Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Transformation of The Institutional Structure of Western Balkan Countries

Cargado por

srdjaTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Transformation of The Institutional Structure of Western Balkan Countries

Cargado por

srdjaCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

3rd International Symposium on Sustainable Development, May 31 - June 01 2012, Sarajevo

Velasquez, M.G. (2006). Business Ethics Concepts & Cases. 6. Ed. Upper Saddle River:

Pearson.

Transformation Of The Institutional Structure Of Western Balkan Countries

ermin enturan1, Samir Husi2

1Blent Ecevit University, Zonguldak/Turkey

2International University of Sarajevo,Bosnia and Herzegovina

E- mails: senturansermin@gmail.com, samirhusic@gmail.com

Abstract

Transformation of the institutional structure affects economic development both from the

cost of transactions aspect and the operating costs. In development theory it is usual to define

development as economic growth plus structural change. But in the framework of

institutional economic theory development could be defined as economic growth plus

appropriate institutional change, meaning institutional changes which facilitate further

economic growth.There are several factors influencing reforms in the Western Balkan

countries. Those countries prove that institutions can successfully change at the time of crisis.

Although the general rule shows strong correlations among the many reform measures, some

institutions develop independently of other measures of institutional or organizational reform.

As it is emphasized on the role of institutions in growth and development, it should be also

recognized that institutions can change regardless of undesirable environmental factors.

Keywords : institutional change, economic transition, Western Balkan Countries

1.INTRODUCTION

Transformation of the institutions in a new market economies have been mostly radical in an

astonished and unpredictable direction. Numerous factor influenced reforms that followed in

liberalization of prices, privatization, opening of economy to the foreign investments,

liberalization of the foreign exchange market, and the reduction of foreign trade restrictions.

The main dimensions along which various national capitalist systems can be placed are the

corporate governance and macroeconomic institutional environment (Cernat, 2001).

Corporate governance and business-state relations influenced choice and path that economies

in transition undertaken. Regardless of strong efforts, disintegration of these economies

suffered severe contraction due to collapse of export demand from former trading partners,

while domestic demand declined.

234

3rd International Symposium on Sustainable Development, May 31 - June 01 2012, Sarajevo

Post-Communist Transition was mainly confronted with institutional transformation.

Different concepts of institutions created different paths of transformations. At the beginning

of the 1990`s, Central and Eastern European Countries (CEE) and Former Soviet Union

Republics started with transformation towards market economy. Both the economic and the

institutional frameworks were significantly changed. Today in the CEEs there are

developing guarantees of private property, new banks, new economic and administrative

organizations, and other formal institutions imposed in a transitional time and by political

resolution.

Transformation of the institutional structure affects economic development both from the cost

of transactions aspect and the operating costs. It will be argued further on that key challenge

for governance in Western Balkan post-conflict period was institutional transformation

required for successful and sustainable economic growth.

Transition is a very complex process, since in the market economy the capital and labor

allocation is completely different than in the centrally planned economy. All the formal

institutions such as stock exchange, banks, investment funds, trade unions, property rights,

enterprise confederations, and others are new. Their development is slow and affected by a

learning process. Because of that, a shock therapy was a poor strategy and likely brought

important recession in Western Balkans in the early 90's (Tridico, 2005). Anglo-Saxon

variant of capitalism, or so called Atlantic capitalism (Hodges and Woolcock, 1993) has

certain specific fundamental institutional characteristics. Those characteristics involve the

role of the state to maintain a stable environment for markets to operate freely from any

political or social interference.

2.Objectives of the economic institutional structure reforms

There is general agreement that systematic transformation of the institutions implies

fundamental reforms in most of the areas. Such areas and institutional reforms are recognized

in many political party programs of transitional countries, like in Bosnia and Herzegovina

(Avdic and Meedovic, 2006). Many of above mentioned structural transformations already

started in Western Balkan countries but had not been successfully implemented to the end.

Reasons for those failures are complex, and most common one is missing political

willingness to implement reforms.

Usually decision makers are promoting reforms, especially in pre-election periods, but in

reality they try to preserve situation unchanged and to continue to rule in the same manner.

Sometimes decision makers did not achieved previously necessary institutional changes, so

reforms are prevented to go faster. Very common in transition countries is lack of knowledge

and expertise among policy decision-makers, which could not be overcome except with

foreign support (Filipovic, 2006).

