Documentos de Académico

Documentos de Profesional

Documentos de Cultura

Dismissal of Lawsuit Regarding Apple MacBook Logic Boards

Cargado por

Mikey CampbellDerechos de autor

Formatos disponibles

Compartir este documento

Compartir o incrustar documentos

¿Le pareció útil este documento?

¿Este contenido es inapropiado?

Denunciar este documentoCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

Dismissal of Lawsuit Regarding Apple MacBook Logic Boards

Cargado por

Mikey CampbellCopyright:

Formatos disponibles

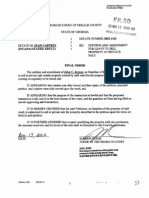

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page1 of 16

1

2

3

4

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

5

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

6

7

8

9

URIEL MARCUS and BENEDICT

VERCELES, on behalf of others similarly

situated,

11

For the Northern District of California

United States District Court

10

12

13

No. C 14-03824 WHA

Plaintiffs,

v.

ORDER GRANTING MOTION

TO DISMISS

APPLE INC,

Defendant.

/

14

15

INTRODUCTION

16

In this putative product-defect class action, defendant moves to dismiss under FRCP

17

12(b)(6). For the following reasons, defendants motion is GRANTED.

18

19

STATEMENT

In May 2014, plaintiffs Uriel Marcus and Benedict Verceles filed this putative class action

20

complaint against defendant Apple Inc. in the Southern District of Texas on behalf of all persons

21

who purchased certain Apple MacBook laptop computers in the United States between May 20,

22

2010 and the present. In July 2014, Apple filed a motion to dismiss and a motion to change venue

23

to the Northern District of California. Apples motion to change venue was unopposed, and the

24

action was transferred to this district. Apple then re-noticed and re-filed its motion to dismiss (Dkt.

25

Nos. 78, 2021, 2526, 30).

26

The complaint contains the following factual allegations. Apple allegedly sold MacBook

27

laptop computers containing defective logic boards that routinely failed within two years of

28

purchase. Failure of the component logic board, which houses the computers integrated circuits

and processors, rendered the computer useless. The complaint alleges that the logic board defect

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page2 of 16

was the result of negligent design, production, and testing, that Apple was aware of the defect for

over six years, failed to notify consumers, and that Apple continues to market and sell the

defective logic boards.

4

5

boards but did not act, and that Apple subsequently willfully and intentionally concealed

knowledge of the defect (Compl. 3). The complaint also alleges that Apple was aware of the

defective logic boards by virtue of complaints within customer reviews posted to the Apple

Online Store. The complaint excerpts 27 of these reviews. Nevertheless, Apple continues to sell

them.

For the Northern District of California

10

United States District Court

Plaintiffs further allege that in 2011, Apple CEO Tim Cook was told of the defective logic

Plaintiffs aver that Apple markets the reliability and functionality of the logic board for

11

its MacBook computers. The complaint puts forth four alleged representations made by Apple

12

regarding the laptop computers (Compl. 2, 17, 18, 19):

13

Regarding the Macbook Pro series laptop computers, Apple makes

the following representations: State of the Art, Breakthrough,

Easy Access to Connections and Ports.

14

15

Regarding the MacBook series laptop computers, Apple makes the

following representations: The new MacBook is faster, has even

more memory and storage, and is an ideal notebook for customers

growing library of digital music, photos and movies.

16

17

Apple also boasts that its MacBook Pro is its state of the art

flagship portable designed for mobile professionals and life on

the road.

18

19

The MacBook Pro and Macbook were represented as being, The

worlds most advanced notebook.

20

21

The complaint avers that contrary to Apples advertisements, the logic board is not durable or

22

designed to withstand the rigors of life on the go but rather is defective, and tends to fail when

23

used as intended (Compl. 20).

24

Named plaintiff Uriel Marcus, a California resident, allegedly purchased a new Apple

25

MacBook Pro computer containing a defective logic board in May 2012 that failed approximately

26

18 months later. Apple diagnosed the problem as a logic board failure, and declined to repair Mr.

27

Marcus computer or offer a refund, allegedly stating: You should have bought the warranty

28

(Compl. 11).

2

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page3 of 16

For the Northern District of California

United States District Court

Named plaintiff Benedict Verceles, a Texas resident, allegedly purchased a MacBook Pro

in July 2011 that suffered a logic board failure less than one month later. Apple repaired the logic

board under the computers warranty for free. The replacement logic board then allegedly failed

less than two years later. Apple informed Mr. Verceles that the replacement logic board was

defective and Apple declined to pay for its repair (Compl. 12).

The complaint puts forth the following ten claims for relief: (1) violations of Californias

Unfair Competition Law, Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code 17200; (2) violations of Californias Consumers

Legal Remedies Act (CLRA), Cal. Civ. Code 1750 et seq.; (3) violations of the Texas

Deceptive Trade Practices Act (DTPA); (4) fraud under Texas common law; (5) breach of

10

implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose; (6) breach of implied warranty of

11

merchantability; (7) violations of the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act (MMWA), 15 U.S.C.

12

2310(d)(1); (8) violations of the Song-Beverly Consumer Warranty Act, Cal. Civ. Code 1791 et

13

seq.; (9) money had and received; and (10) unjust enrichment.

14

ANALYSIS

15

To survive a motion to dismiss, a complaint must contain sufficient factual matter,

16

accepted as true, to state a claim for relief that is plausible on its face. Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S.

17

662, 663 (2009). While a court must take all of the factual allegations in the complaint as true,

18

it is not bound to accept as true a legal conclusion couched as a factual allegation. Id. at 678

19

(quoting Bell Atl. Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 555 (2007). This plausibility standard is not

20

a probability requirement. Ibid. Still, it asks more than a sheer possibility that a defendant has

21

acted unlawfully. Where a complaint pleads facts that are merely consistent with a defendants

22

liability, it stops short of the line between possibility and plausibility of entitlement to relief.

23

Ibid. (quoting Twombly, 500 U.S. at 557) (internal quotation marks omitted).

24

As an initial matter, this order addresses Apples reference to Deburro v. Apple Inc., No.

25

A-13-CA-784-SS, 2013 WL 5917665 (W.D. Tex. Oct. 31, 2013) (Judge Sam Sparks). Apple

26

avers that the Deburro action, which was dismissed with prejudice at the pleading stage in the

27

Western District of Texas, and was also brought by plaintiffs counsel Omar W. Rosales, was

28

factually similar to the instant action, and included many of the same claims for relief. Plaintiffs,

3

For the Northern District of California

United States District Court

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page4 of 16

however, contend that the instant action is dissimilar because Deburro involved defective USB

ports, instead of defective logic boards (Opp. 12). A review of the Deburro decision reveals that

the case also involved faulty logic boards and that plaintiffs similarly alleged that Apples

defective logic boards result[ed] in USB ports not functioning, or in the laptop itself being

rendered unusable and claimed their MacBook Pro laptops were not fit for use because the

logic boards failed five years after purchase. Id. at 1, 7. Apple does not allege that the instant

action is barred by res judicata, but simply raises the Deburro action as a background fact.

