Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Acute Post-Op Pain Management

Cargado por

1234chocoTítulo original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Acute Post-Op Pain Management

Cargado por

1234chocoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

OKA5301 NPS APOP EVC.

qxd

16/2/07

3:13 PM

Page 1

Acute postoperative

pain management

Optimal postoperative pain management

begins in the preoperative period

Measure pain regularly using a validated

pain assessment tool

Pain is subjective and each individual patients experience of pain is different.

Reasons for these differences include:

Regular and routine assessment of pain will result in improved pain management.1

age

The patients own assessment of pain is the most reliable and should be used

when possible.1

co-morbidities including chronic pain

Use a pain measurement tool appropriate to patients mental status, age and language.

concurrent medication and other substance intake

Measure pain scores both at rest and on movement/function to assess the impact

on functional activity.13

mechanisms of pain nociceptive, neuropathic

Re-assess pain regularly and before/after administering analgesia or other pain

management strategies.

modifying factors e.g. mood, cognition, coping strategies

genetics.

Document pain assessment measurements as part of routine observations.

Conduct preoperative patient evaluation:

Validated pain assessment tools

Ask the patient and/or their carers to help establish pain history (consider the above).

Patient measures

Document in the patients medical record, otherwise state that there are

no relevant factors.

Visual analogue scale (VAS; figure 1).

Numerical rating scale (NRS; figure 2).

Discuss pain management strategies and expectations in the preoperative period.

Verbal descriptor scale e.g. none/mild/moderate/severe.

WongBaker faces scale (figure 3).

Observer measures

Behavioural pain scale.3

Fig 1: Visual analogue scale

Fig 2: Numerical rating scale

Fig 3: WongBaker faces scale

PAIN SCORE 0 10 NUMERICAL RATING

010 Numerical Rating Scale

No

Pain

Worst

Pain Ever

No

Pain

4

5

6

Moderate Pain

Worst

Possible

10 Pain

10

No Hurt

Hurts

Little Bit

Hurts

Little More

Hurts

Even More

Hurts

Whole Lot

Hurts

Worst

WongBaker FACES Pain Rating Scale, from Wong DL et al.: Whaley and

Wongs Essentials of Pediatric Nursing, 5th edition, St. Louis, 2001, Mosby, p. 1301.

http://www.mosbysdrugconsult.com/WOW/facesReproductions.html (accessed 31 January 2007).

APOP Project

OKA5301 NPS APOP EVC.qxd

16/2/07

3:13 PM

Page 2

Ensure all postoperative patients receive safe and effective analgesia

When prescribing analgesia

Routes of administration:

Use a variety of approaches (multimodal analgesia) to improve analgesia and decrease

doses of individual agents.4

Paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are valuable components

of multimodal analgesia.1

Use intermittent intravenous (IV) opioids to gain initial control of severe pain,

as IV administration provides rapid and reliable drug absorption.1

(Note: prescription of nurse-administered IV opioids is not recommended for

ongoing analgesia on general wards.)

When using analgesics on a regular basis have additional prn medication available for

breakthrough pain.

Consider subcutaneous route for ongoing parenteral opioids, avoid intramuscular route

(painful and less predictable absorption).1

Use individualised doses of analgesic(s) administered at appropriate dose intervals and

titrate to patient response.4

Once the oral route has been established, use when possible.1

Drug class

Considerations

Selected precautions

Paracetamol

Useful adjunctive analgesic agent

Provide clear directions when prescribing >1 paracetamol-containing preparation

Consider regular order rather than prn

When combined with opioids, increases pain relief1

Maximum 4 g daily dose usually recommended in healthy adults;

reduce dose in malnourished, underweight patients

Regular (1 g every 46 hours) use can reduce opioid requirements by 2030%1

Avoid in severe liver dysfunction

Only prescribe IV (avoid rectal) if oral is inappropriate1

NSAIDs

(e.g. conventional: ibuprofen,

COX-2 selective: celecoxib)

Tramadol

Opioids

(e.g. morphine,

oxycodone, fentanyl, hydromorphone,

pethidine, dextropropoxyphene)

