Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Sela Antenna in The Eeuu No 113 July 2015

Cargado por

Daniel GilTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Sela Antenna in The Eeuu No 113 July 2015

Cargado por

Daniel GilCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

SELA Antenna in the United States

SELA Permanent Secretary

N 113 July 2015

SUMMARY: IMPACT OF THE TRANSPACIFIC PARTNERSHIP ON ITS MEMBERS, THE REGION, AND THE WORLD Will the

Agreement Be Concluded and Approved? - How Much Trade Will the Agreement Create, and How Much Will It Divert?

Can the TPP and Other RTAs Provide a Substitute for the Multilateral System?

Impact of the TransPacific Partnership on Its Members, the Region, and the World

The talks over a TransPacific Partnership (TPP) may produce the most consequential trade agreement thus far in the 21st

century, affecting not just the dozen countries that are participating in this megaregional negotiation including Chile,

Mexico, and Peru but also the rest of the region and the world as a whole. In addition to covering a large share of the

trade in the Pacific Basin, and affecting the competitive positions of both participants and non-participants, the TPP could

also have direct and indirect effects on other regional and multilateral trade negotiations.

The TPP negotiations have been underway in one guise or another since 2005, having started as a relatively modest initiative

bringing together Chile, Brunei, New Zealand, and Singapore. The scope of the negotiations expanded greatly when the

worlds largest economy (the United States) joined in 2008, followed by the third-largest (Japan) in 2013. Others that came

to the table during 2008-2013 include two more developed countries (Australia and Canada) and four developing countries in

Latin America (Mexico and Peru) and Asia (Malaysia and Vietnam). The TPP could grow larger still, with the three Latin

American and Caribbean (LAC) countries that are most frequently mentioned as candidates being Colombia, Costa Rica, and

Panama. Other economies that might also join the talks include Korea, the Philippines, and Taiwan. China is sometimes

mentioned as a potential TPP participant but, as discussed at greater length below, that is a matter on which current TPP

countries hold decidedly different views.

This note examines the prospects for the TPP and its potential impact on SELA Member Countries, both those that are and

those that are not members of this regional trade arrangement (RTA). The significance of the TPP can be seen at two distinct

levels. One concerns its immediate impact on the economic interests of individual countries, as the agreement may benefit its

participants by creating new trade but may also cause some harm to third parties by diverting trade. Viewed at a higher level

of abstraction, the negotiation of the TPP may also influence the direction of the global trading system. The bargains that are

struck in the TPP might set precedents that spread to other countries, whether through the accession of those countries to

the TPP, the emulation of those rules in other RTAs, or their incorporation into the rules of the World Trade Organization

(WTO). Together with a series of other megaregional negotiations in which the largest economies are pairing up with one

another, however, the TPP also casts doubt on the future of a multilateral trading system in which the WTO is the

centerpiece and non-discrimination is valued as highly as liberalization.

It is important to stress from the outset that there remain a great many unknowns regarding the content of the TPP, the

environment in which it will be concluded and made subject to domestic approval, and its impact on participating and third

countries. As discussed below, some of the most significant missing elements are uncertainty over whether the agreement

will come up for consideration in the U.S. Congress during the final months of the Obama administration or in the early days

of the next president, what the impact of the agreement may be on participating and third countries, whether the trading

system will treat the TPP and other megaregional agreements as complements or substitutes for multilateral liberalization,

and how this agreement will affect the place of China in that system. It is beyond the scope of this note to resolve those

unknowns, but the analysis does seek to place each of these questions in context.

Will the Agreement Be Concluded and Approved?

Before assessing the impact that the TPP may have on the trading system in general and specific countries in particular, one

must first ask whether the agreement will ultimately be concluded and implemented. While this question may sound

pessimistic, recent history suggests that it is realistic: The mortality rate for trade agreements has been remarkably high in

the two decades since the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations concluded in 1995.

