Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

AG Jim Hood Opposition Motion On Discovery/Privilege Log

AG Jim Hood Opposition Motion On Discovery/Privilege Log

Cargado por

Russ LatinoDescripción original:

Título original

Derechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

AG Jim Hood Opposition Motion On Discovery/Privilege Log

AG Jim Hood Opposition Motion On Discovery/Privilege Log

Cargado por

Russ LatinoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 1 of 22

IN THE UNITED STATES DISRTICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI

NORTHERN DIVISION

GOOGLE, INC.

V.

PLAINTIFF

CIVIL ACTION NO. 3:14-CV-981-HTW-LRA

JIM HOOD, in his official capacity

as Attorney General of the State of

Mississippi

DEFENDANT

______________________________________________________________________________

ATTORNEY GENERALS MEMORANDUM IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION

TO COMPEL THE PRODUCTION OF DOCUMENTS

______________________________________________________________________________

Attorney General Jim Hood, in his official capacity (the Attorney General or

General Hood), files this Response in Opposition to Google, Inc.s (Google)

Motion to Compel the Production of Documents [Doc. No. 100]. For the reasons set

forth below, Googles motion should be denied.1

I.

Introduction

A.

History and Background Leading to Issuance of Subpoena

Googles lawsuit in general and its motion to compel in particular

misapprehends the nature in which this case arose. Google well knows and the

record before this Court clearly reflects, that prior to the issuance of the disputed

Googles Motion to Compel does not comply with L. U. Civ. R. 7(b)(4) which provides that

[a]t the time the motion is served, other than motions or applications that may be heard ex parte or

those involving necessitous or urgent matters, counsel for the movant must file a memorandum brief

in support of the motion. Id. The instant motion is not one to be heard ex parte nor does it involve

a necessitous or urgent and Google did not file a memorandum nor did it seek relief from the

requirements of the Local Rule. This is notable, in part, because Google throughout its motion

argues that the Attorney Generals Supplemental Privilege Log does not conform to the requirements

of L. U. Civ. R. 26(a)(1)(C), which the Attorney General contests. However, Googles selective

invocation of the Local Rules should be taken with a grain of salt.

1

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 2 of 22

Subpoena in this case, a number of Attorneys General were looking into certain of

Googles business practices under various state consumer protection laws. For

example in February 2013, Attorneys General from Hawaii, Mississippi, and

Virginia wrote to search engines, including Google, regarding concern[ ] about the

infringing activities[ ] [i]n addition to the economic impact, the sale of counterfeit

products clearly places the consumers health and safety at risk. [Doc. No. 33-4].

The letter stated that the Director of Immigration and Custom Enforcement

provided chilling examples of the harm that can be inflicted by such products. Id.

In March 2013, Google entered into an Assurance of Voluntary Compliance

(Compliance Agreement) as part of a multi-state investigation by State Attorneys

General, including General Hood. [Doc. No. 33-5, Ex. 1]. Thirty-seven states,

including Mississippi, joined the Compliance Agreement. This Compliance

Agreement related to Googles Street View product whereby Google outfitted its

Street View cars with antennae to drive down public streets and collect WiFi

network identification for use in offering location aware or geolocation services.

Id. As part of the Compliance Agreement, Google agreed to both refrain from

certain conduct as well as take affirmative steps. See, id p. 5. Google paid

$7,000,000 apportioned among the states signing on to the Compliance Agreement.

Id.

In July 2013, Attorneys General from Nebraska and Oklahoma wrote to

Googles Senior Vice President and General Counsel regarding an alarming trend

involving videos on Googles video subsidiary, YouTube. [Doc. No. 33-6]. The July

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 3 of 22

2014 letter further stated that [a]s we understand the process, video producers are

asked prior to posting whether they will allow YouTube to host advertising with the

video and, for those who consent, the advertising revenue is shared between the

producer and Google. Id. at 1. While this practice itself is not troubling we were

disappointed to learn that many such monetized videos posted to YouTube depict or

even promote dangerous or illegal activities. Id. The letter to Google went on to

cite specific examples of these concerns. Id.

In October 2013, Attorneys General from Nebraska, Hawaii, Virginia and

General Hood wrote to Googles Senior Vice President for Corporate Development to

address the monetization of dangerous and illegal content. [Doc. No. 33-7].

Attorney General Bruning of Nebraska, Attorney General Louie of Hawaii and

Attorney General Cuccinelli of Virginia, as well as General Hood stated that [a]s

you are no doubt aware, several state Attorneys General have expressed concerns

regarding your companys monetization of dangerous and illegal content,

particularly on Googles video subsidiary, YouTube. Id. (emphasis supplied).

The letter further raised concerns regarding the prevalence of content on

Googles platforms which constitute intellectual property violations and within

which such content is shared and trafficked over Googles systems. Id. at p. 1.

These Attorneys General raised other concerns to Google in this letter including the

promotion of illegal and prescription-free drugs through Google and the facilitation

of payments to and by purveyors of all the aforementioned content through Googles

payment services. Id.

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 4 of 22

In November 2013, Google entered into another Assurance of Voluntary

Compliance Agreement with thirty-seven (37) states and the District of Columbia.

[Doc. No. 33-5, Ex. 2]. The November Compliance Agreement stemmed from

Googles posting of certain information to Apples Safari Browser. Id. The

November 8 Compliance Agreement provided that Google shall not employ HTTP

Form POST functionality that uses javascript to submit a form without affirmative

user action for the purposes of overriding a Browers Cookie-blocking settings so

that it may palace an HTTP Cookie on such Browser, without that users prior

consent. Id. at 2. Google paid $17,000,000 apportioned among the states and the

District of Columbia joining in the Compliance Agreement. Id. at 4.

In December 2013, twenty-three (23) Attorneys General, including General

Hood, wrote to Googles general counsel again stating that [d]uring the past year, a

growing number of state Attorneys General have expressed concerns regarding the

troubling and harmful problems posed by several of Googles products. [Doc. No. 338]. As expressed by these twenty-three Attorneys General, these issues included:

(1) Googles monetization of dangerous and illegal content; (2) the prevalence of

content constituting intellectual property violations and ease with which such

content is shared and trafficked over Googles systems; (3) the promotion of illegal

and prescription-free drugs; and (4) the facilitation of payments to and by purveyors

of all of the aforementioned content through Googles payment services. Id. at p.

1.

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 5 of 22

In February 2014, Attorneys General from Nebraska, Hawaii, Utah,

Arkansas and General Hood again wrote to Googles Senior Vice President and

General Counsel. [Doc. No. 17-22]. The letter noted that [t]hough we believe, as

you do, the Denver meeting was a valuable first step in establishing a constructive

dialogue on the serious issues before us, much work remains to be done. Id. at 1.