Adjunctive analgesics for use with opioids

and/or paracetamol1

Adverse effects of NSAIDs are significant; may limit use1

Inadequate for severe pain when given alone,

but can reduce opioid requirements1

Modify dose or avoid in congestive heart failure, those at risk of renal effects

(renal disease, hypovolaemia, hypotension, concurrent use of other nephrotoxic

agents), the elderly

Limit prescription to two to three days then review4

Lower risk of GI bleeding or ulcers with COX-2 selective NSAIDs1

Weak opioid with serotonergic and noradrenergic effects, as effective as morphine

for some types of moderate postoperative pain, less so for severe acute pain5

Avoid in patients with history of seizures

Less risk of respiratory depression and constipation1,5

Be aware of rare, but potentially serious, drug interactions with SSRIs, TCAs,

pethidine, warfarin, St Johns wort

Prescribe opioid dose based on age, use lower initial dose in the elderly

and titrate upwards5

Prescribing multiple opioids via multiple routes increases risk of opioid overdose

and is generally not recommended

Be aware of potential for prescribing and administration errors with immediate

and sustained-release preparations

Do not use morphine or pethidine in severe renal impairment5

Be aware of factors that may increase risk of opioid overdose (e.g. concurrent

sedatives, opioid nave, sepsis)

Use with caution in severe renal impairment and the elderly

Avoid pethidine (accumulation of toxic metabolite norpethidine, drug interactions)

and dextropropoxyphene (unsafe in overdose, ceiling effect)

Abbreviations: ACEI = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, NSAIDs = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, SSRIs = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, TCAs = tricyclic antidepressants.

OKA5301 NPS APOP EVC.qxd

16/2/07

3:13 PM

Page 3

Monitor and manage adverse events

Monitoring respiratory depression and sedation

(patients on opioids sedatives)

Respiratory rate alone as an indicator of respiratory depression is of limited value

and hypoxaemic episodes may occur in the absence of a reduced respiratory rate.1

Sedation scores are a more reliable indicator respiratory depression is almost always

preceded by sedation.6 The sedation score measures the patients level of wakefulness

and their ability to respond appropriately to verbal command. A four-point scale3

(box 1) is recommended.

Box 1: Sedation scoring

Sedation score

Suggested action

Awake, alert

Mild sedation

1S

Asleep

Moderate sedation, easy to rouse

but unable to stay awake

Monitoring nausea and vomiting

Easy to rouse

Effective antiemetics in the postoperative period include 5HT3 antagonists, droperidol

and dexamethasone.4

Consider co-prescribing more than one antiemetic, each with a different mechanism

of action, with instructions to add a drug from a different class if the first agent is

ineffective.7

Monitoring for other adverse events

Regular review will reduce the risk of serious side effects developing and will allow

for adjustment of doses, dosage interval and alteration of analgesics as necessary.

Side effects for the following include:

Continue routine monitoring

Consider reducing analgesic dose,

increase frequency of monitoring

If respiratory rate < 8 breaths per minute,

withhold opioid, administer naloxone

and notify medical officer

Difficult to rouse, unable to stay awake

Withhold opioid, administer naloxone

and notify medical officer

Note that naloxone should be administered

IV in divided doses of not greater than

100 micrograms

Opioids constipation (consider prescribing of prophylactic laxatives),

urinary retention, itch, confusion and postural hypotension.

NSAIDs GI (peptic ulceration), renal (monitor renal function e.g. in renally impaired

patients, and those being treated with ACEIs, diuretics and aminoglycoside antibiotics),

bronchospasm, platelet inhibition (increased blood loss).1 Risk and severity of side effects

is generally increased in the elderly.1

APOP Project

OKA5301 NPS APOP EVC.qxd

16/2/07

3:13 PM

Page 4

Communicate ongoing pain management plan to both patients

and primary healthcare professionals at discharge

There is evidence of gaps in discharge planning leading to significant harm.8

A pain management plan, as a component of discharge planning, should be clearly

communicated to the patient and/or their carer, general practitioner and other communitybased health professionals.

Management action:

A pain management plan is essential for patients at increased risk of pain after discharge

(see below). This is likely to improve the patients post-discharge pain experience, utilisation

of outpatient services and prevent surgical complications.9

Prescribe drugs for symptomatic relief of side effects where necessary

(e.g. antiemetics and laxatives).

Review analgesia requirements and consider relevant risk factors 24 hours

before discharge.

If prescribing a strong opioid, consider limiting quantity prescribed.