1.

Apple requests judicial notice be taken of two documents: (1) Apples One Year Limited

REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE.

10

Warranty for its October 4, 2011, to March 27, 2013, MacBook Pro computers (applicable to Mr.

11

Marcuss purchase); and (2) Apples One Year Limited Warranty for its MacBook Pro computers

12

before October 4, 2011 (applicable to Mr. Verceless purchase) (Dkt. No. 30-1, 2 ). Plaintiffs

13

complaint makes reference to Apples written warranty and plaintiff has not opposed Apples

14

request (Compl. 65, 76, 83). This order will therefore consider the documents in the context

15

of Apples motion. Branch v. Tunnell, 14 F.3d 449, 454 (9th Cir. 1994), overruled on other

16

grounds by Galbraith v. County of Santa Clara, 3017 F.3d 1119 (9th Cir. 2002). Apples request

17

for judicial notice is GRANTED.

18

2.

19

The complaint alleges that Apple violated provisions of Section 17200 of Californias

FRAUD-BASED CLAIMS FOR RELIEF.

20

Unfair Competition Law, the CLRA, the Texas DTPA, and committed common law fraud in

21

Texas. Apple avers that the heightened pleading standard of FRCP 9(b) applies to those claims

22

for relief, and that plaintiffs have failed to meet their burden. This order agrees. Plaintiffs do not

23

oppose application of FRCP 9(b) to their fraud-based claims.

24

FRCP 9(b) states that [i]n alleging fraud or mistake, a party must state with particularity

25

the circumstances constituting fraud or mistake. Malice, intent, knowledge, and other conditions

26

of a persons mind may be alleged generally. Our court of appeals has interpreted FRCP 9(b) to

27

require that a plaintiff state the who, what, when, where, and how of the misconduct charged as

28

4

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page5 of 16

well as what is false or misleading about a statement, and why it is false. Ebeid ex rel. U.S. v.

Lungwitz, 616 F.3d 993, 998 (9th Cir. 2010) (citations and quotation marks omitted).

For the Northern District of California

United States District Court

Claims brought under Section 17200 or the CLRA are subject to the heightened pleading

standards of FRCP 9(b) if the claims are grounded in fraud, meaning that the claims rely on a

unified course of fraudulent conduct. Kearns v. Ford Motor Company, 567 F.3d 1120, 1125 (9th

Cir. 2009). Plaintiffs here allege a fraudulent course of conduct, stating that Apple was aware of

the defective logic boards, misrepresented its products qualities, failed to disclose the defect to

consumers, continued to market and sell computers containing defective logic boards, and

concealed knowledge of the defect. Plaintiffs also specifically allege common law fraud (Compl.

10

3, 9498). FRCP 9(b) therefore applies to plaintiffs claims under Section 17200 and the

11

CLRA. Plaintiffs Texas common law fraud claims are additionally subject to FRCP 9(b).

12

Flaherty & Crumrine Preferred Income Fund, Inc. v. TXU Corp., 565 F.3d 200, 213 (5th Cir.

13

2009). Plaintiffs fraud-based DTPA claims alleging false, misleading, or deceptive acts or

14

practices are similarly subject to FRCP 9(b). See e.g. Frith v. Guardian Life Ins. Co. of Am., 9 F.

15

Supp. 2d 734, 742 (S.D. Tex. 1998).

16

17

A.

Section 17200.

The complaint alleges that Apple violated Section 17200 of Californias Unfair

18

Competition Law, which proscribes unfair competition including any unlawful, unfair or

19

fraudulent business act or practice . . . Specifically, plaintiffs allege that Apple violated two

20

prongs of Section 17200, the unlawful prong and the unfair prong. (Compl. 48, 50).

21

Under the unlawful prong of Section 17200, plaintiffs may borrow violations of other

22

laws for purposes of establishing Section 17200 liability. Cel-Tech Communications, Inc v. Los

23

Angeles Cellular Tel. Co., 20 Cal. 4th 163, 180, 973 P.2d 527, 539 (1999). The complaint alleges

24

that Apple committed an alleged unlawful act or practice by selling defective and non-

25

merchantable laptops, failing to use reasonable care in testing its laptops, and by continuing

26

to sell its defective laptops after learning that the logic boards would fail prematurely . . .

27

Plaintiffs aver that these alleged actions violate a list of statutes, namely: California Civil Code

28

Sections 1770(a) and 1791, et seq., California Commercial Code Sections 2313 and 2314,

5

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page6 of 16

Uniform Commercial Code Sections 2-313 and 2-315, the MMWA (15 U.S.C. 2310(d)(1)), and

other common law doctrines (Compl. 48).

3

4

Section 17200 claims. As discussed later in this order, plaintiffs fail to establish underlying

violations of the CLRA (Cal. Civ. Code 1770(a)), the Song-Beverly Consumer Warranty Act

(Cal. Civ. Code 1791), and the MMWA (15 U.S.C. 2310(d)(1)). Plaintiffs provide no other

specific facts as to Apples alleged violations of the remaining statutes. Merely naming the

statutes is insufficient. The complaint therefore does not state with the required particularity how

Apples alleged conduct was unlawful under Section 17200.

For the Northern District of California

10

United States District Court

Plaintiffs have not met the heightened pleading standards of FRCP 9(b) in alleging their

The complaint also alleges that the same conduct constituted unfair acts or practices

11

within the meaning of Section 17200. Although California courts have employed multiple

12

methods for defining unfair under Section 17200, the so-called balancing test is frequently

13

used. Under that test, the court examines the moral nature of the challenged business practice and

14

weighs the utility of the defendants conduct against the gravity of the harm to the alleged victim.

15

Pirozzi v. Apple, Inc., 966 F. Supp. 2d 909, 922 (N.D. Cal. 2013) (Judge Jon S. Tigar). Here,

16

plaintiffs merely state in conclusory fashion that Apples practices offend public policy and are

17

unethical, oppressive, unscrupulous and violate the laws stated above. The complaint does not

18

state what public policy is offended, or why Apples acts were unethical, oppressive, or

19

unscrupulous. Instead, plaintiffs baldly state that the gravity of Defendants alleged wrongful

20

conduct outweighs any purported benefits attributable to such conduct. Without more, such

21

unsupported assertions fail to meet the particularity required under FRCP 9(b).

