Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 2014 Morgan 246 56

Cargado por

Frontier JuniorDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 2014 Morgan 246 56

Cargado por

Frontier JuniorCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

539835

research-article2014

FOAXXX10.1177/1088357614539835Focus on Autism and Other Developmental DisabilitiesMorgan et al.

Article

Impact of Social Communication

Interventions on Infants and

Toddlers With or At-Risk for

Autism: A Systematic Review

Focus on Autism and Other

Developmental Disabilities

2014, Vol. 29(4) 246256

Hammill Institute on Disabilities 2014

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1088357614539835

focus.sagepub.com

Lindee J. Morgan, PhD1, Emily Rubin, MS2, Jaumeiko J. Coleman, PhD3,

Tobi Frymark, MA3, Beverly P. Wang, MLIS3, and Laura J. Cannon, BA4

Abstract

This is a systematic review of the impact of communication interventions on the social communication skills of infants and

toddlers with or at-risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD). A priori clinical questions accompanied by specific inclusion

and exclusion criteria informed the extensive literature search that was conducted in multiple databases (e.g., PubMed).

Twenty-six studies were accepted for this review. Outcomes were reported by social communication category (i.e.,

joint attention, social reciprocity, and language and related cognitive skills) and communication developmental stage (i.e.,

prelinguistic, emerging language). Primarily positive treatment effects were revealed in the majority of outcome categories

for which social communication data were available. However, the presence of intervention and outcome measure

heterogeneity precluded a clear determination of intervention effects. Future research should address these issues while

also evaluating multiple outcomes and adding a strong family component designed to enhance child active engagement.

Keywords

autism, autism spectrum disorder, social communication, pervasive developmental disorder, speech-language pathology,

intervention

In 2012, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Associ

ations (ASHAs) National Center for Evidence-based

Practice was charged with developing an evidence-based

systematic review (EBSR) on the impact of communication

interventions for infants and toddlers with or at-risk for

ASD in collaboration with experts in the field. An EBSR

addresses unambiguous and specific questions on a particular topic; clearly explains the methods and criteria used to

locate and select studies for inclusion; and entails reviewing, critiquing, and integrating pertinent information from

the selected studies in an effort to provide a synthesis of the

current best evidence (Dollaghan, 2007).

Previous systematic reviews have examined the impact

of communication treatments on various skill areas in wide

age groups of children with ASD (e.g., National Research

Council [NRC], 2001; Schertz, Reichow, Tan, Vaiouli, &

Yildirim, 2012; Wallace & Rogers, 2010). In reviews that

addressed infants and toddlers, lack of empirically validated

treatments for infants and toddlers with ASD (Wallace &

Rogers, 2010) and great heterogeneity in findings (e.g.,

Schertz et al., 2012) precluded ascertaining generalized

treatment effects. Clearly, a closer examination of the evidence pertaining to social communication interventions

used with young children is warranted.

To better elucidate the treatment effects of social communication interventions, a framework devised by ASHA

was adopted (ASHA, 2006). The framework groups intervention goals by social communication outcome categories

(i.e., joint attention, social reciprocity, language and related

cognitive skills, behavior and emotional regulation) across

communication developmental stages (i.e., prelinguistic,

emerging language). The social communication outcome

categories represent core areas of difficulty for individuals

with ASD, whereas the selected developmental stages

reflect the age of the population discussed in this EBSR.

Joint attention is establishing shared attention, social reciprocity entails maintaining interactions by taking turns, language and related cognitive skills applies to the use and

1

Florida State University Autism Institute, Tallahassee, USA

Marcus Autism Center, Atlanta, GA, USA

3

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Rockville, MD, USA

4

University of Maryland, College Park, USA

2

Corresponding Author:

Jaumeiko J. Coleman, American Speech-Language-Hearing Association,

National Center for Evidence-Based Practice, 2200 Research Blvd.,

#245, Rockville, MD 20850, USA.

Email: jcoleman@asha.org

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at Universitas Gadjah Mada on April 10, 2015

247

Morgan et al.

understanding of nonverbal and verbal communication, and

behavioral and emotional regulation is the successful regulation of ones emotions and behaviors (ASHA, 2006). In

regard to the communication developmental stages applicable to infants and toddlers, prelinguistic pertains to the

use of nonverbal communicative strategies, such as gestures; and emerging language is the burgeoning use of verbal language (ASHA, 2006). The aim of this EBSR was to

further evaluate the impact of communication interventions

on social communication skills of infants and toddlers with

ASD aged 36 months or less. The clinical questions for this

EBSR follow:

Clinical Question 1: What are the effects of communication interventions on joint attention outcomes for

children 36 months old or less at-risk for or diagnosed

with ASD?

Clinical Question 2: What are the effects of communication interventions on social reciprocity outcomes for

children 36 months old or less at-risk for or diagnosed

with ASD?

Clinical Question 3: What are the effects of communication interventions on language and related cognitive

skill outcomes for children 36 months old or less at-risk

for or diagnosed with ASD?

Clinical Question 4: What are the effects of communication interventions on behavioral and emotional regulation outcomes for children 36 months old or less at-risk

for or diagnosed with ASD?

Method

To complete this EBSR, a multi-step approach was taken

including (a) identification of peer-reviewed articles that

address the population of interest and clinical questions;

(b) evaluation of the methodological rigor of accepted studies; (c) grouping outcomes as prelinguistic or emerging language within one of the following areas: joint attention,

social reciprocity, language and related cognitive skills, or

behavioral and emotional regulation; (d) computing effect

sizes and assigning associated magnitude of effect descriptors; and (e) assessing the findings in relation to the clinical

questions. One author conducted a literature search in 25

electronic databases (e.g., PubMed, ERIC, Research

Autism) using key words related to autism, autism spectrum

disorder (ASD), pervasive developmental disorder (PDD),

speech-language pathology, and treatment (the complete

list of databases, key words, and search strategy is available

on request). Two authors independently assessed the titles

and abstracts of all articles. The references of all full-text

articles were scanned to identify additional relevant studies

and a search for prolific authors was also completed. Two

authors also independently assessed each included study for

methodological rigor; any disagreements about critical

appraisal ratings were resolved via consensus. Singlesubject design studies were assessed using an adapted version of the Single Case Experimental Design (SCED) scale

(Tate et al., 2008) and group studies were assessed using

ASHAs critical appraisal scheme (Cherney, Patterson,

Raymer, Frymark, & Schooling, 2008; Mullen, 2007). See

Supplemental Materials Tables 1 and 2 for further information regarding the critical appraisal processes.

