Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Update On BCS

Cargado por

doccommieTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Update On BCS

Cargado por

doccommieCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

An update on management of Budd-Chiari syndrome.

, 2014; 13 (3): 323-326

CONCISE

REVIEW

323

May-June, Vol. 13 No. 3, 2014: 323-326

An update on management of Budd-Chiari syndrome

Andrea Mancuso

Medicina Interna 1, ARNAS Civico-Di Cristina-Benfratelli, Palermo, Italy.

Epatologia e Gastroenterologia, Ospedale Niguarda C Granda, Milano, Italy.

ABSTRACT

The topic of this paper is to report an update on management of Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS). Actually, the

flow-chart of BCS management comes from experts opinion and is not evidence-based due to the rarity

of BCS. Management of BCS follows a step-wise strategy. Anticoagulation and medical therapy should be

the first line treatment. Revascularization or TIPS in case of no response to medical therapy. OLT as a

rescue therapy. Surgery has limited but important space, especially in cases with high inferior vena cava

obstruction not suitable for endovascular treatment. However, no clear indication can actually be given

about the timing of different treatments. Moreover, there is some concern about treatment of some

subgroup of patients, especially regarding the risk of recurrence after liver transplantation. This paper

propose a new algorithm of BCS management suggesting an earlier therapeutic approach when clinical

signs are evident.

Key words. Ascites. TIPS. Liver transplantation. Surgery. Outcome.

The aim of this paper is to propose a new algorithm of BCS management. In fact, as it will be discussed, evidence is lacking about BCS due to the

rarity of the syndrome. We will see that some data

argue against the actual expectant strategy of BCS

management and suggest a more interventional

approach.

The topic of this paper is to report an update on

management of Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS). BCS

is a rare disease with a generally worsening outcome without intervention. Following experts opinion

coming from not evidence-based experiences, BCS

management should follow a step-wise management.

In fact, medical therapy (anticoagulation, treatment

of underlying disease, symptomatic therapy of portal

hypertension complications) should be the first-line

treatment, angioplasty/stenting the second-line (in

patients with short-length stenoses not responding

to medical therapy), TIPS the next step (in patients

not responding to medical therapy and in case of no

response to, or stenoses unsuitable for, angioplasty/

Correspondence and reprint request: Andrea Mancuso, M.D.

Medicina Interna 1, ARNAS Civico, Piazzale Liotti 4, 90100, Palermo, Italy.

Tel.: 00393298997893, Fax: 00390916090252

E-mail: mancandrea@libero.it

Manuscript received: February 16,2014.

Manuscript accepted: February 25, 2014.

stenting) and liver transplantation (LT) the last

chance when TIPS is not effective. 1-3 Step-wise

management suggests moving forward when no

response to therapy appears.1

A therapeutic approach limited to short-length

stenoses is angioplasty/stenting, with a good medium

term outcome reported in some experience.4-6 However, no data can argue against the use of TIPS also in

the subgroup with short-length stenoses. In fact a

prospective comparison between TIPS and angioplasty/stenting has not been performed. Probably,

such a therapeutic choice in this subgroup of patients

should be personalized and based on local expertise.

The most frequent treatment for BCS is surely

TIPS.1-3 TIPS has been shown to be effective as BCS

treatment in early experiences. 7-9 Moreover, TIPS

can be successful also in the technically difficult

case of extension of thrombosis to the portal vein

tree.10,11 Finally, a multi-center experience provided

long-term data on TIPS treatment for 147 BCS

patients not responding to medical treatment or

recanalization. TIPS was successful in 124 BCS

patients, who were followed for a median of 36.7

months. Overall, 16 (13%) died, 8 (6.5%) underwent

OLT. Main complications were hepatic encephalopathy

in 21% and TIPS dysfunction in 41%. The 10-year

survival was 69%.12

Apart from LT, surgical treatment is generally

not contemplated in the BCS management by recent

324

Mancuso A.

guidelines.1 In fact, the most used treatment for

BCS non responsive to medical therapy is TIPS, LT

is used as a rescue therapy, while surgical treatments are limited to a strict minority of patients.1-3