22

Furthermore, since plaintiffs Section 17200 claim sounds in fraud, plaintiffs are required

23

to prove actual reliance on the allegedly deceptive or misleading statements. Sateriale v. R.J.

24

Reynolds Tobacco Co., 697 F.3d 777, 793 (9th Cir. 2012). The only averment stating that

25

plaintiffs relied on Apples representations appears in the complaints recitation of the elements

26

of common law fraud (Compl. 95). The complaint does not allege which of Apples

27

representations were relied upon, when they were relied upon, or by whom.

28

6

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page7 of 16

1

2

Plaintiffs have not sufficiently plead any violation of a borrowed statute under the

Section 17200. Apples motion to dismiss plaintiffs Section 17200 claim is GRANTED.

B.

For the Northern District of California

United States District Court

CLRA.

Plaintiffs allege that Apple violated three subsections of Section 1770(a) of the CLRA,

which proscribes unfair methods of competition and unfair or deceptive acts or practices in sales

to consumers. Apple avers that plaintiffs have failed to plead violations of the CLRA with the

particularity required under FRCP 9(b).

The complaint alleges that Apple violated Section 1770(a)(5) by misrepresenting that the

laptops in question have characteristics, benefits, or uses which they do not have. Plaintiffs also

10

aver that Apple violated Section 1770(a)(7) by misrepresenting that the laptops in question are

11

of a particular standard, quality, and/or grade, when they are of another. Finally, the complaint

12

alleges that Apple violated Section 1770(a)(9) by advertising the laptops in question with the

13

intent not to sell them as advertised or represented (Compl. 55(a), (b), (c)).

14

As noted, the complaint puts forth only four examples of representations or

15

advertisements allegedly made by Apple regarding the laptop computers (Compl. 2, 17, 18,

16

19):

17

18

19

20

Regarding the Macbook Pro series laptop computers, Apple makes

the following representations: State of the Art, Breakthrough,

Easy Access to Connections and Ports.

Regarding the MacBook series laptop computers, Apple makes the

following representations: The new MacBook is faster, has even

more memory and storage, and is an ideal notebook for customers

growing library of digital music, photos and movies.

21

22

Apple also boasts that its MacBook Pro is its state of the art

flagship portable designed for mobile professionals and life on

the road.

23

24

The MacBook Pro and Macbook were represented as being, The

worlds most advanced notebook.

25

None of these representations mentions the computers allegedly defective logic board. Plaintiffs

26

do not specifically allege how the statements are false or misleading. The complaint merely avers

27

that Apple has made uniform representations that its laptops are high-quality products that will

28

perform as represented and that contrary to its advertisements, Apples logic board is not

7

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page8 of 16

durable or designed to withstand the rigors of life on the go but rather is defective and tends to

fail when used as intended. (Compl. 20, 56). Plaintiffs allegations do not correspond to the

text of the four alleged Apple representations. None of those representations contains the word

durable, and the complaint provides no facts or context indicating that Apple represented its

products as durable.

For the Northern District of California

United States District Court

In their opposition, plaintiffs assert that the phrases Most Advanced Notebook Ever and

State-of-the-Art are actionable when presented within a technical presentation that includes

technical specifications (Opp. 16). In support, plaintiffs cite our court of appeals decision in

Southland Sod Farms v. Stover Seed Co., 108 F.3d 1134, 1145 (9th Cir. 1997), which stated that

10

[a] specific and measurable advertisement claim of product superiority based on product testing

11

is not puffery.

12

This order detects nothing specific or measurable about the phrases Most Advanced

13

Notebook Ever or State-of-the-Art. Those representations and the four put forth in the

14

complaint constitute non-actionable puffery. Further, the court in Deburro explicitly found the

15

first two of the representations quoted above to be generic and non-actionable. 2013 WL

16

5917665 at 4.

17

Plaintiffs also cite Sanders v. Apple, 672 F. Supp.2d 978, 988 (N.D. Cal. 2009) (Judge

18

Jeremy Fogel), which, in discussing representations regarding computer monitors, stated that

19

while in an advertising context the phrase millions of colors might be considered a vague

20

superlative, the fact that the phrase was used in the technical specifications section of Apples

21

website transforms it into an express warranty . . . Plaintiffs here contend that Apples

22

representations, if presented alongside a technical specification, would be actionable. Not so.

23

Plaintiffs complaint did not attempt to establish the context of the representations, but merely

24

provided URLs and in one instance the date of a press release. Furthermore, the phrase millions

25

of colors is facially more measurable than plaintiffs proffered representations. Plaintiffs

26

proffered misrepresentations, which do not include statements of durability, are mere puffery.

27

Plaintiffs have therefore failed to adequately plead a violation of Section 1770(a) with the

28

particularity required under FRCP 9(b).

8

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page9 of 16

1

2

plead on a fraud by omission theory. Plaintiffs point to Falk. V. General Motors Corp., 496

F.Supp.2d 1088, 1095 (N.D. Cal. 2007), to allege that Apple had a duty to disclose the logic

board defect because Apple had superior knowledge of the defect and actively concealed it. That

failure to disclose, plaintiffs aver, constitutes an unlawful omission under the CLRA.

For the Northern District of California

United States District Court

In their opposition, plaintiffs additionally allege that their CLRA claims are adequately

In response, Apple cites our court of appeals in Wilson v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 668 F.3d

1136, 1141 (9th Cir. 2012), which considered Falk in the context of an allegedly concealed design

defect under the CLRA. The court in Wilson stated California courts have generally rejected a

broad obligation to disclose, and that generally a manufacturers duty to consumers is limited to

10

its warranty obligations absent either an affirmative misrepresentation or safety issues. Ibid.

11

(citing Daugherty v. American Honda Motor Co., 144 Cal. App. 4th 824, 835 (2006)). As already

12

noted, plaintiffs have failed to plead the existence of any affirmative misrepresentations by Apple,

13

and have not alleged any safety issues. Apples motion to dismiss plaintiffs CLRA claims is

14

therefore GRANTED.

15

16

C.

Texas DTPA.

Plaintiffs allege that Apple violated multiple provision of the Texas Deceptive Trade

17

Practices Act, Tex. Bus. & Com. Code 17.46. Specifically, plaintiffs allege that Apple violated

18

Sections 17.46(b)(5), (7), (9), and (24). Apple avers that the claims fail under FRCP 9(b).

19

Plaintiffs claims under Sections 17.46(b)(5), (7), and (9) pertain to affirmative

20

representations made by Apple and they therefore fail for the same reasons as plaintiffs CLRA

21

claims. None of the proffered representations even mentions the allegedly defective logic board,

22

and all constitute non-actionable puffery. Plaintiffs complaint fails to plead Apples alleged

23

violation of Sections 17.46(b)(5), (7), and (9) with the particularity required under FRCP 9(b).

