Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Lesson Learnt From Water Cube Project

Cargado por

Thomas Teh Qian HuaDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Lesson Learnt From Water Cube Project

Cargado por

Thomas Teh Qian HuaCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

This article was downloaded by: [University of Malaya]

On: 05 March 2015, At: 07:54

Publisher: Taylor & Francis

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Architectural Engineering and Design

Management

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/taem20

Lessons Learned from Managing the

Design of the Water Cube National

Swimming Centre for the Beijing 2008

Olympic Games

a

Patrick X. W. Zou & Rob Leslie-Carter

Faculty of the Built Environment , The University of New South

Wales , Sydney, Australia

b

Arup Project Management , Sydney, Australia

Published online: 06 Jun 2011.

To cite this article: Patrick X. W. Zou & Rob Leslie-Carter (2010) Lessons Learned from Managing

the Design of the Water Cube National Swimming Centre for the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games,

Architectural Engineering and Design Management, 6:3, 175-188

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3763/aedm.2010.0114

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the

Content) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,

our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to

the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions

and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,

and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content

should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,

proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or

howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising

out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/termsand-conditions

ARTICLE

Lessons Learned from Managing the

Design of the Water Cube National

Swimming Centre for the Beijing 2008

Olympic Games

Patrick X. W. Zou1, * and Rob Leslie-Carter2

1

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

Faculty of the Built Environment, The University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Arup Project Management, Sydney, Australia

Abstract

This article discusses the main lessons learned from the management of the design of the Water Cube National

Swimming Aquatic Centre (a landmark building for the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games), including forming an

international partnership, managing cultural differences and risks, dealing with intellectual property and

ownership of design to establish a legacy. The article also discusses design management strategies and

innovations. It was found that Beijings lack of regulatory transparency, regional differences and a relationshipbased business culture were some of the factors that made China a challenging project environment. Cultural

understanding and relationship (guanxi) building were fundamental strategies in responding to these

challenges. It was also found that developing a shared ownership of intellectual property and innovative design

ideas may facilitate the collaboration between Western and Chinese partners. In addition, it was necessary for

the foreign design and project management teams to be continuously involved in the construction stage to

ensure the conversion of design into reality, construction quality and personal fulfilment.

B Keywords China; design innovation; design management; guanxi; interface management; international project

INTRODUCTION AND AIM

The Beijing 2008 Olympic Games provided great

opportunities

for

international

architecture,

engineering and construction firms to demonstrate

their ability in design and project management.

Considering the new technologies, new materials

and innovative designs adopted in the Olympic

projects, coupled with the complexity of design and

construction as well as the diversified cultural

backgrounds of the project teams, there were many

challenges for the design and construction of these

projects. As such, many lessons can be learned from

the successful projects. For example, the Water

Cube National Swimming Aquatic Centre, one of the

landmark buildings for the Beijing 2008 Olympic

Games, provided a number of successful project

management practices and strategies. This article

uses the Water Cube as a successful international

complex project to investigate and document the

lessons learned, which could be a useful reference

for future project and design management in

international building/construction projects.

PROJECT BRIEF AND OBJECTIVES

The functional requirements for the Water Cube

project included a 50m competition pool, a 33m

diving pool and a 50m warm-up pool. The main pool

hall was to have 17,000 seats and the whole facility

B *Corresponding author: Email: p.zou@unsw.edu.au

ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT B 2010 B VOLUME 6 B 175188

doi:10.3763/aedm.2010.0114 2010 Earthscan ISSN: 1745-2007 (print), 1752-7589 (online) www.earthscan.co.uk/journals/aedm

176 P. X. W. ZOU AND R. LESLIE-CARTER

had to accommodate everything required for an

Olympic operational overlay. Following the Games,

the main pool hall was to be reduced to 7000 seats,

with other facilities added in order to make the

Aquatic Centre a viable long-term legacy. The Beijing

Municipal Government expected to successfully build

the best Olympic swimming venue that would then

become a popular and well-used leisure and training

facility after the Games. It included several criteria:

Quality: the best Olympic swimming venue

representing the spirit of the Beijing Olympics

the green games, the high-tech games and the

peoples games.

l Cost: no more than US$100 million before the

Olympics and US$10 million for its conversion to

legacy mode.

l Time: the construction was to start before the end

of 2003 and be completed at least six months

before the opening of the Olympic Games (i.e. six

months before 8 August 2008) to allow a sufficient

period for trial competitive events.

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

THE ARCHITECTURAL FORM

The Water Cube concept was inspired partly by its

neighbour, the Birds Nest Olympic Stadium. It sits

next to the glowing Birds Nest National Stadium,

and the two opposing shapes are in yin-yang

harmony, a key concept in Chinese culture. For

example, the Water Cube is blue against the

Stadiums red, water vs. fire, square vs. round, male

vs. female, earth vs. heaven. The two sites are

separated by a protected historic axis to Beijings

Forbidden City.

The Water Cube Aquatic Centre design portrays

the way in which humanity relates to water and the

harmonious coexistence of humans and nature,

which in Chinese culture is lifes ultimate blessing.

The flat ceiling is a feature that signifies peace and

stability. The entire square site accommodates the

clients requirements, effectively fixing a square

footprint for the building. The cube-shaped concept

is a subtle, thought-provoking design representing

the beauty and serenity of calm, untroubled water.

Figure 1 shows the Water Cube building from its

design imagination to reality.

ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT

FIGURE 1 The Water Cube from vision to reality: (a) the

design vision, (b) during construction and (c) the constructed facility

Source: www.beijingolympicsfan.com

The structural solution was based on the formation

of soap bubbles. Due to its complexity (the structure

consists of 22,000 steel members and 12,000

nodes), the entire building was modelled in four

dimensions. Numerous new techniques and pieces

of software were developed specifically for the

Water Cube project to generate the geometry,

create a physical prototype, optimize the structural

performance, analyse acoustics, smoke spread

and pedestrian egress, and provide construction

documentation in a fully automated 4D sequence.