The letter from the five (5) Attorneys General posed a series of questions for

Googles consideration which included many of the same topics that had been under

discussion through 2013 such as the monetization of dangerous and/or illegal

content through advertising sales and direct revenue sharing agreements with

producers of content which violates Googles own polices. Id. at 2.

Finally, and even continuing after Google sued the Attorney General to stop

an on-going investigation, twelve (12) state Attorneys General filed an amicus

curiae brief supporting the Attorney Generals motion to dismiss in this Court.2

[Doc. No. 77]. As noted in the brief of the amici Attorneys General:

As the chief law enforcement officers for their states charged with

protecting the vital public interest, state Attorneys General are given

broad authority to investigate activity that may violate state consumer

protection laws. The amici have a heightened interest in the Courts

resolution of this case, and particularly the Courts resolution of

General Hoods pending motion to dismiss, in light of the precedential

effect of any decision interpreting the Attorney Generals authority to

investigate potentially unlawful conduct on the Internet.

[Doc. No. 77] at p. 2.

States supporting the amicus brief included: Kentucky, Arizona, Connecticut, Illinois,

Iowa, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington.

2

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 6 of 22

Thus, this Attorney Generals issuance of the disputed Subpoena in October

2014 clearly did not occur in isolation but as demonstrated from the record, evolved

over a considerable period of time and involved the joint efforts by multiple state

Attorneys General. And as part of this process described above, the Attorney

General enlisted the assistance of various individuals and/or firms with knowledge

and expertise concerning the issues at hand as well as those who were victims of

potential violations of Mississippis consumer protection laws.3 Thus, Googles

instant motion does not present a garden-variety discovery dispute as would be the

case involving private litigants and must instead be viewed in the context in which

it occurred.

B.

Procedural History of the Attorney Generals April 15, 2015

Production of Documents and Privilege Log.

In accordance with the Courts April 10, 2015 Order (Order), the Attorney

General produced documents identified in the Order or provided a Privilege Log for

documents withheld under privilege. [Doc. 100-1]. The Attorney General asserted

The Attorney General has publically addressed Googles attempt to mischaracterize the fact

that he has worked with various industry groups during this investigation:

3

Well, yes, we worked with them [motion picture industry], we

worked with a lot of industries.

When we get a counterfeit drug, we call the drug company that

manufactures it and they do the testing on it. We do training with all

the clothing apparel. We dont know out investigators dont

necessarily know when something is counterfeit, so we have to work

with the victims. Theyre property has been stolen.

[Doc. No. 52-1] p.13.

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 7 of 22

privilege as to certain of the requested documents on the basis of: (1) the attorneyclient privilege, (2) attorney work-product; and (3) the common-interest doctrine.4

II.

Content of the Supplemental Privilege Log

Google generally argues throughout its motion that the Attorney Generals

Privilege Log and Supplemental Privilege Log do not meet the technical

requirements of L. U. Civ. R. 26(a)(1)(C). The Attorney General disagrees. After

consultation between counsel for the parties and prior to Google filing its motion to

compel, the Attorney General served on Googles counsel the First Supplemental

Privilege Log (Supplemental Privilege Log) [Doc. No. 100-1].

The Supplemental Privilege Log provides the following information: (1)

Privilege Log (PL) bates numbers of the document withheld (which identifies the

length of the withheld document), (2) a description of the document(s) withheld, (3)

the date(s) that the Attorney General received the document(s), (4) the author(s) of

the document(s), (5) the identity of the individual(s) who provided the document(s)

to the Attorney General, (6) the recipient of the document(s) at the Attorney

Generals Office, and (7) the privilege(s) asserted over the document(s). [Doc. No.

100-1].

Despite Googles characterization to the contrary, the Attorney Generals

First Supplemental Privilege Log provides more than sufficient information to allow

The common interest doctrine is not a privilege in itself, but is an exception to the waiver of

an existing privilege. The doctrine protects the transmission of data to which the attorney-client

privilege or work product protection has attached when it is shared between parties with a common

interest in a legal matter. Tobaccoville USA v. McMaster, 387 S.C. 287 (2010) (Common interest

doctrine recognized between state attorneys general).

4

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 8 of 22

Google to test the merits of a privilege claim. United Investors Life Ins. Co. v.

Nationwide Life Ins. Co., 233 F.R.D. 483, 486 (N.D. Miss. 2006). Furthermore, any

claim by Google that it did not have sufficient information from the Supplemental

Privilege Log to challenge the applicability of the asserted privilege is belied by the

specificity of the documents Google requested. Googles first document requested

sought the following:

a.

Any draft subpoenas provided to the Attorney General by

the third-parties5 identified in Googles request of

[January 14, 2015].

b.

Attorney General Hoods November 13, 2013 email to

[MPAA lobbyist] Vans Stevenson, and any replies or

responses thereto;

c.

Attorney General Hoods August 28, 2014 letter to the

Attorneys General in all 50 states regarding setting up a

working group;

d.

The Word files listed in item (6) of Googles January 14,

2015 request (Google can take action Google must

change its behavior Googles illegal conduct (CDA),

and any emails from the third parties attaching those

word files;

e.

Any documents already gathered in connection with the

Techdirt Mississippi Public Records Act request that are

responsive to Googles requests.

and

These third-parties as defined by Google are: the Motion Pictures Association of America,

Steven Fabrizio, Vans Stevenson, Kate Bedingfield, the Recording Industry Association of America,

Digital Citizens Alliance, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, Thomas

Galvin, FairSearch.org, Microsoft Corporation, Patrick Lynch Group, Lynch and Pine Attorneys at

Law, Orrick Herrington & Sufcliffe, LLP, Jenner & Block, LLP, Thomas J. Perrelli, Elizabeth

Bullock, the Mike Moore Law Firm, former Mississippi Attorney General Michael Moore, 21st

Century Fox Corp., Comcast Corporation, Viacom Inc., Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., The Walt

Disney Company, Sony Pictures Entertainment Inc., NBCUniversal.

5

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 9 of 22

[Doc. No. 100], p. 1. Based on the specific requests submitted by Google, the

information provided by the Attorney General on the Supplemental Privilege Log

was more than sufficient to allow Google to test the applicability of the asserted

privilege, which it has done in its motion.6

III.

Draft Subpoenas

A.

The Attorney-Client Privilege

As accurately reflected on the Supplemental Privilege Log, the Attorney

General received three (3) of the draft subpoenas from Mike Moore, one of the

attorneys retained by the Attorney General in 2012 regarding Google. See [Doc. No.

100-1 PL000001-PL000067; PL000075-000119, and PL000167-000176].7 With

regard to the attorney-client privilege, the Fifth Circuit has said:

Should the Court determine that the Supplemental Privilege Log does not contain sufficient

information to allow the Court and/or Google to test the merits of the asserted privilege, the

appropriate remedy is the production of a supplemental Privilege Log. See, e.g., Employers Mut. Cas.

