a content-based distinction? You have to know what the speech says to determine if it is

covered by a restriction.

Exceptions:

Virulence: The internal content discrimination if the basis for it is the same reason that

the class of speech is proscribable

o extra prurient obscenity; very threatening threats (e.g. against the President); extra

fraud-prone commercial ads (lawyers, maybe funeral homes)

Secondary effects of the subclass of speech are independently justified without reference

to the speech

o Offense and emotive impact of speech isnt a secondary effect

o Basically, correlation with bad conduct (Renton: adult entertainment attracts

prostitution)

Conduct: If the subclass can be swept up under a law that regulates conduct, not speech

o Sexual harassment law permits a restriction on sexually derogatory fighting

words.

o But see p 358, Holder.

No Suppression of Ideas: If there is no realistic possibility that official suppression of

ideas is afoot

Hate Crimes: Strict Scrutiny only applies to Speech restrictions, not bias-motivated Conduct

(increased penalties for hate crimes).

Cases:

R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul (1992) p 295

Bigoted Speech

Facts: Racially-motivated cross burning punished under a law that prohibits placing a

symbol including a burning cross which one knows arouses anger, alarm, or

resentment in others on the basis of race, color, creed, religion, or gender. MN Sup. Ct. had a

narrowing construction such that only Chaplinsky fighting words were punishable (those

which by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.).

Analysis: Scalia You cant have a content-based restriction within proscribable speech

(exceptions start p297 bottom). This law only punishes fighting words on one of the disfavored

topics (content-based), and only when speaking on one side of the topic (viewpoint-based).

Fighting words is about the Manner of expression, not the content. And though there is a

compelling interest, this speech restriction is not necessary; there are content-neutral

alternatives.

22

23

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

Concurrence: Concur in result b/c the fighting words construction doesnt save causing anger,

alarm, or resentment, which is not proscribable. White +2: Within an unprotected class of (non-)

speech, there is not good reason why a subclass should get protection; this signals that fighting

words and hate speech are a legitimate form of public discussion. White +3: It should survive

strict scrutiny, because there is no less restrictive (albeit content-neutral) alternative; majority

says you cant have a content-based restriction if the objective could be achieved by banning a

wider swath of speech. Would apply Equal Protection review to regulation of unprotected

speech. Also notes that the St. Paul restriction falls into the first exception (for extra-bad threats).

Virginia v. Black (2003) p 303, facts on p 216 (Threats)

Facts: two sets of convicted Defendants under a VA statute criminalizing cross burning with

intent to intimidate (and rebuttable presumption that there was intent): one KKK leader who

burned a big cross with no particular person as a target; other were two boys who burnt a cross to

get back at a black man who complained about their shooting guns for target practice.

Analysis: OConnor - This passes the first exception to RAV, because intent to intimidate is a

subcategory or proscribable threats (extra violent threats).

Dissenting in Part: Souter This is about blocking racist speech, not violence, so doesnt fit into

the extra violent threats exception to RAV. It is content-based. The prima facie provision shows

that official suppression of ideas may be afoot. It doesnt fit the secondary effects exception

either. Thomas this is about conduct, not speech; the ban is on violence (Siamese twin of crossburning).

23

24

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

III.

CONTENT-NEUTRAL RESTRICTIONS

A

RESTRICTIONS ON SPEECH & EXPRESSIVE CONDUCT

Blackletter: p 319

What is expressive conduct / symbolic speech? p 205 (if it needs an explanation, probably not

expressive enough to be considered speech. Rumsfeld v. FAIR)

OBrien Test: a government regulation is sufficiently justified . . . if it furthers an important or

substantial government interest; if the governmental interest is unrelated to the suppression of

free expression; and if the incidental restriction on alleged First Amendment freedoms is no

greater than is essential to the furtherance of that interest.

Time, Place, and Manner restrictions on speech & limits on expressive conduct are okay if

(1) justified for non-content reasons, and may limit expressive conduct (symbolic

speech) for its non-communicative impact. (loud, littering, traffic, fires)

(2) Substantial government interest

o Less than compelling. Residential privacy counts (Frisby).