The Water Cube is an insulated greenhouse that

maximizes the use of carbon-free solar energy for

both heating and lighting. The use of ethylene

tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE a kind of plastic) in lieu

of glass creates a superior acoustic environment,

reduces the weight of material supported by the

Lessons Learned from Managing the Design of the Water Cube National Swimming Centre 177

structure, improves seismic performance, and is

self-cleaning and recyclable. The roof collects and

reuses all rainwater that falls on the building. The

building is the result of integrating the technical

requirements of all the relevant engineering

disciplines (not the result of a single dominant one),

and without performance-based fire engineering (a

first for China) the Water Cube would not exist.

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

MANAGING THE WATER CUBES DESIGN

The Water Cube was the result of an international

design competition with 10 shortlisted participants,

judged by a panel of architects, engineers and

pre-eminent Chinese academics in 2003. The winner

was a Sydney-based joint venture (JV) team

consisting of Arup, PTW Architects and China

Construction Design International (CCDI). This team

was made up of more than 100 engineers and

specialists, spread across 20 disciplines and four

countries, and was led by Arup Project Management.

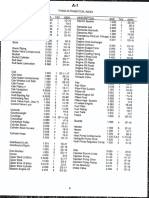

Figure 2 shows the composition of team members

involved in design and management, with particular

focus on personnel in project management. Arup

Project Management led and coordinated the design

process, and managed both the internal and external

interfaces.

Key threads of the project implementation

strategy covered everything from establishing a

communication strategy, through to the dynamics of

team leadership, a risk management strategy

focused on the complex and dynamic nature of the

Chinese market, and management of differences

between Chinese and Australian stakeholders.

It was a fast-track programme with design

delivered from competition stage through to a fully

approved scheme and continued through to the

official opening of the Water Cube. Furthermore, as

well as delivering a fully coordinated scheme design,

FIGURE 2 The Water Cube project design and management team

ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT

178 P. X. W. ZOU AND R. LESLIE-CARTER

it also involved regular handover of the design to the

Chinese design partners for detailing, while ensuring

that the technical approvals were all obtained and

that the innovative design was understood, accepted

and then constructed safely. Ensuring that the Water

Cube became a reality was achieved by establishing

and maintaining clarity of the design vision, and full

and transparent collaboration between the JV parties

Arup, PTW Architects and CCDI.

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

DEVELOPING DESIGN MANAGEMENT

STRATEGIES

Recognizing the scale and complexity of the

challenge, a two-day workshop with key design

team members was held to produce a roadmap for

the project. The agenda produced for the workshop

is shown in Figure 3.

The implementation plan workshop focused initially

on the need to articulate and communicate a very clear

project vision for the Water Cube design. This was

FIGURE 3 The Water Cube project implementation plan

ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT

intended to have multiple benefits. Most simply, the

vision would provide improved clarity and autonomy

to the design team members. This would help to

achieve a high-quality outcome in a very short period

of time, by allowing parallel streams of activities to

converge quickly and accurately. It was also hoped

that having a robust vision would greatly help to

achieve alignment and buy-in from other project

stakeholders. The workshop resulted in eight threads,

which were to form the basis for the projects future

development:

The site plan and urban design sitting opposite

the National Stadium in yin-yang harmony, the

two sites are separated by a protected historic axis

to Beijings Forbidden City. Red vs. blue, fire

vs. water, round vs. square, female vs. male,

heaven vs. earth.

l A building full of water made from bubbles a pure

combination of form and function.

l

Lessons Learned from Managing the Design of the Water Cube National Swimming Centre 179

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

A building harnessing the benefits of nature the

biomimicry of bubbles and the translation of

theoretical physics into a unique building form.

Portraying the harmonious coexistence of man and

nature.

A big blue green building this technically

performs well in terms of heat, light, sound,

structure and water; hence function is not

sacrificed in the name of art. Instead art is made

from function.

A 3D world the giant strides made in 3D design

and analysis technology, without which this project

simply could not have been fully conceived or

documented.

Next technology the use of high-tech materials to

minimize energy consumption.

Spiritually uplifting inside and outside the square

shape of the building reflects Chinese philosophies

of a square representing earth and a circle

representing heaven.

Total, equitable and transparent partnership

between Arup, PTW Architects and CCDI.

These eight threads were initially used as a guide to

brief the design team and partners. They proved

invaluable in discussions with external stakeholders

and local approval authorities, who were able to buy

into the overall vision and understand how they

could contribute to achieving that vision. Following

the workshop, the content of the Water Cube

implementation plan was approved. Establishing key

project management strategies and their rapid and

successful implementation were fundamental in

shaping the success of the Water Cube.

The binding thread in the success of the Water

Cube project was the quality and depth of

communication both internally and externally. As well

as day-to-day team communication and information

management processes, the communication strategy

established the vision and key messages, and how

these would be integrated into daily project life. The

strategy also encompassed the need for the

continuous incorporation of lessons learned in

dealing with stakeholders at different locations, and

with different cultures and languages. In doing so, it

provided a vehicle for relationship management and

stakeholder engagement.

Unique to this building is the direct comparison

with the model produced for the international design

competition, and the actual Water Cube when it

opened five years later. It is remarkable that a vision

and a reality aligned perfectly a very powerful

lesson in terms of the importance of capturing and

communicating a clear direction at the start of the

project.

INNOVATIONS

Several innovations were implemented in this project,

as discussed below.

DEVELOPING THE TOOLS TO DELIVER

The Water Cube was a catalyst for the establishment

of a range of bespoke project management planning

and monitoring tools needed to deliver such a large

multidisciplinary project, delivered across different

offices, and with a programme that demanded

reporting, monitoring and action to happen in real

time. A range of project management tools were

established for the Water Cube. These include

simple protocols for shared servers and email filing

between multiple offices, technical management of

project interfaces, safety in design (i.e. designing for

safety) and construction sequencing, through to

more complex programming applications that interface

with the cost monitoring system to provide detailed

forecasting and performance-reporting capabilities

such as resource management and earned-value

management.

INTERFACE MANAGEMENT

It was a challenge to coordinate 20 specialist

engineering disciplines, ensuring that the complex

interfaces of the Water Cube were properly

understood

and

documented.