SELA Permanent Secretariat, Apartado Postal 17035, El Conde, Caracas 1010-A, Venezuela

Tel: 955.7111 / 955.7121 Telefax: 951.5292 / 951.6901 E-mail: difusion@sela.org http://www.sela.org

(Legal Deposit No. pp 199603CS182, ISSN: 1317-1836)

SELA Antenna in the United States

N 113 July 2015

One may cite a long list of negotiations that collapsed either because of developments in the domestic politics of one of the

participants or a failure of the negotiators to resolve their differences. The ill-fated Free Trade Area of the Americas is the

most prominent example in the Western Hemisphere, but other bilateral and subregional talks in the Americas have also

failed (e.g., between Ecuador and the United States). Among the other negotiations that have either fragmented or imploded

over the past two decades are the free trade pact planned in the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation forum and the

Multilateral Agreement on Investment that was attempted within the Organization for economic Cooperation and

Development. And unless countries manage to revive it, the Doha Round in the WTO which has now missed the original

2005 deadline by a full decade could also join the list of failed negotiations.

There have also been notable agreements that were concluded at the international level, but then either failed altogether in

the domestic ratification process or faced much deeper and prolonged opposition than had been anticipated. The AntiCounterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA), for example, was supposed to provide for stricter standards than the WTOs

Agreement on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights. Mexico was among the ten signatories to that pact, but ACTA died

after the European Parliament voted it down in 2012. While that episode demonstrated that the European Parliament is

becoming more active in its review of trade negotiations, it is the U.S. Congress that has traditionally been most prone to

question and, in some cases, undo the work of the countrys negotiators. The hurdles that Congress places in the way of

trade agreements have grown even higher now that they are scrutinized not only for their commercial implications but also

for their connection to other issues. The domestic politics of U.S. trade policy have increasingly come to be dominated by the

association of trade with divisive topics such as labor rights abroad, the distribution of income at home, and environmental

protection everywhere.

Congress could pose the biggest obstacle to the approval and implementation of the TPP. This legislative body once again

demonstrated its skeptical view of trade agreements in June, when it narrowly approved a new grant of trade promotion

authority (TPA) for President Obama. The TPA, also known as the fast track, is an indispensable tool for any serious trade

negotiation in which the United States is involved, as it establishes special rules that prevent Congress from either killing an

agreement through dilatory maneuvers or amending it beyond recognition. These rules do not prevent all efforts by Congress

to influence how an agreement is negotiated or translated into national law, and there have been some notable instances in

which legislators have manipulated the TPA rules in order to force changes in agreements; this was especially notable in the

debates over the U.S. free trade agreements (FTAs) with Colombia, Mexico, Panama, and Peru. The track record of the TPA

has nevertheless been very positive: Every trade agreement that presidents have submitted to Congress under the terms of

the TPA have ultimately been approved, even if some of them encountered significant challenges along the way.

President Obama signed into law on June 29 the newest grant of TPA. The Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and

Accountability Act of 2015 will last not only though the rest of President Obamas term but also more than one year into the

term of the next president (i.e., until mid-2018). The law also provides for another three years of authority (i.e., until mid2021) if the next president asks for this authority and the Congress does not reject his request. There are two possible ways

to interpret this most recent congressional debate over trade and its outcome. On the one hand, it is true that in the end

Congress granted the presidents request for new authority, thus ensuring that the TPP negotiators may now enter the endgame of the talks. On the other hand, this is one of the narrowest margins by which a grant of negotiating authority has ever

been made. The final vote for the bill in the House of Representatives was 218 to 208, and only 28 of the 188 Democrats in

the House voted for the bill. The conduct of this internal negotiation revealed that in the short term President Obamas ability

to sway members of his own party is greatly diminished, and that in the long term the partisan divide over trade policy is

becoming ever wider.

How will a final TPP agreement be received in Congress? The answer depends on several as-yet unknown factors, including

the final terms of the agreement and the timeframe in which it is concluded. It is especially important to know whether the

debate over ratification of the agreement will take place in the waning months of the Obama administration or if it will

instead be postponed until after a new president is inaugurated in January, 2017. If this debate happens in 2016 it will come

when the president is a lame duck (i.e., an incumbent whose term is about to end), and hence has less leverage than at

any time of his presidency. If this task falls to the next president, much will depend on whether that chief executive enjoys

the benefits of unified government or, as is presently the case for President Obama, must contend with a Congress in which

the opposition party holds majorities in both chambers.

There is also evidence to suggest that popular support for the TPP in particular is quite thin in the United States, especially

by comparison with other countries that are participating in the negotiations. The data in Figure 1 show that the United

States is one of only two TPP countries in which less than half of the public has a favorable impression of the initiative; by

contrast, the TPP is considerably more popular in Chile, Mexico, and Peru.