Co. v. Maison Heidelberg, P.A., 2011 WL 1496253, *3 (S.D. Miss., April 20, 2011).

6

Google also suggests that because the draft subpoena dated April 3, 2012 predates the

signed Retention Agreement with Mike Moore it could not possibly be covered by the attorney-client

privilege. First, as is common in the attorney-client relationship, Mike Moores role as an attorney

for the Attorney General commenced prior to the date of the Retention Agreement signed on June 29,

2012. Mike Moore was acting as an attorney for the Attorney General as early as March

2012. Because Google did not request communication regarding the production of draft subpoenas,

but only the draft subpoenas themselves, the Attorney General did not identify any correspondence

with Mike Moore predating the June 29, 2012 Retention Agreement. However, the Attorney General

will supplement the Privilege Log to identify this correspondence and requests that the Court

conduct an in camera review to evaluate the applicability of the asserted attorney-client

privilege. The Supplemental Privilege Log also identifies Jeff Modisett with the law firm of SNR

Denton US LLP, as the author of the draft Subpoena dated April 3, 2012. See [Doc. 100-1] at

p.2. Mr. Modisett had an attorney-client relationship with the Attorney General which began in

January 2012. Because Mr. Modisett was not an identified third-party pursuant to Googles

document request, the draft Subpoena dated April 3, 2012 was identified only because Google had

originally identified Mike Moore as a third-party thus making it potentially responsive to the

request. The Attorney General has obviously clarified for Google that Mike Moore is not a thirdparty for purposes of the requests, but one of the Attorney Generals attorneys. The April 3, 2012

draft Subpoena was used by the Attorney General as a starting point in preparing the very limited

Subpoena which was served on Google on April 19, 2012. Google did not object to this Subpoena and

produced documents in response thereto.

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 10 of 22

The oldest of the privileges for confidential communications, the

attorney-client privilege protects communications made in confidence

by a client to his lawyer for the purpose of obtaining legal advice. The

privilege also protects communications from the lawyer to his client, at

least if they would tend to disclose the client's confidential

communications. Its application is a question of fact, to be determined

in the light of the purpose of the privilege and guided by judicial

precedents.

Hodges, Grant & Kaufmann v. U.S. of the Treasury, 768 F.2d 719, 720-21 (5th Cir.

1985) (emphasis supplied). Thus, with respect to the transmission of the draft

subpoenas from Mike Moore to the Attorney General as set forth on the

Supplemental Privilege Log, the attorney-client privilege was asserted to avoid any

subsequent claim by Google that any confidential communications between the

Attorney General and Mike Moore had been waived with respect to these draft

subpoenas. Because these draft Subpoenas were provided by Mike Moore,

representing the Attorney General, any confidential communications regarding

these subpoenas would be subject to the attorney-client privilege. Although Google

did not request communications with regard to the draft subpoenas, failure to

assert the attorney- client privilege regarding the draft subpoenas themselves could

be construed as a waiver of any confidential communications related thereto.8

Google also attacks the confidential nature of the attorney-client relationship

between the Attorney General and Mike Moore, citing as support a New York Times

newspaper article. [Doc. No. 100] p. 7. Regardless of how Google wishes to

Google takes issue with the fact that the Attorney General redacted the scope of the

Retention Agreement with the Mike Moore Law Firm. [Doc. No. 100], p. 6. n.2. The Attorney General

did produce the Retention letter to Google, with the scope of the representation redacted. [Doc. No.

100-1], p. 2. The Attorney General request that the Court conduct an in camera review of the

retention letter prior to ruling with respect to the attorney-client privilege.

8

10

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 11 of 22

characterize Mike Moores role as an attorney for the Attorney General or the

nature of his privilege communications with the Attorney General, the attorneyclient privilege belongs to the client, in this case the Attorney General and an

attorney cannot unilaterally waive the privilege. See United States v. Juarez, 573

F.2d 267, 276 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 439 U.S. 915, 99 S.Ct. 289, 58 L.Ed.2d 262

(1978). At no time has the Attorney General waived the attorney-client privilege

regarding confidential communications with Mike Moore and/or the Mike Moore

Law firm regarding his representation of the Attorney General in regard to Google.

B.

Work Product

Google next argues that the Attorney Generals claim of work-product as to

the draft subpoenas is not well-founded because certain documents for which

privilege is claimed were not originally drafted by the Attorney General or anyone

representing him. [Doc. No. 100], p. 10. As noted previously, the Attorney General

enlisted the assistance of individuals outside of his office to assist with issues

related to possible future litigation against Google.

It is well-settled that the work-product doctrine promotes the adversary

system by protecting the confidentiality of papers prepared by or on behalf of

attorneys in anticipation of litigation. Westinghouse Elec. Corp. v. Republic of

Philippines, 951 F.2d 1414 (3rd Cir. 1991). Protecting attorneys' work product

promotes the adversary system by enabling attorneys to prepare cases without fear

that their work product will be used against their clients. Hickman v. Taylor, 329

11

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 12 of 22

U.S. 495, 51011, 67 S.Ct. 385, 39394, 91 L.Ed. 451 (1947); United States v. AT &

T, 642 F.2d 1285, 1299 (D.C. Cir.1980).

Rule 26(b)(3) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides that a party

may not discover documents and tangible things that are prepared in anticipation of

litigation or for trial by or for another party or its representative (including the

other partys attorney, consultant, surety, indemnitor, insurer, or agent). The

documents withheld by the Attorney General pursuant to Rule 26(b)(3) were

prepared for the Attorney General. Furthermore, the work-product doctrine

provides qualified protection of documents and tangible things prepared in

anticipation of litigation, including a lawyer's research, analysis of legal theories,

mental impressions, notes, and memoranda of witnesses' statements. Dunn v.

State Farm Fire & Cas. Co., 927 F.2d 869, 875 (5th Cir. 1991) (citing Upjohn Co. v.

United States, 449 U.S. 383, 400, 101 S.Ct. 677, 66 L.Ed.2d 584 (1981); United

States v. El Paso Co., 682 F.2d 530, 543 (5th Cir. 1982)). Ferko v. Nat. Assn for

Stock Car Auto Racing, 219 F.R.D. 396 (E.D. Tex. 2003).

The work product protection is broader in scope and reach than the attorneyclient privilege because it extends only to client communications, while the work

product protection encompasses much that outside of client communications. See

United States v. Nobles, 422 U.S. 225, 238, 95 S.Ct. 2160, 45 L.Ed.2d 141 (1975).

Further, Rule 26(b)(3) permits disclosure of documents and tangible things

constituting attorney work product only upon a showing of substantial need and

12

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 13 of 22

inability to obtain the equivalent without undue hardship. Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(3).

Google cannot make a showing of substantial need.