(3) Narrowly tailored to serve this interest

o Less than is required under strict scrutiny (can be underinclusive, doesnt need to

be the least restrictive means)

o Removing the restriction or exempting the conduct would materially interfere

with the government interest (Clark v. CCNV)

o Cant be overinclusive (cant burden speech that doesnt implicate the

governments interest)

o Burden must be proportionate to the threat to the government interest (Schneider)

(4) Leave open ample alternative channels for communicating the information.

o Basically measures the burden on speech

o Suggested Alternative Channel fails if it is: (see City of Ladue)

Too expensive

Unlikely to reach the same audience

Likely to carry a different implicit message from the suggested alternate

time, place, or manner

o If it doesnt leave open ample alternative channels, apply strict scrutiny.

o May not apply when its a restriction on conduct (but there is always an

alternative to conduct --- speech! OBrien, Harlan concurrence)

What is Content Neutral? P 337

Cases:

Schneider v. NJ (1939) p 322

Facts: People with a right to be where they were, and only giving leaflets to willing recipients,

were convicted under laws prohibiting leafletting because it leads indirectly to littering.

Analysis: Keeping the streets looking good is not a substantial government interest; even if it

were, the ban is disproportionate, and removing the restriction wouldnt materially interfere with

the governments interest, because they could still punish people who actually litter.

24

25

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

Frisby v. Schultz (1988) p 323

Facts: peaceful, quiet anti-abortion protesters picketed the home of a doctor who performs

abortions. Town enacts a provision making it unlawful to picket an individuals residence.

Analysis: Content Neutral, yes. Ample alternatives? Yes, can walk through a neighborhood, make

phonecalls, etc. Significant government interest? Yes, sanctity of the home and protection of the

unwilling listener in his home (think FCC v. Facifica, as opposed to in-public, Cohen). Narrowly

tailored? Yes. Only limits targeted picketing of homes, which is inherently intrusive, and where

the resident is presumptively unwilling to hear it.

Dissent: Brennan, Marshall Intrusiveness is not inherent, and the speech is to the public, not

just the resident. Not narrowly tailored, because it limits more than coercive or intrusive conduct

(could limit the number of protestors, the hours, and the noise).

City of Ladue v. Gilleo (1994) p327

Facts: Sign in window advocating peace in the Gulf; prohibited under an ordinance that bans

signs in residential areas.

Analysis: Not compelling; no meaningful alternatives; overbroad. The govt interest in reducing

visual clutter is valid, but not especially compelling. In contrast, the ban has almost completely

foreclosed a unique and important means of communication. Although prohibitions foreclosing

entire media may be free of content or viewpoint discrimination, they pose the danger of

eliminating too much speech. Here, there are not adequate alternatives preserved; residential

signs, precisely by their location, provide information about the identity of the speaker, which is

an important component of attempts to persuade. Moreover, they are a low-cost form of

communication which may not have cheap and practical substitute, eliminating speech by those

of limited means or mobility; in addition, their placement may be linked to a desired audience of

neighbors. Finally, residents self-interest in governing visual clutter diminishes the need for

govt involvement.

US v. OBrien (1968) p328

Facts: D burns his draft card at a public demonstration, and is convicted under a statute

prohibiting knowing destruction or mutilation of same.

Analysis: a government regulation is sufficiently justified . . . if it furthers an important or

substantial government interest; if the governmental interest is unrelated to the suppression of

free expression; and if the incidental restriction on alleged First Amendment freedoms is no

greater than is essential to the furtherance of that interest. Draft cards serve the govt interest in

raising armies, facilitating communication, and reminding registrants of their draft obligations,

all of which would be impaired by their destruction. The ban directly targets only conduct

endangering the govt interest; this is not a case in which the interest in regulating conduct arises

because communication integral to the conduct is found harmful. Legislative history

notwithstanding, the motives of Congress or the measures sponsors is not relevant in

determining the intent of the statute for First Amendment purposes.

Concur: Harlan - this rule may not apply where incidental regulation may entirely prevent a

speaker from reaching a significant audience.

[more cases over]

25

26

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

Clark v. Community for Creative Non-Violence (1984) p331

Facts: The National Park Service issued a permit to erect symbolic tent cities in the Mall, but

denied the request that people be allowed to sleep there overnight (not a camping area).

Analysis: NPS could ban 24-hr vigils and tents altogether to protect the park (legitimate

interest); by allowing the protest, they arent foregoing the right to prevent sleeping, even if it

would hinder the protest. Doesnt matter if there is a less speech-restrictive alternative.

Dissent: Majority failed to examine whether the ban actually furthers the governments interest.

Notes that the ban is underinclusive it permits feigned sleep, which probably has the exact

same detrimental effect.

26

27

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

IV.