24

25

26

27

Section 17.46(b)(24) proscribes:

failing to disclose information concerning goods or services which

was known at the time of the transaction if such failure to disclose

such information was intended to induce the consumer into a

transaction into which the consumer would not have entered had

the information been disclosed;

28

9

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page10 of 16

Plaintiffs claim under Section 17.46(b)(24) would require Apple to have had knowledge of the

alleged logic board defect at the time of the computers sale. FRCP 9(b) states that knowledge

may be alleged generally.

4

5

reasons. The complaint alleges that in 2011, Apple CEO Tim Cook was told of the logic board

defect, but chose to do nothing (Compl. 3). Plaintiffs provide no supporting facts for this

alleged communication or the context. Plaintiffs also allege (Compl. 22):

8

9

For the Northern District of California

10

United States District Court

The complaint avers that Apple had knowledge of the defective logic boards for several

Apple knows about this logic board defect. Combining a

defective product design and manufacturing plants in China that

engage in human rights violations (including child labor)

Defendant Apple and CEO Timothy Cook have known about

the situation for years.

11

To the extent discernible, plaintiffs allege that the nature and existence of Apples manufacturing

12

operations in China was sufficient to impart Apple with knowledge of the alleged logic board

13

defect. This order disagrees.

14

Plaintiffs also allege that Apple had knowledge of the defect by way of customer

15

complaints posted to the Apple website. Between December 2010 and July 2012, customers

16

posted more than 365 reviews of laptop failures. The complaint excerpts 27 of these

17

anonymous reviews purportedly relating to logic board failures (Compl. 23, 24). Plaintiffs do

18

not indicate what number of those alleged 365 reviews referenced a logic board failure as

19

opposed to any other type of laptop failure. Additionally, all but four of the 27 excerpted

20

customer reviews were posted after Mr. Verceles allegedly purchased his computer in July 2011.

21

After review of the complaint, it cannot be said that Apple was plausibly imbued with knowledge

22

of the logic board defect through anonymous customer reviews posted to Apples website for

23

purposes of Section 17.46(b)(24). Cf. Berenblat v. Apple, Inc., Nos. 08-4969 JF (PVT), 09-1649

24

JF (PVT, 2010 WL 1460297 at 9 (N.D. Cal. 2013) (Judge Jeremy Fogel) (complaints posted to

25

Apples website established the fact that consumers were complaining, not that Apple had notice

26

of defect). Plaintiffs further state that the web page listing MacBook Pro Logic Board Failure

27

has been viewed more than 140,000 times. Plaintiffs do not allege who viewed this web page,

28

10

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page11 of 16

when it was viewed, or how its passive viewing put Apple on notice of the alleged logic board

defect.

3

4

notifying Apple of its alleged breach of the DTPA is insufficient to establish knowledge under

Section 17.46(b)(24). The complaint does not state when such a notice was sent to Apple, and

whether Apple received the notice prior to plaintiffs purchases. Apples motion to dismiss

plaintiffs claim under the Texas DTPA is therefore GRANTED.

For the Northern District of California

United States District Court

Finally, the alleged notification sent to Apple by plaintiffs pursuant to Section 17.505(a)

D.

Texas Common Law Fraud.

The elements of fraud in Texas are: (1) a material representation was made; (2) the

10

representation was false; (3) when the representation was made, the speaker knew it was false or

11

made it recklessly without any knowledge of the truth and as a positive assertion; (4) the speaker

12

made the representation with the intent that the other party should act upon it; (5) the party acted

13

in reliance on the representation; and (6) the party thereby suffered an injury. In re FirstMerit

14

Bank, N.A., 52 S.W.3d 749, 758 (Tex. 2001). Plaintiffs fraud claim is governed by FRCP 9(b).

15

Plaintiffs allege that Apple committed fraud because it represented that its MacBook

16

computers were functional and suitable for sale, Apple sold those computers with defective logic

17

boards, Apple knew the logic boards were defective, Apple advertised that the computers were

18

suitable for use, and plaintiffs relied on Apples statement of reliability (Compl. 95).

19

For the reasons noted, the complaint fails to plead the second element of fraud, as

20

plaintiffs have not adequately alleged misrepresentations by Apple. The four alleged

21

misrepresentations constitute non-actionable puffery and therefore cannot be adjudged false.

22

Those same representations do not even mention the allegedly defective logic boards.

23

Furthermore, and as noted supra, plaintiffs fail to plead reliance with the particularity required

24

under FRCP 9(b). This order need not consider the other elements of plaintiffs fraud claim.

25

In their opposition brief, plaintiffs assert a claim of fraud by omission, stating that the

26

claim was adequately plead under FRCP 9(b) and requires fewer alleged facts regarding time,

27

place, and specific content of an omission than claims of affirmative fraud (Opp. 27). Apple

28

11

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page12 of 16

avers that plaintiffs claim for relief was improperly raised for the first time in plaintiffs

opposition brief, and that the complaint alleged fraud based on misrepresentations, not omissions.

For the Northern District of California

United States District Court

As noted supra, plaintiffs put forth four alleged misrepresentations as a basis for this

action. Plaintiffs also specifically alleged that Apple advertised the suitability of its computers

and that plaintiffs relied on Apples statements (Compl. 95). Plaintiffs may not attempt to

change the nature of their fraud allegations in response to Apples motion. However, even if this

order were to consider plaintiffs purported claim for fraud by omission, it would still fail under

FRCP 9(b). Nondisclosure, as a type of misrepresentation in a fraud claim, must be pled with

particularity under FRCP 9(b). Kearns, 567 F.3d at 112627 (9th Cir. 2009). Plaintiffs

10

pleadings do not state the nature of the nondisclosure or omission with the particularity required

11

under FRCP 9(b). Apples motion to dismiss plaintiffs common law fraud claim is therefore

12

GRANTED.

13

3.

WARRANTY-BASED CLAIMS FOR RELIEF.

14

Plaintiffs assert claims for relief for violations of the Song-Beverly Consumer Warranty

15

Act, breach of implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose, breach of implied warranty of

16

merchantability, and violations of the MMWA.

17

18

A.

Song-Beverly Consumer Warranty Act.

Plaintiffs allege Apple violated provisions of the Song-Beverly Consumer Warranty Act,

19

California Civil Code 1791 et seq., by breaching certain implied warranties. Apple avers that the

20

Act only applies to products purchased in California, and because plaintiffs have not alleged such

21

purchases in California, plaintiffs claims fail.

22

The California Supreme Court has held that the Song-Beverly Act only applies to goods

23

purchased in California. Cummins, Inc. v. Superior Court, 36 Cal. 4th 478, 493 (2005).