3.The negative effects of institutional transition

235

3rd International Symposium on Sustainable Development, May 31 - June 01 2012, Sarajevo

In the first years of transition, the most important aim of Government was macrostabilization: the fight against inflation, the reduction of debt, the liberalization of prices, the

budget balance and privatization. All these aims were considered necessary by international

organizations and main stream economists to allow economic growth. Nevertheless these

results were not sufficient to stimulate long-term and sustainable growth. Transition

economies are affected by very high unemployment rates, a growing inequality rate, a

considerable index of poverty, a chronic current account deficit and a considerable foreign

debt. Moreover informal economy and corruption levels strongly persist.

Economic transition countries of the former Yugoslavia, experienced tragic events, civil

wars, crime domination and economy of chaos. Therefore they did not implement any

institutional policies which would allow for an institutional governance, for the protection of

weaker and poorer people, or for conflict management. On the contrary, the sudden

introduction of the market economy and the end of social policies, welfare state and income

redistribution policies caused an increase in poverty, inequality and unemployment (Adam,

1999).

In order to expand human capabilities institutions are needed. Institutional policies would

allow for improving the three essential capabilities for human development: leading long and

healthy lives, being knowledgeable and having a decent standard of living. This approach

assumes that economic growth requires first of all investment in human development.

Countries which implemented institutional policies, social policies and a governance

recovery, increased their level of human development. On the contrary, countries which did

not implement such institutional policies did not increase their level of human development,

and their economic growth was neither fast nor sufficient to recover the pre-1989 level of

GDP per capita (Tridico, 2005).

4.Present position of Western Balkan countries

Western Balkan countries proven after twenty years that only radical transformation of the

institutional structure can lead them to the successful EU economy. Certain attempt to make

small or incremental changes to the old institutional solutions, sooner or later become

ineffective and just time consuming. Such small changes to the institutional arrangements

happened quite frequently, though, so they produced a variety of organizational solutions

based on old institutional framework.

Considering advancement in development of the institutional structures, today we can

classify all transition economies into three main categories (Filipovic, 2006):

(a) The most successful economies in transition that provides stable economic growth rates,

establish institutional framework comparable with developed economies and that already

deeply enter into European integration (or become a full member states of the EU);

(b) Relatively successful economies in transition that has temporary episodes of successes

measured by economic and social performances - first of all through low level of inflation,

high rate of GDP growth and avoiding of mass unemployment, but also followed by short

236

3rd International Symposium on Sustainable Development, May 31 - June 01 2012, Sarajevo

episodes of destabilization and worsening of their performances. Typical representatives in

this group are some of Western Balkans countries, like Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro, etc.;

(c) Third group of countries in transition are the most obsolete countries, with slow and not in

depth institutional changes, countries that are still at the beginning of the transition process

and that miss enough courage to cope with the changes transition must comprised. In this

group are most of the former Soviet Union members.

The most successful transition economies, mentioned above, already becomes a full member

of EU, accepting European standards, organizational structures and most important European

institutional framework. Those countries liberalized their markets and open it to foreign

direct investment inflow in early 1990s, so most attractive investments and profitable

opportunities for old EU investors are already reduced. On the other hand, in Western Balkan

countries there are still some obstacles for their faster integration in European institutional

framework: most of them lack transparent and effective judicial system, there is still

inefficient implementation of laws, every new election are considered as potential change and

turbulence in economic system.

5.Institutional structure reforms in Western Balkan countries

The socialist economy was characterized by strong state intervention in economy which

manifested itself through all-encompassing price control, subvention of enterprises, etc.

Elimination of subventions and liberalization of market and prices at the beginning of 90s,

together with an inadequate production structure, caused accumulation of losses in state

companies. In spite of their losses, yet, the companies continued to operate. Their

preservation was motivated by the avoidance of huge social costs which might arise in the

case of their closure (Golubovic, 2005).

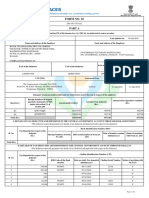

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) summed up, using

transitional indicators, the advancement of structural and institutional reforms in the year

2010 for 29 countries in transition. Eleven transitional indicators encompass six main

transitional areas: liberalization, privatization, companies, infrastructure, financial

institutions, and the legal environment. Each indicator shows a synthesized assessment of

improvement achieved in a certain area, based on various data, narrative information and

analyses (EBRD, 2010).