Interrater reliability associated with the sifting of titles

and abstracts as well as the critical appraisal process were

determined using Cohens kappa (; Cohen, 1988) and

weighted . Cohens was used in instances in which only

two rating options equal in weight were available for selection. Weighted was applied to critical appraisal items that

had hierarchical rating options (i.e., sampling process, random allocation, controlling for order effects, precision).

The following is Landis and Kochs (1977) scale for interpreting which was used to categorize the strength of the

agreement: poor agreement (<0.00), slight agreement

(0.000.20), fair agreement (0.210.40), moderate agreement (0.410.60), substantial agreement (0.610.80), and

almost perfect agreement (0.811.00). Percent agreement

was reported when could not be computed or when the

kappa value was zero.

For inclusion in this EBSR, studies had to be peerreviewed and experimental or quasi-experimental.

Furthermore, studies had to examine the impact of communication interventions on social communication skills of

children 36 months old or younger at-risk for or diagnosed

with ASD. For the purposes of this review, the ASD category

included the following diagnostic labels: Asperger syndrome, autism, autistic disorder, PDD, and pervasive development disordernot otherwise specified (PDD-NOS).

Accepted studies were written in English and published after

1970. Studies with mixed populations or mixed ages were

excluded unless data could be separated for analyses. In

addition, only participant data from single-subject design

studies that integrated a control mechanism (i.e., studies

with a withdrawal or reversal phase and/or multiple baseline

design studies) were included; consequently, multiple baseline design studies across participants without a withdrawal

or reversal phase which included only one participant who

met our age criterion were not accepted as they became an

AB design. Both single-subject and group design studies

were included as the former provides information about the

impact of an intervention in consideration of an individuals

unique abilities, whereas the latter are used to evaluate the

generalizability (i.e., external validity) of a treatments

effects.

Interventions in included studies were required to contain at a minimum a description of the training method(s) or

techniques from which they were comprised. Study findings were classified by social communication outcome categories (i.e., joint attention, social reciprocity, language and

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at Universitas Gadjah Mada on April 10, 2015

248

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 29(4)

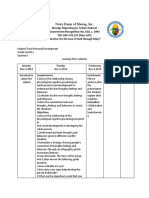

Table 1. Clinical Question 1: Prelinguistic-Joint Attention Findings.

Single-subject study outcomes

Single-subject studies

Group study outcomes

ES (NAP)

ES magnitude

p value

Group studies

Joint attention intervention

Jones, Carr, and Feeley (2006)

Krstovska-Guerrero and Jones

(2013)

Rocha, Schreibman, and

Stahmer (2007)

Joint attention-mediated learning

Schertz and Odom (2007)

Reciprocal imitation training

0.391.00

1.00

Mediumlarge

Large

NR

NR

Autism 1-2-3 project

Wong and Kwan (2010)

Brief Early Start Denver Model

0.720.97

Mediumlarge

NR

Rogers et al. (2012)

0.610.76

Ingersoll and Schreibman

(2006)

Simultaneous communication

Kouri (1988)

Social engagement intervention

Vernon, Koegel, Dauterman,

and Stolen (2012)

0.000.98

1.00

0.810.99

ES (d)

ES magnitude

p value

3.13

Large

.001

0.000.13 (2/3

CI:NS)

Small

NR

Hanens More than Wordsa

Carter et al. (2011)

0.80.24 (CI:NS)

Small

NR

Interpersonal synchrony vs. non

interpersonal synchrony

Medium

NR Landa, Holman, ONeill, and

0.420.89

Mediumlarge .08.41

Stuart (2011)

Joint attention-mediated learning

Large

p < .05 Schertz, Odom, Baggett, and

0.701.39

Large

1/3 NS

Sideris (2013)

Mediumlarge

NR

Smalllarge

NR

Note. ES = effect size; NAP = non-overlap of all pairs; CI = confidence interval; NR = not reported; NS = not significant.

a

Only treatment follow-up data (i.e., maintenance data) were reported in this study.

Table 2. Clinical Question 2: Prelinguistic-Social Reciprocity Findings.

Single-subject study outcomes

Single-subject studies

Joint attention-mediated learning

Schertz and Odom (2007)

Peer-mediated intervention

Goldstein, Kaczmarek, Pennington,

and Shafer (1992)

Simultaneous communication

Kouri (1988)

Social engagement intervention

Vernon, Koegel, Dauterman, and

Stolen (2012)

ES (NAP)

ES magnitude

p value

0.350.74

Medium

NR

0.220.57 Smallmedium

0.921.00

Large

0.940.98

Large

NR

Group study outcomes

Group studies

Autism 1-2-3 project

Wong and Kwan (2010)

Brief Early Start Denver Model

Rogers et al. (2012)

Joint attention-mediated learning

p < .05 Schertz, Odom, Baggett, and

Sideris (2013)

ES (d)

ES magnitude p value

NR

NR

0.07 (CI:NS)

Small

.008

NR

0.55

Medium

>.05

NR

Note. ES = effect size; NAP = non-overlap of all pairs; CI = confidence interval; NR = not reported; NS = not significant.

related cognitive skills, and behavioral and emotional regulation), and then further categorized into communication

developmental stages (i.e., prelinguistic, emerging language) using the framework devised by ASHA (2006). So,

examples of outcomes classification labels include prelinguistic-joint attention, prelinguistic-social reciprocity, and

emerging languagelanguage and related cognitive skills.

Key participant information (e.g., age), intervention variables (e.g., duration) and outcomes data (e.g., joint attention), including maintenance and generalization findings,

were extracted from each study. Given the importance of

the ecological validity of findings, qualitative data gathered

from surveys and observations completed by caregivers and

non-participating clinical professionals was extracted, if

reported, to evaluate social validity.

Statistical significance and effect size were reported if

available in the study or calculated if applicable raw data

were provided. For single-subject design studies, linear

graphs were visually analyzed to compute the non-overlap

of all pairs (NAP; Parker & Vannest, 2009) effect size for

intervention outcomes. Conventions for applying NAP,

including classification of the magnitude of the effect size

(i.e., small = 00.31, medium = 0.320.84, and large =

0.851.00), were adapted from Parker and Vannest (2009).

For group studies, the calculated effect size metric was

Cohens d (Cohen, 1988). For the purpose of assigning

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at Universitas Gadjah Mada on April 10, 2015

249

Morgan et al.

Table 3. Clinical Question 3: Prelinguistic-Language and Related Cognitive Skills Findings.