Surgical shunts for BCS can be very successful, but

have been associated with rapid decompensation and

in-hospital mortality can be high (about 25%), primarily due to the patients poor general condition.13-16

In the past years, a surgical approach has been traditionally considered the first choice. In some series,

an excellent outcome with long-term follow-up has

been reported (95% survival, 3 to 28-year followup).15 However, in this series, the SSPCS was used,

an approach that cannot be used in case of inferior

vena cava (IVC) thrombosis or significant compression. In the same series, the mortality rates of patients with IVC involvement were very high after

traditional surgery (mesoatrial shunts) and better

results were described with another technique

(SSPCS + cavoatrial shunt) in 18 patients, all surviving after a follow-up of 5-25 years.15 However,

outcome after surgical portosystemic shunt is variable

and worse results were reported by others.13,14,16

In most of the above series, patients with liver failure were not considered for surgery but for liver

transplantation.13-16

Patients with BCS due to a IVC obstruction near

to the atrium constitute a difficult to treat subgroup

of BCS patients, whose management can benefit

from endovascular dilatation/stenting or surgical

treatment. Because of obvious reasons, TIPS does

not by-pass IVC obstruction, resulting ineffective.

Although some study describes the possibility of endovascular management for patients with IVC obstruction near to the atrium as safe and with good

long-term patency, data are scanty and need confirmation on a larger scale.17

The widest experience with a surgical shunt

approach for BCS due to a IVC obstruction was

the above reported after a combination of SSPCS

and cavo-atrial shunt: 18 patients, all surviving

after a follow-up of 5-25 years.15 Other surgical

techniques reported in that and other series either had unacceptable or non reported outcomes.13,14,16

We recently described a patient with IVC obstruction near to the atrium and a previous severe complication of a trial of endovascular management,

who had an excellent outcome after the replacement

of the obstructed segment of the IVC with a caval

homograft.18

LT is the last chance for BCS syndrome non responsive to either medical therapy or recanalization/

, 2014; 13 (3): 323-326

decompression.19-24 A European multi-center study

reported long-term data on 248 patients who underwent LT for BCS between 1988 and 1999. MPD was

the underlying syndrome in 45%. LT was performed

electively in 55%, in emergency in 21%. Hepatocellular carcinoma was incidentally found in explanted

liver in 3. Before LT, 19% had portal vein thrombosis and 16% IVC thrombosis. Median follow-up was

48 months. Overall, 67 (27%) died (49% in the first

month). Causes of death were sepsis in 47%, graft

dysfunction or hepatic artery thrombosis in 19%, venous thrombosis in 12%, cardiac in 9% and brain

damage in 5%. There was a significantly increased

mortality if LT was shortly after SPSS or TIPS.

Thirty-seven patients underwent re-LT (4 twice).

The 10-year survival was 68%. After 1 year there

were 9 deaths, seven of which were in MPD patients. Causes were: 4 BCS recurrence, 1 leukaemia

(7 years post-LT), 1 ovarian cancer, 1 colangitis, 2

not known. Anticoagulation after LT was performed

by 200/235 (18 heparin or aspirin), suspended in 10,

all of which were believed to have a cause of BCS reversible after LT (antithrombin III and Protein C

deficiency); all had an uneventful outcome but one

who reported pulmonary embolization 1 year after,

when anti-phospholipid syndrome was discovered.

Complications post-OLT in the patients treated with

anticoagulation were thrombosis in 27 (11%), 11 of

whom (41%) died; recurrence of BCS in 6 (1 ReOLT, 1 TIPS, 4 death); bleeding in 27 (11%), 2 of

whom died (intracranial bleeding). Prognostic Factors were pre-OLT renal function and pre-OLT