24

Plaintiffs complaint does not allege in what state Mr. Marcus or Mr. Verceles purchased their

25

computers. In an effort to correct this pleading defect, plaintiffs appended sworn affidavits from

26

Mr. Marcus and Mr. Verceles to their opposition declaring the computers place of purchase

27

(Response Exh. 7). Mr. Marcus states that his computer was purchased online from Apple in

28

California, and that the computer was shipped to his home in California. Mr. Verceles states that

12

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page13 of 16

he purchased his computer in Texas. Plaintiffs complaint does not state where the purchases

were made, and the affidavits confirm that Mr. Verceles purchased his computer in Texas. Mr.

Verceles therefore has no claim under the Act.

For the Northern District of California

United States District Court

Furthermore, at oral argument, plaintiffs contended that the California Supreme Courts

decision in Aryeh v. Canon Business Solutions, Inc., 55 Cal. 4th 1185, 119192 (2013), tolled the

statute of limitations for breach of warranty claims until the defect was discovered. Plaintiffs

argue that this holding allows them to pursue their Song-Beverly claims despite the fact that their

alleged defects appeared after Apples express warranty expired. Not so. Aryeh held that the

statute of limitations for a UCL deceptive practices claim may be tolled under the discovery rule.

10

Aryeh did not extend this statute of limitations holding to breach of warranty claims. To do so

11

would be nonsensical. If a warranty period on a product did not begin to toll until the purchaser

12

discovered a defect, the warranty would be useless. A product could break twelve years after it

13

was purchased and under plaintiffs theory, the warranty time period would begin then. This is

14

not what Aryeh held and nothing in that decision saves plaintiffs in our case.

15

16

17

18

Apples motion to dismiss plaintiffs claims under the Song-Beverly Act is therefore

GRANTED.

B.

Implied Warranty of Fitness for a Particular Purpose.

Plaintiffs allege that Apple impliedly warranted that its laptops were reasonably fit for its

19

particular purpose, i.e., to withstand usual wear as a portable device . . . . without premature

20

failure of its logic board (Compl. 72). In its motion, Apple avers that plaintiffs failed to

21

adequately plead the elements of an implied warranty of fitness claim. This order agrees, and

22

plaintiffs offer no substantive opposition to Apples motion in this regard.

23

In order to state a claim for breach of implied warranty of fitness under Section 2315 of

24

the California Commercial Code, a plaintiff must allege that (1) the seller has reason to know of a

25

particular purpose for which the goods are required, and (2) that the buyer relies on the sellers

26

skill or judgment to select or furnish suitable goods. That particular purpose differs from the

27

ordinary purpose for which the goods are used in that it envisages a specific use by the buyer

28

which is peculiar to the nature of his business. Am. Suzuki Motor Corp. v. Superior Court, 37

13

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page14 of 16

Cal. App. 4th 1291, 1295 n. 2 (1995) (citations omitted). In defining the implied warranty of

fitness, Section 2.315 of the Texas Business and Commerce Code similarly requires that a seller

has reason to know any particular purpose for which the goods are required, and defines

particular purpose as differing from the ordinary purpose for which the goods are used.

5

6

than their ordinary use as a portable device. Apples motion to dismiss plaintiffs claim for

breach of implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose is therefore GRANTED.

For the Northern District of California

United States District Court

Here, plaintiffs plainly fail to allege that the computers were used for any purpose other

C.

Implied Warranty of Merchantability.

Plaintiffs allege that Apple impliedly warranted that its laptops were reasonably

10

functional for its intended use, i.e., to withstand usual wear as a portable device and to operate the

11

laptop without premature failure. Plaintiffs further aver that Apples laptops are not

12

merchantable because the logic board fails and disables the laptop, rendering the device useless

13

(Compl. 79, 80). Apple alleges that plaintiffs have inadequately plead a breach of the implied

14

warranty of merchantability.

15

The implied warranty of merchantability warrants that goods are fit for the ordinary

16

purposes for which such goods are used. Cal. Com. Code 2314(c); Tex. Bus. Com. Code

17

2.314(b)(3). The warranty does not impose a general requirement that goods precisely fulfill the

18

expectations of the buyer, but instead provides for a minimum level of quality. Am Suzuki at

19

1296 (citation omitted). A breach of the implied warranty of merchantability means the product

20

did not possess even the most basic degree of fitness for ordinary use. Mocek. v. Alfa Leisure,

21

Inc., 114 Cal. App. 4th 402, 406 (2003). A product which performs its ordinary function

22

adequately does not breach the implied warranty of merchantability merely because it does not

23

function as well as the buyer would like, or even as well as it could. General Motors Corpo. v.

24

Brewer, 966 S.W.2d 56, 57 (1998).

25

Plaintiffs have failed to adequately plead a breach of the implied warranty of

26

merchantability. Mr. Marcus alleges that his computers logic board failed 18 months after its

27

purchase. Mr. Verceles first computer allegedly suffered a logic board failure one month after

28

purchase, but was replaced by Apple for free under warranty. His second computers logic board

14

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page15 of 16

then failed less than two years later. Plaintiffs have failed to allege that Apples logic boards

were unfit for their ordinary purposes or lacked a minimal level of quality. Both plaintiffs were

able to adequately use their computers for approximately 18 months and two years, respectively.

Apples motion to dismiss plaintiffs claim for breach of the implied warranty of

merchantability is therefore GRANTED.

For the Northern District of California

United States District Court

D.

Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act.

Plaintiffs allege a violation of the Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act, 15 U.S.C. 2301, et seq.

A court applies state warranty law for claims under the MMWA. Birdsong v. Apple, Inc., 590

F.3d 955, 958 n. 2 (9th Cir. 2009). Because the complaint fails to adequately plead state law

10

implied warranty claims, plaintiffs claims under the MMWA similarly fail. Apples motion to

11

dismiss plaintiffs MMWA claim is therefore GRANTED.

12

4.

MONEY HAD AND RECEIVED & UNJUST ENRICHMENT.

13

Plaintiffs assert claims for both money had and received and unjust enrichment. Apple

14

avers that neither is a cause of action in Texas or California. Plaintiffs opposition brief does not

15

address Apples motion with regard to money had and received, and plaintiffs have not put

16

forward any authority supporting the cause of action. Plaintiffs claim for money had and

17

received is therefore conceded and Apples motion to dismiss the claim is GRANTED.

18

Plaintiffs do assert, however, that unjust enrichment is a valid cause of action under

19

California law. In California, unjust enrichment is an action in quasi-contract, which does not lie

20

when an enforceable, binding agreement exists defining the rights of the parties. Paracor

21

Finance, Inc. v. General Electric Capital Corp., 96 F.3d 1151, 1167 (9th Cir. 1996). As noted

22

supra, plaintiffs purchased computers were subject to Apples express Limited Warranty. The

23

existence of Apples express Limited Warranty therefore precludes unjust enrichment as a cause of

24

action, and Apples motion to dismiss plaintiffs claims is therefore GRANTED.