Countries in transition continued to advance in their structural and institutional reforms with

various levels of success in last decade. Countries of South-East Europe advanced

significantly, Baltic states and Central and East European countries achieved some

advancement, while the advancement in newly independent states was modest. Comparison

of the average yearly transitional index between economies in transition shows that in 2004

21 countries (scope 2,6-3,9) were more advanced than Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and

Herzegovina, while only Turkmenistan, Belarus, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan showed results

that were lower (EBRD, 2004).

237

3rd International Symposium on Sustainable Development, May 31 - June 01 2012, Sarajevo

Albania

Bosnia and

Herzegovina

Croatia

FYR

Macedonia

Montenegro

Serbia

Population mid2010 (million)

3,2

3,8

4,4

2,0

0,7

9,9

Private sector share

of GDP mid-2010

(EBRD estimate in

per cent)

75

60

70

70

65

60

Large-scale

privatisation

4-

3+

3+

3+

3-

Small-scale

privatisation

4+

4-

4-

Governance and

enterprise

restructuring

2+

3-

2+

Price liberalisation

4+

4+

Trade and foreign

exchange system

4+

4+

4+

Competition policy

2+

2+

Banking reform and

interest rate

liberalisation

Securities markets

and non-bank

financial

institutions

2-

2-

3-

2-

Overall

infrastructure

reform

2+

3-

3-

2+

2+

Table 1: Transition indicator scores 2010. - Enterprises Markets and trade Financial institutions

Infrastructure. Source: EBRD, 2010.

According to the EBRD assessment, in 2010 Albania has made steady progress with

structural reform, despite having to overcome serious institutional weaknesses and one of the

most difficult starting points for transition. In 2009, Albania submitted a formal application

for EU membership. However, the country faces major reform challenges in a number of

areas. The need to improve the quality of the infrastructure is a requirement, although the

238

3rd International Symposium on Sustainable Development, May 31 - June 01 2012, Sarajevo

government does have major investment plans for roads, railways and electric power. The

banking sector has limited reach as a source of finance outside of the main cities, and nonbank financial institutions are at a very early stage of development.

Bosnia and Herzegovinas progress in transition has been effectively stalled for some years,

and as a result the country lags behind all others in south-eastern Europe. The countrys

complicated political and constitutional structure is a major hindrance to reform and good

governance. A significant privatisation agenda lies ahead but, in the FBH at least, there

appears to be little appetite for bringing major enterprises slated for sale to the market. As a

result of the reform paralysis, the country also lags behind other EU candidates or potential

candidates in the region in terms of EU approximation.

Croatia has long been considered among the most advanced of the transition countries, with a

broadly liberalised economy, a relatively high degree of sophistication in financial services,

and a country where significant progress has been made on infrastructure reform. The

banking sector weathered the financial crisis well and remains sound and liquid. However,

some major enterprises and financial institutions continue to rely on state subsidies although

the level of subsidies has fallen significantly since 2005. The quality of the business

environment remains a concern, according to cross-country surveys, and reflects the need to

tackle obstacles to doing business, such as the cumbersome permit process, as well as the

need to implement urgent public administration reforms.

Progress in reform in FYR Macedonia throughout the transition period has been steady if

somewhat slow, as the country has been hampered by weak administrative and institutional

capacity. In the financial sector competition among banks is less vibrant than in neighboring

countries and the development of capital markets is in its infancy. The countrys

infrastructure also faces significant investment needs in the coming years.

The Montenegrin authorities have made important advances in several areas, notably in price

and trade liberalisation and financial sector development. Privatization is advanced, with

most state assets having been sold off. The banking sector had grown very rapidly in the

years before the crisis and progress has been made in strengthening supervisory and

regulatory structures. Lastly, Montenegro has had some success in creating a favorable

business climate and in attracting reputable foreign investors. Nevertheless, the country still

has a significant transition agenda ahead. The challenges are particularly large in the

infrastructure sector, notably in the power sector, which is crucial to supporting economic

activity.

Serbia began the transition later than most other countries, but has been catching up steadily

over the past decade. Nevertheless, a major structural reform agenda still lies ahead. The

challenges are particularly large in most infrastructure sectors, especially in the energy sector,

which remains dominated by one state-owned company. A significant number of large

enterprises also await privatisation once market conditions improve, both in the corporate

sector and in parts of the financial sector, including the largest insurance company (EBRD,

2010).