SPSS/TIPS.23 However, the prognostic factor of a

previous shunt before LT has to be weighed cautiously because it can only reflect the fact that patients who underwent TIPS before LT had the most

severe liver disease. Moreover, a recent American

multi-center study found no negative effect of TIPS

on the following LT outcome.24 Finally, recent data

show promising results of living donor LT for

BCS.25

The possibility of BCS underlying disease progression is a concern, in particular the development

of leukaemia in MPD after LT. Preliminary multicenter studies failed to draw conclusions on this topic, given that long-term outcome was not correlated

to t h e t y p e o f u n d e r l y i n g d i s e a s e p r e d i s p o s ing to BCS.23,24 However, although not statistically

significant, 7 of the 9 patients who died after 1 year

post LT in the European study had MPD.23 The impact of Jak2 and MPL mutations on prognosis of

splanchnic vein thrombosis (either BCS or portal

vein thrombosis) was recently reported in 241 cases.

An update on management of Budd-Chiari syndrome.

, 2014; 13 (3): 323-326

325

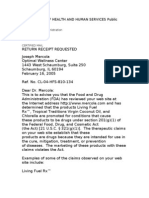

BCS diagnosis

Anticoagulation

Treatment of underlying disease

Ascites, esophageal/gastric varices and/or liver failure?

Yes

TIPS

Follow-up

Feasible and effective

Ineffective or

unfeasible

Consider angioplasty/

Stent or surgery

No

Feasible and effective

Liver transplant

Ineffective or unfeasible

In BCS, patients with the Jak2V617F mutation had

a significantly more severe disease (Child-Pugh, Clichy

PI, Rotterdam score). Moreover, event free survival

tended to be decreased, but not significantly, in

patients with Jak2V617F mutation and significantly

decreased in MPD. However, at a median follow

up of 3.9 years, overall survival was not influenced

by either Jak2V617F mutation or MPD.26

The outcome of BCS with currently available

treatment is described in a prospective multi-center

study in which 163 patients were followed for a median of 17 mo (range 1-31 mo); 18% also had portal

vein thrombosis, 84% had a thrombophilic syndrome, 46% of which a myeloproliferative disorder

(MPD). Overall, 29 died, 8 for liver failure, 2 multiple organ failure, 2 bleeding. The 24 mo survival

was 82%. Prognostic factors were sex (male), ascites

and creatinine. Importantly, about 1/3 of the patients remained on medical therapy only.27 However,

the follow-up was not long enough to eventually

show the consequences of a slowly progressing disease, possibly prevented by early recanalization/decompression, and to draw any definitive conclusion

about the exact timing of treatment.

The long-term outcome of the same multicenter

experience was recently reported. Interestingly, 20

of the 69 who received only medical therapy died, a

high rate considering the availability of further invasive treatments. The remaining 88 underwent

invasive treatment, mostly TIPS, 20 LT, and only 3

surgical shunt. Overall survival was 74% at 5 years.28

One of the main unsolved issue of BCS management is probably timing of treatment. In fact,

Figure 1. A proposal of a new

algorithm for the management of

Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS).

although step-wise management suggests moving

forward when no response to therapy appears, definition for response to therapy was not stated1,2,29

and a proposal of such a definition needs validation.2 Moreover, because of the rarity of BCS, management guidelines come from expert opinion, are

empirical, and are not evidence based. Given that

benefit of treatments for BCS is not under debate,

anticipating invasive treatments, namely TIPS, before no response to medical therapy appears, could

perhaps decrease hepatic fibrosis development, disease progression, and finally improve outcome.29 In

conclusion, a proposal of a new algorithm of BCS

management suggesting early interventional therapy when clinical signs appear is reported (Figure 1).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE

I declare I have nothing to disclose

REFERENCES

1. DeLeve LD, Valla DC, Garcia-Tsao G. Vascular disorders of

the liver. Hepatology 2009; 49: 1729-64.

2. Plessier A, Sibert A, Consigny Y, Hakime A, Zappa M, Denninger MH, Condat B, et al. Aiming at minimal invasiveness

as a therapeutic strategy for Budd-Chiari syndrome. Hepatology 2006; 44: 1308-16.

3. Mancuso A. Budd-Chiari syndrome management: lights and

shadows. World J Hepatol 2011; 3: 262-4.