SELA Antenna in the United States

N 113 July 2015

No matter when Congress takes up the TPP, it can be anticipated that much of its attention will be focused on how the

agreement affects U.S. relations with just two of the TPP partners. Some U.S. policymakers see the TPP primarily as an RTA

with Japan and Vietnam. All of the other countries in the talks are either partners with which the United States already has

FTAs in effect (i.e., Chile, Mexico, Peru, Australia, Canada, and Singapore), or for which most trade is already duty-free under

other agreements and programs (i.e., Malaysia), or are relatively small markets (i.e., Brunei and New Zealand). This means

that the economic issues in the ratification debate are likely to focus on high-profile sectors in trade with those two countries,

especially automotive trade with Japan, trade in textiles and apparel with Vietnam, and agricultural trade with both countries.

How Much Trade Will the Agreement Create, and How Much Will It Divert?

Assuming that the TPP negotiations are concluded and its results are approved, the next question is what impact they might

have on trade among the groups members and with outsiders. Any assessment of the TPPs impact must start by

distinguishing between the participants in this initiative and third countries. As a general rule, discriminatory trade

agreements will both create some new trade and divert some existing trade. The new trade that an RTA creates will typically

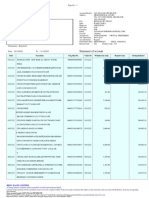

Figure 1: Public Perceptions of the TPP in Selected Countries

Question: Pollsters told respondents that their country is negotiating a free-trade agreement the United States and other

Asian-Pacific countries called the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and asked whether they thought this trade agreement would be

a good thing for our country or a bad thing?

Source: Pew poll at http://www.pewglobal.org/files/2015/06/Balance-of-Power-Report-TOPLINE-FOR-RELEASE-June-232015.pdf, Question 20a. Note that the poll did not include Brunei, New Zealand, or Singapore.

Come from the removal of protection that had provided an artificial advantage to comparatively inefficient domestic

producers; the agreement should stimulate imports from more efficient producers located in the partner countries. This is to

be distinguished from trade that is merely diverted from third countries. Producers in those countries may be more efficient

than their competitors in the partner countries, but that fact may be disguised by the artificial price-competitiveness that is

now extended to partner countries by preferential tariff treatment. As a general rule, it is the partner countries in an RTA

that enjoy both the efficient gains from trade creation and the less efficient gains from trade diversion, but it is producer s in

third countries that tend to suffer the losses from trade diversion.

These third-country concerns are especially high in the case of megaregional negotiations such as the TPP. Those countries

that currently engage in non-preferential trade with the TPP countries will continue to pay tariffs on products that the TPP

countries will now trade duty-free with one another, and those countries that currently enjoy preferential access to the TPP

SELA Antenna in the United States

N 113 July 2015

markets will experience dilution of their preferences. The main questions then become (1) how much trade might actually be

created by the TPP, (2) how large might the gains from trade creation be for the TPP partners, and (3) which countries might

be most seriously affected by the resulting trade diversion?

These are eminently proper questions for economic forecasters to address, but there are as yet only a few publicly available

studies that seek to quantify the trade-creating and trade-diverting effects of the TPP. Moreover, those analyses that are

available generally do not deal with the specific interests of either the participating or non-participating countries in the LAC

region. Most such studies tend either to focus on the interests of large countries, whether they are in the negotiations (e.g.,

Japan or the United States) or outside them (e.g., China or the European Union), or are narrowly focused on specific sectors

(e.g., agriculture) or even subsectors (e.g., livestock). Other analyses are out of date. For example, one study 1 that was

conducted in 2011 and therefore did not yet include Japan as a TPP country found that by 2025 the TPP would increase

GDP in all of the TPP countries, and that the gains would be relatively large for Chile (0.78%), Mexico (0.59%), and

especially Peru (2.12%). The projected gains may presumably be higher now that the TPP has expanded. That study also

calculated the impact on non-TPP countries, some of which would experience gains while others would suffer losses, but did

not provide specific estimates for any LAC countries other than these three TPP participants.