The

project

management team introduced an interface

management strategy that divided the component

parts of the Water Cube into volumes defined by

physical and time boundaries, which were described

in a project volume register. Each volume was owned

by a sub-project team best placed to manage the

coordination. At the very start of the design process,

the project management team identified volumes and

assigned owners. An interface occurred when

anything touched or crossed a boundary. Initially all

ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT

180 P. X. W. ZOU AND R. LESLIE-CARTER

high- and low-level interfaces were identified and

captured on a register, and regular interface

management and coordination meetings were held

involving all parties (Figure 4). The external interfaces

were classified as either:

maintenance for equipment under warranty with

ongoing maintenance and replacement by the

operator, and the short-term responsibilities for

Olympic overlay compared with pre-Olympics

mode and then legacy mode.

Physical an identified and documented point or

plane common to two or more parties at which a

physical and potential performance

interdependency exists. Examples of physical

interfaces are the location of an underground

service, space allocation, duct route, etc.

l Functional an identified and documented

relationship between two parties at which a

performance independence exists. Examples of

functional interfaces are power requirements,

network connection, data connectivity, etc.

l Organizational and contractual an identified and

documented relationship between two parties at

which a delineation in scope or contractual

responsibility exists. Examples of organizational

interfaces include the development of details by

Chinese design partners CCDI based on Arup

scheme designs, or interfaces between civil

engineering and architectural landscaping

documentation, etc.

l Operational an identified and documented

relationship between two parties at which a

delineation in operational responsibility exists.

Examples of operational interfaces include

The management of interfaces became one of the

most

important

functions

of

the

project

management team during the design. Especially in

the short timeframe, the elimination of mistakes at

interfaces (e.g. missing or wrongly placed ducts,

service clashes) meant that the documentation

handed over to the other partners for further work

needed to be robust. In the longer term, it also

generated one of the largest possible savings in

construction cost compared with current practice.

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

DESIGNING FOR SAFETY AND 4D SEQUENCING

At the implementation plan workshop, the project

management team made a strong commitment to

explore the risk-prone activities likely to occur in the

construction of the Water Cube, and how to improve

safety by following a safety in design approach.

This included producing documentation that

would improve safety awareness, and suggesting

planned and logical methods for construction and

maintenance. Using the UK Construction Design and

Management (CDM) Regulations (1994 and 2007)

and relevant Australian legislation, the safety in

FIGURE 4 The volume strategy to resolve complex interfaces

ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

Lessons Learned from Managing the Design of the Water Cube National Swimming Centre 181

design approach was intended to ensure that unusual

hazards and risks (such as post-Olympic alterations to

the internal fit-out, and working-at-height hazards

involved in the maintenance of light fittings

or adjusting broadcasting equipment) were eliminated

or controlled at the design stage wherever possible.

The final hazard risk register was included with the

tender documentation along with recommendations

that it be incorporated into the safety management

plans for the various package contractors on site. It

also included graphical suggestions for construction

sequencing such as for the superstructure space frame.

The 3D structural model was linked with a sequential

timeline and became a 4D model.

THE PROJECT DESIGN AND MANAGEMENT

TEAM

RESOURCING A WINNING TEAM

Due to the short timeframes available to progress the

design from competition stage through to a fully

approved scheme, the team needed to mobilize very

quickly, with the right people. To achieve this, the

project management team began engaging selected

Arup engineers and specialists in a series of formal

and informal briefings about the Water Cube and the

potential opportunities for team members. By

generating a sense of excitement and anticipation,

key team members were identified.

LEADING CLEVER PEOPLE

Due to the innovative design concepts and materials

proposed for the Water Cube, the team needed to

include a high proportion of analysts and

programmers, capable of developing the new

analytical approaches and techniques required to

realize the project. In terms of the team dynamics and

leadership style, typically these professional individuals

resist being led, resist working to deadlines and dislike

centralized management structures, and leadership

needs to earn their respect. In recognition of this, the

project management team focused on providing these

people with a safe environment where they could

experiment (and fail), and on protecting them from the

administration distractions that occur in a project of

this scale. For example, specialist project managers

took responsibility for all project establishment, internal

reporting, commercial issues, and identifying and

coordinating the technical interfaces. This allowed

specialist designers to focus more purely on design.

HUNTING IN PACKS

To remove potential pinch points from specific key

staff becoming overloaded, and to allow technical

staff more freedom, project managers established

semi-independent teams with their own leadership,

to progress in parallel streams. These teams

included design, product research, stakeholder

engagement and commercial issues such as scope,

contract and fees: for example, establishment of

clear interfaces to allow the finalization of structural

geometry and research into the ETFE fac

ade

performance to proceed without holding up the

general space planning of the building. On the

back of the success of the Water Cube, it was

effective to employ a model of having specialist

project managers providing leadership, while giving

freedom to technical staff to add more value to the

design process. Embedding project management

into the business was more easily accepted, as the

specialist project managers also had technical

engineering backgrounds. In this way they were able

to contribute at all levels, rather than ever being

perceived as a non-technical overhead.

ACHIEVING PROJECT OUTCOMES

This section discusses project outcomes in relation to

client expectations.

CREATE THE BEST OLYMPIC SWIMMING

VENUE

Designing the fastest of fast pools for Beijing was

very much part of the design teams proposals in the

competition entry. Most obviously, the pool design

minimized turbulence for swimmers through a

constant 3m pool depth (compared with 2m for the

Athens Olympics), extra wide pool lanes and empty

lanes at each side, lane separators designed to

dissipate wake and perimeter gutters designed for

wave surge control. There were also unseen allies

designed in, such as maintaining the right water

chemical balance and water temperature critical to a

swimmers performance, and a displacement air

conditioning system designed to maintain a layer of

fresh oxygenated air across the pool surface.

ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

182 P. X. W. ZOU AND R. LESLIE-CARTER

One of the less tangible factors was the energy

of the Water Cube. The energy is, in fact,

thoughtfully designed, not just through the uplifting

experience of the Water Cube internal space, but

also through the back-of-house areas, warm-up and

warm-down facilities for the athletes, the positioning

and proximity of the 17,000-seat spectator areas,

and the lighting, acoustics and air quality of the

building.