239

3rd International Symposium on Sustainable Development, May 31 - June 01 2012, Sarajevo

6.CONCLUSIONS

Effective institutional restructuring is not a question of adaptation of foreign rules and

standards, but more the question of gradual and persistent time consuming process. Societies

have different own norms and tradition, and their institutional building of formal rules are

based on informal one. Transformation of these formal rules are often radical, especially

when organizations with different interest emerge, and when institutional change cannot be

mediated through the existing institutional framework.

During transitional period, a great deal of effort of the international financial institutions was

devoted to support of institutional building, as it was recognized as priority in transition

economies. The reform index is both proven as a measure of the extent of reform, and a

measure of institutional change. Economic growth is powerfully associated with that index.

Western Balkan countries prove that institutions can successfully change at the time of crisis.

Although the general rule shows strong correlations among the many reform measures, some

institutions develop independently of other measures of institutional or organizational reform.

As we emphasize the role of institutions in growth and development, we should also

recognize that institutions can change regardless of undesirable environmental factors.

The change of the financial sector reform in the Balkan countries in transition was different

from the transition economies of Central Europe, since no radical changes took place in this

sector in the Balkans. The Balkan countries accepted a gradualist approach to the financial

sector reform stressing some other aspects of transformation. These countries' experiences in

the nineties points out that partial institutional changes do not create a favorable environment

for structural changes. Rather, structural reforms require integral and harmonized changes in

all its segments. Both formal and informal structural change can contribute to growth, and the

more structural transformations are made, the more rapidly the economy grow.

REFERENCES

Adam, J. (1999). Social costs of Transformation to a Market Economy in Post-Socialist

Countries, the case of Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary. MacMillan Press, New

York.

Avdic, A. & Meedovic, A. (2006). Analiza ekonomskih platformi politikih stranaka u BiH.

Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, Sarajevo.

Cernat, L. (2001). Institutions and Economic Growth: What Model of Capitalism for Central

and Eastern Europe? Conference on Institutions in Transition, Slovenia, July 2001.

EBRD (2004). European Bank for Reconstruction and Development - Transition Report

2004: Infrastructure. http://www.ebrd.com/downloads/research/transition/TR04.pdf

EBRD (2010). European Bank for Reconstruction and Development - Transition Report

2010: Recovery and Reform. http://www.ebrd.com/downloads/research/transition/tr10.pdf

240

3rd International Symposium on Sustainable Development, May 31 - June 01 2012, Sarajevo

Filipovic, M. (2006). Importance of Institutional Development for Western Balkan Countries.

46th European congress of the Regional Science Association Enlargement, Southern Europe

& Mediterranean. Volos, Aug. 30- Sep. 3 2006. Belgrade, April, 2006.

Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States. (2011, June). Federal Reserve Statistical

Release. Retrieved from http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/current/data.htm

Golubovi, S., & Golubovi, N. (2005). Financial Sector Reform in the Balkan Countries in

Transition. Economics and Organization Vol. 2, No 3, 2005, University of Ni, pp. 229

236.

Hodges, M., Woolcock, S. (1993). Atlantic Capitalism versus Rhine Capitalism in the

European Community. Frank Cass & & co ltd, Great Britain.

Tridico, P. (2005). Institutional Change and Human Development in Transition Economies.

European Association for Evolutionary Political Economy. EAEPE Conference paper,

November 2005, Bremen (Germany).

Empowerment At Higher Educational Organizations

Aermin enturan1, Julijana Angelovska2

1Blent Ecevit niversity, Zonguldak/Turkey

2International Balkan University, Skopje/Makedonia

E- mails : senturansermin@gmail.com, julijana.angelovska@yahoo.com

Abstract

Empowerment is a concept which is widely used in management and many managers and

professional in various organizations claim to be practicing it. The objective of this study was

to assess the construct validity and internal consistency of the Psychological Empowerment

Questionnaire (PEQ) for employees in higher education. The PEQ was administered at

private university in Skopje. The study is empirical research on psychological empowerment,

and more specifically research regarding a tool that can be used to assess the level of

psychological empowerment of employees in higher education organisations. If

psychological empowerment can be measured in a reliable and valid manner, interventions

can be implemented to promote the empowerment of employees.

Exploratory factor analysis is used to verify the validity of the psychological empowerment

comprising four cognitive dimensions i.e. meaning, competence, self-determination and

impact in the context of private higher education institutions The subscales showed

acceptable internal consistencies. Psychological empowerment can be measured in a reliable

and valid manner in higher educational organizations.