Single-subject study outcomes

Single-subject studies

ES (NAP)

ES magnitude

Group study outcomes

p value

Group studies

NR

Brief Early Start

Denver Model

Rogers et al. (2012)

Hanens More than

Words a

Carter et al. (2011) 0.15 to 0 (CI:NS)

Early Start Denver Model

Vismara, Colombi, and Rogers

(2009)

0.201.00

Smalllarge

Pivotal response training

Steiner, Gengoux, Klin, and

Chawarska (2013)

Reciprocal imitation training

Ingersoll and Schreibman (2006)

Reciprocal imitation training vs. video

modeling

Cardon and Wilcox (2011)

Simultaneous communication

Kouri (1988)

UCLA treatment model

Smith, Buch, and Gamby (2000)

Video modeling imitation training

Cardon (2012)

1.00

Large

NR

0.001.00

Smalllarge

NR

0.710.85 (RIT)

0.730.98 (VM)

Medium

Mediumlarge

NR

NR

0.831.00

Large

0.711.00

Mediumlarge

NR

0.931.00

Large

NR

ES (d)

ES magnitude p value

0.14 (CI:NS)

Small

NR

Small

NR

Note. ES = effect size; NAP = non-overlap of all pairs; RIT = reciprocal imitation training; VM = video modeling; M = mixture of statistically significant and non-statistically

significant findings; CI = confidence interval; NR = not reported; NS = not significant.

a

Only treatment follow-up data (i.e., maintenance data) were reported in this study.

descriptive labels to effect sizes reported in group studies,

the following modified version of Cohens classification of

effect size magnitude was used: small = 0 to 0.34; medium

= 0.35 to 0.64; and large = 0.65 or greater with positive

effect sizes favoring the intervention. When provided or

calculable, confidence intervals were also reported for

group study effect sizes. For both single-subject and group

studies, results were considered statistically significant if

the p value was less than .05. For group studies, effect size

confidence intervals that contained the null effect (i.e., d =

0) were not considered to be statistically significant. Both

effect sizes (and their confidence intervals when calculable)

and p values were reported because sample size has a

greater impact on p-value calculation than effect size computation (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009).

Therefore, a treatment effect may be present, but not appear

statistically significant based on the p value due to a sample

size that is too small to detect a treatment effect (i.e., the

study does not have enough power).

Results

Twenty-six studies (n = 19 single-subject and 7 group studies) from 1,379 identified citations were accepted for this

EBSR. The full list of excluded studies and reason(s) for

ineligibility (e.g., not population or age of interest) is available on request. Substantial interrater reliability ( = 0.69;

Cohen, 1988) was noted between the authors who sifted

abstracts and full-text articles. Kappa ratings for critical

appraisal items from both study designs ranged from slight

agreement ( = 0.13) to substantial agreement ( = 0.77),

whereas percent agreement ranged from 84% to 100%.

Most critical appraisal items were adequately addressed in

accepted single-subject design and group studies. See

Supplemental Materials Tables 1 and 2 for more information about study quality.

A total of 427 participants, who were aged 10 to 36 months

and diagnosed with autism, ASD, PDD-NOS, or Asperger

syndrome, were included in this EBSR. Participant race/ethnicity, which was reported in a few studies (Carter et al.,

2011; Dawson et al., 2010; Landa, Holman, ONeill, &

Stuart, 2011; Rogers et al., 2012; Vernon, Koegel, Dauterman,

& Stolen, 2012; Vismara, Colombi, & Rogers, 2009),

included American Indian, Alaskan Native, Asian, Black,

Hispanic or Latino, Multiracial, and White. See Supplemental

Materials Table 3 for additional participant and service delivery data as well as descriptions of interventions.

Study Outcomes

Included studies examined various social communication

outcomes across prelinguistic and emerging language developmental stages to address three of four a priori clinical questions. Study outcomes were classified as prelinguistic-joint

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at Universitas Gadjah Mada on April 10, 2015

250

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 29(4)

attention (Clinical Question 1; n = 11 studies), prelinguisticsocial reciprocity (Clinical Question 2; n = 7 studies), prelinguistic-language and related cognitive skills (Clinical

Question 3; n = 9 studies), and emerging languagelanguage

and related cognitive outcomes (Clinical Question 3; n = 18

studies). No outcomes in the accepted studies fell into the

behavior and emotional regulation category (Clinical

Question 4). For most clinical questions, conclusions about

the relationship between study quality and study outcomes

could not be drawn because study quality was similar across

studies. For Clinical Question 2, however, one of the singlesubject studies (Kouri, 1988) had larger treatment effects but

lower study quality than the other two single-subject studies

in this category (Goldstein, Kaczmarek, Pennington, &

Shafer, 1992; Schertz & Odom, 2007). As indicated in at least

one study of each of the four aforementioned outcome categories, caregivers overwhelmingly were satisfied with the

interventions and associated outcomes. Supplemental

Materials Table 4 provides a summary of findings across

social communication outcome goals and communication

developmental stages. Additional information about study

findings by communication developmental stage and social

communication categories is elucidated below.

Prelinguistic-joint attention findings.Table 1 provides a

detailed list of interventions and associated outcomes for

the 11 studies of prelinguistic-joint attention (Clinical Question 1). Findings from single-subject studies overwhelmingly indicated improvement in prelinguistic-joint attention

skills across the variety of treatment categories. The associated effect sizes ranged from small to large in magnitude

(NAP = 01.00), with the bulk being in the medium to large

range (NAP = 0.391.00). The greatest variability in treatment effect (NAP = 01.00) was noted across participants

who received various joint attention interventions (Jones,

Carr, & Feeley, 2006; Krstovska-Guerrero & Jones, 2013;

Rocha, Schreibman, & Stahmer, 2007; Schertz & Odom,

2007). No effect size confidence intervals were provided or

calculable and no p values were reported. All studies except

Kouri (1988) reported maintenance and generalization findings; overall, target behaviors were maintained following

treatment and skills were demonstrated across a variety of

people and settings.

Group study effect sizes were mainly medium to large in

magnitude (d = 3.13 to 1.39), with the exception of the findings associated with the Brief Early Start Denver Model (d =

00.13: Rogers et al., 2012). In most instances, the findings

were not statistically significant. However, in the case of

Wong and Kwan (2010), the treatment effect associated with

the Autism 1-2-3 Project intervention was in favor of the control group. Growth rate difference effect sizes were medium

to large for a comparison of interpersonal synchrony and

non-interpersonal synchrony interventions (Landa et al.,

2011); yet, they were accompanied by non-statistically

significant p values. In addition, within-group findings

revealed gains from pre- to post-test only for the intervention

group (Landa et al., 2011). The majority of maintenance findings as reported in studies of Hanens More than Words

(Carter et al., 2011) and a joint attention-mediated learning

(Schertz, Odom, Baggett, & Sideris, 2013) intervention were

small to large in magnitude (d = 0.081.18) and accompanied

by primarily non-statistically significant p values; the largest

effect sizes were associated with the joint attention intervention. Maintenance findings from the Landa et al. (2011) comparative study revealed large effect sizes (d = 0.811.56) at

post-treatment and medium to large effect sizes (d = 0.41

0.68) for growth rate differences between the groups; p values were not statistically different for the post-treatment or

growth rate difference data. No generalization findings were

reported.