Pain management plan8 at discharge includes:

Factors associated with increased risk of pain and/or complexity of analgesic

requirements post-discharge*:

Patient characteristics5 age, debilitated, cognitive impairment, severe liver disease, renal

impairment, peptic ulcer disease, chronic pain or low pain threshold, multiple admissions

for pain, obstetric patients.

Surgery types1 thoracic, abdominal surgery, surgery involving major disruption of

muscle, bone or nervous tissue, bone grafts.

Concurrent medicines5 opioid antagonists, chronic opioids, SSRIs, monoamine oxidase

inhibitors, central nervous system depressants, warfarin, St Johns wort, ACEIs, diuretics.

*Consult Acute Pain Service or Pain Specialist where necessary (if available).

A list of all analgesics, with dosage and administration times.

Instructions on anticipated/intended duration of therapy and reducing/ceasing therapy

where appropriate.

Important consumer-specific medicines information (e.g. adverse reactions including

allergies, drug interactions, ceased medicines).

For paracetamol-containing analgesics, give (written) information about safe use,

including maximum daily dose of paracetamol.

Instructions for monitoring and managing side effects.5

Methods to improve function while recovering including non-pharmacological methods

for relieving pain.

Contact person for pain problems (uncontrolled or persistent pain) and other

postoperative concerns (e.g. bleeding and infections).

References:

1.

Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA).

Acute pain management: Scientific evidence, 2nd edition. ANZCA, 2005.

http://www.anzca.edu.au/publications/acutepain.htm (accessed 31 January 2007).

3.

Acute pain management performance toolkit. Melbourne: Victorian Quality Council, 2007.

http://www.health.vic.gov.au/qualitycouncil/activities/acute.htm

(accessed 31 January 2007)

2.

Clinical practice guideline for the management of postoperative pain. Version 1.2.

Washington, DC: Department of Defense, Veterans Health Administration, 2002.

http://www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=3284

(accessed 31 January 2007).

4.

Therapeutic Guidelines: Analgesic, Version 4. 2002.

5.

Australian Medicines Handbook, 2007.

6.

Macintyre PE, Schug SA. Acute Pain ManagementA Practical Guide, 3rd edition, 2007

(in press).

7.

Habib AS, Gan TJ. Evidence-based management of postoperative nausea and vomiting:

a review. Can J Anaesth 2004;51:32641.

8.

Australian Pharmaceutical Advisory Council. Guiding principles to achieve continuity

in medication management. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2005.

http://www.health.gov.au/internet/wcms/publishing.nsf/Content/nmp-guiding

(accessed 31 January 2007)

9.

Kable A, Gibberd R, Spigelman A. Complications after discharge for surgical patients.

ANZ J Surg 2004;74:9297.

Drug Use Evaluation project conducted by the APOP study group: Victorian Department of Human Services/Victorian Drug Usage Evaluation Group; UMORE, Tasmanian School of Pharmacy, University of Tasmania;

South Australian Therapeutic Advisory Group/Department of Health; School of Pharmacy, University of Queensland; New South Wales Therapeutic Advisory Group. Funded and supported by the National Prescribing Service Limited (02 8217 8700).

For more information on the management of postoperative pain refer to ANZCA Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence, 2nd edition, 2005, and Therapeutic Guidelines: Analgesic, Version 4, 2002.

The information contained in this material is derived from a critical analysis of a wide range of authoritative evidence. Any treatment decisions based on this information should be made in the context of the individual clinical

circumstances of each patient. Reviewed by: Dr C Roger Goucke, Dr Jane Trinca, Dr Pamela E Macintyre, Professor Stephan A Schug, Faculty of Pain Medicine, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists.

February 2007

NPSE0396_FEB_2007

También podría gustarte

- Treatment of Resistant and Refractory HypertensionDocumento21 páginasTreatment of Resistant and Refractory HypertensionLuis Rodriguez100% (1)

- Dr. Alurkur's Book On Cardiology - 2Documento85 páginasDr. Alurkur's Book On Cardiology - 2Bhattarai ShrinkhalaAún no hay calificaciones

- Getting the Hospital Job: A Step-by-Step Guide to Applying for Your First PositionDocumento41 páginasGetting the Hospital Job: A Step-by-Step Guide to Applying for Your First Position1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Intravenous Fluid Therapy in Adults in Hospital Algorithm Poster Set 191627821Documento5 páginasIntravenous Fluid Therapy in Adults in Hospital Algorithm Poster Set 191627821crsscribdAún no hay calificaciones