The work product privilege applies to documents prepared in anticipation of

litigation. Fed. R. Civ. P. 26(b)(3). The law in this Circuit is that the work product

privilege can apply even where litigation is not imminent as long as the primary

motivating purpose behind the creation of the document was to aid in possible

future litigation.9 In re Kaiser Aluminum and Chem. Co., 214 F.3d 586 (5th Cir.

2000). To establish work product protection, a party must show the primary

motivating purpose behind the creation of a document was to aid in possible future

litigation . . . whether a document is protected depends on the motivation behind its

preparation, rather than on the person who prepares it. Grochocinski v. Mayer

Brown Rowe & Maw LLP, 251 F.R.D. 316, 321 (N.D. Ill. 2008) (emphasis supplied);

see also Boyer v. Gildea, 257 F.R.D. 488 (N.D. IN 2009) ([W]hether a document is

protected depends on the motivation behind its preparation, rather than on the

person who prepares it.). Id.

Google seeks to undermine the very nature of the adversary system fostered

by the work-product privilege by demanding the production of draft subpoenas

prepared for the Attorney General in anticipation of litigation. Allowing Google

access to these draft subpoenas would obviously allow it to review earlier drafts of

Google does not strenuously contest the fact that the material was prepared in anticipation

of litigation, nor could it given the legal arguments advanced in this case. For instance, Google

contends that as early as April 2013, it began making changes to its editorial judgments about what

Autocomplete predictions would block due to alleged threats. See [Doc. No. 54-2]. While the

Attorney General vigorously disputes the factual assertions of Googles position, by its own

admission, it allegedly deemed possible litigation as a possibility.

9

13

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 14 of 22

the subpoena then compare the drafts against the Subpoena actually served by the

Attorney General on October 14, 2014. This is simply a back-door tactic by Google

to gain access to the Attorney Generals work product leading up to the issuance of

the Subpoena.

Disclosure of work product results in waiver of work-product protection only

if work-product is disclosed to adversaries or treated in a manner that substantially

increases the likelihood that an adversary will come into possession of the material.

Ferko v. National Ass'n for Stock Car Auto Racing, Inc., 218 F.R.D. 125 (E.D. Tx.

2003). Here, the draft subpoenas were not disclosed to Google or treated in a

manner that substantially increased the likelihood that Google would come into

possession of the material. This is evidenced by the fact that Google now seeks the

draft subpoenas.

With respect to whether the primary motivating purpose behind the

Subpoena was to aid in possible future litigation, the answer to this question is

clearly in the affirmative. Once this matter reached the stage of preparing the

Subpoena, litigation was obviously a possibility. First, had Google not filed this

instant lawsuit and failed to comply with the Subpoena, the Attorney General

would have been required to file an enforcement action in state court pursuant to

Miss. Code Ann. 75-24-17 to compel the production of the documents sought in the

Subpoena. Thus, litigation of the enforcement of the Subpoena was certainly likely.

Second, had the Attorney Generals Subpoena provided information or documents

evidencing violations of Mississippis Consumer Protection Act, then information

14

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 15 of 22

obtained through the Subpoena would certainly have been used to aid in future

litigation for any putative claims against Google arising under the Mississippi

Consumer Protection Act.

In this case, draft subpoenas were prepared and sent to either the Attorney

General directly, or to Mike Moore, the Attorney Generals outside attorney for use

by the Attorney General as he saw fit. Those draft subpoenas were then used by

the Attorney General and his staff to prepare the final Subpoena served on Google

on October 14, 2014. To allow Google the benefit of this work and the progression of

the drafts leading up to the final Subpoena is simply to allow it the fruits of the

Attorney Generals work product without having made the requisite showing. Such

discovery in this particular case certainly undermines the very nature of the work

product doctrine, in that [p]rotecting [an] attorneys' work product promotes the

adversary system by enabling attorneys to prepare cases without fear that their

work product will be used against their clients. Hickman, 329 U.S. at 51011.

The Supplemental Privilege Log shows that drafts Subpoenas were drafted

by Tom Perrelli and/or Brian Moran. While neither Mr. Moran nor Mr. Perrelli

represented the Attorney General, both provided assistance to General Hood and

prepared draft subpoenas for the benefit of and for Attorney Generals use. These

draft subpoenas were then used by the Attorney General and his staff. Allowing

Google access to draft subpoenas would provide it with information concerning the

evolution of the Subpoena, the thought processes of the attorneys in General Hoods

15

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 16 of 22

office as well as mental impressions of his staff who prepared the subpoenas.10 This

is precisely the type of information the work-product privilege is designed to protect.

The only possible reason Google wants draft subpoenas is merely to gain further

insight into the Attorney Generals investigation. The Attorney General urges the

Court to reject such an expedition.

IV.

The Word Files Constitute Work Product.

The so-called Word Files sought by Google in the first request for

production were provided by Tom Perrelli in response to questions posed to Mr.

Perrelli by the Attorney General. Allowing Google access to these documents and

communications would reveal the nature of the Attorney Generals mental

impressions and strategy regarding future litigation against Google. The Attorney

General requests that the Court conduct an in camera review of the documents and

Google has also issued subpoenas to produce documents to Jenner and Block, LLP , where

Mr. Perrelli is employed. See [Doc. No. 85-1]. Even as a third-party, Mr. Perrelli is entitled to assert

his own work product with respect to documents he prepared for the Attorney General. As the Court

in In re: Student Finance Corp. stated:

10

Rule 26(b)(3), however, is not the only means for asserting work product protection in

federal courts. The rule is only a partial codification of the work product privilege, [ ]

and therefore leaves room for the privilege to be asserted outside its terms in

appropriate cases. Courts have extended the work product privilege beyond the strict

terms of Rule 26(b)(3) to protect intangible work product outside the documents and

tangible things protected by the rule. [ ]. Similarly, the Court believes the privilege

may be extended beyond the strict terms of the rule to protect non-parties' work

product when doing so accords with the purposes of the privilege set out in Hickman v.

Taylor.

2006 WL 3484387, at *10 (E.D. Penn. Nov. 29, 2006) (internal citations and quotations

omitted).

16

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 17 of 22

communication between Mr. Perrelli and the Attorney Generals staff which will

substantiate the applicability of the work-product privilege.11

Furthermore, the same considerations set forth in footnote 7, supra, apply

with equal force to the work-product of Mr. Perrelli. The Attorney General should

not be required to produce to Google the content of a protected communication for

the purpose of substantiating the privilege. The United States Supreme Court has

long held the view that in camera review is a highly appropriate and useful means

of dealing with claims of governmental privilege. See, e.g., United States v. Nixon,

418 U.S. 683, 706, 94 S.Ct. 3090, 3106, 41 L.Ed.2d 1039 (1974) (emphasis supplied);

United States v. Reynolds, 345 U.S. 1, 73 S.Ct. 528, 97 L.Ed. 727 (1953). Thus, the

Attorney General requests that the Court conduct an in camera review of the Word

Files and related correspondence to determine the existence of the work-product

privilege.