Prelinguistic-social reciprocity findings.Findings from singlesubject studies that addressed prelinguistic-social reciprocity

outcomes (Clinical Question 2; see Table 2) were small to

large in effect size magnitude (NAP = 0.221.00), with findings from the simultaneous communication (Kouri, 1988)

and social engagement (Vernon et al., 2012) interventions

falling solely in the large range (i.e., NAP = 0.921.00). No p

value or effect size confidence interval information was

reported. Maintenance and generalization of prelinguisticsocial reciprocity findings were limited to a study of a joint

attention-mediated learning (Schertz & Odom, 2007) intervention. Findings revealed that the skills were maintained at

levels higher than what was seen during baseline and that

generalization occurred across a variety of settings.

Much variability existed in group study findings (see

Table 2), with a significant p value (p = .008) associated with

the Autism 1-2-3 Project intervention (Wong & Kwan, 2010),

a negligible effect size (d = 0.07) accompanied by a confidence interval containing the null effect reported in the study

of Brief Early Start Denver Model (Rogers et al., 2012), and

a medium (d = 0.55), but not statistically significant finding

from a joint attention-mediated learning intervention (Schertz

et al., 2013). A small (d = 0.10) and non-statistically significant maintenance finding was reported in Schertz et al.

(2013). No generalization findings were reported.

Prelinguistic-language and related cognitive skills findings.Table

3 provides a detailed list of interventions and associated outcomes in the prelinguistic-language and related cognitive

skills category (Clinical Question 3). The effect sizes from

single-subject studies were in the small to large range (NAP

= 01.00), with most falling in the medium to large range for

the following interventions: pivotal response training

(Steiner, Gengoux, Klin, & Chawarska, 2013), video modeling imitation training (Cardon, 2012), University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) treatment model (Smith, Buch, &

Gamby, 2000), and simultaneous communication (Kouri,

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at Universitas Gadjah Mada on April 10, 2015

251

Morgan et al.

Table 4. Clinical Question 3: Emerging LanguageLanguage and Related Cognitive Skills Findings.

Single-subject study outcomes

Single-subject studies

Behavioral intervention

Williams, PrezGonzlez, and Vogt

(2003)

Developmental, social

pragmatic intervention

Ingersoll, Dvortcsak,

Whalen, and Sikora

(2005)

Discrete trial training vs.

mand training

Jennett, Harris, and

Delmolino (2008)

Group study outcomes

ES (NAP)

ES magnitude

p value

1.00

Large

NR

0.710.86

Mediumlarge

NR

Early Start Denver

Model

Dawson et al. (2010)

0.941.00 (DTI)

Large

NR

1.00 (MT)

Large

NR

0.201.00

Smalllarge

NR

0.760.87

Mediumlarge

NR

Peer-mediated intervention

Goldstein, Kaczmarek,

Pennington, and Shafer

(1992)

Pivotal response training vs.

discrete trial training

Schreibman, Stahmer,

Cestone Barlett, and

Dufek (2009)

Reciprocal imitation

training

Ingersoll and Schreibman

(2006)

Simultaneous

communication

Kouri (1988)

Social engagement

intervention

Vernon, Koegel,

Dauterman, and Stolen

(2012)

Teaching strategy

intervention

Kashinath, Woods, and

Goldstein (2006)

UCLA treatment model

Smith, Buch, and Gamby

(2000)

0.240.61

Smallmedium

Autism 1-2-3 Project

Wong and Kwan

(2010)

Brief Early Start Denver

Model

Rogers et al. (2012)

Early Start Denver Model

Vismara, Colombi, and

Rogers (2009)

Enhanced milieu teaching

Kaiser, Hancock, and

Nietfeld (2000)

Group studies

Eclectic intervention

vs. applied behavioral

analysis

Zachor and Itzchak

(2010)

Hanens More than

Wordsa

Carter et al. (2011)

Interpersonal vs.

non-interpersonal

synchrony

Landa, Holman,

ONeill, and Stuart

(2011)

ES (d)

ES magnitude

p value

NR

NR

.01.04

0.24 to 0.24 (CI:NS)

Small

NR

0.580.66 (CI: 2/4 NS)

Mediumlarge .03.06

0.18 to 0.59 (CI: 3/4 NS) Smallmedium

NR

0.26 to 0.42 (CI:NS)

Smallmedium

NR

0.49

Medium

.18

NR

0.470.97

0.28 to 0.59

Mediumlarge

Smallmedium

NR

NR

0.000.86

Smalllarge

NR

0.001.00

Smalllarge

0.810.94

Mediumlarge

NR

0.480.96

Mediumlarge

NR

0.001.00

Smalllarge

NR

Note. ES = effect size; NAP = non-overlap of all pairs; NR = not reported; DTI = discrete trial instruction; MT = mand training; M = mixture of

statistically significant and non-statistically significant findings; CI = confidence interval; NS = not significant.

a

Only treatment follow-up data (i.e., maintenance data) were reported in this study.

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at Universitas Gadjah Mada on April 10, 2015

252

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 29(4)

1988). However, no effect size confidence intervals or p

value data were provided. Effect sizes from a comparative

study (Cardon & Wilcox, 2011) of reciprocal imitation and

video modeling were in the medium range (NAP = 0.71

0.85) with the exception of one finding for video modeling

which was large (NAP = 0.98); no p values or effect size

confidence intervals were reported. Maintenance and generalization findings were quite variable among the studies that

reported those data (Cardon, 2012; Cardon & Wilcox, 2011;

Ingersoll & Schreibman, 2006).

In regard to group studies, the Brief Early Start Denver

Model had a negligible post-treatment effect (d = 0.14)

that was associated with a confidence interval that contained the null effect (Rogers et al., 2012). Maintenance

findings, provided in a study of Hanens More than Words

(Carter et al., 2011), were negligible (i.e., d = 0) and accompanied by a confidence interval that contained the null

effect. No generalization findings were reported.

Emerging languagelanguage and related cognitive skills findings.