The Water Cube amazed visitors and inspired

athletes at the 2008 Olympic Games, hosting the

swimming, diving and water polo events. The

Olympic events opened at the pool meaning the

Water Cube immediately become the global face of

the Games, and a total of 42 gold medals were

awarded there. The fastest times in 21 of the 32

Olympic swimming events now belong to the Water

Cube in total, 22 world records were set in what is

now the fastest pool in the world.

In the short time since its opening, the Water Cube

has become one of the iconic projects of the 21st

century a representation of a new Beijing and, by

extension, a new China. It showcases Chinas

determination to establish itself as a leading

destination for world sporting events.

SPEND NO MORE THAN US$100M

The construction contract for the project was let at

US$100 million, which was the budget set for the

Water Cube Aquatic Centre before the design

competition. There was an additional US$10 million

allocated to its conversion post-Olympics, removing

10,000 seats and building additional commercial

space. To design a building for this budget is a

remarkable feat considering that it has 70,000m2 of

internal floor space, 100,000m2 of cladding and all

the complex plants required to run three competition

pools and a very large leisure centre.

As part of setting the project objectives, the

project management team led a value management

exercise to optimize the space planning of the Water

Cube without compromising any of the project

objectives. This structured approach led to a

reduction of building area and costs of nearly 10%,

and set the tone for an efficient building design that

the Beijing Municipal Government had confidence

could be delivered within the budget.

ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT

One key factor built into the design is its

buildability despite the buildings apparent

complexity and because the structure is based on

repetitive geometry, the sub-components repeat

across the building. There are only four different

nodal geometries, three typical member lengths and

22 different ETFE pillow shapes. This deliberate

approach greatly reduced the time required for

production and installation, and the fabrication and

installation costs.

The Water Cube is flexibly designed to reduce

from 17,000 seats to 7000 seats post-Olympics,

which will allow for the addition of commercial

space inside and a switch to the ongoing legacy

operation of the building. The Water Cube will still

be the National Aquatic Centre with the facilities we

have seen at the Olympics. However, its main future

revenue will be from a huge leisure pool the size of

four Olympic pools hence the Water Cube will be

socially and economically sustainable as well as

environmentally sustainable.

Alongside the Birds Nest, the Water Cube is the

representation of Beijings emergence as a truly

global city. The greatest gift to Beijing, generated

from the public exposure and excitement around its

Olympic venues, will be the social and economic

benefits that will now follow.

CREATE A GREEN GAMES

Beijing has for a long time been blighted by heavy air

pollution from factories and coal-fired power stations

within the city itself, and an unstoppable growth of

motor traffic pushing its transport infrastructure

towards permanent gridlock. Today, more than 1000

new cars come onto the roads of Beijing every day. In

the build-up to the Olympic opening ceremony, the

question was what Beijing could achieve in a very short

period of time and if the national stadium would be

shrouded in smog on the first day of the Games.

As well as contributing to the green Games

through its sustainable design initiatives, the Water

Cube is raising environmental awareness in society

more broadly through its unique design thinking. It

responds to the question: How should a building

best harness the benefits of nature? The answer

was to design and deliver an insulated greenhouse

using minimal materials. The resulting building

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

Lessons Learned from Managing the Design of the Water Cube National Swimming Centre 183

naturally heats the swimming pools, lights itself,

catches and stores rainwater, and can resist some of

the largest seismic forces in the world.

The design and construction of the Water Cube

aimed at improving the ecological environment. It

was a shining light in the national effort to drastically

improve the environmental quality of Beijing in the

run-up to the Olympics. The Water Cube is not just

an exercise of symbolism. In terms of iconic Beijing

buildings, the Water Cube represents a real

transition from the traditional monumental communist

architecture around Tiananmen Square to a future

that is more about conserving resources, building

more delicately and sustainably.

Of course, China needs to invest in long-term

environmental solutions, and the hope is that after

the Olympic coming-out party, the Water Cube will

act as an inspiration for future development, so that

local architects and engineers will channel their

ideas and the unstoppable rate of development in

Beijing into quality design solutions that are

sustainable.

CREATE A HIGH-TECH GAMES

The Olympic Games was a window for Beijing to

showcase its high-tech achievements and innovative

capacity. The Water Cube design adopted the

worlds best technology practices to ensure that the

swimming events were hosted in an ultra high-tech

environment. The design teams used their global

knowledge resources to design a fast pool,

including research and negotiations with Federation

Internationale de Natation (FINA) regarding

improvement in pool shape, water filtration and

audiovisual projections. The pool was deliberately

opened six months before the Olympics to allow for

competition-level testing and optimization of the

conditions for competitors.

CREATE A PEOPLES GAMES

Hosting of the Olympic Games was an opportunity to

popularize the Olympic spirit, promote traditional

Chinese culture, and showcase the history and

development of Beijing as well as the friendliness

and hospitality of its citizens. The Water Cube is

thought of as the peoples venue in Beijing, receiving

more than a million votes from the people of China

during the International Design Competition. No

matter where they are from, people seem to share a

common reaction towards the Water Cube: it has

a soothing power and a calming effect. The square

shape of the building reflects the Chinese

philosophy of a square representing earth and a

circle representing heaven.

The Water Cube has acted as a bridge for cultural

exchanges and has deepened the understanding,

trust and friendship among project team members

and stakeholders. This was achieved by establishing

and maintaining clarity of the design vision,

communicating that vision to project stakeholders

with differing cultural expectations, and the

outstanding collaboration between the JV parties

Arup, PTW Architects and CCDI. The design in

essence epitomizes the wishes, hopes and dreams

of the Chinese people, and because it was chosen

by them, it belongs to them and is something they

can be proud of for centuries to come.

LESSONS LEARNED

LESSON 1 FORMING AN INTERNATIONAL

PARTNERSHIP

The unusual thing about the Beijing Olympics is that

international designers were invited to participate at

all which was not the case in Sydney and other

previous Olympic host cities. One reason was that

the challenge was of such a huge scale that Beijing

recognized it needed solutions from both home and

abroad. This attitude set the tone for a genuine

two-way collaboration on the Water Cube where

Western and Eastern perspectives worked together

with mutual respect and openness.