V.

The Redacted Letters Authored by the Attorney General and Sent to

other State Attorneys General Constitutes Work-Product.

Google argues in its motion that the Attorney General must produce letters

he sent to other state Attorneys General without redaction. [Doc. No. 100], p. 13.

The Attorney General produced a portion of the letters in question owing to the fact

that the material did not constitute work product. The redacted material in the

letters, however, do contain the Attorney Generals own work product including

research, strategy and mental impressions regarding potential claims against

The applicable documents with respect to the work-product privilege to the Word Files

are set forth in the Supplemental Privilege Log and bates numbered PL000223-000245.

11

17

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 18 of 22

Google. The Attorney General requests that the Court conduct an in camera review

of the redacted letter so as to assess the assertion of the work-product privilege.

Again, Google cannot demonstrate a substantial need for the redacted

content of the letter other than its desire to gain as much insight as possible into

the nature of the Attorney Generals communications with his counter-parts in

other states. Allowing this intrusion into this type of work-product does injury to

the public interest by allowing an individual and/or entity to gain access into

potential multi-state litigation. In camera review of the letter will demonstrate that

the redacted portion of the letter contains the Attorney Generals See, e.g., United

States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683, 706, 94 S.Ct. 3090, 3106, 41 L.Ed.2d 1039 (1974);

United States v. Reynolds, 345 U.S. 1, 73 S.Ct. 528, 97 L.Ed. 727 (1953).

Google takes exception to the Attorney Generals assertion of the commoninterest doctrine regarding the letter to other Attorneys General. While the

common interest doctrine is not privilege in and of itself, it is an extension of the

attorney-client privilege and of the work-product doctrine. See In re LTV Secs.

Litig., 89 F.R.D. 595, 604 (N.D. Tex. 1981) (noting that the common interest

doctrine extends the attorney-client privilege to communications made in the

course of joint defense activities); see also Power Mosfet Techs. v. Siemens AG, 206

F.R.D. 422, 424 (E.D. Tex. 2000) (stating that the common interest doctrine applies

to the work-product doctrine). Generally, when an attorney divulges privileged

information to a third party, attorney-client and work-product protection cease to

exist. See United States v. Pipkins, 528 F.2d 559, 563 (5th Cir.1976).

18

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 19 of 22

The common interest doctrine, however, extends a recognized privilege,

commonly the attorney-client or work product privileges, to cover those

communications. Siemens AG, 206 F.R.D. at 424. Consequently, the common

interest doctrine is an exception to the general rule that the attorney-client

privilege is waived upon disclosure of privileged information with a third party.

Katz v. AT & T Corp., 191 F.R.D. 433, 436 (E.D. Pa. 2000) (citations omitted). This

exception also applies to the work-product doctrine. Siemens AG, 206 F.R.D. at 424.

The common interest doctrine protects communications between two parties or

attorneys that share a common legal interest.

Google cites In re: Santa Fe Corp., 272 F.3d 705, 710 (5th Cir. 2001) arguing

that the common interest doctrine only applies for (1) communications between codefendants in actual litigation and their counsel; and (2) communications between

potential co-defendants and their counsel. Id. at 710. While the Fifth Circuit has

not addressed the precise issue before this Court, i.e., the applicability of the

common-interest doctrine between state Attorneys General, at least two other

Courts have recognized the doctrine regarding the sharing of information between

Attorneys General and the National Association of Attorneys General. See

Tobaccoville USA, Inc., v. McMaster, 387 S.C. 287 (2010) and Grand River

Enterprise Six Nations, Ltd. v. Pryor, 2008 WL 1826490, at *3 (Apr. 18, 2008

S.D.N.Y). Because this is not the ordinary dispute between private litigants, but

involves an investigation by the chief law enforcement officer of the State of

Mississippi, sharing confidential information with other Attorneys General for

19

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 20 of 22

purposes of possible multi-state litigation must be viewed differently. Therefore, the

letters sent by General Hood to other state Attorneys General should be protected

as work product.

VI.

Conclusion

For the reasons set forth, the Attorney General respectfully requests that the

Court deny Googles motion to compel. In the alternative, the Attorney General

requests that the Court conduct an in camera review of the documents for purposes

of testing the privilege asserted prior to ruling on the motion.

THIS the 29th day of April, 2015.

Respectfully Submitted,

JIM HOOD, in his official capacity as

Attorney General of the State of

Mississippi

By:

JIM HOOD, ATTORNY GENERAL,

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

By:

/s/ Douglas T. Miracle

DOUGLAS T. MIRACLE (Bar No. 9648)

SPECIAL ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

20

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 21 of 22

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

BRIDGETTE W. WIGGINS (MSB # 9676)

SPECIAL ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

KRISSY CASEY NOBILE (MSB # 103577)

SPECIAL ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

Post Office Box 220

Jackson, MS 39205

Telephone No. (601)359-5654

bwill@ago.state.ms.us

knobi@ago.state.ms.us

dmira@ago.state.ms.us

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, Douglas T. Miracle, Special Assistant Attorney General for the State

of Mississippi, hereby certify that a true and correct copy of the foregoing

document has been served via electronic mail and United States Mail on the

following:

Fred Krutz , III

Daniel J. Mulholland

FORMAN, PERRY, WATKINS, KRUTZ & TARDY, LLP

P.O. Box 22608

200 S. Lamar Street, Suite 100 (39201-4099)

Jackson, MS 39225-2608

Email: mulhollanddj@fpwk.com

Email: fred@fpwk.com

David H. Kramer - PHV

WILSON, SONSINI, GOODRICH & ROSATI, PC

650 Page Mill Road

Palo Alto, CA 94304-1050

Email: dkramer@wsgr.com

21

Case 3:14-cv-00981-HTW-LRA Document 103 Filed 04/29/15 Page 22 of 22

Blake C. Roberts - PHV

WILMER, CUTLER, PICKERING, HALE & DORR, LLP

1801 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20006

Email: blake.roberts@wilmerhale.com

Jamie S. Gorelick - PHV

WILMER, CUTLER, PICKERING, HALE & DORR, LLP

1801 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20006

Email: jamie.gorelock@wilmerhale.com

Patrick J. Carome - PHV

WILMER, CUTLER, PICKERING, HALE AND DORR, LLP

1875 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20006

Email: patrick.carome@wilmerhale.com

Peter Neiman - PHV

WILMER, CUTLER, PICKERING, HALE AND DORR, LLP

7 World Trade Center

250 Greenwich Street

New York, NY 10007

Email: peter.neiman@wilmerhale.com

Violetta G. Watson - PHV

WILMER, CUTLER, PICKERING, HALE AND DORR, LLP

7 World Trade Center

250 Greenwich Street

New York, NY 10007

Email: violetta.watson@wilmerhale.com

THIS the 29th day of April, 2015.