4. Bilbao JI, Pueyo JC, Longo JM, Arias M, Herrero JI, Benito

A, Barettino MD, et al. Interventional therapeutic techniques in Budd-Chiari syndrome. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol

1997; 20: 112-19.

5. Fisher NC, McCafferty I, Dolapci M, Wali M, Buckels JA,

Olliff SP, Elias E. Managing Budd-Chiari syndrome: a retros-

326

Mancuso A.

pective review of percutaneous hepatic vein angioplasty

and surgical shunting. Gut 1999; 44: 568-74.

6. Eapen CE, Velissaris D, Heydtmann M, Gunson B, Olliff S,

Elias E. Favourable medium term outcome following hepatic vein recanalisation and/or transjugular intrahepatic

portosystemic shunt for Budd Chiari syndrome. Gut 2006;

55: 878-84.

7. Perell A, Garca-Pagn JC, Gilabert R, Surez Y, Moitinho

E, Cervantes F, Reverter JC, et al. TIPS is a useful longterm derivative therapy for patients with Budd-Chiari

syndrome uncontrolled by medical therapy. Hepatology

2002; 35: 132-9.

8. Mancuso A, Fung K, Mela M, Tibballs J, Watkinson A,

Burroughs AK, Patch D. TIPS for acute and chronic BuddChiari syndrome: a single-centre experience. J Hepatol

2003; 38: 751-4.

9. Rssle M, Olschewski M, Siegerstetter V, Berger E, Kurz K,

Grandt D. The Budd-Chiari syndrome: outcome after

treatment with the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Surgery 2004; 135: 394-403.

10. Mancuso A, Watkinson A, Tibballs J, Patch D, Burroughs

AK. Budd-Chiari syndrome with portal, splenic, and superior mesenteric vein thrombosis treated with TIPS: who

dares wins. Gut 2003; 52: 438.

11. Darwish MS, Valla DC, De Groen PC, Zeitoun G, Haagsma

EB, Kuipers EJ, Janssen HL. Pathogenesis and treatment

of Budd-Chiari syndrome combined with portal vein thrombosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 83-90.

12. Garcia-Pagn JC, Heydtmann M, Raffa S, Plessier A, Murad

S, Fabris F, Vizzini G, et al. TIPS for Budd-Chiari syndrome:

long-term results and prognostics factors in 124 patients.

Gastroenterology 2008; 135: 808-15.

13. Ringe B, Lang H, Oldhafer KJ, Gebel M, Flemming P, Georgii

A, Borst HG, et al. Which is the best surgery for BuddChiari syndrome: venous decompression or liver transplantation? A single-center experience with 50 patients.

Hepatology 1995; 21: 1337-44.

14. Hemming AW, Langer B, Greig P, Taylor BR, Adams R,

Heathcote EJ. Treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome with

portosystemic shunt or liver transplantation. Am J Surg

1996; 171: 176-180; discussion 180-181.

15. Orloff MJ, Isenberg JI, Wheeler HO, Daily PO, Girard B.

Budd-Chiari syndrome revisited: 38 years experience

with surgical portal decompression. J Gastrointest Surg

2012; 16: 286-300; discussion 300.

16. Zhang Y, Zhao H, Yan D, Xue H, Lau WY. Superior mesenteric vein-caval-right atrium Y shunt for treatment of

Budd-Chiari syndrome with obstruction to the inferior

, 2014; 13 (3): 323-326

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

vena cava and the hepatic veins-a study of 62 patients. J

Surg Res 2011; 169: e93-e99.

Srinivas BC, Dattatreya PV, Srinivasa KH, Prabhavathi CN.

Inferior vena cava obstruction: long-term results of endovascular management. Indian Heart J 2012; 64: 162-9.

Mancuso A, Martinelli L, De Carlis L, Rampoldi AG, Magenta

G, Cannata A, Belli LS. A caval homograft for Budd-Chiari

syndrome due to inferior vena cava obstruction. World J

Hepatol 2013; 27: 292-5.

Halff G, Todo S, Tzakis AG, Gordon RD, Starzl TE. Liver

transplantation for the Budd-Chiari syndrome. Ann Surg

1990; 211: 43-9.