25

CONCLUSION

26

For the foregoing reasons, Apples motion to dismiss is GRANTED.

27

Plaintiffs will have until JANUARY 22, 2015 AT NOON, to file a motion, noticed on the

28

normal 35-day calendar, for leave to amend their claims. A proposed amended complaint must be

15

Case3:14-cv-03824-WHA Document45 Filed01/08/15 Page16 of 16

appended to this motion. Plaintiffs must plead their best case. The motion should clearly explain

how the amended complaint cures the deficiencies identified herein, and should include as an

exhibit a redlined or highlighted version identifying all changes. If such a motion is not filed by

the deadline, this case will be closed.

5

IT IS SO ORDERED.

6

7

Dated: January 8, 2015.

WILLIAM ALSUP

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

8

9

11

For the Northern District of California

United States District Court

10

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

16

También podría gustarte

- SC Rules Plebiscite on Lowering Voting Age to 18 InvalidDocumento2 páginasSC Rules Plebiscite on Lowering Voting Age to 18 Invalidadonaiaslarona83% (6)

- Pre-Trial Brief (Plaintiff)Documento5 páginasPre-Trial Brief (Plaintiff)Katherine EvangelistaAún no hay calificaciones

- AppleCare Class Action Proposed SettlementDocumento28 páginasAppleCare Class Action Proposed SettlementMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Sovereign Grace Ministries Inc.'s Motion To Dismiss Lawsuit Case No. 369721-VDocumento30 páginasSovereign Grace Ministries Inc.'s Motion To Dismiss Lawsuit Case No. 369721-VMandyAún no hay calificaciones

- Prosecutorial Misconduct by CullersDocumento2 páginasProsecutorial Misconduct by CullersThomas HorneAún no hay calificaciones

- 37 2016 00015560 CL en CTL Roa 1-05-09 16 CA Labor Board Judgment Digital Ear, IncDocumento15 páginas37 2016 00015560 CL en CTL Roa 1-05-09 16 CA Labor Board Judgment Digital Ear, IncdigitalearinfoAún no hay calificaciones

- Washington State vs. Comcast - Motion To DismissDocumento29 páginasWashington State vs. Comcast - Motion To DismissTodd BishopAún no hay calificaciones

- Randy Ankeney Case: Supreme Court Opening BriefDocumento41 páginasRandy Ankeney Case: Supreme Court Opening BriefMichael_Lee_RobertsAún no hay calificaciones

- Clackamas Jail LawsuitDocumento40 páginasClackamas Jail LawsuitKGW News100% (1)

- Discussion Board#1-Beckworth v. BeckworthDocumento4 páginasDiscussion Board#1-Beckworth v. BeckworthMuhammad Qasim Sajid0% (1)

- ImmerVision v. AppleDocumento5 páginasImmerVision v. AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Aire Technology v. AppleDocumento32 páginasAire Technology v. AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- TOT Power Control v. AppleDocumento28 páginasTOT Power Control v. AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- RFCyber v. AppleDocumento60 páginasRFCyber v. AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Apple Class Action LawsuitDocumento44 páginasApple Class Action LawsuitWashington ExaminerAún no hay calificaciones

- Petition for Certiorari: Denied Without Opinion Patent Case 93-1413De EverandPetition for Certiorari: Denied Without Opinion Patent Case 93-1413Aún no hay calificaciones

- California Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionDe EverandCalifornia Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionCalificación: 4 de 5 estrellas4/5 (1)

- Opposition of Motion To DismissDocumento5 páginasOpposition of Motion To DismissBonnie BoldenAún no hay calificaciones

- 24-CV-20-1788 - 24-CV-21-159 AG v. MLH 6-4-21 ORD MEM-FINALDocumento20 páginas24-CV-20-1788 - 24-CV-21-159 AG v. MLH 6-4-21 ORD MEM-FINALSally Jo SorensenAún no hay calificaciones

- Fema Community Outreach Plan TemplateDocumento20 páginasFema Community Outreach Plan TemplateHannah PayasAún no hay calificaciones

- November 2012 Ohio Board of Nursing NoticesDocumento642 páginasNovember 2012 Ohio Board of Nursing NoticesJames LindonAún no hay calificaciones

- Notice and Request For HearingDocumento1 páginaNotice and Request For HearingAnakataAún no hay calificaciones

- People of The State of California v. J.P. Morgan Chase, Chase Bank N.A., and Chase Bankcard ServicesDocumento10 páginasPeople of The State of California v. J.P. Morgan Chase, Chase Bank N.A., and Chase Bankcard ServicesNicholas M. MocciaAún no hay calificaciones

- Evidentiary Objections To Wilhelmi DeclDocumento5 páginasEvidentiary Objections To Wilhelmi DeclBernie KimmerleAún no hay calificaciones

- Mtion To Supplement The Record - Court StampDocumento21 páginasMtion To Supplement The Record - Court StampLee PedersonAún no hay calificaciones

- Appeals Court Decision HAVERHILL STEM, LLC & Another vs. LLOYD A JENNINGS & Another 2020-P-0537Documento20 páginasAppeals Court Decision HAVERHILL STEM, LLC & Another vs. LLOYD A JENNINGS & Another 2020-P-0537Grant EllisAún no hay calificaciones

- Jurisdiction RemDocumento83 páginasJurisdiction RemLlewellyn Jr ManjaresAún no hay calificaciones

- GOP Defamation LawsuitDocumento7 páginasGOP Defamation LawsuitColton LochheadAún no hay calificaciones

- NOTICE of APPEAL Supreme Court CertificationDocumento4 páginasNOTICE of APPEAL Supreme Court CertificationNeil GillespieAún no hay calificaciones

- Mansion Party TRO Petition E-FiledDocumento21 páginasMansion Party TRO Petition E-FiledKVIA ABC-7Aún no hay calificaciones

- Rhodes Motion For Judicial NoticeDocumento493 páginasRhodes Motion For Judicial Noticewolf woodAún no hay calificaciones

- Cease and Desist Letter To Lafayette Consolidated GovernmentDocumento4 páginasCease and Desist Letter To Lafayette Consolidated GovernmentBusted In AcadianaAún no hay calificaciones

- Wepay v. McDonalds - ComplaintDocumento21 páginasWepay v. McDonalds - ComplaintSarah BursteinAún no hay calificaciones

- Declaratory Judgment Action by Symantec Against RPostDocumento16 páginasDeclaratory Judgment Action by Symantec Against RPostbridges3955Aún no hay calificaciones