/s/ Douglas T. Miracle

DOUGLAS T. MIRACLE

22

También podría gustarte

- Missouri-Louisiana Fact Finding Documents Filed in Lawsuit Against Biden AdministrationDocumento364 páginasMissouri-Louisiana Fact Finding Documents Filed in Lawsuit Against Biden AdministrationJim HoftAún no hay calificaciones

- Demolition Agenda: How Trump Tried to Dismantle American Government, and What Biden Needs to Do to Save ItDe EverandDemolition Agenda: How Trump Tried to Dismantle American Government, and What Biden Needs to Do to Save ItAún no hay calificaciones

- Abuse of Process - The Basics and Practicalities - Stimmel Law PDFDocumento5 páginasAbuse of Process - The Basics and Practicalities - Stimmel Law PDFNazar Lawyer100% (1)

- PEER Report On MDOC Electronic MonitoringDocumento54 páginasPEER Report On MDOC Electronic MonitoringRuss Latino100% (1)

- DHS AuditDocumento100 páginasDHS Auditthe kingfish100% (1)

- 192 Drafted Amended First Complaint WMDocumento94 páginas192 Drafted Amended First Complaint WMthe kingfishAún no hay calificaciones

- Curling Vs RaffenspergerDocumento135 páginasCurling Vs RaffenspergerRobert GouveiaAún no hay calificaciones

- The California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) – An implementation and compliance guideDe EverandThe California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) – An implementation and compliance guideAún no hay calificaciones

- Holmberg v. HolmbergDocumento8 páginasHolmberg v. HolmbergCorey JacksonAún no hay calificaciones

- The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA): An implementation guideDe EverandThe California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA): An implementation guideCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (2)

- GEICO General Insurance Company v. Michael J. Kastenolz, 11th Cir. (2016)Documento9 páginasGEICO General Insurance Company v. Michael J. Kastenolz, 11th Cir. (2016)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- PEER On PERSDocumento44 páginasPEER On PERSRuss LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- How to Remain Anonymous Online: A Users Guide UpdatedDe EverandHow to Remain Anonymous Online: A Users Guide UpdatedAún no hay calificaciones

- Bryant MT ComplaintDocumento27 páginasBryant MT Complaintthe kingfishAún no hay calificaciones

- SPGJ - Brief of Media IntervenorsDocumento109 páginasSPGJ - Brief of Media IntervenorsWSB-TV Assignment DeskAún no hay calificaciones

- Teacher Prep Review - Strengthening Elementary Reading InstructionDocumento105 páginasTeacher Prep Review - Strengthening Elementary Reading InstructionRuss LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- OSA City of Jackson Analysis PDFDocumento7 páginasOSA City of Jackson Analysis PDFthe kingfishAún no hay calificaciones

- Wingate Status Conference Response - Jackson WaterDocumento7 páginasWingate Status Conference Response - Jackson WaterRuss LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- The Cost of "Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion" Programs at Mississippi Public UniversitiesDocumento322 páginasThe Cost of "Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion" Programs at Mississippi Public UniversitiesRuss Latino0% (1)

- Upcoming Updates In Data Protection: Whistleblowing ChannelsDe EverandUpcoming Updates In Data Protection: Whistleblowing ChannelsAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Comment On Google v. EquustekDocumento7 páginasCase Comment On Google v. EquustekRajwant Singh BamelAún no hay calificaciones

- Section 230: Free Speech and the Internet, the Law That Makes It All PossibleDe EverandSection 230: Free Speech and the Internet, the Law That Makes It All PossibleAún no hay calificaciones

- Cesar Sampayan vs. Crispulo Vasquez and Florencia Vasquez-Galisano (GR No. 156360, 14 Jan 2005)Documento3 páginasCesar Sampayan vs. Crispulo Vasquez and Florencia Vasquez-Galisano (GR No. 156360, 14 Jan 2005)Archibald Jose Tiago ManansalaAún no hay calificaciones

- AG Jim Hood Exhibits 021116Documento8 páginasAG Jim Hood Exhibits 021116Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Notice To Depose MS AG Jim Hood 021916Documento8 páginasNotice To Depose MS AG Jim Hood 021916Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Flores V UberDocumento7 páginasFlores V UberLegal WriterAún no hay calificaciones

- Tort LawDocumento11 páginasTort LawmageroojiamboAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Comment: "The GDPR"Documento5 páginasCase Comment: "The GDPR"Aksh JainAún no hay calificaciones

- Google Privacy Policy RulingDocumento30 páginasGoogle Privacy Policy Rulingjeff_roberts881Aún no hay calificaciones

- BR 2500 LRTPDocumento13 páginasBR 2500 LRTPmageroojiamboAún no hay calificaciones

- Dotcom Evidence 2Documento9 páginasDotcom Evidence 2Eriq GardnerAún no hay calificaciones

- Big Data Seizing Opportunities Preserving Values MemoDocumento11 páginasBig Data Seizing Opportunities Preserving Values MemoRon Miller100% (1)

- Google Antitrust LawsuitDocumento64 páginasGoogle Antitrust LawsuitErin FuchsAún no hay calificaciones

- Gerald Young v. GrowLife, Inc. Et Al Doc 1 Filed 25 Apr 14Documento34 páginasGerald Young v. GrowLife, Inc. Et Al Doc 1 Filed 25 Apr 14scion.scionAún no hay calificaciones

- Memo in Support of Protective Order by MS AG Jim Hood 021116Documento9 páginasMemo in Support of Protective Order by MS AG Jim Hood 021116Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Teva Whistleblower (SEC Response)Documento38 páginasTeva Whistleblower (SEC Response)Mike KoehlerAún no hay calificaciones

- Gov - Uscourts.vtd.29948.1.0 1Documento31 páginasGov - Uscourts.vtd.29948.1.0 1Spit FireAún no hay calificaciones

- 5 23 CV 05824 Google V Nguyen Van Duc Pham Van Thien Complaint 231113Documento16 páginas5 23 CV 05824 Google V Nguyen Van Duc Pham Van Thien Complaint 231113aquasetup1Aún no hay calificaciones

- See Address by Seth P. Waxman, Solic. Gen. of The U.S., To The Sup. Ct. Hist. Soc'y, "Presenting The Case of TheDocumento5 páginasSee Address by Seth P. Waxman, Solic. Gen. of The U.S., To The Sup. Ct. Hist. Soc'y, "Presenting The Case of TheProtocolAún no hay calificaciones

- Montgomery V Risen # 177 - D Resp To K Objection & Req To StayDocumento79 páginasMontgomery V Risen # 177 - D Resp To K Objection & Req To StayJack RyanAún no hay calificaciones