Rao AR, Chui AK, Gurkhan A, Shi LW, Al-Harbi I, Waugh R,

Verran DJ, et al. Orthotopic liver transplantation for

treatment of patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome: a Singecenter experience. Transplant Proc 2000; 32: 2206-207.

Ulrich F, Steinmller T, Lang M, Settmacher U, Mller AR,

Jonas S, Tullius SG, et al. Liver transplantation in patients

with advanced Budd-Chiari syndrome. Transplant Proc

2002; 34: 2278.

Srinivasan P, Rela M, Prachalias A, Muiesan P, Portmann B,

Mufti GJ, Pagliuca A, et al. Liver transplantation for BuddChiari syndrome. Transplantation 2002; 73: 973-7.

Mentha G, Giostra E, Majno PE, Bechstein WO, Neuhaus P,

OGrady J, Praseedom RK, et al. Liver transplantation for

Budd-Chiari syndrome: A European study on 248 patients

from 51 centres. J Hepatol 2006; 44: 520-8.

Segev DL, Nguyen GC, Locke JE, Simpkins CE, Montgomery

RA, Maley WR, Thuluvath PJ. Twenty years of liver transplantation for Budd-Chiari syndrome: a national registry

analysis. Liver Transpl 2007; 13: 1285-94.

Choi GS, Park JB, Jung GO, Chun JM, Kim JM, Moon JI,

Kwon CH, et al. Living donor liver transplantation in BuddChiari syndrome: a single-center experience. Transplant

Proc 2010; 42: 839-42.

Kiladjian JJ, Cervantes F, Leebeek FW, Marzac C, Cassinat B, Chevret S, Cazals-Hatem D, et al. The impact of

JAK2 and MPL mutations on diagnosis and prognosis

of splanchnic vein thrombosis: a report on 241 cases.

Blood 2008; 111: 4922-9.

Darwish MS, Plessier A, Hernandez-Guerra M, Fabris F,

Eapen CE, Bahr MJ, Trebicka J, et al. Etiology, management, and outcome of the Budd-Chiari syndrome. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 167-75.

Seijo S, Plessier A, Hoekstra J, DellEra A, Mandair D, Rifai

K, Trebicka J, et al. Good long-term outcome of Budd-Chiari syndrome with a step-wise management. Hepatology

2013; 57: 1962-8.

Mancuso A. Budd-Chiari Syndrome Management: Timing of

Treatment Is an Open Issue. Hepatology (IN PRESS).

También podría gustarte

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2104)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- Trasturel 440mg Anti CancerDocumento3 páginasTrasturel 440mg Anti CancerRadhika ChandranAún no hay calificaciones

- Jurnal Asli PBL 3 Blok 9Documento6 páginasJurnal Asli PBL 3 Blok 9Annisa FadilasariAún no hay calificaciones

- Futuristic Nursing: - Sister Elizabeth DavisDocumento14 páginasFuturistic Nursing: - Sister Elizabeth DavisPhebeDimple100% (2)

- Counseling: Counseling Is A Wonderful Twentieth-Century Invention. We Live in A Complex, BusyDocumento21 páginasCounseling: Counseling Is A Wonderful Twentieth-Century Invention. We Live in A Complex, BusyAnitha KarthikAún no hay calificaciones

- HHHHHGGGDocumento7 páginasHHHHHGGGemrangiftAún no hay calificaciones

- 11th Bio Zoology EM Official Answer Keys For Public Exam Mhay 2022 PDF DownloadDocumento3 páginas11th Bio Zoology EM Official Answer Keys For Public Exam Mhay 2022 PDF DownloadS. TAMIZHANAún no hay calificaciones

- My Evaluation in LnuDocumento4 páginasMy Evaluation in LnuReyjan ApolonioAún no hay calificaciones

- DLL - Mapeh 6 - Q4 - W6Documento4 páginasDLL - Mapeh 6 - Q4 - W6Bernard Martin100% (1)