Generally speaking, project-oriented JV is one of

the major entrance models of international companies

for undertaking business in countries other than

their motherhood (Ng et al., 2007). This is partly

because the specific political and macro-economical

conditions in the host country may significantly

impact project performance. Furthermore, the

unique characteristics of each project are highly

associated with JV performance, and appropriate

strategies should be developed to handle particular

risks and problems associated with the project

(Ozorhon et al., 2007; Zou et al., 2007; Zou and

Wong, 2008). When focusing on international

ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

184 P. X. W. ZOU AND R. LESLIE-CARTER

construction projects in China, the five most important

factors leading to JV success are selection of

partners, clear statement of JV agreement, obtaining

information about potential partners, partners

objectives and control of the ownership of the capital

(Gale and Luo, 2003).

The Water Cube team also came about after some

very deliberate relationship building by Arup and PTW

in the build-up to the international design competition.

In 2003, Sydney had the halo effect of having just

hosted the best Olympic Games ever and what was

regarded as the fastest pool ever, which had also

been designed by Arup and PTW. Arup had also

recently designed the Shenzhen Aquatic Centre from

its Sydney office, and hence understood some of the

challenges of working in China as an international firm.

Specifically, the opportunity to align with Chinese

design partners CCDI and their parent company

CSCEC (Chinas biggest construction firm) came

about from building up relationships and Arups

reputation through a series of visits to China to

present credentials, to present the engineering

behind fast pools and to discuss the opportunities

for collaboration for the Beijing Games.

The legacy of the authenticity of the team is the

fact that the Water Cube was generated by equally

integrating the requirements of Arups engineering,

PTWs space planning and Chinese cultural

influences on the architecture from CCDI. It was not

the result of any one single dominant party, which

remains a powerful statement in terms of the

outstanding collaboration established among this

international partnership.

LESSON 2 MANAGING CULTURAL RISKS AND

DIFFERENCES

When managing projects in China, a particularly

important issue that foreign firms need to face is

how to manage the cultural differences (Zou et al.,

2007, 2009), especially for companies with

traditional Western culture backgrounds. Different

cultures may lead to significant differences in project

management styles and capacities (Zwikael et al.,

2005). Understanding organizational and national

culture, cross-cultural communication, negotiation

and dispute resolution are considered to be the

most important issues for the project management

ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT

process in China, where personal relationships are

very important and teamwork is preferred to make

decisions (Low and Leong, 1999). For the Water

Cube, how to manage communication both internally

and externally, as well as how to handle the

relationship with all parties involved in the project,

was critical to the success of the project.

For the cross-cultural management of construction

projects in China, one of the most important issues is

guanxi (Zou and Wong, 2008), which refers to

relationships or social connections based on mutual

interests and benefits (Yang, 1999). In general,

guanxi and Western relationship marketing do share

some basic characteristics as mutual understanding,

but they have quite different underlying mechanisms

(Arias, 1998; Zou et al., 2009). In contrast with

relationship marketing, guanxi works at a personal

level on the basis of friendship, and affection is a

measure of the level of emotional commitment and

the closeness of the parties involved (Wang, 2005).

When doing business or managing projects in China,

developing an effective guanxi with local Chinese

partners is a key factor for most companies, in spite

of the type and scope of projects. However, because

of the complexity of guanxi, some guanxi issues are

more important than others for certain types of

projects. For example, the external coalitions among

guanxi partners that can contribute more resources to

a firms survival are certainly more important than

coalitions that contribute fewer resources. Further,

guanxi strategies should be dynamic and changing

along with business timing and location (Su et al., 2007).

Ling et al. (2007a) suggested that in order to

implement a superior project management practice

in China, international construction companies should

increase their financial strength to overcome the

blank period before making a profit. International

companies should also prepare a high-quality

contract and project schedule as early as possible

during the pre-contracting and planning stage. To

control cost, time and quality issues during the

construction stage, international firms should

control cultural difference risks and language barrier

risks to avoid misunderstanding, provide adequate

equipment and employ qualified workmen. Further,

Ling et al. (2007b) pointed out the importance of

minimizing claims or disputes in the contract,

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

Lessons Learned from Managing the Design of the Water Cube National Swimming Centre 185

adequate provision of equipment to deliver the

service, strong financial strength and management,

controlling resources and cost, appointing qualified

professional staff, good quality control and

management plans, and having more face-to-face

communication

than

written

communication.

Likewise, Gunhan and Arditi (2005) stated that a

good track record, project management capability, a

broad international network, technology, and

material and equipment advantages are the most

important strengths of international construction

companies for entering a new market.

In international construction project management,

while companies face threats from key employee

losses, financial resources, international economy

fluctuation, foreign competition and cultural

differences are also some other major risks (Ling

et al., 2007b). Further, it is worth noting that project

management in China is still immature, with the

main problems being lack of qualified and

experienced project management practitioners,

conflict between client and project management

companies, distorted competition in the project

management market and the time of appointing

project management companies (Liu et al., 2004).

For the Water Cube project, what was more

challenging for the project management team than the

technical aspects, and ultimately far more rewarding,

was learning and understanding the business culture

and context in China. It was not only foreign to the

team at the start of the project, but also highly difficult

to read. To resolve this problem, implementation plan

workshops and follow-up sessions were held with all

the parties involved in designing the project,

particularly with Chinese team members, to agree on

the approach to the early management of difference.

The workshops served as a platform for bringing the

team together to exchange ideas and information and

discussions of key issues. These workshops partly

focused on maintaining leverage over commercial

arrangements, but mainly looked at how to minimize

and manage the risks of the specific differences in

norms, practices and expectations through project

implementation.

The complex and dynamic nature of the Chinese

market, particularly in the context of the Olympics,

meant that the risks associated with delivering the

Water Cube project could not be underestimated.

Beijings lack of regulatory transparency, regional

differences and a relationship-based business

culture were among the factors that made China a

challenging project environment.