241

También podría gustarte

- Lap2003 02Documento19 páginasLap2003 02srdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Dictionary of Sports Terminology: InformationDocumento2 páginasDictionary of Sports Terminology: InformationsrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Physical and Physiological Characteristics of Elite Serbian Soccer PlayersDocumento7 páginasPhysical and Physiological Characteristics of Elite Serbian Soccer PlayersMustafa AadelAún no hay calificaciones

- Some Mental Faculties of The Top SportsmenDocumento8 páginasSome Mental Faculties of The Top SportsmensrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Pas2001 10Documento5 páginasPas2001 10srdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Lap2000 10Documento16 páginasLap2000 10srdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Pas99s 05Documento9 páginasPas99s 05srdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Development Policy as an Ill-Structured ProblemDocumento8 páginasDevelopment Policy as an Ill-Structured ProblemsrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Social and Ethnic Distance Towards Romanies in Serbia: Facta UniversitatisDocumento15 páginasSocial and Ethnic Distance Towards Romanies in Serbia: Facta UniversitatissrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Dasein and The Philosopher: Responsibility in Heidegger and MamardashviliDocumento21 páginasDasein and The Philosopher: Responsibility in Heidegger and MamardashvilisrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Mining Equipment SelectionDocumento8 páginasMining Equipment Selectiondfim477Aún no hay calificaciones

- Identity as a Problem of Today: Loss of Identity and Subjectivity in Modern GlobalizationDocumento8 páginasIdentity as a Problem of Today: Loss of Identity and Subjectivity in Modern GlobalizationsrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Lap2003 02Documento19 páginasLap2003 02srdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Costs Management For A Profitable New Product Development: Facta UniversitatisDocumento8 páginasCosts Management For A Profitable New Product Development: Facta UniversitatissrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Motor skills impact on boys and girls fundamentalsDocumento9 páginasMotor skills impact on boys and girls fundamentalssrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Pe200701 10nDocumento14 páginasPe200701 10nsrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Pas2011 01Documento11 páginasPas2011 01srdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Motor Learning in SportDocumento15 páginasMotor Learning in SportsdjuknicAún no hay calificaciones

- Pas2000 06Documento6 páginasPas2000 06srdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Roots of Physical Culture ProfessionDocumento7 páginasRoots of Physical Culture ProfessionsrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Development Policy as an Ill-Structured ProblemDocumento8 páginasDevelopment Policy as an Ill-Structured ProblemsrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Pe2003 04Documento9 páginasPe2003 04srdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Lap2006 02Documento8 páginasLap2006 02srdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Local Charges and Prices For Municipal Services in Bulgaria: Facta UniversitatisDocumento8 páginasLocal Charges and Prices For Municipal Services in Bulgaria: Facta UniversitatissrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Constitutional Competence for International TreatiesDocumento15 páginasConstitutional Competence for International TreatiessrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Terminological Dilemmas of The Profession: Abstract. Language Is Not Only The Oldest Cultural Monument of Mankind and ItsDocumento7 páginasTerminological Dilemmas of The Profession: Abstract. Language Is Not Only The Oldest Cultural Monument of Mankind and ItssrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Origin and Development of Political Parties in Serbia and Their Influence On Political Life IN THE PERIOD 1804-1918Documento10 páginasOrigin and Development of Political Parties in Serbia and Their Influence On Political Life IN THE PERIOD 1804-1918srdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Lap98 05Documento24 páginasLap98 05srdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- The Relational Aspect of The Business Environment: Facta UniversitatisDocumento8 páginasThe Relational Aspect of The Business Environment: Facta UniversitatissrdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Eao97 05Documento9 páginasEao97 05srdjaAún no hay calificaciones

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (265)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2099)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- OpTransactionHistoryTpr09 04 2019 PDFDocumento9 páginasOpTransactionHistoryTpr09 04 2019 PDFSAMEER AHMADAún no hay calificaciones

- Form 16 TDS CertificateDocumento2 páginasForm 16 TDS CertificateMANJUNATH GOWDAAún no hay calificaciones

- Economics 2nd Edition Hubbard Test BankDocumento25 páginasEconomics 2nd Edition Hubbard Test BankPeterHolmesfdns100% (48)

- Rab 7x4 Sawaludin Rev OkDocumento20 páginasRab 7x4 Sawaludin Rev Ok-Anak Desa-Aún no hay calificaciones