- All Public Officials Are Bound by This Oath 09012013 PDFDocumento2 páginasAll Public Officials Are Bound by This Oath 09012013 PDFuad812100% (1)

- United States Court of Appeals, Third Circuit, 531 F.2d 132, 3rd Cir. (1976)Documento14 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals, Third Circuit, 531 F.2d 132, 3rd Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Chrysler v. Brown, 441 U.S. 281 (1979)Documento3 páginasChrysler v. Brown, 441 U.S. 281 (1979)jpesAún no hay calificaciones

- Order On Proposed Motions in CRISPR CaseDocumento19 páginasOrder On Proposed Motions in CRISPR Casejssherkow100% (1)

- Clerk Heathcoat Obstructs Filing of Notice of Appeal, 08/03/2010Documento62 páginasClerk Heathcoat Obstructs Filing of Notice of Appeal, 08/03/2010Judicial_FraudAún no hay calificaciones

- Puente - Arizona - Et - Al - v. - Arpai RESPONSE To Motion Re MOTION For Summary Judgment County Defendants' Joint Response in Opposition To Plaintiffs' Motion For Partial Summary JudgmentDocumento36 páginasPuente - Arizona - Et - Al - v. - Arpai RESPONSE To Motion Re MOTION For Summary Judgment County Defendants' Joint Response in Opposition To Plaintiffs' Motion For Partial Summary JudgmentChelle CalderonAún no hay calificaciones

- Notice of OppositionDocumento5 páginasNotice of OppositionSimply SherrieAún no hay calificaciones

- State of Hawaii's Motion For Summary Judgment, Bridge Aina Lea v. State of Hawaii Land Use Comm'n, No. 11-00414 SOM BMK (D. Haw. Filed Dec. 31, 2015)Documento36 páginasState of Hawaii's Motion For Summary Judgment, Bridge Aina Lea v. State of Hawaii Land Use Comm'n, No. 11-00414 SOM BMK (D. Haw. Filed Dec. 31, 2015)RHTAún no hay calificaciones

- WL CountersuitDocumento22 páginasWL CountersuitSockjigAún no hay calificaciones

- Understanding antitrust laws and how they protect consumersDocumento10 páginasUnderstanding antitrust laws and how they protect consumersselozok1Aún no hay calificaciones

- 10-03-23 Richard Fine: Requesting Ronald George, Chair of The Judicial Council To Take Corrective Actions in Re: Conduct of Attorney Kevin MccormickDocumento16 páginas10-03-23 Richard Fine: Requesting Ronald George, Chair of The Judicial Council To Take Corrective Actions in Re: Conduct of Attorney Kevin MccormickHuman Rights Alert - NGO (RA)100% (1)

- Feibush - Motion To DismissDocumento15 páginasFeibush - Motion To DismissPhiladelphiaMagazineAún no hay calificaciones

- Caner vs. Autry Et Al. Motion To Sever Case Into TwoDocumento12 páginasCaner vs. Autry Et Al. Motion To Sever Case Into TwoJason SmathersAún no hay calificaciones

- Oregon v. Barry Joe Stull Motions January 22, 2020 FinalDocumento60 páginasOregon v. Barry Joe Stull Motions January 22, 2020 Finalmary engAún no hay calificaciones

- Hawaii Office of Information Practices Opinion No. 04-02 Re: Office of Disciplinary Counsel and Disciplinary BoardDocumento20 páginasHawaii Office of Information Practices Opinion No. 04-02 Re: Office of Disciplinary Counsel and Disciplinary BoardIan LindAún no hay calificaciones

- Penny K. Manzi and JERRY S, Manzi,: Northern District OF IllinoisDocumento7 páginasPenny K. Manzi and JERRY S, Manzi,: Northern District OF IllinoisMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Notice of Motion and Motion To Dismiss and (2) Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of MotionDocumento32 páginasNotice of Motion and Motion To Dismiss and (2) Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of Motion3inge23Aún no hay calificaciones

- US Department of Justice Antitrust Case Brief - 00739-200243Documento51 páginasUS Department of Justice Antitrust Case Brief - 00739-200243legalmattersAún no hay calificaciones

- Man DamusDocumento10 páginasMan DamusAnonymous Qn8AvWvxAún no hay calificaciones

- Mayfield 447 Notice of AppealDocumento3 páginasMayfield 447 Notice of Appealthe kingfishAún no hay calificaciones

- Jameswoods Doe OppoDocumento55 páginasJameswoods Doe OppoEriq GardnerAún no hay calificaciones

- Declaration in Support of Motion To Set Aside Conviction - OREGONDocumento1 páginaDeclaration in Support of Motion To Set Aside Conviction - OREGONLaw Works LLC100% (1)

- Motion For Summary Judgment, LegalForce RAPC v. Demassa (UPL, California, Before USPTO)Documento29 páginasMotion For Summary Judgment, LegalForce RAPC v. Demassa (UPL, California, Before USPTO)Raj Abhyanker100% (1)

- Identity Security V AppleDocumento15 páginasIdentity Security V AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Judy v. Obama - Discretionary Application For Review - Georgia Supreme CourtDocumento67 páginasJudy v. Obama - Discretionary Application For Review - Georgia Supreme CourtCody Robert JudyAún no hay calificaciones

- Motion For Summons of Grand JuryDocumento14 páginasMotion For Summons of Grand JuryJeff Maehr100% (2)

- Eyaktek Opposition To MotionDocumento19 páginasEyaktek Opposition To Motionndc_exposedAún no hay calificaciones

- Court of Chancery of The State of DelawareDocumento13 páginasCourt of Chancery of The State of DelawareNate Tobik100% (1)

- 020 - Appellate BriefDocumento6 páginas020 - Appellate BriefDarren NeeseAún no hay calificaciones

- 1-13-3555 Foreclosure Service of Process UpheldDocumento7 páginas1-13-3555 Foreclosure Service of Process Upheldsbhasin1100% (1)

- Appellate Brief Cover PT IDocumento14 páginasAppellate Brief Cover PT IMARSHA MAINESAún no hay calificaciones

- Lighting the Way: Federal Courts, Civil Rights, and Public PolicyDe EverandLighting the Way: Federal Courts, Civil Rights, and Public PolicyAún no hay calificaciones

- Lepesant v. AppleDocumento24 páginasLepesant v. AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- KTI v. AppleDocumento13 páginasKTI v. AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Charming Beats v. AppleDocumento16 páginasCharming Beats v. AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Preliminary Approval of Settlement in Cameron v. AppleDocumento64 páginasPreliminary Approval of Settlement in Cameron v. AppleMacRumorsAún no hay calificaciones

- Jawbone Innovations v. AppleDocumento58 páginasJawbone Innovations v. AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Apple's Appeal in Epic Games v. Apple LawsuitDocumento24 páginasApple's Appeal in Epic Games v. Apple LawsuitMacRumorsAún no hay calificaciones