SPECIAL BURDENS ON FREE SPEECH

A

FORCED ASSOCIATION

Blackletter: p 359

We have a right to associate for expressive purposes (broader than the right to assembly). Not the

same as intimate association (smaller groups).

Usually, requirements that an expressive association accept unwanted members or voters, if it

substantially interferes with the organizations ability to convey its message, would be reviewed

under strict scrutiny:

(1) Substantial burden? Compare Boy Scouts (yes, substantial burden to permit gay

scoutmasters) to Jaycees (not substantial burden to admit women as full members)

(2) compelling government interest? (ending discrimination Jaycees)

(3) narrowly tailored? See Strict Scrutiny section.

o But see Boy Scouts: neglected to apply strict scrutiny after finding that admitting

gay scoutmasters would be a substantial burden; never looked at government

interest or narrow tailoring.

Note: commercial associations may be different. See OConnor concurrence in Jaycees.

Cases:

California Democratic Party v. Jones (2000) p364

Facts: California has a partisan blanket primary where anyone can choose the partys candidate

(contrast with a non-partisan blanket primary, where voters are not choosing the partys nominee,

but are simply picking the top two favorites among all candidates).

Analysis: Huge burden on a partys associational freedom; doesnt survive strict scrutiny (not

narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest). Compelling interest in including non-party

members in primaries is no good they can simply join the party. Dissent p 369 questions the

courts choice of what makes democracy work by siding with autonomous parties, versus

including the entire electorate. Parties are state institutions once they go into elections.

Roberts v. Jaycees (1984) p 372

Facts: Jaycees will not admit women as full members, though they are allowed to participate in

some activities. Jaycees offers networking, business training, and political training. Violates MN

law of organizational discrimination.

Analysis: Substantial Burden on message to admit women? No (therefore, burden of strict

scrutiny does not switch to the government). The right to not associate / to choose with whom to

associate is protected, but eradicating gender discrimination is a compelling interest. Here, that

interest is furthered in the least restrictive manner possible. Jaycees only make unsupported

generalizations about how women change the message, and the court doesnt buy it.

Concur: OConnor rejects the member-message test; only question is whether the association

exists predominantly to engage in protected expression (if so, message and members are

protected). Includes activities engaged in for educational purposes (Boy Scouts). Characterizes

Jaycees as a commercial association (eee to eer, shopkeeper to customer), so can be proscribed.

27

28

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

Boy Scouts v. Dale (2000) p 377

Facts: Superstar boy scout comes out in college and engages in some gay rights activism

(interviews). Boy Scouts revoked his membership in the Scouts and would not allow him to be a

scoutmaster. NJ Sup. Ct. ruled that the Boy Scouts are a public accommodation.

Analysis: Relies on Hurley. It seems indisputable that an association that seeks to transmit such

a system of values engages in expressive association. Forced inclusion of Dale would

significantly burden the orgs right to oppose or disfavor homosexual conduct b/c anti-gay

views are sincere and we must give deference to an associations view of what would impair

its expression. (conflicts with Jaycees). Also says it doesnt matter whether they tolerate dissent

in the ranks, because a gay scoutmaster sends a different message than a straight scoutmaster

who loudly disagrees.

Dissent: Stevens +3: No serious burden, and no compelled speech. Exactly like Jaycees (simply

adopted a discriminatory policy, and has no shared goal of expressing views on sexuality at all);

look to whether excluding [gay people] would impose a serious burden on their ability to engage

in protected speech or reach their basic goals. The law doesnt require them to change

ANYthing. Compare to Hurley: unlike GLIB, Dale has no intention to carry a message about

homosexuality; he is not affixed with a label that makes him forever excludable under the First

Amendment.

Rumsfeld v. FAIR (2006) p 387, facts p 206

Facts: law schools refuse to allow military recruiters; claim first amendment freedom of

expressive association.

Held: Allowing recruiters on campus is not expression; it doesnt violate association either,

because students and faculty can still protest the presence of the military, and the statute does not

make membership in the [law school] less attractive (where did they get this idea? Wouldnt

LGBT students and allies be less likely to go to a school that allowed discriminatory recruiting

practices on campus?)

28

29

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

N.

SPEECH-RELATED SPENDING & CONTRIBUTIONS

Blackletter: p 445-59, 468-96

Money is not speech, but it enables speech. A restriction on money-used-for-speech is thus a

restriction on speech and must pass [heightened?] scrutiny.