- In Re Chiquita Brands: Opposition To Motion For Reconsideration Based On Twitter V TaamnehDocumento9 páginasIn Re Chiquita Brands: Opposition To Motion For Reconsideration Based On Twitter V TaamnehPaulWolfAún no hay calificaciones

- Globalisation's Impact On Judicial ProcessDocumento3 páginasGlobalisation's Impact On Judicial ProcessKarishma Tamta0% (1)

- 2020-07-14 (Dkt. 1) Rodgriguez Et Al. V Google LLC Et Al.Documento42 páginas2020-07-14 (Dkt. 1) Rodgriguez Et Al. V Google LLC Et Al.jonathan_skillings100% (1)

- 13-07-11 Google Motion To Intervene in ITC Investigation of Nokia's Second Complaint Against HTCDocumento12 páginas13-07-11 Google Motion To Intervene in ITC Investigation of Nokia's Second Complaint Against HTCFlorian MuellerAún no hay calificaciones

- Clear Answers and Standards On Data Privacy Protection."Documento2 páginasClear Answers and Standards On Data Privacy Protection."Anonymous ZXXhPuYZXAún no hay calificaciones

- Brown V Google ComplaintDocumento22 páginasBrown V Google ComplaintEric GoldmanAún no hay calificaciones

- Montgomery V Risen # 187 - D Opp To Motion To Extend Discovery DeadlineDocumento94 páginasMontgomery V Risen # 187 - D Opp To Motion To Extend Discovery DeadlineJack RyanAún no hay calificaciones

- Issue Guide Final DraftDocumento12 páginasIssue Guide Final Draftapi-665635659Aún no hay calificaciones

- Montgomery V Risen # 94 - S.D.Fla. - 1-15-cv-20782 - 94 - D Memo of Law Re 91Documento139 páginasMontgomery V Risen # 94 - S.D.Fla. - 1-15-cv-20782 - 94 - D Memo of Law Re 91Jack RyanAún no hay calificaciones

- Gawker Financial Worth Arguments & ExhibitsDocumento133 páginasGawker Financial Worth Arguments & ExhibitsdavidbixAún no hay calificaciones

- Answers To Parts Ii, Iii and Iv: INSTRUCTOR: Judy Koch Mid-Term ExamDocumento6 páginasAnswers To Parts Ii, Iii and Iv: INSTRUCTOR: Judy Koch Mid-Term Examluckytung07Aún no hay calificaciones

- EMI Opposition To GoogleDocumento9 páginasEMI Opposition To Googleconcerned-citizen100% (1)

- United States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitDocumento45 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitScribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- O'Kroley v. Fastcase, Google - 6th Circuit PDFDocumento5 páginasO'Kroley v. Fastcase, Google - 6th Circuit PDFMark JaffeAún no hay calificaciones

- 21-1333 6j7aDocumento3 páginas21-1333 6j7aABC News PoliticsAún no hay calificaciones

- USSupremeCourtdecisiononreversepaymentagreements-Actavic QMIPJ 2012Documento11 páginasUSSupremeCourtdecisiononreversepaymentagreements-Actavic QMIPJ 2012momenajibAún no hay calificaciones

- 4 WrighttoMe CtechHines 7-14-14gmail Complaint No. 20373Documento3 páginas4 WrighttoMe CtechHines 7-14-14gmail Complaint No. 20373Lisbon ReporterAún no hay calificaciones

- Committee For Justice Comments To The FTC On Competition and Consumer Protection in The 21st CenturyDocumento12 páginasCommittee For Justice Comments To The FTC On Competition and Consumer Protection in The 21st CenturyThe Committee for JusticeAún no hay calificaciones

- Motion To Default Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP For Indirect Criminal ContemptDocumento146 páginasMotion To Default Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP For Indirect Criminal ContemptChristopher Stoller EDAún no hay calificaciones

- Legal Environment of Business Text and Cases 9th Edition Cross Solutions ManualDocumento13 páginasLegal Environment of Business Text and Cases 9th Edition Cross Solutions Manualgalvinegany3a72j100% (27)

- Complaint FGI v. DHS 22-Cv-02737Documento11 páginasComplaint FGI v. DHS 22-Cv-02737Gabe KaminskyAún no hay calificaciones

- Google Trademark DecisionDocumento23 páginasGoogle Trademark DecisionMMA PayoutAún no hay calificaciones

- GDG Acquisitions, LLC v. Government of Belize, 11th Cir. (2014)Documento22 páginasGDG Acquisitions, LLC v. Government of Belize, 11th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- 10-23-17 Analysis of CFPB Arbitration RuleDocumento18 páginas10-23-17 Analysis of CFPB Arbitration RuleHYDROGENEAún no hay calificaciones

- Chokepoints: Global Private Regulation on the InternetDe EverandChokepoints: Global Private Regulation on the InternetAún no hay calificaciones

- Tax Policy and the Economy, Volume 37De EverandTax Policy and the Economy, Volume 37Robert A. MoffittAún no hay calificaciones

- Tackling Land Corruption by Political Elites: The Need for a Multi-Disciplinary, Participatory ApproachDe EverandTackling Land Corruption by Political Elites: The Need for a Multi-Disciplinary, Participatory ApproachAún no hay calificaciones

- Manual of Mediation and Arbitration in Intellectual Property: model for developing countriesDe EverandManual of Mediation and Arbitration in Intellectual Property: model for developing countriesAún no hay calificaciones

- Federal Procurement Ethics: The Complete Legal GuideDe EverandFederal Procurement Ethics: The Complete Legal GuideAún no hay calificaciones

- FY 25 Final Action Budget Top Sheet 5.4.24Documento2 páginasFY 25 Final Action Budget Top Sheet 5.4.24Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

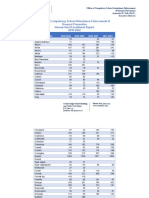

- Magnolia Tribune-Mason Dixon Governor's Poll (October 2023)Documento7 páginasMagnolia Tribune-Mason Dixon Governor's Poll (October 2023)Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- DOJ Langston-Farese-GattoDocumento33 páginasDOJ Langston-Farese-GattoNick PopeAún no hay calificaciones

- Madison Mayor Sues Three SupervisorsDocumento19 páginasMadison Mayor Sues Three SupervisorsAnthony WarrenAún no hay calificaciones