The project management team identified a diverse

range of risks, trying to understand and plan an

approach to the project in the unfamiliar context of

Chinas legal, social, cultural, economic and

technological environment. Other than the commercial

risk of delayed payment, the key risks identified were

social how Chinas business culture may affect the

relationships and dynamics within the international

Water Cube team and with the external stakeholders

involved in approving the design concept.

Social risks such as cultural misunderstandings

could have completely derailed or significantly

delayed the Water Cube project. Relationship

building is fundamental in Chinese business; hence

understanding guanxi a form of social networking

and how to authentically cultivate and manage it

was vital to the project management team. Other

important factors in the approach included

emphasizing the teams international reputation and

the depth and diversity of its activities and locations.

Arup also planned to ensure that all its interactions

with Chinese stakeholders involved giving them the

highest possible quality of service, in terms of both

the material issued and the staff directly involved

with them. For example, well-respected senior

engineers from its Beijing and Hong Kong offices

were directly involved at key stages of the approval

process. Their influence and local knowledge of the

Chinese legislation, coupled with their involvement

in other high-profile Olympic projects in Beijing,

were leveraged to convince some conservative

authorities to accept a range of innovative

approaches to the engineering design that did not

follow the prescriptive rules of the Chinese building

codes. This was the number one risk in the

early stages of the project, and the formal

approval of the engineering design in early 2004 set

a major precedent and direction for other Olympic

projects.

Another example was the commercial negotiations.

The project has been a financial success in that it

made an acceptable profit despite the considerable

ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

186 P. X. W. ZOU AND R. LESLIE-CARTER

risks of working on such a fast-track project, with

international partners and stakeholders, involving

such groundbreaking design techniques and

materials. This is largely because the project

managers were very specific during contract

negotiations to clearly define their scope of services

and the interfaces with Chinese design partners, and

were robust in contract negotiations that removed

the project management company (i.e. Arup) from

some of the post-Olympic payment milestones that

were unrelated to the project scope. By deliberately

resolving any potential conflicts early, the project

management was able to sign a contract and

facilitate a smooth and seamless handover to the

Chinese partners with clearly understood and

accepted interfaces.

LESSON 3 LACK OF INVOLVEMENT IN THE

CONSTRUCTION STAGE

One aspect that could have been improved was being

able to secure a role for the project management team

during the construction phase and also post-Olympics

for conversion to legacy mode. During contract

negotiations, the Chinese partner CCDI wanted to

limit its overall fee bid by resourcing elements of the

detailed design and site supervision locally from

Beijing. While Arups project management team

successfully managed to ring-fence its design role,

its proposal to maintain even a skeleton supervisory

role during construction to help ensure the design

intent was achieved was seen as an avoidable cost

by the Chinese design partners. So the project

management team was not formally involved in the

construction stage, and this led to several issues

regarding the interface and integration between

design ideas and site construction. For example, for

the steelwork and ETFE fac

ade, the project

management company sent staff to Beijing at its

own cost, but this became increasingly difficult as

security measures tightened during the months

leading up to the Water Cubes opening. Further,

some modifications to minor details were decided

on site, generally driven by changes to overlay and

operator requirements. There are examples where

these decisions are not as the project management

would have proposed had it been involved. This lack

of involvement of the project management

ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT

company in construction had some implications on

quality.

Less tangible than the quality of construction

details was the potential effect on the project

management team members of being partially

excluded from the construction stage activities. It is

a fundamental part of projects that designers get

enormous satisfaction from seeing their designs

become reality. There is traditionally an ongoing role

for engineers responding to site issues, attending

coordination meetings with contractors, and being

involved in final commissioning and handover. All

these are important parts of the ownership that

engineers ascribe to their work, and their motivation

to be part of future teams.

To rectify this, the project management team

developed an internal communication strategy at the

outset of the project, which included engaging staff

before and during the project through presentations,

briefings, newsletters and regular celebrations of

milestones. However, it was only after the

construction work had commenced and the role

diminished that the project management team

realized that there was a gap in their involvement in

actually experiencing the Water Cube being built.

The situation was highlighted even further by the

geographical separation from Beijing, and the

ever-increasing levels of security and bureaucracy

about site access.

Ultimately in the case of the Water Cube with its

crystal-clear design vision and high profile Arups

lack of involvement during the construction stage

did not have a significant negative effect on either

the quality of the outcome or the level of ownership

among the design team. However, Arups project

managers have issued a report to CCDI highlighting

this as a valuable lesson learned, and quantifying the

added value it could have brought to more than

offset any additional fees.

LESSON 4 ESTABLISHING A LEGACY

reads, there are only three things

As the great cliche

that matter when it comes to the Olympic Games:

Legacy, Legacy, Legacy. There were legacy

building opportunities that directly benefited the

team relationship and the final outcome of

the Water Cube. An ongoing challenge during the

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

Lessons Learned from Managing the Design of the Water Cube National Swimming Centre 187

contract negotiations was the inclusion of standard

clauses to protect intellectual property and

copyright over design ideas and documentation. At

the implementation planning workshop, project

managers presented the benefits of embracing a

very clear and simple policy that collaboration

between all design partners be total and completely

transparent. This was fundamental to establishing

and maintaining trust and respect at the start of the

project. In design terms, this involved accepting that

the concepts and analytical approaches that were

developed would become an important knowledge

legacy to help the design partner develop its

capabilities. In practical terms, it also meant that the

handovers to the partners were genuinely open.

The first legacy of the building is the ETFE fac

ade

design, construction and performance. Team

members spent a week interviewing ETFE tenderers

and being challenged by a panel of Chinese

academics on various aspects of the ETFE fac

ade

design and performance. As an extension to the

deliberate legacy building approach, Arup lobbied

that the ETFE contractors and the people of Beijing

would benefit by investing in local manufacturing and

processing facilities in Beijing, which the winning

tenderer

accepted

and

implemented.

This

guaranteed local training and employment in the

short term, but also led to a long-term local capability

to produce an innovative material likely to feature

heavily in Beijings ongoing development programme.