Rules:

Content-based restrictions on expenditures, i.e. spending money to speak (independent of

political candidates or parties), must pass strict scrutiny. Citizens United, Bellotti.

o Includes union, corporate, non-profit and individual spending

o Political non-profits speech/money is usually considered protected even by those

who would allow restrictions on election speech by unions and corporations.

o ** Restrictions on Independent Expenditures fail strict scrutiny. Citizens United,

Buckley.

Restrictions on contributions to candidates and parties must pass heightened scrutiny.

o Government interest in avoiding corruption and the appearance of corruption

permits a $1000 cap on individual contributions (narrowly tailored)

But a later case (Randall v. Sorrell) said $400/pp was too little.

Restrictions on expenditures in coordination with a candidate is the same as a

contribution to the candidate.

Themes:

Expenditure does NOT equal contribution.

o Contributions dont have as much expressive quality

Legitimate interests:

o Level the playing field is not a legitimate interest; favors some speech more

than others.

o Preventing corruption (quid pro quo) & appearance of it is legitimate.

First Amendment values?

o Neutrality? but you always start out somewhere, and the default isnt neutral.

o Marketplace? But big voices drown others out

o Democratic process? But this distorts democracy and principle of free elections

o Self-expression? Only for the super rich; others get drowned out.

o Whatever happened to one-person, one-vote?

Cases:

Buckley v. Valeo (1976) p 446 Analysis: per curiam

Upholds law placing a cap on contributions to candidates, because it helps reduce the appearance

of corruption.

Strikes down law limiting individual expenditures; first, saying it only applies to advocating

election or defeat of a candidate (for vagueness), and then saying that the appearance of

corruption doesnt justify a limit on this particular construction, because orgs are not prevented

from campaigning a LOT to help an unnamed candidate, and there is little chance of quid pro

quo corruption.

Strikes down ceiling on campaign expenditures. Equalizing financial resources is not a legit goal.

29

30

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

Strikes down ceiling on individual expenditures by candidates and their family.

Dissent: White - Agreed with upholding contribution limits; dissent as to individual

expenditures; they are the same. Campaign expenditure limits would help candidates free up time

for actual communication, and restore faith that elections arent for sale to the highest bidder.

[see also dissent in Randall v. Sorrell (2006), which equates these limits with time/place/manner

restrictions, not content-based restrictions.] Marshall dissents just as to individual expenditures,

because a restriction combats the idea that only rich candidates can enter politics.

First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti (1978) p 459

{didnt read for class}

Citizens United v. FEC (2010) p 468

Facts: CU produced a film called Hillary that was really negative toward her campaign. BCRA

prohibited corporations (incl. non-profit advocacy corps) and unions from using general treasury

funds referring to a particular candidate within 30 days of a primary or 60 days of a general

election. There is a PAC exemption, with money limited to donations of employees,

stockholders, and union members.

Analysis: six parts, see p 468.

(1) Corporate Status: The PAC exemption does not allow corporations to speak as their own

entity, and they are burdensome to run. Speech restrictions based on the identity of the speaker

are all too often simply a means to control content.

Dissent: This is not a Ban. PACs and MCFL organizations (see p 242-43) are viable alternatives

allowing individuals associated with corporations to speak out; it doesnt apply to books or noncandidate related material (so issue advertising is safe). And we CAN distinguish between

speakers based on their identity, p 476, such as limiting campaign contributions from foreigners,

and preventing government employees from engaging in certain political activities, and

preventing corporations from voting. Some companies actually WANT limits on contributions to

avoid a shake down.

(2) Media Corps: p 482 Anti-distortion rationale would allow rich media corps to be limited.

Dissent: Media is special, and identity of the speaker does matter we can provide an

exemption.

(3) Corruption: p 483, agrees with Buckley that independent expenditures cause corruption;

Scalia notes that these rules help incumbents. Dissent p 485

(4) Original Meaning: p 489-90 Concurrence: Associational speech was okay under the

founding, and the text has no limits on which kind of speakers get rights. Dissent: Founders

hated Corps, and, other than media (freedom of the press), can be regulated.

30

31

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

O.

SPEECH COMPULSIONS: DIRECT INTERFERENCE W/SPEAKERS OTHER SPEECH

Blackletter: p 496-520

Compelled speech is bad because:

(1) A speakers message can be changed by the speech it is forced to accommodate

(Rumsfeld v. FAIR; Hurley v. Irish-American GLB Group)

o Requiring a newspaper to print something will change the content because:

It now has the new content

The new content replaced something else

News may be deterred from publishing certain things if that will require

space to be made for a reply (Miami Herald)

(2) Required speech violates the freedom to choose what to say, if anything.

o Requiring a child to say the pledge (Barnette)

o Requiring display of a message on a license plate (Wooley)

(3) Requiring payments that will be used for speech may interfere with right to expressive

association (i.e. he will be associated with the speech by paying for it). Detroit Bd. Of

Ed., Keller v. State Bar.