The majority of studies (n = 18) examined interventions that

addressed emerging languagelanguage and related cognitive skills (see Table 4 for a list of interventions and associated outcomes). Findings from single-subject studies were

in the small to large magnitude range (NAP = 01.00), with

effect sizes from the following studies falling in the medium

to large range: developmental, social pragmatic intervention (Ingersoll, Dvortcsak, Whalen, & Sikora, 2005); treatment strategy intervention (Kashinath, Woods, & Goldstein,

2006); behavioral intervention (Williams, Prez-Gonzlez,

& Vogt, 2003); and enhanced milieu teaching (Kaiser, Hancock, & Nietfeld, 2000). No p values or effect size confidence intervals were reported. Effect sizes from a

comparative study (Jennett, Harris, & Delmolino, 2008) of

discrete trial training and mand training were large (NAP =

0.941.00). In another comparative study (Schreibman,

Stahmer, Cestone Barlett, & Dufek, 2009), effect sizes for

the pivotal response training were medium to large (NAP =

0.470.97), whereas those for discrete trial training were

small to medium (NAP = 0.28 to 0.59). No p values or

effect size confidence intervals were reported in either comparative study. There was notable variability in maintenance

and generalization findings in the four studies (Ingersoll et

al., 2005; Ingersoll & Schreibman, 2006; Kaiser et al.,

2000; Vernon et al., 2012) that reported those data.

The effect sizes from group studies spanned from small

to large in magnitude (d = 0.24 to 0.66). Most findings

were not statistically significant with the exception of some

or all from the Autism 1-2-3 Project study (Wong & Kwan,

2010) and the Early Start Denver Model study (Dawson et

al., 2010). Effect sizes from comparative studies of an

eclectic intervention versus an applied behavioral analysis

intervention (Zachor & Itzchak, 2010) and an interpersonal

synchrony versus non-interpersonal synchrony intervention

(Landa et al., 2011) were small to medium in magnitude and

not statistically significant. All statistically significant

within-group pre- to post-test gains as well as gain scores

between groups were in favor of the intervention group

(Landa et al., 2011). Growth rate effect size was small (d =

0.09) and not statistically significant (p = .83; Landa et al.,

2011). Maintenance findings from a study of Hanens More

than Words (Carter et al., 2011) were small to medium in

magnitude (d = 0.16 to 0.42) and accompanied by confidence intervals that contained the null effect. In Landa and

colleagues (2011) comparative study, the maintenance

effect size was medium in magnitude (d = 0.57) and accompanied by a non-statistically significant p value (p = .24),

whereas the growth rate data collected during the maintenance period translated into a small effect size (d = 0.09)

and non-statistically significant p value (p = .83). No generalization findings were reported.

Discussion

This review of 26 intervention studies including 427 toddlers with ASD and spanning across a broad range of intervention categories indicated primarily positive treatment

effects on social communication skills in terms of both

growth rates and gain scores for all outcome categories for

which social communication data were available, with the

exception of emerging languagelanguage and related cognitive skills, which showed variable and mixed results.

Maintenance results were also variable across all outcome

categories and reporting of generalization results was limited. As a whole, caregivers were satisfied with the interventions and their associated outcomes.

The overall body of literature included in this review

was of appropriate scientific rigor with 24 of the 26 studies

sufficiently meeting the majority of the critical appraisal

points. Yet, patterns of weakness in research design were

noted for both single-subject design (e.g., assessors were

not blind to treatment) and group studies (e.g., use of convenience sampling). Despite these areas of weakness, no

distinct patterns were detected between study quality indicators and reporting of outcomes with the exception of the

Kouri (1988) study. Although the Kouri study reported

large effects for the three prelinguistic outcome areas, this

study met only 4 of the 12 quality indicator appraisal items.

Given potential weaknesses in the design of this particular

study, it is possible that effect sizes for this study could be

inflated and should be interpreted with caution. Following

is a discussion of treatment effects on social communication

within the context of study design.

Single-Subject Designs

Single-subject intervention studies targeting social communication outcomes for toddlers with ASD generally reported

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at Universitas Gadjah Mada on April 10, 2015

253

Morgan et al.

improvements across outcome categories. Medium to large

effects were present for the bulk of studies reporting outcomes for the three prelinguistic outcome categories. For

the joint attention outcomes, the largest variability in effects

was reported for the interventions in the joint attention category. Variability in improvement was reported for the

emerging languagelanguage and related cognitive skills

category as evidenced by effects that ranged from small to

large. For the proportion of studies that reported maintenance and generalization findings, outcomes were highly

variable.

Group Designs

The seven group design studies included in this review

showed positive trends in growth with respect to social

communication outcomes and a range of effect sizes were

reported; however, very few results indicated statistical significance. In summarizing the social communication outcomes reported for group studies, the most promising

effects appear to be in favor of clinician-implemented interventions providing the greatest intensity (Dawson et al.,

2010; Landa et al., 2011). Schertz and colleagues (2013)

provided the single exception to this by reporting on a parent-implemented intervention of brief duration and intensity having an effect on joint attention as well as an effect on

emerging language and related cognitive skills in favor of

the treatment group. Because this particular study, however,

did not blind assessors to the treatment condition, the findings may be biased and must be viewed with caution.

Overarching Implications of Findings

Both focused interventions, which are directed toward

improving targeted symptoms or needs of the child with

ASD, and comprehensive interventions, which are developed to broadly reduce autism symptoms and improve

overall functioning, have been used to improve social communication functioning in children with ASD. Singlesubject design studies included in this review were typically

associated with positive changes in social communication

outcomes, whereas interventions assessed within-group

studies mainly resulted in mixed findings. However, a summary of findings relative to our research questions across

study designs indicates a preponderance of promising

effects for prelinguistic-joint attention and social reciprocity outcomes, with the bulk of interventions associated with

moderate to large treatment effects. With respect to language and related cognitive outcomes at both the prelinguistic and emerging language stages, an inconsistent

picture emerges given the broad range of treatment effects

reported. Finally, the studies reviewed provided no indication of effects on behavioral and emotional regulation outcomes. Although the positive results reported for social

communication outcomes for toddlers with ASD are

encouraging, the mixed nature of these results raises concerns with respect to the focus of treatment outcomes, treatment intensity, and agent of delivery (e.g., clinician versus

parent-mediated), as well as the types of measures utilized

to document intervention outcomes.