- Managing Psychiatric Patients in The EDDocumento28 páginasManaging Psychiatric Patients in The EDfadiAún no hay calificaciones

- Opioid Analgesics: Mechanisms of Action and Clinical UsesDocumento20 páginasOpioid Analgesics: Mechanisms of Action and Clinical UsesRichard100% (1)

- Sinus ArrhythmiaDocumento6 páginasSinus ArrhythmiaVincent Maralit MaterialAún no hay calificaciones

- Prescribing Medicine in Pregnancy, by Australian Drug Evaluation CommitteeDocumento90 páginasPrescribing Medicine in Pregnancy, by Australian Drug Evaluation Committee徐承恩100% (1)

- Peripheral Artery Occlusive Disease: What To Do About Intermittent Claudication??Documento46 páginasPeripheral Artery Occlusive Disease: What To Do About Intermittent Claudication??Dzariyat_Azhar_9277100% (1)

- Anti-Anginal DrugsDocumento39 páginasAnti-Anginal Drugspoonam rana100% (1)

- A Simple Guide to Hypovolemia, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsDe EverandA Simple Guide to Hypovolemia, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsAún no hay calificaciones

- Drugs in Cardiac EnmergenciesDocumento94 páginasDrugs in Cardiac EnmergenciesVijayan VelayudhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Metoprolol Teaching PlanDocumento18 páginasMetoprolol Teaching Planapi-419091662Aún no hay calificaciones

- Pain Management in Infants - Children - AdolescentsDocumento9 páginasPain Management in Infants - Children - AdolescentsOxana Turcu100% (1)

- Clinical Handover Ian ScottDocumento26 páginasClinical Handover Ian ScottYwagar YwagarAún no hay calificaciones

- Psychiatric and Behavioral Aspects of Epilepsy: Nigel C. Jones Andres M. Kanner EditorsDocumento352 páginasPsychiatric and Behavioral Aspects of Epilepsy: Nigel C. Jones Andres M. Kanner EditorsDAVID100% (1)

- TLS FinalDocumento69 páginasTLS FinalGrace Arthur100% (1)

- Cyanotic Spell: Dr. Shirley L A, Sp. A 12 April 2011Documento6 páginasCyanotic Spell: Dr. Shirley L A, Sp. A 12 April 2011Kahfi Rakhmadian KiraAún no hay calificaciones

- USMLE Flashcards: Anatomy - Side by SideDocumento190 páginasUSMLE Flashcards: Anatomy - Side by SideMedSchoolStuff100% (3)

- Hypertension Treatment Steps For HypertensionDocumento15 páginasHypertension Treatment Steps For Hypertensionfreelancer08100% (1)

- Howlett and Ramesh Educational Policy ModelDocumento11 páginasHowlett and Ramesh Educational Policy ModelJaquelyn Montales100% (1)

- FIRST AID by Dr. Qasim AhmedDocumento80 páginasFIRST AID by Dr. Qasim AhmedFaheem KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Antifungal Drugs: - Polyene Antibiotics: Amphotericin B, Nystatin - Antimetabolites: 5-Fluorocytosine - AzolesDocumento18 páginasAntifungal Drugs: - Polyene Antibiotics: Amphotericin B, Nystatin - Antimetabolites: 5-Fluorocytosine - AzolesgopscharanAún no hay calificaciones

- Hypertensive Crisis: Megat Mohd Azman Bin AdzmiDocumento34 páginasHypertensive Crisis: Megat Mohd Azman Bin AdzmiMegat Mohd Azman AdzmiAún no hay calificaciones

- Fluid N Electrolyte BalanceDocumento60 páginasFluid N Electrolyte BalanceAnusha Verghese67% (3)

- Pain ManagementDocumento78 páginasPain ManagementKiran100% (1)

- At2-Bsbsus411 (2) Done 29Documento15 páginasAt2-Bsbsus411 (2) Done 29DRSSONIA11MAY SHARMAAún no hay calificaciones

- ECMO and Right Ventricular FailureDocumento9 páginasECMO and Right Ventricular FailureLuis Fernando Morales JuradoAún no hay calificaciones