(1) When a speech compulsion interferes with the speakers message, its presumptively

unconstitutional.

Triggered by the content of the speakers message (Miami Herald). Content-based

penalty (Turner Broadcasting) = restriction and compusion.

Interferes with coherent product (common theme or editorial voice). Hurley, Miami

Herald, Riley, maybe PG&E.

The compulsion makes the burdened party feel pressure to respond or disavow the

message. (see p 498. Less strong in precedent.)

(2) When the compulsion doesnt stop you from expressing your own views: see below.

(3) Forced contributions are unconstitutional, except: {Didnt Read This Section}

When they pass strict scrutiny (but money must be used for purposes germane to the

reason for the compulsion, and nothing more broad). Abood (union dues to prevent

strikes through collective bargaining), Keller (bar dues for attorney discipline).

To a university student government, when it will be spent in viewpoint neutral ways

To the government for the governments own speech. Explanation, p 499 - 500.

Cases:

Miami Herald v. Tornillo (1974) p 503

Facts: law required newspapers to give a right to reply to people attacked by newspapers

Held: Court strikes this down both because it forces the newspaper to use its resources for

someone elses speech, and because being forced to carry their adversaries may chill newspapers

against speaking in the first place. Not only can states not censor speech to encourage equality

(Buckley), but they cannot force people to speak.

31

32

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

Riley v. Nat. Federation of the Blind (1988) p 505

Facts: Professional fundraisers have to disclose the percentage of the money they raise that goes

to the charity.

Held: This is a content-based regulation. State interest: ensure public is informed to prevent

fraud. But donors already realize solicitors incur costs. This law disfavors professional

fundraisers. Other, more narrowly tailored options exists: State could publish this information

itself; state could enforce its antifraud laws. It also prevents people from giving the message they

want to present.

PG&E (1986) p 508

Facts: Utility commission required utility to allow TURN, an advocates group, access to its

billing envelopes for speech purposes.

Held: Discriminates against who may access the envelopes (The order awarding access

discriminated on the basis of viewpoint in selecting speakers; two of its purposes were to provide

a greater variety of views and to assist intervenor groups to raise funds; such one-sidedness

impermissibly burdens Ps own expression). Burdens the utilitys expression, b/c forces utility to

respond or tacitly approve the speech (Because access is only awarded to those who disagree

with P, whenever P speaks on a given issue, it may be forced at anothers discretion to help

disseminate hostile views. Under these circumstances, P may conclude the safe course is

silence). Would be constitutional for California to tax utilities and use that money to send the

TURN message because that would not risk confusing it with the utilitys message or force the

utility to respond.

Turner Broadcasting (1994) p 514

Facts: P challenges statute requiring cable systems to carry local commercial and public

television stations operating in the same market as the cable system without charging a fee for

carriage.

Held: Constitutional. Viewers understand that cable companies do not send messages via their

content. They are really just conduits for messages. Unlike the access rules in Tornillo and

PG&E, the cable must-carry rules are content-neutral; they are not activated by any particular

message spoken by cable operators, exact no content-based penalty, and do not grant access to

broadcasters to counterbalance cable operators messages. Thus, cable operators will not be

required to alter their messages in response to the broadcast signals and no aspect of the rule

would lead to the conclusion that the safe course is silence. Moreover, unlike a newspaper, cable

operators exercise de facto control over access to the medium and can silence the voice of

competing speakers; the potential for abuse in this situation need not be ignored. The

requirement that govt not impede the freedom of speech does not disable it from taking steps to

ensure that private interests do not restrict the free flow of information or ideas by virtue of their

physical or market position.

[more cases over]

32

33

H. Warden First Amendment Prof. Benjamin Fall 2011

Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian and Bi. Grp. (1995) p 515

Facts: GLIB P sues private organizers of traditional parade, alleging violations of state public

accommodations law based on sexual orientation. D appeals, arguing that forcing Ps admission

would violate their First Am rights of expressive association.

Held: Hurley does not need to include the group. Parades are expressive and inclusion of groups

will likely be attributed to the organizers. Since every participating unit affects the overall