- U.S. Department of Education Response To IHL - October 31, 2023Documento4 páginasU.S. Department of Education Response To IHL - October 31, 2023Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Office of Compulsory School Attendance Enforcement & Dropout Prevention Homeschool Enrollment Report 2018-2022Documento6 páginasOffice of Compulsory School Attendance Enforcement & Dropout Prevention Homeschool Enrollment Report 2018-2022Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- NAR Lt. Governor's Poll (May 22-24, 2023)Documento12 páginasNAR Lt. Governor's Poll (May 22-24, 2023)Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Gunasekara SCOTUS Appeal May 2023Documento46 páginasGunasekara SCOTUS Appeal May 2023Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Order Dismissing Randolph - NAACP v. ReevesDocumento24 páginasOrder Dismissing Randolph - NAACP v. ReevesRuss LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Memorandum Dismissing Zack Wallace 05.11.23Documento6 páginasMemorandum Dismissing Zack Wallace 05.11.23Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Hosemann Letter To Secretary WatsonDocumento7 páginasHosemann Letter To Secretary WatsonRuss LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- H.B. 1020 AppealDocumento10 páginasH.B. 1020 AppealAnthony WarrenAún no hay calificaciones

- SCOTUS On National Guard FLRA CaseDocumento23 páginasSCOTUS On National Guard FLRA CaseRuss LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- HB 1020 Appeal 1Documento2 páginasHB 1020 Appeal 1Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Order of Dismissal As To Chief Justice Randolph 05.11.23Documento2 páginasOrder of Dismissal As To Chief Justice Randolph 05.11.23Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Order of Dismissal As To Zack Wallace 05.11.23Documento2 páginasOrder of Dismissal As To Zack Wallace 05.11.23Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- OSA 2019 Single AuditDocumento424 páginasOSA 2019 Single AuditRuss LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Intent To Sue LetterDocumento7 páginasIntent To Sue LetterRuss LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- MHA Termination Letter - May 8, 2023 - Mississippi Hospital AssociationDocumento1 páginaMHA Termination Letter - May 8, 2023 - Mississippi Hospital AssociationRuss LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Revenue Report April 2023-1Documento8 páginasRevenue Report April 2023-1Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Memorial MHA Termination 05-01-23Documento1 páginaMemorial MHA Termination 05-01-23Russ LatinoAún no hay calificaciones

- Techniques in Answering Bar QuestionsDocumento9 páginasTechniques in Answering Bar QuestionsTweenieSumayanMapandiAún no hay calificaciones

- Case 1: Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. SawyerDocumento4 páginasCase 1: Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyerapi-595424641Aún no hay calificaciones

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocumento31 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Commonwealth v. BerkowitzDocumento1 páginaCommonwealth v. Berkowitzerichesa32Aún no hay calificaciones

- Img - 10/13/2022 - Fiduciary AppointmentsDocumento28 páginasImg - 10/13/2022 - Fiduciary Appointmentsal malik ben beyAún no hay calificaciones

- Raymond A. McQuoid v. Joseph A. Smith, Sheriff, County of Worcester, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 556 F.2d 595, 1st Cir. (1977)Documento6 páginasRaymond A. McQuoid v. Joseph A. Smith, Sheriff, County of Worcester, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 556 F.2d 595, 1st Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Under Article 32, Article 136 of Constitution of Flavia Read With Rule 47 of CPCDocumento41 páginasUnder Article 32, Article 136 of Constitution of Flavia Read With Rule 47 of CPCAbhisek DashAún no hay calificaciones

- Powers of The OfficersDocumento9 páginasPowers of The Officersgamerslog124Aún no hay calificaciones

- Catherine JACKSON, On Behalf of Herself and All Others Similarly Situated, Appellant, v. Metropolitan Edison Company, A Pennsylvania CorporationDocumento13 páginasCatherine JACKSON, On Behalf of Herself and All Others Similarly Situated, Appellant, v. Metropolitan Edison Company, A Pennsylvania CorporationScribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Final Exam DR GalizaDocumento13 páginasFinal Exam DR GalizaJimbo TesoroAún no hay calificaciones

- Recent Feminist JudgmentsDocumento31 páginasRecent Feminist JudgmentsggAún no hay calificaciones

- Election Commission India V.saka Venkata SubbaDocumento8 páginasElection Commission India V.saka Venkata SubbaR Vigneshwar100% (1)

- The Philippine Bill of 1902Documento21 páginasThe Philippine Bill of 1902Lizzy WayAún no hay calificaciones

- DeSantis Mask Appeal Request For Supreme Court JurisdictionDocumento11 páginasDeSantis Mask Appeal Request For Supreme Court JurisdictionCharles R. Gallagher IIIAún no hay calificaciones

- CVCS Lesson Morda AllDocumento29 páginasCVCS Lesson Morda Alli am henryAún no hay calificaciones

- The State of Emergency and Role of Indian CourtsDocumento37 páginasThe State of Emergency and Role of Indian CourtsAvni Kumar SrivastavaAún no hay calificaciones

- Hartzel v. United States, 322 U.S. 680 (1944)Documento10 páginasHartzel v. United States, 322 U.S. 680 (1944)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Matabuena v. CervantesDocumento2 páginasMatabuena v. CervantesIzia Lopez AniscolAún no hay calificaciones

- JudiciaryDocumento21 páginasJudiciaryAdityaAún no hay calificaciones

- Respondent Moot CourtDocumento21 páginasRespondent Moot CourtHari HarikrishnanAún no hay calificaciones

- EDISON SO v. Republic of The Philippines G.R No. 170603 January 29, 2007Documento2 páginasEDISON SO v. Republic of The Philippines G.R No. 170603 January 29, 2007Khen TamdangAún no hay calificaciones

- CO Motion For Denial CompleteDocumento224 páginasCO Motion For Denial CompleteDaniel Deydanyu Nesta JohnsonAún no hay calificaciones

- Mahesh Industries PVT LTD and Ors Vs Karur Vysya BUP2019261219161047298COM78267Documento14 páginasMahesh Industries PVT LTD and Ors Vs Karur Vysya BUP2019261219161047298COM78267Keshav BahetiAún no hay calificaciones

- H. Gordon Howard v. The State Department of Highways of Colorado, 478 F.2d 581, 10th Cir. (1973)Documento6 páginasH. Gordon Howard v. The State Department of Highways of Colorado, 478 F.2d 581, 10th Cir. (1973)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Gennaro J. Angiulo, 497 F.2d 440, 1st Cir. (1974)Documento4 páginasUnited States v. Gennaro J. Angiulo, 497 F.2d 440, 1st Cir. (1974)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- David Reyes vs. Jose Lim, Et Al. (G.R. No. 134241, August 11, 2003)Documento12 páginasDavid Reyes vs. Jose Lim, Et Al. (G.R. No. 134241, August 11, 2003)Fergen Marie WeberAún no hay calificaciones

- GR 221697 Grace Poe Vs Comelec PDFDocumento254 páginasGR 221697 Grace Poe Vs Comelec PDFJP De La PeñaAún no hay calificaciones

- 254-Article Text-507-1-10-20220114Documento6 páginas254-Article Text-507-1-10-20220114M.Sufyan wainsAún no hay calificaciones