- Philhealth Circular 013-2015Documento12 páginasPhilhealth Circular 013-2015Kim Patrick DayosAún no hay calificaciones

- MLC Lean Bronze Prep ClassDocumento2 páginasMLC Lean Bronze Prep ClassSalaAún no hay calificaciones

- 50 Maternal and Child NCLEX QuestionsDocumento14 páginas50 Maternal and Child NCLEX QuestionsShengxy Ferrer100% (2)

- AM LOVE School Form 8 SF8 Learner Basic Health and Nutrition ReportDocumento4 páginasAM LOVE School Form 8 SF8 Learner Basic Health and Nutrition ReportLornaNirzaEnriquezAún no hay calificaciones

- Professional Self ConceptDocumento11 páginasProfessional Self Conceptgladz25Aún no hay calificaciones

- Nursing Exam Questions With AnswerDocumento7 páginasNursing Exam Questions With AnswerjavedAún no hay calificaciones

- Soy Estrogen Myth False - DR Mercola Caught by Federal Authorities Spreading False Health Info - (Soy Found Not To Contain Estrogen, Soy Does Not Lower Men's Testosterone, Fraudulent Claims)Documento10 páginasSoy Estrogen Myth False - DR Mercola Caught by Federal Authorities Spreading False Health Info - (Soy Found Not To Contain Estrogen, Soy Does Not Lower Men's Testosterone, Fraudulent Claims)FRAUDWATCHCOMMISSIONAún no hay calificaciones

- 5.3.1 Distinguish Between Learning and Performance: Skill in SportDocumento48 páginas5.3.1 Distinguish Between Learning and Performance: Skill in SportAiham AltayehAún no hay calificaciones

- July 7, 2017 Strathmore TimesDocumento28 páginasJuly 7, 2017 Strathmore TimesStrathmore TimesAún no hay calificaciones

- Export of SpicesDocumento57 páginasExport of SpicesJunaid MultaniAún no hay calificaciones

- What Is FOCUS CHARTINGDocumento38 páginasWhat Is FOCUS CHARTINGSwen Digdigan-Ege100% (2)

- Using The Childrens Play Therapy Instrument CPTIDocumento12 páginasUsing The Childrens Play Therapy Instrument CPTIFernando Hilario VillapecellínAún no hay calificaciones

- Q3-Las-Health10-Module 3-Weeks 6-8Documento6 páginasQ3-Las-Health10-Module 3-Weeks 6-8MA TEODORA CABEZADAAún no hay calificaciones

- Know About Dengue FeverDocumento11 páginasKnow About Dengue FeverKamlesh SanghaviAún no hay calificaciones

- A Smart Gym Framework: Theoretical ApproachDocumento6 páginasA Smart Gym Framework: Theoretical ApproachciccioAún no hay calificaciones

- Net Jets Pilot & Benefits PackageDocumento4 páginasNet Jets Pilot & Benefits PackagedtoftenAún no hay calificaciones

- A Study To Assess The Effectiveness of Selected Teaching Strategies Knowledge Regarding Drug Calculation Among B.Sc. N Students in Selected College at ChennaiDocumento3 páginasA Study To Assess The Effectiveness of Selected Teaching Strategies Knowledge Regarding Drug Calculation Among B.Sc. N Students in Selected College at ChennaiEditor IJTSRDAún no hay calificaciones

- 2011 Member Handbook English UHCCPforAdults NYDocumento52 páginas2011 Member Handbook English UHCCPforAdults NYpatsan89Aún no hay calificaciones

- Module 11 Rational Cloze Drilling ExercisesDocumento9 páginasModule 11 Rational Cloze Drilling Exercisesperagas0% (1)

- Pitbull StatementDocumento4 páginasPitbull StatementThe Citizen NewspaperAún no hay calificaciones

- R4 HealthfacilitiesDocumento332 páginasR4 HealthfacilitiesCarl Joseph BarcenasAún no hay calificaciones

- 2011 Urine Therapy J of NephrolDocumento3 páginas2011 Urine Therapy J of NephrolCentaur ArcherAún no hay calificaciones