- 2013 Factbook: Company AccountingDocumento270 páginas2013 Factbook: Company AccountingeffahpaulAún no hay calificaciones

- Weimar Republic Model AnswersDocumento5 páginasWeimar Republic Model AnswersFathima KaneezAún no hay calificaciones

- Pengiriman Paket Menggunakan Grab Expres 354574f4 PDFDocumento24 páginasPengiriman Paket Menggunakan Grab Expres 354574f4 PDFAku Belum mandiAún no hay calificaciones

- Monitoring Local Plans of SK Form PNR SiteDocumento2 páginasMonitoring Local Plans of SK Form PNR SiteLYDO San CarlosAún no hay calificaciones

- Espresso Cash Flow Statement SolutionDocumento2 páginasEspresso Cash Flow Statement SolutionraviAún no hay calificaciones

- Minnesota Property Tax Refund: Forms and InstructionsDocumento28 páginasMinnesota Property Tax Refund: Forms and InstructionsJeffery MeyerAún no hay calificaciones

- PDF1902 PDFDocumento190 páginasPDF1902 PDFAnup BhutadaAún no hay calificaciones

- NSE ProjectDocumento24 páginasNSE ProjectRonnie KapoorAún no hay calificaciones

- RajasthanDocumento5 páginasRajasthanrahul srivastavaAún no hay calificaciones

- Samurai Craft: Journey Into The Art of KatanaDocumento30 páginasSamurai Craft: Journey Into The Art of Katanagabriel martinezAún no hay calificaciones

- Industrial Visit ReportDocumento6 páginasIndustrial Visit ReportgaureshraoAún no hay calificaciones

- Ielts Writing Task 1-Type 2-ComparisonsDocumento10 páginasIelts Writing Task 1-Type 2-ComparisonsDung Nguyễn ThanhAún no hay calificaciones

- Tax Invoice: Tommy Hilfiger Slim Men Blue JeansDocumento1 páginaTax Invoice: Tommy Hilfiger Slim Men Blue JeansSusil Kumar MisraAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 7 Variable CostingDocumento47 páginasChapter 7 Variable CostingEden Faith AggalaoAún no hay calificaciones

- Reimbursement Receipt FormDocumento2 páginasReimbursement Receipt Formsplef lguAún no hay calificaciones

- Bid Data SheetDocumento3 páginasBid Data SheetEdwin Cob GuriAún no hay calificaciones

- Eco Bank Power Industry AfricaDocumento11 páginasEco Bank Power Industry AfricaOribuyaku DamiAún no hay calificaciones

- Edwin Vieira, Jr. - What Is A Dollar - An Historical Analysis of The Fundamental Question in Monetary Policy PDFDocumento33 páginasEdwin Vieira, Jr. - What Is A Dollar - An Historical Analysis of The Fundamental Question in Monetary Policy PDFgkeraunenAún no hay calificaciones

- Rent Agreement - (Name of The Landlord) S/o - (Father's Name of TheDocumento2 páginasRent Agreement - (Name of The Landlord) S/o - (Father's Name of TheAshish kumarAún no hay calificaciones

- Chapter 16 Planning The Firm's Financing Mix2Documento88 páginasChapter 16 Planning The Firm's Financing Mix2api-19482678Aún no hay calificaciones

- Act 51 Public Acts 1951Documento61 páginasAct 51 Public Acts 1951Clickon DetroitAún no hay calificaciones

- Report on Textiles & Jute Industry for 11th Five Year PlanDocumento409 páginasReport on Textiles & Jute Industry for 11th Five Year PlanAbhishek Kumar Singh100% (1)

- FWN Magazine 2017 - Hon. Cynthia BarkerDocumento44 páginasFWN Magazine 2017 - Hon. Cynthia BarkerFilipina Women's NetworkAún no hay calificaciones

- Globalization's Importance for EconomyDocumento3 páginasGlobalization's Importance for EconomyOLIVER JACS SAENZ SERPAAún no hay calificaciones

- "Tsogttetsii Soum Solid Waste Management Plan" Environ LLCDocumento49 páginas"Tsogttetsii Soum Solid Waste Management Plan" Environ LLCbatmunkh.eAún no hay calificaciones

- Society in Pre-British India.Documento18 páginasSociety in Pre-British India.PřiýÂňshüAún no hay calificaciones