Focus of Treatment

The application of a developmental framework ensures that

prelinguistic-social communication skills are addressed

prior to symbolic language (ASHA, 2006; NRC, 2001;

Prizant, Wetherby, Rubin, & Laurent, 2003). In stark contrast to that developmental emphasis is the finding that the

majority of studies in this EBSR were focused on emerging

languagelanguage and related cognitive skills. With relatively few studies evaluating the effects of earlier-emerging,

foundational social communication skills, such as joint

attention and social reciprocity, we question whether normal developmental trajectories are being overlooked in the

bulk of toddler interventions for ASD. Because longitudinal

research has shown clearly the link between early social

communication skills such as joint attention and long-term

linguistic outcomes such as initiating bids and sharing emotions (Wetherby, Watt, Morgan, & Shumway, 2007) a stronger impetus for selecting outcome goals related to the core

challenges of ASD seems warranted. Of additional concern

is the fact that no studies reported behavior and emotional

regulation findings. It may be that these collective skills

have not been targeted due to challenges with measurement

or other practical reasons.

Intensity

Although several systematic review panels have recommended active engagement in intensive instruction for a

minimum of 5 hr per day (Maglione, Gans, Das, Timbie, &

Kasari, 2012; NRC, 2001), none of the included studies in

this review evaluated intensity of instruction to that extent.

One study, however, did report an average of 20 hr per week

(Dawson et al., 2010). Although the findings of this EBSR

suggest that fewer hours of treatment may be sufficient to

ameliorate social communication deficits and support

growth in social communication skills, it is unclear what the

critical mass is for maximizing long-term outcomes for

children with ASD.

That the most promising effects on social communication

outcomes appear to be in favor of clinician-implemented

interventions providing the greatest intensity (Dawson et al.,

2010; Landa et al., 2011), raises concerns for future research.

First, it is important to determine whether comparable treatment effects can be achieved with reduced professional time

since practical, sustainable application in community settings may be compromised due to limited access to and the

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at Universitas Gadjah Mada on April 10, 2015

254

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 29(4)

high costs of qualified and trained professionals. Second,

while current studies highlight potential limitations of parent-mediated approaches, these interventions have greater

longevity given the number of hours a child spends with his

or her parents versus clinicians both in these early stages and

beyond (Woods & Brown, 2011). Thus, it is important to

evaluate innovative ways to maximize dosage and intensity

of parent-implemented interventions and to incorporate

strategies for accurate measurement of the intensity with

which parents implement intervention techniques during

everyday activities.

Agent of Delivery and Setting

The majority of studies included in this review described

delivery of treatment as a shared effort between the professional and the caregiver, with interventions being carried

out in clinical, classroom, and home settings. Several studies did not clearly indicate these methodological details.

Given that purely parent-implemented studies have not

reported significant effects on child social communication

outcomes, it is critical for parent-implemented interventions to be evaluated while controlling for density of parent

implementation, including measures of treatment fidelity

and evaluation of parent learning.

As a result of the documented challenges with generalization of learning for children with ASD, natural environments have been recommended as preferred intervention

contexts. Because treatment provided by caregivers in a

natural environment could be utilized to address issues

related to dosage and intensity, future research should

address the relative effects of providing intervention in natural versus more clinically oriented settings. Related to

issues of context and whether caregivers or professionals

are delivering the treatment is that new skill maintenance

and generalization in natural contexts should be carefully

evaluated. Only a handful of studies reported evaluating

generalization and maintenance, and those findings were

not assessed across a variety of contexts and/or communication partners, with the exception of the KrstovskaGuerrero and Jones (2013) study which evaluated

generalization across communication partners (i.e., interventionist and caregiver) and with novel materials.

Measurement

The challenge of comparing results across study designs

was further compounded by types of outcome measures

administered. Proximal measures were typically used in

single-subject designs to detect specific, incremental

changes in target behaviors (e.g., frequency of parentchild

interactions; Green et al., 2010) that directly correspond to

what was addressed in treatment via direct observations,

whereas distal measures, assessments used to ascertain the

transfer of change from intervention targets, were often

used in group designs (e.g., Vineland Adaptive Behavior

Scales [VABS]; Sparrow, Cicchetti, & Balla, 2005).

Differences in the degree of sensitivity of the two outcome

measures varies depending on the type of outcome (i.e.,

proximal or distal) measured. In concert, these findings

warrant more single-subject and group design studies that

include a combination of proximal and distal measures of

outcome.

Limitations of This EBSR

This EBSR has two primary limitations that are worthy of

note. To ensure that experts in the field vetted study quality,

only peer-reviewed research was accepted in this EBSR.

However, since the likelihood of publishing studies with

significant findings is higher than the likelihood of publishing studies with non-statistically significant results, the risk

of publication bias is high. Only studies written in English

were accepted, which limited the scope of the search for

relevant articles for this EBSR. As is the case with only

accepting peer-reviewed studies, studies on this topic written in other languages could provide another dimension to

the understanding of this topic and/or may contain results

that are principally contrary to the findings in this EBSR.

Conclusion

Although the mixed results described above prevent definitive statements about the efficacy of social communication

interventions for the infant and toddler population with

ASD, the positive findings from this review and previous

reviews (e.g., NRC, 2001; Schertz et al., 2012) suggest benefit from interventions focusing on social communication.

Limited research for this population is available with

respect to some of the specific intervention domains identified as critical by the ASHA (2006) guideline that addresses

diagnosis, assessment, and intervention of difficulties associated with ASD across the life span. As longitudinal

research provides additional evidence as to long-term outcomes associated with acquisition of early social communication skills, a stronger emphasis on outcome goals related

to the core challenges of ASD in prelinguistic-social communication may be revealed. Interventions that have the

potential to be implemented by early intervention systems

that address multiple outcomes and can provide a strong

family component designed to maximize child active

engagement are identified as critical priorities for the next

phase of intervention research.

Authors Note

This systematic review was conducted under the auspices of the

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association; however, this

is not an official position statement of the Association.

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at Universitas Gadjah Mada on April 10, 2015

255

Morgan et al.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest

with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this

article: Three of the authors are salaried employees of the

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, the organization through which this systematic review was completed.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research,

authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Materials Tables 14 are available at focus.sagepub.

com/supplemental.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in

the systematic review.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2006).

Guidelines for speech-language pathologists in diagnosis,

assessment, and intervention of autism spectrum disorders

across the life span (Guidelines). Retrieved from www.asha.

org/policy

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H.

R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. West Sussex, UK:

John Wiley.

*Cardon, T. A. (2012). Teaching caregivers to implement video

modeling imitation training via iPad for their children with

autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 13891400.

*Cardon, T. A., & Wilcox, M. J. (2011). Promoting imitation in

young children with autism: A comparison of reciprocal imitation training and video modeling. Journal of Autism and

Developmental Disorders, 41, 654666.

*Carter, A. S., Messinger, D. S., Stone, W. L., Celimli, S.,

Nahmias, A. S., & Yoder, P. (2011). A randomized controlled trial of Hanens more than words in toddlers with

early autism symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and

Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 52, 741752.