- Order Denying Apple's Motion To Stay Injunction in Epic v. AppleDocumento4 páginasOrder Denying Apple's Motion To Stay Injunction in Epic v. AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Black v. SnapDocumento24 páginasBlack v. SnapMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Apple v. Qualcomm PTAB AppealDocumento22 páginasApple v. Qualcomm PTAB AppealMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Epic v. Apple - Apple's AppealDocumento14 páginasEpic v. Apple - Apple's AppealMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Parus Holdings v. AppleDocumento33 páginasParus Holdings v. AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Smart Space v. AppleDocumento11 páginasSmart Space v. AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Apple v. Lancaster Motion To StayDocumento12 páginasApple v. Lancaster Motion To StayMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Primary Productions v. AppleDocumento66 páginasPrimary Productions v. AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Ericsson v. AppleDocumento19 páginasEricsson v. AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Universal Secure Registry v. Apple - CAFC JudgmentDocumento27 páginasUniversal Secure Registry v. Apple - CAFC JudgmentMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Cameron, Et Al v. Apple - Proposed SettlementDocumento37 páginasCameron, Et Al v. Apple - Proposed SettlementMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Class Action Complaint Against Apple Over M1 MacBook Display IssuesDocumento39 páginasClass Action Complaint Against Apple Over M1 MacBook Display IssuesMacRumorsAún no hay calificaciones

- Apple v. TraxcellDocumento12 páginasApple v. TraxcellMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- CAFC Ruling On OmniSci V AppleDocumento32 páginasCAFC Ruling On OmniSci V AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Altpass V AppleDocumento17 páginasAltpass V AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Xennial V AppleDocumento28 páginasXennial V AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Apple V VoIP-Pal DJ ComplaintDocumento22 páginasApple V VoIP-Pal DJ ComplaintMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- Xennial V AppleDocumento28 páginasXennial V AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- XR Communications:Vivato v. AppleDocumento20 páginasXR Communications:Vivato v. AppleMikey CampbellAún no hay calificaciones

- United States v. Scott, 4th Cir. (2009)Documento5 páginasUnited States v. Scott, 4th Cir. (2009)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Lukban V Optimum Development Bank (Mortgage-Rghts and Obligation)Documento2 páginasLukban V Optimum Development Bank (Mortgage-Rghts and Obligation)Robert RosalesAún no hay calificaciones

- ID990ADocumento8 páginasID990AW4NRAún no hay calificaciones

- Natural Law and Its Impact On The Indian Constitution: Submitted By: Gaurav Gandas To: Proff. Subhradipta SarkarDocumento9 páginasNatural Law and Its Impact On The Indian Constitution: Submitted By: Gaurav Gandas To: Proff. Subhradipta SarkarGauravAún no hay calificaciones

- People V BalmoresDocumento2 páginasPeople V BalmoresNico IanAún no hay calificaciones

- Principles of Information Security Laws and EthicsDocumento44 páginasPrinciples of Information Security Laws and EthicsAntonyAún no hay calificaciones

- JurisprudenceDocumento2 páginasJurisprudenceDelmer RiparipAún no hay calificaciones

- Framework Safety Case Assessment Draft 10032015Documento2 páginasFramework Safety Case Assessment Draft 10032015JohnAún no hay calificaciones

- Bpi V Cir DigestDocumento3 páginasBpi V Cir DigestkathrynmaydevezaAún no hay calificaciones

- Order Granting Sale of PropertyDocumento2 páginasOrder Granting Sale of PropertyJanet and JamesAún no hay calificaciones

- 1 Iloilo Jar Corp. v. Comglasco Corp Aguila GlassDocumento7 páginas1 Iloilo Jar Corp. v. Comglasco Corp Aguila GlassFrancis LeoAún no hay calificaciones

- ACAAC Vs AZCUNA CASE DIGESTDocumento2 páginasACAAC Vs AZCUNA CASE DIGESTJohn SolivenAún no hay calificaciones

- 5abella v. GonzagaDocumento4 páginas5abella v. GonzagaAna BelleAún no hay calificaciones

- SHB's Answer To Nevin Shapiro ComplaintDocumento39 páginasSHB's Answer To Nevin Shapiro ComplaintsouthfllawyersAún no hay calificaciones

- Commemorative Stamp DisputeDocumento3 páginasCommemorative Stamp DisputeJon SantiagoAún no hay calificaciones

- Digested CasesDocumento147 páginasDigested CasesGrigori QuinonesAún no hay calificaciones

- 5 Nature and Effect of Obligations 3Documento5 páginas5 Nature and Effect of Obligations 3keuliseutel chaAún no hay calificaciones

- Corpo Digets 1Documento11 páginasCorpo Digets 1AmberChan100% (1)

- 6 Marital Discrimination Full CaseDocumento21 páginas6 Marital Discrimination Full CasedaryllAún no hay calificaciones

- (PDF) Trial of Warrant Cases - CompressDocumento10 páginas(PDF) Trial of Warrant Cases - CompressgunnuAún no hay calificaciones

- Case No. 9 JORGE TAER v. THE HON. COURT OF APPEALSDocumento2 páginasCase No. 9 JORGE TAER v. THE HON. COURT OF APPEALSCarmel Grace KiwasAún no hay calificaciones

- 003 Daguman Sungachan V CADocumento4 páginas003 Daguman Sungachan V CADaniel Danjur DagumanAún no hay calificaciones

- In Re Hilda Soltero Harrington, Debtor. Estancias La Ponderosa Development Corporation v. Hilda Soltero Harrington and Rafael Durand Manzanal, 992 F.2d 3, 1st Cir. (1993)Documento4 páginasIn Re Hilda Soltero Harrington, Debtor. Estancias La Ponderosa Development Corporation v. Hilda Soltero Harrington and Rafael Durand Manzanal, 992 F.2d 3, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsAún no hay calificaciones

- Equity in LawDocumento13 páginasEquity in LawLautechPredegreeAún no hay calificaciones

- Latest Judgements On Sections 9, 11 of Trademark Act, 1999Documento5 páginasLatest Judgements On Sections 9, 11 of Trademark Act, 1999jayesh kimar singhAún no hay calificaciones

- Social Media Addiction Reduction Technology ActDocumento14 páginasSocial Media Addiction Reduction Technology ActMichael ZhangAún no hay calificaciones

- Liability ExplainedDocumento34 páginasLiability ExplainedAnonymous qFWInco8cAún no hay calificaciones

- Types of Criminal Trials: Warrant TrailDocumento4 páginasTypes of Criminal Trials: Warrant TrailAAKANKSHA BHATIAAún no hay calificaciones