Another often-debated legacy is the legacy of a

totally shared ownership of the Water Cube concept.

The philosophy agreed on at the implementation

planning workshop, and one that resonated with all

the stakeholders during the project, is that the box

of bubbles concept for the Water Cube was

generated by equally integrating the requirements of

Arups engineering, PTWs space planning and

Chinese cultural influences on architecture from

CCDI. It was not the result of any one single

dominant party. With such an iconic building, this

was and remains a powerful statement in terms of

the successful collaboration established between

the three project partners.

Finally, for the project management team and

other team members involved, the relationships they

have made and the satisfaction they have

achieved from being part of such a wonderful

project have provided a very genuine legacy. As well

as achieving critical acclaim, the project has

proved to be a successful investment in developing

a project management approach to establishing

and leading winning teams, managing relationships

with stakeholders across cultures, developing project

management

processes

required

on

major

multidisciplinary

projects

and

technological

improvements in our immersive 3D modelling

capability. These have since been used to great

effect on many other Arup projects.

CONCLUSIONS

This article has discussed the major lessons learned

from managing the design of the Water Cube

Aquatic Swimming Centre for the Beijing 2008

Olympic Games. Many aspects of the Water Cube

project delivery were new and unique to the project

management team, which required innovative design

and management strategies and solutions. Virtually

every aspect has been a lesson learned of some

sort. It is important that these lessons learned be

captured and successfully taken forward for

development on future projects.

It is found that the design and management of a

complex international project like the Water Cube

must be innovative so as to meet client

expectations. These may include developing project

implementation

strategic

plans,

developing

interface management strategies and designing for

safety; after all the most important strategy is to

recruit and lead clever people who may resist

being led and resist working to deadlines. It was

found that the complex and dynamic nature of the

Chinese market, its lack of regulatory transparency

and a relationship-based business culture were

among the factors that made China a challenging

project

environment.

As

such,

cultural

understanding and relationship (guanxi) building

were fundamental strategies in responding to these

challenges. It was also found that there is a need

for

the

design

and

management

teams

involvement in the construction stage to ensure the

conversion of design into reality and construction

quality as well as the fulfilment of professional and

personal satisfaction.

ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT

188 P. X. W. ZOU AND R. LESLIE-CARTER

REFERENCES

Arias, J.T.G., 1998, A relationship marketing approach to guanxi, European

Journal of Marketing 32(1/2), 145156.

China: A hierarchical stakeholder model of effective guanxi, Journal of

Business Ethics 71(3), 301 319.

Gale, A. and Luo, J., 2003, Factors affecting construction joint ventures in

Her Majestys Stationery Office, HMSO, 1994, Construction (Design and

China, International Journal of Project Management 22(1), 33 42.

Management) Regulations, Statutory Instrument No. 3410, London,

Gunhan, S. and Arditi, D., 2005, Foreign market entry decision model for

construction companies, Journal of Construction Engineering and

Management, ASCE 131(8), 928937.

Ling, F.Y.Y., Low, S.P., Wang, S.Q. and Egbelakin, T.K., 2007a, Foreign

firms strategic and project management practices in China. International

construction management China, in W. Hughes (ed), Proceedings of

Construction Management and Economics: Past, Present and Future,

Downloaded by [University of Malaya] at 07:54 05 March 2015

Su, C., Mitchell, R. and Sirgy, M.J., 2007, Enabling guanxi management in

Reading, University of Reading, CME 25 Conference, 16 18 July 2007.

Ling, F.Y.Y., Low, S.P., Wang, S.Q. and Lim, H.H., 2007b, Key project

management practices affecting Singaporean firms project performance

in China, International Journal of Project Management 27(1), 59 71.

Liu, G.W., Shen, Q.P., Li, H. and Shen, L.Y., 2004, Factors constraining the

HMSO.

Her Majestys Stationery Office, HMSO, 2007, Construction (Design and

Management) Regulations, Statutory Instrument No. 320, London,

HMSO.

Wang, C.L., 2005, Guanxi vs. relationship marketing: exploring underlying

differences, Industrial Marketing Management 36(1), 81 86.

Yang, M.M., 1999, Gift, Favours, Banquets: The Art of Social Relationship in

China, Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press.

Zou, P.X.W. and Wong, A., 2008, Breaking into Chinas design and

construction market, Journal of Technology Management in China 3(3),

279 291.

Zou, P.X.W., Wong, A. and Tan, E.X., 2009, Opportunities and risks of

development of professional project management in Chinas construction

Australian firms in the Chinese design and construction management

industry, International Journal of Project Management 22(3), 203211.

market, Proceedings of 34th Australasia Universities Building

Low, S.P. and Leong, C.H.Y., 1999, Cross-cultural project management for

international construction in China, International Journal of Project

Management 18(2000), 307 316.

Ng, P.W.K., Lau, C.M. and Nyaw, M.K., 2007, The effect of trust on

international joint venture performance in China, Journal of International

Management 13(4), 430 448.

Ozorhon, B., Arditi, D., Dikmen, I. and Birgonul, M.T., 2007, Effect of host

Educators (AUBEA) Conference, Barossa Valley, South Australia,

Australia, 7 10 July 2009, abstract on p2 hard copy proceedings, Full

paper in CD ROM.

Zou, P.X.W., Zhang, G.M. and Wang, J.Y., 2007, Understanding the key

risks in construction projects in China, International Journal of Project

Management 25(6), 601 614.

Zwikael, O., Shimizu, K. and Globerson, S., 2005, Cultural differences in

country and project conditions in international construction joint ventures,

project management capabilities: a field study, International Journal of

International Journal of Project Management 25(8), 799806.

Project Management 23(6), 454 462.