The data illustrated in Table 1 offer another way to approach one-half of the equation, at least in a very rough fashion. As a

very general rule, we may assume that the prospects for trade creation among the TPP countries will depend in the first

instance on whether the agreement makes a major change in the tariff treatment between any given pair of countries. If

Country A already has an RTA in place with Country B, we may safely assume that the TPP will make little difference in their

access to one anothers market; conversely, the potential impact of the TPP may be assumed to be greater in the case of

those countries that have thus far conducted their trade on a non-preferential basis. As can be appreciated from the data

illustrated in the table, each of the three LAC countries that are currently in the TPP talks already enjoy RTA relations with

several of the other participants. It is especially notable that all three of them are already RTA partners with Canada, Japan,

and the United States.

All of this implies that the potential value of the agreement for its LAC participants may be limited. Ironically it is Chile one

of the original proponents of the negotiations for which the TPP would appear likely to have the least impact. Chile already

enjoys RTA relations with all eleven of the other TPP countries. The potential gains are somewhat greater for Mexico and

Peru, for which the agreement would cover five or six additional partners, and also for the three other LAC countries that are

often mentioned as potential TPP participants. In none of these cases, however, would the agreement appear to represent a

radically new addition to the existing level of preferential market access.

None of this tells us anything about the level of trade that might be diverted under the TPP, however, nor which third

countries and sectors might be most heavily affected. One can only say in general terms that the impact on any given

country is likely to be higher to the extent that (1) it currently exports significant quantities of goods to TPP countries, (2)

those goods are subject to relatively high and non-preferential tariffs, and (3) there are competing producers of those goods

among the other TPP countries that are also subject to those tariffs, but will henceforth enjoy duty-free access as a result of

the agreement. The impact of the agreement will likely be smaller, but still appreciable, for those countries that already enjoy

preferential access to major TPP countries by reason of existing RTAs or programs (e.g., the Generalized System of

Preferences); in this case the effect of the TPP could be to dilute the value of their preferential access, rather than to place

them at an absolute disadvantage. Either way, and given the diversity of the countries engaged in the TPP negotiations,

there could be a very heterogeneous array of goods that might meet those descriptions.

Table 1: Existing and Prospective Trade Agreements between TPP Countries

Current TPP Countries in Region

Current LAC/TPP

Chile

Mexico

Peru

Potential TPP Countries in Region

Chile

Mexico

Peru

Colombia

Costa Rica

Panama

1

Peter Petri, Michael Plummer, and Fan Zhai, The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Asia-Pacific Integration: A Quantitative Assessment East-West

Center

Working

Papers

No.

119

(2011),

available

on-line

at

http://www.usitc.gov/research_and_analysis/documents/petri-plummerzhai%20EWC%20TPP%20WP%20oct11.pdf.

SELA Antenna in the United States

N 113 July 2015

5

Current TPP Countries in Region

Potential TPP Countries in Region

Chile

Mexico

Peru

Colombia

Costa Rica

Panama

Potential LAC/TPP

Colombia

Costa Rica

Panama

Other TPP

Australia

Brunei

Canada

Japan

Malaysia

New Zealand

Singapore

United States

Vietnam

Key:

= RTA currently in effect

= RTA currently under negotiation

= Own country

Source: Tabulated from data in the WTOs Regional Trade Agreements Information System at.

http://rtais.wto.org/UI/PublicMaintainRTAHome.aspx.

Will the Agreement Set a Template for Future Negotiations?

The TPP is not being negotiated in isolation but is instead one of several megaregional negotiations that are now underway.

These include, among others, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the European Union and

the United States. From the perspective of the trading system as a whole, the most significant question is whether these

megaregional will serve as complements or substitutes for the WTO. They could be complementary if they provide templates

for new agreements that might be adopted by the WTO membership as a whole, or at least by a critical mass of those

members (e.g., in plurilateral agreements under the WTO umbrella). They could instead prove to be substitutes if there is no

further progress in the Doha Round, nor in any other WTO negotiations, and countries opt instead to conduct their

negotiations exclusively by way of RTAs. Either way, the substantive content of the TPP and/or the TTIP could be transferred

to other countries, whether through their accession to these agreements or through the negotiation of new RTAs that are

based on these templates.