Cherney, L. R., Patterson, J. P., Raymer, A., Frymark, T., &

Schooling, T. (2008). Evidence-based systematic review:

Effects of intensity of treatment and constraint-induced language therapy for individuals with stroke-induced aphasia.

Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51,

12821299.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

*Dawson, G., Rogers, S., Munson, J., Smith, M., Winter, J.,

Greenson, J., . . .Varley, J. (2010). Randomized, controlled

trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: The Early

Start Denver Model. Pediatrics, 125, e17e23.

Dollaghan, C. A. (2007). The handbook for evidence-based practice in communication disorders. Baltimore, MD: Paul H.

Brookes.

*Goldstein, H., Kaczmarek, L., Pennington, R., & Shafer, K.

(1992). Peer-mediated intervention: Attending to, commenting on, and acknowledging the behavior of preschoolers with

autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 25, 289305.

Green, J., Charman, T., McConachie, H., Aldred, C., Slonims, V.,

Howlin, P., . . . PACT Consortium. (2010). Parent-mediated

communication-focused intervention in children with autism

(PACT): A randomized controlled trial. The Lancet, 375,

21522160.

*Ingersoll, B., Dvortcsak, A., Whalen, C., & Sikora, D. (2005).

The effects of a developmental, social-pragmatic language

intervention on rate of expressive language production in

young children with autistic spectrum disorders. Focus on

Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 20, 213222.

*Ingersoll, B., & Schreibman, L. (2006). Teaching reciprocal imitation skills to young children with autism using a naturalistic behavioral approach: Effects on language, pretend play,

and joint attention. Journal of Autism and Developmental

Disorders, 36, 487505.

*Jennett, H. K., Harris, S. L., & Delmolino, L. (2008). Discrete

trial instruction vs. mand training for teaching children with

autism to make requests. Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 24,

6985.

*Jones, E. A., Carr, E. G., & Feeley, K. M. (2006). Multiple

effects of joint attention intervention for children with autism.

Behavior Modification, 30, 782834.

*Kaiser, A. P., Hancock, T. B., & Nietfeld, J. P. (2000). The

effects of parent-implemented Enhanced Milieu Teaching on

the social communication of children who have autism. Early

Education and Development, 11, 423446.

*Kashinath, S., Woods, J., & Goldstein, H. (2006). Enhancing

generalized teaching strategy use in daily routines by parents

of children with autism. Journal of Speech, Language, and

Hearing Research, 49, 466485.

*Kouri, T. A. (1988). Effects of simultaneous communication

in a child-directed intervention approach with preschoolers with severe disabilities. Augmentative and Alternative

Communication, 4, 222232.

*Krstovska-Guerrero, I., & Jones, E. A. (2013). Joint attention in

autism: Teaching smiling coordinated with gaze to respond to

joint attention bids. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders,

7, 93108.

*Landa, R. J., Holman, K. C., ONeill, A. H., & Stuart, E. A. (2011).

Intervention targeting development of socially synchronous

engagement in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder: A

randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and

Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 52, 1321.

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer

agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33, 159174.

Maglione, M., Gans, D., Das, L., Timbie, J., & Kasari, C.

(2012). Nonmedical interventions for children with ASD:

Recommended guidelines and further research needs.

Pediatrics, 130, S169S178.

Mullen, R. (2007, March 6). The state of the evidence: ASHA

develops levels of evidence for communication sciences and

disorders. The ASHA Leader, 12(3), 89, 2425.

National Research Council. (2001). Educating children with

autism (Committee on Educational Interventions for Children

with Autism, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and

Education). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Parker, R. I., & Vannest, K. (2009). An improved effect size

for single-case research: Nonoverlap of all pairs. Behavior

Therapy, 40, 357367.

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at Universitas Gadjah Mada on April 10, 2015

256

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 29(4)

Prizant, B. M., Wetherby, A. M., Rubin, E., & Laurent, A. C.

(2003). The SCERTS model: A transactional, family-centered

approach to enhancing communication and socioemotional

abilities of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of

Infants and Young Children, 16, 296316.

*Rocha, M. L., Schreibman, L., & Stahmer, A. (2007). Effectiveness

of training parents to teach joint attention in children with

autism. Journal of Early Intervention, 29, 154172.

*Rogers, S. J., Estes, A., Lord, C., Vismara, L., Winter, J.,

Ftizpatrick, A., & Dawson, G. (2012). Effects of a Brief Early

Start Denver Model (ESDM)Based parent intervention on

toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorders: A randomized

controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child &

Adolescent Psychiatry, 51, 10521065.

*Schertz, H. H., & Odom, S. L. (2007). Promoting joint attention

in toddlers with autism: A parent-mediated developmental

model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37,

15621575.

*Schertz, H. H., Odom, S. L., Baggett, K. M., & Sideris, J. H.

(2013). Effects of Joint Attention Mediated Learning for toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: An initial randomized

controlled study. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28,

249258.

Schertz, H. H., Reichow, B., Tan, P., Vaiouli, P., & Yildirim, E.

(2012). Interventions for toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: An evaluation of research evidence. Journal of Early

Intervention, 34, 166189.

*Schreibman, L., Stahmer, A. C., Cestone Barlett, V., & Dufek,

S. (2009). Brief report: Toward refinement of a predictive

behavioral profile for intervention outcome in children with

autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3, 163172.

*Smith, T., Buch, G. A., & Gamby, T. E. (2000). Parent-directed,

intensive early intervention for children with pervasive developmental disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities,

21, 297309.

Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V., & Balla, D. A. (2005). Vineland

Adaptive Behavior Scales (2nd ed.). Circle Pines, MN:

American Guidance Service.

*Steiner, A. M., Gengoux, G. W., Klin, A., & Chawarska, K.

(2013). Pivotal response treatment for infants at-risk for

autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. Journal of Autism

and Developmental Disorders, 43, 91102.

Tate, R., McDonald, S., Perdices, M., Togher, L., Schultz, R., &

Savage, S. (2008). Rating the methodological quality of singlesubject designs and n-of-1 trials: Introducing the Single Case

Experimental Design (SCED) Scale. Neuropsychological

Rehabilitation, 18(4), 385401.

*Vernon, T. W., Koegel, R. L., Dauterman, H., & Stolen, K.

(2012). An early social engagement intervention for young

children with autism and their parents. Journal of Autism and

Developmental Disorders, 42, 27022717.

*Vismara, L. A., Colombi, C., & Rogers, S. J. (2009). Can one

hour per week of therapy lead to lasting changes in young

children with autism? Autism, 13, 93115.

Wallace, K. S., & Rogers, S. J. (2010). Intervening in infancy:

Implications for autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child

Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 13001320.