ARCHITECTURAL ENGINEERING AND DESIGN MANAGEMENT

También podría gustarte

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2099)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (73)

- Directional OCDocumento301 páginasDirectional OCurcalmAún no hay calificaciones

- Carestream DryView 5700 PDFDocumento44 páginasCarestream DryView 5700 PDFJose Quisca100% (1)

- Biogas Calculator TemplateDocumento27 páginasBiogas Calculator TemplateAlex Julian-CooperAún no hay calificaciones

- Foundation LayoutDocumento1 páginaFoundation LayoutrendaninAún no hay calificaciones

- VGS 8.1.2 Rev.20 - UTDocumento29 páginasVGS 8.1.2 Rev.20 - UTPaul-Petrus MogosAún no hay calificaciones

- Operating Instructions, FormulaDocumento35 páginasOperating Instructions, FormulaandymulyonoAún no hay calificaciones

- FH400 73158464 Pca-6.140Documento431 páginasFH400 73158464 Pca-6.140IgorGorduz100% (1)

- Overseas Project of the Year 2008: Water Cube BeijingDocumento8 páginasOverseas Project of the Year 2008: Water Cube BeijingDandOooOneAún no hay calificaciones

- Problemes of Process ControlDocumento17 páginasProblemes of Process ControlThomas Teh Qian HuaAún no hay calificaciones

- East Asian StudiesDocumento49 páginasEast Asian StudiesThomas Teh Qian HuaAún no hay calificaciones

- Nikon D70 ManualDocumento219 páginasNikon D70 ManualTonyologyAún no hay calificaciones

- Wilson Plot MethodDocumento13 páginasWilson Plot MethodThomas Teh Qian HuaAún no hay calificaciones

- Estimating A VARDocumento7 páginasEstimating A VARNur Cholik Widyan SaAún no hay calificaciones

- Nikon D70 ManualDocumento219 páginasNikon D70 ManualTonyologyAún no hay calificaciones

- Glucose Solution ViscosityDocumento13 páginasGlucose Solution ViscosityThomas Teh Qian Hua100% (1)

- Codex SeraphinianusDocumento30 páginasCodex SeraphinianusThomas Teh Qian HuaAún no hay calificaciones

- Cara Menulis Rujukan-Apa StyleDocumento18 páginasCara Menulis Rujukan-Apa StyleWan AqilahAún no hay calificaciones

- Lagrange SampleDocumento1 páginaLagrange SampleThomas Teh Qian HuaAún no hay calificaciones

- Schollarship 2011Documento6 páginasSchollarship 2011Thomas Teh Qian HuaAún no hay calificaciones

- Annual Report 2012Documento125 páginasAnnual Report 2012Thomas Teh Qian HuaAún no hay calificaciones

- Conventional and Non-Conventional Energy Resources of India: Present and FutureDocumento8 páginasConventional and Non-Conventional Energy Resources of India: Present and FutureAnkit SharmaAún no hay calificaciones

- Fosroc Conbextra EP10: Constructive SolutionsDocumento2 páginasFosroc Conbextra EP10: Constructive SolutionsVincent JavateAún no hay calificaciones

- Dow Corning (R) 200 Fluid, 50 Cst.Documento11 páginasDow Corning (R) 200 Fluid, 50 Cst.Sergio Gonzalez GuzmanAún no hay calificaciones

- Ornl 2465Documento101 páginasOrnl 2465jesusAún no hay calificaciones

- NUSTian Final July SeptDocumento36 páginasNUSTian Final July SeptAdeel KhanAún no hay calificaciones

- Assessment Clo1 Clo2 Clo3 Clo4 Clo5 Plo1 Plo2 Plo2 Plo1Documento12 páginasAssessment Clo1 Clo2 Clo3 Clo4 Clo5 Plo1 Plo2 Plo2 Plo1Ma Liu Hun VuiAún no hay calificaciones

- Distribution A9F74240Documento3 páginasDistribution A9F74240Dani WaskitoAún no hay calificaciones

- Melter / Applicators: Modern Cracksealing TechnologyDocumento16 páginasMelter / Applicators: Modern Cracksealing TechnologyEduardo RazerAún no hay calificaciones

- Murray Loop Test To Locate Ground Fault PDFDocumento2 páginasMurray Loop Test To Locate Ground Fault PDFmohdAún no hay calificaciones

- Minor Project Report On Efficiency Improvement of A Combined Cycle Power PlantDocumento40 páginasMinor Project Report On Efficiency Improvement of A Combined Cycle Power PlantArpit Garg100% (1)

- Seminar ReportDocumento30 páginasSeminar Reportshashank_gowda_7Aún no hay calificaciones

- Easygen-3000 Series (Package P1) Genset Control: InterfaceDocumento102 páginasEasygen-3000 Series (Package P1) Genset Control: InterfacejinameAún no hay calificaciones

- End All Red Overdrive: Controls and FeaturesDocumento6 páginasEnd All Red Overdrive: Controls and FeaturesBepe uptp5aAún no hay calificaciones

- Grounding Vs BondingDocumento2 páginasGrounding Vs BondingVictor HutahaeanAún no hay calificaciones

- Microsoft Word - Transistor Models and The Feedback Amp - Docmicrosoft Word - Transistor Models and The Feedback Amp - Doctransistor - Models - and - The - FbaDocumento14 páginasMicrosoft Word - Transistor Models and The Feedback Amp - Docmicrosoft Word - Transistor Models and The Feedback Amp - Doctransistor - Models - and - The - FbashubhamformeAún no hay calificaciones

- 2:4 Decoder: DECODER: A Slightly More Complex Decoder Would Be The N-To-2n Type Binary Decoders. These TypesDocumento6 páginas2:4 Decoder: DECODER: A Slightly More Complex Decoder Would Be The N-To-2n Type Binary Decoders. These TypesPavithraRamAún no hay calificaciones

- Rockaway Beach Branch Community Impact StudyDocumento98 páginasRockaway Beach Branch Community Impact StudyHanaRAlbertsAún no hay calificaciones

- Motorola's TQM Journey to Six Sigma QualityDocumento19 páginasMotorola's TQM Journey to Six Sigma QualityKatya Avdieienko100% (1)

- Civil 3 8sem PDFDocumento43 páginasCivil 3 8sem PDFG0utham100% (1)

- Symfony 2 The BookDocumento354 páginasSymfony 2 The BookYamuna ChowdaryAún no hay calificaciones

- Gps VulnerabilityDocumento28 páginasGps VulnerabilityaxyyAún no hay calificaciones