This question can be examined in depth when the contents of the TPP and the TTIP are known, but neither negotiation has

reached the stage in which the participating countries are prepared to divulge their contents. To the contrary, the TPP in

particular has been negotiated behind doors that are closed especially tight. The extent of the secrecy surrounding these

negotiations has worked to the advantage of their opponents, who have been able to exploit fears that the talks constitute a

secretive effort to promote the interests of corporations over consumers and citizens. The hacking group WikiLeaks managed

to obtain and post copies of draft chapters dealing with intellectual property rights, an environment chapter text and Working

Group Chairs Report, and other documents, and the group announced on June 2 that it is hoping to crowd-source the

funding needed to provide a $100,000 reward for the leaking of other TPP chapters.

For want of more specific information on the actual content of the TPP agreement, we may instead consider here the general

pattern by which one trade agreement may set precedents for others, and the more specific place of the TPP in this process.

There is a long tradition in which the most influential members of the trading system use RTAs as part of their strategy to

introduce new issues to the trading system and, once they are on the table, to expand upon the commitments that countries

are prepared to make on these topics. The classic example dates from the Uruguay Round of multilateral negotiations (19861994), in which the United States used regional negotiations first with Canada (1986-1988) and then with both Canada and

Mexico (1991-1994) in order to promote what were then called the new issues of investment, services, and intellectual

property rights. The first step in that direction actually came in the negotiation of a U.S.-Israeli FTA in 1985, which was the

first U.S. foray into RTAs, but that agreement covered little trade and was more symbolic than substantive. The U.S.-Canada

SELA Antenna in the United States

N 113 July 2015

agreement was much more significant insofar as it covered the largest bilateral trade relationship in the world, the

precedents that it set on these issues were much more detailed, and the threat that it posed to other countries was far

greater. That threat was simple: If other countries were not prepared to negotiate on these issues in the Uruguay Round the

United States was prepared instead to negotiate solely on a bilateral or regional basis. That threat worked, as the precedents

set first by the U.S.-Canada FTA and then by the North American FTA (NAFTA) helped to shape the environment for, and the

substantive provisions of, the Uruguay Round agreements.

Since the end of the Uruguay Round the United States and the European Union have approached the relationship between

RTAs and the multilateral system in two ways. One is to treat RTAs as a means of obtaining deeper commitments from

countries than they were willing to make in that round, or in subsequent negotiations in the WTO, by exchanging those

commitment for free access to the E.U. and U.S. markets. This allowed them to correct for what Brussels and Washington

saw as the shortcomings of the Uruguay Round agreements, which granted what the United States sought in principle but

did not go as far as the U.S. negotiators had wanted in substance. That dissatisfaction was based either on the general terms

of an agreement, especially those that (in the U.S. view) provided for too many loopholes or ambiguities, or on the specific

commitments that individual WTO members make in their schedules. An example of the first type would be the Agreement

on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs), the rules of which were not as strict as the United States

would have liked, while the commitments that many countries made in the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)

offer a good example of the latter type of concern. In either case, RTAs offer the United States and the European Union a

second chance to pursue deeper commitments from individual partners. Many aspects of the RTAs that they have negotiated

with developing countries since 1995 have been TRIPS-plus, GATS-plus, or otherwise WTO-plus in the general rules and

specific commitments that they achieve.

The second way in which the U.S. and E.U, approaches to RTAs are related to the WTO concerns the introduction of yet

more issues. Just as the United States had sought during the time of the Uruguay Round to introduce the new issues of

services, investment, and intellectual property rights to trade negotiations, so too have Washington and Brussels sought

during the time of the Doha Round to introduce even newer issues such as labor rights, environmental protection, and

deeper disciplines regarding government procurement, state-trading enterprises, and competition policy. These are all issues

that the United States and the European Union promoted for inclusion in the Doha agenda, but were largely unsuccessful in

convincing the mass of WTO members to go along with that plan. They have instead fallen back on RTAs as an opportunity

to win concessions on these issues. To a considerable extent, the commitments that the United States is now seeking on

these same issues in the TPP represent a regionalization of topics on which it has already been negotiating in a one-by-one

basis for the past two decades.

The question then becomes, will the bargains that are struck on these issues in the TPP then set precedents for adoption by

still more countries? There are three ways that this could happen. One is by the adherence of new countries to the TPP,

which might happen either in the final days of the original negotiation or, after that agreement is concluded and

implemented, by the accession of new countries to the agreement. Another possibility is that these same bargains will be

picked up, perhaps with further modifications, in agreements that the United States and other TPP countries reach with more

partners in other quarters of the globe. Yet a third possibility is that these precedents might be taken up in the WTO itself,

either as part of a final deal to resolve the Doha Round or (perhaps more realistically) in some new configuration of

negotiations.