Wetherby, A. M., Watt, N., Morgan, L., & Shumway, S. (2007).

Social communication profiles of children with autism spectrum disorders in the second year of life. Journal of Autism

and Developmental Disorders, 37, 960975.

*Williams, G., Perez-Gonzalez, L. A., & Vogt, K. (2003). The

role of specific consequences in the maintenance of three

types of questions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36,

285296.

*Wong, V. C. N., & Kwan, Q. K. (2010). Randomized controlled

trial for early intervention for autism: A pilot study of the

Autism 1-2-3 Project. Journal of Autism and Developmental

Disorders, 40, 677688.

Woods, J., & Brown, J. (2011). Integrating family capacitybuilding and child outcomes to support social communication

development in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Topics in Language Disorders, 31, 235246.

*Zachor, D. A., & Itzchak, E. B. (2010). Intervention approach,

autism severity and intervention outcomes in young children.

Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 425432.

Downloaded from foa.sagepub.com at Universitas Gadjah Mada on April 10, 2015

También podría gustarte

- Career Opportunity: PT Integra Karya SentosaDocumento1 páginaCareer Opportunity: PT Integra Karya SentosaFrontier JuniorAún no hay calificaciones

- Stress Among Mothers of Children WithDocumento12 páginasStress Among Mothers of Children WithFrontier JuniorAún no hay calificaciones

- Hill 2009Documento12 páginasHill 2009Frontier JuniorAún no hay calificaciones

- MRDocumento73 páginasMRFrontier JuniorAún no hay calificaciones

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDe EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)De EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Calificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDe EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDe EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDe EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDe EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDe EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDe EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDe EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDe EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDe EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDe EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDe EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDe EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDe EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDe EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDe EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyCalificación: 3.5 de 5 estrellas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDe EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)De EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Calificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (121)

- The Perks of Being a WallflowerDe EverandThe Perks of Being a WallflowerCalificación: 4.5 de 5 estrellas4.5/5 (2104)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDe EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (821)

- (IIEF) : Patient QuestionnaireDocumento3 páginas(IIEF) : Patient Questionnairerag manduaruwrAún no hay calificaciones

- PETA1 TopicPoolDocumento6 páginasPETA1 TopicPoolRich BlancaflorAún no hay calificaciones

- Reinforcement TheoryDocumento3 páginasReinforcement TheoryFenil PanchalAún no hay calificaciones

- Midterm Exams Theories of Crime 3Documento4 páginasMidterm Exams Theories of Crime 3maynard pascualAún no hay calificaciones

- A Survey of The Perception of Students On The Study of Sex Education in Secondary School Social Studies in Dekina Local Government Area of Kogi State1Documento8 páginasA Survey of The Perception of Students On The Study of Sex Education in Secondary School Social Studies in Dekina Local Government Area of Kogi State1Israh GonzalesAún no hay calificaciones

- Models of Strategic Human Resource ManagementDocumento40 páginasModels of Strategic Human Resource ManagementErin Thorpe100% (2)

- Code of EthicsDocumento1 páginaCode of EthicsJoshua R. CruzAún no hay calificaciones

- The Gateway Experience®: Wave V ExploringDocumento4 páginasThe Gateway Experience®: Wave V ExploringEvan SchowAún no hay calificaciones

- BANNISTER, Jon FYFE, Nick. Introduction. Fear and The CityDocumento7 páginasBANNISTER, Jon FYFE, Nick. Introduction. Fear and The CityCarol ColombaroliAún no hay calificaciones

- Aera, Apa & Ncme, 2014 PDFDocumento241 páginasAera, Apa & Ncme, 2014 PDFMacarena Yunge100% (2)

- Module 1 Concept of Growth and DevelopmentDocumento34 páginasModule 1 Concept of Growth and DevelopmentElvis Quitalig100% (1)

- EDUC-5420 - Week 1# Written AssignmentDocumento7 páginasEDUC-5420 - Week 1# Written AssignmentShivaniAún no hay calificaciones

- CB-M2 Quiz 2 1Documento1 páginaCB-M2 Quiz 2 1ramesh kumarAún no hay calificaciones

- AssertivenessDocumento97 páginasAssertivenessHemantAún no hay calificaciones

- REFLECTION PAPER 21st CENTURY LITERATUREDocumento1 páginaREFLECTION PAPER 21st CENTURY LITERATUREdumapiasbernalyn02Aún no hay calificaciones

- LPC Personal DevelopmentDocumento3 páginasLPC Personal DevelopmentThelma LanadoAún no hay calificaciones

- Janina Fisher DISSOCIATIVE PHENOMENA IN THE EVERYDAY LIVES OF TRAUMA SURVIVORSDocumento38 páginasJanina Fisher DISSOCIATIVE PHENOMENA IN THE EVERYDAY LIVES OF TRAUMA SURVIVORSMargaret KelomeesAún no hay calificaciones

- Instagram Fitspiration PDFDocumento15 páginasInstagram Fitspiration PDFIsabella LozanoAún no hay calificaciones

- Visual Supports HDocumento2 páginasVisual Supports Hapi-241345040100% (1)

- O&MFINALDocumento3 páginasO&MFINALVictoria Quebral CarumbaAún no hay calificaciones

- Case Study On BullyingDocumento31 páginasCase Study On BullyingKausar Omar50% (2)

- Astin (1993)Documento3 páginasAstin (1993)Kh TAún no hay calificaciones

- Conclusion and RecommendationDocumento1 páginaConclusion and RecommendationDevorah Jeanne RamosAún no hay calificaciones

- Occupational Stress & OD-Module 6 MBADocumento23 páginasOccupational Stress & OD-Module 6 MBAAakash KrAún no hay calificaciones

- Concept Map Diagnosis and InterventionsDocumento3 páginasConcept Map Diagnosis and Interventionsmenickel3Aún no hay calificaciones

- GATTACA Student's WorksheetDocumento3 páginasGATTACA Student's WorksheetAngel Angeleri-priftis.Aún no hay calificaciones

- IB Psychology Chapter 02 Learning ObjectivesDocumento13 páginasIB Psychology Chapter 02 Learning ObjectivesAndrea BadilloAún no hay calificaciones

- Parents On Your Side:: by Faiza Rais and Bisma UroojDocumento11 páginasParents On Your Side:: by Faiza Rais and Bisma UroojBismaUroojAún no hay calificaciones

- Week 1 Introduction To Technopreneurial ManagementDocumento21 páginasWeek 1 Introduction To Technopreneurial ManagementTadiwanashe MagombeAún no hay calificaciones

- Personal Development g12Documento54 páginasPersonal Development g12Celina LimAún no hay calificaciones