- Language of PreventionDocumento9 páginasLanguage of Prevention1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Working Like A Scientist Grade 8Documento26 páginasWorking Like A Scientist Grade 8Therese D'Aguillar100% (1)

- Asthma 160424141552Documento54 páginasAsthma 160424141552almukhtabir100% (1)

- Standard Treatment GuidelinesDocumento5 páginasStandard Treatment Guidelinesbournvilleeater100% (1)

- Intravenous Fluid Therapy - Knowledge For Medical Students and PhysiciansDocumento6 páginasIntravenous Fluid Therapy - Knowledge For Medical Students and PhysiciansNafiul IslamAún no hay calificaciones

- Intravenous FluidsDocumento3 páginasIntravenous FluidsKristine Artes AguilarAún no hay calificaciones

- Maged 2015Documento185 páginasMaged 2015engy6nagyAún no hay calificaciones

- Standard Treatment WorkflowsDocumento75 páginasStandard Treatment WorkflowsIndranil DuttaAún no hay calificaciones

- 2020 Intravenous Fuid TherapyDocumento19 páginas2020 Intravenous Fuid TherapyDaniela MéndezAún no hay calificaciones

- Management of Hypertension in CKD 2015Documento9 páginasManagement of Hypertension in CKD 2015Alexander BallesterosAún no hay calificaciones

- IPHS Guidelines Health Centres PDFDocumento92 páginasIPHS Guidelines Health Centres PDFAnuradha YadavAún no hay calificaciones

- Aldrete'sDocumento1 páginaAldrete'sKarlston LapnitenAún no hay calificaciones

- Essential HypertensionDocumento13 páginasEssential HypertensionIvan KurniadiAún no hay calificaciones

- PalliationDocumento16 páginasPalliationPartha ChakrabortyAún no hay calificaciones

- Rational Drug Prescribing Training CourseDocumento78 páginasRational Drug Prescribing Training CourseAhmadu Shehu MohammedAún no hay calificaciones

- Safety PharmacologyDocumento20 páginasSafety PharmacologyPranjal KothaleAún no hay calificaciones

- Advanced Cardiac Life SupportDocumento37 páginasAdvanced Cardiac Life SupportRoy Acosta GumbanAún no hay calificaciones

- Drug Compliance Among Hypertensive PatientsDocumento5 páginasDrug Compliance Among Hypertensive PatientsSyifa MunawarahAún no hay calificaciones

- Principles of Fluid ManagementDocumento17 páginasPrinciples of Fluid ManagementBrainy-Paykiesaurus LuminirexAún no hay calificaciones

- Makalah HypertensionDocumento6 páginasMakalah HypertensionFatin ZafirahAún no hay calificaciones

- Pharmacotherapy of StrokeDocumento37 páginasPharmacotherapy of StrokeAndykaYayanSetiawanAún no hay calificaciones

- ICU-Procedural 1st YearDocumento3 páginasICU-Procedural 1st YearNephrology On-DemandAún no hay calificaciones

- Neurologic Assessment RationaleDocumento16 páginasNeurologic Assessment RationaleflorenzoAún no hay calificaciones

- Drugs Affecting Myometrium1 PDFDocumento9 páginasDrugs Affecting Myometrium1 PDFЛариса ТкачеваAún no hay calificaciones

- Nurse PicuDocumento5 páginasNurse PicuDitto RezkiawanAún no hay calificaciones

- Medicine CPDocumento127 páginasMedicine CPDipesh ShresthaAún no hay calificaciones

- Critical Care Update PDFDocumento25 páginasCritical Care Update PDFHugo PozoAún no hay calificaciones

- World Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences Review ArticleDocumento12 páginasWorld Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences Review Articlevikas vermaAún no hay calificaciones

- Hypertensive Emergencies (ESC 2019)Documento10 páginasHypertensive Emergencies (ESC 2019)Glen LazarusAún no hay calificaciones

- Cardiac ValveDocumento12 páginasCardiac ValveHellen WestgroveAún no hay calificaciones

- Intravenous (IV) InfusionDocumento16 páginasIntravenous (IV) InfusionSiti Rukayah100% (1)

- Biostatistics Community Medicine Gomal Medical College NotesDocumento22 páginasBiostatistics Community Medicine Gomal Medical College Notesjay_p_shah0% (1)

- Acute vs Chronic Pain: Key DifferencesDocumento20 páginasAcute vs Chronic Pain: Key DifferencessukunathAún no hay calificaciones