This may be more easily said than done. It would be a mistake to think of RTAs only as smaller versions of the WTO, or to

assume that any topics on which they negotiate can be easily taken up in the WTO. To the contrary, there is little evidence

to suggest that the WTO membership as a whole is any more disposed towards negotiating on the newest issues now than it

was a decade ago. Moreover, when countries choose to negotiate via RTAs they may be foreclosing the possibility of

bargaining on some topics that can be dealt with only at the global level. Agricultural production subsidies the best example

of such an issue, which is a simple function of how these subsidies operate: Whereas it is quite simple to discriminate among

partners in the application of tariffs on imports, there is no practical way to restrict the impact of production subsidies to

some countries while exempting others.

Can the TPP and Other RTAs Provide a Substitute for the Multilateral System?

These last points return us to one of the more vexing problems that the global trading system now faces, which is how it

may reconcile the two tracks that most countries are now taking in their negotiations. The WTO runs uneasily alongside the

large and growing system of RTAs, and two developments exacerbate the challenges that RTAs pose to the multilateral

SELA Antenna in the United States

N 113 July 2015

trading system. One is the sheer number of these discriminatory agreements that have lately been negotiated. The great

irony of the WTOs establishment in 1995 is that it culminated a half-century of progress towards a comprehensive and

multilateral trade regime, but came just when its members began negotiating discriminatory agreements in earnest. The rate

at which RTAs entered into effect had been 2.1 per year during 1980-1994, most of them coming at the end of that period,

but rose to 9.0 per year in the early years of the new regime (1995-2003) and then to 13.9 over the past decade (20042014).2

The second challenge comes from the rise of the megaregional negotiations that encompass the worlds largest economies.

Whereas giants such as China, the European Union, Japan, and the United States had long shown restraint in their

negotiation of RTAs, reaching these agreements with smaller partners but dealing with one another solely in the multilateral

system, they have now broken through that glass ceiling in a series of transatlantic, trans-Pacific, and other negotiations. In

addition to the TPP, the other megaregionals include the TTIP between the European Union and the United States, as well as

negotiations that Japan is pursuing with the European Union and China (the latter in a trilateral initiative that also

encompasses Korea). Taken together, these negotiations signal a markedly new phase in the negotiation of discriminatory

agreements.

The smaller countries that make up the great majority of the WTO membership have little opportunity to influence these

major trends. With progress stalled at the multilateral level, the major decision that most of them face is whether they should

join in the rush to negotiate RTAs with the major economies. From these countries perspective, can the negotiation of a

series of agreements substitute for the effective functioning of a comprehensive and non-discriminatory multilateral trading

system?

There is no easy answer to that question. It is true on the one hand that some countries can achieve something close to

100% coverage of their trade in RTAs; Chile is the principal example of such a country in the Americas, and there are similar

examples elsewhere (e.g., Israel and Singapore). For reasons discussed above, however, these RTAs cannot be seen simply

as smaller versions of the WTO. The issues that they cover, and hence the commitments that are demanded of their

members, will be deeper on some issues than the WTO while also being shallower on others. Yet a third way in which RTAs

differ from a multilateral system is in the political implications that they may carry. While trade policymakers may hope to

treat theirs as an essentially apolitical field of public policy, it can be difficult to escape the impression that a message is

being sent when they negotiate agreements with some partners and not with others. In the current political environment, the

main decision that countries face in this respect is how they will deal with the growing rivalry between China and the United

States. No matter which choice a country makes among the four possibilities that is, an FTA with China but not the United

States, or vice versa, or with both, or with neither its decision may be seen as more than merely commercial in nature.

This is a point on which the publics in TPP countries hold rather different views, as may be appreciated from the opinion data

illustrated in Figure 2. With one exception, the data show a direct relationship between geographic distance and partner

preference. Whereas U.S. neighbors Mexico and Canada have a strong preference for ties to the United States rather than

China, the opposite may be observed in Pacific countries Australia and Malaysia. Chile and Peru each represent a middle

case, geographically as well as politically, where the publics have clear but not overwhelming preferences for the United

States over China. The one exception to this general rule is Vietnam, an immediate neighbor of China that has long had

difficult relations with that country.

As a practical matter, the most pressing question is whether we may see China joining the TPP. Were that to happen, the

agreement might by covering three of the worlds four largest economies amount to the next best thing to a multilateral

trade agreement. There are strong reasons to expect, however, that policymakers in the United States would object strongly

to such a development. This may be the one issue in trade policy for which Democrats and Republicans are in real

agreement, with members of both parties seeing China much more as an economic and political rival than as a commercial

partner. The experience with Japan suggests that concerns of this sort can be reversed over time, but that time does not

appear to be anywhere in the immediate future.

Those U.S. views may thus block China from becoming a TPP member, but that has not prevented other TPP countries from

negotiating with Beijing. In fact, Mexico and Canada are the only other TPP participants that neither have an FTA with China

nor are negotiating such an agreement. Most other TPP partners have already had an RTA in effect with China for several

years: Chile has since 2006, Peru since 2009, and New Zealand since 2008, while the members of the Association of

Southeast Asian Nations which includes TPP countries Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam have had an FTA with

China since 2005. Australia was the latest TPP participant to conclude FTA negotiations with China, having signed its

agreement on June 17. Japan is the only other country with which negotiations are still underway, with Tokyo having been

engaged in FTA negotiations with Beijing (together with Seoul) since late 2013.

2

Calculated from data on the WTOs Regional Trade Agreements Information System at http://rtais.wto.org/UI/PublicMaintainRTAHome.aspx.

SELA Antenna in the United States

N 113 July 2015

Figure 2: Public Perceptions of Ties with China and the United States in Selected Countries

Question: Is it more important for [the country] to have strong economic ties with China or with the United States?

Source: Pew poll at http://www.pewglobal.org/files/2015/06/Balance-of-Power-Report-TOPLINE-FOR-RELEASE-June-232015.pdf, Question 26a. Note that the poll did not include Brunei, Japan, New Zealand, or Singapore.

As can be seen from the data in Table 2, there are several SELA Member States that are negotiating multiple RTAs with the

largest economies. That trend is most notable in the case of the three that are also in the TPP, followed by the three others

that might be TPP candidates. Beyond those half-dozen countries, however, most others in the Americas have thus far

restricted.

Table 2: Trade Agreements between SELA Member States and Selected Large Economies

North Atlantic Economies

Current LAC/TPP

Chile

Mexico

Peru

Potential LAC/TPP

Colombia

Costa Rica

Panama

Other Central America

El Salvador

Guatemala

Honduras

Nicaragua

El Salvador

Other Caribbean

Bahamas

Barbados

Belize

Cuba

Dominican Republic

Canada

European

Union

United

States

Asian Economies

China

Japan

Korea

SELA Antenna in the United States

N 113 July 2015

9

North Atlantic Economies

Guyana

Haiti

Jamaica

Suriname

Trinidad & Tobago

Other South America

Argentina

Bolivia

Brazil

Ecuador

Paraguay

Uruguay

Venezuela

Canada

European

Union

United

States

Asian Economies

China

Japan

Korea

Key:

= RTA in effect

= RTA under negotiation

= RTA negotiations suspended

= RTA pending

Source: Tabulated from data in the WTOs Regional Trade Agreements Information System at

http://rtais.wto.org/UI/PublicMaintainRTAHome.aspx.

Their RTA negotiations with major extra-regional economies if they pursue any at all to their partners in the North

Atlantic. Central American countries have agreements with all three of these major economies, and most Caribbean countries

have concluded RTAs with Canada and the European Union. Seven other countries in South America have thus far refrained

from negotiating RTAs, apart from the sporadic efforts to reach such an agreement between the European Union and

Mercosur. In the event that the world is indeed headed towards a system in which the WTO is quiescent and the momentum

passes to megaregionals such as the TPP, these may be among the countries that are at greatest risk of being sidelined from

negotiations and damaged through trade diversion.