- Coagulation: Bleeding TimeDocumento6 páginasCoagulation: Bleeding TimeimperiouxxAún no hay calificaciones

- Ayurvedic Insights of Avascular Necrosis of Femoral HeadDocumento4 páginasAyurvedic Insights of Avascular Necrosis of Femoral HeadIJAR JOURNALAún no hay calificaciones

- Safeguards for Reducing Errors with High Alert MedicationsDocumento27 páginasSafeguards for Reducing Errors with High Alert MedicationsnovitalumintusariAún no hay calificaciones

- Managing Acute Pain in Opioid-Tolerant PatientsDocumento6 páginasManaging Acute Pain in Opioid-Tolerant PatientsHendrikus Surya Adhi PutraAún no hay calificaciones

- Pemantauan Dan Penanganan Nyeri Pasca BedahDocumento42 páginasPemantauan Dan Penanganan Nyeri Pasca BedahAkbar Muitan LantauAún no hay calificaciones

- Pokemon Theme Song 22Documento4 páginasPokemon Theme Song 221234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- # 3 - Prospective Study of The Diagnostic Accuracy of The Simplify D-Dimer Assay For Pulmonary Embolism in EDDocumento7 páginas# 3 - Prospective Study of The Diagnostic Accuracy of The Simplify D-Dimer Assay For Pulmonary Embolism in ED1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Code Geass - StoriesDocumento5 páginasCode Geass - Stories1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Blue Veins Sub Theme TVBDocumento4 páginasBlue Veins Sub Theme TVB1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Topical Steroids (Sep 19) PDFDocumento7 páginasTopical Steroids (Sep 19) PDF1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Mbs Quick Guide: JULY 2020Documento2 páginasMbs Quick Guide: JULY 20201234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- QLD Rail Traim PDFDocumento1 páginaQLD Rail Traim PDF1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Fairy Tail - Main ThemeDocumento3 páginasFairy Tail - Main Theme1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Osteo Infographic FinalDocumento1 páginaOsteo Infographic Final1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Doctor Talk: Communication Practice Role PlaysDocumento6 páginasDoctor Talk: Communication Practice Role Plays1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Fluids ElectrolytesDocumento2 páginasFluids Electrolytes1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Blue BirdDocumento7 páginasBlue Bird1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Topical Steroids (Sep 19) PDFDocumento7 páginasTopical Steroids (Sep 19) PDF1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

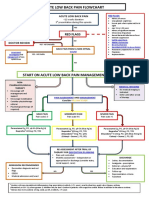

- Acute Low Back Pain Flowchart January 2017Documento1 páginaAcute Low Back Pain Flowchart January 20171234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- PBM Module1 MTP Template 0Documento2 páginasPBM Module1 MTP Template 01234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- VTE GuidelinesDocumento11 páginasVTE Guidelines1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Managing Mental Illness in Patients From CALD Backgrounds: PsychiatryDocumento5 páginasManaging Mental Illness in Patients From CALD Backgrounds: Psychiatry1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Taking a Social and Cultural History: A Biopsychosocial ApproachDocumento3 páginasTaking a Social and Cultural History: A Biopsychosocial Approach1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- 2016 Applicant Guide Web V2Documento83 páginas2016 Applicant Guide Web V21234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Metro South Intern Training Form (Logan)Documento3 páginasMetro South Intern Training Form (Logan)1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- FLOWCHART - ARC Adult Cardiorespiratory ArrestDocumento1 páginaFLOWCHART - ARC Adult Cardiorespiratory Arrest1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- The Effects of Social Networks On Disability in Older AustraliansDocumento22 páginasThe Effects of Social Networks On Disability in Older Australians1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Herd Immunity'' A Rough Guide PDFDocumento6 páginasHerd Immunity'' A Rough Guide PDF1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- ImprovingMedAdherenceOlderAdultslyer Final 508CDocumento2 páginasImprovingMedAdherenceOlderAdultslyer Final 508CKumar PatilAún no hay calificaciones

- Clinical Contributions To Addressing The Social Determinants of HealthDocumento5 páginasClinical Contributions To Addressing The Social Determinants of Health1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Defining and Assessing Risks To Health PDFDocumento20 páginasDefining and Assessing Risks To Health PDF1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- A Conceptual Framework For HealthDocumento1 páginaA Conceptual Framework For Health1234chocoAún no hay calificaciones