También podría gustarte

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2102)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- 1 Modigliani MillerDocumento3 páginas1 Modigliani MillerVincenzo CassoneAún no hay calificaciones

- GR 12 - Rbcpb-CoDocumento8 páginasGR 12 - Rbcpb-CoDan MarkAún no hay calificaciones

- Banglore Transport DirectoryDocumento28 páginasBanglore Transport DirectoryPritam Mahto0% (1)

- Invoice W1069034593 1539290420Documento2 páginasInvoice W1069034593 1539290420Kewal GuglaniAún no hay calificaciones

- Class-12-Accountancy-Part-2-Chapter-6 SolutionsDocumento41 páginasClass-12-Accountancy-Part-2-Chapter-6 Solutionssugapratha lingamAún no hay calificaciones

- Traporters ListDocumento3 páginasTraporters Listseema_suhag87Aún no hay calificaciones

- CH 1 Why Study Money, BankingDocumento15 páginasCH 1 Why Study Money, BankingLoving GamesAún no hay calificaciones

- Compound Interest1Documento6 páginasCompound Interest1Biomass conversionAún no hay calificaciones

- Payment Advice: Document Your Document Date Deductions Gross AmountDocumento12 páginasPayment Advice: Document Your Document Date Deductions Gross AmountArvind KotagiriAún no hay calificaciones

- Evolution of Taxation in The PhilippinesDocumento16 páginasEvolution of Taxation in The Philippineshadji montanoAún no hay calificaciones

- Cash Budgeting Examples.Documento21 páginasCash Budgeting Examples.Muhammad azeem83% (6)

- FX AC 13 Transfer and Business Taxes - INTRUZO ANSWERDocumento6 páginasFX AC 13 Transfer and Business Taxes - INTRUZO ANSWERPam IntruzoAún no hay calificaciones

- e-StatementBRImo 187601004955500 Oct2023 20231027 151203Documento3 páginase-StatementBRImo 187601004955500 Oct2023 20231027 151203Victor Eman AbuthanAún no hay calificaciones

- CFAS Reviewer - Module 6Documento14 páginasCFAS Reviewer - Module 6Lizette Janiya SumantingAún no hay calificaciones

- 318 Mcqs and AnswersDocumento14 páginas318 Mcqs and Answersmuyi kunleAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 6 - Financial AccountingDocumento10 páginasChapter 6 - Financial AccountingLinh BùiAún no hay calificaciones

- Concept of MoneyDocumento12 páginasConcept of MoneyHamidi HamidAún no hay calificaciones

- Financial Services Notes - Jeganraj - 2020Documento23 páginasFinancial Services Notes - Jeganraj - 2020jeganrajraj100% (1)

- Statement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDocumento6 páginasStatement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceArnav SudhindraAún no hay calificaciones

- Basic Crypto Currency TradingDocumento34 páginasBasic Crypto Currency TradingAAún no hay calificaciones

- Tax Invoice: Account No. 5742504365Documento1 páginaTax Invoice: Account No. 5742504365vishnuvarthanAún no hay calificaciones

- CH 3 National Income and Related AggregatesDocumento2 páginasCH 3 National Income and Related AggregatesSoumya DashAún no hay calificaciones

- Solve The Following Crossword Round Your Final Answers To TheDocumento3 páginasSolve The Following Crossword Round Your Final Answers To TheAmit PandeyAún no hay calificaciones

- CIR v. SeagateDocumento12 páginasCIR v. SeagatePaul Joshua SubaAún no hay calificaciones

- Sold-To Party Address Information: Sales Order DetailsDocumento1 páginaSold-To Party Address Information: Sales Order Detailsshakilmagura9424Aún no hay calificaciones

- Full Download Cornerstones of Financial Accounting Canadian 1st Edition Rich Solutions ManualDocumento36 páginasFull Download Cornerstones of Financial Accounting Canadian 1st Edition Rich Solutions Manualcolagiovannibeckah100% (30)

- 2023 (ASSIGNMENT) Mathematics in Practical SituationsDocumento16 páginas2023 (ASSIGNMENT) Mathematics in Practical Situationsalibabagoat1Aún no hay calificaciones

- Binder 1Documento107 páginasBinder 1Ana Maria Gálvez Velasquez0% (1)

- Activity1.1 Historical Tracing Activity (Format Sample)Documento3 páginasActivity1.1 Historical Tracing Activity (Format Sample)Christian Jay Vega CorpuzAún no hay calificaciones

- Shipping TerminologyDocumento18 páginasShipping Terminologyamtris406Aún no hay calificaciones