- Frcpath Part 1 Previous Questions: Document1Documento11 páginasFrcpath Part 1 Previous Questions: Document1Ali LaftaAún no hay calificaciones

- Limulus Amebocyte Lysate Test (LAL)Documento16 páginasLimulus Amebocyte Lysate Test (LAL)Shahriar ShamimAún no hay calificaciones

- De Luyen Thi TNTHPT (6) - HsDocumento5 páginasDe Luyen Thi TNTHPT (6) - HsPhương Quang Nguyễn LýAún no hay calificaciones

- Male, Masculinities Methodologies and MethodsDocumento40 páginasMale, Masculinities Methodologies and MethodsMarco Rojas VAún no hay calificaciones

- GSGMC Department Vacancies by SpecialtyDocumento6 páginasGSGMC Department Vacancies by SpecialtyRajaAún no hay calificaciones

- Reasons for Conducting Qualitative ResearchDocumento12 páginasReasons for Conducting Qualitative ResearchMa. Rhona Faye MedesAún no hay calificaciones

- Healing Wonders AppDocumento18 páginasHealing Wonders AppJoanna Atrisk C-LealAún no hay calificaciones

- Speech by SakiDocumento2 páginasSpeech by Sakiapi-516439363Aún no hay calificaciones

- 3710Documento9 páginas3710Asad KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Dialysis Report - NURS 302Documento3 páginasDialysis Report - NURS 302AmalAún no hay calificaciones

- COBADocumento222 páginasCOBArendiAún no hay calificaciones

- Google CL Ebony ThomasDocumento2 páginasGoogle CL Ebony Thomasebony thomasAún no hay calificaciones

- Task 2 Case Notes: James Hutton: Time AllowedDocumento3 páginasTask 2 Case Notes: James Hutton: Time AllowedKelvin Kanengoni0% (1)

- Sublingual Sialocele in A Cat: Jean Bassanino, Sophie Palierne, Margaux Blondel and Brice S ReynoldsDocumento5 páginasSublingual Sialocele in A Cat: Jean Bassanino, Sophie Palierne, Margaux Blondel and Brice S ReynoldsTarsilaRibeiroMaiaAún no hay calificaciones

- Full Download Contemporary Nutrition A Functional Approach 4th Edition Wardlaw Solutions ManualDocumento36 páginasFull Download Contemporary Nutrition A Functional Approach 4th Edition Wardlaw Solutions Manualalojlyhol3100% (33)

- WiproDocumento14 páginasWipromalla srujanaAún no hay calificaciones

- Sports Injuries - StrainDocumento10 páginasSports Injuries - StrainChris SinugbojanAún no hay calificaciones

- Stress Eating: A Phenomenological StudyDocumento24 páginasStress Eating: A Phenomenological StudyGauis Laurence CaraoaAún no hay calificaciones

- Goal Planning and Neurorehabilitation: The Wolfson Neurorehabilitation Centre ApproachDocumento13 páginasGoal Planning and Neurorehabilitation: The Wolfson Neurorehabilitation Centre ApproachMiguelySusy Ramos-RojasAún no hay calificaciones

- The Nigerian National Health Policy and StructureDocumento24 páginasThe Nigerian National Health Policy and StructureofficialmidasAún no hay calificaciones

- TLE8 Q0 Mod5 Cookery v2Documento14 páginasTLE8 Q0 Mod5 Cookery v2Lauro Jr. AtienzaAún no hay calificaciones

- History of Movement EducationDocumento4 páginasHistory of Movement EducationMark FernandezAún no hay calificaciones

- Folder - Farming Insects - 2Documento2 páginasFolder - Farming Insects - 2Paulin NanaAún no hay calificaciones

- Pediatric Concept MapDocumento6 páginasPediatric Concept Mapapi-507427888Aún no hay calificaciones

- KHDA - Dar Al Marefa School 2016-2017Documento27 páginasKHDA - Dar Al Marefa School 2016-2017Edarabia.comAún no hay calificaciones

- RS5312 Assignment Analyzes Low Back Pain Case Using GuidelinesDocumento9 páginasRS5312 Assignment Analyzes Low Back Pain Case Using GuidelinesCelina Tam Ching LamAún no hay calificaciones